Edward Winter

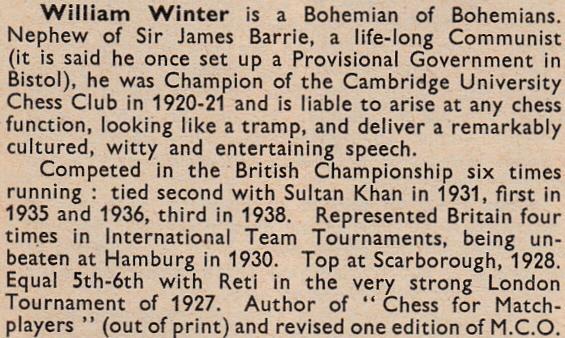

William Winter (C.N. 4356)

The present article comprises a number of C.N. items about William Winter. See the Factfinder for references to further material.

In C.N. 1072 William Hartston quoted from the Evening News (London), 5 December 1921 regarding a court case in which William Winter was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for seditious speeches. See pages 124-125 of Chess Explorations and Chess in the Courts.

A selection of quotes from William Winter’s posthumous memoirs, which were published in CHESS between 29 October 1962 and 28 March 1963:

R.H.V. Scott: ‘Probably the most brilliant combinative player England has ever seen.’ (page 32)

‘[Emanuel Lasker] before any tournament made a careful study of the weaknesses of each of his opponents, both as regards style of play and temperament. It is entirely legitimate, and can prove very useful until one comes up against an opponent like Capablanca who had no weaknesses of any kind.’ (page 75)

Burn: ‘One of the kindest as well as the strongest of chess masters.’ (page 108)

‘Blindfold play I have never attempted seriously. I once played six, but spent so many sleepless nights trying to drive the positions out of my head that I gave it up.’ (page 110)

‘It is hardly believable that a paper like The Times, which justly prides itself as being represented by the best available talent in all forms of human activity, should hand over its chess, both in the main paper and the subsidiary supplements, to a man to whom any first class chessplayer could give a rook. Yet it is absolutely true. This man, Tinsley by name, was the son of a minor professional who represented the paper fairly satisfactorily in the beginning of the century. When he died of a sudden stroke his son went to The Times office with the news, and offered to carry on for a week or so until a successor could be appointed. He carried on for nearly [sic] 30 years! Uncouth and almost uneducated, he made The Times reports a laughing stock all over the chessplaying world, but, by a mixture of bluff and bluster, maintained his position until his own death in 1936.’ (page 111 ) (In fact Tinsley died in 1937.)

Yates: ‘One of the most talented chessplayers as well as one of the finest men I have ever met.’ (page 147)

Hooper: ‘He is one of the most thorough and conscientious analysts I have met.’ (page 151)

(1197)

In his Financial Times column of 30 August 1986, Leonard Barden states that this was the position after Black’s 33rd move in Winter-Capablanca, Nottingham, 1936:

‘Several readers spotted that 1 Q-R5ch wins a rook. Not a misprint – Capablanca’s previous move was R-K7 [from e4] and Alekhine makes no comment in the tournament book. Thus a blunder by two world champions is found some 50 years later.’

In fact, the tournament book inverted Black’s 33rd and 34th moves – there was no opportunity to win a rook. Play went 33...Ng7 34 Qxh7 Re2.

(1252)

Christophe Bouton (Paris) points to the Winter v Capablanca game played in the Hastings tournament of 1919 and asks us, ‘Is that you?’

No. We had retired by then.

(1795)

From page 19 of Chess for Match Players by W. Winter (London, 1951), in a description of the position after 1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 Nf3 Nxe4:

‘Also good for a combinative player is 3…Kt-B3 transposing into the Five Knights’ Defence q.v.’

The error was subsequently corrected (cf the Dover reprint).

(2662)

C.N. 2912 quoted another passage from William Winter’s memoirs, on page 149 of CHESS, 23 February 1963. It concerned Sultan Khan:

‘At the Team Tournament at Hamburg (1930) he also did extremely well on the top board against the best continental opposition though his apparent lack of any intelligible language annoyed some rivals. “What language does your champion speak?”, shouted the Austrian, Kmoch, after his third offer of a draw had been met only with Sultan’s gentle smile. “Chess”, I replied, and so it proved, for in a few moves the Austrian champion had to resign.’

In C.N. 2912 we observed: ‘The problem with this story is that the game between Sultan Khan and Kmoch was drawn.’

Kmoch himself rebutted the anecdote in a letter published on page 245 of CHESS, 25 May 1963:

‘Not that it matters, nor that I would cast any blame on the late Winter, whom I knew as a perfect gentleman. It is only for the sake of curiosity that I ask permission to comment on Winter’s story concerning my game against Sultan Khan.

I never asked Winter or anybody else what language Sultan Khan spoke. Nor did I shout (I never do). Sultan Khan and I had met before. What little conversation there was between us was done in English, of which we both had a command sufficient for the purpose.

Winter, being not asked, had no opportunity to reply “Chess” or anything else.

I did not offer a draw three times, nor did Sultan Khan, who never smiled, meet my offers with a smile. Nor again did I resign a few moves later. And I was not the Austrian champion (contests have not been held at all in my active time).

Sultan Khan had White; we played a Giuoco Piano. After a small number of moves, probably 18 or so, a position was reached which I considered as fully satisfactory for Black.

I offered a draw so as to gain time for my work as a reporter. (I used to be very strict in never offering a draw to anybody unless my position, to the best of my understanding, was fully satisfactory.)

Sultan Khan accepted my offer outright. The game’s ending in a draw is a provable fact.’

(3960)

In an article on page 195 of the September 1971 Chess Digest Magazine William Winter was given the Koltanowski treatment:

‘Winter was a heavy drinker and one of the best chess stories I know is the one of the committee that was formed in 1927 just before the International tournament was to take place in London. They raised one hundred pounds (about 350 dollars then) to support William Winter, so that he could win the event with great ease. In the first round William Winter came into the playing hall, breathing harshly and he beat the great Richard Reti. The next day, Winter weaved into the playing room, sat down at his board and beat the perplexed Aron Nimzowitch. The third day Winter staggered to his seat and beat my co-patriot, Edgar[d] Colle. It looked like it was going to be a big triumph for British Chess. But the expectations were short-lived. Winter had spent all the raised funds on booze in the first three days, and the so-called Winter Committee couldn’t raise another penny from its supporters. The first prize was only one hundred pounds! William Winter arrived sober for each round after the third and lost every game.’

Let us, firstly, compare the above with the complete record of the tournament given in M.A. Lachaga’s comprehensive book on the event, published in 1968. William Winter’s round-by-round performance was as follows:

1: lost to Fairhurst

2: beat Buerger

3: beat Thomas

4: drew with Marshall

5: lost to Bogoljubow

6: drew with Yates

7: lost to Tartakower

8: beat Nimzowitsch

9: drew with Colle

10: lost to Réti

11: beat Vidmar.

This placed him among the prize-winners, i.e. equal sixth with Réti. He did not defeat Réti or Colle; nor did he play in the first three rounds any of the masters named by Koltanowski. About the alleged ‘Committee’, we know nothing, but it may be wondered who would put together £100, or any other sum, so that W.W. could win ‘with great ease’ a tournament which included Bogoljubow, Marshall, Nimzowitsch, Réti, Tartakower and Vidmar. Moreover, £100 (the amount which, Koltanowski alleges, was spent on alcohol consumption within three days) was then roughly $500, not $350. In today’s money it would come to over $5,000. Finally, the first prize in the tournament was not £100 but £50 (BCM, August 1927, page 335).

Thus every verifiable ‘fact’ in Koltanowski’s yarn is false. Why? Was he guilty, once more, of ‘mere’ sloppiness and doltishness (page 341 of the September 1922 BCM was certainly inspired when it spelt his name ‘Klotanowski’) or was there also a darker side to his compulsive fabrications? William Winter was indeed known to drink heavily, but what sort of human being would, in ‘one of the best chess stories I know’, publicly ridicule a deceased master for alcoholism without making the remotest effort to be truthful?

William Winter

(3624)

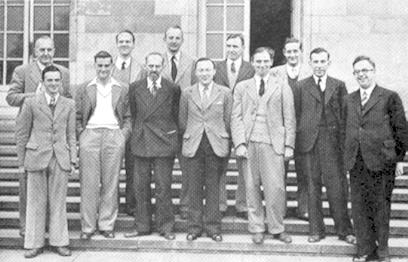

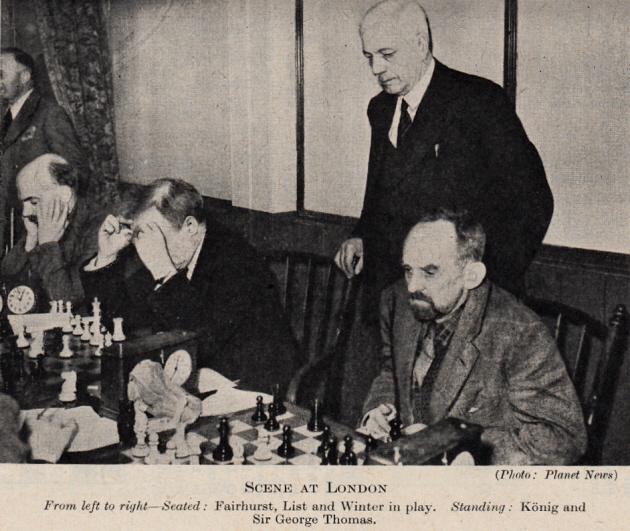

This group photograph from London, 1927 suggests that William Winter, seated second from the left, was (unless exceptionally long-legged) a small man:

Seated from left to right: F.J.

Marshall, W. Winter, E. Bogoljubow, A. Nimzowitsch, W.A.

Fairhurst, S. Tartakower.

Standing: W.H. Watts, M.E. Goldstein, H. Kmoch, M. Vidmar, R.C.

Griffith, Sir George Thomas, E. Busvine, F.D. Yates, J. Schumer,

E. Colle, V. Buerger, R. Réti

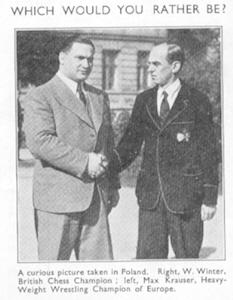

On the other hand, C.N. 2819 reproduced from page 107 of CHESS, 14 November 1935 the following picture:

The caption below the photograph reads: ‘A curious picture taken in Poland. Right, W. Winter, British Chess Champion; left, Max Krauser, Heavyweight Wrestling Champion of Europe.’

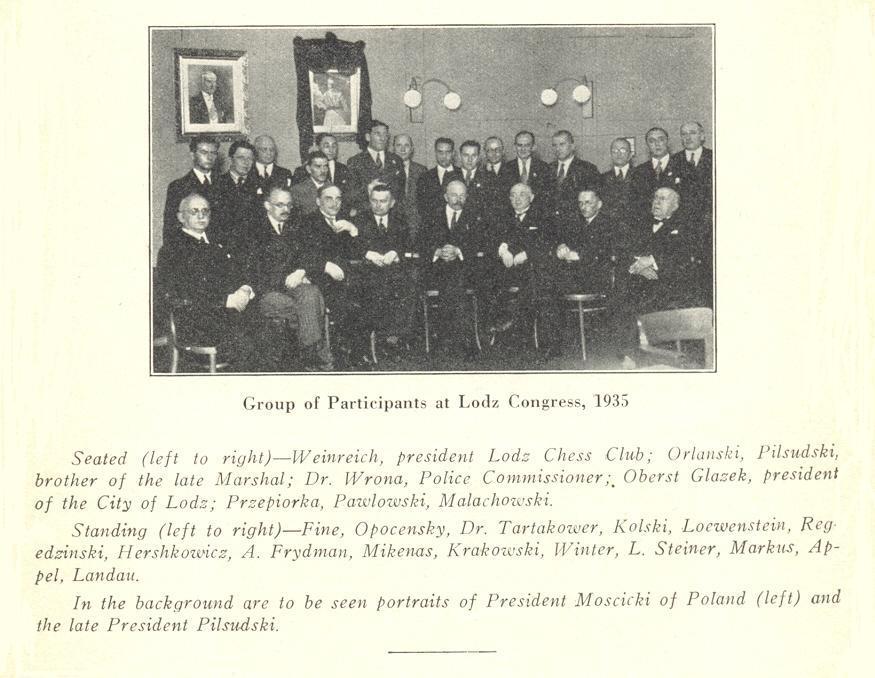

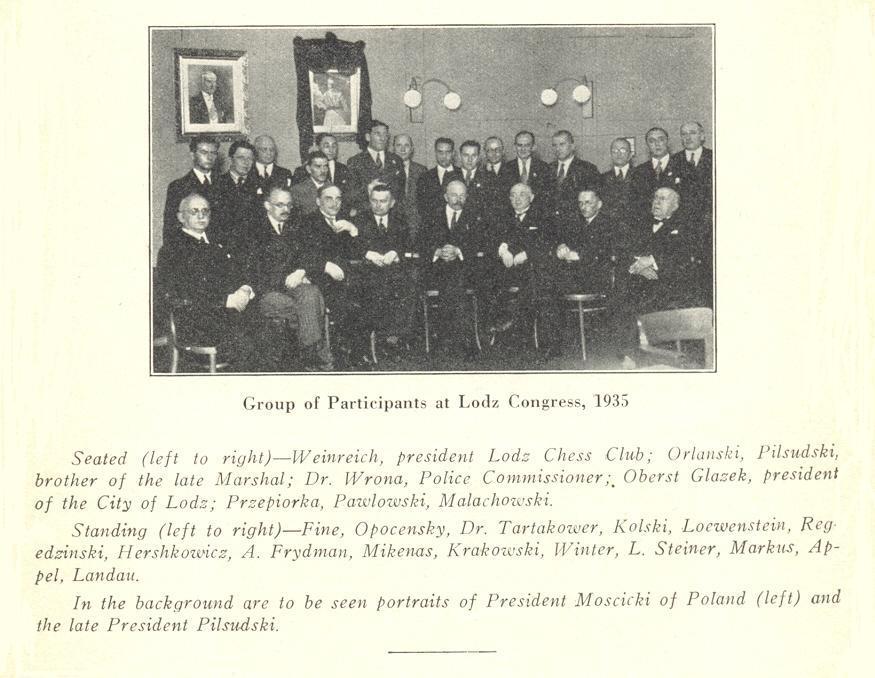

Moreover, the following shot was published on page 130 of the American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1935, the additional figure being Adolf Seitz:

It was taken during a tournament in Łódź, 1935, and William Winter referred to it in his posthumous memoirs (CHESS, 8 March 1963, pages 167-168):

‘Playing conditions were excellent and our accommodation in the Hotel Polonia was luxurious in the extreme. Molly and I had a huge room at the top of the building, one side made up entirely of windows through which nothing was visible save the birds whirling in the heavens. Our fellow guests were an odd company. They included a band of Greco-Roman wrestlers with whose leader, Max Kramer [sic – Krauser], we became very friendly. We went to see him give an exhibition, quite a graceful affair with none of the grunting and heaving which characterizes the all-in version of the sport. A photograph of myself and [Krauser] in the park at Łódź appeared in all the local papers and was reproduced in the magazine CHESS with the caption “Which would you rather be?”’

(3959)

Leonard Barden (London) writes regarding William Winter:

‘I played Willie in the British championship in Buxton in 1950, and my strongest memory is that he showed himself a gentleman. I was in time-pressure with a lost position when he inadvertently allowed a threefold repetition. I claimed, he demurred, and as we waited for the arbiter I was overcome by guilt (I had learnt much from his Chess for Match Players) and confusion, and made a move. Then I realized again that I was right after all. Willie still agreed the draw even though I had invalidated my claim.

I never thought of Willie as “short”. Heights generally were lower then than now, but I guess he was about five feet five or six (1 metre 65-67). The group photograph taken at Nottingham, 1936 shows him looking very unhappy with his legs intertwined, but not appearing specially small.’

William Winter, from page 98 of

his book, co-authored with F.D. Yates, Modern Master-Play

(London, 1929)

We have now found a full-length picture of William Winter, taken during the Nottingham, 1946 tournament and given opposite page 49 in the book on the event published the same year by CHESS, Sutton Coldfield:

Front row, left to right: R.G.

Wade, F. Parr, W. Winter, R.F. Combe, C.H.O’D. Alexander, H.

Golombek, G. Abrahams

Behind: G. Wood, R.J. Broadbent, P.S. Milner-Barry, A.R.B.

Thomas, B.H. Wood

This was taken at the same place as one of the most famous chess group photographs: Nottingham, 1936.

(4059)

A further group photograph including William Winter (at Canterbury, 1930) was published on page 205 of the June 1930 BCM:

Standing (left to right): H.E.

Price, E. Spencer, W. Winter, G. Abrahams, A. Seitz

Seated: F.D. Yates, V. Menchik, Sir George Thomas

(4350)

From page 176 of the June 1939 issue of the Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

The occasion was the match between Holland and England in the Hague, 28-29 May 1939.

(5116)

Below is a photograph taken at Łódź, 1935:

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1935, page 131.

(8734)

Regarding William Winter’s appearance, see too Over and Out.

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) sends us a photograph of William Winter from the collection of Daniël De Mol. It is believed to have been taken in Brussels during the Hampstead Chess Club’s tour in the summer of 1926 (a report on which appeared on pages 407-409 of the September 1926 BCM).

(4356)

A photograph taken at Łódź, 1935:

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1935, page 131.

(4734)

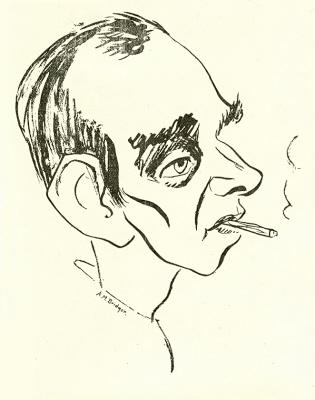

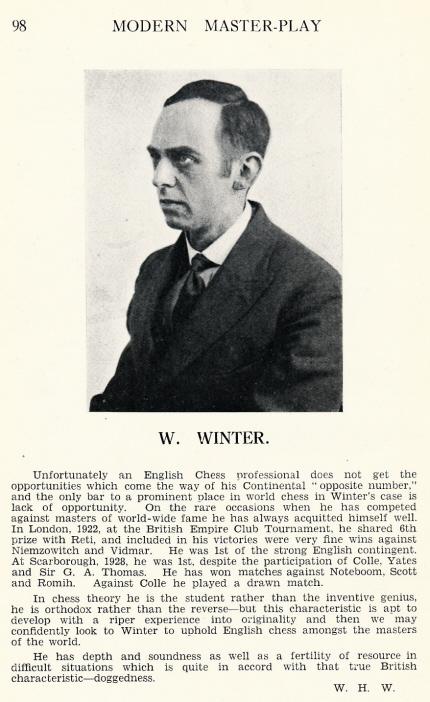

William Winter (frontispiece,

Chess for Match Players, 1936 edition)

The article below by G.H. Diggle, the ‘Badmaster’, comes from page 74 of our publication Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It first appeared in Newsflash, October 1981.

‘William Winter (1898-1955), twice British Champion, a fine chess teacher, and a writer “who could put into one sentence as much as others could into a paragraph”, might have been called in his heyday “The Pride and Horror of British Chess”. Sometimes (notably Yarmouth, 1935 and Scarborough, 1928 where he was accompanied by a lady friend who kept an eye on him like a Probation Officer) he would appear in a college blazer and well-pressed flannels looking like an ascetic curate on holiday – on other occasions he would have been blackballed on sartorial grounds had he attempted to join a village club consisting exclusively of scarecrows. At London, 1945, though reporting only and not competing, he represented the quality press in denims and a tattered old sweater full of holes. It is curious that such a highly educated and cultured man, a courteous and conscientious chess professional in every other respect, never seemed to realize that even chessplayers (the cream of human abnormality) set some limit to hygienic eccentricity. It certainly lost him professional business. The BM was once on the Committee of a local club and the question of whom to invite to give a simul cropped up. The BM, always a “buy British” patriot, suggested Winter and extolled his chess genius, but was routed by a masterful lady member who said “that was all very well, but she refused to be checkmated by the hand of genius if it was garnished with dirty nails”. But strangely enough, Winter himself was physically fastidious in some ways. At Scarborough, as he once remarked afterwards, he actually agreed to a premature draw with the tailender Dr Schubert solely because he could not put up with the Doctor’s chewing gum.

His fairness and sportsmanship over the board were generally agreed to be of the highest order. The BM once heard him relate the following (he was a vigorous and animated raconteur with a staccato voice which tended to rise to a crescendo as he “neared the goal”): “I was playing in a County Match and after a hard struggle was about to play the winning move when some old duffer (he always referred to chess rabbits as Duffers with a great accent on the “D”) – “some old duffer with a whisper like a foghorn hissed out N-B7 and unfortunately it was the right move. As I could find no other way to win, of course the game had to end in a draw.”

Even when at his least presentable, Winter always had a vivid personality. Had he cultivated a presence as well, and had his beard trimmed, he might have ranked with Tarrasch as a great chess pedagogue. But he would have got on better with Labourdonnais, like whom Winter retained his chess faculties to the last. It was even said that he solved a problem on the very day of his death.’

The remark about his writing and annotations (‘he was lucid, putting into a sentence as much as many others put into a paragraph’) appeared in his obituary by ‘J.G.’ (James Gilchrist) on pages 28-29 of the January 1956 BCM.

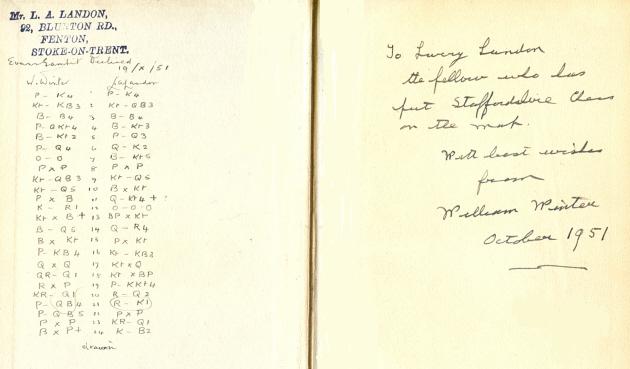

This inscription and game come from one of our copies of William Winter’s Chess for Match Players (London, 1951):

(6121)

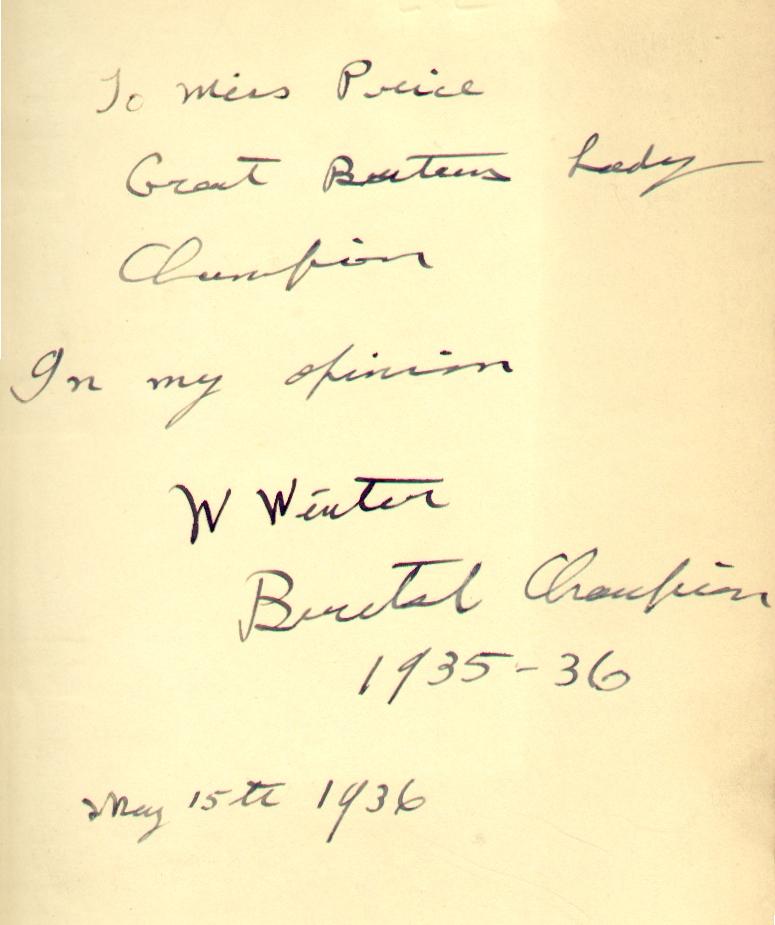

An unabridged, corrected Dover reprint of the 1951 edition was published in 1965. C.N. 162 mentioned a copy of the original (1936) edition in our collection, with a strange dedication to Edith Charlotte Price:

Regarding that original edition of Chess for Match Players, C.N. 2663 noted that Emanuel Lasker praised it highly in a review published in a Russian journal and quoted extensively on pages 194-195 of CHESS, 14 February 1938. To cite just one passage:

‘In the case of the difficult science of the openings on which attention has been focussed for decades, any master, even a world champion, might be proud of such an achievement as this. Neither Euwe nor Alekhine nor Capablanca nor I can boast of such a splendid achievement in this sphere. There is one man in the USSR who would be equal to this task, and that is Botvinnik, but the time has not yet come for him to share his thoughts with the world.’

Can any reader identify the Russian publication?

‘A chessplayer must always have his eyes on the whole board.’

Source: page 200 of the 1951 edition of Chess for Match Players.

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes a Pathé news item on the London, 1946 tournament, featuring Arturo Pomar in play against Ossip Bernstein, as well as footage of some other players, including Savielly Tartakower (briefly) and William Winter. The technical quality is good, with a commentary which is quintessentially English.

(6978)

This caricature of William Winter comes from page 193 of the 14 January 1939 CHESS, which reproduced it in a review of Time and Space, the ‘official organ of the Workers’ Chess League’ and ‘a bright new chess magazine with pronouncedly Left tendencies’. William Winter was named as ‘the editor and author of much of the matter’, although the entry in Betts’ Annotated Bibliography names the editor as E. Klein, also stating that the magazine ran for 23 issues, from August 1938 to June 1940.

Having no copies of Time and Space, we should be grateful to hear of any particularly interesting material it may contain.

(7117)

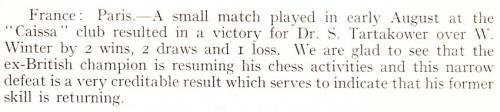

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) asks whether information, including the full game-scores, is available concerning the match between Savielly Tartakower and William Winter in 1938.

This brief report was on page 457 of the October 1938 BCM:

(7630)

A selection of quotes from William Winter’s posthumous memoirs in CHESS was given in C.N. 1197; see too pages 244-245 of Chess Explorations.

In response to C.N. 1197, Kenneth Whyld (Caistor, England) wrote in C.N. 1240:

‘I typed the manuscript for William Winter and tried to interest a publisher in it. After the MS was first typed Winter made many changes, partly to take out the more libellous parts, but also to make factual corrections at my prompting. He did not regard it as appropriate for a master to bother with the “book-keeping” aspects of chess. I found the scores of games for him and I believe that Hooper annotated them.

His wishes were that his memoirs should be published whole, viz., not just the chess part nor just the politics. Also, he did not want them to be serialized in a magazine. As it turned out, none of the main publishers accepted it and I think that B.H. Wood did a fine job, making no cuts.’

The full texts were reproduced by Arthur Hills in William Winter’s Memoirs (Pulborough, 1997).

On 29 May 1989 G.H. Diggle wrote to us:

Concerning William Winter’s criticisms of Edward Tinsley (1869-1937), the relevant pages of CHESS are given below:

(8739)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan:

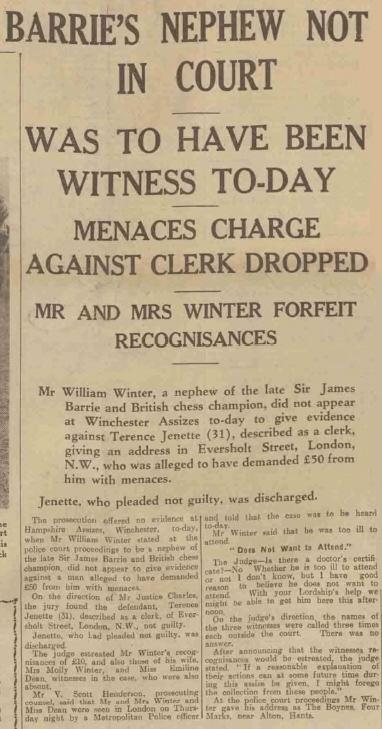

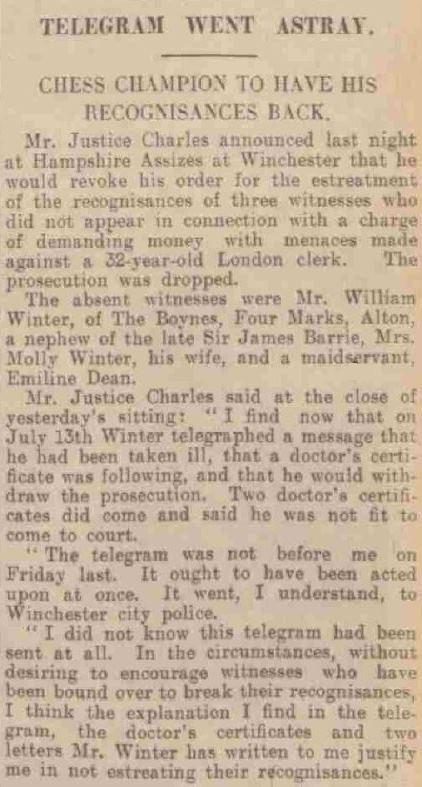

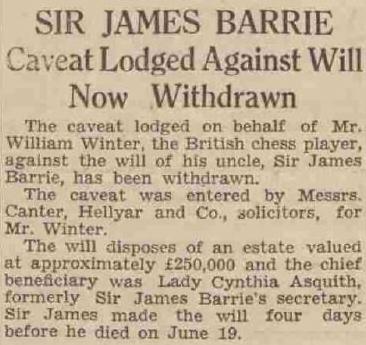

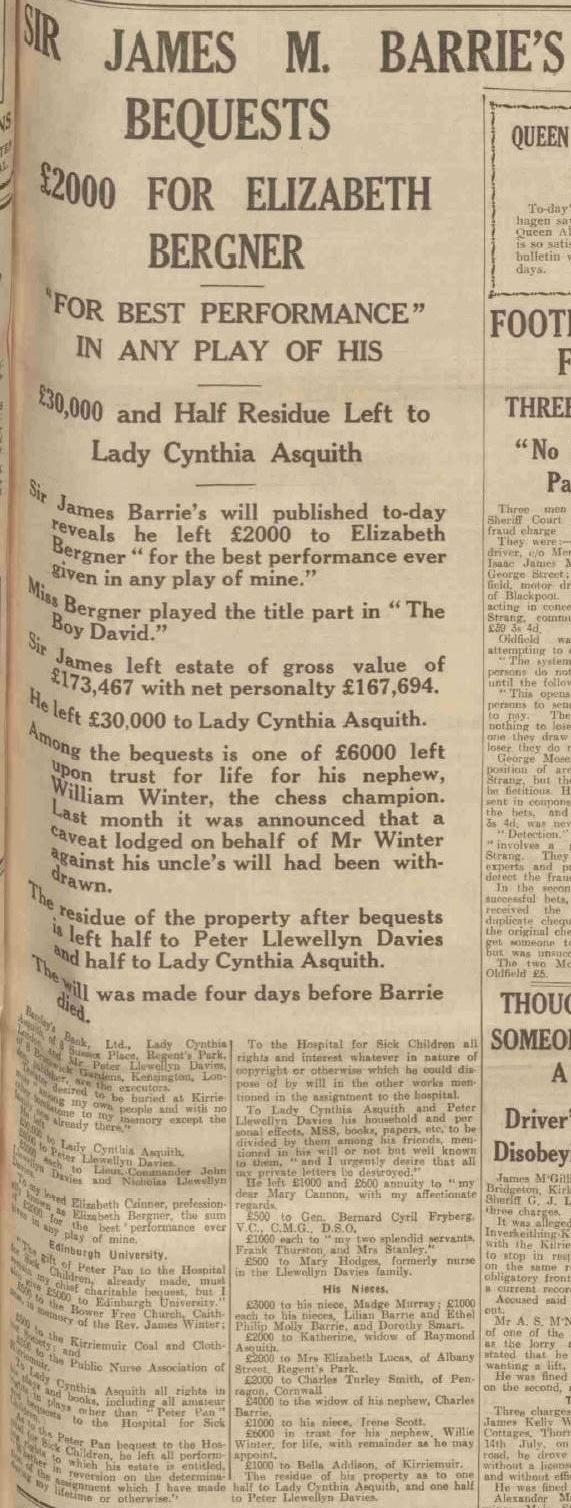

‘In the extract from his memoirs in CHESS which was shown in C.N. 8739, William Winter mentioned his uncle, Sir James Barrie (1860-1937), the Scottish writer who created Peter Pan. In mid-1937 Winter received news coverage, and particularly in the provincial press rather than in national newspapers, for two separate matters concerning family finances.

Firstly, in late June 1937, a few days after Sir James Barrie’s death, Winter accused Terence Jenette of extortion.’

Mr Urcan has provided these cuttings:

Evening Telegraph (Angus, Scotland), 24 June 1937, page 6

Hull Daily Mail, 1 July 1937, page 7

Evening Telegraph (Angus, Scotland), 1 July 1937, page 4

Nottingham Evening Post,

16 July 1937, page 9. (The board position is from Winter v

Thomas, Nottingham, 1936)

Evening Telegraph (Angus, Scotland), 16 July 1937, page 1

Nottingham Evening Post, 21 July 1937, page 3

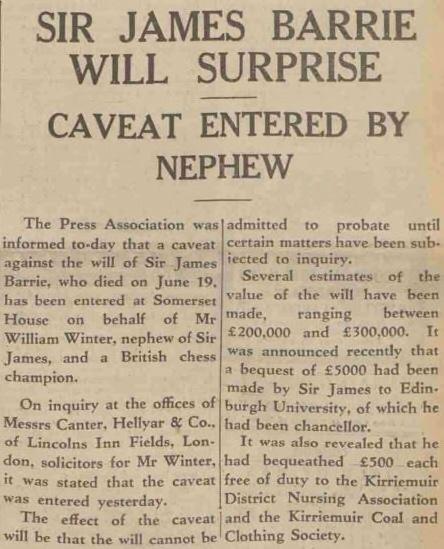

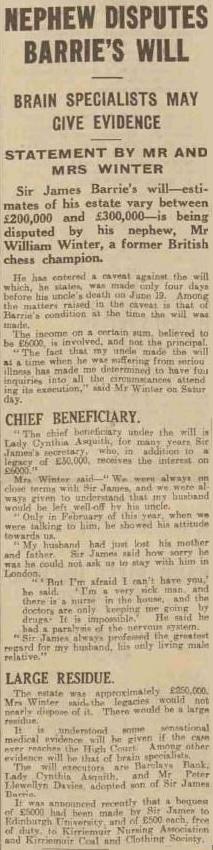

Mr Urcan also supplies newspaper reports concerning William Winter’s unsuccessful attempt to dispute Sir James Barrie’s will by filing a caveat:

Evening Telegraph (Angus, Scotland), 24 July 1937, page 3

Dundee Courier, 26 July 1937, page 8

Gloucestershire Echo, 16 August 1937, page 1

Evening Telegraph (Angus, Scotland), 17 September 1937, page 1.

(8740)

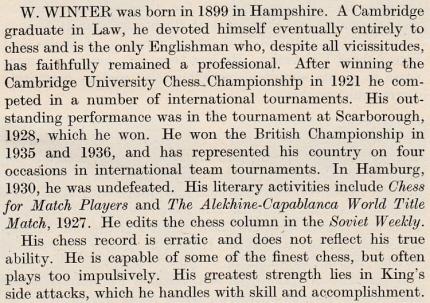

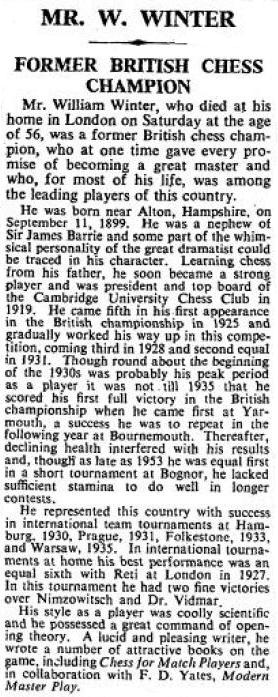

William Winter’s ‘established’ date of birth is 11 September 1898, but a number of old sources gave the year as 1899. These include his obituary on page 11 of The Times, 19 December 1955, which relied heavily on the biographical feature on page 53 of the 1936 edition of Chess Pie.

The year 1899 was also on page 19 of The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match by E. Klein and W. Winter (London, 1947):

A footnote on page 14 mentioned that the chapter in question, ‘Biographies of the Players’, had been written by Klein.

From page 67:

(8743)

The above photograph was also given in C.N. 7787.

William Winter was included in the Scottish team due to play in the 1939 Olympiad, although Scotland eventually decided not to participate. This news item was on page 239 of the April 1939 CHESS:

(8745)

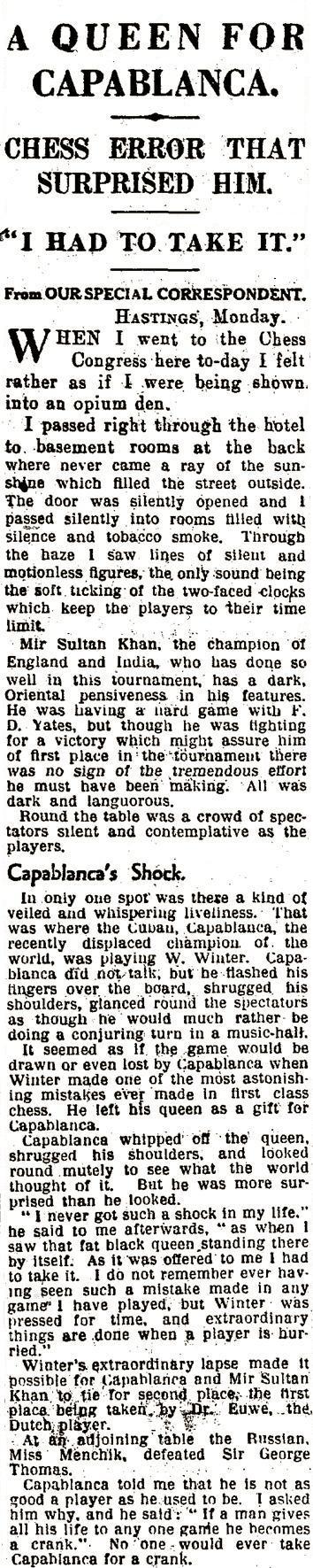

Olimpiu G. Urcan has forwarded the following:

Daily Mail, 6 January 1931, page 7

(8193)

Page 206 of the April 1937 BCM carried an obituary of William Winter’s father, William Henderson Winter:

The previous year (March 1936 issue, page 113), the BCM had reported the death of William Winter’s mother on the night of 10 February 1936. An erroneous obituary of William Henderson Winter had been published on page 331 of the August 1932 BCM and was retracted on page 394 of the September 1932 issue.

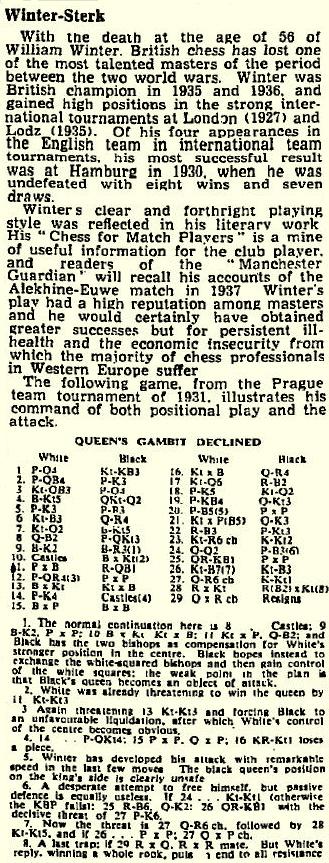

The ‘obituary’ of William Winter on page 3 of the Manchester Guardian, 19 December 1955 was only a few lines long and did not mention his association with the newspaper. A tribute to him appeared in the unsigned chess column on page 8 of the 5 January 1956 edition:

From page 11 of The Times, 19 December 1955:

The obituary may be compared with the biographical text on page 53 of Chess Pie, 1936:

As shown in C.N. 8741, Harry Golombek wrote in his Times column, Review section, 29 September 1973, page 11:

‘... Willie Winter was not available for Stockholm as he had succeeded in twice “losing” his passport and the Foreign Office refused to issue him another.’

From Golombek’s entry on William Winter on page 343 of The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977):

‘He was selected to play at Stockholm in 1937 but, having “lost” his passport three times, he was refused a fresh one by the authorities.’

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) quotes from Golombek’s account on page 48 of The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander (Oxford, 1976), which Golombek co-authored with Bill Hartston:

‘... the BCF team was weakened by the absence of its champion, William Winter. Since he had, somehow or other, contrived to lose his passport for the third time the authorities, claiming a draw by repetition of position, refused to issue him a fresh one.’

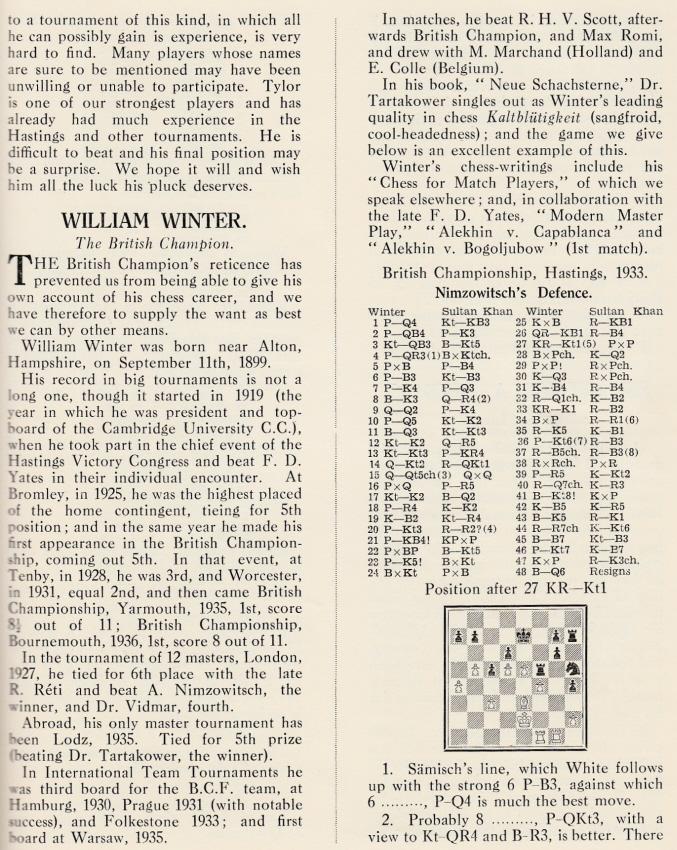

Pages 132-133 of Neue Schachsterne by S. Tartakower (Vienna, 1935):

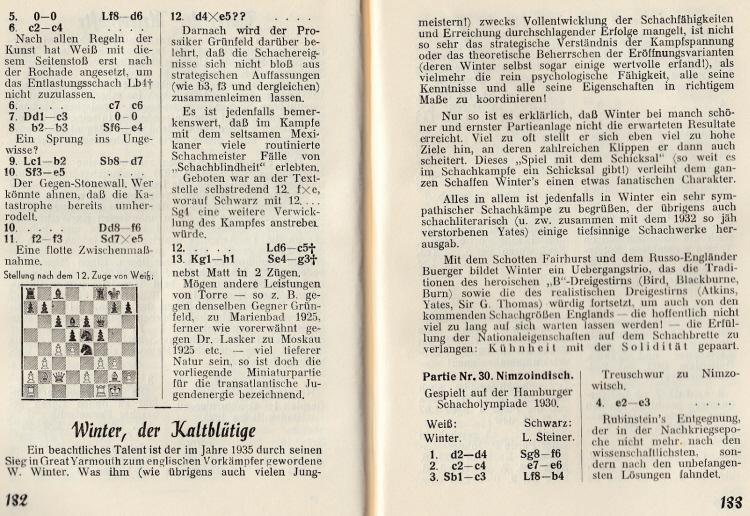

Page 98 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929):

The writer was W.H. Watts. London, 1922 should read London, 1927.

From page 226 of CHESS, July 1946:

The concluding reference to Modern Chess Openings is an error.

Below is a brief extract from the obituary of William Winter on pages 101-102 of CHESS, 24 December 1955:

‘[He] might claim to be considered the most picturesque figure British chess has ever produced. A born Bohemian, as early as his undergraduate days, he evidenced the skill at chess, the eccentricity and the leaning towards Communism which were to mark his whole life. He drew up a blue-print for a red provisional government at Bristol.

... For all his apparent wildness, Winter’s was a gentle, kindly personality capable of deep friendships and loyalties.’

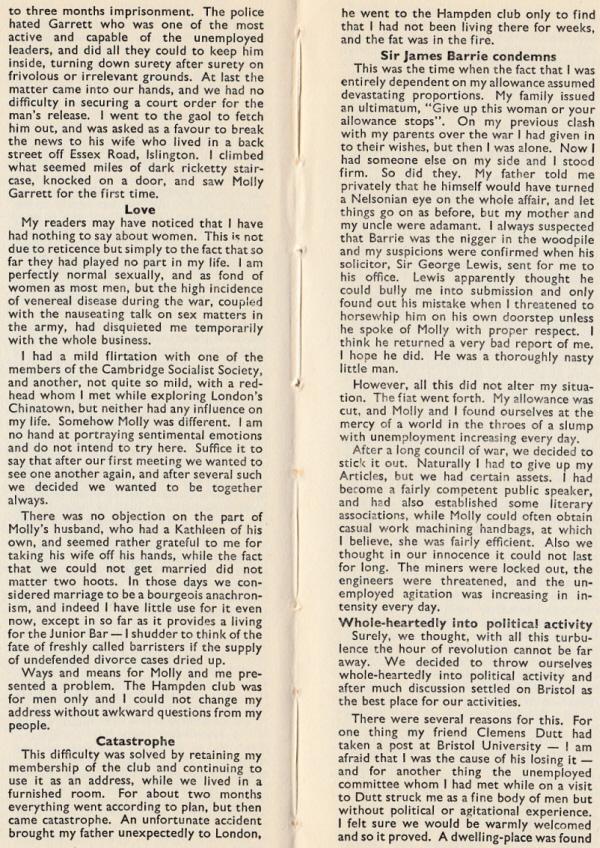

Another extract from William Winter’s memoirs in CHESS (1 January 1963, pages 78-79):

A passage regarding F.J. Marshall on page 17 of Kings of Chess:

‘Later I was with him at the International Team Tournaments in Prague and Warsaw, where he led the American team to success. Into these national battles he threw himself with a fervour quite foreign to the phlegmatic temperament which he displayed in his own individual tournaments, and, on the first occasion, when he was asked to make a speech at the concluding banquet, he was so overcome by emotion that he could only wave the Stars and Stripes and shout “Hip-Hip-Hurrah”.’

In his memoirs on pages 165-166 of CHESS, 9 March 1963 W. Winter wrote:

‘Proceedings concluded with a magnificent banquet attended by several members of the Czech Government, which lasted until the small hours of the morning. I am afraid I have no very clear recollections of this. The last thing I remember was Marshall replying to the toast of the victorious American team, rising unsteadily to his feet, waving the Stars and Stripes and shouting “Hip-Hip-Hurrah” and then collapsing in his chair. When describing this incident I have usually said that he was overcome by emotion but, in these candid memoirs, I must admit there were other causes.’

As shown in our feature article, there have been contradictory claims as to whether William Winter was born in 1898 or 1899. Now, however, John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In the recently available index of births on the website of the General Register Office, the only birth of any William Winter between 1897 and 1902 for whom the mother’s maiden surname was Barrie was registered in the last quarter of 1897 in the district of Alton (volume 2c, page 177). This means that the correct year of birth of the former British champion is 1897.

The entry is consistent with the age of three which was given for William Winter in the 1901 census, when he was living with his Scottish-born parents, William Henderson Winter and Margaret Winter at “The Boynes”, Medstead, near Alton (source: National Archives, RG 13/1099, f. 72). Similarly, in the 1911 census he was aged 13, described as a student, still with his parents at “The Boynes” (National Archives, RG 14/6216/196).

He can be identified in the “National Registration: 1939 Register” as the William Winter, “author and journalist”, who was living at 27 Guilford Street, Holborn (National Archives, RG 101/250A). His date of birth in that document is given as 11 September 1897, which is exactly a year earlier than the date of birth mentioned in C.N. 8743. (The description of “author and journalist” is the same as was used for William Winter in the National Probate Calendar entry for his father, William Henderson Winter, whose will was proved on 2 April 1937.)’

(10213)

In the light of Mr Townsend’s research, we have amended the title of the present article from ‘William Winter (1898-1955)’ to ‘William Winter’.

From Over and Out:

Purely by way of example, we examine here one particular untruth by K. Whyld in his review of Kings, Commoners and Knaves in the May 1999 BCM, a piece which was accompanied (on page 271) by a photograph with this caption:

‘William Winter – did Edward Winter perhaps confuse his namesake with Yates?’

The photograph was there to illustrate, and reinforce, the following attack by K. Whyld on a KCK item:

‘On page 181 he [E.W.] notes that B.H. Wood wrote “Yates died a sloven, a drunkard, in pathetic circumstances” and Winter adds “A mix-up with William Winter?” Tremendous. Two slurs for the price of one, and a bloody nose for Wood, who at least knew what he was talking about.’

Whyld then added with a further sneer: ‘They’re all dead anyway, so let’s publish.’

Let us return to the facts. On page 59 of J. Giżycki’s A History of Chess B.H. Wood wrote, ‘Yates died a sloven, a drunkard, in pathetic circumstances’. A C.N. item from 1987 which was reproduced on page 181 of KCK quoted those words of Wood’s, and we added a five-word comment of our own: ‘A mix-up with William Winter?’ The reason for this query is self-evident: the lack of such claims about Yates, coupled with the abundance of them (strongly and openly expressed) concerning William Winter. For example, the obituary in CHESS, Wood’s own magazine (24 December 1955 issue, page 101), stated that although W.W. was occasionally well-groomed he ‘might turn up at a chess match or a meeting in a state of almost indescribable filth – clothing and person alike’. Another figure well acquainted with W.W. was Harry Golombek, who wrote on page 343 of his 1977 Encyclopedia that away from the board W.W. was ‘more often than not, drunk’.

Moreover, a reader of CHESS, J.Y. Bell, discussed both F.D. Yates and W. Winter on page 212 of the 20 April 1963 issue:

‘Yates, who seems to me to have been at least as hard up as Winter, managed to present a decent appearance in public.’

To this, the Editor (i.e. B.H. Wood, the man ‘who at least knew what he was talking about’) added immediately afterwards:

‘Yes, Winter often presented a most filthy and disreputable appearance.’

That is the public record. We have not originated a single slur, let alone two. We have not given B.H. Wood ‘a bloody nose’. We merely asked a legitimate five-word question about the possibility of a mix-up over W. Winter and F.D. Yates. Remarkably, though characteristically, Whyld twisted that question into a ‘claim that Wood was wrong’.

We add the following exchanges in C.N. 1438 (after our five-word comment in C.N. 1422, ‘A mix-up with William Winter?’):

From K. Whyld:

‘I believe you are wrong in thinking there has been a mix-up. Winter died of tuberculosis in London University Hospital. Yates died from a gas leak. Both were drinkers, and both casual, at least, in their appearance. I should make it clear that I never met Yates, and speak of him by hearsay only.’

Apart from B.H. Wood’s quoted paragraph, we have never see any suggestion in print that Yates was ‘a sloven, a drunkard’, whereas these epithets have frequently been applied to William Winter.

There the matter stood until, some 11 years later, Kenneth Whyld attacked us in the BCM, as quoted above.

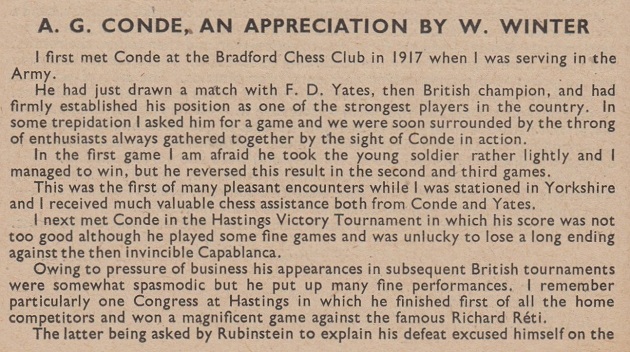

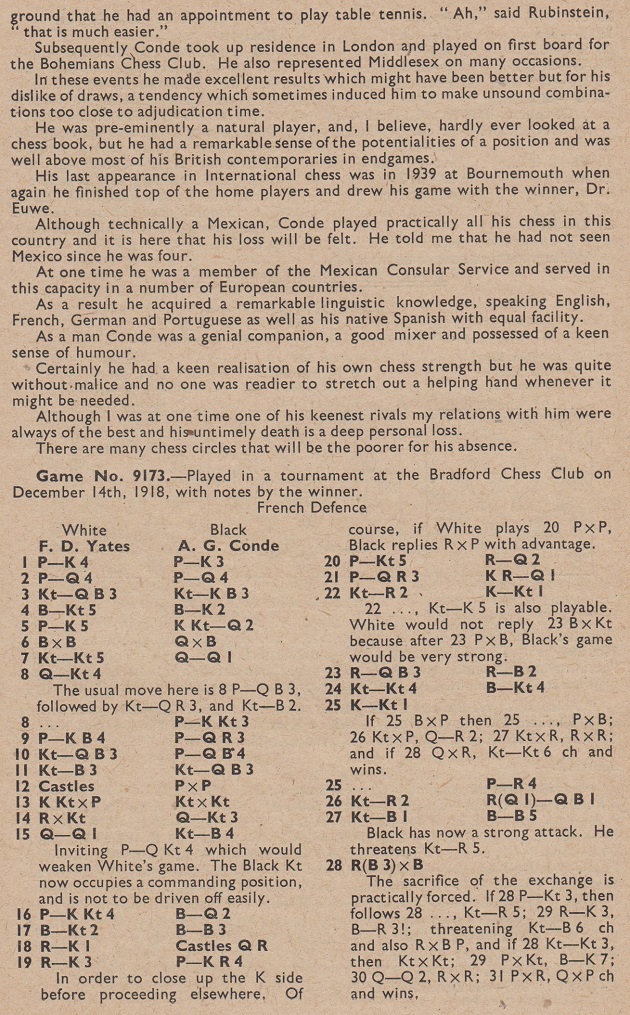

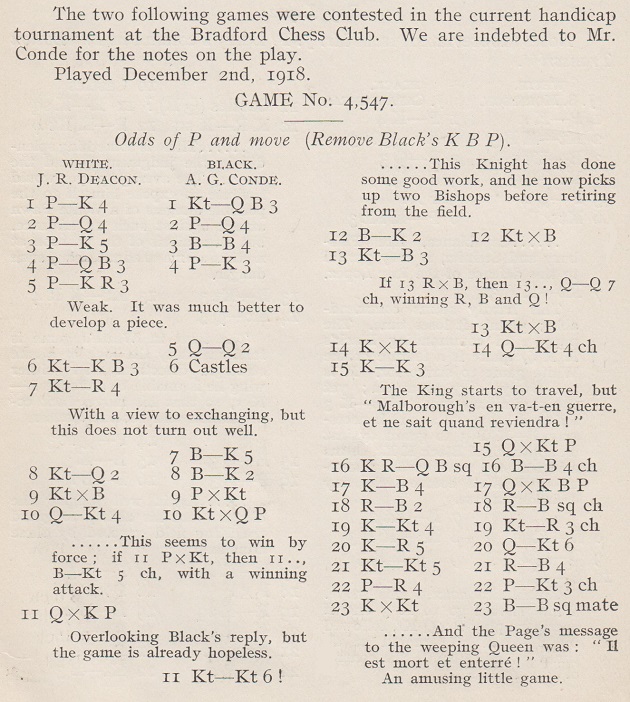

A tribute to Adrián García Condé (1886-1943) by William Winter was published on pages 202-204 of the September 1943 BCM:

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 Bxe7 Qxe7 7 Nb5 Qd8 8 Qg4 g6 9 f4 a6 10 Nc3 c5 11 Nf3 Nc6 12 O-O-O cxd4 13 Nxd4 Nxd4 14 Rxd4 Qb6 15 Qd1 Nc5 16 g4 Bd7 17 Bg2 Bc6 18 Re1 O-O-O 19 Re3 h5 20 g5 Rd7 21 a3 Rhd8 22 Na2 Kb8 23 Rc3 Rc7 24 Nb4 Bb5 25 Kb1 a5 26 Na2 Rdc8 27 Nc1 Bc4

28 Rcxc4 dxc4 29 Rd6 Qb5 30 Ne2 Na4 31 Qc1 c3 32 Nd4 cxb2 33 Qd2 Qc4 34 Qe1 Nc3+ 35 Kxb2 Qa2+ 36 Kc1 Qxa3+ 37 Kd2 Nb5 38 Qg3 Qb4+ 39 White resigns.

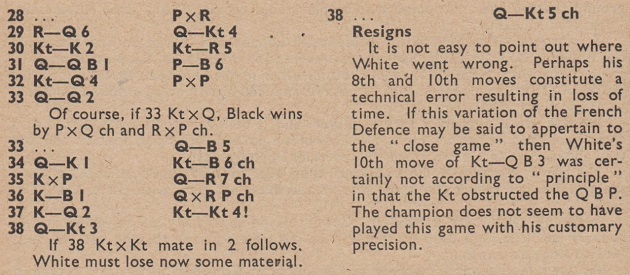

Those notes by Condé to his victory over Yates were reproduced from pages 57-58 of the February 1919 BCM, whose previous page had this miniature against J.R. Deacon (given on pages 121-122 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and in Royal Walkabouts):

1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 c3 e6 5 h3 Qd7 6 Nf3 O-O-O 7 Nh4 Be4 8 Nd2 Be7 9 Nxe4 dxe4 10 Qg4 Nxd4 11 Qxe4

11...Nb3 12 Be2 Nxc1 13 Nf3 Nxe2 14 Kxe2 Qb5+ 15 Ke3 Qxb2 16 Rhc1 Bc5+ 17 Kf4 Qxf2 18 Rc2 Rf8+ 19 Kg4 Nh6+ 20 Kh5 Qg3 21 Ng5 Rf5 22 h4

22...g6+ 23 Kxh6 Bf8 mate.

Regarding William Winter’s suggestion that Condé ‘hardly ever looked at a chess book’, the following ‘is said to have’ remark appeared on page 11 of the Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 6 July 1929 and, without any mention of that newspaper, on page 243 of the Chess Amateur, August 1929:

‘Mr A.G. Condé, the Mexican chessplayer, who took part in the recent little tourney at the Gambit Café, London, is said to have learnt chess when 14 years of age by studying the Hastings Chess Tournament Book of 1895. This was the first book he studied from, and in a few months [he] played over every game in the volume, carefully following the notes. In due time he became a first-class player.’

(10903)

Eric Fisher (Hull, England) reports that he has three articles by William Winter in Lilliput (November 1949, June 1950 and November 1950) and asks whether there are any others. He has provided pages from the June 1950 and November 1950 issues.

(11087)

Terry Hart (Cambridge, England) asks what became of the papers of William Winter, including the manuscript of his memoirs (see C.N.s 1197 and 1240 above).

The above photograph of William Winter is shown courtesy of the Universal History Archive/Universal History Group. C.N. 6121 had a less good version, the frontispiece to the 1936 edition of his book Chess for Match Players.

(11879)

John Townsend writes:

‘I have obtained a copy of William Winter’s will, dated 11 June 1954. The main legatee was Evelyn Ethel Olorenshaw, but Clause 3 stated that he bequeathed to David V. Hooper (94 High Street, Reigate) “all my chess manuscripts and publications and any royalties accrued or to accrue due in respect thereof in the confident knowledge that he will do everything necessary or proper to perpetuate my name”.

The National Probate Calendar states that Winter died on 17 December 1955. His address was given as 145 King Henry’s Road, Hampstead, London. The will was proved in London on 5 March 1956, the effects amounting to £4,819 6s. 8d.

David Hooper’s will, made on 19 April 1986 and proved on 24 June 1998, stated that he bequeathed all his chess-related material and rights to Kenneth Whyld. The latter left his chess collection to the Musée suisse du jeu, La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland.’

(11889)

William Winter’s views on Joseph Walter Russell (1849-1931) are given in C.N. 4037.

See too G.H. Diggle, the Chess Badmaster.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.