17 November 2022. This is an extensively abridged version of the writer’s investigation into the controversial occurrences at the 1939 FIDE General Assembly. Those wishing to study the matter in greater detail are referred to the full report.

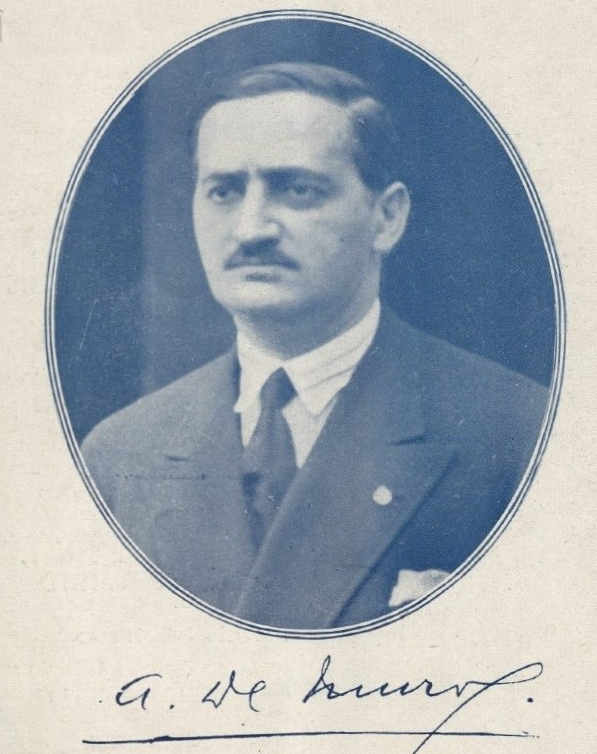

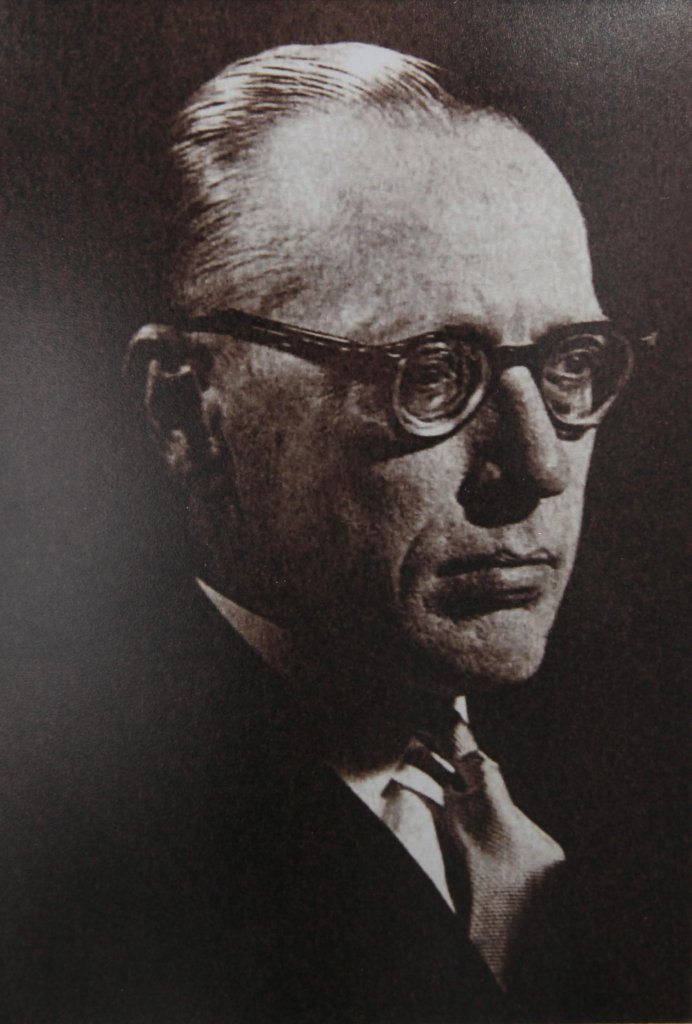

Augusto De Muro, born in 1886 or 1887 in Buenos Aires, for decades one of Argentina’s leading sports journalists and editors. He was elected President of the Argentinean Chess Federation in 1929 and again in 1937.

He was a well-known public figure, also presiding over the Automobile Club Argentina and other organizations. His connections were a key factor behind the 1939 International Tournament. He died on 16 November 1959 in Buenos Aires.

(Jaque Mate, May 1929, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library and of Chess Notes)

Was it a brazen coup? Or just a call of duty in turbulent times?

The 1939 “Tournament of Nations” in Buenos Aires is unique in chess history, remembered for wonderful tales and harrowing stories, celebrated in dozens of articles and some exceptional books. Among its forgotten tales, though, is one that almost split FIDE in two and has recently been brought into the limelight. An Argentinean motion now proposes amending FIDE’s official presidential history by recognizing the chief organizer of the 1939 tournament, Augusto De Muro, as the second FIDE President, for the years 1939 to 1946, instead of the Dutchman Dr. Alexander Rueb, whose term of office is traditionally given as from 1924 to 1949.

Sifting through old chess magazines and newspapers, one finds relevant reports on the 1939 FIDE Congress. It was held alongside the international tournament, and on 18 September, the penultimate day of play, a controversial, unannounced vote resulted in support (by 8 to 0 votes) for replacing the incumbent FIDE President, Alexander Rueb, by Augusto De Muro, the President of the Argentinean Chess Federation.

This was a significant event but, when reported at all, it was mostly buried among accounts of the sporting outcome of what is nowadays termed the “Chess Olympiad.” The chess tournament itself was overshadowed by the outbreak of World War II one third of the way through the event. After the War, when FIDE reconstituted itself at its 17th Congress in Winterthur, Switzerland, it continued with Rueb as President as if nothing had ever happened, and the Buenos Aires intermezzo was quickly forgotten. FIDE remained in Europe, with Rueb its President until 1949.

Does this part of FIDE history need rewriting? Has Augusto De Muro been unjustly neglected by chroniclers of FIDE?

FIDE from 1924 to 1939

The World Chess Federation (FIDE) was founded on 20 July 1924 in Paris, France. Its daily business was entrusted to a Central Committee of three people, elected for four-year terms of office during the General Assembly, which was held annually. From 1928 onwards, the Committee consisted of the President, Alexander Rueb from the Netherlands, the Vice-President, Maurice S. Kuhns from the United States, and the Treasurer, Marc Nicolet from Switzerland.

FIDE membership grew from thirteen nations in 1925 to thirty-three in 1938. For most of that period Argentina remained the only Latin American country. However, in the year preceding the 1939 Olympiad, twelve more federations joined FIDE, many of them from Latin America, attracted by the prospect of playing in Buenos Aires.

From an official gathering at the Buenos Aires 1939 Olympiad, taken during a Captains’ meeting or perhaps even a session of the General Assembly. On the far left, speaking, seems to be Augusto De Muro.

(picture courtesy of Jurgen Stigter)

The 1939 FIDE Congress

Dr. Alexander Rueb (1882–1959), lawyer and judge in The Hague. He was the first FIDE President, and for over two decades he was synonymous with the Federation, which he led from 1924 to 1949.

(picture: Livre d’Or de la Fédération Internationale d’Echecs, 1976)

The 16th Congress of FIDE took place in the last week of the Buenos Aires team tournament. Tensions arose between Alexander Rueb and the South American representatives, the most notable of whom was Luciano Long Vidal of Argentina, who made several rather sharp criticisms of FIDE and invited delegates to visit the offices of the Olympiad organizers, to see how efficiently it was handling matters related to communications and documentation.

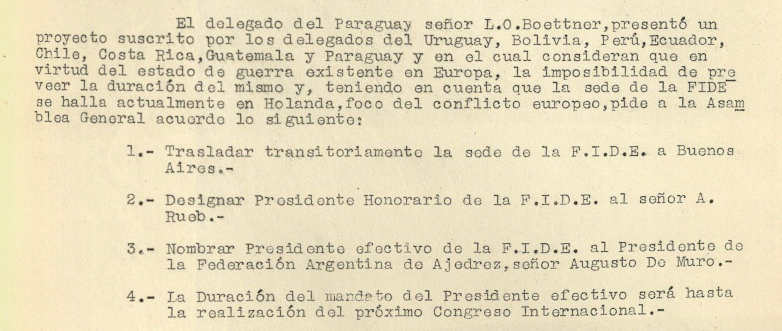

At the end of the fifth and final official session of the General Assembly, the Paraguayan delegate, Dr. Luis Oscar Boettner, requested the floor. In view of the War in Europe and the exposed location of Holland, where FIDE had its headquarters, he foresaw great dangers for the continuation and development of FIDE’s activities. He therefore put forward a motion that FIDE’s headquarters should be moved temporarily to Buenos Aires, that Rueb should be elected Honorary President, and that the President of the Argentinean Chess Federation should be appointed as the acting President of FIDE, with his mandate to continue until the next FIDE Congress. The motion was co-signed by the delegates from Uruguay, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Costa Rica, and Guatemala.

Rueb argued that no elections were on the agenda and that the proposal, not having been announced prior to the Congress, violated FIDE’s Statutes and Regulations. The General Assembly, whose working session at this point consisted mostly of Latin American representatives, chose to follow not Rueb’s view but that of the Peruvian delegate, Dr. José Jacinto Rada, who claimed that “according to the letter and the spirit of the Statutes, the General Assembly was the supreme authority of FIDE, and that it could thus adopt any resolution.”

A vote was held. Six South American nations (Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay) and two European countries (Denmark and Lithuania) voted in favour of the controversial motion. Estonia, France, Germany, and Argentina abstained, the last-named as a “matter of délicatesse” although it was clearly in favour of the proposal and, presumably, its spiritus rector.

Rueb left the meeting, having declared that he would not accept the decisions, which he regarded as illegal. The General Assembly continued without him, and the next day it had its decision ratified by a total of nineteen delegates. No further debate took place, however, and it is unclear how many delegates were aware of all the circumstances and of Rueb’s objections.

Two Presidents, two sets of minutes.

Left: The account by Rueb in the traditional FIDE format of the day, November 1939.

Right: The account by the Argentinean Chess Federation, May 1940.

(pictures courtesy of FIDE/Willy Iclicki and Juan Sebastián Morgado)

Formally, the War in Europe was given as the reason for moving FIDE to Buenos Aires, but growing discontent with Rueb was also a factor, and perhaps even the greater one. This was revealed by, for instance, Roberto Grau (1900–1944), a co-founder of FIDE, “father of the 1939 Olympiad,” and the top board of the Argentinean team:

[N]otable federation and club directors, who in the first hour were indispensable elements for success, unfortunately fail later on, and they have to be violently ousted from the positions they consider their own property. For many years, FIDE has been a prime example of this. …

Dr. Rueb became, little by little, the dictator of FIDE, and a traveller who every year had his wife’s expenses paid to attend the congresses, which had to work through dumb agendas, and to solemnly inaugurate the big team tournaments, FIDE’s only effective activity. It was necessary to put an end to such an abnormal state of affairs. Rueb had turned the FIDE presidency into an asset of his own; in the debates he respected the agenda when it suited him, and incorporated matters when they were brought up by him or by the Swiss Federation, which followed him faithfully. …

This means that there was perfect agreement and that the desire was evident to remove Dr. Rueb from the post which he had retained by always evading responsibility for his actions … (¡Aquí Está!, 18 May 1940)

The frustration which had built up over the years is evident. With the congresses taking place in far-away locations and with elections timed inconveniently, it was hard for South Americans to bring about any changes. But now the outbreak of the War, together with the absence of many of the European delegates, offered an unexpected opportunity to change the situation radically.

The controversial proposal by Boettner, from the pages of the tournament’s daily bulletin, no. 23, 19 September 1939.

(picture courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library and Justin Corfield)

Was the “De Muro Presidency” legitimate?

Dr. Luis Oscar Boettner (1900–1972), Paraguayan chess champion, politician, and in 1949 briefly a member of Paraguay’s Supreme Court. He proposed relocating FIDE and the Presidency to Buenos Aires.

(picture Corte Suprema de Justicia, Paraguay).

In legal terms, the vote in Buenos Aires was almost certainly invalid. 1939 was not an election year, and the proposal to relocate FIDE and to oust Rueb had not been properly announced in advance and should thus not have been on the agenda at all. Both the FIDE Statutes and the applicable Swiss Civil Code leave no doubt about that. Meanwhile, the clause granting “supreme power” to the General Assembly can hardly have meant that the latter could violate its own Regulations and Statutes whenever it might wish to.

Both the legality and the legitimacy have to be questioned. Although the circumstances were exceptional, they were not of the kind that justified the forcible ousting of the President without due process. Several legal options existed within the framework of FIDE to bring about a change or to mitigate the impact of War. For instance, the Vice-President Maurice S. Kuhns was an American and thus far from the War zone. He could have been entrusted with continuing FIDE’s business in case of need. Kuhns, incidentally, was regarded by both Rueb and De Muro as being on their respective sides. After initially congratulating De Muro, however, Kuhns soon retracted his words. Once the full picture emerged and he had heard from both parties, he came down on Rueb’s side, describing the Buenos Aires FIDE as “spurious” (see CHESS, June 1941, page 131).

The Paraguayan motion was an obvious violation of democratic principles. Only about half the members of FIDE were represented in Buenos Aires, and even fewer knew that such an important vote was being held. Ultimately, only eight of the forty-five member nations had voted against Rueb. Not surprisingly, some commentators spoke of a “coup.”

Reaction in Europe to the news from Buenos Aires fell short of the “perfect agreement” postulated by Grau. It was lukewarm at best and derisive at worst.

In the end, the “De Muro Presidency” existed primarily on paper. Apart from a few speeches, De Muro did not continue with FIDE’s activities during the War years. No reports were produced, no gatherings held, and no membership fees collected.

Summary

In conclusion:

-

The 1939 vote to replace Rueb by De Muro and move FIDE’s headquarters to Buenos Aires was a violation of the Federation’s Statutes, committed by an unrepresentative minority and, essentially, behind the back of the other member nations. Growing discontent with the incumbent President was just as much a motive as geopolitical considerations. The “De Muro Administration” faced opposition from overseas from the outset and never became truly productive.

In the 21st century, it seems ill-advised for FIDE to endorse retrospectively an illegitimate and illegal attempt to usurp power, and particularly given that the action had little practical impact at the time, except for increasing FIDE’s paralysis during the War.

Augusto De Muro, Roberto Grau, and others deserve great admiration for organizing a splendid Chess Olympiad in 1939, after overcoming countless obstacles. There are far better ways of honouring their names than rewriting FIDE’s presidential history. Launching a proper gallery of honorary members and founders of FIDE would be a welcome first step.

The author is grateful to Justin Corfield, Juan Sebastián Morgado, Jurgen Stigter, and Edward Winter, as well as Raymond Rozman and William Chase from the Cleveland Public Library, who generously provided various materials for this article. All opinions expressed are those of the author.

Download the full 30-page report on the investigation, including exact references, etc.:

fide1939_report_forster.pdf

Published: 17 November 2022.

Postscript of 4 December 2022:

A few minor objections have been raised, privately or publicly, to the above report. Here are some thoughts on them:

- “FIDE Rules and Statutes have been broken in many other years, too, also in connection with presidential elections.”—Clearly the lack of legality or legitimacy of the 1939 proceedings is not altered by any such future incidents. Moreover, those later cases differ in a significant respect: On all the occasions when Campomanes or Ilyumzhinov bent the rules in their favour, these were known to be election years. A large majority of members were represented and thus gave, at least implicitly, their stamp of approval.

- “True, De Muro was not very effective as FIDE President in the period 1939 to 1946, but neither was Rueb.”—The observation is correct, but it confirms that the Presidency should “by default” be regarded as Rueb’s. Rewriting history that was uncontested for decades requires very convincing arguments. Otherwise, if it becomes arbitrary and subject to preferential changes, history loses its relevancy. A strong burden of proof applies to the view that aims to challenge the traditional view. Thus, given the lack of formal justification, any claim for a “De Muro Administration” must rest on strong evidence of actual accomplishments (for which there is no evidence).

- “In the first post-War Congress in Winterthur, 1946, Rueb was elected by only a handful of nations. Was that any more legitimate than the 1939 vote?”—Yes, it was much more legitimate. The 1946 election was announced in advance. Every member nation had the opportunity to send a delegate or appoint a proxy to vote in the election. While in 1939 many members did not even know about the “election,” in 1946 everyone was properly informed. Those who chose not to be represented did so of their own free will.

Incidentally, the Congress in 1946 did the opposite of the 1939 Congress: As the meeting minutes show, the 1946 Congress voluntarily decided that its decisions, including the election, should only be valid for one year and until the next Congress took place, when a more numerous and representative participation was hoped for. - “It was Rueb’s own fault for bringing the proposal to an actual vote. If he considered it illegal, he could just have refrained from holding the vote.”—To assume that this would have changed the course of events is naive. The delegates were willing to take matters in their own hands, as shown by the continuation of the session and the scheduling of yet another session after Rueb had already “abruptly left the meeting” (Argentinean version) or “closed the Congress” (Rueb version). It is illusionary to believe that the delegates would have quietly dispersed, had Rueb just closed the session without discussion or vote. By holding the vote himself, rather than having others hold it in his absence, Rueb was at least able to know the outcome first-hand and to include it in his official account.

Postscript of 11 February 2023:

See also Chess Notes item 11935, which mentioned a further article by Richard Forster, “Buenos Aires 1939: The putsch that did not happen,” on pages 40-42 of the February 2023 CHESS.