Edward Winter

One of the most important and remarkable figures in the chess world is the American Jeremy Gaige, the game’s ‘Mr Archives’. For a quarter of a century he has been compiling detailed records of events (particularly tournaments) and collecting data about chess players, composers, writers, administrators, etc.

His output, nearly all of it privately printed, includes four volumes of tournament crosstables. Published between 1969 and 1974, these contain about 2,000 tables covering the period 1851-1930. They were followed in 1984 by two volumes of Chess Tournaments A Checklist, a run-down of over 10,500 tournaments played between 1851 and 1980 with the names of winners and, where possible, the exact dates.

Gaige has produced many other books and booklets over the years. In 1987 he published two small works, Swiss Chess Personalia and Catalog of USA Chess Composers, followed by what is perhaps his magnum opus (although that term may be inadvisable given that he has produced so many magna opera). In over 500 pages Chess Personalia A Biobibliography (McFarland & Company, Inc.) aims to provide vital statistics on about 14,000 chess personalities from all countries and periods. Unlike Gaige’s much smaller earlier book, A Catalog of Chessplayers & Problemists, the Biobibliography lists sources of information and suggestions for further reading or research. Thus if the reader wishes to know about the New in Chess editor, he will find on page 426 that Jan Hendrik Timman was born in Amsterdam on 14 December 1951, became an International Master in 1971 and a Grandmaster in 1974. For further details we are duly referred to pages 36-50 of the September 1985 New in Chess, a comprehensive portrait of his career.

Retrospective ratings are also listed, allowing fascinating comparisons between players of the past and present. It cannot be claimed that the name of Gustav Neumann (born on 15 December 1838 in Gleiwitz, died on 16th February 1881 in Allenberg) is on everybody’s lips nowadays, yet his ‘Elo Historical Rating’ of 2570 is the same as the ranking of Larsen, Hort, Spassky and Spraggett in FIDE’s July 1987 International Rating List. The book also indicates official titles earned; Keres became a Grandmaster in 1950, but also an International Judge of Chess Composition in 1957 and an International Arbiter in 1974. Other recipients of the composition title, the book records, include Botvinnik and Bronstein.

Little of the information in the Biobibliography is readily available elsewhere. The entry of that fine Australian writer and player C.J.S. Purdy, for instance, lists half-a-dozen carefully selected references which will offer a well-rounded and detailed account of his life and career. (Incidentally, nearly every other chess reference book gives the wrong year for Purdy’s birth, 1907 instead of the correct 1906.) Or, to take a rather more obscure figure at random, what other chess work will help the reader who is searching for material about James Thompson? Gaige gives precise references to him in Chess in Philadelphia, the New York Clipper, the New York Herald, Turf, Field and Farm, etc. For good measure, he specifies where Thompson is buried and the reference number of his death certificate.

A glance at the six-page list of bibliographical sources confirms the thoroughly international nature of the book. To quote a few titles at random: The Austral Chess & Draughts Newspaper, Magyar Sakktörténet, Persoonlijkheden in het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, Baltische Schachblätter, Els Escacs a Catalunya, Svensk Författar Lexikon, Sto Lat Polskiej Kompozycji Szachowej. If some nationalities are relatively better represented than others, it is because a book such as the Biobibliography is only as good as the available source material. Countries such as Germany and Holland have a rich history of chess magazines – often with several titles concurrently – whereas some other countries, even where chess is popular, have endured long periods without a single specialized journal. When Capablanca died in 1942 there was no Cuban chess magazine to publish his obituary.

The sources quoted by Gaige are astonishingly far-ranging. Wherever possible he has made contact with the personalia themselves, or with their family; much information has also been obtained from funeral homes, cemeteries, local newspapers, university alumni records, professional directories, etc. Where death certificates have been obtained, the appropriate information is indicated. It is of interest to note (page 330) that the death certificate of Pillsbury, who, it used to be thought, died through excessive blindfold play, states that he succumbed to general paresis (i.e. syphilis). But there are traps too. Such figures as Fähndrich, Fleischmann and Takács had the pleasure of reading their own obituaries; Gaige carefully logs the false reports and retractions, notably in his magnificent 23-page appendix, an index of obituaries that appeared in the BCM between 1881 and 1986.

The entry for Steinitz (Elo Historical Rating: 2650) gives the reader 24 suggestions for further reading: magazine articles such as those in Československý Šach, Chess Monthly, Deutsches Wochenschach and Tidskrift för Schack, as well as books on Steinitz by Bachmann, Devidé, Hannak, Hooper and Neishtadt. Modern sources offering new research have not been overlooked: there is also mention of two significant Steinitz items in the 1986 BCM.

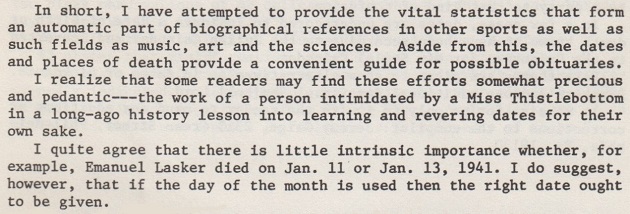

Steinitz’s birthdate is given as ‘17 (14?) May 1836’ (in Prague). When the evidence is mixed, Gaige shows which sources give which ‘facts’, and is not afraid to use question marks. He suggests that the forename of Lipschütz (born on 4 July 1863 in Ungvár, died on 30 November 1905 in Hamburg) was probably Sámuel, but notes other possibilities, including the American Chess Bulletin’s use of ‘Simon’ in 1905 and ‘Solomon’ in 1906. In his Introduction to the earlier Catalog, Gaige quoted 11 contradictory sources of information about Rudolf Spielmann’s birth and death dates, noting:

‘All too often, people assume “if it’s in print, it’s true”, especially if they are not warned that the underlying sources are so shaky. And let there be no doubt that they are. ... Whath is especially disconcerting is that none of [the sources of the Spielmann discrepancies] indicate that any of the dates are contradicted elsewhere.’

A quarter of a century of research has convinced Gaige that errors and contradictions abound. Writers frequently demonstrate lamentable carelessness, especially when an obituary has to be written at top speed with thin source material. Some magazines make do with a vague ‘died recently’ (which is little help to anybody), and even when precise dates are confidently given they cannot be accepted unquestioningly. Just because page 495 of the September 1979 Chess Life & Review categorically reported that Sidney Wallach had died on 1 July did not mean that Gaige would take this on trust. Further verification showed that Wallach’s obituary had already appeared in The New York Times of 29 June. ‘I truly wonder how the trick is done’, commented Gaige drily at the time. The Biobibliography contains the correct death date: 24 June 1979.

Gaige is a brilliant sifter of evidence, and, unlike so many chess writers, when he doesn’t know he says he doesn’t know. The birth of Charles Jaffe is given simply as ‘circa 1879, at Dubrovno’. The reasons for this are explained on page 45 of his 1980 booklet A Catalog of U.S.A. Chess Personalia, and are another example of the difficulties facing a chronicler:

‘Charles Jaffe: just when was he born?

1879, in Dubrovna, according to Jaffe’s Chess Primer, page 5;

1883, according to Chess Review, March 1933, page 2;

about 1876, in Dubrozno, according to his obituary in The New York Times of 12 July 1941, which said he died at age 65;

about 1881, according to The Day and The Jewish Journal (both New York Yiddish newspapers), which said he died at age 60;

10 December 1887, in Dubrovno, according to the Biographical Dictionary of Modern Yiddish Literature, volume 4, columns 203-204;

about 1878, according to the tournament book of Havava 1913, which gave his age at that time as 35;

As can be seen for the entry under Jaffe, I have settled upon circa 1879. But my own conjecture (which I do not put in the listings in this book) would be to assume that 10 December 1887 was a misprint for 10 December 1878. Further, I would suggest that the 10 December was Old Style, i.e. according to the Julian Calendar. If given according to New Style, i.e. Gregorian Calendar, the date would have been 22 December. Thus, in a confusion among the Jewish, Julian and Gregorian calendars, along with the confusion of a new world, an immigrant Jewish boy could have reasonably assumed that he was born in 1879. But who knows?’

How was it decided who would be included among the lucky 14,000 and who would have to be omitted? How can one reach conclusions about the relative ‘importance’ of people? The Introduction gives a detailed explanation of the difficult selection process, making the point that since ‘a prime goal of this book is to help provide the information on which to decide a person’s importance in the chess world’, it is necessary ‘to err on the side of inclusiveness’. This means that only very rarely will the reader not find a name he is seeking. When information is unavailable or uncertain, a gap is left for completion later on; it is clear that the very publication of a book of this kind will give rise to further discoveries from keen-eyed readers. As it stands, the book acknowledges assistance from a small band of helpers to whom Gaige circulated proof pages. His word-processor enables him to incorporate new information and publish updated listings with astonishing speed and accuracy.

The importance of precise data cannot be overestimated. In the case of more obscure people, the availability of exact death dates is the key to being able to trace back their lives through public records, newspaper reports, etc. Moreover, it is only when information is reasonably complete that cases of mistaken identity can be avoided. Gaige lists 24 Garcías, all but one of them still alive.

Who, then, will want a copy of this huge book? For chess writers in general (not just historians), as well as libraries, federations and clubs, it will prove an indispensable reference tool. But the ‘ordinary player’ too will turn to it again and again (certainly every time he has to play against a García). For browsing the work is an absolute joy.

The Biobibliography is one of the most useful chess books ever published, yet Jeremy Gaige would be the last person to claim that it is ‘definitive’. His work goes on, an incomparable service to the game he loves.

Afterword: This article was first published on pages 58-60 of the 8/1987 New in Chess. See also C.N.s 3595 and 3609 for further tributes to the work of Jeremy Gaige. In 2005 McFarland & Company Inc. brought out a paperback reprint of the 1987 edition of Chess Personalia.

Jeremy Gaige’s A Catalog of U.S.A. Chess Personalia was privately printed in 1980 and is a superbly researched little tome. The format is similar to Gaige’s ‘main’ Catalog, except that places of birth and death are given wherever possible. With all his research Gaige has a host of good stories about the difficulties of establishing the truth. Charles Jaffe was born ‘c1879’ but chess history has quoted 1883 almost everywhere (we have to plead guilty ourselves). Why? Mr Gaige relates that in 1933 Chess Review picked up a report of a 50th birthday party for Charles Jaffee (a man with no relation to chess) and grafted that on to Charles Jaffe.

The American Chess Bulletin reported the death in 1927 of Solomon Hecht and stated that he was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery. A check at that cemetery revealed that it was a Simon Hecht who had been interred. To quote Jeremy Gaige:

‘Perhaps the most blatant case of grafting was appropriating the date of death of the Englishman Henry Stanley to Charles Henry Stanley while transferring the location of death from England to New York City in the bargain.’

See also the BCM, 1979 pages 187-188 and 1982, pages 364-367.

One problem that constantly confronts Jeremy Gaige is that most chess writers seem to think that to put a question mark after a date is a sign of weakness, rather than strength; ‘facts’ are quoted without any acknowledgement that they may be contradicted elsewhere. In his dedication to historical truth Jeremy Gaige has taken on a mighty task. The very least that the rest of us can do is ensure that his findings are noted and given maximum publicity.

(373)

Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, PA, USA) writes:

‘Raymond Keene gives Aron Nimzowitsch, and says that spellings such as Nimzovich and Nimzovitch “are quite simply incorrect” (C.N. 20). I wish I could make flat statements like that, but I am deterred by 20 years of research. In the present case, it could be argued that his correct name is Nimcovičs, to give it the spelling of his native Latvia. Furthermore, anyone checking for books by and about that master in English will not find it in card catalogs under Nimzowitsch, but rather under Nimzovich. In fact, in Chess: An Annotated Bibliography, the reader looking for Nimzowitsch is referred to Nimzovich. Mr Keene would have been on firmer ground if he had confined himself to saying that a) most of the master’s playing career was spent in the German-speaking world, and b) Nimzowitsch is the spelling given on his tombstone, and c) for the reader’s guidance, there are variant spellings. There is usually an ethno-centric bias in such matters, e.g. Wilhelm Steinitz in German sources, William Steinitz in sources in the USA, where he died. It is surely more useful to lay the evidence before the reader and let him judge for himself rather than rapping him on the knuckles.’

(450)

Jeremy Gaige tells us of yet another project that he is undertaking:

‘I have been supplying the John G. White Department of the Cleveland Public Library with namecards – 100% rag paper catalog cards with full name, date and place of birth and death plus bibliographical citations. I have been doing so nation-by-nation as data become reasonably complete. So far, Cleveland has cards for the USA, Britain (England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and any further subdivisions thereof – has Northumbria risen yet?), Hungary, Italy, Canada, Germany and Australia. In all, probably more than 5,000 namecards – which I update for Cleveland so the lists are kept current and corrections, inevitable corrections, are sent about monthly. As you know, all too often some mad eccentric spends a lifetime collecting such material which then dies with the collector. I am determined that the material shall be on permanent file and available to all.’

(535)

From Paul Buswell (Hastings, England):

‘Mr Gaige’s well-known penchant for perfection permits him nevertheless to perpetrate the howler of regarding Ireland as a subdivision of Britain.’

Mr Gaige writes:

‘In C.N. 571, Paul Buswell accuses me of perpetrating “the howler of regarding Ireland as a subdivision of Britain”. Well, wasn’t it? Is it really too unreasonable to suppose that a chess historian (writing to a magazine devoted to chess history) might be referring to past as well as present and future subdivisions? Or is it obligatory to send a potted history of a nation beforehand in order not to be accused of a howler? (If Mr Buswell discovers that the first Israeli Chess Championship was held in 1936, I wonder if he will accuse the Israel Chess Federation of a howler.)

For all this tempest in a teapot, a genuine historical problem arises, something I touched on about the first name of Steinitz, depending on one’s national bias. One aspect of the problem can be considered by taking Mr Buswell at his word. Should a Catalog of British Chess Personalia:

– exclude all Irish, even if they were alive when Ireland was part of Great Britain?

– include only those Irish who ceased playing (or, perhaps, who died) before Ireland became independent, etc.?

– and any other variations that strike one’s fancy.

Readers might care to consider another howler I have been accused of by an atypically dogmatic German colleague: when referring to, say, the birth of a chessplayer in Warsaw in 1942, I have been told that giving Poland as the nation is GANZ FALSCH! because Warsaw was part of Grossdeutschland at the time, ditto Vienna. (Needless to say, I refrained from asking him about Oslo, Amsterdam and Paris.)

In referring, for example, to the Marienbad tournament of 1925, which is the howler?

– To say Marienbad, which did not “exist” in 1925 but which is almost universally given in the chess literature?

– To say Mariánské Lázně, which did exist in 1925, but which is apt to confuse, at least initially, most chessplayers?

I have been criticized, with more justice, for giving, say, Cologne, BRD (West Germany) as the nation of birth for someone born in 1860. When I ask what nation it should be, I am told, “why, Germany, of course”. At that I give up since Germany did not exist (juridically) until 1871. Such critics fail to realize that to give a German’s proper “nation” of birth before 1871 would require keeping track almost day by day of the boundaries of a multiplicity of duchies, principalities, free states, etc. I use present-day national boundaries simply to enable myself and others to know readily which nation to write to for further information.’

(604)

Addition on 5 August 2024:

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘Jeremy Gaige wrote rhetorically above:

“Or is it obligatory to send a potted history of a nation beforehand in order not to be accused of a howler? (If Mr Buswell discovers that the first Israeli Chess Championship was held in 1936, I wonder if he will accuse the Israel Chess Federation of a howler.)”

Jeremy Gaige was certainly correct that he could not be expected to provide such a history, and that it is no “howler” to refer collectively to the championships in pre-independence Mandatory Palestine and post-independence Israel as the “Israeli” championships. But, for once, he is wrong on a point of detail. The Israeli Chess Federation never referred to the 1936 championship as the “first Israeli chess championship”. Rather, it referred to it as the first championship of Erez Israel – “the land of Israel” – the Hebrew name for the territory known in English at the time as “Palestine”.’

The untiring Jeremy Gaige has begun ‘an informal and occasional newsletter designed to enable chess historians to pool and share their findings’, the first issue now being available. We are grateful for a generous reference to Chess Notes as ‘a treasure trove for chess historians’.

No charge is made for the Chess Historian, but any applicants for copies to Mr Gaige should indicate those areas in which they might be able to help in the onward march towards chess truth.

(603)

August 1984 brought two further issues of Jeremy Gaige’s newsletter, the Chess Historian. One is a ‘Report to Colleagues’ on how his work is progressing. A fourth edition of the Catalog ("Chess Personalia’) is expected to be completed before the end of the year, while J.G. plans to publish Volume V (1931-50) of Chess Tournament Crosstables by the end of next. We read with awe that his computer recently totted up the number of crosstables (excluding many Swiss-system events) in his collection: 10,500. Issue 3 of the Chess Historian is a depressing account of the difficulties encountered by Mr Gaige when trying to help make FIDE’s International Rating List as complete and accurate as possible.

(818)

Issue 4 (June 1985) of Jeremy Gaige’s the Chess Historian announces that the first volume of Chess Tournaments, A Checklist (covering the period 1851-1950) will be available shortly in a commercially printed edition at $12.50. For anyone truly interested in chess history it will be an essential working tool.

(1039)

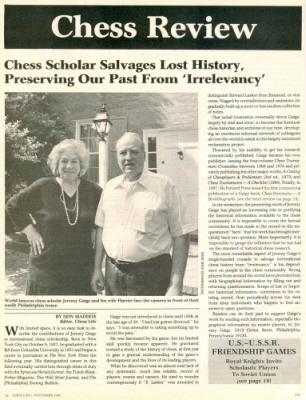

A feature about Jeremy Gaige by Don Maddox was published on pages 12-13 of the November 1988 Chess Life:

Some corrections from Gaige were given on page 7 of the February 1989 issue of Chess Life.

From Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, PA, USA):

‘While putting Chess Tournament Crosstables (1849-1914, so far) in my computer, I keep coming across a J.M. Lee fl. Paris c1890-1920. I would like to know a little more about him, at least his first name.’

(1610)

In his privately circulated 1994 edition of Chess Personalia, A Biobibliography, there was an entry for ‘James M. Lee fl. c1895-1915 in Paris, FRA’.

Lee is mentioned in our feature article E.M. Antoniadi.

The last paragraph of C.N. 1782:

Within a few minutes of coming across the above game we were able to construct a detailed picture of John Edmund Hall (1853-1941) simply by following up the references in Chess Personalia. Without Gaige’s book, this would have been impossible.

(1782)

C.N. 1491 reviewed Chess Personalia, A Biobibliography, a remarkable book by Jeremy Gaige which presented essential biographical data on about 14,000 chess personalities of all nations and periods and which won the 1987 C.N. Book of the Year award. We are delighted to learn from Mr Gaige that in 1997 the publishers, McFarland & Company, Inc., will be bringing out a second edition. Updating the book is a monumental task, and Mr Gaige would welcome assistance, not least in tracking down obituaries of a number of lesser-known masters and other figures who have died in recent years. Specific information, or indeed a general offer of help with research, should be sent as soon as possible to Jeremy Gaige.

(2135)

Such is Jeremy Gaige’s standing among chess cognoscenti that a lesser light may be eager somehow to out-Gaige him. G. Di Felice’s Preface to Chess Results, 1747-1900 states that the book contains more crosstables than Gaige’s Chess Tournament Crosstables, Volume 1 (Philadelphia, 1969) and so it does, but, of course, after 1969 Gaige continued to add to his archives, and at a remarkable rate. In 1984 he brought out a book of which Di Felice shows no awareness, Chess Tournaments A Checklist Vol. I 1851-1950. Tournaments for which Gaige then possessed the crosstable were marked in the checklist with an asterisk, and their number far exceeds those included in Di Felice’s book some two decades later. A sequel by Gaige, also published in 1984, dealt with tournaments from 1951 to 1980.

It is on his crosstables project (four volumes) and Chess Personalia A Biobibliography (Jefferson, 1987) that his reputation is founded and will endure, but there has been much else. Our collection contains, for instance, a 1985 revised edition of the first Checklist book, as well as seven bound versions of his Index of Obituaries in the British Chess Magazine, a 1994 edition of Chess Personalia and such volumes as FIDE-Titled Correspondence Players (1985), A Catalog of British Chess Personalia (1985), Catalog of USA Chess Composers (1987), Swiss Chess Personalia (1987), FIDE Female Titleholders (1991) and USA FIDE-Titled Players & Arbiters (1993).

On pages 58-60 of the 8/1987 New in Chess we wrote an appreciation of Jeremy Gaige’s unique contribution to chess scholarship. John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) informs us that in 2004 he unavailingly nominated Gaige (and Walter Penn Shipley) for the USCF’s Hall of Fame. Our own view is that halls of fame and other soi disant achievement awards are embarrassingly nugatory (would Gaige really have his status enhanced as an ‘inductee’, alongside writers like Fred Reinfeld and Al Horowitz?), but if such conferrals must exist there is no US chess figure more deserving than Gaige. In any case, we agree with every word written by Dr Hilbert in his nomination submission, which is reproduced below with his permission:

‘As anyone who has tried to do serious work in chess history knows, such work would, in large measure, not be possible without Gaige’s extensive contributions. His four volume Chess Tournament Crosstables remains the standard for the period 1851-1930. Even more importantly, his monumental Chess Personalia, with over 14,000 bibliographical entries listing essentially every major chess player for the past 200 years or more, is the bible for anyone wishing to work on the history of the game. I’ve published eight books on chess history, biography, and tournament play in the past eight years, and in all honesty can say I would not have attempted to write any of them were it not for the extraordinary work Jeremy Gaige has performed. His kindness and help, both personally and in his essential writings, have been appreciated by dozens of chess scholars world-wide for decades, and his writings will be the standard in the field for many generations to come. Anyone interested in the history of our game owes him a debt that cannot adequately be calculated, let alone repaid.’

(3595)

Jeremy Gaige informs us that he is seeking the contact details of collectors who are interested in acquiring the archives which he has built up over the past 40 years. We shall gladly forward to Mr Gaige any enquiries from prospective purchasers, whether individual or corporate, of his unique collection of material.

(5522)

Marking the recent death of Jeremy Gaige, we reproduce C.N. 1491, which concerned his book Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987):

About 14,000 chess personalities past and present are featured in this awe-inspiring book. From Erkki Aaltio to Adolf Zytogorski, each entry aims to give the date and place of birth and, where appropriate, death. A selection of newspaper, magazine and book sources is cited, as are FIDE titles, Elo historical ratings, etc. To take one entry at random:

‘Bogoljubow, Efim Dimitrijewitsch

born: 14 April 1889 Stanislavitsk/Kiev, USSR

died: 18 June 1952 Triberg, Federal Republic of Germany

GM 1951

Elo Historical Rating: 2610

American Chess Bulletin, 1952, page 72

British Chess Magazine, 1952, pages 253-254

Caissa, 1952, pages 133-134

Chess Pie No. l, 1922, pages 8-10

Chess Review, 1952, page 200

Chess Career of E.D. Bogoljubow by Jack Spence

Deutsche Schachzeitung, 1952, pages 224-225

Deutsche Schachblätter, 1952, pages 115-116

Grossmeister Bogoljubow by Alfred Brinckmann

Teplitz-Schönau 1922, pages 567-568.’His date of birth is marked to indicate that it has been converted to the Gregorian Calendar (New Style).

As an indication of the vast scope of the book: how many chessplayers whose surnames begin with Z could the average enthusiast recite? Gaige lists over 250.

The value of such data is enormous, and the book is particularly valuable for the details it provides on relatively minor figures. If the reader wishes to know the exact date and place of death of Henry Grob (of 1 g4 fame), it is unlikely that he will find the correct information anywhere other than in Chess Personalia (3 July 1974, at Zollikon, Switzerland, the source of this information being Stadtarchiv Zurich). In countless cases the entrants themselves, or their next of kin, have been contacted for authoritative biographical information. For old players an astonishing array of journals is quoted; for Sarratt we are referred to page 307 of the 1819 Bell’s Weekly Messenger and the 14 November 1819 issue of the London Observer.

Chess Personalia is a brilliant achievement. It will prove indispensable not just to historians and journalists but also to clubs, federations, libraries and players, composers, etc. There are precious few books which we would recommend to our readers as indispensable, but Chess Personalia is definitely one of them.

That Jeremy Gaige finds the time and energy for so much high-quality research is almost miraculous; he stands supreme as chess’s greatest ever archivist.

On 12 March 2011 we placed on record at ChessBase Gaige’s ‘self-obituary’, which he sent us for safe keeping in 1988.

(6997)

The item referred to above:

The Philadelphia Inquirer of 10 March 2011 reported that Jeremy Gaige died on 19 February 2011, at the age of 83. The present article does not repeat our own assessment of his unique contribution to chess history, including Chess Personalia. Instead, we simply place on record, for the first time, Gaige’s own ‘obituary’ of himself. Over the years the two of us exchanged countless letters and documents, and in March 1988 he spontaneously sent us a 1,500-word article with the following note:

‘For your files: I am not contemplating your publishing this material as such (except as an obituary ... not for a while, I hope). J.G.’

The complete text written by Gaige is given below without comment:

‘Gaige, Jeremy (1927- ) Chess historian and archivist was born in New York City on 9 October 1927, the son of the late Crosby Gaige, widely known in his day as a theatrical producer. Jeremy was educated in public schools and prepared for college at Phillips Academy, Andover, in the class of 1945. After serving with no special distinction in the US Army Medical Corps, Gaige matriculated at the College of Columbia University (BA 1951). Characteristically, he excelled in the courses he enjoyed – history, political science and related subjects; similarly he performed lamentably in subjects he disliked. (It took him four years to complete the required two years’ study of a foreign language.) He graduated in 1951 and was married the same year to Elise Cookson. In the following year, he began a journalistic career as a copyboy at the New York Times, a position which enabled him, remarkably, to write editorials as well as fill pastepots for that paper. In 1953, he joined the Syracuse Herald-Journal, where he was a general assignment reporter, feature writer and radio/television columnist. In 1955, he joined the Toledo Blade as an editorial writer. In 1956, while being divorced, he returned to New York City, where he was a writer at Forbes magazine and later at the Wall Street Journal.

In 1958, he married Harriet Elizabeth Oken and joined the financial news department of the (Philadelphia) Evening Bulletin, where he worked in a variety of capacities and was day telegraph editor when the paper ceased publication on 29 January 1982 (his wife’s birthday). Since then, Gaige worked in a variety of positions related to journalism, most recently (1 February 1988) as a speechwriter for a major pharmaceutical manufacturing company. The Gaiges have one daughter, Monica, a graduate of the Philadelphia College of Art, where she majored in graphic design. He was warmly supported in his efforts by his wife and daughter. Of his wife, he said in his introduction to Vol. IV of Chess Tournament Crosstables, “She has let me be what I want to be and do what I want to do; I could wish no man any greater felicity.”

Although Gaige was highly respected by his peers as a journalist, he achieved far greater distinction as a chess historian and archivist. In 1958, after his divorce from his first wife, he was introduced to chess at the age of 30. He found the game itself fascinating, but his limited skill became quickly apparent. As foreshadowed by his college years, his true metier was the temporal-historical rather than the spatio-mathematical; and, as also foreshadowed, he liked best what he did best. It was therefore with a certain sense of inevitability that he gravitated to a study of the history of chess. In the beginning, it was simply to gain a general understanding of the game’s development and of the lives of its leading practitioners.

He soon found that, in the late 1950s, there was virtually no concentrated material. Murray’s great work, A History of Chess, in effect ended just when international tournaments were beginning. And the more he looked, the more he discovered an almost total lack of any systematic, much less reliable, record of players, their match and tournament records, national championships, and even first names. He used to contemptuously wonder if “E. Lasker” was intended to distinguish Edward Lasker from Emanuel, or vice versa. In short, all those records which form a routine part of other sports, whether it be baseball, cricket, boxing or football. He gradually built up a more or less random collection of notes. But, as many a researcher has found, his own investigations disclosed more questions than answers. (Gaige’s own definition of an expert was “someone who is aware of how little he knows”.) This, in turn, disclosed more contradictions and still more questions.

But gradually, some answers also began to emerge along with Gaige’s skill as a researcher which he acquired largely by trial and error. His approach was described in the appendix of his Catalog of USA Chess Personalia. A case in point: By all accounts (such as A Sketchbook of American Chess Problemists, Vol. I , page 6), Charles Henry Stanley died in New York City on 16 March 1894. Gaige’s increasingly systematized research found that was the approximate date of death in England of a Henry Stanley, not of Charles Henry Stanley. A painstaking search through New York City’s records of death showed that Stanley did not die there before 1900. Examination of the 1900 US Census Report showed an 80-year-old Charles H. Stanley living in New York City at the time. From there, it was simple enough to find the date of death but not, unfortunately, the exact date of birth. (A full account is given in the BCM, 1982, pages 364-367.)

So far (1988), Gaige’s chief publication has been four volumes of Chess Tournament Crosstables. Vol. I, issued in 1969 covered 1851-1900; Vol. II, issued in 1971, covered 1901-10; Vol. III, issued in 1972, covered 1911-20; and Vol. IV, issued in 1974, covered 1921-30. The Oxford Companion to Chess called these volumes “the standard reference work”. (By the second quarter of 1988 [sic], Gaige had put in his computer a complete revision of crosstables from 1849 through 1914, and was hoping for world enough and time to a) get through to 1950, and b) see the commercial publication of his life’s work.) Gaige’s other major works include A Catalog of Chessplayers & Problemists, 3rd ed., 1973; and Chess Tournaments – A Checklist, 1984. By late 1986, Gaige had virtually completed a biobibliography of chess personalia consisting of more than 14,000 entries giving (to the extent available) full name, date and place of birth and death, FIDE title and bibliographical sources.

He has also issued numerous monographs to colleagues “to help you and to help you to help me”, as he put it. In the course of such mutually beneficial exchanges, or lack of exchanges to those he considered freeloaders, Gaige was considered generous or selfish. Similarly, he was praised for citing the works of others and freely confessing his own uncertainties about specific data. But Gaige himself preferred to think in terms of what would best enhance the obtaining, compiling, verifying and disseminating of such information. For example, he has typed on 100% rag paper library catalog cards more than 5,000 biobibliographical entries which he gave to the Cleveland Public Library chess archives. The library, in turn, generously helped him. Perhaps his one vanity was having his works cited in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. (“My vanity is no greater or less than any other man’s, it’s just that I have a higher threshold. Some enjoy having a low-number license plate or the key to the executive washroom; I enjoy being cited in the EB.” It was, perhaps, an astringent lesson that even this glory was transitory when subsequent editions of the EB severely curtailed its article on chess, eliminating the bibliography.) But for the most part, his life was guided by the belief that the work is everything, the man is nothing – “to a large extent”, he would qualify. And whatever notice he received was viewed largely in terms of its ability to enhance his work.

Extrinsically, Gaige’s efforts had been sorely limited by his inability to get his works commercially published and into the hands of a wider audience. But 1987 saw the publication of one of his major works: Chess Personalia – A Biobibliography. (Here, again, Gaige had ample opportunity to savor his taste for irony: laudatory reviews [see, especially, New in Chess, #8, 1987, pages 58-60] and minuscule sales.)

Intrinsically, his strengths combined those of journalist and historian – insatiable curiosity, persistence, an eye for contradictory data, and considerable though by no means invariable skill in determining the correct version. His weaknesses included his limited skill at the game of chess itself, the historian’s sometimes debilitating sense of irony (“I’m obsessed by the futility of all human endeavor”, he used to say, perhaps thinking of Houseman’s view of human life, “a long fool’s errand to the grave”), and his virtually total ignorance of any language but English (“I’m fluently illiterate in at least 14 foreign languages”, he used to say in typical self-deprecation).

He was also chary of making value judgments, again the legacy of his historian’s view, i.e. “history has seen the death of many fighting faiths”, citing Justice Holmes. But he was often scathing in criticizing what he considered the erroneous value judgments of others, especially if expressed with undue confidence. “The less knowledge, the more certainty”, he would snort.

His long-range goal, “given three or four lifetimes”, was to produce a dictionary of Chess and Chess Personalia comparable to Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Failing that, his own hope was that his efforts, which he was at pains to define as the latest word, not the last word, would provide a reliable basis of received knowledge to enable future historians to create such a dictionary.’

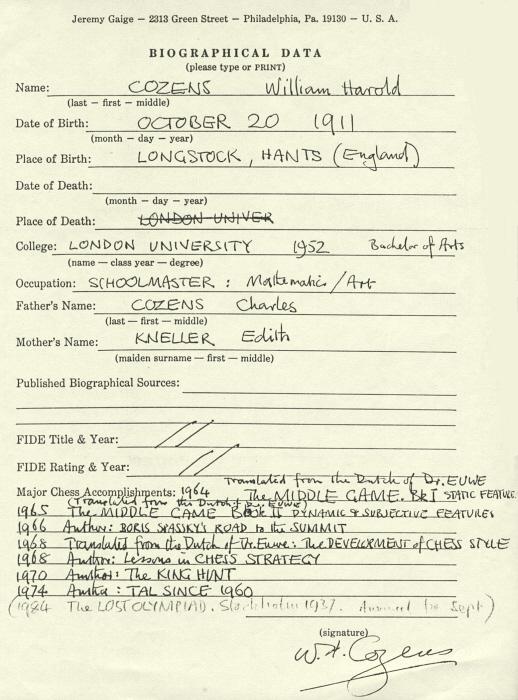

Jeremy Gaige gathered much data with a biographical form circulated to chess personalia. By way of example, below is the sheet completed by W.H. Cozens:

The information about his parents has taken us to the remarkable Cozensweb site, which gives many further details.

See also C.N. 3183 in The Chess Writer W.H. Cozens.

(6998)

A very early chess article by Jeremy Gaige was ‘The Ethics of Chess’, on page 106 of the April 1961 Chess Review.

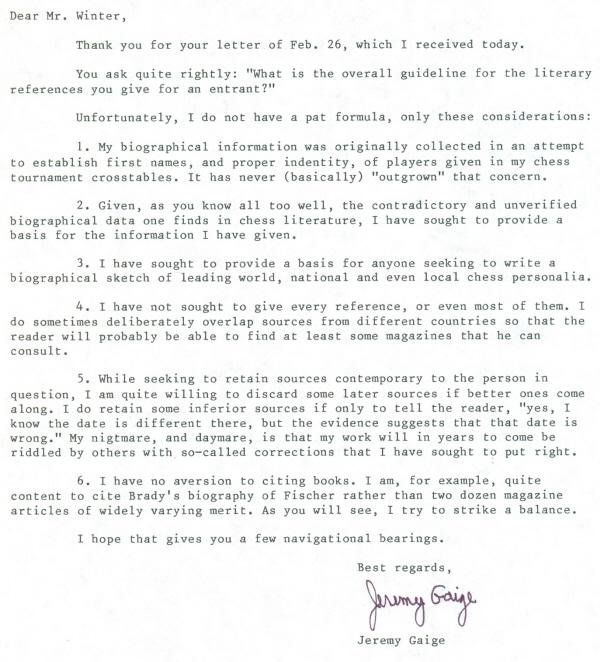

As part of our collaborative work with Gaige during his preparation of Chess Personalia for publication by McFarland, we enquired about his general criteria for including references in the listings. Below is his reply (letter dated 3 March 1986):

If Gaige’s Chess Personalia (1987) were a federation’s project, a sub-committee might still be drafting the terms of reference.

(9555)

Any chess writers tempted to boast – in book publicity material or in a Preface, for instance – that they have found corrections to Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) naturally need to check that the matters were not rectified by Gaige himself in his unpublished 1994 edition.

A number of C.N. items have cited this privately printed, 860-page revised, updated and expanded edition. Gaige’s Introduction stated that there were ‘about 15,000 entries’, as opposed to ‘about 14,000 entries’ in the McFarland book (the hardback of 30 years ago and the subsequent, unaltered paperback).

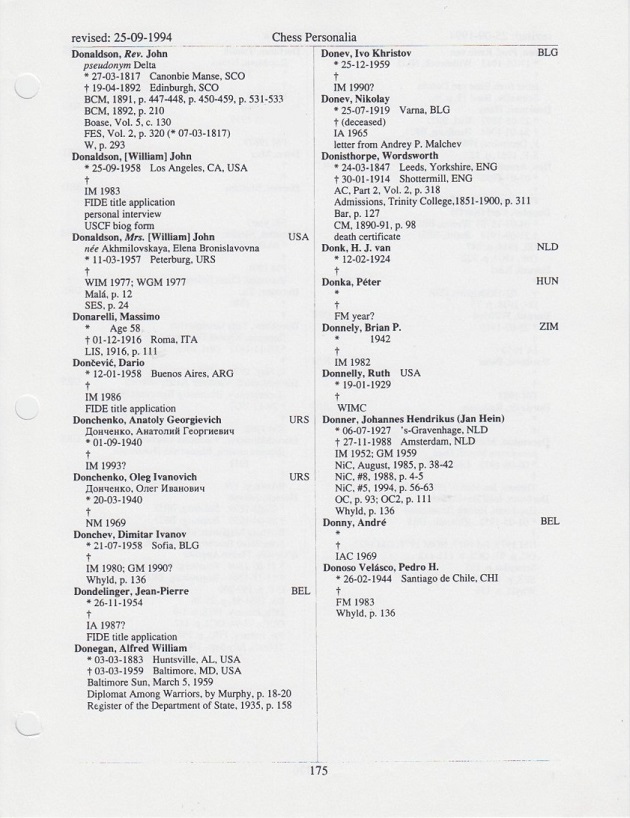

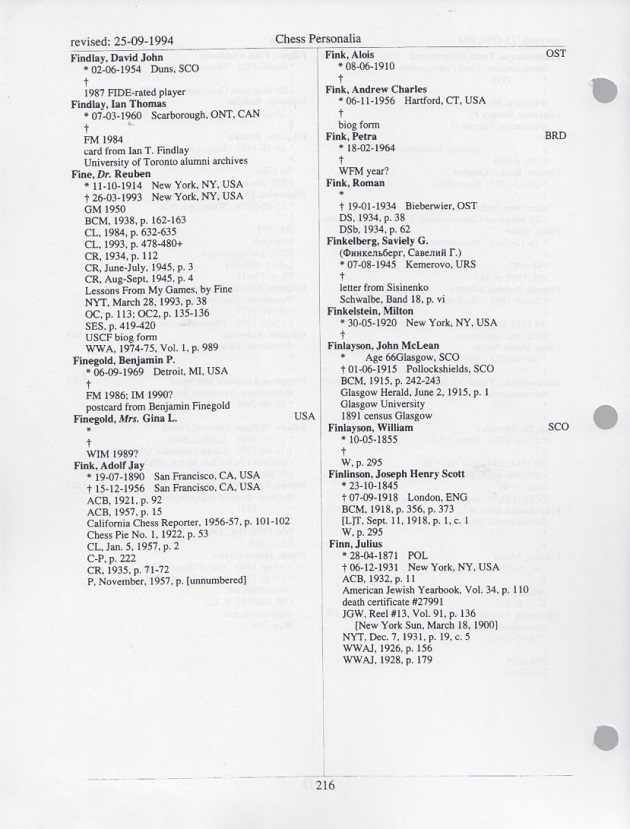

Below are two illustrative pages from the 1994 edition (featuring, for example, the entries on Donner and Fine):

(10526)

As a matter of common sense, fair play and respect for the late Jeremy Gaige, the privately distributed 1994 edition of Chess Personalia (860 pages), referred to in C.N. many times, should obviously be taken into account by anyone presuming to make corrections or additions to the 1987 McFarland edition.

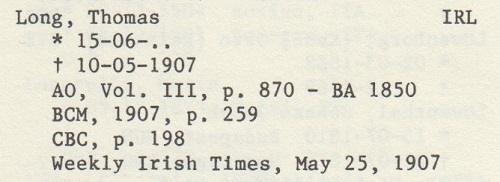

Our second dip into British Chess Literature to 1914 by Tim Harding (the first was in C.N. 10815) concerns the section ‘Some Amendments to Gaige’s Chess Personalia’ on pages 349-352. The sourceless ‘amendments’ offered by Harding may correspond to information already presented by Gaige himself in the 1994 edition, and Thomas Long will serve as an example. From Gaige’s 1987 book:

Harding, on page 351, gives an ‘amendment’ (i.e. the addition of Long’s year of birth, and his place of birth and death):

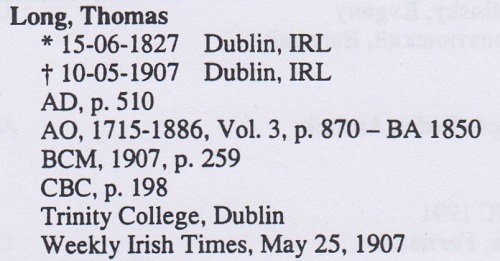

However, all that information was included by Gaige 24 years ago:

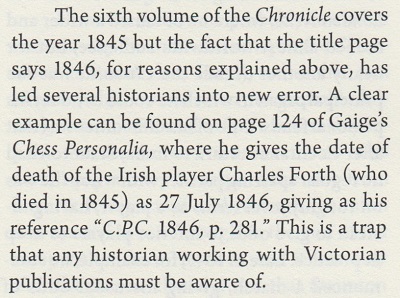

There are also corrections of Gaige elsewhere in Harding’s book, as on page 199:

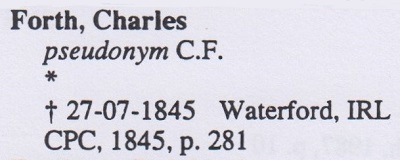

That matter too was corrected by Gaige 24 years ago:

(10831)

[On the specific case of Forth, see our addition of 8 November 2023 below.]

Chess Personalia A Biobibliography by Jeremy Gaige was published by McFarland & Company, Inc. in 1987, and a paperback reprint was issued in 2005. Gaige died in 2011.

The paperback edition corrected a large number of typographical errors in the Introduction but had no updating of the biobibliographical entries, even though Gaige had continued to add information to his archives, and notably in an 860-page revised, updated and expanded edition privately circulated in 1994.

Robert Franklin (Jefferson, NC, USA), the former President of McFarland whose title is now Founder and Editor-in-Chief, informs us that when the company issued the paperback it was unaware that an updated version existed:

‘We have never received a copy. We did not learn of its existence until years later. He did not have the legal right to publish the revision (because he had signed over to us, routinely, as with all McFarland authors, the rights to the book and the title, so it took us aback a bit when we learned). We did nothing about it and treated his widow with great care and respect after his death. We would certainly have considered a revised edition if he had approached us about it.’

Concerning C.N. 10831, on Tim Harding’s recent list of amendments to Chess Personalia, Mr Franklin writes:

‘The complaint is faulty that Tim Harding should have known the 1987 book had already had revisions “privately distributed” and therefore should not have gone to the trouble of offering amendments to same in his British Chess Literature to 1914 (McFarland, 2018). The crux of the matter is: Who has access to the 1994 “edition”? If the legal owner of the item (!) has never seen one, and a senior ranking, very sober-minded chess author is not aware of it, one begins to think that the corrections offered by Mr Harding are in fact useful at least to those who were not sent a copy in 1994.’

It is not a question of whether or not Tim Harding’s amendments are useful. The issue is the fairness and respect due to Jeremy Gaige. We already made the point in July 2017 (C.N. 10526):

Any chess writers tempted to boast – in book publicity material or in a Preface, for instance – that they have found corrections to Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) naturally need to check that the matters were not rectified by Gaige himself in his unpublished 1994 edition.

Throughout his life, Gaige circulated private editions of his works to researchers who might be able to assist him, and it is self-evident that he did not cease updating Chess Personalia after the book was published in 1987.

That leaves Mr Franklin’s comments about whether Harding should have known about the privately distributed edition. It has been referred to in C.N.s 2799 (posted in 2002 and reproduced on page 153 of our McFarland book Chess Facts and Fables), 3595, 4398, 4579, 4609, 4661 4836, 4982, 5112, 5115, 6975, 7054, 7774, 7854, 8677, 8831, 8945, 9034, 9086, 9135, 9193, 9612, 9668, 9680, 9727, 9773, 9845, 10120, 10156, 10357, 10526, 10680 and 10804.

(10861)

Addition on 8 November 2023:

Readers are invited to decide how C.N. 10861 (concerning Timothy Harding’s alleged unawareness of the privately circulated 1994 edition of Chess Personalia) can be reconciled with the following.

Firstly, the text of C.N. 4384:

From Tim Harding (Dublin):

‘He was indeed George William (and not Williams) Lyttelton, as is shown by all the regular (i.e. non-chess) reference works (such as Cokayne’s Complete Peerage, Burke’s, Debrett’s, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Alumni Cantab). I have no idea how Gaige made his mistake.’

We now note that in the 1994 (privately circulated) edition of Chess Personalia Jeremy Gaige amended ‘Williams’ to ‘William’.

After we sent Harding the courtesy of a preview of the above C.N. item on 4 June 2006, he wrote to us the same day:

‘Your text below sounds OK to me. I did see the private version of Gaige when I was in the Royal Dutch Library last September but I cannot remember if I checked that detail about Lyttelton. I had so much else to do.

If you want to pursue Gaige in CCN [sic], here is a suggestion.

See page 124. Forth, Charles.

(If you have regular access to the 1994 version please check this as I would be interested to know if Gaige fixed it.)

He died in 1845 not 1846. I have not found out yet when he was born.

Gaige cites “CPC 1846, p. 281” but he means volume 6, which was published during 1845, only the title page has 1846 on it. As you no doubt know, for several volumes the year in bound volumes of CPC is misleading in this way and Gaige was caught out.

So the question for your readers is whether this is a systematic error in Gaige that is repeated for other entries where he relied on CPC volume 6 and other early volumes of CPC. If so, we need to compile a list of all the people for whom he is a year out because of this mistake.

Or did you do this topic already?’

On 6 June 2006 we told Harding:

I was aware of the confusion over the dating of the Chronicle, and I can report that in the Forth entry in the 1994 edition of Chess Personalia ‘1846’ was twice amended to ‘1845’.

To which Harding replied on the same day:

‘Thank you for checking that for me. I’m glad to hear Gaige got it right in the end and will amend my footnote accordingly.’

In short, any suggestion that Harding was unaware of the 1994 privately circulated edition of Gaige’s book is false. We discussed it with him, and he told us in 2006 that he had seen a copy himself, at the Royal Dutch Library.

For more on the conduct of Timothy Harding, see our feature article on him.

Some observations by Jeremy Gaige on page 3 of his booklet A Catalog of U.S.A. Chess Personalia (Worcester, 1980):

(11431)

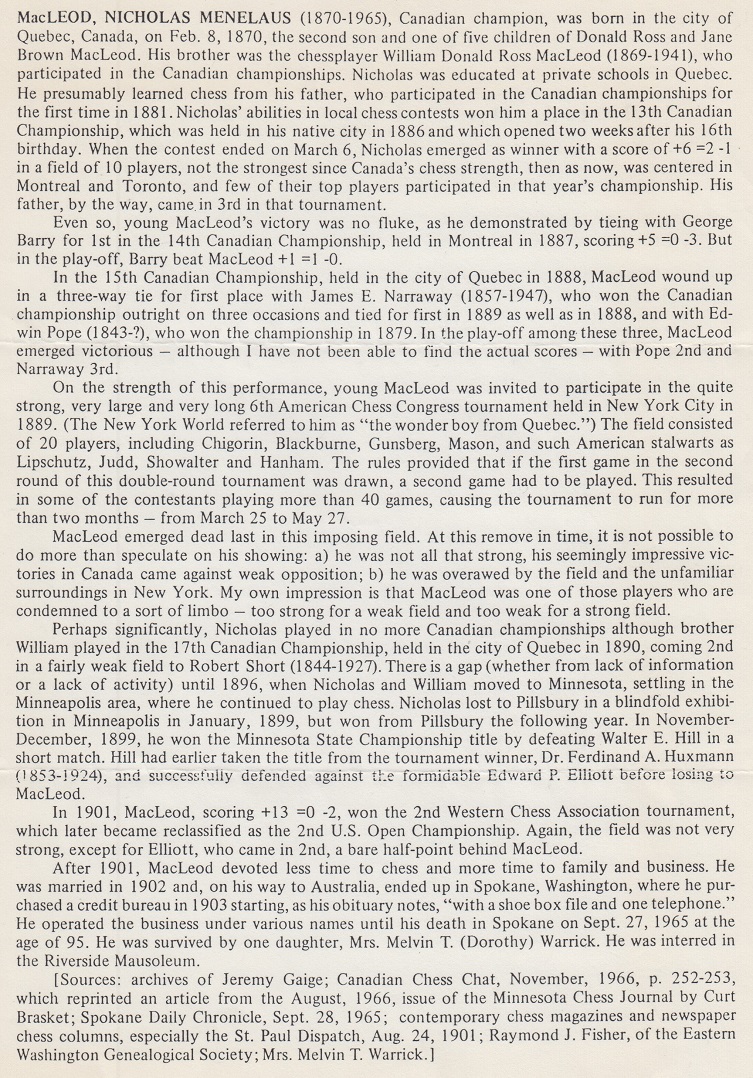

Below is a potted biography of Nicholas Menelaus MacLeod which Jeremy Gaige sent us in 1983. As mentioned on page 257 of Chess Explorations, it was reproduced in C.N. 479.

Concerning C.N.’s discussion of Janowsky and Tartakower spelling matters, see the sequence beginning with C.N. 1342 in Chess Jottings. Jeremy Gaige made a number of remarks about Tartakower’s forename and surname.

Addition on 24 October 2024:

Nearly 34 years on, we show some observations by Jeremy Gaige about Kenneth Whyld, in an extract from a private letter sent to us on 5 November 1990:

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.