Edward Winter

(2004, with additions)

George Hatfeild/Hatfield Dingley Gossip (Columbia Chess Chronicle, 18 August 1888, page 55)

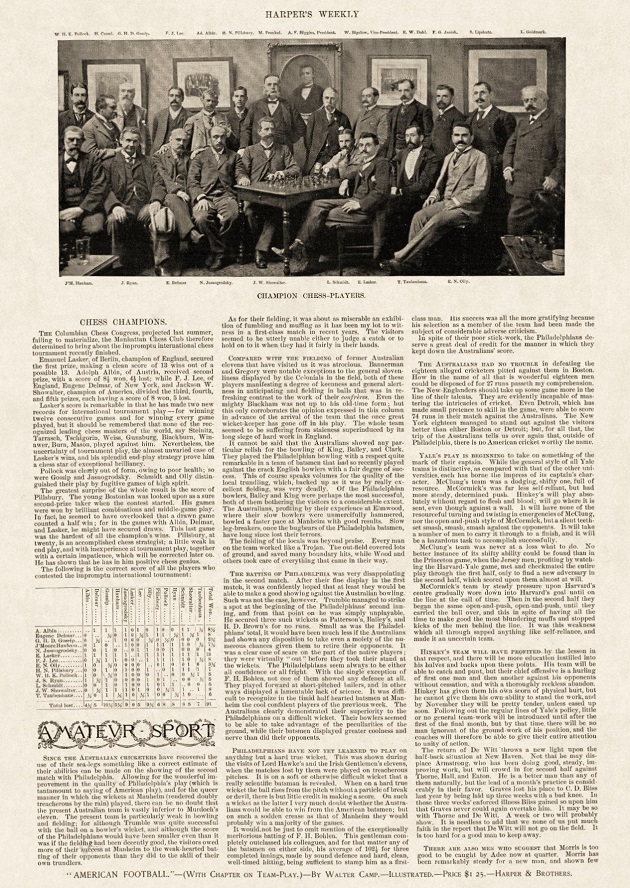

We are grateful to HarpWeek LLC for permission to reproduce a group photograph which appeared in Harper’s Weekly at the time of the New York, 1893 tournament:

From left to right in the back row: W.H.K. Pollock, H. Cassel, G.H.D. Gossip, F.J. Lee, A. Albin, H.N. Pillsbury, M. Frankel, A.F. Higgins, W.Bigelow, E.W. Dahl, F.G. Janish, S. Lipschütz and L. Goldmark.

Front row: J.M. Hanham, J. Ryan, E. Delmar, N. Jasnogrodsky, J.W. Showalter, L. Schmidt, Em. Lasker, J. Taubenhaus and E.N. Olly.

(3240)

The New York, 1893 shot in C.N. 3240 is the only photograph of G.H.D. Gossip that we recall, although a sketch accompanied an article about him on pages 55-56 of the 18 August 1888 issue of the Columbia Chess Chronicle presented the following biographical details:

‘Mr Gossip was born in Franklin Street, New York City, on 6 December 1841. His mother, Mary Ellen Gossip, oldest daughter of Mr Chas. Dingley, died when he was only 16 months old, at 55 Bond Street, on 8 May 1843 (vide New York Herald of 9 May 1843). About two years after his mother’s death his father (an Englishman) brought him to England, where he was brought up at Barlborough Hall, Derbyshire, the seat of his aunt, Mrs Reaston Rodes (the “Bracebridge” as well as the Barlborough Hall of Washington Irving, vide Abbotsford and Newstead Abbey, page 164), and at Hatfield, in Yorkshire. Mr Gossip, who was educated at Windermere College, Westmorland, could have taken a scholarship at Oxford, but owing to the loss of a lawsuit by his father, uncle and aunts, which utterly ruined them, was unable to go to Oxford, and has had through life to depend on his own exertions. He lived for over five years in Paris, where he held several appointments and contributed to some French newspapers. From 1879 to 1880 he was employed occasionally as translator and otherwise in the London Times office, 22 rue Vivienne, Paris. During a residence of over four years in Australia he has been engaged in journalistic work, and has contributed leading and other articles to the Sydney Australian Star, Globe, Evening News, Town and Country Journal, Adelaide Advertiser, etc.; besides literary articles in the Melbourne and Sydney magazines, Once a Month and the Sydney Quarterly Magazine. In San Francisco he contributed articles on the ‘Chinese Question in Australia’ and on ‘Protection and Free Trade in New South Wales’ in the San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle respectively.’

The most extensive overview of Gossip’s life, G.H. Diggle’s article ‘The Master Who Never Was’ on pages 1-4 of the January 1969 BCM, strove to be fair, but Gossip has always been a soft target for mockery. Below is what appeared on page 168 of The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1993):

‘Of players who’ve entered chess history, perhaps the strongest claimant for the all-time grandpatzer title is George Hatfeild Dingley Gossip (1841-1907). George had a worse record in major tournaments than anyone in history (last at Breslau 1889, London 1889, Manchester 1890, London 1892, and New York 1893: a total of just 4 wins, 52 losses and 21 draws). This didn’t prevent him from promoting himself as a great player; nor did it inhibit him from writing a series of instructional books on the game. These contained a number of flashy (and entirely fictitious) wins he’d scored against famous players; and in one of them he proudly published the summit of his achievement: third prize in the Melbourne Chess Club Handicap Tournament 1885.’

We take up just three points:

1) What is put forward as Gossip’s ‘record in major tournaments’ conspicuously omits the event in which he produced what G.H. Diggle called ‘perhaps the best performance of his career’: New York, 1889. Gossip scored +11 =5 –22, did not finish bottom and secured victories over Lipschütz, Judd, Delmar, Showalter, Pollock (twice), Bird (twice), D.G. Baird, Hanham and J.W. Baird. Regarding Gossip’s win against Showalter, Steinitz commented on page 388 of the tournament book:

‘One of the finest specimens of sacrificing play on record. Mr Gossip deserves the highest praise for the ingenuity and depth of combination which he displayed in this game.’

2) ‘A number of flashy (and entirely fictitious) wins.’ The entry on Gossip in the 1984 edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess (which treated him essentially as light relief) stated that ‘he was accused of publishing fictitious games in which he supposedly defeated well-known players’, but this passage was dropped from the 1992 edition (which dealt with him more equitably, although it too omitted any mention of New York, 1889). Gossip himself denied the charge in an item on pages 201-203 of the July 1888 International Chess Magazine:

‘With regard to the slur thrown on me by the mean insinuations made that some of these games were never played at all, I may observe that my veracity has never been called in question except by a few unprincipled persons and their dupes.’

We should welcome a list of the games, flashy or otherwise, which Gossip is deemed to have invented.

3) ‘… in one of [his books] he proudly published the summit of his achievement: third prize in the Melbourne Chess Club Handicap Tournament 1885.’ This too is reminiscent of an assertion in the Gossip entry in the Oxford Companion. To quote the 1992 edition’s wording: ‘He was not at a loss when recommending himself to readers: ‘Third Prize in the Melbourne Club Handicap Tourney, 1885’ seemed to him an adequate testimonial.’

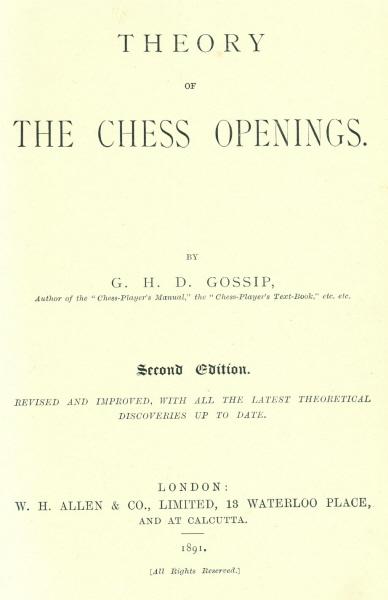

But what actually appeared in Gossip’s output? Page v of the 1891 edition of his Theory of the Chess Openings contained a biographical note on him, 16 lines long. Far from the Melbourne, 1885 result being presented as ‘the summit of his achievement’, it was simply one of 16 deeds listed.

(3241)

C.N. 3241 above criticized on three counts the disparaging treatment of G.H.D. Gossip on page 168 of The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James. On pages 58-59 of the May 2004 CHESS the co-authors accept our criticisms and state that their only defence is that they used to trust unquestioningly one of the writers of the Oxford Companion to Chess, their source.

The third of our strictures was that, taking its cue from the Companion, The Even More Complete Chess Addict mocked Gossip for presenting his modest Melbourne, 1885 result as ‘the summit of his achievement’. Although the CHESS item gives the impression of quoting our full rebuttal from C.N. 3241, it omits our reply on this third matter, i.e. the paragraph in which we pointed out that Gossip’s book Theory of the Chess Openings gave his Melbourne, 1885 result as merely one deed in a list 16.

(3289)

Concerning the Oxford Companion to Chess, see our feature article Reliability Eroded (Kenneth Whyld).

An illustration included in C.N. 3241:

In early 1888 a new edition of Gossip’s The Chess Player’s Manual was published with a 122-page appendix by Lipschütz, and Steinitz reviewed it on pages 137-138 of the May International Chess Magazine:

‘There was a great stir and commotion in the chess literary circles of England when this book made its first appearance in London, about 14 years ago, and quite a newspaper raid was made on the author and his work by various writers in different periodicals. In justice we feel bound to say that the author had brought a great deal of this adverse criticism upon himself by some reprehensible peccadillos. Mr Gossip had given a handle to ridicule by according to himself on the front page titles and airs as the winner of an insignificant correspondence tournament for which only a few obscurities had entered, and by describing himself as an active or ex-member of various clubs for which, of course, he deserved no more credit than thousands of other chessplayers who join chess societies and pay their annual dues. We are glad to see, by the way, that most of those pompous announcements have been omitted in the new edition. More serious, however, was the charge against the author in reference to his own games which he published in the Manual, and it is only just to say that he had richly deserved at least some of the sharp criticisms that were directed against him in that respect. For Mr Gossip had practiced the unfair ruse of carefully preserving stray skittle games which he had happened to win or draw, generally after many defeats, against masters whose public records stood far above his own, and who had not the slightest warning of his intention of publishing such games until they found those unprepared efforts immortalized in his book as specimens of relative skill either in the analysis or in the game collections without the least acknowledgement of their own victories, thus leading the public to believe that the author stood on a par with them, or was even their superior.

Such trickeries had, of course, the effect of prejudicing the critics against the author and his book, but I feel bound to say, after some careful perusal of the latter, that Mr Gossip has produced a useful work, which in some respects must be regarded even superior to that of Staunton or any other previous writers on the chess openings. … But the most meritorious distinguishing feature of the Manual is the large collection of illustrative games by various first-class masters, and in that respect Mr Gossip’s work stands second only to Signor Salvioli’s Teoria e Pratica among the analytical works in any language.’

Gossip replied to Steinitz on pages 201-203 of the July 1888 International Chess Magazine. He denied that the players in the correspondence tournament had been ‘obscurities’ and explained that he had mentioned his clubs ‘to let chessplayers (to whom my name was then comparatively unknown) know that I had mixed in Metropolitan chess circles, and therefore had some good practice’. He then turned to the ‘more serious’ charge of having published so many of his own won games. After writing ‘my defence to this charge is that I simply followed the example and precedent of Staunton and other authors’, he quoted a lengthy defence of himself which had appeared in the Academy of 12 December 1874. Gossip added to Steinitz:

‘Such is my defence. Nearly all these games were contested in public rooms in London for a pecuniary stake, no stipulation whatever being made as to their non-publication. I admit that I made a serious mistake in not giving the scores of my opponents, and to this indictment alone I plead guilty. But as I was then living in a remote country village where I had no chess practice for more than five years, and was quite out of the chess world, I never even in my dreams imagined that the public would suppose me to be superior to all my opponents. I might as well have supposed that they would think me equal to yourself, because my Manual contains a game which I drew with you on equal terms, and my worst enemy, I imagine, would not believe me conceited enough for that. I can only plead guilty to an error of judgment in having too hastily published these games. Every rose has its thorns, and there is no cloud without a silver lining; and perhaps I have unwittingly rendered a great service to future chess authors, inasmuch as my sad fate will be a warning to them to all eternity not to commit the deadly sin of which I have been guilty, and they will thus steer clear of the breakers on which I have been shipwrecked. I may here, however, flatly contradict the mendacious assertion of the critic in the London Sportsman “that nearly every player of whom I won the games published in the Manual was vastly and immeasurably my superior”. Out of 24 opponents I won a majority of games of 15. Your accusation of trickery therefore, I think, falls to the ground.’

Gossip then replied to the accusation of having invented games (see his words quoted above). He concluded by quoting a number of critics who he said had noticed his book favourably, including Löwenthal on pages 297-304 of the January 1875 City of London Chess Magazine. Our own reading of Löwenthal’s review is that it was considerably more negative than Gossip suggested.

Steinitz’s response (on pages 204-205 of the July 1888 International Chess Magazine) acknowledged that Gossip ‘has some just cause of complaint especially in reference to a writer, now deceased, who within a few days after the publication of the book which had cost the author two years of labor, assumed to consign the whole work of over 800 pages to a sweeping condemnation’. This seems to be a reference to John Wisker’s review of the Manual in the Sportsman. See page 10 of Cathy Chua’s 1998 book Australian Chess at the Top (Oaklands Park, 1998).

However, the world champion maintained his ‘obscurities’ remark and continued:

‘As regards the selection of games for publication, Mr Gossip is, we fear, only aggravating the case in pleading that he merely followed the example of Staunton. For he must have known, being well enough acquainted with chess history, that the practice of Staunton in ignoring the victories of his opponents or rivals caused a great deal of bitter feeling against him, albeit he was a celebrated player and author. Mr Gossip could have easily, therefore, concluded that his imitation of such a practice would be held still more unpardonable in the case of a new rival for fame who had not earned his spurs yet at that date. We still think, therefore, that he had exposed himself to some of the sharp, adverse criticism that was directed against him at the time. But we quite concur with Mr Gossip’s claim that his book was too harshly treated in consequence …’

Even Steinitz’s fair-minded comments were subsequently used against Gossip, as was reported on pages 70-71 of the Columbia Chess Chronicle, 1 September 1888:

‘Mr Gossip has been much wronged by false accusations made against him both in the English and Australian chess press. For instance, the Melbourne Australasian, in a recent issue, in noticing Mr Steinitz’s review in the International of the third [sic] edition of Mr Gossip’s Manual suppresses all mention of the high praise conferred by that eminent critic on the work in question (which Steinitz declared to be in some respects superior to the work of Staunton or any previous authors), and only refers to Steinitz’s condemnation of the course pursued by Mr Gossip in publishing only his victories and suppressing the publication of his defeats in the Manual, and adds “that Mr Gossip practiced the same course in Australia”. Now, so far from this being true, we have before us the back files of the chess column of the Sydney Town and Country Journal, which Mr Gossip edited for a considerable time in Australia, in which we see that Mr Gossip repeatedly published games which he lost in club matches, etc., in Sydney to Mess. Russell, Heimann and others. We state this in the interest of fair play.’

In the 1890s Gossip was still bitter over the critics’ treatment of his books. In 1891 he brought out an updated version of Theory of the Chess Openings, which began with four pages of commendatory quotes on the first (1879) edition from reviewers such as Steinitz, Duffy and Delmar. At the bottom of page x Gossip added a note:

‘Such are a few only of the favourable reviews of the first edition of the present work, which received the highest praise from the best authorities in England, America and the Continent. Yet it is never even once referred to in Mr Bird’s latest treatise. Under these circumstances, it is not, perhaps, surprising that I was unable, even with £50 worth of signed orders for copies, to find any publisher willing to undertake the publication of a second edition, although I made strenuous and unceasing efforts to publish it before I sailed for Australia in February 1884. However, perseverantia omnia vincit, and I have at length succeeded in bringing out the present work, in spite of incessant opposition, disparagement and non-recognition.’

The last mention of Gossip that we have found in the contemporary chess press is this brief paragraph on page 59 of the June 1897 American Chess Magazine:

‘Another Buffalo player who should be mentioned is H.D. Gossip, who has written several books. Mr Gossip’s play is very strong.’

As G.H. Diggle’s BCM article pointed out, although P.W. Sergeant referred in 1916 to ‘the late G.H.D. Gossip’ (i.e. on page 1 of the January 1916 BCM), it was not until the mid-1960s that the date of Gossip’s demise became known to the chess world. On page 306 of the October 1964 BCM David Hooper reported that Gossip had died of heart disease at the Railway Hotel, Liphook, England on 11 May 1907.

One final curiosity. George Hatfeild Dingley Gossip left Australia in 1888, and we have yet to find any reference to his returning there. Yet a website gives details of a ‘George Hatfield Dingley Gossip’ born in Sydney in 1897.

(3245)

Pages 91-92 of the 15 September 1888 issue of the Columbia Chess Chronicle reported on a lecture about the Steinitz Gambit delivered by Gossip two days previously. His remarks were not confined to openings analysis:

‘Before his departure for America, Mr Steinitz told me that he considered his gambit sound, notwithstanding his defeat in the London tournament of 1883, when he adopted his favorite opening. This is an important point of theory, and it will be well, therefore, to show how utterly worthless is the analysis of this début published in the Illustrated London News and the Illustrated (London) Sporting and Dramatic News, both of which periodicals declared in the most confident and positive manner that Black could obtain a draw by checking backwards and forwards with his queen on his seventh and eighth moves [1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 d4 Qh4+ 5 Ke2 d5 6 exd5 Qe7+ 7 Kf2 Qh4+, etc.] …

In order, therefore, to establish an important point of theory, and at the same time to prevent American chessplayers from being misled and deceived by the superficial analysis of incompetent British chess editors, whose object in condemning the Steinitz Gambit has obviously been mainly to depreciate the originality of its illustrious inventor, whom they invariably try to drag down to their own miserable level of shallow incompetency and self-conceit, I submit the following variations which at any rate possess the undeniable merit of exposing the hollow analytical twaddle continually published in the two London journals above named. American chessplayers are all the more likely to be imposed upon in as much as the British Chess Magazine declares the chess editor of the London Sporting and Dramatic News [G.A. MacDonell] to be a most accomplished master, and the Illustrated London News asserts that the death of its late chess editor [P. Duffy] leaves a void that cannot be filled.’

For the last few months of 1888 Gossip was listed as being on the ‘Editorial Staff’ of the Columbia Chess Chronicle. On pages 218-229 of the 29 December 1888 issue he contributed a lengthy general article which, though entitled ‘Chess in the Present Day’, offered a broad sweep of chess history and the advances made by the game in the United States. ‘In no other country in the world, with the solitary exception, perhaps, of intellectual Germany, does chess flourish as in America.’ He described Morphy and Steinitz as ‘the two greatest chessplayers that have ever lived’. What little criticism the article contained focussed on England: ‘no Englishman has yet attained, or probably ever will attain, to the eminence of chess champion of the world. … The deep-thinking German, the brilliant Frenchman and the versatile American have always been too much for sober, stolid John Bull.’

Finally, with regard to the last paragraph of C.N. 3245 Brad Dassat (Oldham, England) writes:

‘You remarked that Gossip left Australia in 1888, and that there are details of a George Hatfield Dingley Gossip on an Australian website about World War One aces. In fact, this point was picked up on in an article by Ken Whyld in the BCM (July 2001, page 391). This was a follow-up to an earlier article by Whyld on Gossip in the BCM (May, 2001, pages 262-265). The WW1 ace Gossip was apparently the grandson of the chessplaying Gossip.’

George Hatfeild/Hatfield Dingley Gossip (detail from New York, 1893 group photograph)

(3254)

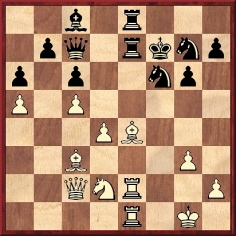

That G.H.D. Gossip could not expect equitable treatment from Zukertort and Hoffer’s magazine the Chess Monthly was shown by pages 102-103 of the December 1883 issue, which reviewed the London, 1883 tournament book. Although Gossip (‘this tedious mediocrity’) had played only in the minor (Vizayanagaram) tourney, almost half the extensive review was given over to an attack on him. Regarding his win over G.A. MacDonnell the Monthly commented, ‘the latter played like a child, and that game ought not to have been published’. The tournament book (pages 336-339) also had Gossip’s notes to his game (as Black) against W.M. Gattie, which had begun 1 Nf3 Nc6 and eventually reached this position:

Here Gossip played 41…Bf5 and wrote:

‘The only possible move to avoid loss. In this extremely difficult and interesting position Black took 25 minutes for reflection before writing down his 41st move at the adjournment.’

The Monthly scoffed:

‘We have examined the “extremely difficult and interesting position” and can only say if it took Mr Gossip 25 minutes to find such an obvious move, how long would it have taken him to find a really difficult move? Well, the answer is easy enough: he would not have found it at all.’

(3284)

In C.N. 4879 Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) provided information regarding Gossip from British censuses:

1871 census: George Gossip, age 29. Born in New York (British subject). Address: 8 Mayfield Road (Hackney), London. Occupation: translator of languages. Married with Alicia Gossip (age 30, born in Dublin). Child: George Gossip (son, age 11 months). Other household members: Charlotte Pripke[?] (age 16), general servant; Lucy Pripke[?] (age 12), nursemaid.

1881 census: George H.D. Gossip, age 39. Born in New York, United States. Address: 1 Lilian Villas, Spring Road (St Helen), Ipswich. Occupation: author of work on chess. Married with Alice Gossip (age 40, born in Dublin). Children: Helen J. Gossip (daughter, age 9), Harold K. Gossip (son, age 7), Mabel M. Gossip (daughter, age 2).

1891 census: G.H.D. Gossip, age 49. Born in New York as a British subject. Address: 20 Alfred Place (St Giles), London. Occupation: literary profession. Widower. Gossip, a lodger, shared the address with: William Belcker[?] (age 49), lodger and assistant brewer; Gustav Dürholdt (age 24), lodger and electric engineer; W. Edmund James Leach (age 32), lodger and captain in army; Alexander Mackintosh (age 54), commercial traveller; Janet [surname illegible] (age 53), head and lodging house keeper; Lizzy Chapman (age 19), general servant (domestic).

In C.N. 4883 Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) presented a photograph of Gossip’s house in that town.

Is ‘George Hatfeild Dingley Gossip’ correct? That has been the customary spelling of chess writers ever since publication of the Oxford Companion to Chess in 1984, but what were the Companion’s grounds for switching from the previously used ‘Hatfield’? While recently processing our feature article on Gossip we felt uneasy, as on some earlier occasions, about ‘Hatfeild’, and not least because part of his education took place in Hatfield, Yorkshire.

Tim Harding (Dublin) comments that a specimen of Gossip’s signature given in the May 2001 BCM, page 265, ‘does seem to support the Hatfeild spelling’. He adds, further to the Gossip entry in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987), that the reference for the death certificate mentioned by Gaige is Petersfield 2c 84. Does any reader have a copy of the certificate?

As indicated in C.N. 5075, the ‘Hatfeild’ spelling became common usage after its appearance in the Oxford Companion to Chess in 1984. Earlier, the Companion’s co-authors had used ‘Hatfield’ on page 306 of the October 1964 BCM (D. Hooper) and on page 408 of the September 1979 BCM (K. Whyld). As noted in C.N. 3245, it was Hooper who revealed, in 1964, where and when Gossip died (in Liphook, Hampshire, England on 11 May 1907).

(5100)

A negative view about Kenneth Whyld was expressed to us by Jeremy Gaige (letter dated 5 November 1990) in connection with the spelling of Gossip’s second forename:

Addition on 29 October 2024:

John Townsend writes:

‘Official records of the coroner’s inquest into Gossip’s death have not survived, according to information on the website of the Hampshire Record Office. The following report appeared in the Portsmouth Evening News, Tuesday, 14 May 1907, page 5:

“Tragic death at Liphook

At Liphook on Monday an inquest was held at the ‘Railway’ Hotel concerning the death of Mr George Hatfield Dingley Gossip. The deceased was a great traveller and a well-known literary man. He was a writer of books on chess. He belonged to Thorp Arch, Yorks., and had lately been staying at Northcote House, Liphook, for the benefit of his health. Mr Gerald Fitzgerald, of 11 Oakwood Court, Kensington, identified the body. The evidence of Miss Churchman, who lives at Northcote House, showed that the deceased complained of feeling sick at the dinner table on Friday last, but the next morning told her he felt better. Albert Bridger, a fishmonger, lodging at the ‘Swan’ Inn, Petersfield, stated that he happened to be in the ‘Railway’ Hotel, Liphook, on Saturday morning when the landlord’s son, knowing he had been a billiard-marker, asked him if he would play billiards with the deceased. He did so, and after they had played three or four games, and whilst they were engaged in another, the deceased, who was in the act of playing, suddenly fell to the floor dead, without the slightest warning. Deceased had previously appeared to be quite well, and was not excited at all. Dr Shelmerdine proved that the death was due to heart disease. The jury returned a verdict accordingly, and the Coroner (Mr Goble) commented on the pathetic circumstances and expressed sympathy with the deceased gentleman’s relations.”

The above is in keeping with the commonly accepted date of death, 11 May 1907. There is an entry for him in the indexes of deaths in the second quarter of 1907 in the registration district of Petersfield (volume 2c, page 84); the age given is 65.

Regarding the question of “Hatfeild” or “Hatfield”, I find the evidence divided. It is true that the spelling “Hatfeild” is used of the chessplayer in Burke’s Landed Gentry: for example, in the 1937 edition, on pages 1072-1073, it is found in the article on the family of Hatfeild of Thorp Arch, which was connected to the Gossips by marriage. The Hatfeilds are traced back to Elizabethan times, and that spelling, clearly, has deep roots. However, time marches on, and there is no law which says that spelling must be retained by all descendants.

No article on the Gossip family is to be found in Burke’s Landed Gentry, according to Burke’s Family Index (a bibliography of the many Burke’s publications, by Rosemary Pinches, published by Burke’s Peerage Ltd., 1976).

However, another Burke’s publication, Burke’s Family Records (edited by Ashworth P. Burke, 1897) which covers some of the lesser, “cadet” branches of the nobility, does contain an article on the Gossip family (pages 265-267). It refers to the chessman as:

“George Hatfield Dingley Gossip, of Hatfield, W.R. Yorks., b. 6 Dec. 1841, bapt. at Hatfield, near Doncaster, 3 June, 1847, m. 3 Oct. 1868, Alicia, only dau. and heir of Joseph Kenny, B.A. and M.B., of Stoke Newington, Middlesex, and by her, who d. 14 Oct. 1888, has issue ...”

This contradicts the spelling found in Burke’s Landed Gentry. “Hatfield” is also given as the spelling of the parish of that name (“Hatfeild”, as printed in Burke’s Landed Gentry, is not normally found).

There is considerable evidence elsewhere which supports the “Hatfield” spelling in Gossip’s name. The 1847 baptism entry referred to above has “Hatfield” for both the child and parents, George Hatfield Gossip, esquire, and Mary Ellen (source: Hatfield parish register, 3 June 1847, Doncaster Archives, viewable on-line at Familysearch.org). When Gossip died in 1907, the index to deaths gave “Hatfield”, and so did his burial entry in the Thorp Arch parish register. Similarly, “Hatfield” was the spelling used in the National Probate Calendar for 1870, when Susanna Augusta Gossip, a spinster, of Doncaster, appointed her nephew, George Hatfield Dingley Gossip, as executor of her will, which was proved on 30 May.

There is also evidence in support of “Hatfeild”, including Tim Harding’s comment that a specimen of Gossip’s signature given in the May 2001 BCM, page 265, ‘does seem to support the Hatfeild spelling’. Also Gossip’s application form to the Royal Literary Fund, 3 December 1890, filled in by G.H.D.G., contains “Hatfeild”. It was shown in C.N. 8185.’

On 29 October 2024 our feature article on Gossip was augmented by John Townsend with a note on Gossip’s death and on the spelling of one of his forenames (Hatfield or Hatfeild?). The ‘normal’ spelling (i.e. ie) was seen until the mid-1980s, when evidence grew in favour of ‘Hatfeild’. However, Mr Townsend’s note shows a mixed picture, and at present the safest full form may be ‘George Hatfeild/Hatfield Dingley Gossip’.

(12059)

The signature (on a letter dated 10 September 1881) on page 265 of the May 2001 BCM reads ‘G. Hatfeild D. Gossip’. Gossip letters (from East Bergolt, Colchester and dated 8 April 1874 and 15 January 1875 respectively) were published on pages 103-104 of the May 1874 City of London Chess Magazine and page 62 of the March 1875 edition; they ended ‘G. Hatfield D. Gossip’.

Chess Morganisms quotes D.J. Morgan on page 185 of the June 1959 BCM:

‘The quip about Gossip pottering and Potter gossiping at a club is a pretty old one (W.N. Potter, 1840-1895). In chess it seems that longevity is the soul of wit.’

No early occurrence of the quip has yet been found. Searching in Chess Life-Pictures (London, 1883) and The Knights and Kings of Chess (London, 1894), we noted that in neither of G.A. MacDonnell’s books was Gossip even mentioned.

C.N. 5710 quoted extracts from the pen portraits of participants in New York, 1889 which were published on page 8 of the New York Times, 16 June 1889. Below is the full text concerning Gossip:

‘Gossip, with his long, flowing beard, looks like one of the old-time monks. He has a good-shaped cranium, bald at the top, and is a little above the medium height. Although an Australian by adoption, he was born in this city. He believes himself to be one of the greatest chessplayers in the world, and thinks that if everything had gone on to his liking he could have beaten all the champions at the tournament. He is a deliberate player, but every now and then he takes a nip from a flask of brandy that generally stands on his table. He complained that his chair was too low, and he once attributed a defeat to that. Finally, he got a large ledger and sat upon it. He did, in fact, seem to derive some inspiration from its contents, for he played two or three excellent games afterward.’

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) writes:

‘I have found that G.H.D. Gossip apparently published a book, not about chess for once, entitled The Jew of Chamant. Page 86 of The Library Journal of February 1899, issued by the American Library Association, shows that “Trepoff, Ivan”, the pseudonym of “G. Hatfield Dingley Gossip”, brought out “The Jew of Chamant; or, the modern Monte Cristo”, published by Hausauer of Buffalo, NY in 1898. Another source indicates that the book was published in 1899 by F.T. Neely (London and New York) as “The Jew of Chamant: a romance of crime”.’

We note too the entry in the Library of Congress Online Catalog. Can any reader find a copy of the book?

(5842)

Addition on 27 November 2008: an article by G.H. Diggle on page 13 of the 1 April 1983 Newsflash which was subsequently published on pages 93-94 of his book Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984).

‘Few men who have made chess their profession have been dogged by such persistent bad fortune as that courageous but ill-starred player, writer and controversialist George Hatfield [or Hatfeild] Dingley Gossip (1841-1907). Some of it was indeed due to his over-estimate of himself – he tried to climb “the greasy pole” much too fast. His 900-page Chess Player’s Manual, 1874, into which he put a tremendous amount of work, failed utterly, partly because his “Illustrative Games” included a large number of his own wins (some of doubtful authenticity) against some of the very same Masters who “reviewed” his book! He pluckily persevered in 1879 with The Theory of the Chess Openings which, though better received, was the victim of an act of gross piracy, as many copies forming no part of the edition printed by his orders were circulated in America and the “pirates” never brought to justice.

As a Tournament Player, Gossip was the King of Wooden Spoonists – out of the seven Master Tournaments to which he “bulldozed” admission he came last in five and last but one in the sixth, his aggregate score in all six being 4 wins, 52 losses and 21 draws. But in the seventh (the great double-round 6th American Congress, 1889) he put up his best show with 11 wins, 22 losses and 5 draws, and played the one famous game of his career, a brilliant win against Showalter. But even here, ill-luck pursued him, for this game, which should certainly have won the “Special Prize for the best played game”, was, to his great chagrin and many other people’s surprise, passed over in favour of Gunsberg v Mason.

A dauntless traveller, he tried his fortune in France, Germany, Australia, the United States and Canada, vanishing for 12 years in 1895 and finally returning to this country to die at Liphook, Hants in 1907. A trenchant letter, written by him to a friend on 20 October 1894 from “81 Cathcart Street, Montreal” shows that his resources and his opinions of his “chess patrons” were at equally low ebb: “The French Canadian Chessplayers here are the poorest, meanest humbugs I ever met – all Jesuits. An old priest promised me 10 dollars for a simultaneous, but of course a Jesuit can only be relied on not to keep his word. Another club treated me similarly. The only real patron of Chess here is an American, Mr J.N. Babson. I have only made 27 dollars in 6 weeks, 18 dollars thanks to him. A Manchester paper has published already four columns of articles by myself, for which of course I expect payment, if I am not dead before the money can reach me. A very nice man, Mr Cox, Professor of Physics at the University here, who had promised to take a course of chess lessons off me, has OF COURSE been laid up with lumbago, so I have not made a cent with him. If I go to Cuba I shall have to swim there according to present prospects ... Pollock is not much better off.”

Happily in the month following this letter, a generous Montreal amateur promoted a match between the two unfortunate players, which ended in a draw (Gossip 6, Pollock 6, drawn 5) and no doubt the prize money was shared. Pollock later returned to Bristol, where he died on 5 October 1896.’

Postscript by G.H. Diggle: ‘Gossip’s letter was very kindly given to the BM by the late David Lawson.’

Reverting to the published statement that G.H.D. Gossip wrote a work of fiction, The Jew of Chamant, under the name Ivan Trepoff, Frederick S. Rhine notes that according to page 1037 of American Fiction, 1901-1925: A Bibliography by Geoffrey D. Smith (Cambridge, 1997) ‘Ivan Trepoff’ was a pseudonym of Herman Arthur Haubold (1867-1931).

We have acquired a copy of the novel Spiritmist by Ivan Trepoff, published by Donald W. Newton, New York in 1909. The second page of the Preface was dated two years after Gossip died:

Did two writers use the same pseudonym, or was The Jew of Chamant written by Haubold, and not Gossip?

(5866)

Having traced a copy of The Jew of Chamant, a novel which G.H.D. Gossip brought out in 1898 under the pseudonym Ivan Trepoff, Frederick S. Rhine has sent us a photostat of the complete work. He comments:

‘It is a vile book, virulently anti-Semitic but also very anti-Catholic and with negative references to South Americans, American Indians, a “nigger”, atheists, socialists and Romanians. The Preface (page 3) begins:

“In the Rogues’ Gallery of France there is no more conspicuous figure than the Jew of Chamant. Dickens and Harrison Ainsworth have well portrayed the Jew in all his revolting hideousness.”

Later on the same page the author states:

“My object in the present work is to paint the rich Jew in his true colors, as the enemy of society; to show that the Jew who steals millions can, in Europe, at any rate, defy the laws with impunity, and that he almost invariably escapes punishment owing to improper occult influences, and the mighty power of Israelitish gold.”

Towards the end (page 325) he even advocates genocide:

“Such is justice on the banks of the Seine! And such will probably continue to be the travesty of justice in la belle France until the massacre of the Jews – the Hebrew ‘St Bartholomew’ – threatened by Major Esterhazy at the Zola trial, has drenched the streets of Paris with the blood of that accursed race!”

On pages 260-261 there is a reference to chess and to Kolisch:

“The Champs Elysées in Paris are the veritable Elysian fields or paradise of la haute banque juive. The very names of the streets and avenues of this world famed thoroughfare of splendid equipages innumerable are Jewish, or have a pronounced semitic ring about them. At one end, near the Triumphal Arch, in the Rue Galilée, was the luxurious hotel of the great Hebrew banker, the late Baron Ignaz von Kölisch [sic], a poor devil literally without boots in the early ‘sixties’, who used to earn a precarious living by playing chess for a stake of a franc a game at the Café de la Régence in the Rue St Honoré, and was often half-starved; but who, by the usual Hebrew methods of a fraudulent bankruptcy, the support of the ‘Israelitish Alliance’ and the patronage of the Paris Baron Rothschild, became a millionaire and also, mirabile dictu, a full fledged Baron or ‘Freiherr’ of the Austrian Empire, and actually entertained on one occasion at his princely Château in Austria the Empress of Austria and her suite. This little, ill-bred Jew, whose manners were disgusting, entertained an Empress of the proud Imperial House of Hapsburg!”’

(5994)

C.N. 5919 mentioned that Wikipedia (English edition) has an excellent article on Gossip. It was written principally by Frederick S. Rhine.

Addition on 10 January 2009:

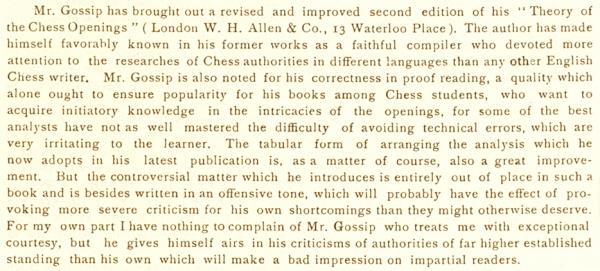

Source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, 27 March 1895, page 27.

From page 143 of the May 1891 International Chess Magazine:

(6602)

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) provides details of a chess figure who made an application for support from the Royal Literary Fund: G.H.D. Gossip.

Giving his full name as George Hatfeild Dingley Gossip, he stated on his application form that he was a widower with three children. ‘Present means and sources of income: Extremely precarious derived from magazine writing, occasional, though very rare newspaper articles and literary work. No salary, annuity or pension whatsoever.’ His income over the past year had been under £65.

The file contains three letters from Gossip to the Fund, dated 3 and 14 December 1890 and 9 January 1891.

Two extracts from the first letter:

‘Although I am an Englishman and a British subject, according to International Law, having been brought up since babyhood and educated in England; and although my father’s name – that of an Englishman born in [illegible] – is to be found in Burke’s Dictionary of the Landed Gentry, under De Rodes of Barlborough and the Hatfeild and Gossip families, I was born in America; but on the death of my mother, my father brought me to England, when only three years old, and I was brought up at the Barlborough Hall of Washington Irving, who was the guest of my late Uncle and Aunt, Mr and Mrs Reaston Rodes. Barlborough Hall is mentioned at great length by Washington Irving on page 164 of his Abbotsford and Newstead Abbey, where he gives a long account of the Christmas festivities …’

‘I have been wonderfully unfortunate, and am a confirmed fatalist. I am quite convinced that the will of my aunt, Mrs Reaston Rodes, who idolized me, was burnt by a cousin a few hours after her death, and I was thus defrauded of £10,000. ... Then my Father, Uncle and their three surviving sisters were ruined utterly in a great lawsuit, just when I could have taken a scholarship of £60 a year at Oxford from St Mary’s College, Windermere, where I was educated; so that I never had a penny except what I could earn by my own unaided exertions, and was unable to go to Oxford.

I was subsequently defrauded of a large sum of money, by a dishonest solicitor, in whom I [illegible] implicit confidence, at a time when I was too ill to attend to my affairs.’

The third letter concerned his chess writings. The underlinings are Gossip’s own.

‘20 Alfred Place

Bedford SquareTo the Committee of the “Royal Literary Fund”

Gentlemen,

With regard to my application, I beg to state that I was obliged to publish privately, through a Yorkshire printer, the first edition of my Theory of the Chess Openings, because no London publisher would entertain it, notwithstanding the fact that it was declared the best work of its kind in any language by the entire British, American and Continental Chess Press, that I had had Royal patronage, £60 worth of subscriptions, by signed orders for copies, and that my previous work – The Chess Players’ Manual, (published by Routledge five years before in 1874, and most favorably reviewed by all impartial or competent critics) had had a good sale and has since had three Editions. I was foolish enough to sell outright to Messrs. Routledge the entire valuable copyright of this book of over 800 pages which occupied my time for nearly two years for the miserable sum of £70; and although Routledge has, I am informed on good authority, made thousands by my work, he will not give me a penny, and his shabby conduct towards me has been publicly commented on in America in the columns of the Boston Post.

I have rendered great services to chess literature, and the Huddersfield College (now the British) Chess Magazine, in reviewing my Chess Manual, said that a deep dept of gratitude was due to Mr Gossip for this splendid addition to the Library of the Chessplayer (sic) …

Such are the services I have rendered at Chess and Chess literature! Yet notwithstanding this and my high position in the Chess World as a player, (having played some of the most brilliant games on record) as well as a theorist, (for I have won many prizes in public Tournaments and matches, and have just won third prize in Divan Tourney), I can obtain no chess Editorship and am literally left out in the cold.

The necessity of my application is evidently by the fact that I am utterly without resources, my sight is affected and I suffer from hernia and other ailments. For two days this week I was absolutely starving. I have no relations living, to whom I could apply, except distant ones whom I cannot trace, although I have children.

This will doubtless be sufficient, without my worrying you with long explanations and details of my extraordinary misfortunes and misery.

I remain,

Gentlemen,Yours obediently,

G. Hatfeild D. Gossip.’

The form indicates that on 14 January 1891 Gossip’s application was refused.

(7288)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) supplies the handwritten applications to the Royal Literary Fund submitted by G.H.D. Gossip and B. Horwitz.

(8185)

The parting shot in a review of G.H.D. Gossip’s The Chess Player’s Manual on pages 84-88 of the Westminster Papers, 1 September 1874:

‘In conclusion, we must mention the exterior of the book: paper and print are first-rate, but the merits of the publishers cannot compensate for the incapacity of the author.’

The review also remarked (on page 84):

‘The pages 27-34, containing the Laws of the British Chess Association, are the only pages in the book without blunders, at least blunders which can be attributed to the author.’

The following issue (1 October 1874, pages 105-106) of the Westminster Papers, which was edited by P.T. Duffy, related that a letter ‘of 11 closely written pages’ had been received from Gossip but that ‘we do not share with Mr Gossip the opinion that the public are expecting a reply from him’.

G.H. Diggle referred to the episode on pages 1-2 of the January 1969 BCM, in his article on Gossip, ‘The Master Who Never Was’:

‘This contemptuous and indeed unfair treatment would have flattened a man less courageous, and less wrong-headed, than its victim, especially as other reviews, though not so venomous, had been scarcely more favourable. Indeed, when the general chorus of groans had died down, it was thought that Gossip as an author had been disposed of for good. But suddenly in 1879 (after five years’ obscurity in the “doghouse”) he made a fighting recovery with The Theory of the Chess Openings ...’

(7575)

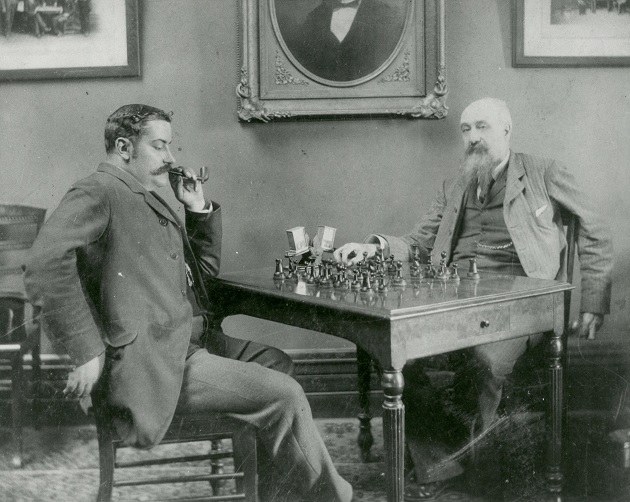

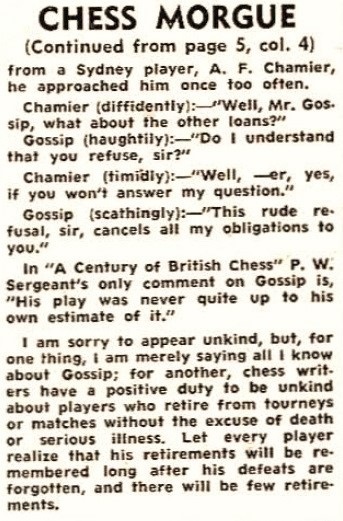

A particularly interesting photograph in Tim Harding’s new book on Blackburne (C.N. 9457) is on page 296: F.J. Lee v G.H.D. Gossip, New York, 1893 (‘courtesy Cleveland Public Library Special Collection’). We are grateful to the Library for authorization to show it here:

(9462)

A detail of Gossip:

Page 97 of Samuel Lipschütz A Life in Chess by Stephen Davies (Jefferson, 2015) quoted colourful passages about Gossip from the New York Times, 16 June 1889 and the New York Sun, 25 November 1890, page 3:

(9549)

17 July 2019: Addition from Neil Hickman (Hardingham, England):

‘As pointed out in C.N. 5075, since the appearance of the Oxford Companion to Chess in 1984 it has been customary to render G.H.D. Gossip’s second given name as Hatfeild rather than Hatfield. Burke’s Family Records lists the family of William Gossip (1704/5-72) of Thorp Arch, Yorkshire. He was a man of sufficient substance that he paid for the rebuilding of All Saints’ Church, Thorp Arch in 1756 [Borthwick Catalogue, University of York], having paid for the building of Thorp Arch Hall in 1750-54 [Historic England]. He had eight sons, the third being George (1735-75) and the youngest being Thomas (1744-76), of whom Burke’s Family Records states “see Burke’s Landed Gentry, Hatfield [sic] of Thorp Arch”.

George’s son was William (1763-1830) of Hatfield House, Yorkshire. William had three sons, William Hatfield (1794-1856), John Hatfield (born 1795) and George Hatfield (1797-1882).

George Hatfield’s only son was the chessplayer George Hatfield Dingley (hereafter “G.H.D.G.”, to distinguish him from the other four George Gossips also referred to). Although born in New York, G.H.D.G. was christened on 3 June 1847 at Hatfield, near Doncaster. Familysearch.com gives the spelling of both father and son as Hatfield, although the original record is not viewable online.

George Hatfield Gossip was an alumnus of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, matriculating at Lent 1817. Cambridge University Alumni gives his name as George Hatfeild, but that is the only instance that I have found of the spelling Hatfeild on this side of the family.

G.H.D.G. had four children, George Hatfield Herbert (born 1870), Harold Kenny (born 1873), Mabel Marie (born 1879) and Helen Josephine (born 1894).

George Hatfield Herbert was baptised on 20 May 1874 at All Saints, Haggerston; the baptism register can be viewed online, and the second Christian name of both father and son is clearly given as Hatfield. G.H.D.G. described himself as “Gentleman”.

Harold Kenny emigrated to Australia, and his son, born in January 1897, was named George Hatfield Dingley after his grandfather. He became an airman during the Great War; the database of the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians records that he was credited with shooting down six enemy aircraft. Having survived the War, he was killed in a flying accident on 24 April 1923 and is buried in Turkey. His Aviator’s Certificate shows his name as “Hatfield”. That is the explanation of the “final curiosity” noted in C.N. 3245.

However, the Hatfield/Hatfeild matter is not so straightforward. In Burke’s Landed Gentry the relevant entry is Hatfeild of Thorp Arch and Laughton. This family traces its descent from “Nicholas Hatfeild, of Shiregreen in the parish of Ecclesfield, co York (son of Robert Hatfeild, grandson of William Hatfeild, and great-grandson of Robert Hatfeild, whose father, William Hatfeild, was son of Richard Hatfeild, grandson of Ralph Hatfeild, and great-grandson of Adam de Hatfield, of Glossopdale”. Nicholas Hatfeild died in 1558 and, although his ancestor Adam was “of Hatfield”, the idiosyncratic spelling appears to have been cherished and passed down the generations. When in 1844 the direct Hatfeild line died out, the estates passed to Randall Gossip (1800-53), and according to Burke’s Landed Gentry he assumed the surname of Hatfeild by Royal Licence on 16 October 1844.

Randall was the son of Lieutenant-Colonel Randall Gossip (1774-1832) and the grandson of Thomas Gossip. His son Randall-Wilmer Hatfeild (1828-61) appears in the Electoral Register for 1857 with that spelling.

When Randall’s death was registered in 1853 (Tadcaster 9c 344) he appears with 12 individuals named Hatfield, and the index of death registrations includes a manuscript correction moving him to the correct alphabetical position above them.

Randall Hatfeild’s will was proved in the Principal Registry on 19 August 1859, and his name and the names of his executors, his widow Christiana and his son, Randall-Wilmer, were all printed incorrectly in the National Probate Calendar, and as that calendar appears online are corrected in manuscript. When the will of Randall-Wilmer Hatfeild came to be proved on 29 June 1861, the mistake was not repeated, and his name was printed with the idiosyncratic spelling.

It seems that Randall-Wilmer Hatfeild and G.H.D.G. were third cousins. Randall Hatfeild’s estate is described as “under £16,000”; that of Randall-Wilmer Hatfeild was “under £6,000”.

It is possible that G.H.D.G. adopted the idiosyncratic spelling for some extra cachet. As Ancestry.com shows, his elder daughter Helen married the son of a baronet in 1894; G.H.D.G. did not live to see his younger daughter Mabel also marrying well, in 1907, and living in Knightsbridge in a household with a nurse and four servants, as recorded in the 1911 Census.

G.H.D.G’s signature (C.N. 5100) reads “G. Hatfeild D. Goſsip”, i.e. with not only the idiosyncratic spelling Hatfeild but also the obsolescent long-s in his surname.

Although his son George Hatfield Herbert and his grandson George Hatfield Dingley both have the Hatfield spelling, the inscription on his tombstone in the churchyard of All Saints’ Thorp Arch, the church which his great-great-grandfather rebuilt, can be viewed online.’

The photograph is reproduced here with permission:

Pages 5 and 7 of Chess Life, 20 November 1957 had some comments by C.J.S. Purdy about Gossip:

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In my 2014 book Historical notes on some chess players, freemasons’ records were among the biographical sources for the chapter about Jacob Sarratt. The Library of Freemasonry in London was used, and since then many membership records of masons have been made searchable online at the genealogical website ancestry.co.uk (England, United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921).’

Below is the entry on Gossip, one of ten nineteenth-century chess personalities who were listed as masons:

George H.D. Gossip: Oak Lodge: initiated, 18 October 1871; aged 29; 8 Mayfield Terrace; gentleman.

(10101)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.