Edward Winter

(2005, with updates)

‘I announce my retirement from chess.’ That laconic would-be bombshell somehow failed to jounce the chess world off its axis when published, under the heading ‘Flamboyant Exit’, on page 107 of CHESS, 4 December 1964. The full text of the letter to the editor is given below:

‘I announce my retirement from chess, as from 24 November 1964.

David Mabbs

Harrow, 21 November 1964

P.S. – Please – no more tempting circulars!’

In Linares on 10 March 2005 Kasparov’s declaration of retirement from professional chess was far more of a bomba, and, unlike Mr Mabbs, he will certainly receive many a tempting offer to recant his decision. For now, though, he goes down in history among those world champions whose careers ended on a sombre note, i.e. all of them.

After enjoying a decade and a half of pugnacious pre-eminence, Kasparov lost a matchlet to Kramnik in Hammersmith, London in 2000 through atypically listless play, after which his supporters, and then others, took to describing him not as ‘the former world champion’ but, on account of his rating, as ‘the world’s number one player’. It was an Elo-inspired variation of the description of Capablanca on the title page of the US edition of his 1935 book A Primer of Chess: ‘World’s foremost chess expert’.

In the late 1990s FIDE was favouring rapid play, knock-out tournaments, mini-champions and, more generally, whatever flew in the face of chess tradition. In the meantime, the top masters were left to their own devices. At first they indulged in tractations about a new world championship cycle, with each potential contender seeing any anticipated personal benefit as a birthright and any putative personal disadvantage as an affront. But was it all really necessary? If a direct re-match had been organized between Kramnik and Kasparov, without any qualification system, the other leading lights would, of course, have complained long and hard, yet Kasparov’s status was incomparable and anno Domini was becoming a factor.

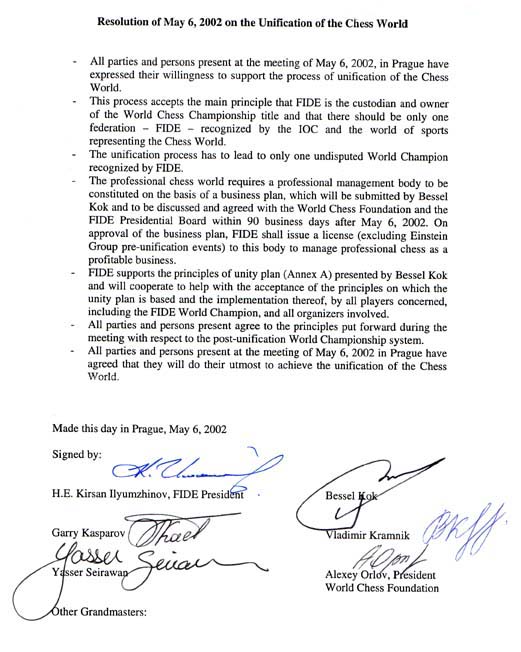

Qualifying matches were projected, announced and abandoned, but in May 2002, 18 months after the Hammersmith débâcle, the seemingly impossible was achieved in Prague with the thrashing-out and signing of a Resolution ‘on the Unification of the Chess World’. Although a compromise which fell short of Yasser Seirawan’s original proposal, it became the only realistic prospect of bringing about a match for the undisputed world championship.

Throughout that process, steered by Seirawan, Kasparov conducted himself better than most and better than usual. All the signatories undertook to ‘do their utmost to achieve the unification of the Chess World’, but ‘utmost’ is an undefinable word. More qualifying matches were projected, announced and abandoned, and when the Resolution eventually wilted away into limbo Kasparov was the most aggrieved party. Some of his detractors no doubt viewed this as his come-uppance, and it could indeed be regarded as the culmination of events which he himself had set in train during the nadir of his chess career, i.e. the break-away from FIDE in 1993. That episode, which has caused world championship bedlam for a dozen years, was seen as an obvious calamity by any level-headed observer at the time. To Kasparov, however, the reality did not sink in until much later: on page 13 of the 2/1999 New in Chess he described the founding of the PCA in 1993 as his biggest mistake of all.

A pattern can be discerned which takes us to the heart of how Kasparov’s off-the-board career went off the rails and how his personal reputation slumped from unparalleled heights. Until the mid-1980s he was widely regarded as the unimpeachable golden boy of chess, the fresh newcomer/victim/anti-Communist who stood in such stark, attractive contrast to Karpov. Increasing shifts of opinion against Kasparov were detectable from 1985 onwards, but it was not until 1987, and the publication of his autobiography Child of Change, a deeply untrustworthy shambles, that the real deterioration in his public standing began. Kasparov failed to realize that if a book of his repeatedly made statements which did not add up, including vicious scatter-gun attacks, readers would notice and some of them would even say so publicly. For him, however, this was another epiphany which came far too late. (On page 49 of the 1/1990 New in Chess he acknowledged what all but the oiliest sycophant had recognized since the year of the book’s publication: ‘I deserved the critical reception of Child of Change.’)

In the above-mentioned 1999 issue of New in Chess Kasparov added that he had made ‘so many mistakes’ and that ‘many things went wrong, both in business and in chess’. Such breast-beating, a rarity for a chessmaster with a jumbo ego, prompts a simple question: why has he been so prone to making so many mistakes that were so easily identifiable and avoidable? The explanation, we believe, is a fil rouge through his chess career: singularly poor personal judgement (aggravated by hot-headedness) which not only causes gaffes of all kinds but also makes him incapable of selecting an appropriate entourage to help protect him against recurrences. Nobody was there to persuade him in 1993 that his urge to abandon FIDE would occasion almost universal condemnation. Nobody convinced him in 1986-87 that publication of Child of Change was an insult to the intelligence of any reader and would, sooner or later, do untold harm to his own reputation. Nobody ensured that he steered clear of cheap literary associations with can’t-learn-won’t-learn writers. Nobody has made him see, even today, that his moribund ‘chesschamps’ website, about which he was formerly so enthusiastic, would be unworthy of a junior fan, let alone a figure of his standing. The Predecessors series is a further example of how Kasparov’s passion for truth and the highest standards at the chess board has difficulty in spreading elsewhere. Before volume two had even been published he was showing (limited) contrition over what had gone so badly wrong with volume one and how amends might be made in a revised edition. But why did he receive no proper counsel on that high-profile project before anything at all was published?

Whereas Fischer, even during his periods of relative mental steadiness, viewed attempts to befriend or assist him with narrow-eyed paranoia, Kasparov’s failure has been at the opposite extreme and has, down the years, enabled some spectacularly unsuitable individuals to work their way in as neo-associates and pseudo-friends. A master with Kasparov’s star quality and marketability inevitably has to endure many opportunistic approaches from those wanting a seat in the inner circle, and, in his own interests, he should have obstructed each new arrival on the threshold with an inquisition which began: ‘Halt. Who goes there? Friend or leech?’

Who, if anyone, gave Kasparov helpful advice over his wish to abandon professional chess is impossible to know. There will be a widespread yearning for him to resume, one day, a chess career of some kind, for it seems improper and unwarranted that lovers of the game, and not least in future generations, should be denied any brilliancies by him bearing a date later than 2005. It must be hoped that, at a moment of his own choosing and properly advised, this chess genius but deeply flawed man will revoke a retirement announcement which – in terms of his age, at least – is the equivalent of Emanuel Lasker folding up his board in 1910.

(3648)

From Mig Greengard (Brooklyn, NY, USA):

‘A few words regarding your interesting note about Garry Kasparov and his retirement. While I don’t disagree with the content of your item, Garry has always been demonstrably impetuous and I’m a little surprised you give much credit to an entourage of Iagos and people trying to make a buck off of him. They may exist, to a degree, but he makes his own decisions, often with what I consider too little external input. That, and his mother is still very much the only real member of the inner circle, or at least the “inner inner” circle.

In the brief time I have been close to him, most of his big decisions, dubious and otherwise, were made quickly and on his own. (Obviously the degree of his mother’s influence is unknown to me.) His sudden decision to dive into politics last year with the Committee 2008 Free Choice was against the advice of just about everyone. This was also true with his retirement. In both cases it was more after the fact concern than pre-announcement advice. Certainly in my case, as a selfish chess fan, I would much prefer he played chess until, at least, his best isn’t good enough. I’ve encouraged him to stay involved in the chess world by writing a column or training young players, and I expect he will eventually return to the board.

You can make a case that his combative, contrarian nature tends to lead him against the advice of friends and public opinion because he enjoys trying to prove people wrong. (I believe this largely explains his interest in the New Chronology.) If you are looking for a tidy reason why Garry has made bad decisions, I’d say it’s simply because he makes them very quickly. He doesn’t like dragging things out (what I would call contemplation) and he is very confident of the correctness of his decisions. This is essential in chess, but often a recipe for disaster in other areas, at least if you’re not as good at them as Kasparov is at chess.

This may be too prosaic, but it’s also Occam’s Razor. Since he has demonstrably improved in this area in the past five or six years (Predecessors Vol. 1 notwithstanding), I can’t imagine he was anything but worse ten or 15 years ago. It was all about action, making something happen, shocking the critics. He’s very sure of himself in just about everything and rarely seeks advice or tells people what he’s going to do.

Regarding his decline in public opinion, I think here too the answers are fairly simple. I concur with your specific examples, but the real basis is that people root for underdogs, not the favorite. When Kasparov was an outsider it was much different from when he became the status quo. Who doesn’t like a young rebel? Having power is very different from shouting at the gates. When you actually try to do something you are going to make enemies. And again he went about many of these things too much on his own, convinced he was 100% right and unwilling to compromise.’

(3689)

Concerning the introductory section of C.N. 3648, with regard to David Mabbs, see Paul Timson’s contribution in C.N. 3754.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.