Edward Winter

Few chessplayers today, even in the United States, recall the name of D.A. Mitchell, yet for a period he was one of the country’s most prominent writers on the game. In addition to his own books, in 1917 he was charged with bringing out a ‘corrected’ version of Emanuel Lasker’s Common Sense in Chess, a fact which testifies to his standing at the time. Yet his writing career was short. In early June 1926, while still only in his early 40s, he vanished, never to be seen again. Newspapers reported/speculated that he had been the victim of mental disturbances and had killed himself.

David Andrew Mitchell was born in Philadelphia on 27 December 1883. It was in 1912 that his journalism began to attract attention, and the following paragraph appeared on page 233 of the October 1912 American Chess Bulletin:

‘The Philadelphia Ledger has again decided to devote a certain amount of space weekly to chess, and we understand that the conduct of this department has been entrusted to David A. Mitchell, also chess editor of the Hartford Courant.’

A similar report appeared a couple of years later, on page 246 of the November 1914 Bulletin:

‘We are pleased to note that the Public Ledger of Philadelphia has resumed publication of a weekly chess column in its Sunday supplement. Usually, the best part of a page is devoted to the department, which is in charge of David A. Mitchell, erstwhile chess editor of the Hartford Courant. Mr Mitchell, who has made a name for himself as a composer of problems, is keenly energetic in the advancement of Caissa’s cause, as witnesses the establishment of a similar department in Country Life, also published in Philadelphia. Here, too, Mr Mitchell is at the helm.’

However, his principal fame as an author resulted from the two standard beginners’ works Mitchell’s Guide to the Game of Chess (1915) and Chess (1917). Both went through a number of editions, and the Guide, which was published by David McKay, Philadelphia, was still appearing in the 1940s.

The Introduction to the original Guide opened with an affectedness that Mitchell was soon to abandon:

‘Young Mr Student, permit me to introduce you to old Mr Chess, but before doing so let me warn you that the old gentleman will seem at times rather complex and extremely hard to know. After having become acquainted with him, however, you will find that, like most tried and true friends, he will be the means of giving you many a pleasant hour, and the longer you are associated with him, the greater will become your desire to know him better.’

The Introduction concluded:

‘In the many years that I have been associated with Mr Chess I have valued his friendship above all others. Besides helping me forget my troubles, fancied and real, he has led me into the circle of good fellowship the world over, to which only those who know him have entrée.’

It was no masterpiece, but Mitchell’s Guide was mostly clear and accurate. One of the few eccentricities was the advice on page 37: ‘When in doubt, move the king’. The annotated games section concentrated on the output of ‘the greatest of all annotators, Dr Sigmund [sic] Tarrasch’, and the work finished with seven compositions, six of them by Mitchell himself. The one below was headed ‘End-game study’, even though, as the book notes, it is a mate in eight:

Solution: 1 Nf2+ Qxf2 2 Qb1+ d3 3 Qb4+ d4 4 Qb7+ Nd5 5 Qh7+ Qf5+ 6 Kg3+ Nf4 7 Qb7+ Rc6 8 Qxc6 mate.

A revised edition of Mitchell’s Guide was issued by David McKay in 1920 and included a collection of Marshall’s best productions which was ‘unique in that the games were selected by the champion himself as being those which appeal especially to him, out of the thousands he has played’. It is of historic interest to note Marshall’s favorites and the corresponding comments thereon.

In the 1930s Mitchell’s Guide was reprinted several times in paperback, with the sub-heading ‘a complete course of instruction for beginners’. Then in 1941 it was substantially revised by Edward Lasker, still without providing any personal information about Mitchell, who had last been seen 15 years previously. The Guide had evidently become something of a classic, for it is rare to find a beginners’ primer revised by a prominent master. Lasker wrote in the Preface:

‘Mitchell’s guide to the game was written just a few years before the weight of modern chess ideas made itself felt in chess contests throughout the world. In this new edition the publishers therefore considered it best to offer a complete revision which might serve as an elementary text book for the student of modern chess.’

The Lasker revision was also used as the chess part of A Guide to Chess and Checkers by David A. Mitchell and Lawrence Held (The World Publishing Company, Ohio and New York, 1941).

Mitchell’s other chess book, simply entitled Chess, was first issued by The Penn Publishing Company, Philadelphia in 1917 and was dedicated to Rudolph Blankenburg. It proved less enduring than the Guide, even though the title page sang out:

‘The best beginners [sic] manual ever made. The book is a model of clearness. There are many excellent diagrams and scores of problems.’

The problem section was substantial, with 75 compositions, and the work concluded with an account of four-handed chess and a brief history of the regular game. The book again showed Mitchell’s interest in the career of Marshall, and pages 76-78 gave a game Eddy v Marshall: ‘Frank J. Marshall recently encountered A.J. Eddy, a well-known chessplayer from Chicago, at the rooms of the Manhattan Chess Club, New York City, in a series of games, the object of which was to test the Queen’s Gambit Declined opening.’ Little seems to have been recorded elsewhere about this event.

Chess had a companion volume, Checkers, from the same author and the same publisher. First published in 1918 and dedicated to Walter Penn Shipley, Checkers stated on its title page: ‘An expert explains all the moves of the game, its openings and positions, and gives many problems’.

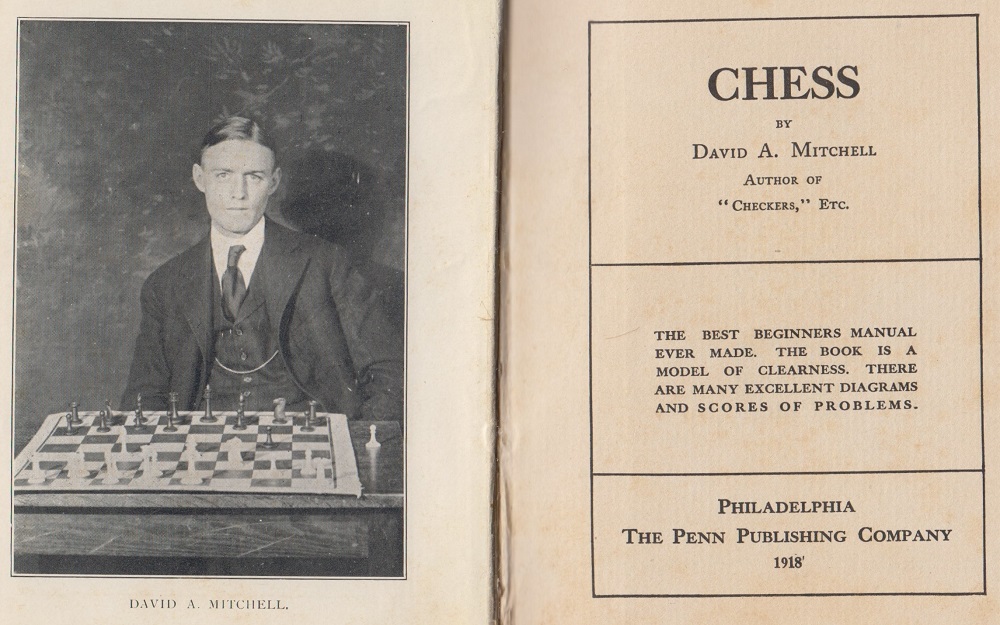

David Andrew Mitchell

Even during Mitchell’s lifetime, chess magazines had relatively few mentions of him. One exception came after Marshall gave a huge simultaneous exhibition (+97 –9 =23) at the great Auditorium of the Curtis building in Philadelphia on 26-27 December 1916. The event was ‘due to the courageous initiative and hard work of David A. Mitchell, chess and checkers editor of the Public Ledger’ (American Chess Bulletin, February 1917, page 25). On pages 66-67 of Chess Mitchell recorded that at the display Marshall ‘adopted the Danish Gambit on every table wherever it was possible for him to open with this style of game’.

Page 26 of the February 1917 Bulletin had a personal news story:

‘Not long after the great chess drive, David H. [sic] Mitchell consummated the most important deal in his life, which culminated in his marriage to Miss Hannah E. Williams, of Philadelphia, on 13 January. It was the end of a romance that started 14 years ago, when the bride-to-be was but eight years old, and, indirectly, chess was responsible in bringing about the happy union.’

This was followed by an account in Mitchell’s own words:

‘John Buckley, of 830 Corinthian avenue, my old chess master, was a friend to all children. Hannah Williams lived in the next house. She was often entertained by Mr Buckley with several other children, but on the evening that Mr Buckley played chess, of course, the little folks had to forego their evening at the Buckleys’. It was “the old chessplayer” as I was called by the children, who spoiled their evening’s amusement on more than one occasion. By and by, Hannah grew up to think more of the old chessplayer, until, after 14 years, we were married at St Mark’s Lutheran Church. If I had not been asked to visit Mr Buckley to play a game of chess, I would never have met my little wife.’

Little further mention was made of Mitchell in the Bulletin until the following paragraph was printed on page 9 of the January 1926 issue:

‘David A. Mitchell, former chess editor of the Philadelphia Ledger, who has been residing in New England for his health, has moved to Bermuda, where, on Harrington Sound, he finds the climate very mild and expects to spend the winter there.’

A few months later, the newspapers reported Mitchell’s mysterious disappearance. For example, the [Philadelphia] Evening Ledger of 2 June 1926 gave the following account:

‘D.A. MITCHELL DISAPPEARS:

WRITER OF BOOKS ON CHESS

Former Philadelphian Vanishes From

Summer Home in MaineNorthport, Me., June 2 – (AP) – David A. Mitchell, formerly of Philadelphia, and author of several books on chess, has been missing from his summer home on Temple Heights here since Sunday night. A searching party was organized by Sheriff Frank D. Littlefield today after a note was found at the house.

Mr Mitchell, it was learned, called on a neighbor Sunday night and gave him a check for $25, saying it was all he had and he never would need any more. He returned on 15 March from Bermuda, where he passed the winter.

Mr Mitchell was a chess writer for Philadelphia newspapers for eight years. Several years ago ill health forced him to go to Raymond, N.H., where he lived in a bungalow that overlooked a lake.

He has been regarded as one of the greatest chess authorities in this country. While in Philadelphia he promoted several big tournaments, one of them being a marathon event, in which David C. [sic] Marshall, then the United States champion, met all comers.’

The following is from the Philadelphia Inquirer of 3 June 1926:

‘PHILA. MAN MISSING

Search Being Made in Maine Woods

for David A. Mitchell

Special to The InquirerBELFAST, Me., June 2 – Sheriff Frank A. Littlefield and a posse searched the woods on Mount Percival, Northport, Maine, for David A. Mitchell, a Philadelphia newspaper man, who has for the past few years occupied a home near the mountain.

Mitchell was last seen Sunday night when he told callers at his home it was the last time they would ever see him and that he was suffering mentally. He had talked of hearing beautiful but mysterious music, and on a card found on his desk was written, “If he don’t stop that machine I’ll go insane”. Mitchell spent the past winter in Bermuda, returning in March to Northport, and is said to be despondent over the death of his mother a few weeks ago. He has one brother, William L. Mitchell, of Philadelphia. While his house was in perfect order, he took none of his belongings and it is feared he may have drowned himself in Penobscot Bay.’

Acknowledgement for copies of the above-quoted Philadelphia newspapers: Jeremy Gaige of Philadelphia.

(Chess Café, 2000)

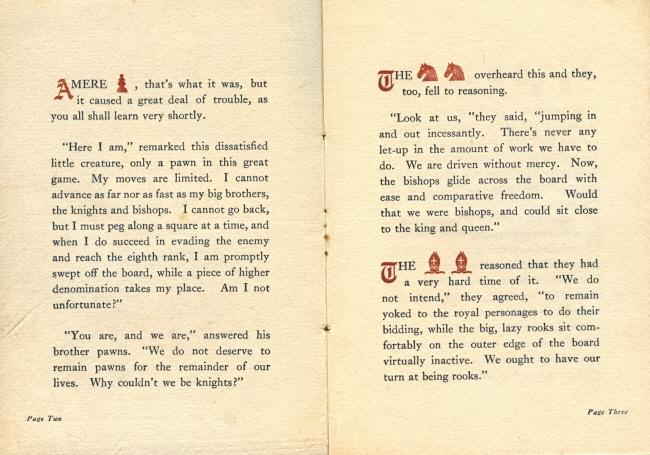

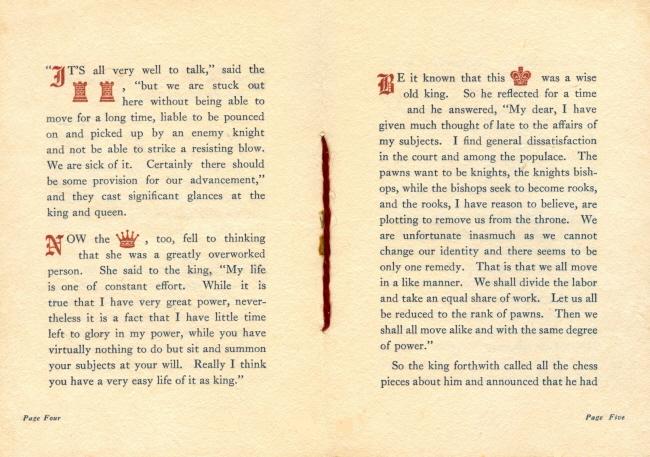

Below, from C.N. 5518, is the full text of Mitchell’s very scarce booklet Fable of the Discontented Chessmen (Philadelphia, 1918):

Russell Miller (Camas, WA, USA) provides some additional biographical information gleaned from Ancestry.com.

The 1900 Federal Census (Philadelphia Ward 15, Philadelphia, PA) stated that David Andrew Mitchell, aged 16, was living with his parents William Mitchell (who was born in Ireland on 2 February 1836 and emigrated to the United States in 1854) and Isabella F. Mitchell (born in Ireland on 27 April 1848 and emigrated to the United States in 1858).

David Mitchell’s Draft Registration Card for the Great War (15 September 1918, Chester County, PA) gave his occupation as ‘Editor, Public Ledger’ and his employer as Cyrus Curtis. Some personal details were also included: ‘Height: Tall. Build: Slender. Eyes: Blue. Color Hair: Light.’

(5810)

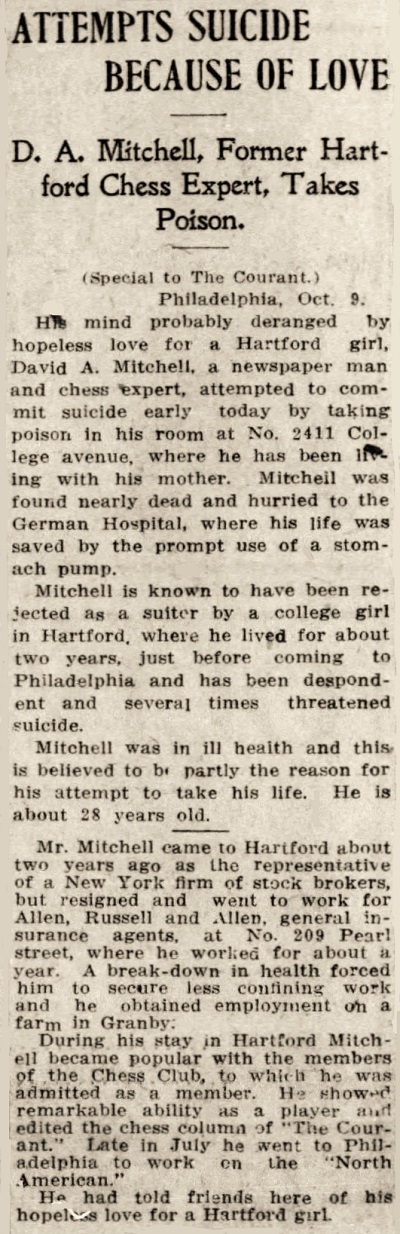

From page 1 of the Hartford Courant, 10 October 1912:

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.