Edward Winter

Arthur Ford Mackenzie

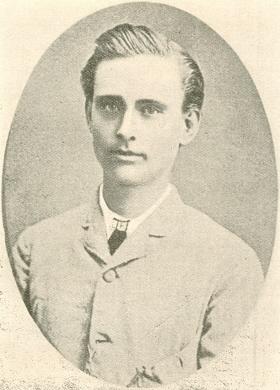

American Chess Bulletin, August 1905, page 278 (C.N.

5289)

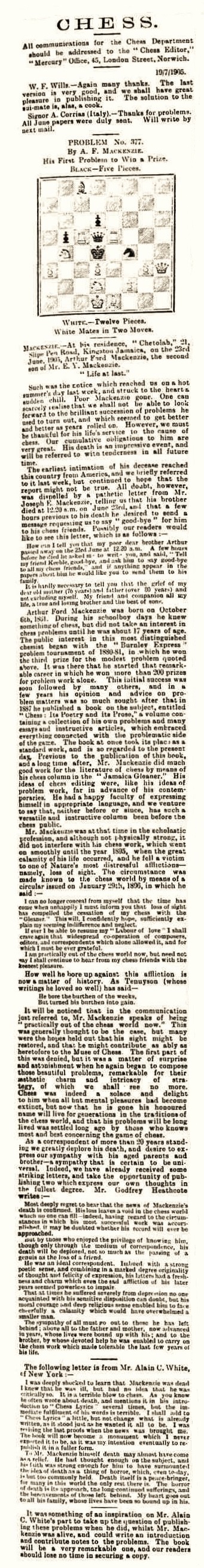

An obituary on page 217 of the 21 July 1905 issue of La Stratégie described his talent as ‘un phénomène extraordinaire’, while pages 330-331 of the August 1905 BCM stated that ‘the loss to the chess world is irreparable’ and a ‘calamitous event’, yet most chess encyclopaedias are without an entry for him. Even so, he is by no means forgotten in general chess literature and received recognition on, for instance, pages 7 and 63 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974).

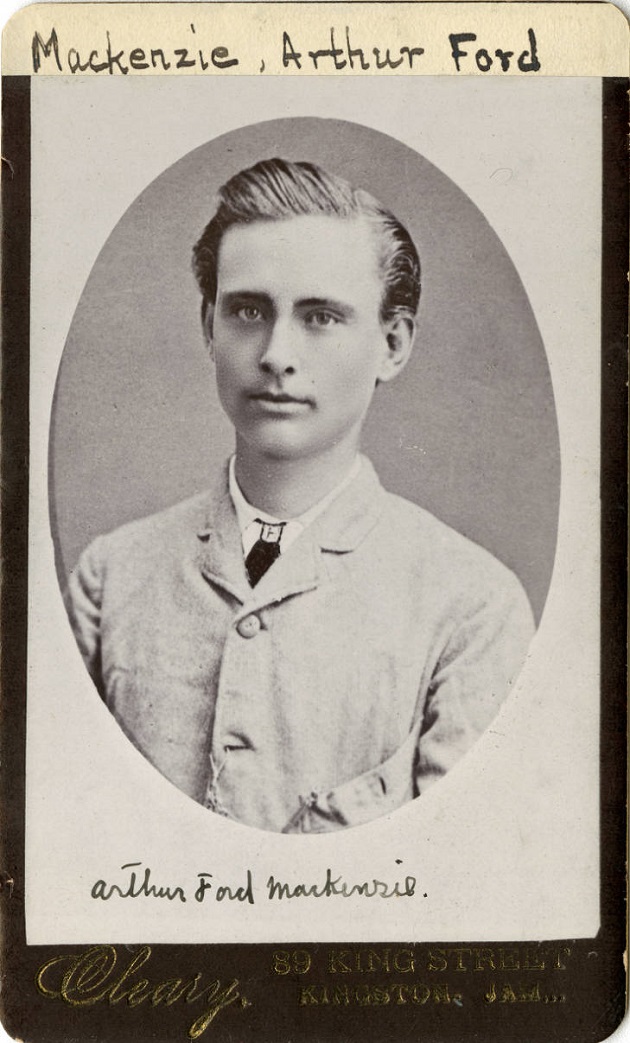

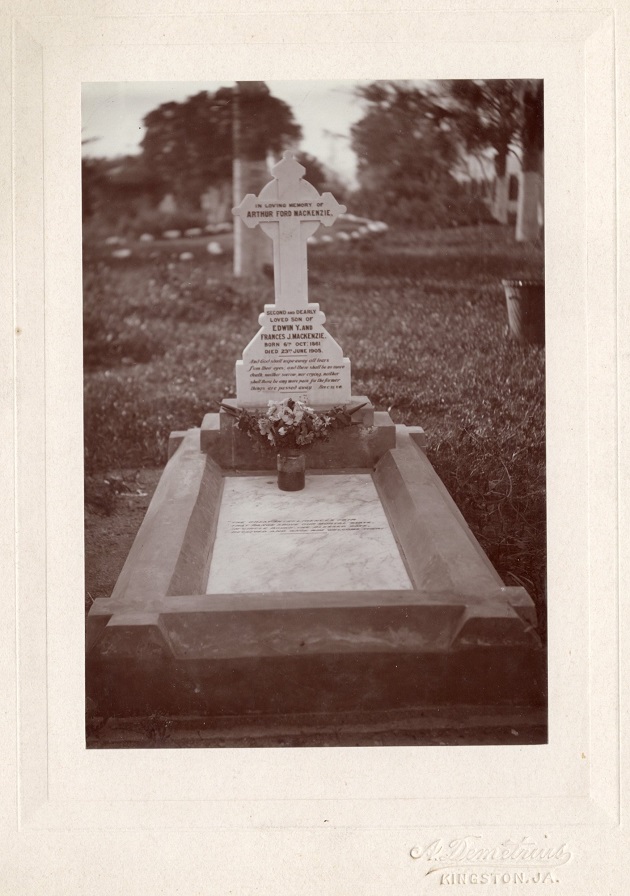

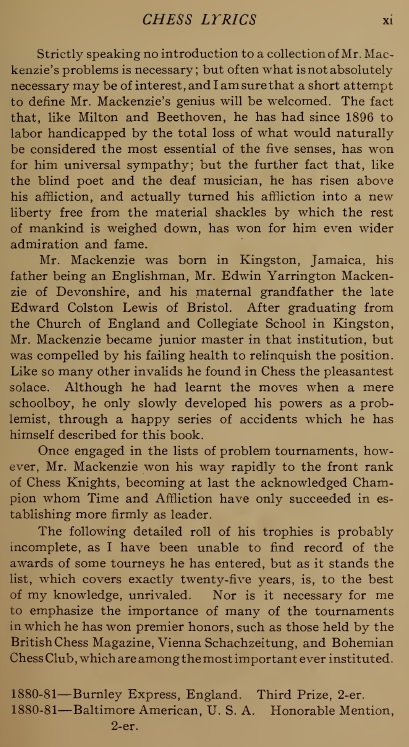

He died at the age of 43, having been blind for nearly a decade, and below we provide some brief notes on the man of whom A.C. White wrote (Lasker’s Chess Magazine, July 1905, pages 121-122), ‘as a problemist he is without a peer’ and whom page 250 of the July 1905 American Chess Bulletin called ‘the greatest composer of two and three movers combined that ever lived’. He was Arthur Ford Mackenzie (1861-1905), who was born and died in Kingston, Jamaica. A.C. White’s above-mentioned tribute noted that his death was already announced in 1896 (see page 323 of A Chess Omnibus) and that:

‘This stricken invalid, fighting year after year against blindness and ill-health, seeing, one by one, all earthly ambitions and hopes extinguished, nevertheless stands out as a noble figure, universally sympathized with, universally admired and universally mourned.’

The highest praise also appeared on pages 278-279 of the August 1905 American Chess Bulletin.

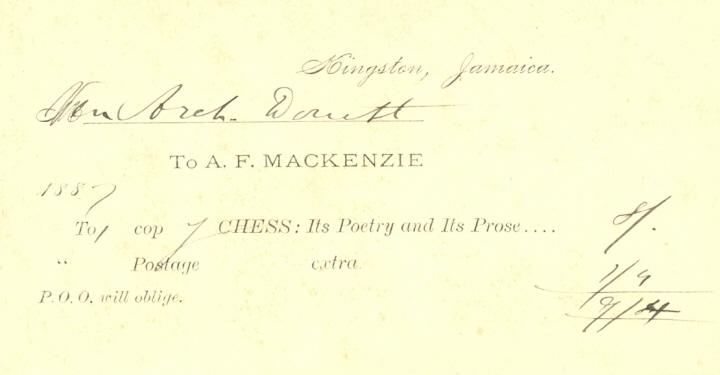

The BCM obituary mentioned that ‘when still at school Mr Mackenzie conducted a chess column in the Family Journal, of Kingston, Jamaica ...’ In 1887 he brought out in Kingston a large volume, Chess: Its Poetry and Its Prose, our copy of which has a sales slip dating from the year of publication:

The book’s title was explained by Mackenzie on page 3:

‘As practical play is the Prose, so is problem composition the Poetry of Chess, and a single problem of the modern school can be made to yield in its solution more of chess truth and beauty than an ordinary player will enjoy in a lifetime.’

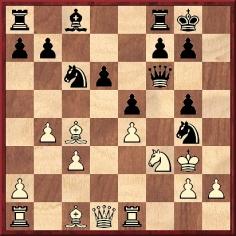

The book does not contain chess literature’s most digestible prose, but Mackenzie’s annotations to his problems were marked by critical objectivity. A separate 34-page section ‘The Elements of Chess’ dealt with over-the-board play and gave, on pages 32-33, this game:

James Leslie Main – Arthur Ford Mackenzie1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Qxd4 Nc6 4 Qd1 e5 5 Bc4 Bc5 6 Nf3 Nf6 7 Ng5 O-O 8 c3 h6 9 b4 Bxf2+ 10 Kxf2 hxg5 11 Nd2 d6 12 Re1 Ng4+ 13 Kg3 Qf6 14 Nf3

Black announced mate in three: 14...Qf4+ 15 Bxf4 exf4+ 16 Kh3 Nf2.

The volume ended with a ‘list of preliminary supporters’ (more than three pages) which included Lord Randolph Churchill, Samuel Loyd, Charles Maurian and Sir Robert Peel. Mackenzie’s posthumous book Chess Lyrics (New York, 1905) was brought out by A.C. White, and a brief supplement was published the following year.

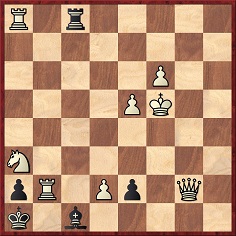

As an example of Mackenzie’s output we pick from page 301 of Chess: Its Poetry and Its Prose a problem which he contributed to the Chess Monthly, June 1884, page 317:

Mate in two

(5290)

Page 3 of Chess Lyrics by Alain C. White (New York, 1905) quoted from A.F. Mackenzie’s memoir of Steinitz in the Jamaica Gleaner, 1900:

‘One interesting trait in Steinitz’s chess character was his warm admiration for and strong advocacy of problems, the “Poetry of Chess”. He was no composer himself, but a very expert solver; and on one occasion signalized his interest in the art by taking part in a problem solution tournament. This fact is worthy of passing notice, because there are those who affect “to see no good” in problems, and depreciate their study on the hypothesis that it has a prejudicial effect on the power for play over the board. This is a most mistaken notion; for the very contrary is the fact, and the study of problems is bound to improve one’s practical play. It will be generally found, however, and it is a rather curious coincidence, that those who preach that fallacious doctrine know nothing whatever of problems. They have never journeyed through the fairyland of problem lore; nor, indeed, have they the capacity to understand or appreciate its delights. They are, in fact, so many chessical gradgrinds. With souls that cannot soar into the infinite of chess, they are dead to the spirit of its poésie. The homely aphorism “you cannot make a silken purse out of a sow’s ear” aptly fits their case; and when he who held the sceptre of the chess world for over a quarter of a century paid such high tribute to the charm and worth of problems, the apostles of that other faith may well be allowed to revel in the luxury of their own benighted belief.’

The happy term ‘chessical gradgrinds’ takes a place in our Chessy Words list. It antecedes the entry ‘… we are much mistaken if affairs chessical do not enjoy a notable enlivenment so long as he remains in our midst’ (W.E. Napier writing about Eisenberg in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, 4 August 1904).

(5347)

Page 7 of the Norwich Mercury, 1 March 1905 gave this problem by A.F. Mackenzie which won second prize ex aequo in a ‘King in Corner’ competition:

Mate in three

(11257)

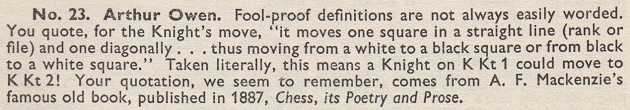

From page 136 of the May 1953 BCM, in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column:

The exact wording in A.F. Mackenzie’s book:

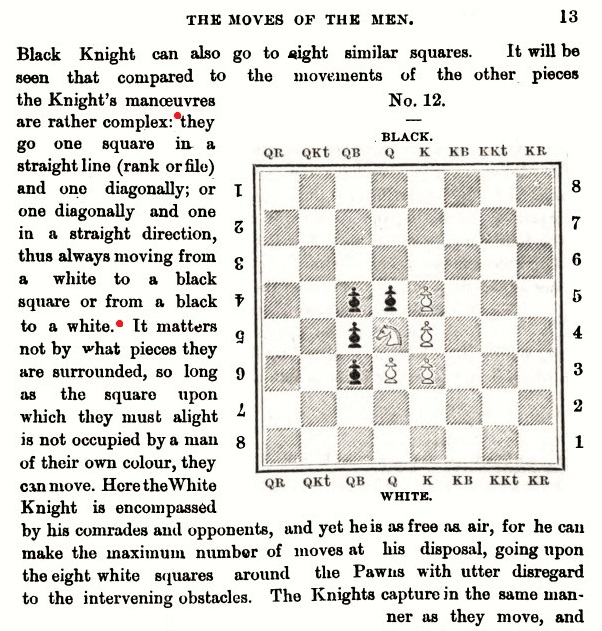

That comes from the section entitled ‘The Elements of Chess’. The full explanation of the knight’s move (pages 12-14, with three diagrams) left no ambiguity.

(11421)

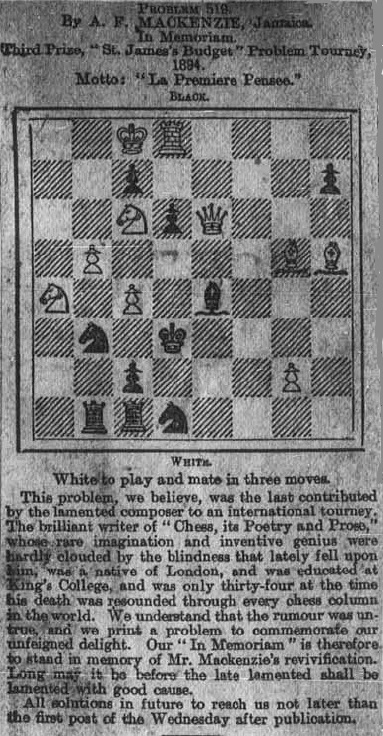

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) draws attention to this excerpt from a chess column by Robert J. Buckley in the Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 6 February 1897, as included in a set of scrapbooks held by the Cleveland Public Library:

Mr McDowell comments:

‘Buckley’s piece is strange in that it gives details of Mackenzie’s birth and education which contradict A.C. White in his collection Chess Lyrics.’

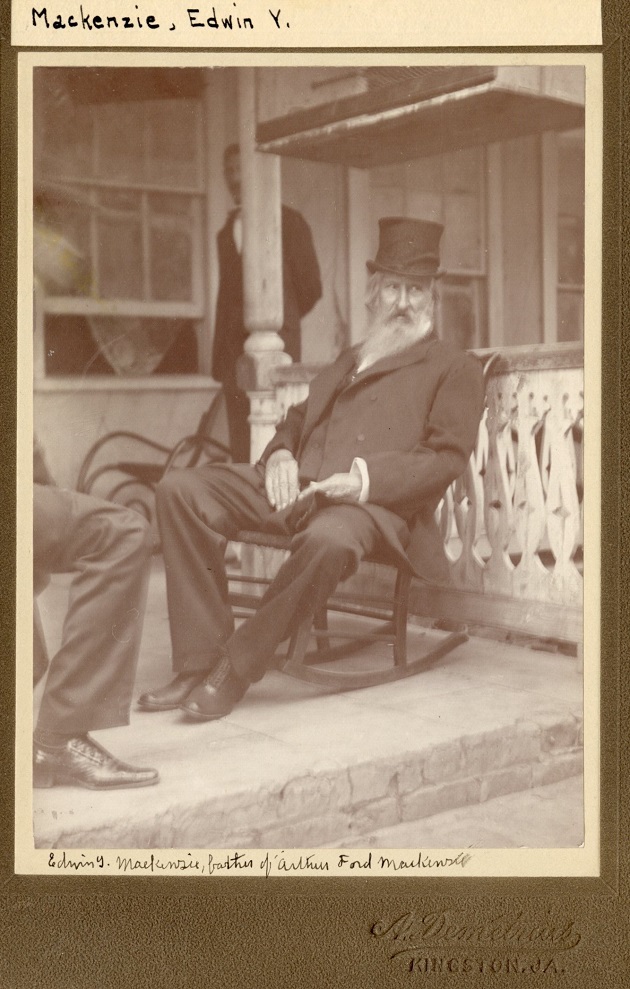

He also notes that the Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery has these photographs (reproduced here with permission):

The first of the pictures, the fine portrait of A.F. Mackenzie, is in Chess and Untimely Death Notices, from page 278 of the August 1905 American Chess Bulletin. See too C.N.s 5289 and 5290.

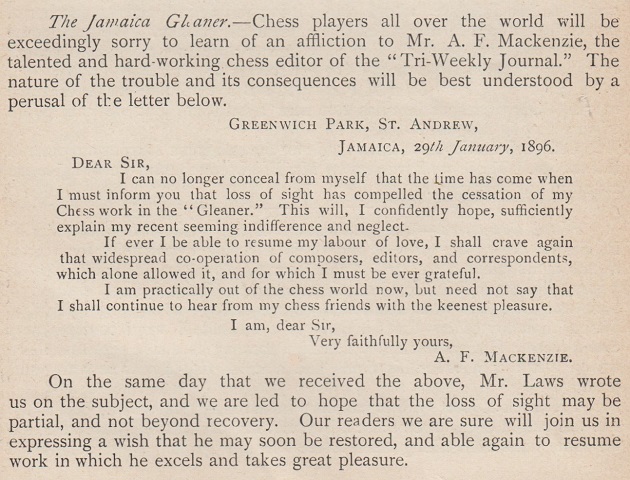

Concerning Mackenzie’s loss of sight, below is a paragraph from the Problem Department of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 24 April 1895, page 78:

‘We share the regret that is generally expressed on hearing that Mr A.F. Mackenzie, the expert in problem and general chess matters, has been suffering from an affection of the eyes, which has kept him from his favourite pursuits. We join in the wish that he may be speedily restored to health.’

A letter from Mackenzie was published on page 135 of the March 1896 BCM, in the ‘Problem World’ column conducted by James Rayner:

Rayner and Mackenzie died in, respectively, 1898 (aged 38) and 1905 (aged 43).

We conclude with John Keeble’s column in the Norwich Mercury, 19 July 1905, page 7:

(11736)

Information about A.F. Mackenzie’s origins is supplied by Michael McDowell, from page xi of the collection of Mackenzie’s problems, Chess Lyrics edited by Alain C. White (New York, 1905):

(11744)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.