Edward Winter

The six books being considered were published during the four months or so following the match, the first of them (the Davies, Pein and Levitt volume) about two days after Fischer won game 30. Although no perfect correlation is detectable between the books’ merits and their order of publication, the best one was among the last to appear. (A seventh book in English, the 41-page Fischer-Spassky 1992, privately published by F.E. Condon in New Jersey, arrived much later than the others, and is anyway notable only for its cumbersome structure, with games presented by opening rather than chronologically.)

The 1992 Rematch by Jack Peters (a book henceforth called ‘Peters’) is the smallest of the works and the most modest in production values. The games are given with a smattering of information and gossip, other brief textual matter, and three photographs.

Fischer-Spassky 1992: World Chess Championship Rematch by Leonid Shamkovich and Jan R. Cartier (‘Shamkovich and Cartier’) has a roomy, single column format. All the previous Fischer-Spassky games are given, with very brief notes, followed by general background information, and then the 30 match games, each introduced by a page of quotes from chess personalities and others. The notes are clear and fairly detailed. Most games are followed by a set of ‘Supplemental Games’ with the same opening. The book, which has 19 contemporary, full-page photographs, ends with transcripts of the first two press conferences.

The Art of War Revisited – Robert J. Fischer vs. Boris V. Spassky 1992 by Mitchell R. White (‘White’) is oversized and unillustrated. It features 68 pages of unannotated ‘Supplementary Games’, a much more extensive selection than the comparable material in Shamkovich and Cartier.

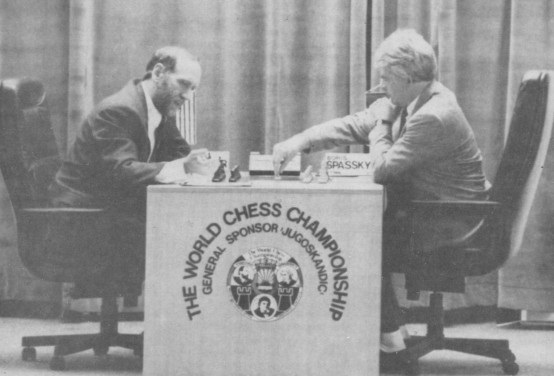

Bobby Fischer: The $5,000,000 Comeback by Nigel Davies, Malcolm Pein, and Jonathan Levitt (‘Davies et al.’) has 48 pages on Fischer, Spassky, and their rivalry, plus four pages of background on the match itself. Pages 53-125 give the 30 annotated games, and the book ends with notes about the Fischer clock and extracts from the first press conference. The only illustration is the cover photograph of Fischer and Spassky at the board.

Fischer-Spassky II: The Return of a Legend by Raymond Keene (‘Keene’) has brief background material, including the scores of earlier encounters, and then 99 pages on the 1992 games. Its only illustration is a caricature dating from the 1972 Reykjavik match on the front cover.

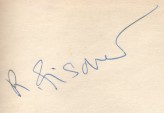

No Regrets by Yasser Seirawan and George Stefanovic (‘Seirawan and Stefanovic’) has 12 pages of introduction, 270 pages on the match games, 19 pages of Seirawan’s thoughts on Fischer, and a six-page glossary of terms and individuals. The middle section combines into a single sequence annotations, substantial background information, the text of all nine press conferences and the players’ post-game comments, and short interviews with over 30 leading figures, such as Anand, Botvinnik, Geller, Gligorić, Zsuzsa Polgár, Schmid, Short, Smyslov, Timman and Torre. Page 1 specifies that Stefanovic’s contribution was to write ‘the colour commentary for games 12-30’. The book has a dozen illustrations.

Some of the books have unwelcome frills. Keene, at the end of each game, moves the players’ Elo ratings up or down, but since the starting-point for Fischer is his 1972 rating and for Spassky his 1992 one, the exercise is of even less interest than the Shamkovich and Cartier computation of Fischer and Spassky’s ‘hourly pay to sit at board’.

Examining the game annotations offered by each book reveals immense variety. Consider game 30 as an example. Seirawan and Stefanovic give it some 190 lines of notes, about six times as many as Keene (32 lines), even though the latter claims to have concentrated on analysing decisive games. Of course, simple word counts may be misleading; White, for example, may take a paragraph where other writers would prefer a sentence or silence. There is also considerable difference of opinion on which moves should be criticized and praised.

The books generally avoid analytical dogmatism, but not all of them make use of the players’ own comments on the games. Although Spassky said at the concluding interview (quoted on page 272 of Seirawan and Stefanovic) that in game 30 his knight was bad on b3, only Shamkovich and Cartier speak against its move there, calling it ‘dubious’. After describing 13 g4 as ‘probably positionally a losing move’, Fischer pointed out 16...Ne5 17 h6, a line given only by Seirawan and Stefanovic.

Naturally there are contradictory views about the players’ overall performance. Peters (page 49) writes, regarding game 20: ‘Whenever it appeared that Fischer had regained his old form, he would throw in a game like this one. Inaccurate openings, inferior middlegame strategy, tactical oversights – how can a great player commit so many mistakes? Thanks to Fischer’s own chess clock, he cannot use time pressure as an excuse.’ But despite these severe words, Peters’ own annotations to game 20 criticize little in Fischer’s play. Davies et al. provide even less indication as to why Black lost the game.

None of the books gives the individual time taken for each move. Comment on Fischer’s clock is broadly favourable, with Davies et al. remarking that ‘It solves the problem of adjournments and desperate time trouble, but cannot remedy human exhaustion’ (page 103). According to Shamkovich and Cartier, ‘It will without a doubt eventually become the accepted method of timing chess games’, and pages 28-29 of their book also declare: ‘It is most significant that not one mention of time trouble has found its way into the coverage of the Fischer-Spassky 1992 match ... The new clock has great merit.’

The quality of language and general presentation varies greatly. Peters’ inconspicuous book affords little cause for complaint or enthusiasm. It opens with a two-page explanation of notation, yet by page 12 (in the notes to game 2) jargon is being used: ‘Black has an extra passer ...’ Many sentences in the sparse notes lack a finite verb, yet they retain a certain attractive dryness. The general textual matter tends to have a sharper edge; on pages 71-72 Peters says that ‘Two factors prevented this match from bringing unanimously favourable attention to chess. First was Fischer’s nasty temperament, as shown by his vicious accusations and conspiracy theories. Second was his decision to start his comeback in an outlaw nation.’

The back-cover blurb of the Shamkovich and Cartier book unconvincingly congratulates itself on being ‘THE complete account of the richest and most talked about match in the history of chess’. The book suffers generally from a poor prose style, and despite emphasis on proofreading in the publisher’s note, it has the most typographical errors, particularly in the closing pages. (The runner-up is probably White’s book, which is marred by a typographical defect whereby many foreign names have spaces instead of letters.) More than any other work, this one is engrossed by gossip, a sort of ‘hear and print’ style of journalism, as on page 107: ‘There are rumours circulating about future Fischer matches. One undocumented report claims that 19 million dollars has been raised for future matches by Fischer.’

The White book is larded less with rumours than with ruminations, e.g. sententious quotations from ancient Oriental philosophers such as Sun Tzu (‘Thus, what is of supreme importance is to attack the enemy’s strategy’ – page 15). Alongside is White’s own writing, a painful amalgam of coarseness and pretension. For example: ‘White has been forced to “pack ’em in” like sardines on the kingside’ (page 25), and ‘If this game included a studio soundtrack, then Black’s move would sound like a freight train hitting a buffalo’ (page 128). The chess pieces are often called ‘Cleric’, ‘Hopper’, ‘Button’, ‘Padre’, and ‘Cardinal’, etc. There is a juvenile over-use of exclamation marks, and when nothing is to be said, White is the man to say it. In Chess Life Ilya Gurevich wrote of a move in game 28, ‘If I did not know any better I would say that this game is fixed’. After quoting this, White (page 121) adds the following even more trite comment: ‘Eh? Fixed, you say ... Marvelous! Suffice it to say that young Master Gurevich’s impetuosity is no match for his perceptivity.’ White himself has a perceptivity and logic all of his own, as in his comment, ‘Spassky has never played this position before, and consequently blunders’ (page 109, emphasis added). Most of White’s annotations are notably dependent on the comments of others, and no other book has less background material.

The notes in Davies et al., which are by Malcolm Pein and Jonathan Levitt, are quite well written, and the authors concede that they do not always agree (as in game 12 on pages 90-94). A central contention of this book is that for Spassky ‘fighting Fischer on his 1960s and 1970s territory is a bad idea’ (page 82). Lack of time shows in the presentation of background material on Fischer and Spassky, which has a dishearteningly unimaginative selection of information and games. Once again the reader is served up Fischer’s brilliancy against Donald Byrne, who is pointlessly accused of playing on in a hopeless position: ‘perhaps he thought that by lengthening the game in this way he could make it less publishable’ (page 5). It is a pity, and this criticism applies to all but one of the works being reviewed, that so little use is made of the large quantity of Fischer facts available; apart from his writings, both known and neglected, over a period of more than 30 years, there are, after all, his extensive comments at the surprisingly frequent press conferences during the 1992 match. Davies, whom the introduction credits with writing the background sections, is nonetheless a sufficiently astute commentator to discern more in Fischer than the barren clichés of old. He suspects that ‘the rough exterior may conceal a man of warmth, sensitivity and integrity for whom the world has never been a very easy place to live’ (page 29). Not knowing for sure, Davies makes a virtue of simply acknowledging the problem: ‘It is certainly not easy to sift through the morass of rumour and speculation. Many of the stories have emanated from journalists looking to make a quick buck on a “crazy chess champ” article and happy to sacrifice accuracy to achieve the desired effect’ (page 25). He might have added that so-called specialized chess writers have been only slightly less guilty in this respect than journalists without a background in the game.

Next on the list is a book whose first introductory page (page 7) describes Fischer as ‘the greatest mind-warrior in the history of the planet’, whose last two pages (pages 129-130) call Fischer ‘the most extraordinary chess player ever to have walked the planet’, and whose final sentence says that a Kasparov-Fischer match will establish ‘who is the supreme mental gladiator on Planet Earth’. The prose is unmistakably that of Raymond Keene in full cry. Frantic overemphasis pervades Fischer-Spassky II: The Return of a Legend. Spassky’s king is not just cornered, it is ‘utterly cornered, with no hope of escape’; in other games Fischer has to ‘acquiesce in a completely hopeless endgame’ and Spassky’s ‘attacking prospects had utterly vanished’. Similarly, the background commentary comprises histrionics rather than history. In a typical example, the second paragraph of the Introduction (page 7) avers that the 1992 match ‘blasted the chess world, as well as those fascinated by the mind-bending eccentricity of the game’s most superb practioner [sic], into frenzies of excitement and anticipation’. Page 15 says that earlier games caused ‘unprecedented levels of anticipation and excitement’. But such flummery cannot disguise the author’s insufficient familiarity with Fischer’s life. On page 8 the reader is informed that Fischer ‘began to distribute scurrilous pamphlets whenever the opportunity arose’. Did he? When? What ‘opportunities’ arose? What were the scurrilities? How many such pamphlets has Keene himself seen? How many has anyone seen?

The slapdash prose, replete with misused vocabulary and grammar, cheapens whatever it touches. In game 25, as so often elsewhere, Keene has the bombast while others (Seirawan and Stefanovic in particular) have the analysis. At move 18, the Keene book has nine lines, beginning ‘Spassky has been so shell-shocked by 15 Nb6!! that he has been rendered witless and cannot gather his thoughts’. We learn that ‘Black must strike back quickly with either ...e5 or ...d5’, but no variations are offered. Seirawan and Stefanovic, in contrast, give several possible lines.

No Regrets is of outstanding quality, and probably even better than Seirawan’s monograph, highly praised by Fischer, on the last Kasparov-Karpov match. The annotations are magnificently detailed, and Seirawan is the only writer to cover Fischer’s declarations fully. He publishes the complete transcripts of all nine press conferences, whereas Shamkovich and Cartier give only two and Keene provides a summary of just the first, labelling it ‘The Press Conference’ as if the other eight never existed. Fischer’s insistence on selecting press conference questions stifled discussion, but the issues raised are of enthralling interest, even to historians. For example, Fischer said (as quoted on page 116 of Seirawan and Stefanovic), ‘Morphy, I think everyone agrees, was probably the greatest genius of them all ...’ His honesty is exemplified by the now-familiar quotation, ‘That’s chess, you know. One day you give a lesson, the next day your opponent gives you a lesson’ (page 52).

The transcripts in No Regrets highlight Fischer’s aversion to Kasparov, who is described as a ‘pathological liar’ (page 55) and ‘an outright crook’ (page 151). After stating that Kasparov wrote a letter to him signed ‘your co-champion’, Fischer remarked, ‘He is not my co-champion, he is a criminal and should be in jail’ (page 282). Having announced (page 212) that he will write a book to justify his allegations of prearranged world championship games, Fischer can hardly now do otherwise, but whatever supporting ‘proof’ he may have should in any case have been presented concurrently with the accusations.

The books, all written before the Kasparov-Short world championship controversy arose, show a surprising willingness to entertain Fischer’s claims to the world championship. Shamkovich and Cartier indicate (page 131) that Kasparov is ‘FIDE World Champion’, and their book has ‘World Chess Championship Rematch’ on the front cover and title page. Davies et al. too (page 23) call Kasparov the ‘reigning FIDE champion’, adding (page 24), ‘... Fischer’s anger at the three K’s becomes altogether reasonable when you start out from the premise that FIDE had no right to take Fischer’s title away’. Seirawan says (page 5), ‘To Fischer, Kasparov is merely FIDE champion. It is a compelling argument. Until the wondrous day when they play a match, the chess world has room for two World Champions’. On page 84 he adds, ‘I completely recognize and support Bobby Fischer as a World Champion. I also completely recognize and support Kasparov as FIDE Champion’. Nonetheless, on page 26 of his 1992 book Winning Chess Tactics Seirawan referred to ‘America’s former World Champion, Robert Fischer’.

The match books naturally accord Fischer far more esteem than do the media in general. One reason for Fischer’s bad press is his tendency to keep reporters off balance with statements which, without warning, switch from perspicacity to absurdity and back again. Cliché-loving journalists can be at ease in covering Fischer only if they ignore the perspicacity, emphasize the absurdity, and add a dose of invention. ‘A lot of these quotes about me are not correct’, protests Fischer on page 117 of Seirawan and Stefanovic’s book. Seirawan is doubtless right to say (page 290) that ‘Bobby is a pure person in the sense that he goes straight to the heart of a topic, no beating around the bush’. In other words, Fischer is neither diplomatic nor hypocritical, and, right or wrong, he has kept his beliefs and principles intact for 30 years. Kasparov has trouble not contradicting himself over what he said last Tuesday.

Among the ten authors, only Seirawan and Stefanovic went to the match. Seirawan spent time with the players, and his book is able to demolish numerous myths. On page 291, he writes, ‘After 23 September, I threw most of what I’d ever read about Bobby out of my head. Sheer garbage. Bobby is the most misunderstood, misquoted celebrity walking the face of the earth’. Hyperbole aside, it is hard to resist the force of this argument. We learn that Fischer is not camera shy (page 85), that ‘He smiles and laughs easily’ (page 96), and that ‘... Bobby is a wholly enjoyable conversationalist. A fine wit, he is a very funny man’ (page 303). On page 293 Brad Darrach’s savage book Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World is identified as the coup de grâce for Fischer’s reputation. He fought Darrach and his publishers in the courts and lost. It is regrettable that apart from some sketchy newspaper accounts, few details are available about Fischer’s litigation activities since the Reykjavik match. Peters claims (page 9) that ‘Fischer filed frivolous lawsuits, seeking tens of millions of dollars, then blamed the US government when they were thrown out of court’, but here, as elsewhere, the reader’s thirst for hard facts is not slaked.

The preface to No Regrets by the editor, Jonathan Berry, warns that readers will not find ‘a politically correct, blanket condemnation of Bobby Fischer’ but will be left to make up their own minds on the basis of the exhaustive accounts of Fischer’s views. Seirawan qualifies as an objective chronicler of Fischer, though he is certainly – to borrow from Tom Stoppard – ‘objective-for’ rather than ‘objective-against’. An important component that helps No Regrets to remain balanced is the series of mini-interviews with leading players; diametrically opposed views abound.

Seirawan and Stefanovic have produced the inside story, and their book’s superiority over the other five is such that even the best of them look shallow and almost irrelevant by comparison. No Regrets should serve as a model for future world championship match books, whoever the champion and challenger may be.

Afterword (written in 2005): This article was originally published on pages 115-121 of the second issue of the American Chess Journal, in 1993. It would be impossible today to write about Fischer the man in such terms. From the late 1990s onwards he gave a series of radio interviews in which, egged on by standardless ‘broadcasters’, he came out with the most abject set of utterances ever made by a chess master.

Below is the text of C.N. 1971, dated 9 May 1993:

On 7 January 1993 Yasser Seirawan gave a telephone interview (lasting nearly three hours) to Hanon Russell for the USA Today Sports Centre. Seirawan’s comments on Fischer, with whom he spent about 15 hours during the 1992 Spassky match, are of particular interest. Some extracts follow, slightly edited by us:

Fischer’s sense of humour:

‘Bobby has a very engaging smile. A friendly, friendly man and what really blew me away was how funny he was. We laughed for hours and hours. I mentioned to him Bruce Lee, and he said, “Bruce Lee! Did you see that movie?” And he gets up and mimics Bruce Lee and does this brilliant parody. Four people are on the floor just laughing, holding their tears back it was so good.’

One of the most surprising exchanges came when Seirawan offered Fischer the opportunity of using Inside Chess to express his views. Since Fischer had often accused people of misquoting him, Seirawan promised that he would not change a comma in anything Fischer submitted. An astonished Fischer stepped back and said, ‘You mean, I could have an editorial space? Well this ain’t a promise or anything like that, but I really want to thank you because no-one ever offered that to me before.’ Seirawan retorted that many publishers would be delighted to take anything Fischer wrote, and the latter replied, ‘Yeah, but they always change my words’. The conversation ended with Seirawan again assuring Fischer that not a word would be changed if he made a submission to Inside Chess, to which Fischer said, ‘Thank you. I will really think about it, but it is no guarantee’.

On Jews:

‘He explained to me that he was raised in a Jewish household, that he was basically abandoned by his father and that although he lived with his mother Regina, she went on to her education studies, left two children (his sister and him) at home, and he was very much abandoned as a child. I think that this terrible experience certainly affected him throughout his entire life. But he also explained to me that he was brought up in a chess community in Manhattan. He had to have a lot of savvy. There was an enormous number of Jewish people in the chess world, in New York, whom he communicated with on a constant day-to-day basis. Many helped him, and he acknowledges that. A little entry fee here, a book there, a ride there, etc. But he also says that many, many times he has had business affairs with Jewish businessmen which have not worked out. As a result of these experiences, his answer is “I don’t want to deal with Jews any more. That’s just the way it is. Yasser, I’m sorry, it’s a closed question”.’

When Seirawan argued that Fischer was ‘condemning a whole group of people’, Fischer replied: ‘Yasser, I know you think I’m being unfair. It’s just my experience. My reasons.’ Seirawan commented to the interviewer that Fischer ‘is a racist, he is not a Nazist’ and that he ‘magnifies his problems out of proportion. He takes his problems and puts them on the world stage’.

Fischer’s plans:

‘Bobby told me that his idea was to play three matches in 1993 and whip Kasparov in 1994. His intention was to play three top players. He specifically singled out the loser of the Timman-Short match. He further mentioned specifically Michael Adams of England and Viswanathan Anand of India. He doesn’t want to play me. He doesn’t want to play any American because he feels that he doesn’t have an American challenger.’

A comment of ours in Instant Fischer (‘Kasparov has trouble not contradicting himself over what he said last Tuesday’) was quoted by Olimpiu G. Urcan on Twitter on 23 February 2021, accompanied by a clip from the 1937 Laurel and Hardy film Way Out West in which, replying to ‘What did he die of?’, Stan Laurel said, ‘I think he died of a Tuesday ...’ A question of language arises: why, in such cases, is Tuesday the most effective day to mention?

We have put the matter to Stephen Fry, who replies:

‘No question that Tuesday is the funniest day. Always has been. Though Douglas Adams came up with that line “This must be Thursday. I never could get the hang of Thursdays” which shows Thursday comes in a good second. Monday wouldn’t work because there’s a reason why “I don’t like Mondays” as Bob Geldof sang. Wednesday is just too much of a mouthful to zing. Friday is too associated with payday and the end of the week, and the other two days are reserved for weekend properties. So perhaps it’s more a process of elimination … I wonder if any continental languages have equivalents. Is Mittwoch as funny as Dienstag?

Tuesday doesn’t follow the “hard C” rule (see the film The Sunshine Boys for a wonderful scene involving hard Cs).

Noël Coward often pondered why some place names are funny, and even claimed that in America funny place names are only funny because the word itself is inherently amusing “Schenectady” “Kalamazoo” “Albuquerque" – whereas the British find certain places funny for less obvious reasons: “Neasden" and “Purley” might elicit a laugh, whereas “Hendon” and “Portsmouth” for example wouldn’t. Hugh [Laurie] and I got much mileage out of Uttoxeter, mileage that Exeter or Huddersfield would never have offered …’

(11857)

See too Articles about Bobby Fischer, Spassky v Fischer, Reykjavik, 1972, Boris Spassky and Yasser Seirawan.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.