Edward Winter

(2002, with updates)

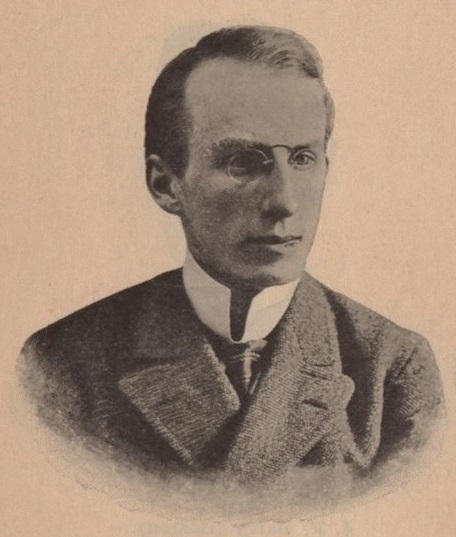

William Ewart Napier (See C.N. 12030 below.)

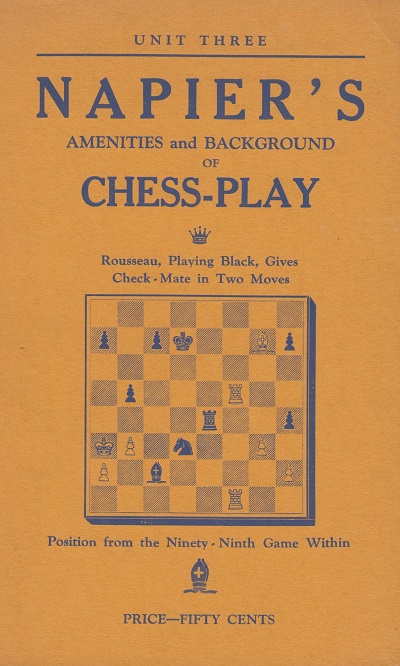

Although W.E. Napier (1881-1952) was a highly quotable writer, he produced only one chess work, Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). After his death they were adapted into a single volume entitled Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957 and 1971).

In the quotations below (some of which have entered chess lore) the figures refer to the item numbers in the Amenities work, the pages of which were unnumbered:

I saw him once at Simpson’s Divan but not to speak to. I brought away an impression of fulminating chess, of hearty laughter and liberty and beefsteak. He romped.

Once I asked Teichmann what he thought of Bird’s chess; “Same as his health”, he replied, – “always alternating between being dangerously ill and dangerously well.”

England will not know his like again.’

He is very unusual.’

The paradox is baffling.

The only theory I have adduced is that the social nature of mail exchanges quite subordinates mere winning to joyful, yawing chess.

In match games over the board, the killing instinct necessary to success is the same that men take into Bengal jungles, – for a day. A killing instinct which survives the day and endures month in and month out, is stark pantomime; and mail chess is the gainer by it.’

Said the enemy, “I’m not cut.”

And the knight of the razor replied, “Just wait till you turn yo’ head, before guessing at it.”’

Note: The entirety of the above compilation has been copy-pasted, without acknowledgement, on a chessgames.com page.

‘What he was in the ’80s and ’90s he [Tarrasch] is now and seemingly ever will be, one of the best. Only this and nothing more. He is a vastly learned chess master, which quality, coupled with stamina worthy of a Marathon runner, renders him superior to everything but the pelting of downright genius.’

Napier in the Pittsburg Dispatch, quoted on page 127 of the July 1907 American Chess Bulletin. The passage was given on page 387 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

Quoted on page 388 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘The great players also lose in short order. We hear very often from a modest player of small proficiency that he shirks taking on players of renown because they would “wind him up” in a trice; and, per contra, we often hear it boasted by the same sort that he was the last to capitulate in a simultaneous performance. Yet the length of the game is relatively unimportant. It is no praise to have won in 15 moves nor any disparagement to lose as speedily.

Great chessplayers are only comparatively great; and they all have weak moments, and occasionally whole seasons of disability, when their best moves are not better than their worst at other times. Duration is no reliable criterion of a game’s quality; indeed, there is a certain wooden style of play which is quite devoid of spirit, but is for all that tenacious and hangs on to insufferable length. Let the tyro take heart, and not proclaim himself a duffer for the brief compass of his games.’

W.E. Napier in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, quoted on page 16 of the January 1907 BCM.

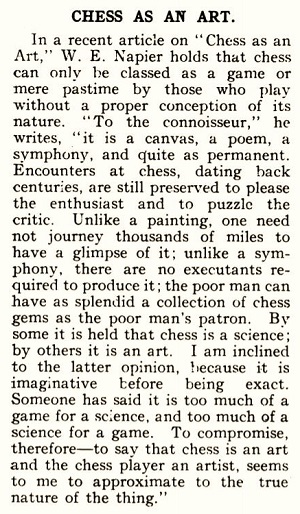

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) asks for the origin of a remark attributed to W.E. Napier on page 260 of 777 “Chess Miniatures in Three” by E. Wallis (Scarborough, 1908):

‘A good problem – to the connoisseur is a canvas, a poem, a symphony, and quite as permanent.’

(5829)

We note that when the passage was attributed to Napier on page 72 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, June 1905, there was no reference to chess problems:

A brief item on page 151 of the May 1952 CHESS:

‘W.E. Napier won the British Championship in 1904 then emigrated to the USA and for some years challenged Marshall and Pillsbury. His three slim volumes of Chess Amenities (selected games annotated with a delightfully light touch) are much-sought literary gems. He is suffering from advanced cancer of the throat but has written a new book Evergreen Chess.’

Napier died a few months later. The manuscript of Evergreen Chess had been conveyed to Hermann Helms but has never been traced, let alone published. Further information is available on pages 352-354 of Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 1997).

(6843)

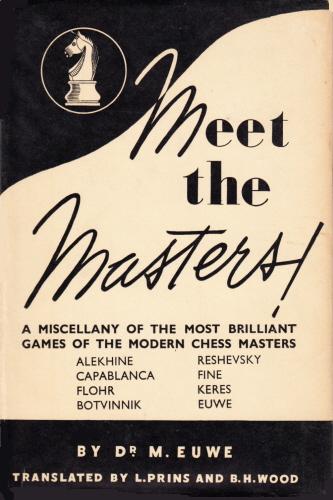

‘He was described as “a man-eating tiger”’, commented page 34 of the February 1982 BCM at the start of ‘Dr Max Euwe (1901-1981) In Memoriam’, without any details being furnished. On page 73 of Max Euwe (Alkmaar, 2001) Alexander Münninghoff provided a ‘once’ version:

‘“An efficient man-eating tiger” was the epithet the American master Napier once coined for Euwe ...’

The phrase had been quoted by Lodewijk Prins on page 166 of Master Chess (London, 1950):

‘Euwe has been described by W.E. Napier as “an efficient, man-eating tiger”. The phrase sounds far-fetched, and many who regard the former world champion as primarily a positional player and theoretician will be surprised at this qualification. The following game from the Dutch championship, 1938 [a draw between van Scheltinga and Euwe] may make them change their minds.’

In item 147 in ‘unit two’ of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (New York, 1934) W.E. Napier wrote:

‘Euwe v Alekhine

As contender for the proud title held by Alekhine, any game between them has special interest.

This one, played in Amsterdam, in 1926, exhibits a challenger of steady nerve, stout heart, and an efficiency like a man-eating tiger’s, – working at his trade.’

Napier then gave the eighth match-game between Euwe and Alekhine (The Hague, 1927, in fact), chopping off the last ten moves by putting ‘32 P-R6 Resigns’.

When the game, still shortened and still misdated, appeared on pages 251-252 of the single-volume edition of Napier’s book, Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957 and 1971), the introductory text was also curtailed, maladroitly:

‘This game, showing Euwe when he was a contender for Alekhine’s crown [sic – the match took place almost a year before Alekhine became world champion], exhibits a challenger of steady nerve, stout heart, and an efficiency like a man-eating tiger working at his trade.’

(8326)

‘The American grandmaster Reuben Fine called Euwe an efficient man-eating tiger.’

That comes from page 89 of My Chess (Milford, 2013), Hans Ree’s latest collection of superior nattering, but it is unclear why Fine’s name has been introduced. As regards the attribution to Napier (C.N. 8326), the following appeared on page 11 of Euwe’s Meet the Masters (London, 1940):

‘Napier once described Euwe as “an efficient man-eating tiger”.’

Page v of the Preface implies that this section was written by L. Prins and B.H. Wood.

...

(8335)

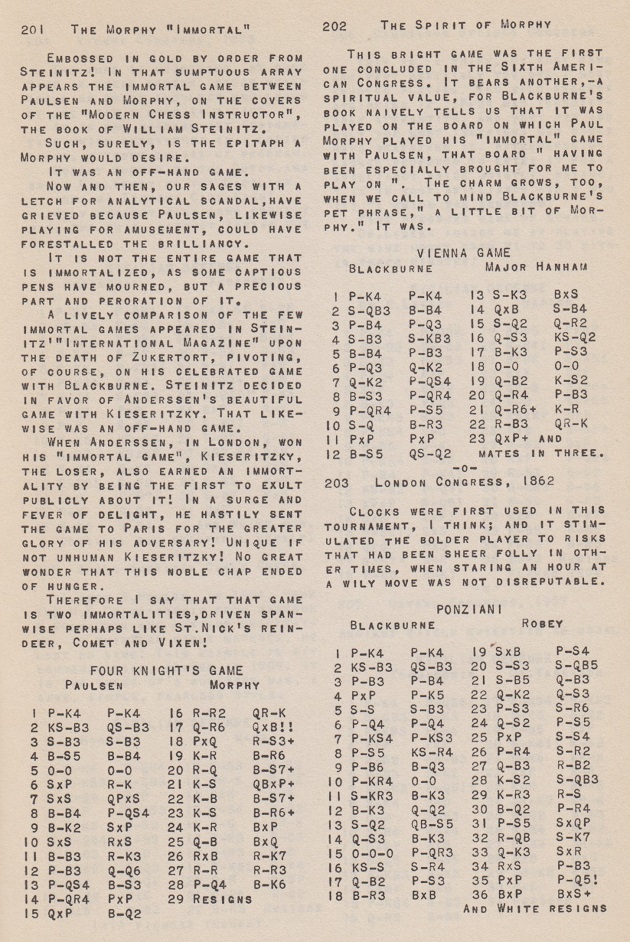

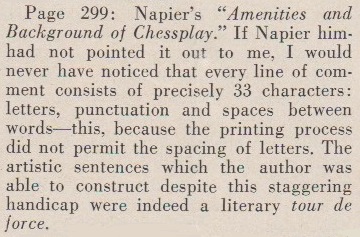

What is the peculiarity of the text below?

That page, picked at random, is the first of unit three of Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (New York, 1935).

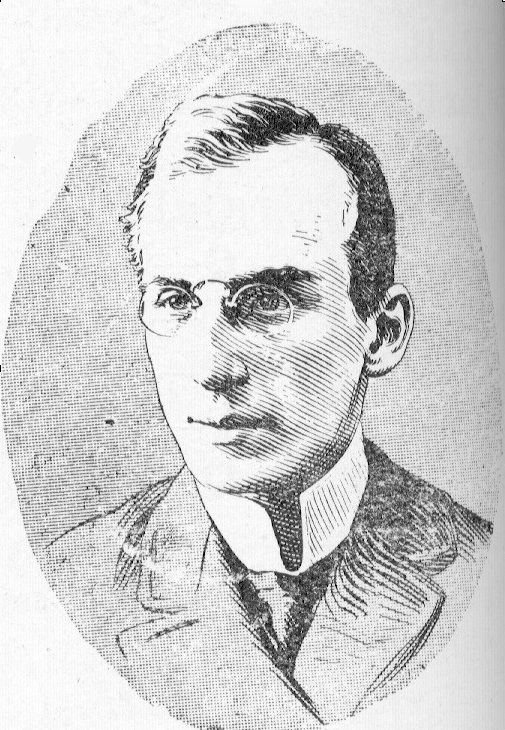

William Ewart Napier (Wiener Schachzeitung, August-September 1904, page 260)

The textual peculiarity was mentioned by K.O. Mott-Smith in a letter on page 353 of the December 1952 Chess Review:

(10689)

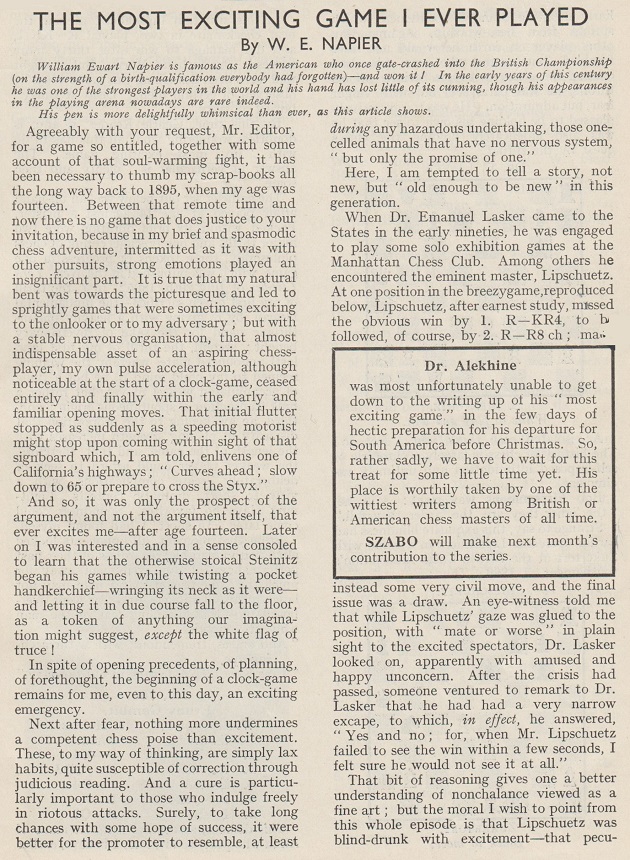

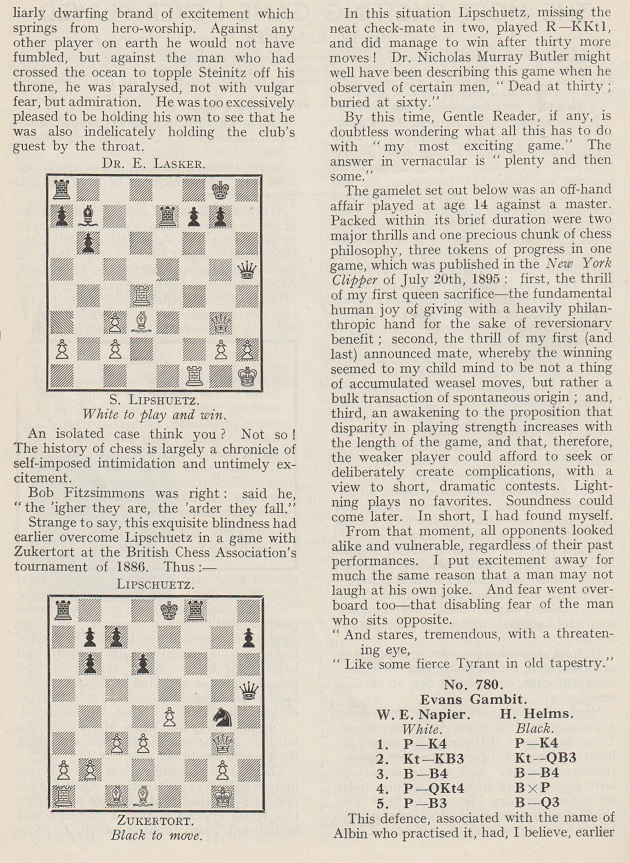

From pages 179-181 of CHESS, February 1939:

In the first diagram a black pawn is missing from c5. The remark by Napier in the ensuing paragraph is notable:

‘The history of chess is largely a chronicle of self-imposed intimidation and untimely excitement.’

It is also worth highlighting the CHESS Editor’s comment about Napier in the box on page 179: ‘one of the wittiest writers among British or American chess masters of all time.’

Napier’s article and the game against Helms were discussed on pages 13 and 339-341 of Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 1997). Helms wrote tributes to Napier on pages 86-87 of the September-October 1952 American Chess Bulletin and on page 70 of CHESS, Christmas 1952/January 1953.

(10690)

The first paragraph of ‘Chess Lore’, an article by W.E. Napier on pages 98-99 of Checkmate, February 1903:

‘The best book on chess? The question blossoms afresh with every new student of the game, and the answer, if candid, is ever the same: “Gather all you can from every good source, and let experience prove the worth or worthlessness of your harvest.” As in other things, mere bookishness is not knowledge, nor on the other hand is a fine disregard of chess literature a key to proficiency; and the beginner drinking in the plausible hallucinations of a Gossip or a Staunton is quite as misguided as he who heeds the warning of a Lasker to give the chess book a wide berth.’

(10699)

From page 118 of the February 1905 issue of The Rice Gambit, Souvenir Supplement to the American Chess Bulletin:

This photograph was published on page 129 of the August 1897 American Chess Magazine:

Larger version and detail of the front row

We see no caption in the American Chess Magazine, but as mentioned on page 408 of the first of two volumes on Pillsbury by Nick Pope (see the end of our article Harry Nelson Pillsbury), those seated nearest to the camera are Borsodi, Hanham, Pillsbury, Lipschütz, Pieczonka, Steinitz and Napier.

An Albert Pieczonka webpage shows another photograph from the same location.

Page 148 of the August 1897 American Chess Magazine has the group portrait given in C.N. 5550, and the following is on page 149:

The above images have been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

(12030)

See too The Best Chess Games.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.