Edward Winter

(1998, with additions)

Readers are given an opportunity to test their analytical skills against some of the greats of the past; Steinitz and Capablanca are among the luminaries who experienced difficulty in solving the positions below.

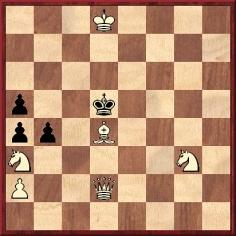

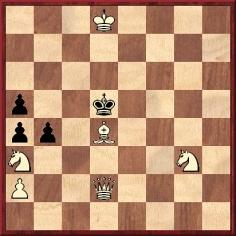

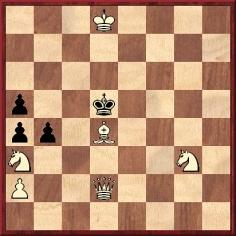

ONE:

Mate in three. (Morphy ‘took over an hour’.)

TWO:

Mate in four. (Steinitz and Loyd thought the diagram must be incorrect, but it is not.)

THREE:

Mate in four. (Steinitz failed to find the complete mating line.)

FOUR:

Mate in two. (Steinitz admitted taking over 15 minutes to solve this one.)

FIVE:

Mate in two. (Capablanca gave the wrong key move.)

SIX:

Mate in three. (Capablanca thought that there was no solution.)

SEVEN:

Mate in two. (The composer claimed that this was one of the hardest two-move problems extant.)

EIGHT:

Mate in three. (Another position that some wrongly considered unsolvable.)

Now the solutions and some background information.

ONE:

Mate in three

Key move: 1 Qd1.

This problem was given in the book on Alekhine by the late Pablo Morán (page 31 of the Spanish original and page 17 of the English edition) with a report that at Gijón in 1945 Alekhine solved it immediately, whereas Morphy had taken over an hour.

In 1989 we asked Morán about his source for the Morphy story, and he kindly provided a copy of pages 463 and 479 of Traité élémentaire du jeu des échecs by Count de Basterot (Paris, 1863), in which the Count related that he had witnessed Morphy’s long think. For the composer’s name he used the spelling ‘Wassman’ and Morán put ‘Washman’, but the problemist in question was probably D. Wasmann (1817-80). Alekhine expressed understandable surprise that the composition had detained Morphy so long.

TWO:

Mate in four

Both Steinitz and Loyd had great difficulty with this composition by Johannes Obermann, published on page 254 of the August 1885 Deutsche Schachzeitung. It was reproduced by Steinitz on page 320 of the October 1885 issue of the International Chess Magazine with the following introduction:

‘We reprint this problem as given in the Deutsche Schachzeitung, though we have not been able to find the solution yet. Mr Loyd, who has also failed to solve this problem, suggests that a black pawn at Black’s QKt5 [i.e. b4] should be added on…’

Page 349 of the November 1885 issue reported that Loyd had seen the problem published without a black pawn at c5 and that either amendment (i.e. an extra black pawn at b4 or no black pawn at c5) would allow the following solution: 1 Qf7 Nxf6 2 g7 Kd4 3 Qg6 and mate next move. Other second moves by Black would permit 3 Qg6+. If 1…Rxf8 2 Nc3+ Kd4 3 Qd5+ and mate next move. If 1…Kd4 2 Rf4+ e4 3 Qf5 and mate next move. After any alternative first move by Black, mate is administered by 2 Rf4+ exf4 3 Qxf4 mate. (Our computer shows that without a black pawn at c5 1 Nc3+ would also mate in four.)

In fact, though, the problem required no amendment. Obermann gave the solution as follows (see the International Chess Magazine, December 1885, page 379, and Deutsche Schachzeitung, March 1886, page 71):

1 Bd8 Rxd8 (or 1…Rb7) 2 Ne6 Nxf6 3 Q(x)b7 Kf5 4 Ne7 mate. Any other third move by Black would allow 4 Bd3 mate.

If 2…Nf8 3 Ng5+ Kd4 4 Rf4 mate. If at move two the black knight moves elsewhere or the rook moves, then 3 Bd3+ and mate next move. On other second moves by Black, 3 Ng5+ and mate next move.

Finally, 1…Nxf8 2 Qxf8 Kd4 3 Rf4+ exf4 4 Qxf4 mate.

Three years later, Obermann was dead, aged only 31. On page 272 of the September 1888 number of his magazine Steinitz called the above problem ‘one of the most difficult four-movers we have ever seen’.

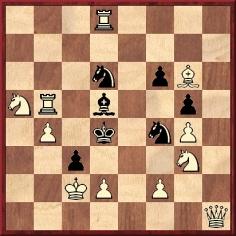

THREE:

Steinitz and Loyd clashed over a problem by the latter which Steinitz could not solve correctly in all particulars. It is the ‘Stuck Steinitz’ position, originally published in Mirror of American Sports, 10 October 1885:

Mate in four

Loyd made a bet with Steinitz that he would fail to find the correct solution, but after half-an-hour Steinitz declared that he had solved it, as follows: 1 f4 any 2 Bf8 any 3 Bxg7 any 4 Bxf6 mate. Loyd then pointed out the defence 1…Bh1 2 Bf8 g2, after which 3 Bxg7 would be stalemate. The solution, therefore, was 2 b3 g6 3 Be7. Loyd suggested that the problem should be published ‘under the motto “S.S.” – Stuck Steinitz’.

Source: Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913), pages 87, 450 and 451.

However, our computer check shows that after 1 f4 Bh1 there is an alternative to 2 b3: 2 Bb8, followed by 3 Bxa7 and 4 Bxb6 mate (or 3 b3 in reply to 2…g5).

To complicate matters further, a book on Sam Loyd, The Puzzle King edited by Sid Pickard (Dallas, 1996), puts forward (page 197) a different position under the heading ‘Steinitz stuck’:

Mate in four

The solution given is 1 Bd6 Bh1 2 b3 g6 3 Be7 g2 4 Bxf6. (A second possibility is 1 Bc7.)

The book also attributes this position to Mirror of American Sports of 1885 and wrongly classifies it as an impossible position. (The bishop on b8 could have resulted from promotion.)

Steinitz also referred to this problem in a letter to W. Shinkman dated 29 September 1889. See pages 111-112 of The Steinitz Papers by K. Landsberger (Jefferson, 2002).

Note: The above account contains a correction of a date on page 10 of A Chess Omnibus because subsequently, in C.N. 3458, John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) reported that the original publication was in Mirror of American Sports of 10 October 1885 (and not ‘November 1885’, as stated by A.C. White’s book and followed by us). Dr Hilbert also noted that the solution appeared in the 28 November 1885 issue (mentioning the 2 Bb8 dual continuation). What has not yet been found is a contemporary source for the different version of the composition given by S. Pickard.

FOUR:

Mate in two

The key move to this problem by Walter Pulitzer is 1 Qf6. Page 60 of Lasker’s journal the Chess Player’s Scrap Book, April 1907 quoted Steinitz’s view:

‘The problem is sound, original, difficult and beautifully constructed. Altogether a gem! So far as I can remember, this is the first time (probably in 35 years) that I have failed to solve a two-move problem within 15 minutes.’

FIVE:

Now the first of two problems which caught Capablanca. It is by P.K. Kuiper:

Mate in two

Key: 1 Kg5. Capablanca put forward 1 Qg7, which is met by 1…cxb4.

Source: BCM, April 1917, page 126.

SIX:

Mate in three

As reported on page 236 of the November 1916 American Chess Bulletin, Capablanca considered that there was no solution to this problem by T.C. Henriksen (which had been published on page 213 of the December 1915 Tidskrift för Schack).

Key move: 1 Rb7 (Threatening 2 Rc7+ Bc6 3 Nd5 mate. If 1…Bxb7 then 2 Qc8+, etc. and if 1…Ne6 then 2 Qa8.)

C.N. 1690 quoted the following from page 236 of the November 1916 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Mr Capablanca will good-naturedly admit having reported that Problem No. 1,114 apparently could not be solved as printed in the Bulletin, for we have received a blue-penciled replica of our diagram, from headquarters, bearing the statement that the famous Cuban had voiced his misgivings, we being invited to confirm the position, which same, as a matter of fact, was correctly printed and perfectly solvable. Consequently, trusting that the above item, written en passant, will be received in the spirit in which written, we proceed to christen T.C. Henriksen’s three-mover “Caught Capablanca” ...’

For details regarding an earlier (1915) problem-solving display by Capablanca see page 89 of our book on the Cuban and pages 378-379 of Walter Penn Shipley by John Hilbert (Jefferson, 2003).

SEVEN:

‘One of the most difficult two-move compositions extant’ was Napoleon Marache’s description of this problem of his, which appeared on page 121 of Marache’s Manual of Chess (New York, 1866):

Mate in two

Key: 1 Bf7. An interesting problem with a Zugzwang theme.

EIGHT:

Mate in three

Key move: 1 Qg2. The line 1…Kf6 2 Qh1 is particularly attractive. Another problem involving Zugzwang.

‘We call especial attention to this problem; it is one of the very finest extant’ was the comment in the April 1873 Chess Record about this composition by B.M. Neill. The problem was also given on page 123 of Chess in Philadelphia by G. Reichhelm and on page 27 of the February 1922 American Chess Bulletin. In the latter source, Walter Penn Shipley pointed out that Neill had composed the problem before he was 20 and that Reichhelm had initially believed it to have no solution.

Mate in four

Further to the discussion above regarding this problem by Sam Loyd (Mirror of American Sports, 10 October 1885), Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL; USA) writes:

‘The Mirror of American Sports chess column is available on-line from the Cleveland Digital Library. Loyd’s composition was published as “Tourney Problem No. 6” under “S.S.”:

The tourney was described as follows:

“The Mirror of American Sports’ Third Problem and Solution Tourney, for the solving championship of the world, will begin with the issue of 3 October 1885 and continue five months, ending 27 February 1886.”

I believe that this announcement came in the issue of 3 October; although the column in question is not dated, it precedes the 10 October one, and elsewhere in that column it is noted that “The Fun Begins Today” in reference to the tourney. It is sometimes difficult in the pdf file to determine where columns end and begin.

The solution was given in the 28 November 1885 issue, where the dual 2 Bb8 was noted.

Another interesting note was published under “Chess Chips” in what appears to be the 26 December 1885 issue:

“Mr Loyd writes, ‘I saw Zukertort today, and he solved the “S.S.”! Do you think it prognosticates anything?’ It may have ‘prognosticated’ that Zukertort had seen the problem and ‘tumbled’ to it before he left the old country.”

This, of course, is in reference to the upcoming match between Zukertort and Steinitz.

There is nothing indicating that Loyd revised the problem to reflect S. Pickard’s rendition.

The winner of the tourney was Johann Berger, followed by G.C. Reichhelm and with B.G. Laws in third place.’

(7472)

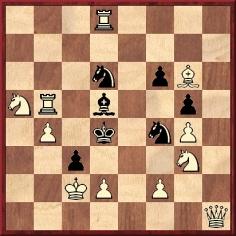

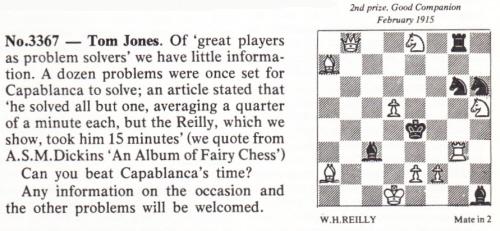

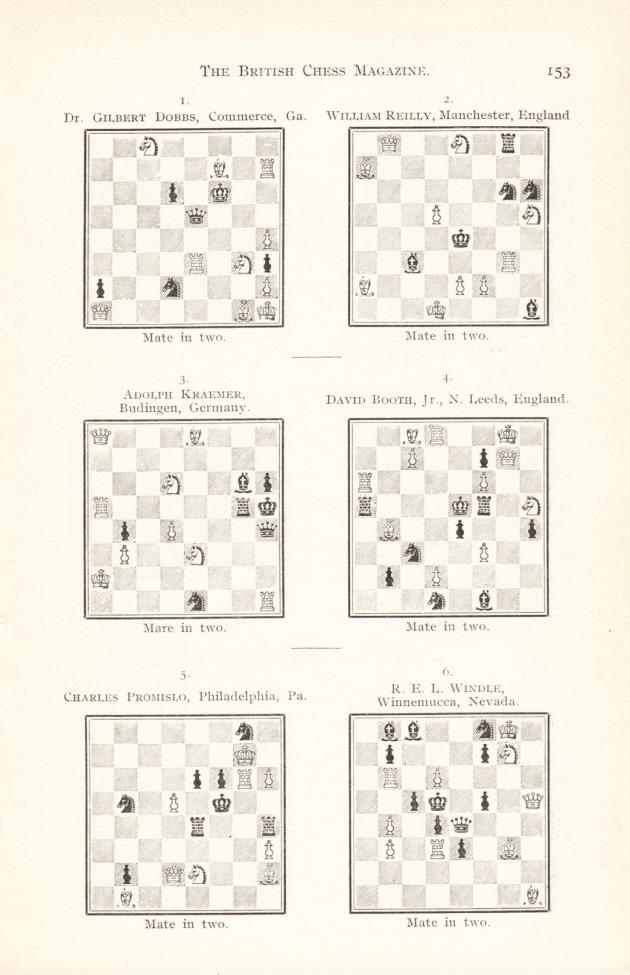

Readers wishing to test their problem-solving skills against Capablanca are invited to time themselves while trying to find the key move in this position:

Mate in two

The problem, by William Reilly, was one of 12 in the International Good Companion Two-Move Solving Tourney held on 22 February 1915. Clubs around the world were invited to organize a solving session and to submit their results to the Good Companion Chess Problem Club in Philadelphia.

The problem by Reilly was published by D.J. Morgan on page 397 of the September 1973 BCM:

We are grateful to Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) for providing the relevant text on page 4 of Dickins’ An Album of Fairy Chess (London, 1970):

‘William Henry Reilly

Born 5 October 1892 at Salford, Lancs. Member of FCCC from 1958, and of BCPS from 1968. Fairy problems published in Chess Amateur, The Problemist, Fairy Chess Review and Feenschach. Orthodox problems also in Manchester City News, Manchester Weekly Times, Manchester Guardian, Daily Mail, Western Daily Mercury, Birmingham Daily Post, Daily News, Daily Telegraph and The Chess Problem. Many were reproduced in Australian papers. Mr Reilly has solved orthodox and Fairy problems as a regular solver in all of these journals at various times. Nos. 23 and 24, the only orthodox problems in this Album, are included to mark Mr Reilly’s having also been an orthodox composer, No. 24 being probably his first problem, while No. 23 won the 2nd prize in the Good Companion tourney in February 1915. The latter was included among a dozen problems set for Capablanca to solve; an article stated that “he solved all but one, averaging a quarter of a minute each, but the Reilly took him 15 minutes”. One of his off days?

Mr Reilly has won about 40 prizes (about half of them 1st prizes) and about the same number of mentions, commends, etc. He was a solver in Fairy Chess Review for the complete 27½ years of its existence without a break, and finished up as Champion Solver with 79 ladder ascents and 38 Top of the Month honours. His FCCC contributions have now reached nearly 380, all originals except one, and a third of them subsequently published in Feenschach.’

Dickens then gave 22 annotated fairy compositions by Reilly and two orthodox problems, including the mate-in-two under discussion here.

Mr McDowell adds:

‘I have been unable to find any obituary of Reilly in The Problemist. His last original fairy contribution to the magazine appeared in the January 1983 issue.’

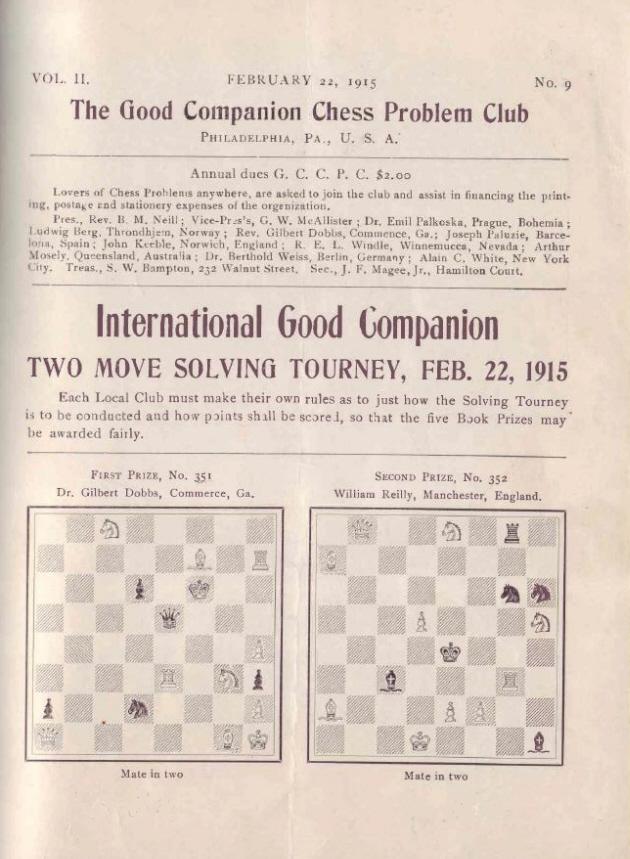

Our correspondent has also sent us, courtesy of Brian Stephenson, the extensive coverage of the problem-solving competition which was published in The Good Companion Chess Problem Club in 1914 and 1915. The 12 two-movers appeared on pages 47-49 of the 22 February 1915 issue, and below is the first of those pages:

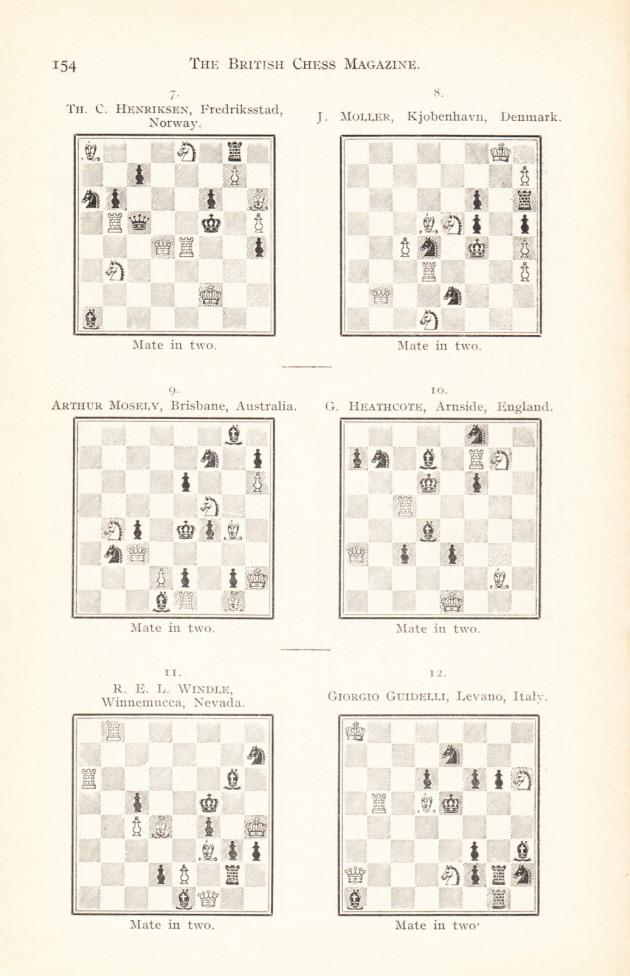

The full set was also given on pages 153-154 of the April 1915 BCM:

The Good Companion publication reproduced extensive reports on the solving competition which were received from club secretaries in various countries, and on pages 93-94 of the 1 May 1915 issue Frank Janet (the pseudonym of Elias Silberstein) presented the minutes of the session held at the Manhattan Chess Club. Edward Lasker solved 11 of the 12 problems in one hour 27 minutes, and Frank J. Marshall solved eight in 37 minutes. Regarding Capablanca, the following was reported by Janet:

‘José R. Capablanca solved all 12 in 15 minutes. Capablanca’s ability to solve problems is nothing short of miraculous. He had 11 of them in 11 minutes. The Reilly, No. 352, held him for four minutes. After the Tourney was over I put a series of swift positions of my own and he had the answers for each almost as soon as it struck the board. He wishes to state that he did not officially enter the Tourney, as he felt it might be unfair to the others, but solved the problems in order to show his interest. He does not wish to be considered for a prize.’

We do not know why Dickins stated that Capablanca took 15, rather than four, minutes on the Reilly composition (key move: 1 Rg2).

(8006)

Further examples of particularly difficult problems are sought. For example, page 320 of the October 1885 International Chess Magazine reported that J. Mieses took 34 minutes to solve the following composition by Franz Schrüfer of Bamberg:

Mate in four

The key move is 1 f6. Among the many possible lines is 1…Bxf6 2 Ng5 Bxe7 3 Nh7 any 4 Qe4 mate.

This composition was given on page 13 of A Chess Omnibus.

For further information about the Washman/Wasmann problem, see A Chess Washout.

A mate-in-three problem by Will H. Lyons which Steinitz and Mackenzie found difficult to solve was discussed in C.N.s 6757 and 6762. The Pulitzer problem above was first given by us in C.N. 2185 (see page 41 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves).

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.