Edward Winter

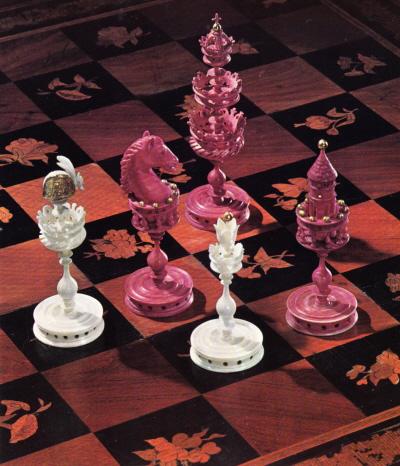

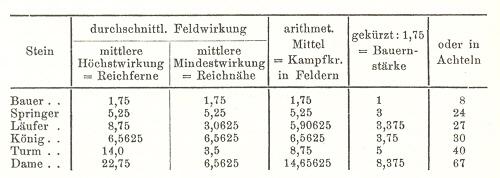

Illustration 99 in Chess: East and West, Past and Present (New York, 1968)

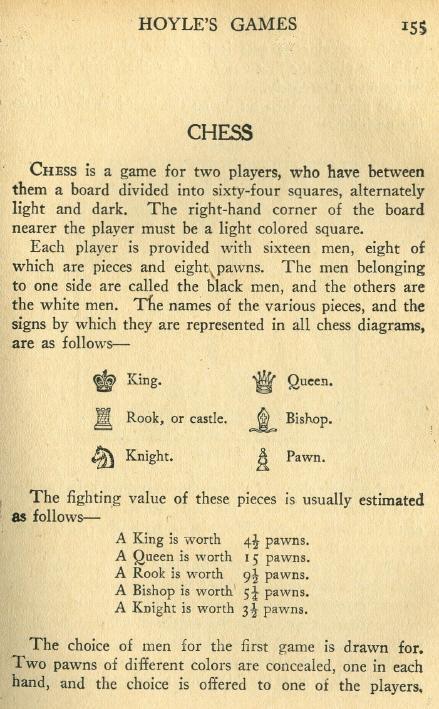

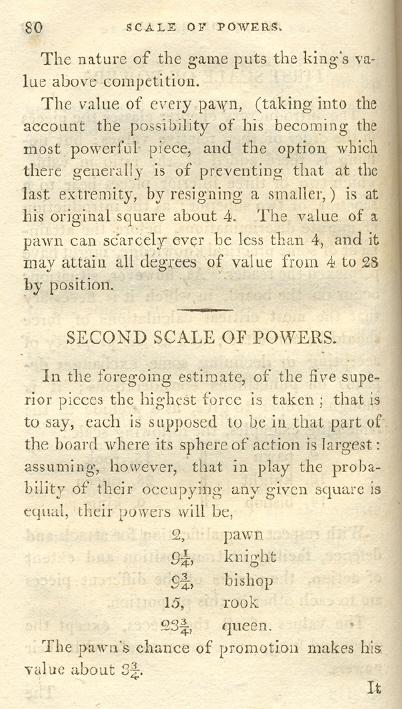

Matt Goddard (Hiram, GA, USA) mentions a peculiar list of piece values on page 155 of Hoyle’s Complete and Authoritative Book of Games (the 1952 edition from Garden City Books, Garden City, New York, originally published in 1907 by the McClure Company):

Our correspondent writes:

‘Are there other examples where these were given as the common values, and where specifically did these values originate?’

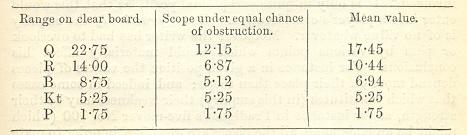

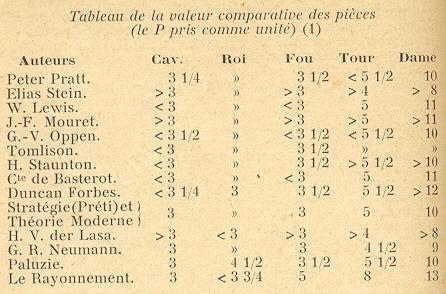

In no other edition of Hoyle that we have consulted is the queen valued at more than ten pawns, and the evaluations given in the illustration above are certainly unauthoritative. Below we briefly list some further examples (pre-Second World War) of how this subject has been treated.

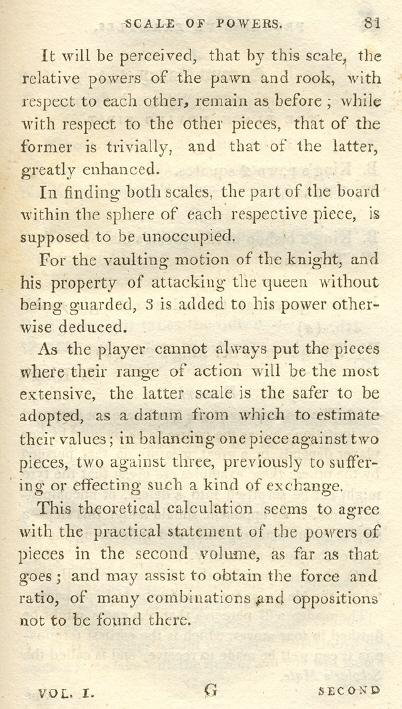

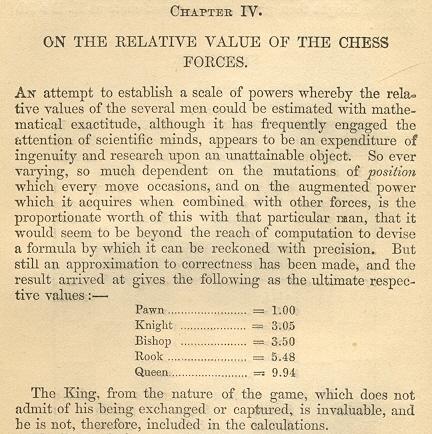

The ‘final relative values’ (page 136) were:

pawn: 1.00

knight: 3.05

bishop: 3.50

rook: 5.48

queen: 9.94.

Pierce then explained the conclusions in the Biddle paper:

‘The author lays down the law that the entire value of a piece is the product of its separate values for attack and defence. He shows that the value of a piece for defensive purposes varies inversely as its entire value and directly as its mean scope. Hence the square of the entire value is equal to the product of its attacking value and mean scope.

Thus we get ultimately the entire values Q=10, R=5.84, B=3.53, Kt=2.89, P=.5.’

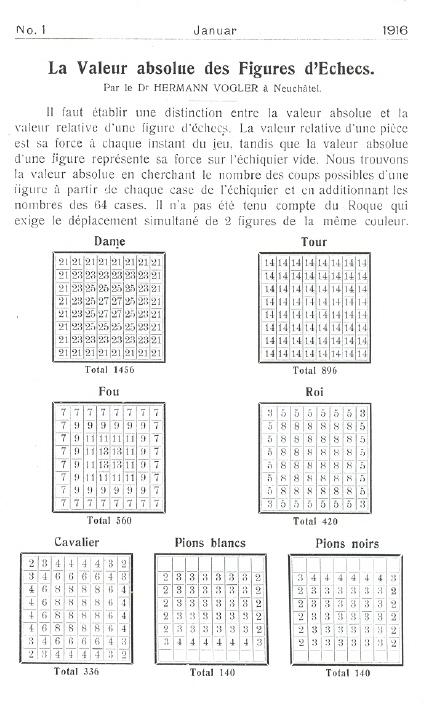

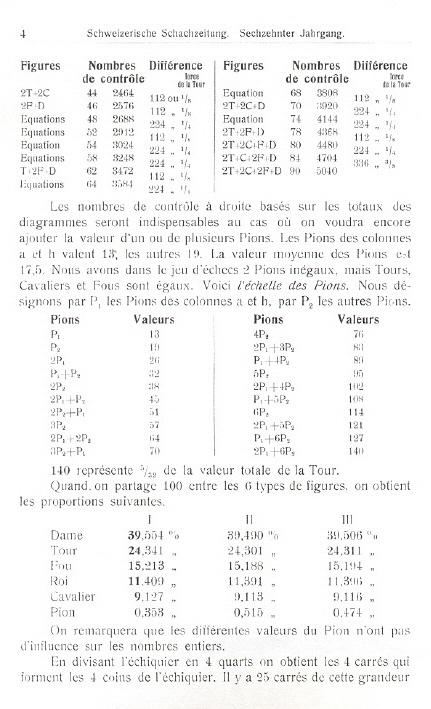

Page 83 of the March 1916 BCM gave a tepid reception to Vogler’s ‘curious’ article, although on page 125 of the April 1916 issue a reader, S.H. Gould, opined that the BCM had dismissed it too lightly. Vogler’s article was reproduced on pages 65-70 of La Stratégie, March 1916.

The above listings are, of course, by no means exhaustive but offer an overview of the old-timers’ attempts to allocate exact values to the chess pieces.

(4897)

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

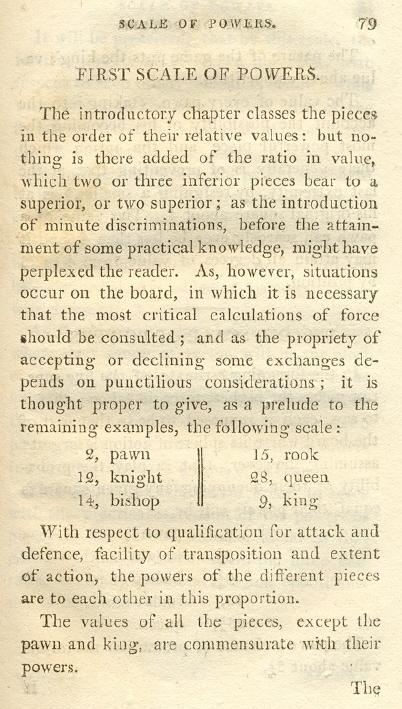

‘Page 57 of my publication The Hall-of-Fame History of US Chess (1998) has an article tracing the scale of powers that were given in Amusements in Chess and in Staunton to an earlier source: an 1817 edition of Philidor’s analysis, apparently done by Peter Pratt. In that edition, Pratt devoted 40 pages to mathematical analysis of various factors, leading to his concluding scale of Q=9.94, R=5.48, B=3.5, N=3.05, P=1. He suggested rounding off the scale, but Staunton and Steinitz printed it with full decimal places.

I have subsequently found that Pratt, as early as 1805 and probably earlier, gave two different scales, based on different lines of reasoning. The first scale had P=2, N=12, B=14, R=15, Q=28, K=9, whereas his second scale was P=2, N=9.25, B=9.75, R=15, Q=23.75, no K value. Apparently Pratt later developed the mathematical analysis printed in 1817. The same figures were used not only by Staunton in his Handbook but also by Steinitz (on page xxxiii of The Modern Chess Instructor), and ultimately became our modern scale.’

(4902)

A question from Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA): who introduced the famous elementary system of values (pawn 1, knight 3, bishop 3, rook 5, queen 9)?

We can do no better than quote from page 59 of The Hall-of-Fame History of US Chess by Robert John McCrary (1998):

‘By the 1930s, the idea of a single numerical scale of values seemed to be losing favor. Instead, great players such as Capablanca and Tarrasch were generally avoiding giving a single scale of values in their books, preferring to discuss various kinds of exchanges on a case-by-case basis.

Then in 1942 Reuben Fine published his Chess The Easy Way. On page 23 is the following historically important section:

“Since there are six different kinds of pieces it is necessary to set up a table of equivalents in order to be able to know whether an exchange is favorable or not. Again such a table is based partly on the elementary mates (R can mate, B or Kt cannot) and partly on practise. If we take the pawn as 1 we may set up a table such as this:

pawn = 1

bishop (or knight) = 3

rook =5

queen =9.”Fine goes on to say that his table is satisfactory for rough calculation but not as accurate as a set of equivalents for certain exchanges he gives on the next page. Nevertheless, Fine apparently popularized our modern scale and indeed may have invented it. Does any reader know of an earlier publication of the modern scale? Perhaps Fine then should be considered the true “point-count” man of chess.’

(7853)

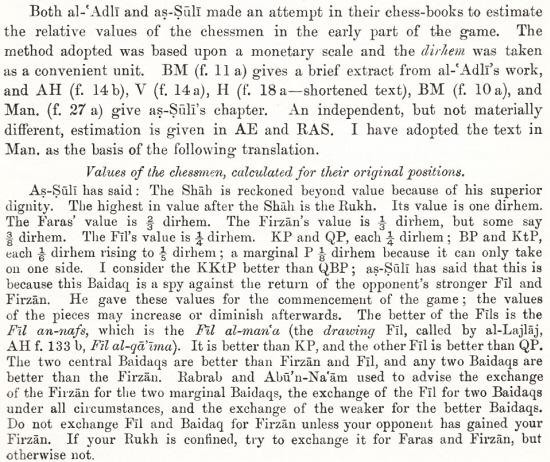

Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA) notes this passage on page 227 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913):

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

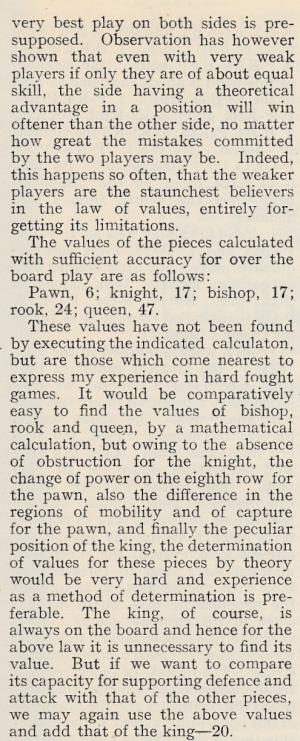

‘Lasker’s Chess Magazine published a series of copyrighted articles by Emanuel Lasker on basic chess instruction, and on pages 188-189 of the August 1905 issue he discussed the value of pieces. After describing the methods of Jaenisch and the mathematician Euler, he gave, on page 189, a peculiar scale:

“The values of the pieces calculated with sufficient accuracy for over the board play are as follows:

Pawn, 6; knight, 17; bishop, 17; rook, 24; queen, 47.

These values have not been found by executing the indicated calculation, but are those which come nearest to express my experience in hard fought games.”

Lasker then added some provisos and concluded by giving the king a value of 20.

I have yet to find any occurrence of these values elsewhere in Lasker’s writings.’

(8859)

Robert John McCrary refers to an 1857 edition of Hoyle’s Games by Thomas Frère:

‘Frère was a significant chess author, so this edition is more accurate on chess than other works bearing the “Hoyle’s” name. Moreover, Frère’s Preface, dated March 1857, makes it clear that the book is original and unrelated to Hoyle’s traditional works. It states (page iii):

“There isn’t a line of ‘Hoyle’ in it. Hoyle is a fossil, and suited only to fossil players.”

Although my copy is dated 1875, it seems to be an essentially unaltered reprint of the 1857 edition. All the chess content appears consistent with early 1857.

On page 235 Frère writes:

“Relative value of the pieces. The relative value of the pieces is estimated as follows: the queen is worth, say, 10 pawns; the rook 5; the bishop 3½; the knight 3½.”

This is the earliest publication that I have seen which gives the bishop and knight the same value.’

(8885)

A further contribution from Robert John McCrary:

‘Page 137 of Games and Sports by Donald Walker, published in 1837 by Thomas Hurst, London, suggests a scale of values for chess pieces. The relevant section reads:

“The values of the men – These have been calculated as merely regulating the odds sometimes given at the beginning of the game; for their value during the game must depend greatly on situation. The value of the pawn being taken as one; the knight is worth rather more than three; the bishop is of similar value; the rook is worth about five pawns, or two pawns and a knight or bishop; the queen is worth about ten pawns, and is therefore the most powerful of the pieces.”

‘However, on page 138 it is stated that the queen’s relative value is diminished toward the end of a game, when rooks have a “clearer” board and thus more power relative to the queen.’

(8904)

Robert John McCrary writes:

‘Page 334 of The Boy’s Own Book, Improved Edition (Boston, 1851) has this in its chess section:

“The value of the men has been estimated as in the following proportion to each other: the queen, 95; a rook, 60; a bishop, 39; a knight, the same as the bishop; the king (estimated as a fighting piece) 26; a pawn, 8, or rather more, from its chance of promotion ...”

A chess set owned by Jon Crumiller, dated approximately mid-1800s, has a handwritten sheet inside its box, with the same values as those given above, but with the knight as 37 (the bishop is still 39) and the pawn “rather more than 9”. The rook is called “castle” on that sheet.

The first American edition of The Boy’s Own Book (Boston, 1829) states it was taken from a London book whose year is not given (although page 26 The Tecumsehs of the International Association by Brian Martin (Jefferson, 2015) says Boy’s Own Book was published in England in 1828) and that a “long treatise on chess” in the London work was omitted.

According to the Boston, 1829 edition, the reason for omitting “a long treatise on chess” from the English edition, as well as articles on several other pastimes, was that those articles would add to the cost but were “entirely useless on this side of the Atlantic” and would “have given no real additional value” to the book. The fact that chess was included in the 1851 “Improved” American edition indicates the game’s growth in popular esteem in the United States between 1829 and 1851.’

We note the following on page 25 of Easy Guide to the Game of Chess by Charles Check (London, 1818):

‘Value of the men. This has been estimated, reckoning their power of attack and defence only, as in the following proportion to each other. The queen 95: a rook 60: a bishop 39: a knight 37: the king 26: a pawn 8. The intrinsic value of the king, however, is, from the principle of the game, inestimable: and that of the pawn, from it’s [sic] chance of promotion, is calculated at 15.’

(9652)

From pages 36-37 of A Complete Guide to the Game of Chess by H.F.L. Meyer (London, 1882), whose notation was discussed in C.N. 4589:

‘The relative value depends on the position, for sometimes an O is better than an M, or a P may be superior to the L, but the following numbers will give the general approximate value. Let P=1, then O=3, N=3, M=5, L=10; and the K is invaluable, but its power for defence and attack is about 3. (Some authors reckon O, N and M a fraction higher.)

As a rule 3 Ps are equal to a minor officer; 2 minor officers equal to an M and 2 Ps; the L equal to the 2 Ms, or to 3 minor officers.’

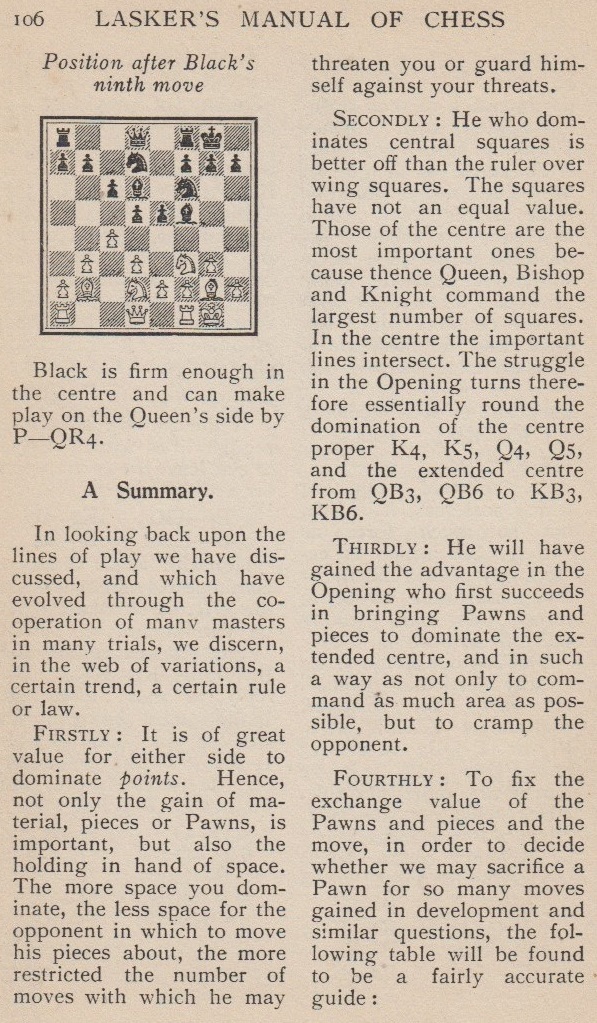

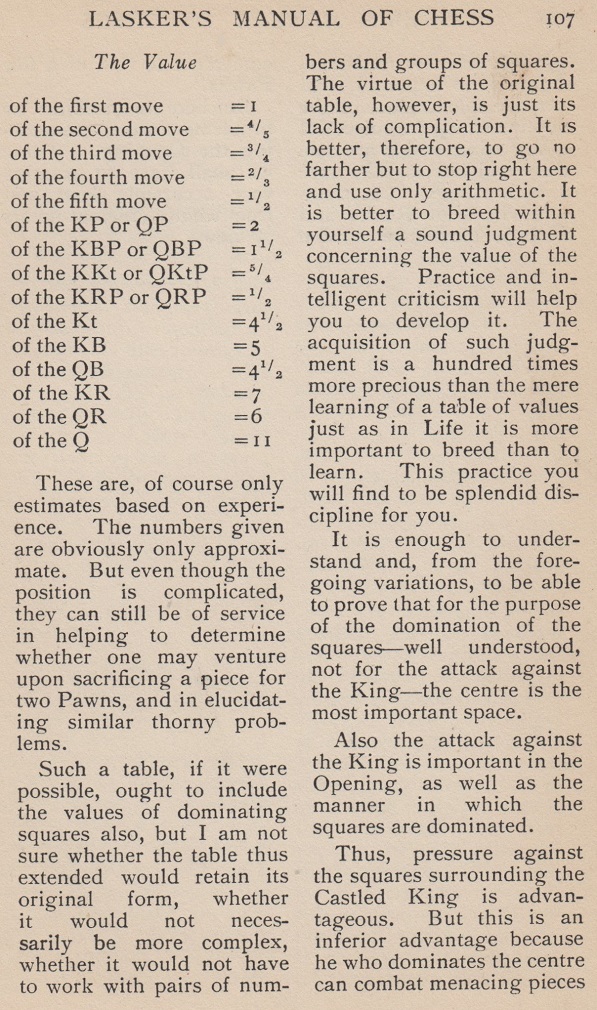

An addition is provided by Peter Banks (Oldbury, England), from pages 106-107 of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (London, 1932):

In the original English-language edition (New York, 1927), the text was on pages 119-120.

(10631)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.