Edward Winter

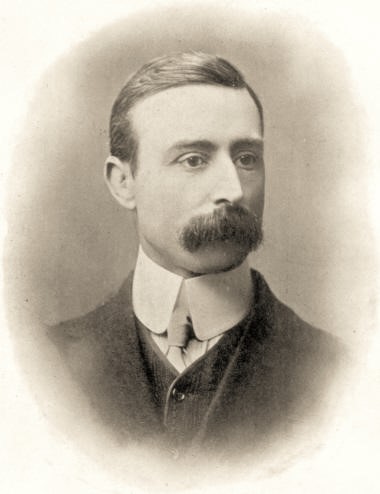

We bring together a series of C.N. items about Harold James Ruthven Murray (1868-1955).

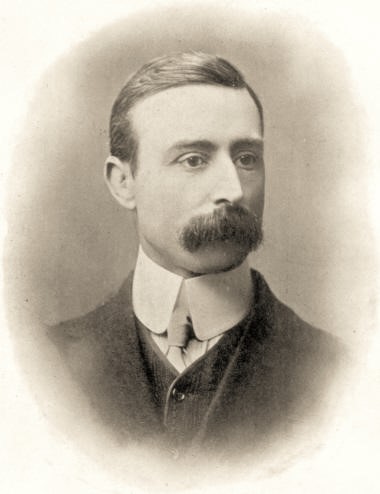

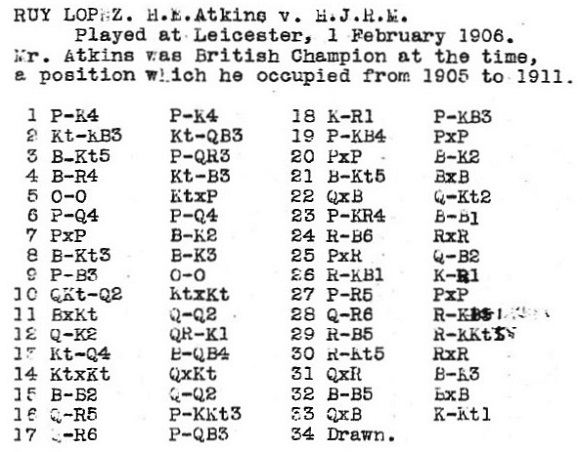

From page 124 of the April 1916 BCM:

This is still the only chess game played by Murray that we have seen.

Shortly before his death, H.J.R. Murray wrote:

‘The days when my copies of Chess World arrive are red letter days. I still think it the best of all chess magazines and revel in every word of it.’

Source: Chess World, May 1955, page 98.

(2490)

Such was the scholarship of H.J.R. Murray that assumptions have been made that he was more than plain ‘Mr Murray’. On page viii of Fiske’s posthumous Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature (Florence, 1905) Horatio S. White referred to ‘an eminent English authority on chess, Dr Harold J.R. Murray’. Then there is ‘Professor Murray’ on page 7 of The Literature of Chess by John Graham (Jefferson, 1984).

As recorded in the obituary by D.J. Morgan on pages 233-234 of the August 1955 BCM, Murray ‘took an Open Mathematical Exhibition to Balliol College, Oxford, and left the University, in 1890, with a First Class in the Final Mathematical School’. Balliol College Library has confirmed to us that these details are accurate and that no evidence exists that Murray had a doctorate. In 1891 he began a career in teaching, as Assistant Master at Queen’s College, Taunton.

The obituary by D.J. Morgan called Murray’s 1913 book A History of Chess ‘an enduring monument, the greatest book ever written on the game’. In an appreciation on page 114 of the September-October 1944 American Chess Bulletin Ernest J. Clarke wrote, ‘Unfortunately, I find that the History is considered ‘dry’ reading; on the contrary, it is so fascinating it is difficult to put it down’. On page 189 of The Kings of Chess (London, 1985) William Hartston described it as ‘The classic book on the subject; 900 pages of meticulous research, practically unreadable’. In his Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977) Harry Golombek wrote (page 355) that the book bore witness to Murray’s learning and industry, before adding obliquely: ‘It suffers however from the lack of a sense of history’.

Egbert Meissenburg presented a bibliography of Murray’s books and articles on pages 249-252 of the May 1980 BCM. Two omissions were pointed out by P. Bidev on page 107 of the March 1981 BCM, but there was still no mention of what seems to be Murray’s final published article, a review of J. Boyer’s Les jeux d’échecs non orthodoxes on page 75 of the March 1952 BCM. By then Murray was in his mid-eighties, and it was nearly four decades since his History had appeared. Thus F. Reinfeld was incorrect to state on page 5 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963) that Murray ‘devoted a lifetime to a monumental history of chess’.

H.J.R. Murray (La scacchiera, June 1953, page 130)

(3212)

Another writer who incorrectly attributed to H.J.R. Murray an academic title was Alfred C. Klahre, during his discussion of the Rou manuscript on page 13 of the January 1933 American Chess Bulletin (‘in a letter to the writer by Prof. H.J.R. Murray, Oxford, England’).

(3314)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) notes the reference to ‘Professor H.J.R. Murray’ on page 216 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951), in an article by C.J.S. Purdy ‘Thirteen Centuries of Chess’, originally published in Check!, 1945. The article ends (pages 231-233 of Reinfeld’s book) with a letter from Murray to Purdy.

C.N. 10865 quoted from the cover page iii of CHESS, May 1973: ‘Professor H.J.R. Murray’.

‘Professor H.J.R. Murray’ was mentioned on page 215 of the April 1927 Chess Amateur.

Any readers who are loath to tackle H.J.R. Murray’s 900-page A History of Chess (Oxford, 1913), or even to read his posthumous volume A Short History of Chess (Oxford, 1963, but written in 1917), may be interested and grateful to know that, a year before his death, he published an article on the origins of chess which was only 1,500 words long. It appeared on pages 88-90 of Things (London, 1954), a general reference book published by the Waverley Book Company Limited, and is reproduced below.

‘Chess is too well known to require a detailed description – enough to say that this greatest and most intellectually elegant of games of skill is played by two persons on a board of eight by eight “squares”, each player having 16 “men” – king, queen, two bishops, two knights, two rooks or castles and eight pawns, each type of man with its own powers of move and capture, the object of the game being to checkmate the adversary’s king – to force him, that is to say, into a position from which he cannot move without capture. Chess was invented in India, and before Indian chronology was put on a sound basis, exaggerated ideas as to the age of chess were formed and these are still often repeated.

It is in Indian and Persian works of the first half of the seventh century A.D. that chess is first mentioned; and of these works the oldest is the Karnamak, a Persian romance in which the hero is said to have excelled all his contemporaries at chess (chatrang). This was written about A.D. 600. Somewhat later chess is mentioned by Bāna, in his Sanskrit Harshacharita, in which he describes the peace and good order of Northern India under Sriharsha (A.D. 612-647), in a passage full of puns: “under this king only bees (shatpada) quarrel in collecting dews (dues), the only feet cut off are those in metre, only chess boards (ashtapada) teach the positions of the chaturanga (army or chess).” The ashtapada was a board of eight by eight squares which had reached India from Greece in the first millennium B.C., Greece and India having been in contact at least from the time of Alexander the Great.

The older Arab historians agree that chess was an Indian invention which reached Persia in the reign of Chosroes I (A.D. 531-579), and this is generally accepted as true. The invention of chess cannot be placed much earlier, for from A.D. 458 to 540 Northern India lay under the cruel domination of Hun hordes from Central Asia which “shook Indian society to its roots and severed the chain of tradition”. The invention of chess is accordingly dated about A.D. 560. This leaves rather a brief period for the adoption of chess in Persia, a difficulty that can be met by the facts that Chosroes aided in the destruction of the Huns, and that his interest in Indian culture led to his sending envoys to India to obtain a copy of the Fables of Pilpay. Later Arab historians ascribed the inception of chess to an Indian sage they called Sissa b. Dahir, borrowing the name which belonged to the first Indian prince with whom the Arabs came in contact. In fact the story is mythical.

That the inventor’s idea was to make a game of skill in which the operations of an Indian army could be illustrated is evident from the names which he gave to the game and its “men”. The complete Indian army from at least the fourth century B.C. contained four kinds of troops, infantry, cavalry, chariots and elephants, the aggregate being called a chaturanga, “composed of four elements”. In his game of chaturanga, the inventor added to these four elements the king and his minister or commanding officer; and he arranged his armies on the two opposite outer rows of the ashtapada, placing one army on the first and second and the other on the seventh and eighth rows; on the second and seventh rows he placed eight pawns, and on the first and eighth rows, starting from the corners of the board, he placed chariot, horse and elephant; on the two middle squares he placed king and minister, the two kings standing on the same file. He gave the king a move of one step in any direction, the minister one step diagonally; to the chariot he gave the move which the rook has in our modern chess, and to the horse the leap of the modern knight. The elephant leapt diagonally over one square to the square immediately beyond. The pawn took single steps forward on the file on which it stands, made captures on an adjacent square diagonally in advance, and was promoted to the rank of minister on reaching the end of the board. The aim of the game was either to checkmate the opponent’s king or to deprive him of all his men. Stalemate, which has no analogy in actual warfare, he gave as a win to the stalemated king.

The Persians only made two changes in the Indian game. They translated the names of the men and they made stalemate a draw. The Arabs when they conquered Persia, in A.D. 638-651, made no alteration in the Persian rules. Pre-Islamic Persia knew the game for less than a hundred years, but this brief period had an effect of great importance upon chess, since it gained a fixity of arrangement, a method of play, and a nomenclature which have attended the game everywhere in its western career.

Islam absorbed chess quickly and the names of many chessplayers before 750 have been preserved. Wherever Islam penetrated, so did chess, as far west as Spain, as far south as Zanzibar, as far east as the Malay Islands and as far north as Turkestan. But lawyers maintained that playing chess was against tradition and the Koran. The matter was only settled for the Sunnite sect by ash-Shafi‘i (d. 820), who was himself a chessplayer skilled in blindfold play, on the ground that chess was not only a game but a training in military tactics (it is part of the modern training of Russian army officers); he held that chess was lawful provided it was played with conventional men, was not played for money or in public, and did not interfere with the performance of religious duties. The Shiite sect omits the first condition. These rules never troubled the caliphs, who played freely and patronized good players, watching what we should call “championship contests”. Players were classified by their skill, and the names of the chess champions from 800 to 950 are known. Two of these, al-‘Adli and as-Sūli, wrote books on chess which are still quoted, and al-Lajlāj, a pupil of as-Sūli, enunciated the principles of play.

Christians on the Spanish Marches were playing chess soon after A.D. 1000, and it was played in Italy not much later. By 1100 it was played in Bavaria, France and England, and by 1250 it had reached Iceland. English and French players adopted the eastern names when they did not understand the meaning, and translated them when they did. Thus in England the minister became a “fers” (Arabic firzān, Persian Ferzēn, “wise man”, “counsellor”), the elephant an “alfin” (Arabic al-fīl, “the elephant”), and the chariot a “rook” (from the Persian rukh, for “chariot”). Our “checkmate” is from the Arabic shāh māta, “the king is helpless”, “Chess”, too, came into English in the Middle Ages and goes back through Arabic and Persian to the Sanskrit chaturanga. “Pawn” comes from a medieval French word for a foot-soldier. The Italians made chess a model of the European state, the minister becoming a queen and the elephant an elder who was often carved as a bishop. When the Lombards acquired the reputation of being the best European chessplayers, these changes of name were adopted in France and England. Chess became immensely popular, first in royal and knightly circles, then in towns and finally and more sparsely with the commonalty. By 1250 the earlier prejudice of the Church against chess was weakening, since the game was patronized by kings, and the monastic orders were gladly accepting chess as an alleviation of the monotony of convent life. By 1300 chess had acquired a literature of its own, had become the theme of poems, sermons and moralities, and was influencing the plot of romances. Chess had also become a regular feature in the education of royal and noble children.

Despite the general popularity of chess, there were signs that players were a little disappointed with it: a game took too long. Giraldus Cambrensis towards the end of the twelfth century noted that English players were dropping chess and turning to the solution of chess problems in which fewer men were used and which had a prescribed length. On the other hand, in Italy, the Lombard players were strengthening the moving power of some of the men, and by 1300 had given queen, pawn and king, in this order and for their first move only, an additional power. These attempts culminated in the great reform of the 1490s which gave queen and bishop their modern moves, making the study of Opening Play both possible and necessary, and revivified chess altogether. These changes led to the great chess activity of the period 1550-1640 in Italy and Spain, during which the reform was completed by the addition of “castling”, the combined move of king and rook. The reformed game was then adopted in Europe generally.’

(3642)

Chess, The History of a Game by Richard Eales (Batsford) is a concise, well-written summary of current knowledge, though not really the work of outstanding original research promised by the blurb. The early chapters are particularly well handled, while we detected a certain thinness in the coverage of the period circa 1850-1950, accentuated by the fact that the author is considerably stronger when writing about trends than about individuals.

Although general comments on Murray are complimentary, H.J.R.M. is frequently criticized on specifics. Golombek’s 1976 history, beautifully produced but marred by the author’s own over-obtrusive personality, is not given very much acknowledgement.

Eales is careful about his facts, although we did note the following: misspelling ‘MacDonnell’ (e.g. page 132); page 153, Lasker did not become a doctor in 1902; page 153, Lasker played four, not three, tournaments in the period under consideration. Page 161: Marshall did not become US Champion in 1906. Page 194: FIDE’s motto is misspelled.

In addition there are many statements which are, at the minimum, debatable, while certain historical references, such as the Glasgow Herald one on page 156, arouse suspicions about Eales’ well-rounded knowledge of the game’s history.

In general, though, a carefully prepared book, the hallmarks of which are clarity and common sense.

(878)

Concerning world champions’ knowledge of chess history Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) notes the passages in Chess Facts and Fables regarding Kasparov (pages 237-241) and Lasker (pages 248-249) and draws attention to Capablanca’s remarks on pages 15-16 of Last Lectures (New York, 1966):

‘A great deal has been said and written about the origin and history of chess. An excellent work on this subject is that of the Englishman H.J.R. Murray, published by the Oxford Press in 1913. This writer claims that the type of chess we play originated in India relatively recently (about A.D. 700) and that it is derived from an earlier game. This work, entitled A History of Chess, contains many interesting facts and can be recommended to all who are interested in learning more about the fascinating history of the game of chess.

Mr Murray’s conclusions seem to me of rather doubtful value. Shortly before the beginning of the present war, for example, the New York Times published an item telling about excavations in Mesopotamia during the course of which there had been found objects proving that chess had existed at least as far back as 4000 B.C. It seems likely that chess, or a similar game, has been played for so long a time that to fix its origin and antiquity is impossible.

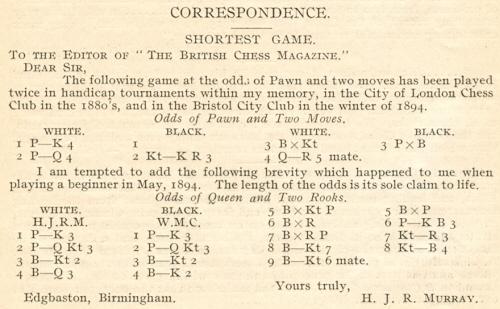

In 1937 a lavishly illustrated book was published in New York which dealt with the origin and history of famous collections of chessmen of all epochs. This volume contains many interesting facts; and yet, who can say how many sets have disappeared which were older than the oldest sets mentioned in this work? My own experience is enough to demonstrate with what ease one loses chess sets.’

A footnote on page 16 of Last Lectures identified the New York book as ‘A History of Chessmen by Donald M. Liddell and G.A. Pfeiffer’, but for the correct details see the title-page below:

Is a reader able to hunt out the New York Times report referred to by Capablanca?

(4806)

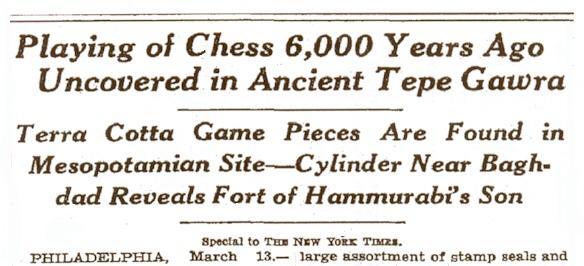

C.N. 4806 asked for details about a New York Times report on archaeological discoveries referred to by Capablanca in Last Lectures, and the full item has now been supplied by Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA), from page 17 of the newspaper’s 14 March 1938 edition:

The report was based on ‘evidence announced today by the University of Pennsylvania Museum and the American School of Oriental Research in Baghdad’. It stated that ‘on the 14th level of the site of the ancient Tepe Gawra, in Northern Iraq, members of a joint expedition of the two institutions have found a collection of small terra cotta gaming pieces which, they said, were shaped like human figures and resembled closely some of the chessmen used in various stages of the game’s development’.

A little more from the newspaper’s report is quoted below:

‘Dr E.A. Speiser, director of the Baghdad school and Professor of Semitics at the University of Pennsylvania, who found the Tepe Gawra site in 1927, said that these finds offered the first indication that chess, or its prototype, was a diversion of the prehistoric Mesopotamians of about 4000 B.C.

... The gaming pieces discovered by the present expedition show evidence of considerable use. The level on which they were picked up belongs to the El-Obeid period of the earliest known settlements in Southern Mesopotamia.

This season’s expedition, led by Charles Bache, assisted by John J. Tobler, has had to do with the Samarra and Obeid painted pottery periods.’

(4810)

Page 200 of Chess Facts and Fables quoted some opinions on Murray’s A History of Chess which ranged from ‘practically unreadable’ (W.R. Hartston) to ‘so fascinating it is difficult to put it down’ (E.J. Clarke). The latter view may seem eccentric but is in accord with a comment by CHESS on, for instance, the back cover of its June 1944 issue:

‘A colossal work, accepted as authoritative and exhaustive – yet it grips like an adventure story.’

Page 516 of the December 1912 BCM announced the forthcoming appearance of Murray’s book ‘upon which he has been engaged for more than 13 years’.

(4893)

The following improbable addition comes from page 286 of CHESS, 29 June 1963:

‘It was said of Murray’s History that it grips like a novel.’

(5971)

C.N. 4005, an item entitled ‘Pre-chess chess quotes’, gave the following from page 5 of Chess Quotations from the Masters by H. Hunvald (Mount Vernon, 1972):

‘When you are lonely, when you feel yourself an alien in the world, play chess. This will raise your spirits and be your counselor in war. – Aristotle.’

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) draws attention to this passage on page 219 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913):

‘From the time of al-Ma’mūn onwards, the writings of the more famous Greek philosophers became known to the Muslim world in translation. It was, perhaps, inevitable that the scattered allusions to the Greek board-games which occur in Plato and other writers should be misapplied to chess, but to this we owe the statements in H and later chess books that Aristotle, Galen and Hippocrates were also chessplayers.’

Page 175 gave the meaning of ‘H’: ‘MS John Rylands Library, Manchester, Arab. 59.’

A further extract from Murray’s book (page 164):

‘Greek literature and tradition are alike silent as to the existence or otherwise of these works and theories, and when we turn to the Arabic chess MSS which are based upon the works of al-‘Adlī and aṣ-Ṣūlī, we find the only references to Greek chess relate to the philosophers Hippocrates and Galen, and to Aristotle.’

(5655)

‘If we were to accept the statements of translators we should believe that Adam and Eve, Solomon, the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, the inhabitants of America before the time of Columbus, all played chess. When a translator finds a game mentioned in the text he is translating, he naturally replaces its name by the name of a game which is familiar to his readers and which enjoys a like reputation. The serious historian has to go behind the translation to the original texts.’

Source: a letter from H.J.R. Murray headed ‘Chess in Ireland’ on pages 503-504 of the December 1933 BCM.

(11227)

See also Pre-Chess Chess Quotes.

From Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA):

‘On page 287 of Means Davis’s novel The Chess Murders (New York, 1937) a character remarked regarding H.J.R. Murray’s work: “I wouldn’t take that book too seriously”.

Davis also introduced two chessic phrases which never caught on: “playing chess on it” (page 263), i.e. thinking about a problem as a chessplayer thinks about a position, and “it wouldn’t be chess” (pages 300-301), i.e. it would not be fair or admit a logical response.’

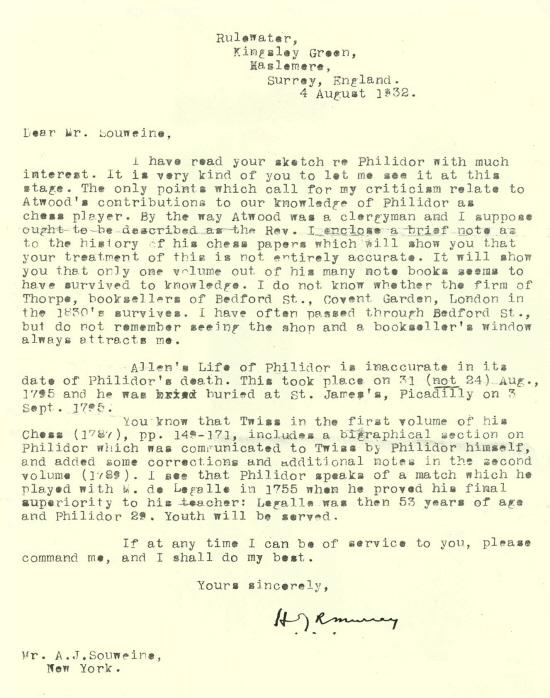

Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) has sent us a copy of a letter dated 4 August 1932 from H.J.R. Murray to A.J. Souweine:

(6000)

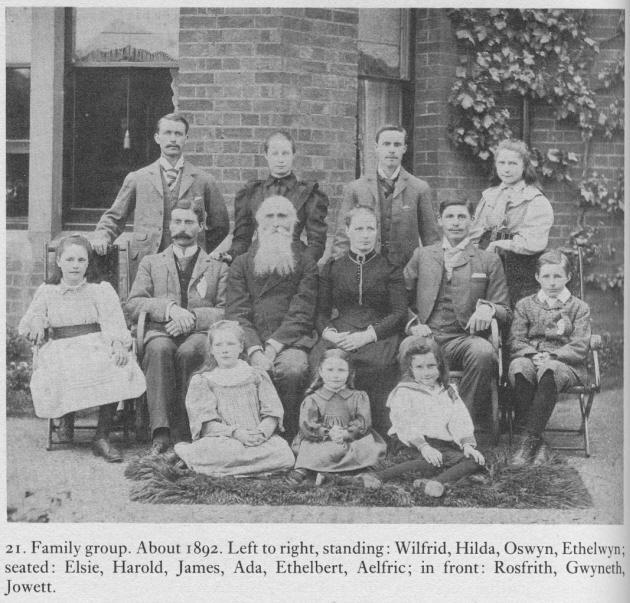

Christopher Lenard (Bendigo, Victoria, Australia) reports that the biography of James A.H. Murray Caught in the Web of Words by K.M. Elisabeth Murray (Oxford, 1977) has on page 316 a photograph which includes H.J.R. Murray (her father):

(6169)

E.B. Osborn’s review of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray on pages 1 and 2 of the Times Literary Supplement, 23 October 1913 exemplifies how new books were often scrutinized in a long lost age.

(9438)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

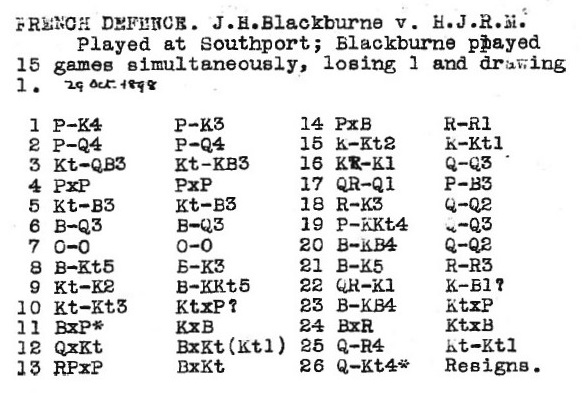

‘The Bodleian Library, Oxford holds the H.J.R. Murray Papers (MSS H.J. Murray 1-168), donated to the library in 1955, the year of Murray’s death. This valuable archival material includes a document by Murray which gives details of his chessplaying activities (MS H.J. Murray 73, folios 210-292). It comprises a five-page introduction by Murray and 95 of his games, played between 1893 and 1937. Most were against club-level amateurs, but he also had encounters with Blackburne and Atkins.’

Our correspondent plans to present a large selection of the games on his Patreon webpage (C.N. 10866) but has given us the two above-mentioned scores:

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 exd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 Bd3 Bd6 7 O-O O-O 8 Bg5 Be6 9 Ne2 Bg4 10 Ng3

10...Nxd4 11 Bxh7+ Kxh7 12 Qxd4 Bxg3 13 hxg3 Bxf3 14 gxf3 Rh8 15 Kg2 Kg8 16 Rfe1 Qd6 17 Rad1 c6 18 Re3 Qd7 19 g4 Qd6 20 Bf4 Qd7 21 Be5 Rh6 22 Rde1 Kf8 23 Bf4 Nxg4 24 Bxh6 Nxh6 25 Qh4 Ng8 26 Qb4+ Resigns.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 d5 7 dxe5 Be7 8 Bb3 Be6 9 c3 O-O 10 Nbd2 Nxd2 11 Bxd2 Qd7 12 Qe2 Rae8 13 Nd4 Bc5 14 Nxc6 Qxc6 15 Bc2 Qd7 16 Qh5 g6 17 Qh6 c6 18 Kh1 f6

19 f4 fxe5 20 fxe5 Be7 21 Bg5 Bxg5 22 Qxg5 Qg7 23 h4 Bc8 24 Rf6 Rxf6 25 exf6 Qf7 26 Rf1 Kh8 27 h5 gxh5 28 Qh6 Rg8 29 Rf5 Rg4 30 Rg5 Rxg5 31 Qxg5 Be6 32 Bf5 Bxf5 33 Qxf5 Kg8 Drawn.

(10874)

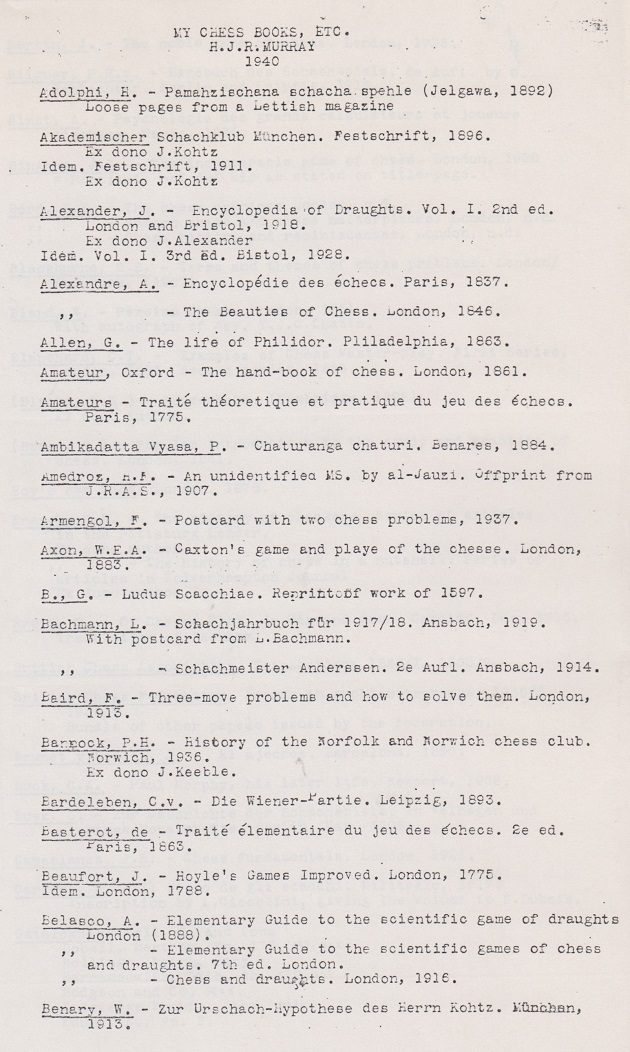

We have a copy of a 19-page typescript by H.J.R. Murray dated 1940, ‘My Chess Books, etc.’:

For a letter from Murray published on pages 135-136 of the June 1942 BCM, see our article on C.E.M. Joad, Chess: Prodigies, Philosophy and Mathematics.

C.N. 3212 quoted William Hartston’s exact words about A History of Chess, on page 189 of The Kings of Chess (London, 1985):

‘The classic book on the subject; 900 pages of meticulous research, practically unreadable.’

(12104)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.