Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [180] | next >> | Current column |

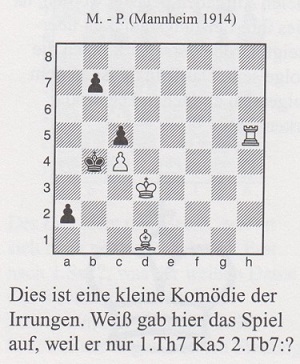

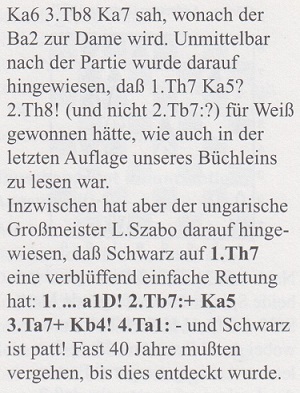

11389. An alleged Mieses v Post position (C.N. 11378)

C.N. 11378 had a reference to Kurt Richter’s book Der Schachpraktiker, and below is an excerpt from pages 95-96 of the fifth edition (Hollfeld, 1998):

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) sends the following from page 11 of the 1/1951 Deutsche Schachblätter (edited by Richter and with Szabó as a contributor) in an article entitled ‘Für und wider den Glossator’:

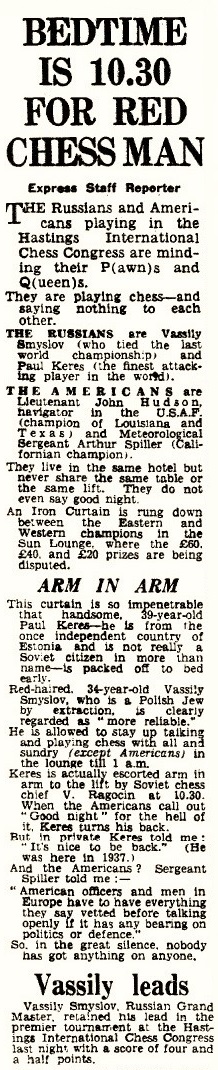

11390. Hastings, 1954-55

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has obtained permission from the Keystone Pictures archives for two photographs of Vassily Smyslov (Hastings, 1954-55) to be reproduced here:

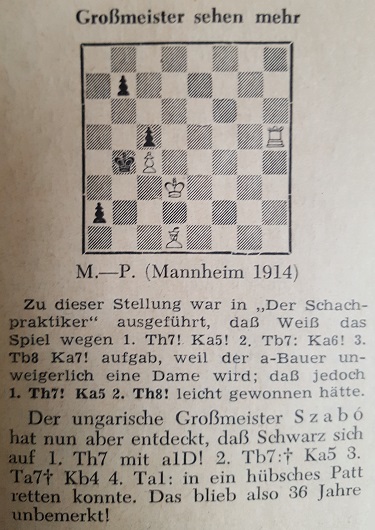

Another shot of Smyslov and Unzicker was on page 169 of CHESS, 8 January 1955:

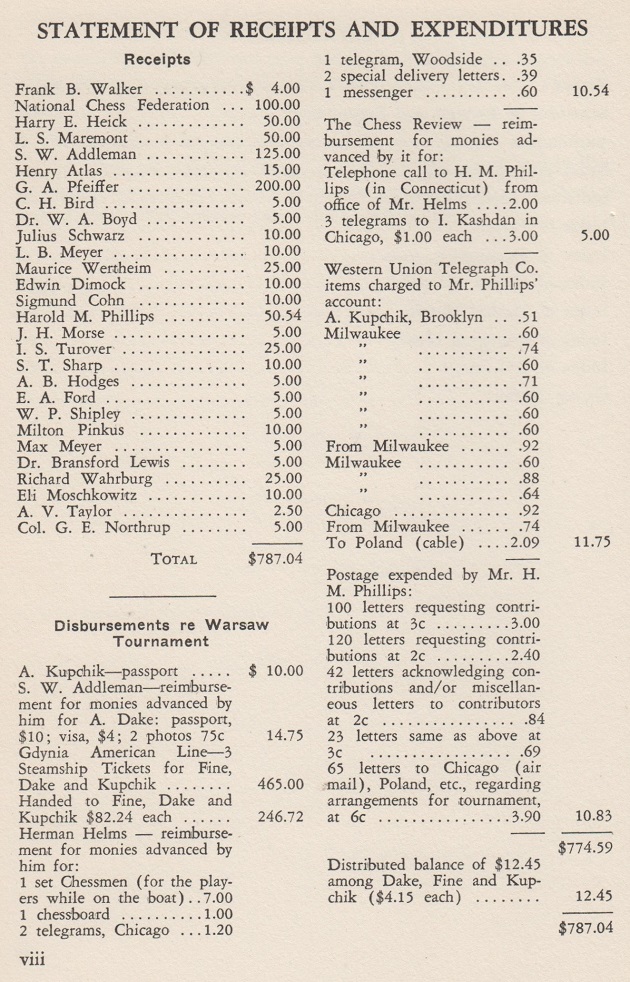

Page 184 of the 22 January 1955 issue of CHESS had an account of these press reports by Ralph Hewins:

Daily Express, 5 January 1955, page 5

Daily Express, 7 January 1955, page 5.

J. Hudson and A. Spiller participated, respectively, in the Major Section, Premier Reserves and in the Premier Reserves ‘A’, each obtaining 3½ points (BCM, February 1955, page 69).

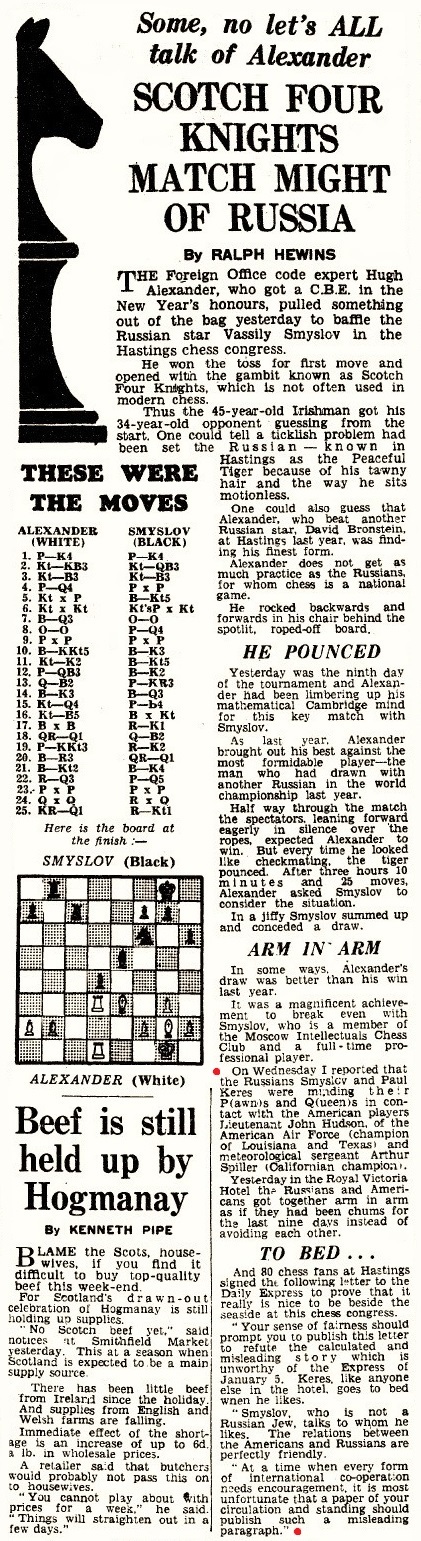

11391. Withers v Justice

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) draws attention to an 1844 game published on page 291 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1845 (volume six) and, with two brief notes, on page 37 of The Bristol Chess Club by J. Burt (Bristol, 1883):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 f5 4 dxe5 fxe4 5 Ng5 d5 6 e6 Nh6 7 Nc3 c6 8 f4 g6 9 h4 Be7 10 h5 Bxg5 11 fxg5 Nf5 12 g4 Ng3 13 Qd4 O-O 14 hxg6 Nxh1 15 gxh7+ Kxh7 16 Nxe4 dxe4 17 Qxe4+ Kg7 18 Bd3 and wins.

Our correspondent comments that after 18 Bd3 no mention was made of the possible line 18...Rf1+ 19 Bxf1 Qd1+ 20 Kxd1 Nf2+ 21 Ke2 Nxe4 ...

... with an extra piece against three pawns, although computer analysis suggests that the game should still be won by White.

11392. John Cochrane (C.N. 11102)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘The Royal Parks website makes it possible to search the burial register of Brompton Cemetery, and an image of the burial entry of John Cochrane shows that he was buried there on 8 March 1878. The address recorded was 12 Bryanston Street, Bryanston Square, and his age was given as 77, whereas 78 was specified in the death indexes of the General Register Office. The website also provides a link to an aerial view showing the location of the grave.

Does a memorial to Cochrane exist?’

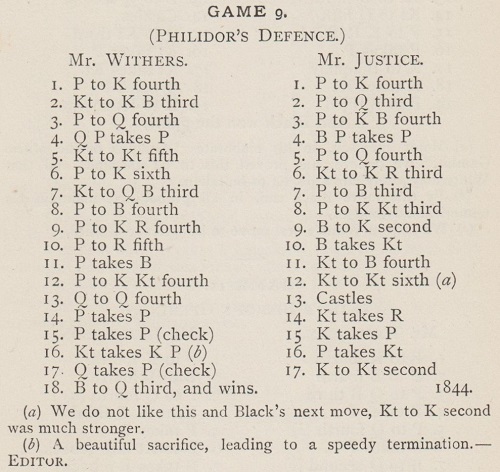

11393. US accounts for the 1935 Olympiad

Particularly detailed information regarding the US team is on page viii of Book of the Warsaw 1935 International Chess Team Tournament by Fred Reinfeld and Harold M. Phillips (New York, 1936):

At the time of the Olympiad, the cover price of the American Chess Bulletin and of Chess Review was $0.25.

11394. Reinfeld on annotating

On page v of the 1935 Warsaw Olympiad book mentioned in the previous item Fred Reinfeld wrote:

‘As I have occasion to analyse upwards of 500 games during the course of a year, my judgment tends at times to assume a routine or dogmatic character, and for this reason I found Mr Phillips’ unwillingness to take anything for granted, and his painstaking search for hidden resources, particularly invaluable.’

11395. A Pleci story

From an article by Jeremy Gaige, ‘The Ethics of Chess’, on page 106 of Chess Review, April 1961:

The story is related on, for instance, pages 82-83 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

No source was given, naturally, but the ease with which anyone can fill space with such stuff is demonstrated by this extract from a ‘Round the Chess World’ article by G. Koltanowski on page 77 of CHESS, 14 October 1935:

The episode was also related on page 18 of Najdorf: Life and Games by T. Lissowski and A. Mikhalchishin (London, 2005). The conclusion:

On the strict basis of authoritative accounts, and ideally with the game-score, how can the incident best be summarized in a brief paragraph?

11396. The altar of topicality

‘One cannot but deprecate this tendency to sacrifice good work on the altar of topicality ...’

That comes at the end of a short book review by Harry Golombek on pages 82-83 of the February 1955 BCM:

Golombek had high praise for Euwe’s book on the Candidates’ tournament, Schach-Elite im Kampf, on page 165 of the May 1955 BCM.

11397. Lasker v Capablanca in 1906

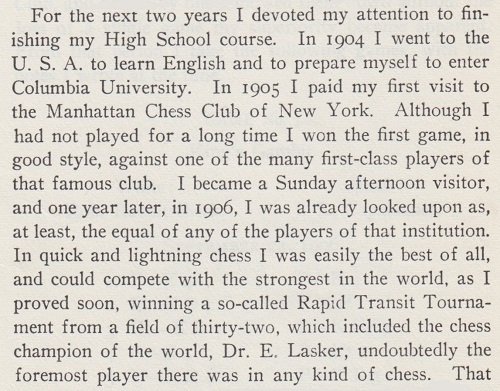

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) raises the topic of the 1906 rapid transit tournament at the Manhattan Chess Club, New York referred to by Capablanca towards the end of Chapter II (page numbers vary) of My Chess Career (London, 1920):

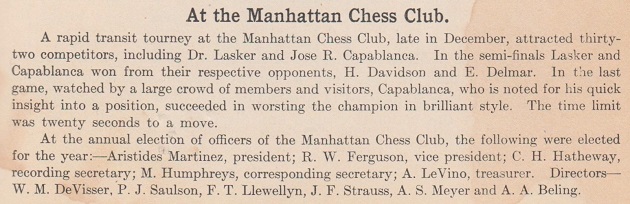

A reference to the tournament on page 35 of the February 1907 American Chess Bulletin was shown in C.N. 10421:

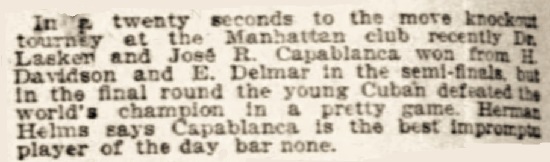

From page 8 of the Chicago Tribune, 20 January 1907:

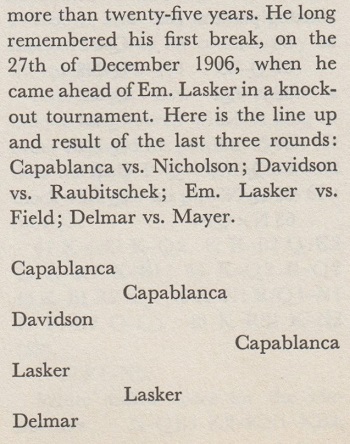

On page 100 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975) the semi-final pairings against Davidson and Delmar were given the other way round:

A later report on page 5 of the New York Evening Post, 23 January 1907:

No earlier item in the Evening Post specifically on the December 1906 tournament has yet been found.

An assessment of Lasker and Capablanca was provided by Walter Penn Shipley on page 9 of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 January 1907:

Mr Rojas Barrios notes that in secondary sources the tournament which brought together Lasker and Capablanca in December 1906 is sometimes misdated April 1906, one example being page 28 of El ajedrez en Cuba by José Luis Barreras Meriño (Havana, 2002):

The source indicated (page 11 of the book on the Havana, 1966 Olympiad) had given no date for the rapid transit tournament:

As our correspondent also points out, the April 1906 event was at the Rice Chess Club. From pages 61-63 of the April 1906 American Chess Bulletin:

See too page 309 of our book on Capablanca.

C.N. 6077 noted that the remark by Lasker about Capablanca’s freedom from error, mentioned in the two Cuban books above, was supposedly made after their ten-game rapid transit match in Berlin in 1914. See Fast Chess.

11398. George Henry Mackenzie and James Parker Barnett

From John S. Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

‘Olimpiu G. Urcan and I are working on a biography and game collection of George H. Mackenzie; although it is unlikely to be published for several years, we have already collected over 1,000 of his games.

When drafting material about Mackenzie’s play in the United States in the first few years after the Civil War, and in dealing with his opponents, we ran across an article about Dr James Parker Barnett. Your readers may like to see our draft account, which comes after a description of Mackenzie’s first-round match with Stanley at the 1866 New York Chess Club tournament:

“His most trying challenge met, Mackenzie faced Dr James Parker Barnett in the second round. His opponent had the benefit of Worrall resigning to him in the first round without a game played, although Barnett would have been favored to win against almost anyone. Six years older than Mackenzie, Barnett was born and raised in New York City. A product of the Morphy boom, he started playing publicly in the late 1850s, when he was living and practicing medicine in Brooklyn. In 1860 he made it to the final round of a chess tournament at the Morphy Chess Rooms, but lost to the now dead James A. Leonard. Absent from chess during the war, Barnett returned with the 1866 New York Chess Club tournament, and went on to play offhand and tournament games at the Café Europa and Café International later in the decade and into the mid-1870s. Hazeltine, after Frank Teed told him of Barnett’s death in 1886, remembered Barnett from his earliest days, writing that Barnett ‘possessed the happy combination of a lively imagination and unflinching courage, coupled with perfect suavity of manner whether victor or vanquished. Consequently, his game was at once strong, steady and brilliant’. Mackenzie himself believed, according to Alexander Sellman, that at one point Barnett was ‘one of the strongest players of the country’. [See endnote 1.]

Barnett received his college degree from the University of the City of New York in 1848. He graduated from Dartmouth Medical College in 1854. His academic road, impressive as it was, was neither smooth nor easy, although not because of any academic failing on his part. Barnett was one of three children of James Barnett, Sr, a self-made businessman who made his fortune along New York’s East River supplying metal services for the packet ship companies. Barnett’s mother was Eliza Beaumont, also from New York. In October 1850 Barnett was in his third and final year at Columbia School of Physicians and Surgeons when he was grilled by his professors over his racial background, as allegations had been made earlier by a never-identified ‘Southern gentleman’ that Columbia harbored ‘colored students’, naming among them Barnett. Barnett was expelled subsequently by Columbia for failure to disclose his African ‘blood’ at the time of his application. Barnett’s father hired the grandson of John Jay, a well-known abolitionist lawyer and Columbia graduate, to represent the medical student in his appeal against expulsion. According to Barnett, Sr, his son was in fact of mixed Native-American and White ancestry, which explained his darker complexion. This, however, hardly explained why the younger Barnett was apparently unaware of any such Native-American ancestry.

What few facts remain are not in favor of the elder Barnett’s allegation of his son’s supposed Native-American ancestry. Barnett’s sister Malvina married a prominent black abolitionist and physician, the first to hold such a degree. In addition, although unbeknownst to Columbia, the 1850 Federal Census as well as the 1855 New York State Census identified Barnett and his family as Mulatto, although later censuses marked them as White. (Census records at the time reflected a highly suspect, subjective classification, as the census enumerators were left to their own devices for assessing race.) In any event, the appeal was futile, as Columbia had no intention of relenting. The faculty and trustees, however, seeking to end the litigation, offered to examine Barnett, and subsequently found him fit to practice medicine. His degree, despite his tested competence, was eventually blocked by the Regents of the University of New York on the technical, and exceedingly hypocritical, grounds that he had failed to satisfy a lecture requirement that, in fact, he had been barred from completing. This dismal conclusion did not end Barnett’s career, as he went on to earn a medical degree from Dartmouth and practiced medicine in the greater New York metropolitan area for the rest of his life, respected by his friends and colleagues.” [See endnote 2.]

Endnotes:

“1. See Mason, p. 296. ‘possessed the happy combination …’ New York Clipper, March 6, 1886. ‘One of the strongest players …’ Baltimore American, April 18, 1886. See also Leonard, Hilbert, pp. 34-37.

2. Barnett’s full name and degrees appear in the General Catalog of Dartmouth College (Hanover, New Hampshire, 1890), pp. 127, 178. The detailed and compelling history of his fight against expulsion by Columbia’s medical school appears in the article ‘Blurring the Lines: James Parker Barnett, Racial Passing, and Invisible Early Black Students at Columbia University’ by Ciara Keane (accessed June 17, 2019).”

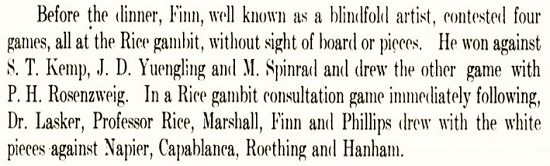

A small sketch of James Parker Barnett is on page 172 of Brentano’s Chess Monthly, August 1881. Below we reproduce with permission a photograph of him forwarded by Dr Hilbert and owned by the Cleveland Public Library:

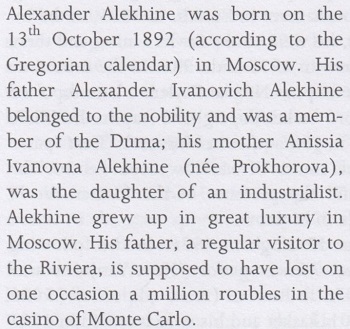

11399. Alekhine’s date of birth

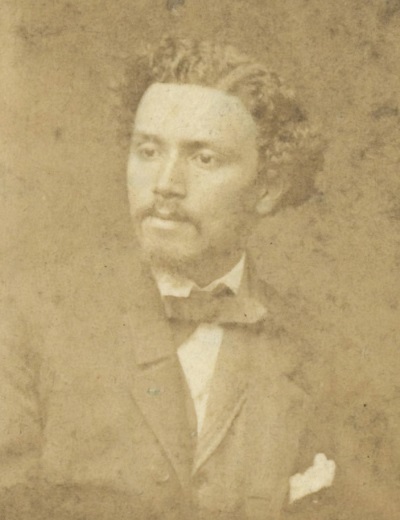

Pages 20-21 of the 21/1972 issue of Shakhmaty

As mentioned in C.N.s 4719, 4739 and 5782 (see When Was Alekhine Born?), a clear copy of Alekhine’s birth certificate is sought.

The opening paragraph of our feature article:

Alekhine’s birth-date is often given as 1 November 1892, but we are aware of no authoritative book published in the past 20 years or so which deviates from the ‘established’ date of 31 October 1892 (Gregorian calendar); this is the equivalent of 19 October 1892 in the Julian calendar, the gap in the nineteenth century being 12 days, and not 13.

Writers still go astray, and below is the poor start to a section on Alekhine on page 78 of The Big Book of World Chess Championships by Andre Schulz (Alkmaar, 2016):

Regarding the final sentence, no discernible purpose is served by mentioning what Alekhine’s father ‘is supposed to have lost on one occasion’.

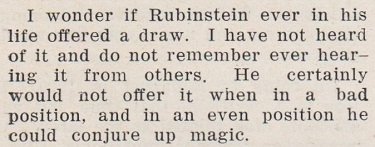

11400. Draw offers

On the subject of draws, C.N. 2549 (see page 359 of A Chess Omnibus) quoted this remark on Rubinstein by L. Steiner on page 54 of the March 1961 Chess World:

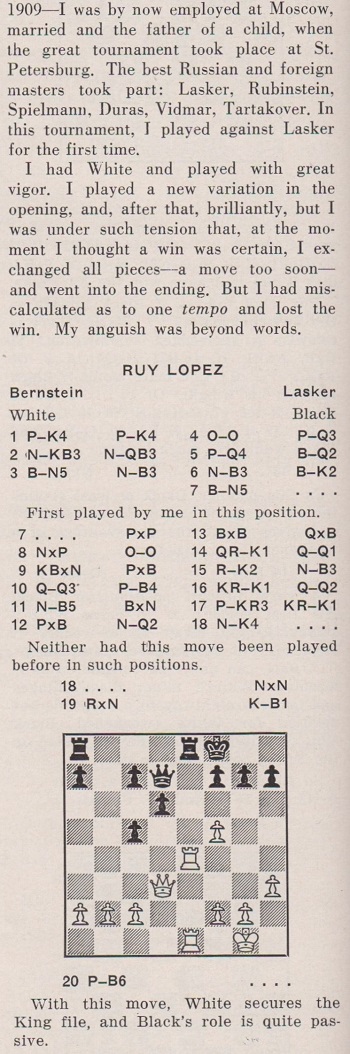

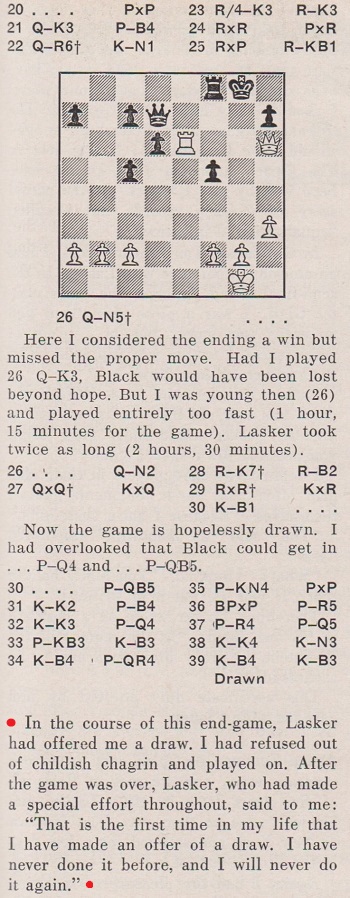

A claim about Emanuel Lasker’s practice appeared in ‘My Encounters with Lasker’ by Ossip Bernstein on pages 202-204 of the July 1955 Chess Review:

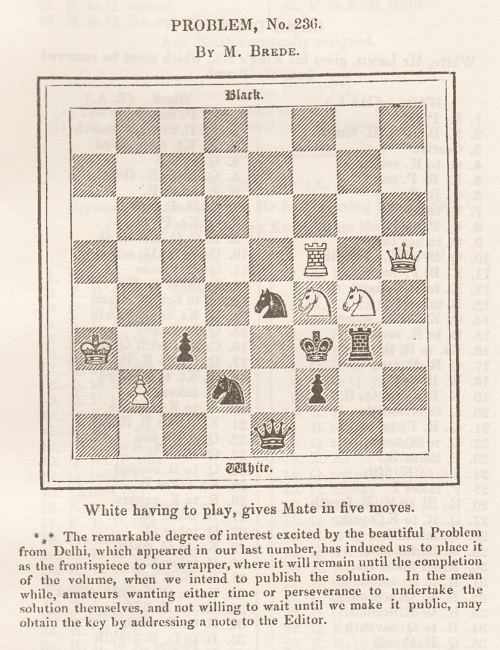

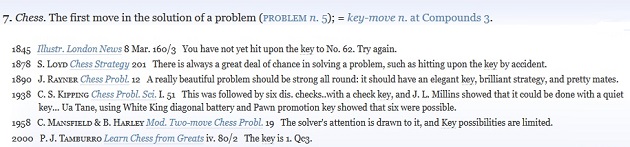

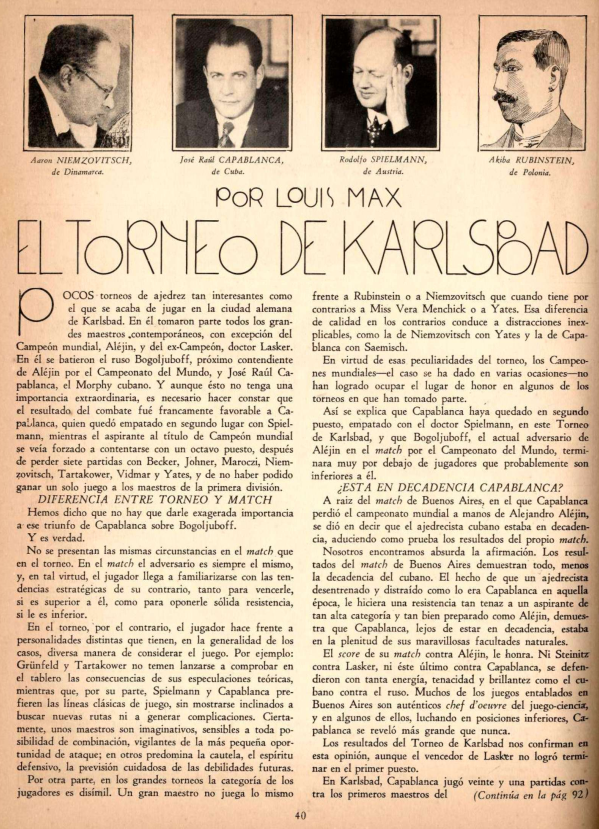

11401. Keys and

key-moves (C.N. 5294)

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘On pages xxix-xxx of volume one of A Treatise on the Game of Chess (London, 1808) J.H. Sarratt introduced his “critical and remarkable situations, or ends of games”, writing:

“These situations will not greatly improve amateurs, unless they attempt to find out the method of winning without looking at the solution; the author has therefore deemed it eligible to insert the situations in the first volume, and the solutions in the second: and he earnestly recommends amateurs to seek diligently for the proper moves, without having recourse to the key: the improvement which they will derive from adhering to that system will amply compensate them for their trouble.”’

Our correspondent also draws attention to the word ‘key’ on page 65 of volume six (1845) of the Chess Player's Chronicle:

Below are the chess citations for ‘key’ and ‘key-move’ in the online Oxford English Dictionary:

A reference will be added in Earliest Occurrences of Chess Terms.

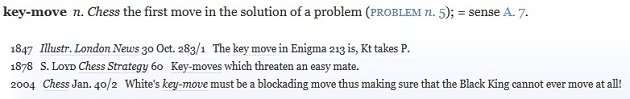

11402. Carlsbad, 1929

An article by Louis Max on pages 40 and 92 of Social, October 1929 has been submitted by Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba):

Apart from obvious factual errors, the article is notable for its heavy pro-Capablanca slant.

11403. Dutch players (C.N.s 5408 & 5416)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) draws attention to Adriaan Plomp’s article about B.W. Blijdenstein, which identifies him as the player active in London in 1859-61, as well as Dutch events in the 1870s, whereas the participant in Amsterdam, 1851 was W.J. Blijdenstein.

11404. Cased image (C.N.s 6018 & 7390)

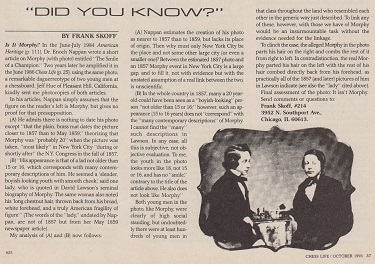

This picture was also discussed on page 37 of the October 1993 Chess Life by Frank Skoff, who concluded that it did not feature Paul Morphy.

11405. A Countess from Hong Kong

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has acquired permission from Mondadori for us to reproduce a photograph taken during the shooting of the 1967 film A Countess from Hong Kong:

Marlon Brando, Charlie Chaplin, Sophia Loren

11406. Frank James Marshall

‘The name of Marshall is associated with the unexpected in chess. No-one, not even Morphy, has won more brilliant games, many of them brought about from most unpromising looking positions.’

Source: page 58 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929).

11407. Lasker v Schlechter

A paragraph about Emanuel Lasker on page 97 of A Short History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1963):

The writer of these references to 12 games, instead of ten, in the 1910 Lasker v Schlechter match was B. Goulding Brown.

The quoted remark about ‘charming an attack out of nothing’ was on page 218 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, August-September 1906, in a note to Schlechter’s 29...c5 against Rubinstein, Ostend, 1906:

Position after 29 Nf2-d1

11408. Threats

‘We can gain nothing in chess except by means of threats.’

That observation is on page 69 of How Not to Play Chess by E. Znosko-Borovsky (London, 1931):

A dissenting note appeared in a book review by Charles De Vide on page 73 of the April 1932 American Chess Bulletin:

11409. G.H.D. Gossip

On the question of whether G.H.D. Gossip’s second forename was Hatfield or Hatfeild, an extensive contribution from Neil Hickman (Hardingham, England) has been added to our feature article.

11410. Alekhine in the Second World War

A wild claim on page 96 of Le grand livre des échecs by Camil Seneca and Adolivio Capece (Paris, 1977):

‘Quand la Seconde Guerre mondiale éclata, Alekhine, étant naturalisé français, fut appelé sous les drapeaux et engagé dans les services secrets, surtout parce qu’il parlait et écrivait parfaitement dix langues!’

11411. Incorrigible writers about chess

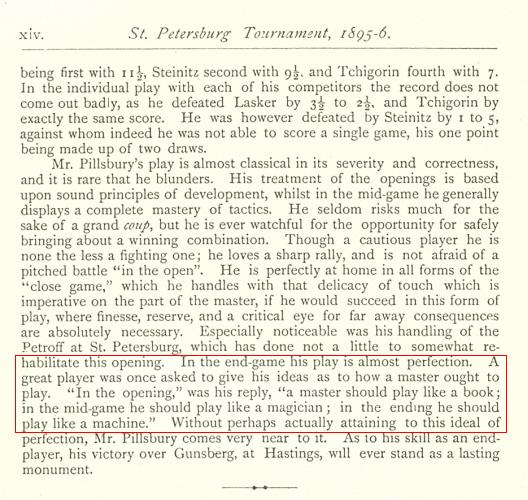

It is now over 36 years since we queried, in C.N. 325, the above text from page 24 of The Chess Beat by Larry Evans (Oxford, 1982), and it is over 13 years since a correspondent, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina), pointed out, in C.N. 4156, that the remark had been published well before Rudolf Spielmann’s chess career began, i.e. on page xiv of The Games of the St Petersburg Tournament 1895-96 by J. Mason and W.H.K. Pollock (Leeds, 1896):

Nonetheless, misattribution to Spielmann continues, and Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes two occurrences on Twitter on 17 July 2019:

In the second screen-shot we have deleted the photograph (Spielmann v Alatortsev) because, as shown in Copying, the French website (of Mr Philippe Dornbusch) has a habit of taking pictures and other material without permission or acknowledgement. Even the words ‘an Austrian-Jewish chess player of the romantic school, and chess writer’ are a direct copy from Spielmann’s Wikipedia entry.

Further details about the misattribution of the quote to Spielmann are given in Chess: the Need for Sources.

11412. Alexander McDonnell

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘The following review of William Greenwood Walker’s A Selection of Games of Chess, actually Played in London by the late Alexander McDonnell, Esq., appeared in the Metropolitan Magazine, October 1836, page 46. The article is also in large measure a tribute to Alexander McDonnell, who had recently died.

“When we read this title we were struck with consternation at the word ‘late’, for it was but a few short months ago that we ourselves contended with Mr M’Donnel, certainly with more profit than success. Alas! it is no odds now what odds he gave us then, for death, too truly, makes all things even. However, we cannot – it would be injustice to refrain from bearing our testimony to the gentlemanly deportment, the urbane manners, and the high intellect of this first of English chessplayers. The evenness of his nature was singular; – he had neither the proud reserve of success, nor the moroseness of disappointment. He could not but be conscious of his superiority, but he wore it with the most unpretending air of good-humour that we ever beheld. He was very unlike many of his contemporaries, greedy of the paltry gain of the stakes, fearful to play with a competitor of approximating excellence, or sullen and taciturn in his manners. We are sorry to say that the besetting sin of some, a few, of the principal chessplayers, was a want of suavity in the general tone of their manners, to those beneath them in skill supercilious, of their equals jealous, of those above them envious. But none of this could M’Donnel be, for he was, in the most lofty sense of the word, a gentleman. But to the work before us. The chessplaying world are much indebted to Mr Walker for putting these very excellent games upon record. In them the observer will see all the variations of the most scientific plans, – the long calculation, the sudden surprise, the well-concealed ambush. Many of the games are exquisite, both as to the skill of the attack and the defence; and we conceive nothing more likely to improve a student of chess than sitting down quietly and playing them over on the board, con amore, as they are set down in the work. Really, we recommend this volume to general acceptation.”

The writer of the review, Edward Howard (died 1841), was the sub-editor of the Metropolitan Magazine, in addition to being a novelist. He was a member of the Westminster Chess Club and was mentioned on page 3 of the Morning Post, 3 February 1835 in connection with the visit to the club of the Turkish Ambassador. Only a single game was played on the occasion, when “the Pacha’s secretary” beat Howard “in good style”. However, the latter was described as “a player to whom a first-rate can give a rook”.’

11413. Capablanca and Caparrós

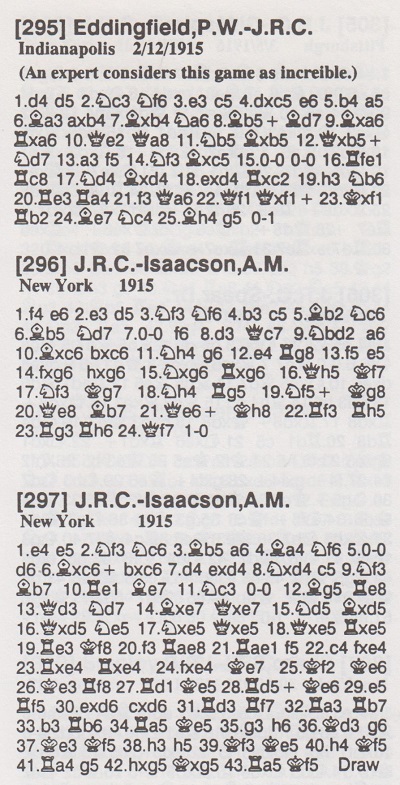

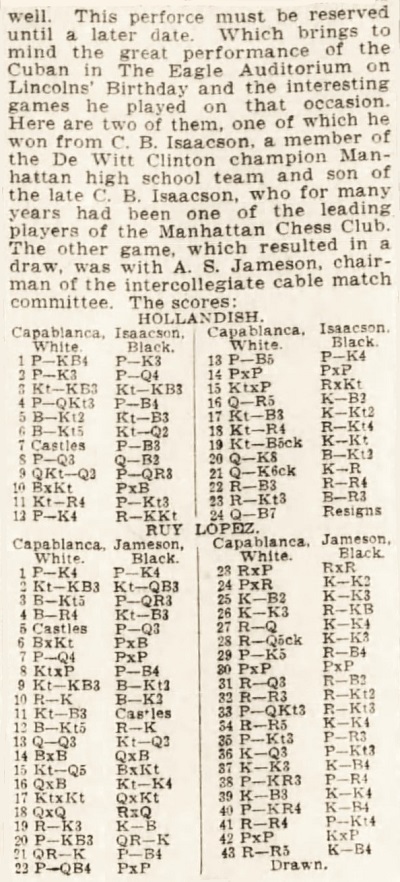

From page 197 of The Games of José Raúl Capablanca by Rogelio Caparrós (Dallas, 1994):

The same shambles was in the earlier editions of the book, published in Yorklyn, 1991 (pages 211-212) and in Barcelona, 1993 (page 159).

Regarding the ‘increible’ game against Eddingfield, see C.N. 4996.

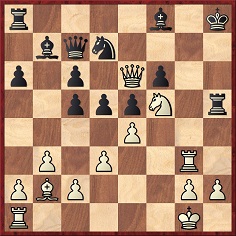

The Bird’s Opening game was discussed in C.N. 3594, which pointed out that the version proffered by Caparrós would mean that Capablanca missed 24 Qg8 mate, whereas it may seem obvious that Black played 23...Bh6 and not 23...Rh6.

Position after 23 Rf3-g3

C.N. 3594 added that the only source given by Caparrós for the game was ‘Pittsburgh papers’, but now Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) provides the chess column on page 3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10 June 1915:

Our correspondent notes that in the Bird’s Opening game Black was C.B. Isaacson, and not ‘A.M.’ as stated by Caparrós, and that his 23rd move was indeed given as 23...Bh6. Moreover, the Ruy López game which Caparrós also ascribed to ‘A.M. Isaacson’ was against A.S. Jameson.

The Capablanca v Jameson game-score was included in the coverage of the display in the American Chess Bulletin, March 1915, pages 42-46, with ‘A. Stedman Jameson’ on page 43 and ‘A.J. Jameson’ on page 45.

The exhibition took place in the auditorium of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, NY) on 12 February 1915. The Bulletin reported that Capablanca ‘was on his feet fully seven hours’, facing 84 opponents on 65 boards and scoring +48 –5 =12. Spectators joined in the deliberations, and ‘Capablanca, at a conservative estimate, had opposed to him the wits of perhaps 200 persons’. For further information, and particularly on the time consumed, see Capablanca’s Simultaneous Displays.

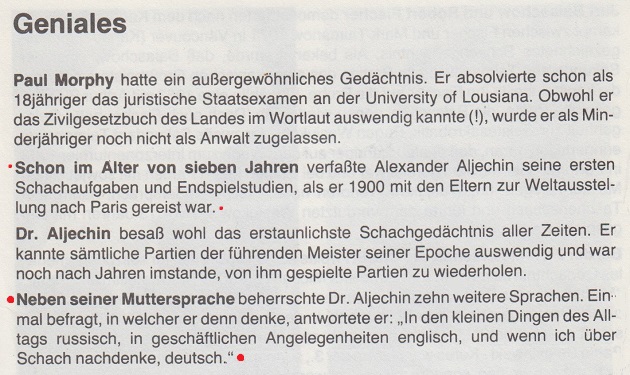

11414. Claims about Alekhine (C.N. 11410)

In the fourth item below, from page 69 of Das Spiel der Könige by Alfred Diel (Bamberg, 1983), the unsourced ‘Einmal’ remark about languages which is attributed to Alekhine has no reference to French:

When C.N. 1160 discussed the book, unenthusiastically, mention was made of the peculiar claim in the second item, about Alekhine and the 1900 Paris Exposition.

11415. The two-mover

‘Unfortunately the two-mover is virtually exhausted after all these centuries.’

Source: page 33 of The Chess Beat by Larry Evans (Oxford, 1982). The syndicated column can be viewed online (Reno Gazette-Journal, 31 December 1977, page 13).

After C.N. 328 quoted the remark, two readers responded in C.N. 461. R.F. Bradley (Donaghadee, Northern Ireland) commented that the two-mover could hardly be exhausted when such compositions as the following were appearing:

K. Braithwaite (Canada), the Problemist, November 1982

Key: 1 Bh2. ‘This brilliant move allows the two black king flights – with a difference. The white king is in check to the rook’ (R.F. Bradley).

Michael McDowell (Newtownards, Northern Ireland) wrote regarding Larry Evans:

‘His statement contains an historical inaccuracy. The modern two-mover, in which emphasis is placed on thematic content, dates from the middle of the nineteenth century, when composers began to produce problems showing definite ideas instead of the normal collection of unrelated mates. Even up to the 1840s, little attention was paid to the two-mover. Alexandre’s Collection des plus beaux problèmes d’échecs (1846) contains 2,020 problems, of which 94, or 4.6%, are two-movers. Compare this with the FIDE Album 1945-55, which contains 1,981 problems, two-movers numbering 543, or 32%. (Figures quoted from The Two-move Chess Problem 1285-1846 by C.M. Champion, the Problemist September and November 1969.)’

11416. Misattribution

As pointed out in C.N. 348, a syndicated column by Larry Evans reproduced on page 40 of his anthology The Chess Beat ascribed the phrase ‘I think, therefore I am’ to Pascal.

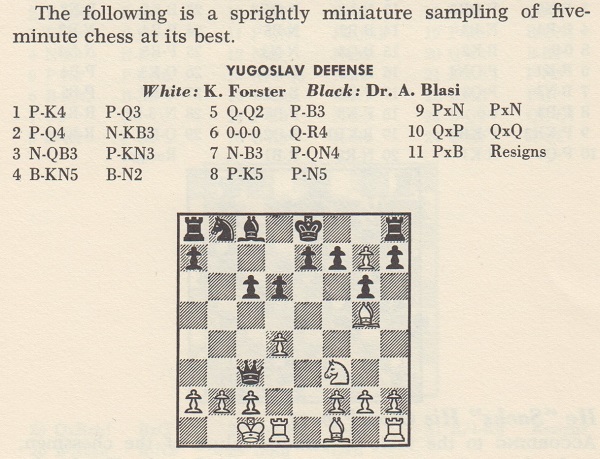

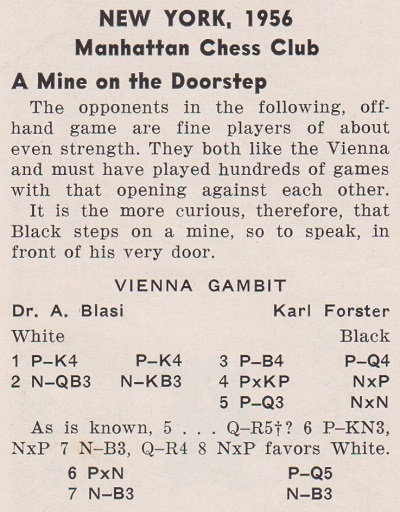

11417. Fast chess

Page 167 of All About Chess by Al Horowitz (New York, 1971) has a game that we have not seen in databases:

1 e4 d6 2 d4 Nf6 3 Nc3 g6 4 Bg5 Bg7 5 Qd2 c6 6 O-O-O Qa5 7 Nf3 b5 8 e5 b4 9 exf6 bxc3 10 Qxc3

10...Qxc3 11 fxg7 Resigns.

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) points out Horowitz’s article was originally published in the Saturday Review of the New York Times, 14 February 1969, page 14. The date and venue of the game have not been found.

Our correspondent adds two other specimens of fast chess:

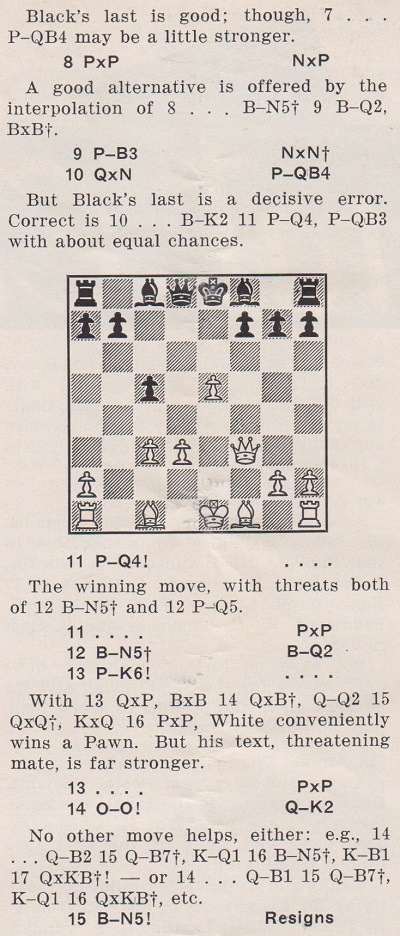

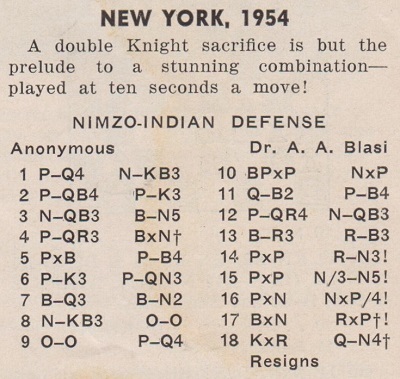

Chess Review, October 1956, page 315

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 d5 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 d3 Nxc3 6 bxc3 d4 7 Nf3 Nc6 8 cxd4 Nxd4 9 c3 Nxf3+ 10 Qxf3 c5 11 d4 cxd4 12 Bb5+ Bd7

13 e6 fxe6 14 O-O Qe7 15 Bg5 Resigns.

Chess Review, May 1954, page 129

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 a3 Bxc3+ 5 bxc3 c5 6 e3 b6 7 Bd3 Bb7 8 Nf3 O-O 9 O-O d5 10 cxd5 Nxd5 11 Qc2 f5 12 a4 Nc6 13 Ba3 Rf6 14 dxc5 Rg6 15 cxb6

15...Ncb4 16 cxb4 Nxb4 17 Bxb4 Rxg2+ 18 Kxg2 Qg5+ 19 White resigns.

Mr Bauzá Mercére notes too the reference to ‘Dr Anthony Blasi of New York’ on page 218 of the July 1954 Chess Review.

11418. Combinations

From the Introduction to Logical Chess Move by Move by Irving Chernev (various editions, with different page numbers):

‘The master does not search for combinations. He creates the conditions that make it possible for them to appear.’

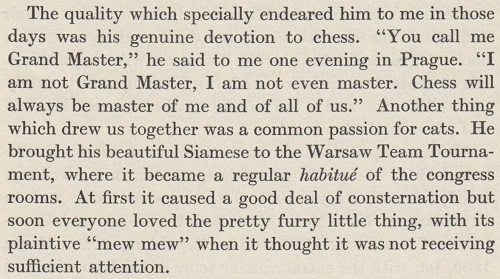

11419. Masters and cats

An excerpt from page 113 of Kings of Chess by William Winter (London, 1954), in the chapter on Alekhine:

The ‘I am not Grand Master’ remark was discussed in C.N. 5525.

11420. Alekhine v Euwe match, 1926-27

From page 177 of the book mentioned in the previous item.

‘It is possible that Alekhine had not fully trained for the encounter and that he was rather too appreciative of Dutch hospitality, but nothing can detract from the all-round excellence of Euwe’s play.’

When did explicit references to Alekhine’s excessive alcohol consumption begin to appear?

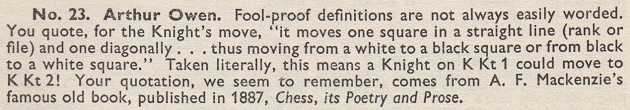

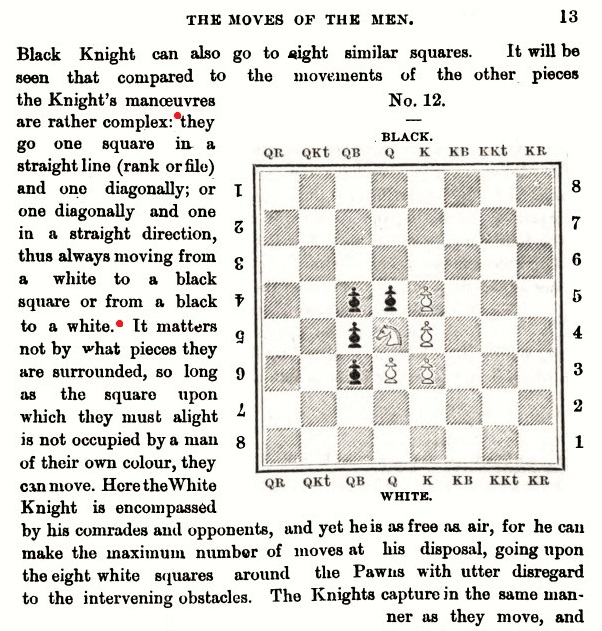

11421. The knight move

An addition to The Knight Challenge comes from page 136 of the May 1953 BCM, in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column:

The exact wording in A.F. Mackenzie’s book:

That comes from the section entitled ‘The Elements of Chess’. The full explanation of the knight’s move (pages 12-14, with three diagrams) left no ambiguity.

11422. Non-Spielmann quote (C.N. 11411)

From the Wikipedia page on Rudolf Spielmann:

Spielmann’s forename and surname are misspelled in a dire Wikipedia article entitled ‘Romantic chess’ which includes, for instance, a reference to ‘the 1930s when hypermodernism began to become popular’.

11423. Immortal

In his article ‘The Romantic Art in Chess’ on pages 15-16 of the January 1969 Chess Life, Pal Benko discussed The Immortal Game and The Immortal Chess Problem. Regarding the composition by K. Bayer (‘C. Meyer’) he wrote:

‘This problem excited its composer’s contemporaries no doubt because of the sheer quantity of material sacrificed in order to give mate with the last pawn. In a way it resembles the classical tragedy: almost all the “actors” die before the play is over. It is certainly an extraordinary idea, but, for today’s taste, “how” is of greater significance than “how much”.’

11424. Elijah Williams

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes regarding Elijah Williams:

‘Personal biography

Elijah Williams was born on 7 November 1809 and baptized on 3 June 1810 at a Calvinistic Methodist chapel known as the Tabernacle in Penn Street, Bristol (National Archives, RG 4/1360), a son of Elijah Williams and his wife Sarah, of the parish of St Stephen in Bristol. The same register also contains baptism entries for two siblings, Ann Baynton Williams (1805) and Joseph Baynton Williams (1807).

Father and son were sometimes referred to as Elijah Williams senior and junior. The occupation of Elijah Williams senior at the time of his son’s birth is not known. An “Elijah Williams, of the city of Bristol, upholsterer, dealer and chapman” was declared bankrupt in the London Gazette of 30 May 1815, page 1029, but it remains to be established whether it was the same person.

Page 183 of Mathews’s Annual Bristol Directory for 1836 shows that by that time the chessplayer’s father was a landing waiter, at 15 Portland Street, Kingsdown. It was a responsible customs job, overseeing the landing of goods from vessels. On the next line is an entry for Elijah Williams junior, a surgeon, of 24 Union Street.

Williams qualified as a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA), to whom I am grateful for providing the following information from their “Court of Examiners’ Candidates Qualification Entry Book”. This shows that he qualified from Apothecaries’ Hall on 16 December 1830, having been examined and approved. He had been an apprentice by an indenture of 17 December 1824 to Messrs Henry Russ Grant and Edwin Grant, Bristol apothecaries, for five years. His masters also provided a testimonial of his moral character. He had attended lectures in Chemistry, Materia Medica and Botany, Anatomy and Physiology, Anatomical Demonstrations, and the Principles and Practice of Medicine, while his hospital attendance had included nine months at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, two courses of lectures on Midwifery and two courses of Clinical lectures. The record also confirms his date of birth as 7 November 1809.

His occupation was surgeon at the time of the 1841 census, when he was listed at Stokes Croft, Bristol (National Archives, HO 107 372/2, folio 11).

His brother, Joseph Baynton Williams, was declared bankrupt in the London Gazette of 15 October 1841, page 2558; he was described as a wholesale and retail ironmonger, dealer and chapman, of the city of Bristol. At other times he was a solicitor, having been articled on 26 October 1825 to William Baynton, of Bristol (National Archives, KB 106/11) and on 20 May 1829, for the remainder of the term, to Edward John Horton, of Furnival’s Inn, Holborn (National Archives, KB 106/14). A William Baynton of Clifton appears in the list of subscribers appended to Elijah Williams’ 1845 book Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club. In 1846 Joseph was in London, but spent some time in the debtors’ prison for London and Middlesex, as is shown by a notice regarding his insolvency in the London Gazette of 1 May 1846, page 1620. He eventually surmounted these financial difficulties. By coincidence or design, Joseph’s presence in London was close to the time when Elijah moved to the capital.

Elijah Williams’ first marriage took place on 9 April 1844 in the church of St Mary Kirkdale, near Liverpool, his bride being Amelia Cassin, “youngest daughter of T. Cassin, Esq.”, and the service performed by Rev. D. James, according to the Manchester Courier, 13 April 1844, page 6.

Elijah Williams was described as a surgeon, of Bristol, which suggests that he was in Kirkdale just for the wedding rather than as part of a longer stay in Lancashire. A Diocese of Chester marriage licence allegation, dated 6 April 1844, indicates that Amelia was a spinster, of the parish of Walton on the Hill, and Elijah a bachelor. Her surname in that document was spelt Casson.

An Amelia Cassin is to be found in the 1841 census in the expected locality at Devonshire Place in the parish of Everton, her age indicated in the range 30-34 (National Archives, HO 107 519/3, folio 44). In the same household were a John Cassin, merchant – possibly a brother – and two small children.

The marriage was soon ended by death, though not before it bore fruit. The parish register of St Mark, Kennington (South London) shows that a daughter, Mary Cassin Williams, was born on 26 August 1846 and baptized there on 11 October. In 1850, Elijah married again as a widower, so Amelia is assumed to have died in the intervening period. There is an entry in the General Register Office’s index of deaths for Amelia Williams, aged 36, in the district of Lambeth for the December 1846 quarter (volume four, page 200), which, if it were the correct entry, would mean that she died only a few months after the birth of the child. Their daughter died in St Leonards-on-Sea on 22 November 1931 at the age of 85 (National Probate Calendar).

His second marriage was recorded in the register of St Mary’s, Lambeth, on 21 November 1850, and was by licence. The groom was described as Elijah Williams junior, widower, a surgeon, of 56 Walnuttree Walk, son of Elijah Williams, gentleman, and the bride as Mary Ann Robina Moore Hodson, a spinster, of 32 Dodington Grove, a daughter of John Hodson, deceased, a clerk in the Audit Office.

It is at 32 Dodington Grove, Newington, that the couple are to be found in the 1851 census (National Archives, HO 107 1568, folio 6). This was the Hodsons’ family home, and was headed by Williams’ mother-in-law, Mary Hodson, who lived off “funded property”, having been born in Barbados. Williams was described as a lodger, a non-practising surgeon. His wife was born in Middlesex, and her age was given as 28.

In a rare, if not unique, physical description of Williams, he was noted by H.A. Kennedy in an article entitled “A Desultory Ramble with the Chess-men”, which appeared on page 47 of Charles Tomlinson’s Chess Player’s Annual (London, 1856) as having “burly form, light hair and eyes, and florid complexion”.

According to the General Register Office’s index of deaths, Elijah Williams senior died in the final quarter of 1853 in the registration district of Bedminster, Somerset, his age given as 77 (volume 5c, page 501). Page 8 of the Bristol Mercury, 24 December 1853 states that he died on 6 December “at his residence at Portishead, after a long illness”. His will (National Archives, PROB 11/2187/23) describes him as a gentleman of Portishead, Somerset. He named as his executors two gentlemen of Bristol, who were instructed to hold on trust his estate, which included freehold property on the Broad Quay and in Portland Street, Bristol, and freehold and leasehold property at Portishead. His daughter, Ann Baynton Williams, was to receive the rents and profits of his estate for her natural life. After her decease, the rents and profits were to go to his son, Elijah Williams, and after his death to his four grandchildren, including Mary Cassin Williams, “share and share alike” as tenants in common. The will, including a codicil which was added on 15 June 1853, was proved on 3 February 1854.

A weakness in the provisions in the will was that, in the event of the early death of Elijah Williams junior, his widow would not benefit; nor would the children except in the long term, which meant that all of them would be unprovided for. That swiftly happened.

The tragedy of Williams’ end was reported in “Obituary of Eminent Persons” in the Illustrated London News, 30 September 1854, page 299. It tells the story of his death from cholera on 8 September 1854 at Charing Cross Hospital. He had been “seized with violent pains near Northumberland House”, which no longer exists today, but stood then at the extreme west end of the Strand, on the south side. He had “walked to town”, so his last fateful journey must have taken him from Kennington to the north side of the Thames and thence to the west end of the Strand. A friend advised him to go to Charing Cross Hospital. The article, presumably by Howard Staunton, was written sympathetically and included a plea for charitable support for Williams’ widow:

“We urge the claims of the widow the more earnestly because we are acquainted with her truly deplorable position.”

The parish register of St Mark, Kennington records the baptisms of two other daughters, Ada Ellen on 23 July 1852, the address entered as Surrey Place, born on 4 October 1851, and Blanch Hodson, on 25 October 1854, the address given as South Street, Kennington Common, “sd to be born 14 Novr. 1852”. A son, Elijah, born on 18 January 1854, was baptized there on 5 November, the father’s occupation still entered as surgeon and the address given as Hope Terrace, South Street. Consequently, the remark in the obituary that Williams left “a widow and four young children” can be corroborated.

For the last child, Elijah, a place was obtained at the Infant Orphan Asylum, Wanstead. He led a long and prosperous life, becoming a chartered accountant and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He died at Runfold Place, near Farnham, Surrey, on 1 February 1937 (source: National Probate Calendar). The 1901 census (National Archives, RG 13/200, folio 123) shows that he married and had several children, so there is every possibility that descendants of Elijah Williams the chessplayer are alive today.

As a player and an author

An assessment of Williams’ chess career appeared in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1856, pages 125-128, then edited by R.B. Brien, in an article entitled “Mr Williams as a Chess-Player”. About his style of play it stated:

“If he had any defect in play, it was not over-caution, but a striving for some small advantage, which could hardly be gained without danger. He played, in short, more for little permutations of force and position than in the spirit of high art, although he did not neglect greater things when they came in his way. No-one held to an advantage more firmly than he did, nothing generally was better than the unflinching courage and perseverance which he displayed under difficulties.”

The article notes his early involvement with the Bristol Chess Club and his position as President, mentioning that the club mustered more than 60 members within three weeks of its formation. This springing “into manhood almost at its birth” the author ascribes to a national enthusiasm to obtain victory over the French – eventually achieved by Staunton in 1843 – but no date was attached to the club’s formation.

On page 1 of The Bristol Chess Club (Bristol, 1883) J. Burt claimed to have “undoubted evidence that it was formed in 1829 or 1830, under the Presidentship of Mr Elijah Williams”. Unfortunately, he did not mention what the “undoubted evidence” was. In 1836 the club and several of its members, including Williams and Withers, were listed among the subscribers on page 280 of William Greenwood Walker’s book A Selection of Games at Chess Actually Played in London by the Late Alexander M’Donnell, Esq.

The birth of his first daughter, noted above, shows that he had moved to London by the summer of 1846. Charles Tomlinson (BCM, February 1891, page 53) relates that “he gave up his practice for a precarious seat in the Divan”. If that was, in fact, his hare-brained plan, in official records, at least, he continued to be described as a surgeon for the rest of his life, and it was only in the 1851 census that “non-practising” was added.

His highest achievement was in the 1851 London tournament. After knocking out Löwenthal and Mucklow, he played a semi-final match against Marmaduke Wyvill. He took the first three games to stand on the verge of a place in the final, needing just one more win, but Wyvill, the MP for Richmond, Yorkshire, staged an extraordinary come-back and took the next four games. Williams’ peak had arrived and passed. Nevertheless, by his victory in the contest to decide third place he showed that he was capable of winning a match even against Staunton. The subsequent “revenge” match between them suggested that Staunton was then the stronger of the two, even though Williams won that second match too, on account of the three games’ start which Staunton had conceded. Brien, in his article, countered “a statement then published” to the effect that Staunton lost because of ill-health to an opponent “accustomed previously to take the pawn and two moves” by suggesting that in printed games Williams had not received those odds since 1845. However, he did not question Staunton’s “ill-health”.

A description of Williams’ mode of play comes from H.A. Kennedy in the above-mentioned article “A Desultory Ramble with the Chess-men” in Charles Tomlinson’s Chess Player’s Annual (London, 1856), page 47:

“Mr Williams is a player of large calibre. Tardy in unfolding his plans, and cautious in the extreme, he, nevertheless, marshals his forces with such ability and judgment, as to make them present a firm, compact front, within which no enemy finds it an easy matter to penetrate. His manoeuvres are conducted with soundness and precision, he has great accuracy of calculation, and his constant practice gives him a command of the board equalled by few.”

His two books were collections of games, Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club (Bristol, 1845) and Horæ Divanianæ (London, 1852). In the latter, his hostility towards Howard Staunton is amply reflected by the fact that Staunton was not mentioned anywhere in the book. Williams’ involvement with the Illustrated London Magazine was referred to in C.N. 9909. In addition, he contributed to the Bath and Cheltenham Gazette, The Field, and The Historic Times.

Slowness

Staunton blamed his defeat by Williams in the 1851 London tournament and in the return match on Williams’ excessively slow play. H.J.R. Murray, on page 84 of A Short History of Chess (Oxford, 1963), described him as ...

“the slowest of all players in a time of slow players (for chess clocks had not yet been thought of)”.

In The Times of 19 April 1980, page 7, H. Golombek remarked that Williams has ...

“good claims to be regarded as the slowest player in the history of the game”.

C.N. 3764 quoted some remarks by Irving Chernev about Williams’ supposed slowness. Chernev asked:

‘Was his prolonged thinking part of a plan to infuriate his opponents? Or was it because he was slowly evolving a new system of play?’

P.W. Sergeant alluded to “Williams’ exceedingly slow methods” on page 77 of A Century of British Chess (London, 1934). He made the point that Staunton had previously shown no “ill-feeling” towards Williams and suggested that the latter’s slow play was the sole cause. However, one could argue conversely that the cause was Staunton’s annoyance at being beaten.

In an advertisement for the Illustrated London Magazine the following appeared on page 6 of the Worcestershire Chronicle, of 13 September 1854:

“Mr Elijah Williams, the celebrated chessplayer, who wore out Staunton, contributes annotated games of chess and problems, which add to the former attractions of this pictorial.”

This text must have had Williams’ agreement, and one wonders exactly what was meant by the claim that he “wore out Staunton”. Does it go any way towards acknowledging slow play, or does it merely claim that Williams endured the exertion better? Or was it a joke?

In a letter to Bell’s Life in London, 7 December 1851, page 5, he explained that initially he said nothing ...

“as it was quite apparent to me that Mr Staunton was somewhat irritated by his defeat”.

Staunton’s irritability at that time is well known. In my book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton (pages 111-112) it was suggested that he was suffering from accumulative stress caused by the demands made on him by the 1851 tournament. C.N. 7858 describes an incident from the “return match” which reflects Staunton’s frustration or irritation, resulting in his making an unfair annotation.

Later, Williams felt the need to respond when Staunton persisted with his criticism, and he claimed that he “took no more time over his moves” than Staunton.

R.B. Brien, who had earlier been an ally of Staunton, indicated in his 1856 article that he found nothing remarkable about the speed of Williams’ play:

“The evidence, however, of those who witnessed several of his matches is to the effect that, although there might be an exceptional case, he was on the whole not so very slow.”

There was also support for Williams in the Chess Player, edited by Kling and Horwitz, volume two, 1852, page 304:

“As you observe, the unworthy efforts which have been made to fasten upon Mr Williams the stigma of wilfully playing a ‘slow march’, with the view of wearying out his antagonist, cannot be too strongly reprobated. We have had the good fortune to be present at some of the finest chess matches of late years, and we doubt very much whether Mr Williams’ play is any slower than that which we observed in the matches in question.”

Nevertheless, the number of contemporary players willing to defend Williams appears to have been limited. If he had suffered any real injustice from the criticism, would there not have been more sympathizers? After all, Staunton had no shortage of enemies during the period in question. No-one timed the players’ cogitations, as had Harry Wilson in the Staunton v Saint-Amant encounter in Paris, so uncertainty remains over how slow Williams was.’

11425. ‘Presumably’

‘Staunton showed the effectiveness of the English opening, 1 P-QB4. Actually, his greatest impact on chess history was a negative one: by refusing to go through with a match against Morphy, he presumably effected the latter’s disillusionment and permanent withdrawal from chess.’

Source: page 17 of The Battle of Chess Ideas by Anthony Saidy (London, 1972).

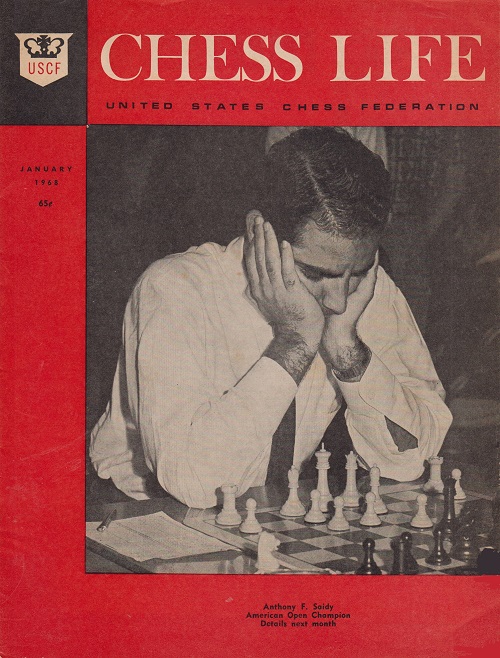

11426. Saidy on the front cover of Chess Life

From page 178 of the May 1969 Chess Life:

11427. An old joke

A Quotes and Queries item by D.J. Morgan on page 158 of the May 1970 BCM:

‘Overheard. “He is the Secretary of a Chess Club.” “But what does he do?” “He reads the hours of the last meeting.”’

A letter from Sanford V. Levinson on page 129 of the May 1955 Chess Review:

11428. When was Labourdonnais born?

Ulvi Bajarani (Baku) asks whether the exact year, let alone the exact day, of Labourdonnais’ birth can be established.

C.N. 4070 reproduced from page 202 of “Our Folder” (The Good Companion Chess Problem Club), 1 May 1921 a photograph of the master’s grave in London with a caption indicating that he died on 13 December 1840, aged 43. However, the obituary of Labourdonnais by Saint-Amant in Le Palamède stated:

‘Labourdonnais qui était né en 1795, l’année même de la mort de Philidor, a été comme lui mourir à Londres, dans un état voisin de la pauvreté.’

The obituary was on pages 15-19 of the first issue of Le Palamède following its resumption, circa December 1841, after more than a year’s absence. An endnote referred to prior publication of the obituary:

‘Cet article avait été publié dans les feuilles quotidiennes en février 1841, deux mois après la mort de Labourdonnais.’

The matter will be pursued in future items with, we hope, readers’ assistance.

11429. Paul Truong

From pages xviii-xix of Alpha Teach Yourself Chess in 24 Hours by Zsuzsa Polgar, Hoainhan “Paul” Truong and Leslie Alan Horvitz (Indianapolis, 2002/2003):

It is true as a matter of public record that South Vietnam fell in 1975.

| First column | << previous | Archives [180] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.