(1999, with updates)

It’s over. The author can do no more. Proof-reading (if any) has

been completed, and the book is at the printer’s. Time is on hand

for qualms to creep in. Have loose ends been left unresolved or

blunders undetected? Has it been worth the effort (if any) to add

yet another chess book to the tens of thousands already clogging

up shelves and bibliographies? And then the tome comes out. The

reviews soon begin to appear – suspiciously soon in one or two

cases. Some wholesome, or fulsome, praise here; some temperate, or

tempestuous, criticism there. Much direct lifting from the preface

or back-cover blurb (i.e. Chess Life’s vacant treatment of

new literature) and a few brief mentions exhibiting no discernible

sign that the opus was ever opened. Or, the most

ignominious fate, no reaction at all; many chess books are

consigned to the excess baggage hold of the Caissa Express, bound

for instant oblivion. As the reviewers dispense their judgments

(if any), the author faces another decision: should he make a

public response? Ought he to take the rough with the smooth, even

if the rough includes serious misinformation arising from

ignorance, bias or spite?

In March 1999 our book Kings, Commoners and Knaves (KCK) was published by Russell Enterprises, Inc. At least it was not ignored. Indeed, it is doubtful whether any chess book of the 1990s has been accorded so much space in various prominent chess magazines. Of itself that ‘distinction’ says nothing about the quality of either the book or the reviews, but at least it makes KCK a useful case-study regarding ‘literary criticism’. The present review of the reviewers covers three journals, the BCM, New in Chess and Inside Chess. All three gave praise to KCK, but there will be no attempt here to smuggle in commendatory remarks from these or other sources. The reviewers will be faced on the negative ground of their own choosing, where they endeavoured to draw blood or, at least, to turn the tables on the author.

The preface explains KCK’s dual aim: to present new material which is true and to correct old material which is not. It is primarily a work (452 pages) about chess lore, and the ‘new material’ accounts for some 90% of the contents, with such items as an eight-page historical feature on copyrighting game-scores. Nonetheless, most reviewers elected to home in on the 10% of ‘controversial’ sections, e.g. the Gaffes chapter and some of the book reviews, and in so doing they revealed little about KCK but much about themselves.

The BCM is a periodical whose falsehood and subterfuge we have often censured. The April 1999 issue carried a review by somebody named Tim Wall which had a nasty sting in its tail. Hopeful of engineering some kind of chess Watergate against us, Wall wrote: ‘However, for all his excellent research, stylish put-downs and corrections, occasionally Winter himself commits the sin of omission.’ The ‘occasionally’ amounted to one case: a lengthy exposé of how, applying double standards, we had ignored Kenneth Neat’s 1997 criticisms of the quality of Russian translations by Hanon Russell and had even ‘defended Hanon Russell, who is – coincidentally – the publisher of Winter’s work …’

A ‘sin of omission’ can easily be imputed to any writer of any book, but in next to no time the charge was being chewed over on the Internet, under the naive, unflattering assumption that, if the BCM had printed it, it must be true. In reality, it was false, through and through. It was loosely based on a scrap of gossip given to Wall by Neat which was itself based on the latter’s faulty recollection of his private correspondence with us which, in any event, was from the 1980s. We wrote, as did Neat, to correct the BCM’s record (though what appeared under Neat’s name was still wrong). In short, a venomous soufflé had been whipped up out of nothing, and once it collapsed the BCM was in no mood to apologize. Far from withdrawing the untruth altogether, it went to great lengths on its website to touch up the review in an unavailing bid to salvage something – anything – from the original smear.

Still determined to keep veracity at arm’s length, the BCM tried again in its May issue, this time publishing (under the done-to-death heading ‘Winter of Discontent’) a three-and-a-half-page thing by Kenneth Whyld which we have described elsewhere (New in Chess, 4/1999, pages 97-98) as the silliest and most inaccurate review that a book of ours has received. He rambled on, tying himself up in knots, and even made a stab (though not much of one) at discreetly defending Raymond Keene on one matter. Most memorably, he suggested that we were guilty of ‘sloppy pedantry’ for – horror of horrors – preferring the spelling ‘Janowsky’ to ‘Janowski’. Unfortunately for Whyld, the master spelt his name both ways. Even more unfortunately for him, ‘Janowsky’ was the spelling used by Whyld himself on, for example, page 11 and page 12 of his book Chess The Records.

Whyld’s use of the phrase ‘sloppy pedantry’ was an ill-advised attempt to be clever, oblique retaliation for our having described his friend Bernard Cafferty as a ‘sloppy pedant’ on page 299 of KCK. The episode qualified Whyld for co-membership of the club. But then in the August BCM Cafferty himself chimed in, rapping his chalk on the blackboard to proclaim that ‘Janowski’ was the only permissible spelling. He ventured no response to the Chess The Records matter or, even, to any of the criticisms made of the BCM and him. This is a leitmotif: such writers ignore the (unanswerable) facts and pin their hopes on a water-muddying counter-attack. Are those really the ‘standards’ that the BCM wishes to uphold?

More than three pages were also accorded to KCK in the 3/1999 New in Chess, where Hans Ree produced one of those reviews that welcome a book whilst hammering away at it. Once again Ree performed his tight-rope act (not so much death-defying as logic-defying) of castigating Raymond Keene (calling him a writer who had decided that ‘he could not afford to squander his time on trifles like truth and style’) yet simultaneously suggesting, without any specifics, that our strictures on Keene were unfair. With a 452-page book on chess lore in his hands, Ree focussed on the 10% of ‘controversial’ material. It seemed a virtuoso performance of weary cynicism, but, to adapt an old Clive James quip, Ree is good at being wearily cynical for the same reason that midgets are good at being short. There is much in the chess world to be cynical about but, for all his writing talent, Ree’s seen-it-all-before, can’t-change-anything approach precludes him from making any significant contribution to ridding chess literature of imprecision and dishonesty. He is capable of frothing when the mood takes him, but otherwise no amount of facts about serious wrongdoing will shake his leaden indifference. This supine attitude is reminiscent of a character in Molière’s Le Misanthrope, Philinte, who declares: ‘My mind is no more offended by the sight of a dishonest, unjust and greedy man than by vultures hungry for carnage, monkeys playing mean tricks and raging wolves.’

When Ree does take a stand, it is often a peremptory one on the wrong side of the fence. Informed observers are nowadays at a loss to say anything good about the journalism of Larry Evans, who, over the past 15 years or so, has proved himself head and shoulders below normal chess writers and columnists. But seeing the negative comments concerning Evans on pages 267-268 of KCK, Ree, ever the iconoclast, decided to bestow praise upon him, though he conspicuously avoided any mention of the subject about which Evans had been taken to task.

Here, then, is the case recorded by KCK and swept under the carpet by Ree. In Chess Life Evans awarded a ‘Best Question’ prize to two readers who had attributed a Troitzky endgame study to Capablanca even though in a previous Evans column another reader had pointed out that it was Troitzky’s composition. Evans also wrongly congratulated his prize-winners on being the first with the right solution to the composition. Apprised of the truth, he refused to correct the record, on the grounds that it was unimportant whether the study was attributed to Troitzky or Capablanca. (See pages 267-268 of KCK.) A more recent example is related on pages 97-98 of the 6/1999 New in Chess (chapter and verse on how a 1998 book by Evans had five errors on a single page, even though that page contained merely a diagram and less than ten lines of text). Are those really the ‘standards’ that Ree wishes to uphold?

Both magazines discussed so far also larded their reviews with (inexact) personal references to us, but the third review adopted an ostensibly loftier approach. In the 6/1999 issue of Inside Chess John Watson devoted space aplenty to various general, or even philosophical, points, although the one he made at the greatest length is the most readily accepted, however regrettably. Yes, there are many chessplayers devoid of interest in chess history, and KCK is not for them. We may go further still, conceding that even those attached to the game’s heritage may find KCK, at least in parts, too specialized. The book provides material intended to be fresh even for readers who are well versed in history. To quote from page 5 of John Nunn’s Chess Puzzle Book, ‘in some quarters a recipe for a puzzle book seems to be to take a few positions from one puzzle book, a few from another, a pinch from a third and whisk them all together’. Such vacuous copying is done by chess writers of many kinds, and the key to breaking out of this vicious circle is research, allowing more and more neglected material to trickle into mainstream works. It might never be guessed from some of the reviews, but KCK’s chief goal has been to help in that process.

Presenting ‘unknown’ material may be trickier than it sounds, particularly in terms of judging its value and public interest. It is worthwhile to point out that Klaus Junge’s father, Otto, was an accomplished chessplayer, yet not all readers will know many games by Klaus Junge himself. Although Watson’s review included various general observations about historical research, his own interest in either Junge Senior or Junge Junior is unclear. He described as a ‘typical overstatement’ the claim in KCK that there is rampant historical ignorance of the openings, yet his own output evinces little enthusiasm for history, and virtually no use of primary sources. Why is that? Because he consulted them and found them worthless? Because he was unable to consult them? Because he was unaware of them? Or because he had no appetite for finding them?

Watson waved aside the idea of a research association, because it would not conform to practice in the United States and there are few people interested in chess history. Even if both these dubious premises were true, it would remain unclear why they would invalidate the need for a system allowing forgotten material by great masters of the past to be resurrected and preventing duplication of effort if two writers were, unbeknown to each other, working on similar projects. Furthermore, Watson disagreed with (and called eccentric) KCK’s suggestion that even basic archival and statistical information on chess is sparse, but can he point to a comprehensive and reliable listing of individual chess matches played over the centuries? That should surely be a cornerstone of the public record, yet it does not exist. As regards the raw data of game-scores, Watson rightly noted that there is available ‘an impressive collection of almost every important game of modern chess’, but he then concluded, ‘For this reason alone, chess history offers its fans more riches than any other sport’. Some of Watson’s words have been italicized here, to highlight an apparent contradiction. Those million-game databases, of unknown authorship and origin, are notoriously unfactual and incomplete with respect to all but recent chess events.

Concerning the book review section of KCK, Watson seemed to forget that it was written from the standpoint of an historian; it is for others to provide a detailed assessment of, for example, Karpov’s annotations. He even suggested that we have no real interest in chess play, and helped his case along by omitting to mention that the 452-page book on chess lore includes over 300 games and positions. It is the reviewers who have disregarded chess play, which is an unpromising field for knockabout and misrepresentation.

Many writers have referred to Hugh Myers as an ‘openings expert’, but our doing so (on page 373 of KCK) provoked a reprimand from Watson. It is worth pondering why. In that passage we were pointing out a clear-cut lie by Eric Schiller, who is an ‘enemy’ of Myers. Watson naturally had no hope of defending Schiller (a co-author of his) over the proven instance of mendacity, so his only way of lending a hand was to make a few general noises on Schiller’s behalf and at Myers’ expense. Elsewhere in his review Watson labelled Schiller one of our ‘favorite targets’, but there too he steered well clear of the underlying facts, i.e. the hundreds of gross errors that Schiller has perpetrated in the countless books that belch out under his name without a whiff of midnight oil or, even, a minimal degree of care. Are those really the ‘standards’ that Watson wishes to uphold?

In the circumstances, it was unwise for Watson’s review to raise the subject of objectivity and of taking sides (as if the two were incompatible). There is a huge difference between applying a code of ethics founded on a commitment to accuracy and truth (whereby the Schillers of this world must, in all objectivity, be lambasted) and being determined at all costs to defend the indefensible, however vaguely or covertly. Watson perceived an anti-Kasparov bias in our writings, and certainly KCK has some severe things to say about him. But where is Watson’s rebuttal of any one of them? He evidently likes the cut of Kasparov’s jib, and has no inclination to discuss uncomfortable truths. Then again, he accused us of a ‘fawning’ attitude to Fischer, but such blanket charges are as easy to trot out as purported ‘sins of omission’. Suffice it to say that Watson’s view is not shared by Fischer himself; in two 1999 radio interviews he virulently denounced comments we had made about him in a number of magazines.

How easy it is to be a book reviewer, yet how difficult to be a good one. If a common thread has been identified here, it is that shameful critics follow their own personal or political agenda and objectives, rather than having a set of standards and principles applicable, and applied, to one and all. As it happens, the reviewers of KCK have pointed out no factual errors, but they have sought to gnaw away at the book’s credibility through recourse to, at best, mirrors and smoke-screens, either to blacken us (nothing new there) or to erect a spurious, proxy defence for some sad case or lost cause with whom they are acquainted. Of course, if those criticized by KCK were to defend themselves they would have to address head-on the actual issues and to admit error, an unbearable prospect for them. And so it is that the response to KCK from Messrs Evans, Keene, Schiller, etc. has been radio silence. Over and out.

Inside Chess on-line, 1999

See also the fine article is ‘Ex Acton ad Astra’ on pages 18-33 of the Spring 2007 issue of Kingpin.

Regarding the Janowsky/Janowski matter, a letter from us in the July 2000 CHESS is given in full in Janowsky Jottings. That feature article also contains this observation by us:

In the August 2000 BCM Bernard Cafferty wrote an article about Hoffer which referred, on page 416, to his ‘pernicious practice’ of writing ‘Janowsky’.

Our dictionary defines ‘pernicious’ as meaning ‘wicked or malicious; causing grave harm, deadly’.

See too the second footnote on page 305 of A Chess Omnibus.

For examples of the low quality of the BCM in the late 1980s, see C.N. 1926 in Rebuttals.

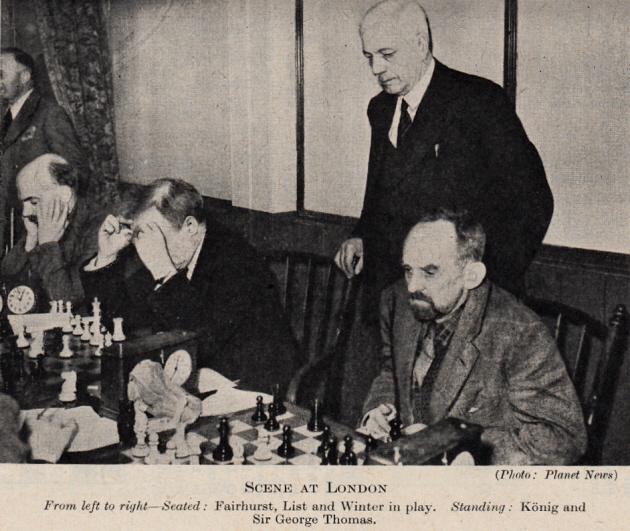

Purely by way of example, we examine here one particular untruth by K. Whyld in his review of Kings, Commoners and Knaves in the May 1999 BCM, a piece which was accompanied (on page 271) by a photograph with this caption:

‘William Winter – did Edward Winter perhaps confuse his namesake with Yates?’

The photograph was there to illustrate, and reinforce, the following attack by K. Whyld on a KCK item:

‘On page 181 he [E.W.] notes that B.H. Wood wrote “Yates died a sloven, a drunkard, in pathetic circumstances” and Winter adds “A mix-up with William Winter?” Tremendous. Two slurs for the price of one, and a bloody nose for Wood, who at least knew what he was talking about.’

Whyld then added with a further sneer: ‘They’re all dead anyway, so let’s publish.’

Let us return to the facts. On page 59 of J. Giżycki’s A History of Chess B.H. Wood wrote, ‘Yates died a sloven, a drunkard, in pathetic circumstances’. A C.N. item from 1987 which was reproduced on page 181 of KCK quoted those words of Wood’s, and we added a five-word comment of our own: ‘A mix-up with William Winter?’ The reason for this query is self-evident: the lack of such claims about Yates, coupled with the abundance of them (strongly and openly expressed) concerning William Winter. For example, the obituary in CHESS, Wood’s own magazine (24 December 1955 issue, page 101), stated that although W.W. was occasionally well-groomed he ‘might turn up at a chess match or a meeting in a state of almost indescribable filth – clothing and person alike’. Another figure well acquainted with W.W. was Harry Golombek, who wrote on page 343 of his 1977 Encyclopedia that away from the board W.W. was ‘more often than not, drunk’.

Moreover, a reader of CHESS, J.Y. Bell, discussed both F.D. Yates and W. Winter on page 212 of the 20 April 1963 issue:

‘Yates, who seems to me to have been at least as hard up as Winter, managed to present a decent appearance in public.’

To this, the Editor (i.e. B.H. Wood, the man ‘who at least knew what he was talking about’) added immediately afterwards:

‘Yes, Winter often presented a most filthy and disreputable appearance.’

That is the public record. We have not originated a single slur, let alone two. We have not given B.H. Wood ‘a bloody nose’. We merely asked a legitimate five-word question about the possibility of a mix-up over W. Winter and F.D. Yates. Remarkably, though characteristically, Whyld twisted that question into a ‘claim that Wood was wrong’.

After giving the above text in A Chess Omnibus, we added this footnote on page 308:

Another straightforward example of K. Whyld’s propensity for distortion and untruth is his assertion (Kingpin, Summer 1997, page 61) that on page 264 of Chess Explorations we ‘savaged’ Irving Chernev over a Lasker/Capablanca matter. The public record is 100% clear there too. As regards Whyld’s conduct regarding F.M. Edge (see pages 245-260 of A Chess Omnibus), at the Chess Café on 1 August 2000 we quoted a number of Frank Skoff’s apposite observations about Whyld, from a communication to C.N. dated 17 November 1989. Among the milder ones were: ‘He thinks calling people names (including myself) somehow is proof by itself’ and ‘It is astonishing how little value K.W. places on truth: He prefers its suppression at any cost. Why?’

We add the following exchanges in C.N. 1438 (after our five-word comment in C.N. 1422, ‘A mix-up with William Winter?’):

From K. Whyld:

‘I believe you are wrong in thinking there has been a mix-up. Winter died of tuberculosis in London University Hospital. Yates died from a gas leak. Both were drinkers, and both casual, at least, in their appearance. I should make it clear that I never met Yates, and speak of him by hearsay only.’

Apart from B.H. Wood’s quoted paragraph, we have never see any suggestion in print that Yates was ‘a sloven, a drunkard’, whereas these epithets have frequently been applied to William Winter.

There the matter stood until, some 11 years later, Kenneth Whyld attacked us in the BCM, as quoted above.

William Winter (see C.N. 8743)

In Edge, Morphy and Staunton we commented regarding K. Whyld:

At his best, he was one of the best; at his worst, he was one of the worst.

From the same feature article:

On 30 January 2004 Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) wrote to us:

‘As an aside on the Edge letters, I know that in one of your Chess Notes Whyld was quoted as calling Edge an outright liar for his comments on Staunton. My considered view is that at least Whyld, and possibly Hooper too, very deliberately started the Morphy homosexual rumor to besmirch Morphy. If you read all of Edge’s letters, I think you, or anyone else, would have to agree that there is no suggestion that they had any kind of homosexual relationship. That doesn’t prove that Morphy was not a homosexual, but why even ever bring it up unless there exists some evidence to support such a theory? Despite all the hoohaw about how great a student of the game’s history Whyld was, I still think he was extremely devious and I greatly distrust his judgments on many matters having to do with chess.

He often ill-concealed his bias.’

And on 1 February 2004:

‘Whyld repeatedly, in my experience, sought refuge in evasion and distortion when called upon to prove some of his assertions.’

An earlier comment by Dr Brandreth was in an e-mail message to us dated 3 August 2000:

‘I have never fully understood Whyld. With me he often just evades an issue or question. I suppose I am to be able to figure out what such non-responses mean, but I find that frustrating and inadequate.’

Dr Brandreth was the publisher of a book which K. Whyld edited: Reflections by David Hooper (Yorklyn, 2000).

Our article ‘Over and Out’ referred to ‘a clear-cut lie’ by Eric Schiller and to his ‘mendacity’. The ink was hardly dry before we had occasion to note more of the same, in the form of a grotesque attack on us at his Chesscity website which was flatly untrue, not to say libellous.

As is well known, Lasker and Tarrasch played two matches, in 1908 and 1916. The first of these was for the world championship, but the second (six games only) was not. Even so, some authors have erroneously indicated that the 1916 encounter was a world title match, two examples being Karpov in Miniatures from the World Champions (Batsford, 1985, pages 43-44) and Koltanowski in With the Chess Masters (Falcon Publishers, 1972, page 48).

Koltanowski wrote: ‘Twice Tarrasch mounted a campaign to take the world title from Lasker – and twice Lasker beat him badly.’

We quoted this in the September-October 1986 issue of C.N. and simply added a five-word rhetorical question, ‘When was the second time?’ The item was included on page 160 of our 1996 book Chess Explorations.

A straightforward matter, it might be thought, but now enter Eric Schiller. In late 1999 he posted on his website the following monstrosity:

‘Young Mr Winter gives as an “example of general carelessness” that Koltanowski makes the absurd statement that Tarrasch played two matches with Lasker, as only one was played. Anyone who has followed the careers of these great players knows that there were, of course, two matches. The second match does contain some rather poor play by Tarrasch, who got clobbered, but nevertheless it was a real match. The games are presented below. In his 90s Kolty may slip up from time to time. But the insult by the impudent young chess historian is without foundation. In any case, Kolty’s witty prose and wealth of anecdotes are far more valuable than some whining lad who can’t even get the facts right.’

On another page on the same site Schiller wrote, under the heading ‘Chess Explorations and Exploitations’:

‘So when Young Salieri (not his real name, but many will recognize the moniker) claimed that he knows more about the early days of the century, when George was actually playing and eye-witnessing events, it behooved us to check the facts. The question is simple: did Lasker play one match against Tarrasch (as claimed by Young Salieri), or two, as Kolty stated. Click here for the answer.’

In short, although we had been referring to the status of the 1916 match, i.e. the (indisputable) fact that it was not for the world title, Schiller falsely and aggressively proclaimed that we were unaware of the very existence of the match.

On 14 December 1999 we sent an e-mail message to the Chesscity site asking for a retraction and apology. To quote just one paragraph from our message:

‘To claim that I am unaware of the 1916 match is absurd, if only because on page 214 of my book [Chess Explorations] I specifically referred to it. Or again, the book that I edited for Pergamon Press, World Chess Champions, included some discussion of the 1916 match, together with the annotated score of one of the games.’

Apprised of the truth, Schiller had no intention of apologizing. On 18 December he wrote to us:

‘Nio [sic] apology necessary, you are guilty of an unwarrented [sic] attack on Koltanowski. I will defend him against your garbage.’

The same day he rewrote bits of his website, maintaining the untruth that we had claimed there had been only one Lasker v Tarrasch match, intensifying his personal attack on us and introducing a fresh charge, equally groundless: now, he added, we were also guilty of ‘sloppiness, poor editing’. To be accused of that by Schiller, of all people, is priceless.

It may be recalled that our ‘Over and Out’ article mentioned that Schiller’s books contain ‘hundreds of gross errors’, and we have often quoted chapter and verse. See, for example, the 1999 Kingpin, in which we cited a selection of nearly 40 such instances from three books published by Schiller in 1999 alone. In our book Kings, Commoners and Knaves we pointed out dozens of historical and other blunders in his book World Champion Combinations (in which, for example, the chapter on Capablanca has six games and four positions, with obvious factual gaffes in every single one of them).

Our ‘Over and Out’ article also commented on how some writers who are criticized ‘ignore the (unanswerable) facts and pin their hopes on a water-muddying counter-attack’, and that is precisely what Schiller has been doing in the present case. He has brushed aside the inconvenient matter of his hundreds of gross errors, trying instead to retaliate via another issue of his own choice, Lasker v Tarrasch. But what do we find? His attempted revenge is based on a distortion of the facts which is brazen even by his own dire standards. And when it blows up in his face, he refuses to correct the record properly or apologize, preferring to launch fresh attacks, also false. Despicable? Of course. Surprising? Not at all. It is vintage Eric Schiller.

The above is reproduced from pages 304-308 of A Chess Omnibus.

To oblige Hans Ree, we offer a few words on the first matter raised by him in the 3/1999 New in Chess (pages 92-93). The reason why, nearly a decade ago, we broke off contact with Mr K. Whyld was that so much of what we wrote to him was unpleasantly misinterpreted, distorted or otherwise mangled. We add here a copper-bottomed guarantee that Mr Whyld’s account of the subsequent visitor episode is false. The same applies to much of what he wrote on pages 270-273 of the May 1999 BCM, the silliest and most inaccurate review that a book of ours has ever received.

Recent issues of the BCM have contained other misinformation about us, without, of course, any vestige of an apology so far. However, the June issue announces the appointment of a new Editor, John Saunders. We wish him well in re-establishing the BCM’s former reputation for accuracy, fairness and decency.

(2288)

In 1991 Kenneth Whyld sent a woman to our home with the sole express purpose of eliciting personal information about us. Six years later (Kingpin, Summer 1997, page 61) he wrote an overblown and inaccurate account of the visit, and in an interview/article on pages 33-38 of the November 1998 CHESS he added, in an attempt to justify the intrusion, a further untruth, i.e. a claim that the woman was there because she had offered ‘to deliver personally a chess package’ to us. No such package ever existed, as we pointed out on page 44 of the December 1998 CHESS.

Hans Ree spent over 30 lines discussing this momentous episode on pages 92-93 of the 3/1999 New in Chess, and in the following issue (pages 97-98) we took four lines to give him ‘a copper-bottomed guarantee’ that Mr Whyld’s account was false. It was therefore a surprise to see that on pages 85-86 of the 6/2003 New in Chess Mr Ree returned to the subject, contradicting what he had written four years previously and muddling the facts. In e-mail messages he subsequently acknowledged to us that he had misrepresented matters, but it was only in March 2004 that he informed us of his refusal to make an amende honorable in print.

He added, though, that if we submitted a letter to New in Chess he would confirm that he had been wrong. Having received no confirmation from the magazine that it would publish anything from us, we prefer simply to mention the matter here. It is odd indeed that Mr Ree was willing to write about the ‘spy’ episode on two occasions when he was unfamiliar with the facts but not at all once he was acquainted with them.

(3262)

Regarding Mr Bernard Cafferty, see also Rebuttals.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.