Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [81] | next >> | Current column |

7022. Leningrad v Moscow match, 1937

Some well-known figures are in this photograph taken during the Leningrad v Moscow team match (30 June and 1 July 1937):

Source: Chess Review, September 1937, page 210.

7023. Otho Ernst

Michaelis (C.N. 6766)

From John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

‘My work on a game collection and biography of Major Otho E. Michaelis of the United States Army, Ordnance Corps, has intrigued me for several years now, and not least because Michaelis appears in so many geographically varied chess contexts: in New York City, 1860, winning a rook-odds game against Paul Morphy; in Detroit, 1869, winning the Michigan State Chess Association title; in Philadelphia, in 1882 and 1884, winning the Philadelphia Chess Club’s championship, as well as off-hand games with Steinitz; and at various times in St Paul, Minnesota, in Troy, New York, in Boston and, finally, in Augusta, Maine. His chess followed his military career. From a variety of sources over 130 games and game fragments have been collected for the book. Steinitz acknowledged Michaelis as among the most prominent amateur chessplayers in the country, and regretted his passing. So did many others, both in and out of chess.

Of at least equal interest is Michaelis’ career in the military, which took him as a teenager on the Gettysburg campaign in July 1863; to Nashville for Hood’s disastrous attack on General George H. Thomas’s forces, where he served as Thomas’s chief of ordnance (Michaelis was the first non-West Point graduate to qualify to enter the ordnance corps); to the Little Big Horn to identify bodies two days after Custer’s defeat; to the top of Mount Whitney in California; to the lecture hall of the prestigious Franklin Institute in Philadelphia; and his work in a variety of federal arsenals conducting experiments for the ordnance corps. An expert in chess, whist, ordnance, metallurgy, electricity, meteorology, translation and perhaps other fields too, Michaelis, the 1862 valedictorian of the Free Academy of New York (four years later renamed the City College of New York), was something of a Renaissance man, in the term’s best sense.

Until recently, however, his family has in some ways proved more elusive than his chess or military careers. Having obtained his pension records from the time when his widow applied for an increase in funds, I can now share further information. As is known, Michaelis was born in Germany on 3 August 1843 and died in Augusta, Maine on 1 May 1890. He died of a spinal infection at the relatively young age of 46. His wife, Kate Kercheval Woodbridge Michaelis, was born on 2 February 1846, in Detroit, Michigan.

Otho and Kate Michaelis were married in Detroit on 29 December 1868. They had nine children over a period of 20 years, only six of whom outlived their father. All but two were born at various army arsenals across the country. The following list of their children is taken from Kate Michaelis’s sworn affidavit found among the pension records:

1. Guy Michaelis, born on 14 September 1869, at Detroit Arsenal, Dearbornville, Michigan;

2. Marion Field Michaelis, born on 1 September 1871, at Watertown Arsenal, Boston, Massachusetts;

3. George Veil Shepard Michaelis, born on 21 June 1873, at Watertown Arsenal, Boston, Massachusetts;

4. Francis Woodbridge Michaelis, born on 22 April 1875, at Allegheny Arsenal, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania;

5. Margaret Lawrence Michaelis, born on 27 May 1877, at St Paul, Minnesota;

6. Otho E. Michaelis, Jr., born on 1 March 1879, at St Paul, Minnesota;

7. Kathleen Alfred Michaelis, born on 22 March 1882, at Frankford Arsenal, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;

8. Sidney Clare Morgan Michaelis, born on 22 October 1885, at Watervliet Arsenal, West Troy, New York;

9. Helen Michaelis, born on 6 October 1889, at Kennebec Arsenal, Augusta, Maine.

The couple’s time at Kennebec Arsenal proved deadly for the family. Guy, their eldest son, died there of consumption, aged 18, on 11 October 1887. Helen, their youngest child, died the day she was born, 6 October 1889. Margaret, aged 12, died less than two months after her youngest sister, on 1 December 1889, when she fell through the ice on the pond behind their home. Michaelis attempted to rescue her, but had to be rescued in turn, unconscious, and he spent over two weeks in hospital. The following year, Michaelis himself died.

Questions regarding the Michaelis family still remain, and I should be grateful to any readers who can provide information or leads on such matters as the following:

1. What was Michaelis’ actual place of birth in Germany and who were his parents?

2. What is the date of death and place of burial of his wife, Kate Kercheval Michaelis? (Pension records indicate that she was still living in the early to mid-1920s, in Brookline, Massachusetts. She apparently never remarried.)

3. A descendant of Otho E. Michaelis may still be alive. Otho E. Michaelis, Jr. died in a car accident in Georgia on 31 March 1919, having turned 40 at the beginning of that month. However, it appears that there was an Otho E. Michaelis III, as well as an Otho E. Michaelis IV. The name is sufficiently rare for it to seem highly unlikely that an Otho E. Michaelis IV was unrelated to the nineteenth-century chessplayer. During the 1990s, and earlier, a Dr Otho E. Michaelis IV, a research biologist with the Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Services, US Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD, published numerous scientific articles. He was also an adjunct associate professor, Division of Renal Diseases, Department of Medicine, George Washington University, Washington, DC. Any information provided by readers which leads to contact with him or with any descendant of the chessplaying Otho E. Michaelis will be much appreciated.

4. A photograph or engraving of Michaelis, or of any of his family members, is also highly desired.’

7024. Chess prodigies (C.N. 6148)

We note a further book on the subject of chess prodigies: Шахматные вундеркинды (Shakhmatnye vunderkindy) by E. Gik (Moscow, 2006). Its main focus is on relatively recent players.

7025. The Termination

Some chess chroniclers are obliged to attempt, nolens volens, to sum up in a paragraph or two the complexities and uncertainties of the Termination of the first Karpov v Kasparov match (1984-85). We wonder whether readers can quote a better summary than the one on page 84 of the revised edition of Leonard Barden’s book Play Better Chess (London, 1987):

‘... Karpov began to sit on his lead, just waiting for Kasparov to make a fatal slip. But the match was now into its fourth and fifth month, and Karpov’s strength was ebbing. Kasparov got back to 5-1, then Karpov suddenly lost two games in a row for 5-3 after 48 games. The match was becoming an embarrassment to the Soviet authorities, and play was transferred from the grand Hall of Columns to the Hotel Sport in the suburbs.

After 48 games Florencio Campomanes, President of the International Chess Federation (FIDE), took his controversial and unprecedented decision to annul the match. He made his announcement at a chaotic Moscow press conference where both Karpov and Kasparov declared they wanted to continue to play. Campomanes then led the grandmasters backstage for private discussions after which he confirmed his decision. K and K blamed each other, the chess world was aghast at what was seen as an arbitrary and false conclusion which many thought was made to rescue a tottering Karpov. Objectively, however, it was still much more likely that Karpov would win one game before Kasparov won three, and the defending champion played under a psychological burden in the next K v K series in 1985.’

7026. Labatt v Marshall

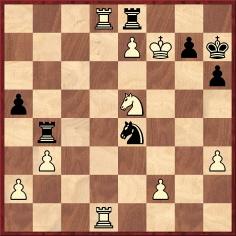

Leon L. Labatt – Frank James MarshallNew Orleans, 13 March 1913

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 c4 d5 6 Nc3 Nxc3 7 dxc3 Be6 8 Qb3 Nc6 (‘After the game was over, Marshall remarked that perhaps 8...dxc4 was stronger at this point than the text move; but he had been willing to give up the pawn for the development of his pieces.’) 9 Qxb7 Na5 10 Qa6 c6 11 cxd5 Qxd5 12 Be3 Be7 13 Be2 O-O 14 Qd3 Rab8 15 b3 Ba3 16 Rd1 Qxd3 17 Bxd3 Bb2 18 c4 Bc3+ 19 Ke2 Rfe8 20 h3 Rbd8 21 g4 c5 22 Kf1 f5 23 Bxc5

23...Nxc4 (‘One of Marshall’s surprises (called by the masters “Marshall’s swindles”). The knight cannot be captured with advantage.’) 24 gxf5 Nb2 25 fxe6 Nxd3 26 e7 Rd7 27 Ba3 a5

28 Ke2 (‘This is the psychological moment for the king to come into the game, and Judge Labatt showed excellent judgment and daring in bringing his majesty unattended into the enemy’s country. However, the maneuver ending with the play of 37 Kf7 wins the game for White.’) 28...Nf4+ 29 Ke3 Nd5+ 30 Ke4 Nf6+ 31 Kf5 Rd5+ 32 Ke6 Rb5 33 Rd8 Bb4 34 Bxb4 Rxb4 35 Rhd1 h6 36 Ne5 Kh7 37 Kf7 Ne4

(‘Marshall now sets a neat little trap for White; if here 38 Rxe8 Ng5+ 39 Kf8 Rf4+ 40 Nf7 Rxf7 mate.’) 38 Kxe8 Rb7 39 Kf8 Ng5 40 e8(Q)

40...Kh8 (Threatening 41...Nh7 mate.) 41 R1d7 Resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, June 1913,

pages 138-139, with a correction on page 151 of the July

1913 issue. The notes cited came from the New

Orleans Times-Democrat.

The conclusion of this (individual) game was given in C.N. 1291. See pages 14-15 of Chess Explorations.

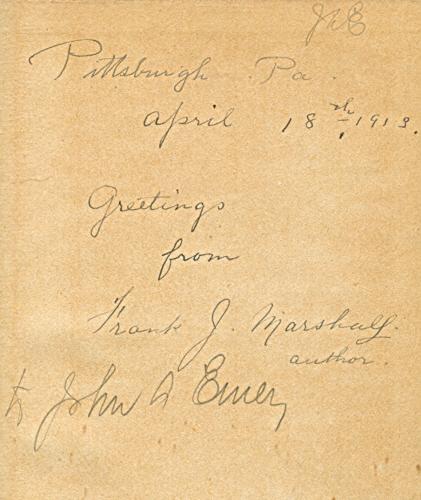

7027. Marshall inscription

Our collection includes a copy of Marshall’s book Modern Analysis of the Chess Openings (Amsterdam, 1912 or 1913), inscribed by him in Pittsburgh on 18 April 1913:

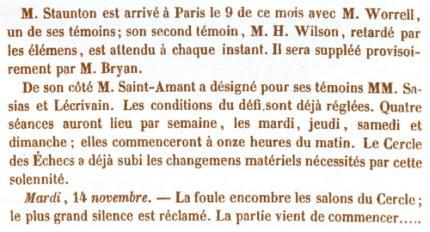

7028. John Worrell

Lynne Leonhardt (Claremont, WA, Australia) is seeking information about her great-great-great-grandfather, John Worrell, who was a second to Staunton in the 1843 match against Saint-Amant in Paris.

We have noted fewer particulars in the Chess Player’s Chronicle than in Le Palamède. From page 481 of the 15 November 1843 issue of the latter:

The agreement between Staunton and Saint-Amant, signed on 13 November 1843, was given on page 563 of the French magazine, 15 December 1843, and the following was published on page 31 of the 15 January 1844 issue:

‘M. Staunton s’est trouvé placé dans des conditions bien défavorables en venant lutter sur une terre étrangère, et se trouvant ensuite abandonné par ses témoins, MM. Worrell et Wilson, qu’une grave et subite maladie a forcés de retourner en Angleterre. Nous devons dire cependant, qu’ayant été dignement remplacés par MM. Bryan et Dizi, leur absence à peine s’est fait sentir.’

7029. Josef Hašek

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks whether firm information is available about the death-date of Josef Hašek. Whereas ‘1976’ is given on page 123 of Malá encyklopedie šachu by J. Veselý, J. Kalendovský and Bedrich Formánek (Prague, 1989), our correspondent points out that the listing Almanach českých problémistů by Z. Libiš has ‘1981’. In neither case is a precise date offered.

7030. Americans and chess

‘Chess will never become a popular game with Americans ...’

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) sends this cutting from page 2 of the Brooklyn Eagle, 24 May 1858:

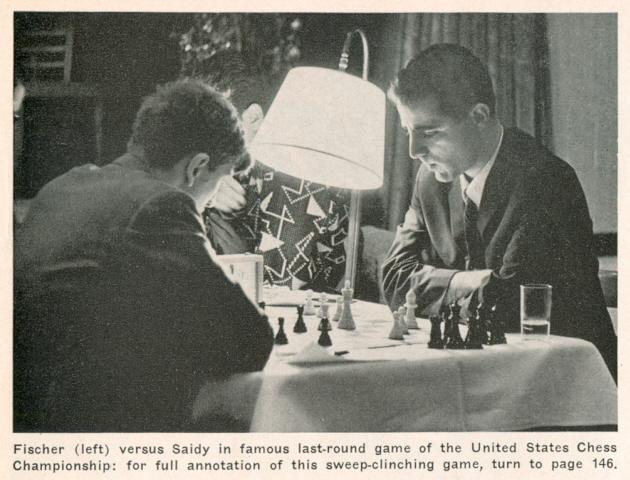

7031. Saidy v Fischer

From Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA):

‘While recently reading the fine book Endgame Strategy by Mikhail Shereshevsky (Oxford, 1985) and comparing its analysis (on pages 176-177) of Saidy v Fischer, US Championship, 1963-64 with what appears on pages 312-314 of volume four of Garry Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors, I noticed a discrepancy regarding Black’s 47th move. Kasparov’s book indicates that Fischer played the decentralizing move 47...Nh5, while Shereshevsky has 47...Ne4. The latter move is corroborated by Anthony Saidy in a letter published in Larry Evans’ column in the November 1986 Chess Life (page 47).

Position after 47 Bh4

Which move was played, ...Ne4 or ...Nh5? Kasparov’s analysis at move 48 to save White, which includes the move 49 Bf2, does not work with the black knight on e4.’

The score was published on page 35 of the February 1964 Chess Life and on page 146 of the May 1964 Chess Review. In each case the move given was 47...Ne4.

On the other hand, Saidy contributed an introduction to the game in Bobby Fischer by Karsten Müller (Milford, 2009) – see pages 248-249 – and in that book the game-score had 47...Nh5, with a question mark and the comment ‘too slow’.

A photograph from earlier in the game appeared on page

132 of the May 1964 Chess Review:

7032. Otho Ernst Michaelis (C.N.s 6766 & 7023)

We are grateful to Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) for documentary data regarding Otho E. Michaelis. It has been forwarded to John Hilbert.

7033. Dispute

Tartakower wrote as follows in CHESS, May 1940, pages 188-189:

‘The conclusion of the tournament at Budapest in 1928, the one called the “Siesta” tournament, was marked by a dispute. When the last round started, Capablanca led, a point in front of Marshall. It became common knowledge that his game with Vajda had been agreed a draw before a move had been made, with the official consent of the tournament committee. Marshall protested violently, on the grounds that this arrangement deprived him of all chance of sharing in the second prize. The “chance” proved purely theoretical (when he lost to L. Steiner so could not have caught up with Capablanca in any case). Capablanca, moreover, had little reason to fear a defeat at Dr Vajda’s hands. Marshall, however, was badly put out by this incident and took particular pains to inflict on Dr Vajda, the next time he came up against him, a resounding defeat.’

Brief comments: a) Marshall won second prize; clearly, it was the first prize he was eager to share. b) L. Steiner did not play at Budapest, 1928, though ‘E.’ and ‘H.’ did. c) Marshall’s resounding defeat of Vajda was in fact a 35-move draw at the 1930 Hamburg Olympiad.

The above item (C.N. 987) appeared over 25 years ago, but we have yet to obtain clarification of Tartakower’s claims.

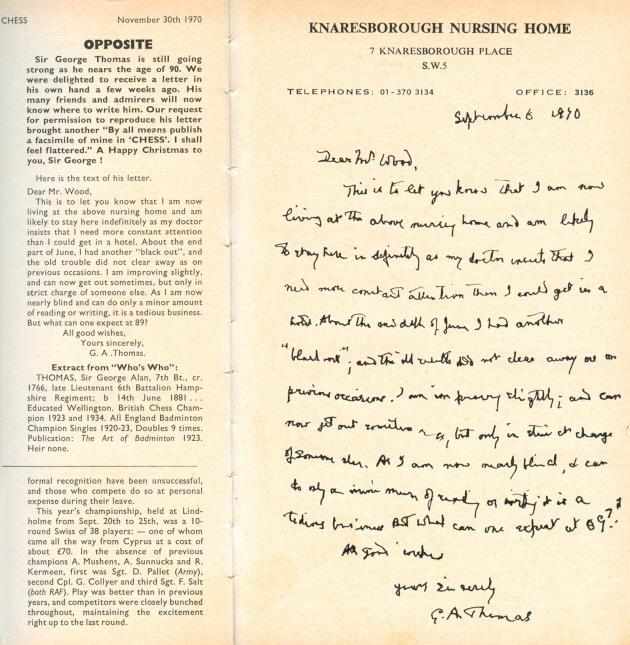

7034. Sir George Thomas

From pages 116-117 of CHESS, 30 November 1970:

7035. Berlin, 1920

A quote from page 235 of Chess Review, October 1937:

‘The Berlin tournament of 1920, played during the post-War turmoil and financed very generously by Bernhard Kagan, probably has a higher percentage of good games than any other tournament ever played.’

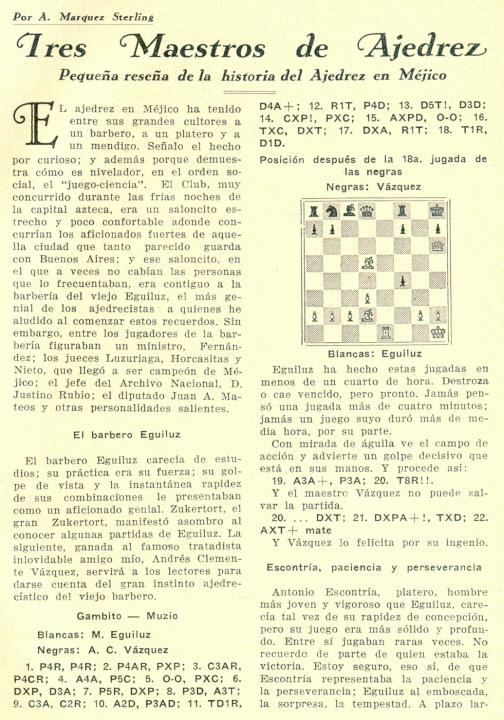

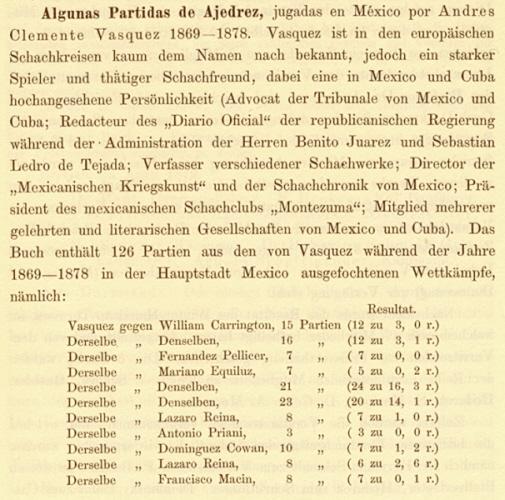

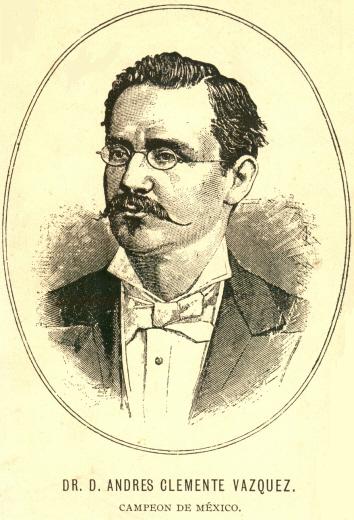

7036. Eguiluz and Vázquez

White to move. What did he play? Answer

We shall return to this question towards the end of the present item, but first a game given in C.N. 1662 (see page 76 of Chess Explorations):

Mariano Eguiluz – Andrés Clemente VázquezOccasion?

Muzio Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 O-O gxf3 6 Qxf3 Qf6 7 e5 Qxe5 8 d3 Bh6 9 Nc3 Ne7 10 Bd2 c6 11 Rae1 Qc5+ 12 Kh1 d5 13 Qh5 Qd6 14 Nxd5 cxd5 15 Bxd5 O-O 16 Rxe7 Qxe7 17 Qxh6 Kh8 18 Re1 Qd8 19 Bc3+ f6

20 Re8 Qxe8 21 Qxf6+ Resigns.

Source: pages 45-46 of Un poco de ajedrez by Manuel Márquez Sterling (Mexico City, 1893). C.N. 1662 quoted the author’s comment ‘This game places Señor Eguiluz on the same level as the Morphys and Anderssens’. We mentioned too the similarity with the finish to Morphy’s blindfold win against P.E. Bonford in New Orleans, 24 March 1858.

Eguiluz’s victory was also given on page 299 of the November 1933 issue of the Argentinian magazine El Ajedrez Americano:

The following appeared on page 173 of the June 1879 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

Since Vázquez’s book Algunas partidas de ajedrez is not in our collection we shall be grateful to know what information it provides on his encounters with Eguiluz. In the meantime, below are three further games between the two players:

Mariano Eguiluz – Andrés Clemente Vázquez‘Played some years ago’, Mexico City

Bird’s Opening

1 f4 d5 2 d4 c5 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 e3 c4 5 c3 Bf5 6 Be2 Rc8 7 Nbd2 e6 8 O-O Nf6 9 b3 b5 10 b4 Bd6 11 a4 a6 12 axb5 axb5 13 Ne5 Bxe5 14 fxe5 Ne4 15 Nxe4 Bxe4 16 Ra6 O-O 17 Bf3 Bd3 18 Rf2 Qc7 19 Rfa2 Qb7 20 Bd2 Ra8 21 Qa1 Rxa6 22 Rxa6 f6 23 exf6 Rxf6 24 h3 g5 25 Be1 Bc2 26 Ra3 Qf7 27 Bg3 Ba4 28 Bd6 Qg6

29 Rxa4 bxa4 30 Qxa4 Qe8 31 e4 Qd7 32 e5 Rf7 33 Bg4 Nd8 34 Qa8 Kg7 35 b5 Nb7 36 Qa6 Nxd6 37 exd6 Kg6 38 Qc6 h5

39 Bxe6 Qxe6 40 d7 Qxc6 41 bxc6 Resigns.

Source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 April 1885, page 108.

Mariano Eguiluz – Andrés Clemente VázquezNineteenth match-game, Mexico City, 1876

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d3 d6 6 a4 a5 7 O-O O-O 8 Bg5 h6 9 Bh4 Be6 10 Nbd2 Kh7 11 h3 g5

12 Bxg5 hxg5 13 Bxe6 fxe6 14 Nxg5+ Kg6 15 Nxe6 Qe7 16 Nxf8+ Rxf8 17 Kh2 Qe6 18 f4 exf4 19 d4 Nxd4 20 cxd4 Bxd4 21 Rb1 Ng4+ 22 Kh1 Nf2+ 23 Rxf2 Bxf2 24 Qc2 Rh8 25 Nf3 Bg3 26 e5+ Qf5 27 Qxf5+ Kxf5 28 exd6 cxd6 29 Rd1

29...Rc8 30 Kg1 Ke6 31 Nd4+ Ke5 32 Nb5 d5 33 Nc3 d4 34 Ne2 Rc2 35 Nc1 Ke4 36 b3 Bf2+ 37 Kf1 Be3 38 Nd3 Kf5 39 b4 axb4 40 Nxb4 Rf2+ 41 Ke1 Rxg2 42 Nd5 Rg1+ 43 Ke2 f3+ 44 White resigns.

Source: Análisis del juego de ajedrez by A.C. Vázquez, volume one (Havana, 1889), page 77.

Source: volume one of Análisis del juego de ajedrez

The final game takes us back to the quiz question at the start of the present item.

Andrés Clemente Vázquez – Mariano Eguiluz‘Fourth game of the first match’, Mexico City, 1875

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nc6 4 Bb5 Bd7 5 O-O Qe7 6 Nc3 O-O-O 7 d5 Nb8 8 Be3 a6 9 Bc4 f5 10 b4 h6 11 b5 f4 12 bxa6 fxe3 13 a7 exf2+ 14 Rxf2 Na6 15 Bxa6 bxa6

16 Qb1 Bg4 17 a8(B) Re8 18 Bc6 Bd7 19 Qb7+ Kd8 20 Qa8+ Bc8 21 Rb1 Qf7 22 Rb8 Ne7 23 Nxe5 Qxf2+ 24 Kxf2 dxe5

25 d6 cxd6 26 Qb7 Resigns.

Source: Análisis del juego de ajedrez by A.C. Vázquez, volume two (Havana, 1889), pages 36-37.

Vázquez explained that at move 16 White’s a-pawn could not be promoted to a queen because under the Mexican rules of the time, in the absence of an agreement to the contrary, promotion was possible only to a piece already captured.

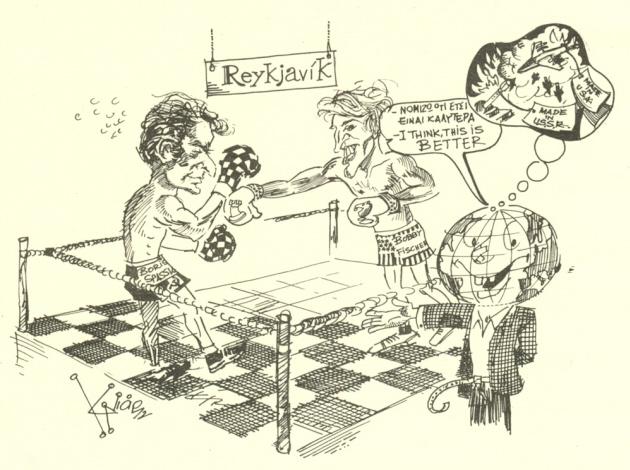

7037. Chess literature in Hellenic (C.N. 5612)

Michael Syngros (Amarousion, Greece) has updated his catalogue of ‘Chess literature in Hellenic (original or translations) and books by Hellenic authors in other languages’ and kindly authorizes us to make it available here.

This illustration comes from the multilingual cartoon book Η ζωή μας είναι σκάκι by Κώστα Νιάρχου/Costas Niarchos (Athens, 1972).

7038. Howard Staunton

Notes on the life of Howard Staunton by John Townsend (Wokingham, 2011) has just been published in a limited hardback edition of 100 copies.

The book also contains carefully-researched material about some secondary figures discussed in C.N., such as T. Beeby, F.M. Edge and J. Worrell.

7039. Starbuck

Alan Smith (Manchester, England) notes further games by Daniel Starbuck in the St Louis Globe-Democrat of 1881 (3 July, 31 July, 4 September and 11 September). Below is the shortest one, from the 4 September issue:

Daniel F.M. Starbuck – Max JuddSt Louis, 1881

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bd3 dxe4 5 Nxe4 Nxe4 6 Bxe4 Nc6 7 Nf3 Bd6 8 Be3 Ne7 9 a3 O-O

10 Bxh7+ Kxh7 11 Ng5+ Kg6 12 Qg4 f5 13 Qf3 Nd5 14 h4 Nxe3 15 Qxe3 Rh8 16 f4 Rh5 17 O-O-O Be7 18 g4 Rxg5 19 hxg5 Qd5 20 Qh3 Bxg5 21 Qh5+ Kf6 22 Qxg5+ Kf7 23 Rh7 Resigns.

Our correspondent points out that the Starbuck games can be consulted courtesy of the Jack O’Keefe Project at the Chess Archaeology website. It is a magnificent resource.

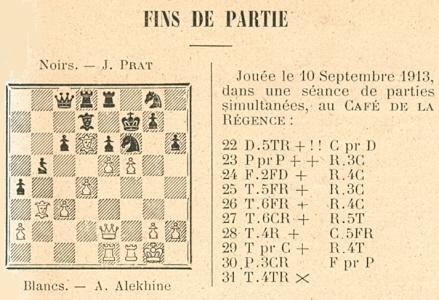

7040. Alekhine v Prat

Game 43 in Alekhine’s first volume of Best Games, against ‘M. Prat’, was described as ‘one of 20 simultaneous games played at Paris, September 1913’. The book was published in 1927; the German and Dutch editions brought out in 1929 identified Black as ‘J. Prat’ and did not stipulate the number of games in the exhibition. On the other hand, Deux cents parties d’échecs (Rouen, 1936) said that it was a 20-board display and that Black was ‘N. Prat’.

La Stratégie (October 1913, page 415) gave only the conclusion of the game and did not offer corroboration of Alekhine’s later statement that after Black’s 21st move he announced mate in ten:

As regards the number of players, 16 was the figure specified on page 360 of the September 1913 issue of the French magazine:

‘Le 10 septembre, également à La Régence, M. Alekhine conduit simultanément seize parties; avec une rapidité surprenante, il obtient le brillant résultat de quinze gagnées et une seule perdue contre M. le Dr de Hayes.’

7041. Who (C.N. 7021)

From right to left, Capablanca, Keres and Euwe, but then ...?

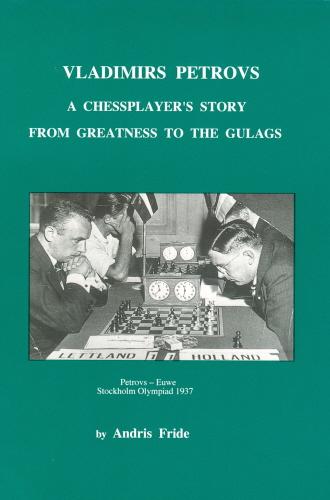

7042. Vladimirs Petrovs/Vladimir Petrov

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) notes two illustrated articles in Russian found via the Latvian website www.ves.lv:

7 Секретов (‘7 Secrets’), 29 November 2007 (page 10); PDF version.

Вести (‘Vesti’), 26 February 2009 (page 12); PDF version.

It may be recalled that in 2004 Caissa Editions published Vladimirs Petrovs A Chessplayer’s Story from Greatness to the Gulags by Andris Fride.

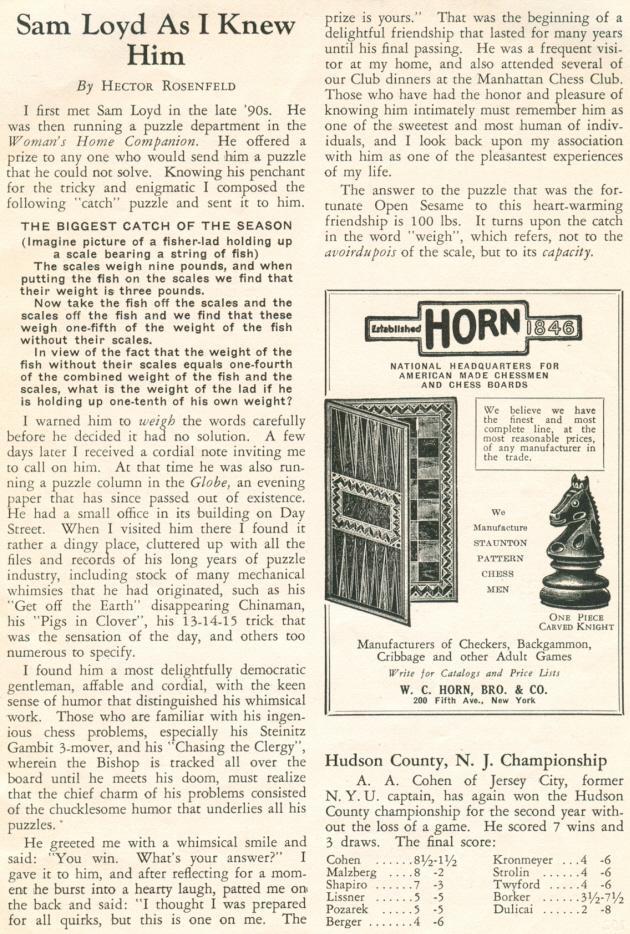

7043. A forgotten puzzler (C.N. 4923)

Concerning Hector Rosenfeld we add the article ‘Sam Loyd As I Knew Him’ from page 151 of the July 1935 issue of Chess Review:

7044. Eguiluz and Vázquez (C.N. 7036)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) has answered our request for information about Eguiluz v Vázquez games published in the latter’s books Algunas partidas de ajedrez (Mexico City, 1879 and 1880). Volume one gave all seven games of the first match, 21 of the 43 games from the second match, and 23 of the 35 games in the third match, whereas volume two had three offhand games between the two players (with no occasions specified).

Three of the four games in C.N. 7036 are in volume one. The Muzio Gambit game occurred in the second match (Mexico City, February 1876). Moreover, according to the book (pages 44-45) Vázquez resigned after 20 Re8. There is also a discrepancy regarding the Philidor’s Defence game in C.N. 7036; page 36 of volume one states that Black (Eguiluz) resigned after 23 Nxe5. The Bird’s Opening game in our earlier item is in neither Vázquez volume.

Below are four games from Algunas partidas de

ajedrez:

Second match, Mexico City, February 1876

Irregular Opening

1 e4 d6 2 d4 c6 3 f4 e6 4 Nf3 Be7 5 Bd3 d5 6 e5 Nh6 7 O-O g6 8 c4 f5 9 Nc3 Nf7 10 c5 h6 11 b4 g5 12 a4 Rg8 13 b5 g4 14 Ne1 Qa5 15 Bd2 Qd8 16 a5 Nd7 17 Qa4 Nb8 18 Nc2 a6 19 bxa6 Nxa6 20 Bxa6 Rxa6 21 Nb4 Ra7 22 a6 Qd7

23 axb7 Rxa4 24 b8(Q) Rxa1 25 Rxa1 Qb7 26 Ra8 Qxb8 27 Rxb8 Kd7 28 Na4 Bd8 29 Nb6+ Bxb6 30 cxb6 Nd8 31 Nd3 Nb7 32 Nc5+ Nxc5 33 dxc5 Rd8 34 b7 Resigns.

Source: volume one, page 45.

Mariano Eguiluz – Andrés Clemente VázquezThird match, Mexico City, 1877

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Bc5 4 Bg5 h6 5 Bh4 O-O 6 Nf3 d6 7 Nbd2 Be6 8 c3 g5 9 Bg3 Kg7 10 a4 a5 11 O-O Bxc4 12 Nxc4 Nh5 13 d4 Nxg3 14 fxg3 Ba7 15 Kh1 exd4 16 cxd4 f5 17 exf5 Rxf5 18 d5 Qg8 19 Qb3 Qxd5 20 Rad1 Qc6

21 Nfe5 Rxf1+ 22 Rxf1 dxe5 23 Nxe5 Qe8 24 Rf7+ Resigns.

Source: volume one, pages 59-60.

Mariano Eguiluz – Andrés Clemente VázquezThird match, Mexico City, 1877

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Bc5 4 Bg5 h6 5 Bh4 Nc6 6 c3 Na5 7 Bxf7+ Kxf7 8 b4 d5 9 bxc5 dxe4 10 Bxf6 Kxf6 11 Qa4 Nc6 12 dxe4 Qe7 13 Qa3 Nd8 14 c4 Rg8 15 Nc3 c6 16 Rd1 Be6 17 Rd6 Nf7

18 Nd5+ cxd5 19 Qf3+ Kg5 20 h4+ Kg6 21 Qf5 mate.

Source: volume one, page 63.

Mariano Eguiluz – Andrés Clemente VázquezMexico City (date?)

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 Bc4 Bh4+ 5 g3 fxg3 6 O-O gxh2+ 7 Kh1 d5 8 Bxd5 Nf6 9 Bxf7+ Kxf7 10 Nxh4 Rf8 11 d4 Kg8 12 Nc3 Bh3 13 Ng2 Nc6 14 d5 Ne5 15 Bg5 Neg4 16 Qd4

16...Nh5 17 Bh4 Qxh4 18 Ne2 Qg3 19 Nef4 Qxg2+ 20 Nxg2 Ng3 mate.

Source: volume two, page 24.

7045. Grading bonkers

A further article by G.H. Diggle, the Badmaster, from page 88 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It was originally published in the November 1982 Newsflash.

‘Is the Chess World gradually becoming (to paraphrase a famous utterance of Lord Hailsham’s) “Stark Staring Grading and Grandmaster Bonkers”? It would seem that Gradings and not Pawns (as Philidor once taught us) are now “the soul of Chess”. From some entertaining and controversial letters lately published in “a well-known chess periodical” it appears that at a recent weekend Tournament two ungraded players contrived to “get through the Customs”, and having infused themselves (like unleavened bread) into the midst of the graded, proceeded to add to their crimes by making very respectable scores. “Should not more Congresses”, enquires a perturbed reader, “have a special Section for ungraded players?” But this “apartheid” suggestion is torn apart in another letter by a “searing” satire on the alleged superior airs of the “graded ones” – “All ungraded players are despicable ... they should be thrown into the basement at Congresses and only allowed to play each other – so they’ll all stay ungraded – hee! hee!”

Nevertheless the first letter has a point, and is perhaps actuated not so much by any contempt for the “ungraded” as by the fear of lesser sections in Tournaments being spoiled by wolves in sheep’s clothing appearing from nowhere, modestly concealing their “fangs” when filling up their entry forms, and then showing “what big teeth they have got” by gobbling up their opponents (and the prize-money) “with every description of carnivorous enjoyment”. The letter also enquires, “Would you agree the proper place to get a grade is in a Club?” Certainly, if you are after one – but what about cantankerous old codgers like the BM who “don’t want no grade at their time of life” and object to seeing themselves priced on a list with the common herd and exposed to the humiliation suffered by “The Tin Gee-Gee” who was only marked one-and-nine while another was marked two-and-three. Is this haughty spirit and defiance of the closed shop to preclude the BM from jousting with graded genius, if he finds himself in the mood? It might be argued that this question is purely academic, as the BM has not played in a Congress for over 40 years. But just as a man is deemed by law to be capable of having issue at the age of 100, it is not to be ruled out that the BM might suddenly take it into his head to have a last fling and flicker across the Chess World like a stale meteor, throwing BCF Officials into some confusion by an entry form bearing such “recent results” as “Third Prize, Lincoln City Championship, 1932”. On such an entry being accepted (and it had jolly well better be) Identikit sketches of the BM would no doubt have to be posted on the Congress walls to safeguard against impostors of grandmaster strength (in collusion with the BM and in consideration of half the prize-money) taking his place in the “third class” or fourth if there is one.’

At the end of the following month’s article G.H. Diggle added a characteristically self-deprecatory erratum:

‘P.S. BM blunders again! (Newsflash, November ’82) He learns from “an unimpeachable source” that it was “The Toy Soldier” not “The Tin Gee-Gee” who was only marked one-and-nine. When will he verify his references?’

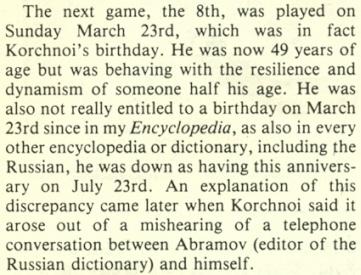

7046. Korchnoi’s date of birth

Further to the recent celebrations of Victor Korchnoi’s 80th birthday, Gábor Gyuricza (Budapest) asks why so many reference books give the master’s date of birth as 23 July 1931 instead of 23 March 1931.

Our correspondent observes, for example, that the July date is on page 177 of Shakhmaty Entsiklopedichesky Slovar edited by Anatoly Karpov (Moscow, 1990) and in the (impersonal) ‘Career Record 1947-1976’ on page 6 of Korchnoi’s book Chess is my Life (London, 1977). See also the third-person biographical notes in Viktor Korchnoi’s Best Games (London, 1978) and Korchnoi’s 400 Best Games by V. Korchnoi, R.G. Wade and L.S. Blackstock (London and New York, 1978).

We note that the mix-up was discussed in a report by Harry Golombek on the Korchnoi v Petrosian Candidates’ match on page 279 of the May 1980 BCM:

The ‘Russian dictionary’ was Shakhmatny slovar (Moscow, 1964); see page 257.

In 1981 Golombek brought out a paperback edition of his Encyclopedia. The Korchnoi entry duly corrected his date of birth from 23 July 1931 to 23 March 1931.

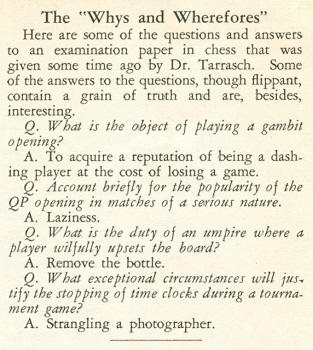

7047. Examination paper

From page 165 of the July 1935 Chess Review:

These responses by Tarrasch to an ‘examination paper’ are well known, having been reproduced by Fred Reinfeld on pages 291-292 of The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951) and on page 283 of The Joys of Chess (New York, 1961).

Where, though, did the item first appear?

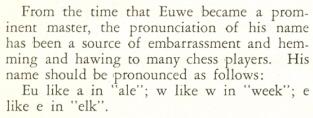

7048. Pronouncing Euwe (C.N. 7019)

A particularly dubious suggestion for pronouncing ‘Euwe’ was given on page 274 of the December 1935 Chess Review:

The proposal was repeated on page 262 of the magazine’s November 1937 issue.

7049. Best games

On page 232 of the August 1970 BCM Wolfgang Heidenfeld wrote:

‘... a phrase like “Alekhine’s Best Games” is really ambiguous: it may mean two entirely different things, viz. (a) the games Alekhine played best and (b) the objectively best games in which Alekhine was a participant (in which the standard of the game is achieved by both partners) – thus he need not necessarily have won them. This, in fact, is the basis of my anthology Grosse Remispartien.

In fact, it is little short of ludicrous that Alekhine’s Best Games does not contain his draw against Marshall at New York, 1924, where a most original and new strategic conception by Marshall is met by an amazing tactical finesse of Alekhine’s, the whole (drawn) game being one of the greatest ever played. It is similarly ludicrous that Golombek’s anthology of Réti’s Best Games is without his draw against Alekhine at Vienna, 1922 – which has been christened the Immortal Draw and which even Alekhine does not pass over in his own collection. Similarly some game collections of Tal’s are deprived of the fantastic draw against Aronin at the 24th Soviet championship (Moscow, 1957) – a game of which Keres stated in a much-acclaimed article that one could not do justice to Tal’s achievement in that tournament without coming to grips with it.’

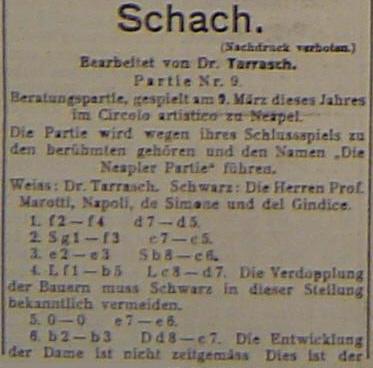

7050. Tarrasch v the Allies (C.N.s 5162 & 6279)

White played 31 Bc7

Richard Forster (Zurich) points out that the game was given with Tarrasch’s notes on page 4 of the second part of the Züricher Post, 22 March 1914:

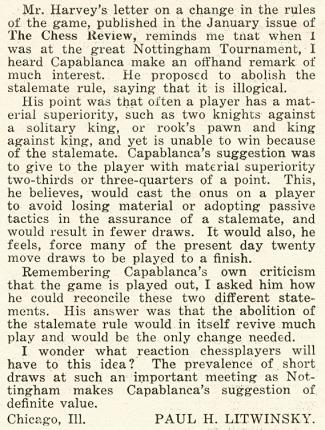

7051. Changing the rules

In a letter on page 7 of the January 1937 Chess Review Herbert Harvey proposed a rule change whereby a pawn would ‘become by promotion automatically the piece appropriate to the file on which it is promoted’. A choice of pieces would exist only in case of promotion on the king’s file.

On page 29 of the following month’s issue Paul H. Litwinsky (later: Paul H. Little) related an ‘offhand remark’ by Capablanca at Nottingham, 1936, regarding stalemate:

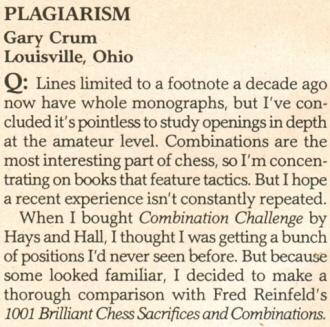

7052. Hays and Hall (C.N. 6886)

Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA) has found that the wholesale copying perpetrated by Combination Challenge! was briefly mentioned in a contribution by Gary Crum to Larry Evans’ column on pages 18-19 of the December 1994 Chess Life:

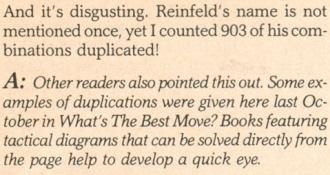

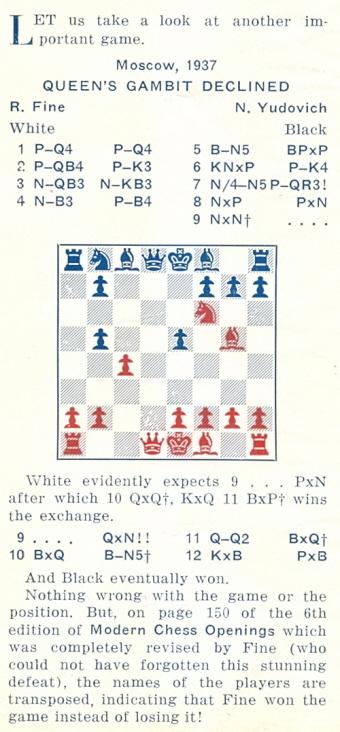

7053. Fine v Yudovich

From ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’ on the inside front cover of the October 1951 Chess Review:

A correspondent (Edward J. Tassinari, Scarsdale, NY, USA) referred to Irving Chernev’s feature in C.N. 966 (see page 152 of Chess Explorations). The sixth edition of Modern Chess Openings was published in 1939; as pointed out on page 144 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004), Fine correctly named himself as White in his later book Practical Chess Openings (Philadelphia, 1948). See page 189. (Page 147 of Woodger’s book published, with notes by Yudovich, the complete score of Fine v Yudovich, which ended 43 Kg5 Ke5 44 White resigns.)

We add that Fine also gave an accurate attribution of the game in an article ‘My Moscow Impressions’ on pages 102-103 of the May 1937 Chess Review (a translation from 64):

7054. ‘The Little Capablanca’ (C.N. 6365)

When Reuben Fine won the 1944 US Lightning Championship (playing, at ten seconds per move, 22 games in a single day), he dropped only one point, in this game:

Julius Partos – Reuben FineNew York, 25 June 1944

King’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 Nf3 O-O 5 e4 d6 6 Bd3 Nbd7 7 O-O e5 8 dxe5 dxe5 9 Bc2 c6 10 Bg5 h6 11 Bh4 Qe7 12 Qe2 Nc5 13 Bg3 Nh5 14 Rad1 Ne6 15 Qd2 Nd4 16 Nxd4 exd4 17 Ne2 Rd8 18 Bd3 Be6 19 f4 Nxg3 20 Nxg3 Bg4 21 Rde1 Bd7 22 e5 Re8 23 Ne4 c5 24 Nd6 Reb8

25 f5 Bxe5 26 fxg6 Qxd6 27 Qxh6 Be6 28 gxf7+ Bxf7 29 Qh7+ Kf8 30 Qxf7 mate.

Source: Chess Review, June-July 1944, page 12.

Partos, who finished sixth in the tournament, also inflicted defeats on Kevitz and Denker, as well as drawing with Kashdan. See the coverage on pages 53-69 of The Year Book of the United States Chess Federation 1944 edited by Montgomery Major (Chicago, 1945). Page 58 commented regarding Partos v Fine:

‘Fine’s only loss; and seldom has the Champion been so completely outgeneraled.’

The game was also given in Partos’ obituary on pages 148-150 of the May 1969 Chess Review. He was described as a ‘phenomenon’ who was playing chess at the age of five (‘sometimes with Mrs Mary Bain, who was then living in the same apartment house’) and performed his first simultaneous exhibition when only 11. In blitz chess, the obituary suggested, he was second only to Fine.

A snippet regarding Chicago, 1937, from page 203 of the September 1937 Chess Review:

‘The supreme note of self-confidence was struck by Partos, who sat through a rook and pawn ending blithely reading a tabloid newspaper while Barnie Winkelman, only the author of Modern Chess Endings, tackled the position. For this feat Partos received the epithet of “Little Capablanca”.’

The Chess Review obituary in 1969 gave Partos’ birth-date as 26 January 1915, and that information appeared in Jeremy Gaige’s A Catalog of USA Chess Personalia (Worcester, 1980). However, Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) had 26 July 1916, and the privately-circulated 1994 version made another change, to 26 July 1915.

Partos’ best-known game is probably his win over V. Harris in the 1951 Colorado State Championship, being featured on pages 225-227 of Pawn Power in Chess by Hans Kmoch (New York, 1959).

The concluding paragraph of Jack Straley Battell’s tribute to Partos on page 148 of the May 1969 Chess Review stated:

‘Also, Julius composed a special brand of chess problem, “Reconstructions”. In it, he gave the solution to a composed endgame, and the “problem” was to reconstruct the problem position.’

7055. Alekhine v Keres

C.N. 847 asked about the exact moves of the famous game Alekhine v Keres, Munich, 1942. After 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 c4 Bb7 4 g3 e6 5 Bg2 Be7 6 O-O O-O 7 b3 d5 8 Ne5 c6 9 Bb2 Nbd7 10 Nd2 ...

... the question posed was whether play went 10...c5 11 e3 Rc8 12 Rc1 Rc7 (Gran Ajedrez, 107 Great Chess Battles, Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-45) or 10...Rc8 11 Rc1 c5 12 e3 Rc7 (books on Alekhine by Kotov and Müller/Pawelczak).

On page 268 of Chess Explorations we remarked that when annotating the game on pages 143-144 of the 1 October 1942 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter Alekhine gave 10...Rc8 11 Rc1 c5, contrary to the move order in his (posthumous) book Gran Ajedrez. Moreover, in the German magazine Alekhine stated that the opening moves were 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 d4 Bb7, whereas Gran Ajedrez indicated 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 c4 Bb7.

This photograph of Alekhine and Keres was taken a few months earlier, at Salzburg, 1942:

Source: Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943), page 273.

7056. N. Falkbeer

‘The following excellent position, we understand, is the first production of Herr N. Falkbeer, of Vienna, a brother of the celebrated chessplayer.’

Source. Page 60 of the Chess Player’s Magazine, August 1863.

When the problem was given on page 247 of the August 1863 Deutsche Schachzeitung, the forename Nicolaus was provided. Elsewhere, the spelling Nikolaus is found. See, for example, page 1 of volume one of Schachmeister Steinitz by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1925), which stated that he was a tax officer: ‘der Steuerbeamte Nikolaus Falkbeer (Bruder Ernst Falkbeers)’.

7057. The Lasker odds anecdote

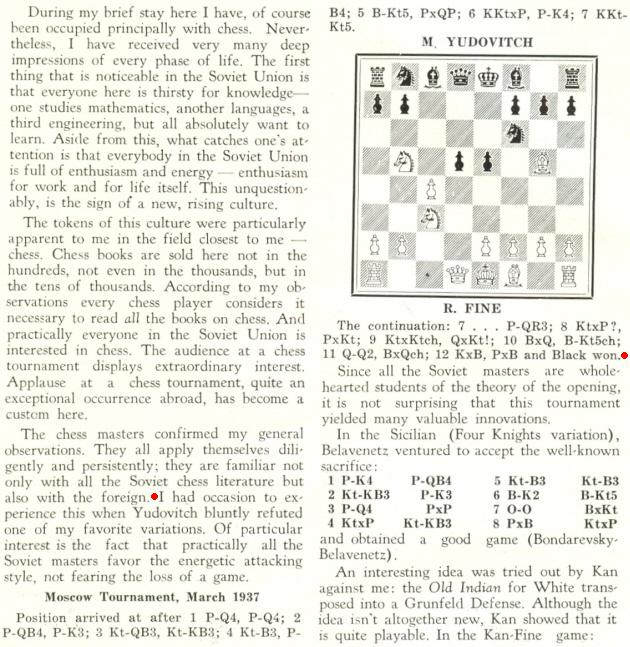

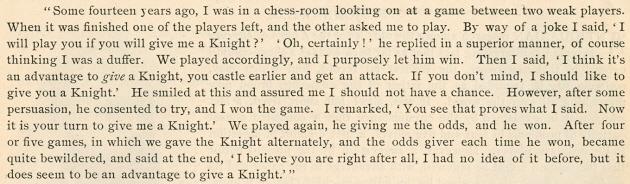

For insouciant story-telling purposes there exists an ideal anecdote: the oft-related one about how Emanuel Lasker, unrecognized, intentionally lost one or more handicap games to N.N. but then turned the tables, thereby convincing his opponent that giving odds is an advantage. The setting and dialogue can be whatever the story-teller wants, in the interests of A Fun Read.

The yarn appeared on, for instance, pages 200-201 of Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984), but we are particularly intrigued by the wording on pages 4-5 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

As Alan Slomson pointed out on page 145 of the 30

December 1969 CHESS, the following contribution by

Antony Guest appeared on page 111 of The Chess Bouquet

by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897):

Alan Slomson commented:

‘Guest says this happened “some 14 years ago”, when Lasker would have been only 15 years old.’

The similarity of the wording in the Chernev and Guest texts prompts a basic question: when was Lasker’s name first introduced into the story?

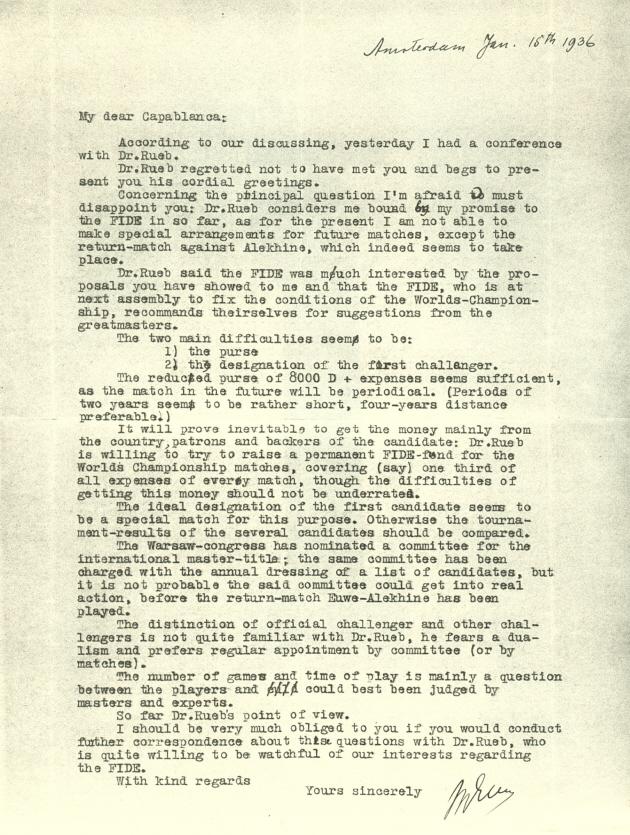

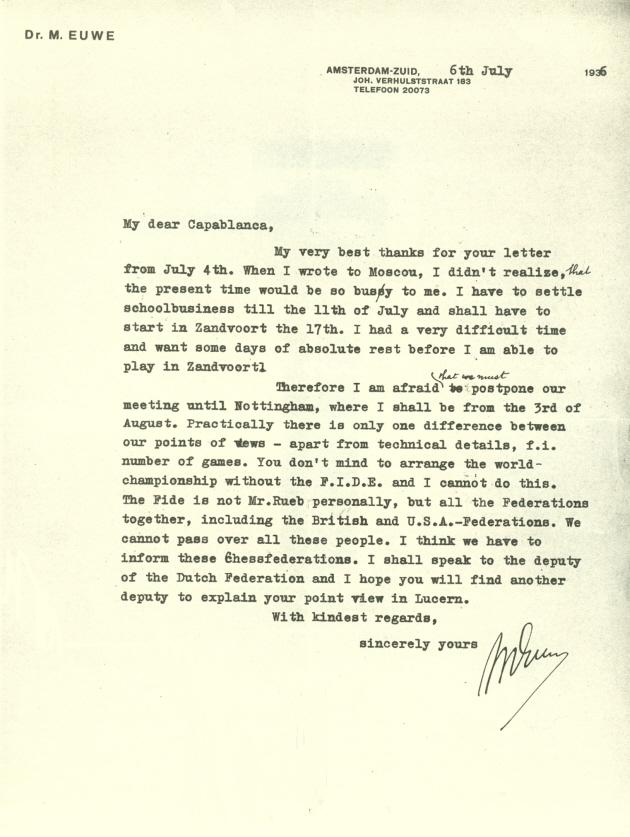

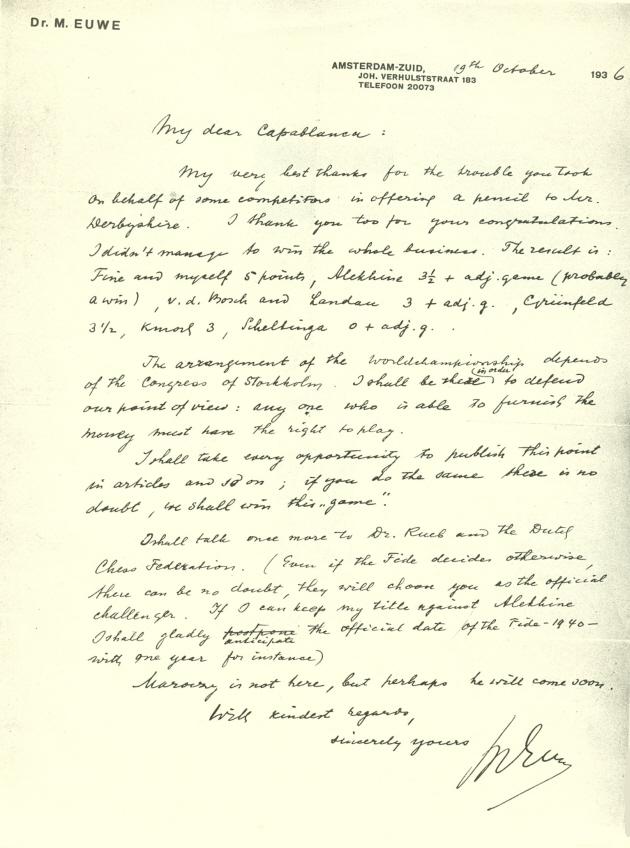

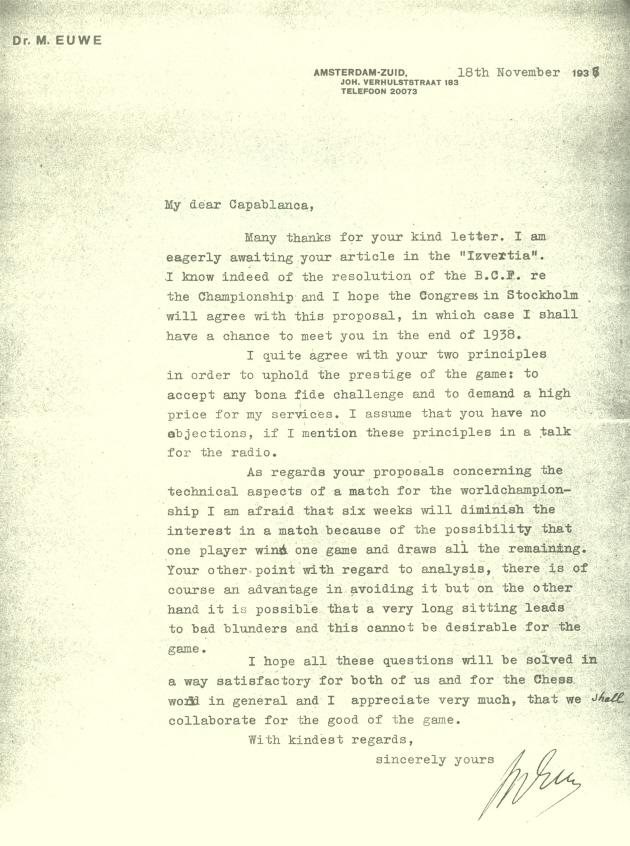

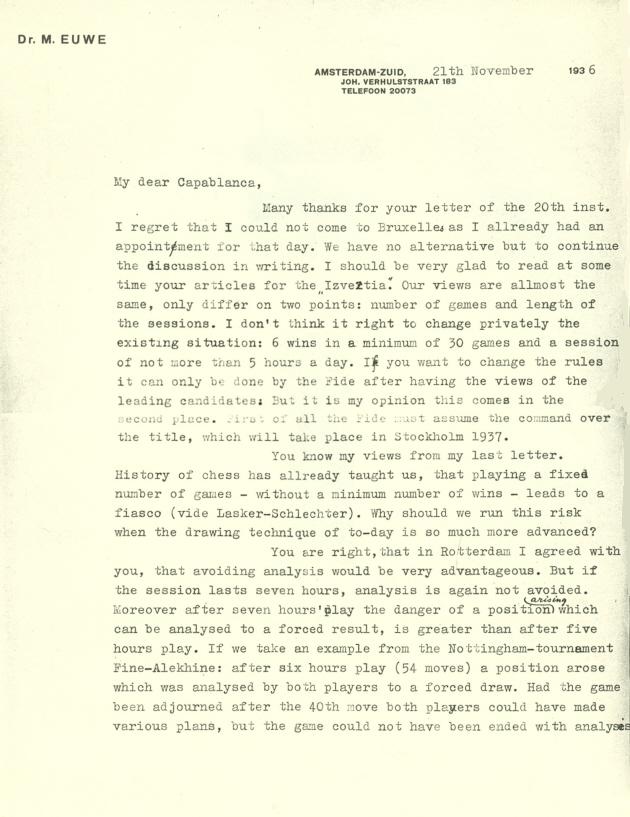

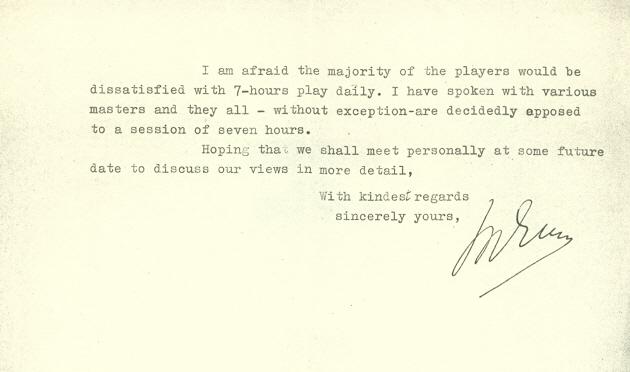

7058. Euwe letters to Capablanca

Our archives contain copies of five letters written by Euwe to Capablanca in 1936:

7059. Janowsky pearl

C.N. 6683 referred to the Pearl of Zandvoort, but a less familiar term occurs on page 61 of One Move and You’re Dead by Erwin Brecher and Leonard Barden (London, 2007). The conclusion of Janowsky v Schlechter, London, 1899 is given, with the comment that White ‘forced checkmate with such an impressive move that they called it The pearl of St Stephen’s after the London hall where the tournament was played’.

Wanted: other sightings of the term.

The game ended 34 Qxh7+ Kxh7 35 Rh5+ Kg8 36 Ng6 Resigns.

7060. Who? (C.N.s 7021 & 7041)

We are grateful to a number of readers who attempted to identify the figures in the airport photograph. The key is provided by a cutting in our archives from the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf in November 1938 (exact date unavailable):

7061. Julius Partos (C.N. 7054)

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) reports that he has found the Partos family in the United States Federal Census of 1920 and 1930. In the latter case, the spelling throughout was ‘Bartos’. The family was resident in New York, but Julius’s father, Joseph, was born in Hungary circa 1878.

The censuses indicated Julius’s age as five and 15 respectively. Mr Miller comments that, since 2 April 1930 was the date of the latter census, 26 January 1915 is the most probable birth-date of the three cited in C.N. 7054.

Another game:

A.N. Towsen (London Terrace Chess Club) – Julius Partos (Queens Chess Club)New York Metropolitan League, 1947

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 O-O 6 Nf3 Nbd7 7 Rc1 b6 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Qa4 c5 10 Qc6 Rb8 11 Nxd5 Nxd5 12 Qxd5 Bb7 13 Bxe7 Qxe7 14 Qc4 Bxf3 15 gxf3 cxd4 16 Qxd4 Ne5 17 Be2 Rbd8 18 Qa4 Qf6 19 f4 Nd3+ 20 Bxd3 Rxd3 21 Rc2 Qg6 22 Ke2 Rfd8 23 Re1

23...Rxe3+ (‘24 Kxe3 and 24 fxe3 both run into quite unusual epaulette mates.’) 24 Kf1 Rxe1+ 25 Kxe1 Qg1+ 26 Ke2 Qd1+ 27 Ke3 Qd3 mate.

Source: Chess Review, May 1969, pages 148-149.

7062. Vuković v N.N.

Information is sought on this game:

The finish was 1 Nf5 Qxh4

2 Qh5 and Black resigned.

Page 125 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949) merely stated that ‘Vuković won this from an amateur, in 1937’. Walter Korn gave the position on page 69 of The Brilliant Touch (London, 1950) with the heading ‘Simultaneous, 1937’.

So far we have not found a reference to the venue, let alone the identity of Black and the full game-score.

| First column | << previous | Archives [81] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.