Edward Winter

From Fred Wilson (New York, NY, USA):

‘According to Elo, in his book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present, Alekhine is only tied for 6th-7th place with Smyslov, on the “best 5-year average rating list” with his best being 2690 (presumably his best 5 years being – I hope – 1927-31). According to Elo, Fischer, Botvinnik, Karpov, Lasker and Capablanca all had higher “best 5-year averages” and therefore were better (stronger?) players. I simply do not believe this, but then I also insist on judging (subjectively, I know) the quality of the games played: I wonder if any of our “math-minded” fellow enthusiasts have any comment on Elo’s relatively low ranking of Alekhine, and can perhaps even refute Elo with his own weapons.’

(558)

Some reflections from W.D. Rubinstein (Victoria, Australia):

‘I agree with Fred Wilson that Alekhine’s peak of “only” 2690 Elo rating is very odd. My guess is that it can be expressed this way: in the period 1927-31, Alekhine played 182 games at master level. Of this number, 69 were in matches. Although Alekhine’s tournament performance, especially after 1927, was obviously at a 2700+ level, his match record was much more mixed. In particular, his two matches of 1927 against Capablanca (+6 –3 =25) and Euwe (+3 –2 =5) detracted from his overall level – these accounted for 24.2% of his total master-level games. Capablanca, of course, had a rating of 2720 or so at his peak (1918-22) but from 1927 (or earlier) declined fairly quickly until the mid-1930s. Capablanca’s rating for the 1927-31 period was probably no higher than, say, 2660-2670. Alekhine scored 54% against Capablanca, arguing that his (Alekhine’s) rating for this match was 2675-2680 or so. Alekhine’s performance against Euwe, who was barely at the 2600 level, if that, in 1927, was even worse. Alekhine’s performance in his 1929 match against Bogoljubow (+11 –5 =9) was roughly consistent with their standing at the time, but Capablanca’s lifetime record against Bogoljubow was +5 –0 =2. Alekhine’s match record in this period was thus, it would seem, consistent with a rating of, say, 2675 or so. If Alekhine’s superb tournament record is taken into account, this will still raise his rating only to about 2690. This still sounds low, but it is probably Alekhine’s match record which accounts for this. It should not be forgotten that Alekhine’s overall record in 1927-31 was +88 –15 =79 (70.1%), which is not as overwhelming as Lasker, Capablanca or Fischer at their peaks.

The second reason why Alekhine’s rating may be low is that his record prior to 1927, while excellent, was not the towering achievement it became between 1927 and 1934. There was, of course, considerable doubt before 1927 as to whether he was the second best player in the world – Lasker, Nimzowitsch, Bogoljubow and possibly Rubinstein and Spielmann all had claims on this position between 1922 and 1927. Since Elo ratings take account of one’s previous record for a considerable time afterwards, Alekhine’s dramatic improvement from 1927 was still pulled down in his rating by his previous record.’

(651)

Following on from the preceding item, Dr Rubinstein asks whether anyone has ever compiled one-, three- or five-year rating lists for the pre-1970 period. He adds:

‘Elo’s tables and charts must be based on such lists; but have they ever been published?, Who, for example, were the ten strongest players in the world in 1925, and what were their ratings?’

(652)

From Ken Whyld (Caistor, England):

‘Retrospective ratings were done extensively by Clarke and Elo, who shared their findings. Clarke published an important listing, but only back to 1946, in the BCM 1960, pages 326-328. In 1973 he had three articles in the BCM, pages 103-111, 147-151, 178-180. This gives the information requested by Dr Rubinstein. Sir Richard Clarke shared his findings with me (we were old friends). I used them to make retrospective categories for all tournaments, and one result was my article in the January 1978 BCM giving the categories of the top 100 tournaments in the first century of tournament chess. Another use for these categories was to calculate all GM norms, by present-day criteria, and this has been an essential factor in the selection made by Hooper and me of players to be included in the Oxford Companion. The BCM for 1973 page 150 lists the following for 1925-29: Alekhine 2705, Capa 2685, Nimzowitsch 2640, Bogoljubow and Vidmar 2620, Euwe and Rubinstein 2600. I can add, from Clarke’s papers, which were transferred to the BCF about five years ago, the next few names: Tartakower 2560, Spielmann and Torre 2550, Marshall and Maróczy 2540, Romanovsky, Levenfish and Réti 2535, Atkins and Grünfeld 2530, Verlinsky 2525, Rabinovich 2510, Canal 2505.’

We are invariably torn two ways over retrograding; it is undoubtedly a fascinating subject but ... From 1925 to 1929 did Marshall and Maróczy really perform no better than K. Spraggett in 1983? Are the old-timers receiving justice?

(710)

Page 195 of Arpad E. Elo’s The Rating of Chessplayers Past & Present (London, 1978) lists Edward S. Tinsley 1869-1937 and gives him a best five-year average rating of 2400. We cannot believe this and feel there must be a mix-up by Elo over the father and son.

(719)

From Rene Olthof (Rosmalen, the Netherlands):

‘It is perfectly possible that Kevin Spraggett is of equal strength compared to a Marshall or Maróczy. What could they do that Spraggett cannot? In my view, contemporary players are constantly being underestimated or, rather, old-timers are being overestimated ... it always used to be better in the old days. They were even better dressed then ... But does anyone realize the chess scene in general has improved enormously in recent times? Think about Schlechter literally starving to death. Mason is another example of what used to happen.’

(We would prefer to keep separate the questions of playing strength and remuneration. As a partial answer to our correspondent’s first question; against the world champion Capablanca at Lake Hopatcong, 1926 Maróczy scored a draw and a loss, and Marshall two draws. We find it senseless to believe that Kevin Spraggett would be remotely capable of such an achievement.)

(766)

W.D. Rubinstein writes:

‘Your comment “are the old-timers receiving justice?” from retrograding (which shows Marshall and Maróczy 1925-29 equal with today’s K. Spraggett) is an interesting point. I think most chess historians intuitively feel that yesterday’s legendary heroes are better than today’s players, perhaps because they have famous names. For instance, in an interesting article on “Lasker and the Devil” in Lasker and His Contemporaries No. 3 (1980), the excellent Canadian researcher Dr Nathan Divinsky used Elo’s peak ratings to make an all-time league table. However, finding that Nimzowitsch and Averbakh were equal at 2615, while Chigorin, Zukertort and Taimanov all peaked at 2600, Divinsky stated that the Elo system “has a tendency to inflate the ratings of current post-1940 players” – and knocked 30 points off all post-1940 peaks “to fit my own intuitive measure of the relationship between the old and new”. His feelings would be widely shared, unquestionably. But I would suggest that this perspective might be turned on its head. One of the strangest things about chess in the contemporary world is that although it is more popular than ever, really first-class players are no more frequent than in the distant past. In the Soviet Union, for instance, chess ability is systematically identified and trained from every nook and cranny of that country’s 270 million people, and chess masters receive considerable privileges and prestige. Yet despite this, there is not a single player in the Soviet Union (or anywhere else) at the present time with a current rating as high as Lasker or Capablanca at their peaks, and only two players currently as good as Paul Morphy was in 1860. Just by the law of averages, one might expect there to be 20 Capablancas around today, but there aren’t. This strikes me as being a lot stranger than any “inflation” in the recent Elo ratings. Possibly the fact that there are more very good but not great players today diminishes the very peaks; or possibly it is simply sheer coincidence – extreme talent appears in an unpredictable manner and it just hasn’t appeared very frequently lately. Another possibility is that there are generational “waves” of chess talent, with three notable such waves this century: c 1907-14 (when Capablanca, Alekhine, Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch, Bogoljubow and Spielmann first came on the scene), c 1931-40 (Botvinnik, Kashdan, Reshevsky, Fine, Flohr, Keres, Najdorf, Smyslov) and c 1951-60 (Petrosian, Korchnoi, Geller, Larsen, Spassky, Fischer, Tal). There “should” have been another such wave in the 1970s, but the 1970s wave (Karpov, Hübner, Miles, Timman, Ljubojević, Ribli, Andersson, Kasparov, etc.) is much weaker than those of the past.’

(767)

From C.D. Robinson (Toronto, Canada):

‘As for ratings, there is no objective or statistical basis for extending ratings into the past: Professor Elo’s suggestions are merely opinions expressed in numbers instead of words.’

(792)

A contribution from Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA):

‘Modern masters are over-estimated in my opinion – but Spraggett could have drawn with Capablanca on occasion (not the best choice of example considering his 1984 triumphs in New York and Hong Kong!)’

(831)

Dr Rubinstein writes:

‘C.D. Robinson’s contention that “there is no objective or statistical basis for extending ratings into the past” is flatly wrong and surely based on ignorance of Elo’s major work The Rating of Chess Players Past and Present, where the mathematical basis of the Elo rating system is explained, as well as the massive research Elo and others have put into rating past players from hundreds of tournaments and matches back to 1851. There is absolutely nothing subjective about the Elo ratings of past players and they do not involve any “opinions”, as anyone who has read Elo’s work can see.’

From Ken Whyld:

‘C.N. 792 puzzled me. Although I would not share it, I could respect an opinion that all rating is bunk, but what Robinson says makes no sense. Perhaps he does not know that Elo and Clarke built up their different bases by making gradings from the mid-nineteenth century. The first figures were purely subjective but by statistical reiteration they became refined and were then used to generate the ratings for later players. All present ratings derive ultimately from unpublished ratings made of past ages. If Robinson is trying to say that rating does not reveal the “box-office attraction” of a player, then I would agree. Mieses is a good example of one whose occasional flashes endear him to the public despite an overall indifferent record.’

(853)

Issue 35 of the Myers Openings Bulletin once again shows its Editor in cracking form, notably in a set-piece article on ratings which presents powerful arguments to suggest that the current practices are far from fair or accurate. For the record, W.D. Rubinstein’s view in C.N. 853 is referred to in the article.

Hugh Myers seems to have a winning formula with recent MOBs: analysis/reflective editorial/book reviews.

(940)

Page 91 of Elo’s The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present mentions a 14-game Capablanca-Kostić match (1915). No such match was ever played, and it would seem that Elo was misled by the false information in Dr P. Feenstra Kuiper’s Hundert Jahre Schachzweikämpfe (pages 76 and 84). If Elo’s historical data are largely based on Feenstra Kuiper many of his oft-quoted retrogradings will be way out.

(1302)

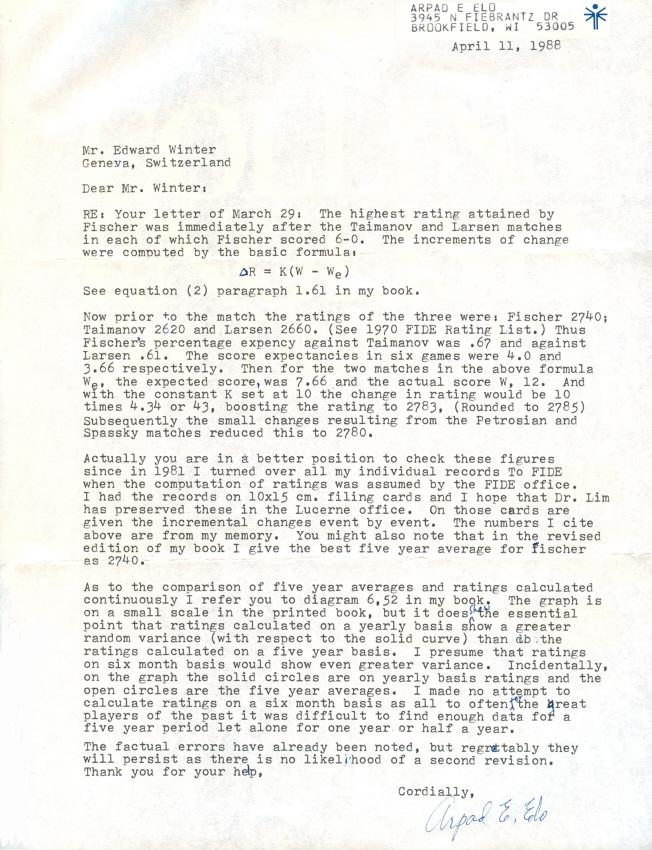

We should still welcome clarification of the points regarding retrograding made in C.N. 1302. Three other questions. Can anyone explain exactly how Fischer’s extremely high Elo rating was calculated? To what extent can six-monthly ratings be justly compared to best five-year periods? Has anyone attempted to calculate the ratings of the great players of the past on a six-monthly basis?

(1601)

(1604)

... Elo’s retrospective rankings look less and less convincing the more one studies them. For example, George Walker is attributed 2360, the same as George Botterill in January 1988 (who has thus had the benefit of insight into a century and a half of chess development since Walker’s time).

(1638)

From Ken Whyld:

‘The final paragraph of C.N. 1638 shows a misunderstanding of Elo. The ratings do not reflect how a player from a past age would fare against a present-day player. In his day George Walker might well have been of the same standing as Botterill is today. If Morphy were alive today and played exactly as he did in 1858 then he would be well down the list. Of course, with his great ability he would quickly absorb most of contemporary theory and begin to climb. His historical rating shows his place in his time.

Elo’s figures measure competitive ability, not the quality of play. To misquote Grantland Rice, “It matters not how well you play the game, but whether you win or lose”. It is easier to visualize if we consider how Elo might have been applied to athletic events, where there are absolute measures of performance. An Olympic gold medallist might be, say, 2600, whether winning the medal now, or 50 years ago. But the performance 50 years ago would probably not even be a qualifying result for today’s event. It does not follow that athletes of half a century ago would not be able to sustain their hypothetical “Elo” if they were miraculously to reappear without having aged at all, but they would have to make better times, etc. to do it.

In chess we can only know the standing of players within the pool of which they are a part. It is idle speculation to make comparisons between discrete periods. Just as thousands of marathon runners beat the time which won the first Olympic medal, so thousands of chessplayers could, with the knowledge and skill they have, repeat Morphy’s performance if they were transported back in time. But if these same players had been contemporaries of Morphy then they would likely have been outclassed by him, just like everybody else.

There must be about 50 games by Walker available, quite enough to form a reasonable Elo. You are certainly right to question the completeness and accuracy of Elo’s sources. Before Gaige’s unfinished project such records were patchy, to say the least, and when he has completed his record of crosstables we can expect a great improvement in retrograding. Matches are quite inadequately covered in Feenstra Kuiper’s book. Graders do not need all results so as to be reasonably accurate, as long as the missing data are in line with the rest. If the omitted result is untypical the effect could be important. Had Kostić “beaten” Capa in the fictitious match its inclusion could have been serious.’

(1697)

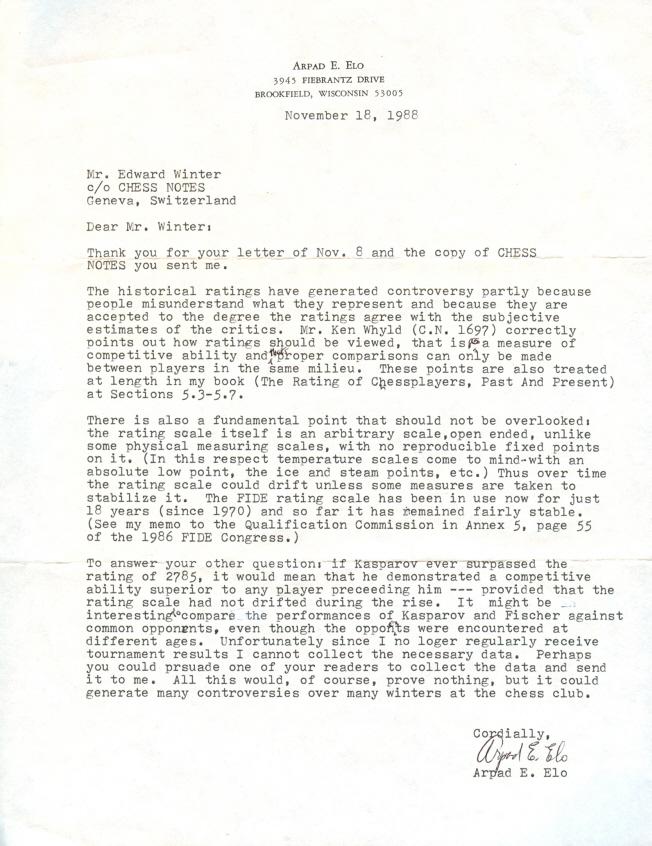

Professor A. Elo comments on C.N. 1697 and also answers a question from us as to whether Kasparov, if he surpassed 2785, would have proven himself ‘the strongest player of all time’. Although it has been established that different periods cannot be directly compared, is Fischer’s career sufficiently recent to allow comparisons with Kasparov?

(1773)

From Hugh Myers:

‘The Elo rating system is so fundamentally inaccurate that it would be ridiculous to grant or remove GM titles based on ratings of 2450 or 2449. Elo wrote on page 18 of issue 36 of the Myers Openings Bulletin:

‘The term accuracy is not even properly applicable to ratings.’

[See the section entitled ‘Inflation and proposals to reform terminology”’ in Chess Grandmasters.]

(1807)

From Svend E. Henriksen (Nyborg, Denmark), who is researching retrograding and developing a system which allows odds games to be included in calculations:

‘With regard to C.N. s 1638 and 1697, I should 1ike to make the following comment: K. Whyld says that retrogradings are reasonably accurate “as long as the missing data are in line with the rest”. A careful inspection of the games of G. Walker given in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games and Walker’s own Chess Studies (the two sources available to me) shows clearly that his matches against such players as Slous, Perigal and Popert must almost certainly be not only incomplete (as recorded by these two sources) but also more or less strongly weighted in favour of G. Walker. I hasten to add that this weighting was surely not intentional on Walker’s part – we know him to have been a gentleman – but must have had its unintentional origin in the fact that he (or some other editor) in his search for suitable examples of games to present to readers of his books, magazines and columns subconsciously left out those games in which he himself had made a less strong and hence perhaps less instructive showing. Thus, in using the old games material, the analyst must, for each match played, be on his guard for, among other things, a possible bias-producing incompleteness.

I do not agree with Ken Whyld’s statement: “In chess we can only know the standing of players within the pool of which they are a part. It is idle speculation to make comparisons between discrete periods.”

On the contrary, it is possible for a careful and unbiased analyst to make absolute comparisons of the chessplaying ability of players across the ages, albeit of a lesser accuracy than those obtainable from material in the modern period of frequent chess events, careful and complete recording and orderly arrangement of the events.

The calculation of relative Elo ratings of a group of players within a pool of an extent of half a year (or, for older times, one, two, three or four years) is made by the method given by Arpad E. Elo and outlined in his book, supplemented (in the case of older material) by the suggestions that I have been developing. (I have also, in a letter to Professor Elo, given a calculation short-cut which reduces the number of iterations in the iterative calculation of a pool.) All this is straightforward, and the only thing required before the calculator reaches the final values is an adjustment of the whole group of players from the time interval (the pool) up or down by a definite amount (number of Elo points).

We have two means available, both of which could or should be used, for making this group-moving adjustment. 1) a careful application of Elo’s “average performance as a function of age of player” will help placing the group at a proper level, and 2) my “error-index” method, which is based on a comparison with, or with an eye to, the contemporary development of opening theory and also contains checks against bias in judgement.’

(1880)

Wanted: early attempts to rank leading masters. One was made by Edward Lasker on page xii of his book Chess and Checkers, the Way to Mastership (New York, 1918). He proposed: 1st Em. Lasker; 2nd Capablanca; 3rd Rubinstein; 4th Schlechter; 5th Marshall; 6th Teichmann; 7th Alekhine.

(1976)

The view of W.H. Cozens, given on page 161 of the April 1976 BCM:

‘The obsession with grading is fast becoming the curse of chess; from the top (where the multiplication of grandmasters already calls for the creation of a new supermaster class – the dozen or so with legitimate pretensions to a world title match) right down to club level where it is simply laughable.’

(2010)

We have received the following from Louis Blair (Carlinville, IL, USA):

‘John D. Beasley made some striking remarks about Elo and ratings (referred to by Beasley as “grades”) in his book The Mathematics of Games (Oxford, 1990):

“... certain practical matters must be decided by the grading administrator, and these may have a perceptible effect on the figures. ... Grades are therefore not quite the objective measures that their more uncritical admirers like to maintain.” (Page 54)

“Students of all games like to imagine how players of different periods would have compared with each other, and long-term grading has been hailed as providing an answer. This is wishful thinking. … it is natural to speculate how [Morphy and Fischer] would have fared against each other; but such speculations are not answered by calculating grades through chains of intermediaries spanning over a hundred years.” (Page 61)

“Elo’s work as described in his book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present (Batsford, 1978) is open to serious criticism. His statistical testing is unsatisfactory to the point of being meaningless; ... his ‘deflation control’, which claims to stabilize the implied reference level, is a delusion.” (Page 61)

“Elo deserves the credit for being a pioneer and for doing a great deal of work, much of it before automatic computers were available to perform the arithmetic, but his work contains too many errors to be acceptable as a continuing standard.” (Page 163)’

(3223)

An extract from William Hartston’s chess column in Now!, 1-7 August 1980, page 82.

‘I met the eponymous professor [Arpad E. Elo] during the chess olympics at Nice in 1974. He was besieged with requests by players wanting the rules bent to accommodate their own requests for international titles. When the last of the supplicants had gone, Professor Elo said to me: “I think I have created a monster.” I think so too.’

(6742)

A question from Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA): what are the best sources of information about Elo ratings, including such matters as whether a given master ever reached the top ten?

We have many, but not all, of the booklets International Rating List brought out twice yearly by FIDE. To mention just the edition of exactly 20 years ago, the 203-page tome was sponsored by IBM and published by the FIDE General Secretariat in Athens:

Have bibliographical details for the full run ever been prepared?

Also sought are the best (most accurate and comprehensive) on-line resources. The OlimpBase website has a ‘History of Elo ratings 1971-2001’ which allows searches for individual players, as does FIDE’s Ratings page.

(8701)

In the ‘Rating Systems’ entry on pages 271-272 of Harry Golombek’s The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977) William Hartston wrote:

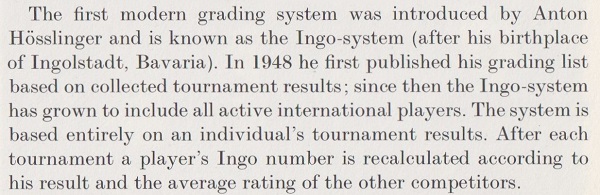

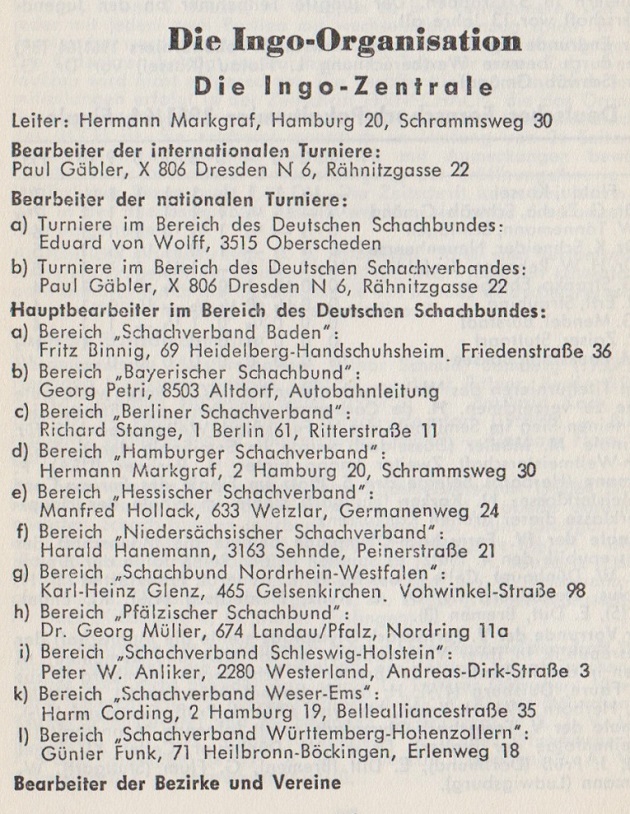

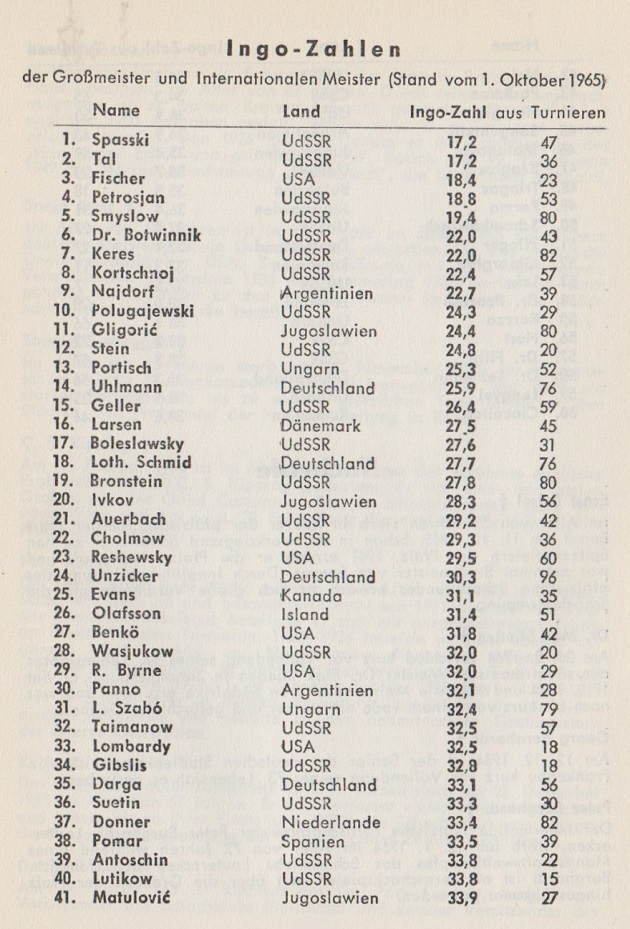

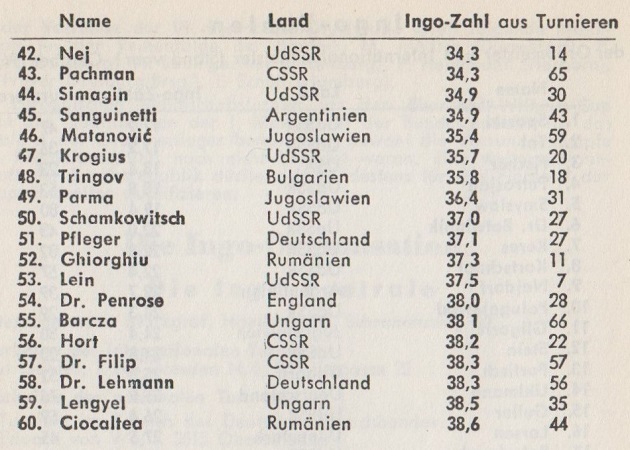

Although the Ingo system is mentioned in many chess reference books, and especially German ones, it is nowadays all but forgotten.

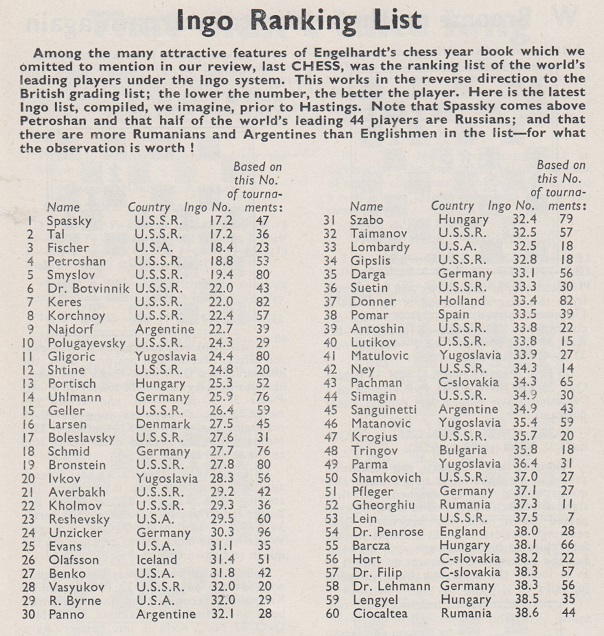

From page 255 of CHESS, Easter 1966:

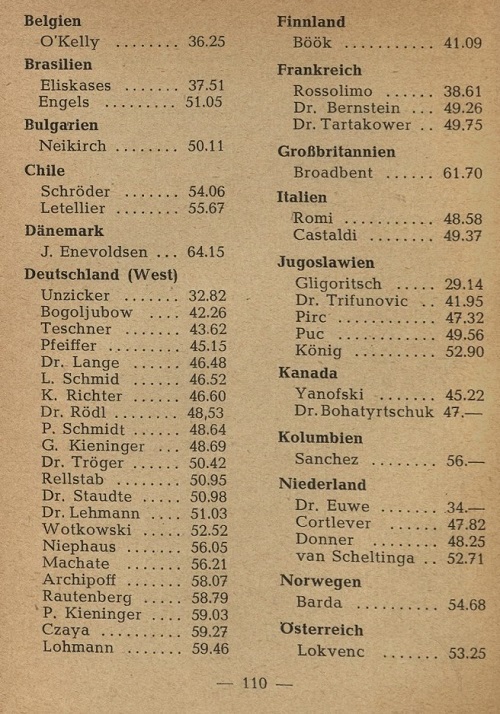

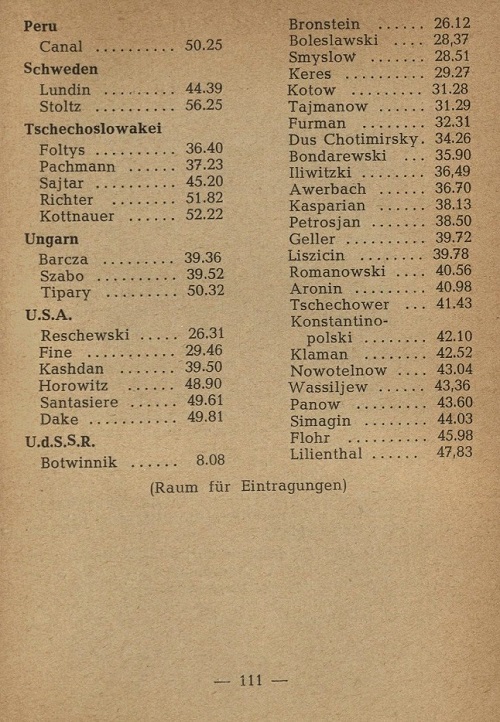

Below is the feature mentioned by CHESS, on pages 94-96 of Schach-Taschen-Jahrbuch 1966 edited by Herbert Engelhardt (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966):

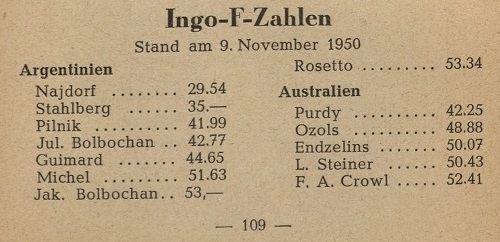

The Ingo system was also referred to briefly in a series of articles entitled ‘The International Chess Federation Rating System’ by Arpad E. Elo in CHESS, July 1973 (pages 293-296), August 1973 (pages 328-330) and October 1973 (pages 19-21). See too pages 16 and 143-144 of Elo’s book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present (London, 1978).

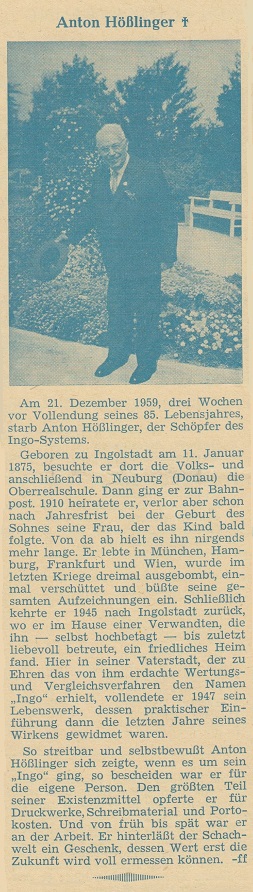

In a list of bibliographical references on pages 295-296 of the July 1973 CHESS Elo gave ‘Hesslinger [sic]; Ingo System; Bayrischen [sic] Schachnachrichten April 1948’. On pages 143-144 of his book Elo wrote: ‘The Ingo System, designed by Anton Hoesslinger of Ingolstadt, Germany, was described in Bayerische Schacht [sic], 1948, and by Herbert Englehardt [sic] (Englehardt [sic] 1951).’

The absence of Hößlinger’s name from the various German-language features is to be noted. The Ingo system was introduced in a series of articles in the Bayerische Schachnachrichten: April 1948, page 14; May 1948, page 19; June 1948, page 21 and page 22; July 1948, page 26.

We also present the article ‘Das Ingo-System’, in the Schach-Taschen-Jahrbuch 1951 edited by Herbert Engelhardt (Berlin-Frohnau, 1951), on pages 105, 106, 107, 108 and 109. It was followed by these rankings on pages 109-111:

Acknowledgement for the articles in the Bayerische Schachnachrichten and the Schach-Taschen-Jahrbuch 1951: the Cleveland Public Library.

Mention may also be made of ‘Problems of Rating and BCF/INGO Grading’ by Professor H. Schreiner on pages 110-111 of the BCM, March 1991.

Finally, the obituary of Anton Hößlinger on the inside front cover of Schach-Echo, 20 January 1960:

(10414)

Note (20 December 2020): This article, much shorter, was previously entitled ‘Chess Ratings and Titles’. The removal of the last two words reflects the fact that a small number of items previously included here have been transferred to Chess Grandmasters.

See too Warriors of the Mind.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.