Edward Winter

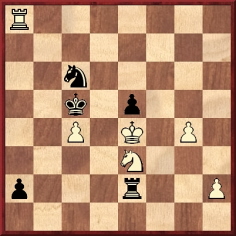

L’Echiquier, February 1928, page 838 (C.N. 10806)

**

From page 391 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

In La Nación in 1930 Alekhine described Flohr as ‘the second true talent to have emerged in the chess world since the War (the first was the Mexican Torre)’. The world champion also predicted ‘an exceptional chess future’ for Flohr.

Source: El Ajedrez Americano, August 1930, page 227.

The BCM, May 1928 (page 223) has a game played by Carlos Torre and Concepción Torre versus Egidio Torre and Raúl Torre. The source is the Mexican journal Boletín de Ajedrez, which had the caption ‘The Torre Family in Action’. An ultimate, one would assume, for a game involving a well-known master.

(1117)

Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) draws attention to a passage on page 5 of a book published by Kalnājs on the Chicago, 1973 tournament:

‘Carlos Torre, a young unknown chessplayer from distant exotic Mexico, was the greatest threat to the leading grandmasters in Moscow’s international tournament of 1925. Here is one example of his play. Because of Moscow’s freezing winter climate, after a short time illness felled Carlos Torre prematurely at the age of 29.’

Since Torre died in 1978 ... it is the Kalnājs book that felled him prematurely.

(2411)

‘According to H.A. Horwood of Los Angeles, Cal., in the October “Folder” of the Good Companion Chess Problem Club, Carlos Torre, R., the boy expert of New Orleans, like Rzeschewski, has appeared in the “movies”.’

Source: American Chess Bulletin, November 1920, page 176.

No further information has yet been found, and for now we can but add the exact text in the earlier publication:

‘H.A. Horwood, Los Angeles, Calif. “These are wonderful days for chess, as I saw last evening, in a moving picture theatre, an exhibition of our boy wonder, C. Reperto [sic], of New Orleans.”’

Source: “Our Folder”, 1 October 1920, page 11.

(4862)

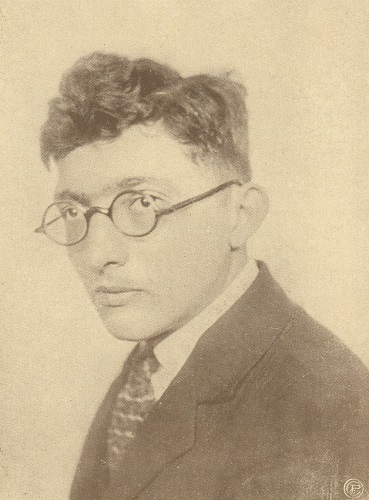

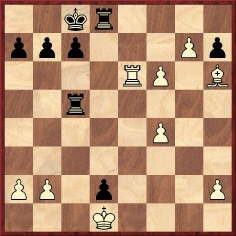

A game from page 236 of the September 1957 BCM:

C. Chaurang (France) – B.J. Moore (England)1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5 e6 7 Qd2 a6 8 O-O-O h6 9 Bf4 e5 10 Nxc6 bxc6 11 Bxe5 Bg4 12 Bxf6 Qxf6 13 Be2 Be6 14 f4 Be7 15 Rhe1 O-O 16 Bf3 Rab8 17 e5 dxe5 18 fxe5 Qh4 19 Ne4 Bd5 20 Kb1 Qxh2 21 Re2 Qxe5 22 Nc3

22…Rxb2+ 23 Kxb2 Rb8+ 24 Ka1 Ba3 25 Rxe5 Bb2+ 26 Kb1 Bxc3+ 27 Kc1 Bb2+ 28 Kb1 Bxe5+ 29 Kc1 Bb2+ 30 Kb1 Bc3+ 31 Kc1 Bxd2+ 32 White resigns.

On page 295 of the November 1957 BCM D.J. Morgan quoted W. Ritson Morry’s view in the Chess Supporter that this game surpassed Torre v Lasker, Moscow, 1925, for the following reasons:

‘(a) The pieces which enable the discovered check seesaw to be operated are not on the immediate scene as in the Torre game.

(b) Two sacrifices, and not one, are necessary to make the plan work properly.

(c) The quiet 24th move by the king’s bishop was not easy to foresee.

(d) The operation extends over a much greater area of the board and is accomplished with much greater concealment of intention.’

(2900)

See also The Chess Seesaw.

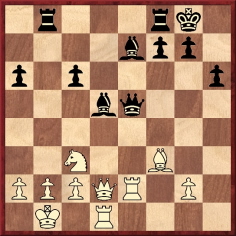

Nowadays, Chess Fever is widely available for home viewing.

(3987)

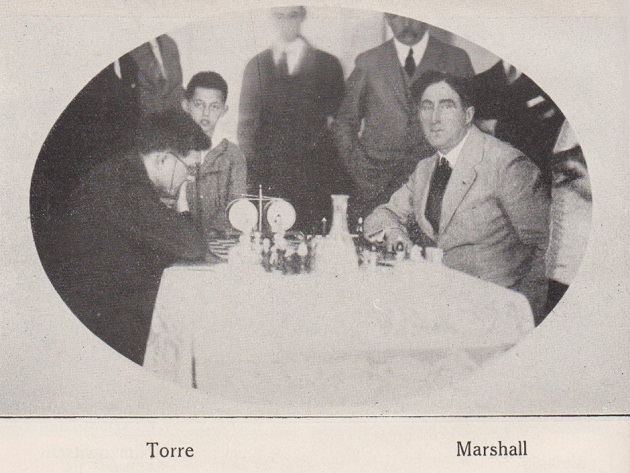

It may be noted that the set of pairings filmed (e.g. Marshall v Torre and Réti v Yates) corresponds to no round of play at Moscow, 1925, and there is much artificial smiling for the camera.

(3992)

Filiberto Terrazas Sánchez’s book La guerra apache en México was first published in 1972.

As mentioned on pages 8-9, in 1962 Terrazas wrote El águila caída, a biographical novel concerning Carlos Torre.

(4049)

See C.N. 5767 below.

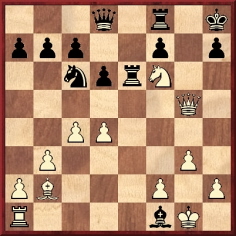

C.N. 2872 discussed the game Torre v Parker (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 O-O Bc5 6 e5 d5 7 exf6 dxc4 8 Re1+ Be6 9 Ng5 Qd5 10 Nc3 Qf5 11 Nce4 O-O-O 12 g4 Qe5 13 Nxe6 fxe6 14 fxg7 Rhg8 15 Bh6 Bd6 16 f4 Qa5 17 Qf3 Qd5 18 g5 Bc5 19 Kg2 Be7 20 Nf6 Bxf6 21 Qxd5 Rxd5 22 gxf6 Rf5 23 Rxe6 Nd8 24 Rae1 Nxe6 25 Rxe6 d3 26 cxd3 cxd3 27 Kf2 d2 28 Ke2 Rd8 29 Kd1 Rc5 30 White resigns), which became famous because in the final position ...

... Torre could have won with 30 Rd6.

See pages 5-6 of Chess Facts and Fables, but our book should have included the following supplementary information from Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) which appeared in C.N. 2874:

‘It seems that the game was played on 16 September 1924.

“In his first simultaneous exhibition at the rooms of the Marshall Chess Club Tuesday evening, Carlos Torre was opposed by ten players. After two hours and 30 minutes the Western champion finished with a score of eight wins and two losses. The winners were Z.L. Hoover, secretary of the Correspondence Chess League of America, and F. Parker, former champion of the Marshall Chess Club.” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 September 1924, page A3.)

The next week’s column (25 September 1924 issue, page A3) gave the game with this introduction:

“Befitting a modest young man, Torre does not believe in concealing the successes of opponents, which are rare enough, goodness knows, under a bushel. A case in point, and quite a strange incident, is his game with F.E. Parker in his simultaneous exhibition at the Marshall Chess Club, where Torre won eight and lost two. After 29 moves the young Mexican resigned. He had no sooner done this than it flashed across his mind that he had missed a good reply, but, having given up the game, he allowed the decision to stand. Further examination showed that he actually had a winning continuation in hand.”

Then the score is given (just as you have it) followed by this note:

“Instead of resigning, White could have won by force as follows: 30 R-Q6 (a real problem move) RxR 31 P-Kt8(Q)ch K-Q2 32 Q-B7ch K-B3 33 Q-K8ch K-Kt3 34 Q-K3 and wins. If 32...K-Q 33 Q-B8ch K-Q2 34 QxRch PxQ 35 P-B7 and wins.”

A footnote came a few weeks later (30 October 1924, page A3):

“With reference to the game which Frank E. Parker won from Torre in the latter’s simultaneous exhibition at the Marshall Chess Club, it should be stated, in justice to Mr Parker, that it was he who was the first to point out the problem move by means of which his opponent might have won the game he actually resigned.”’

Carlos Torre

(4422)

This game was published on page 219 of the December 1924 American Chess Bulletin:

William Allen Ruth – Newell Williams Banks

Western Tournament, Detroit, 1924

English Opening

(Notes by Carlos Torre)

1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 e5 3 g3 d6 4 Bg2 Be7 5 e3 Nc6 6 d4 exd4 7 exd4 O-O 8 Nge2 Bf5 9 O-O Qd7 10 b3 Rae8 11 Nf4 Bd8 12 Bb2 g5 (‘Of course this is too bold. Black has reached a point where he cannot conceive any plan of action. The manner in which White takes advantage is highly artistic.’) 13 Nfd5 Bh3 14 Qf3 Bxg2 15 Nxf6+ Bxf6 16 Qxf6 Re6 17 Nd5 Bxf1 18 Qxg5+ Kh8 19 Nf6 Qd8

20 d5 Ne5 21 dxe6 Nf3+ (‘Of course if 21...fxe6 22 Kxf1 and f4.’) 22 Kxf1 Nxg5 23 e7 (‘But first 23 Nd5+ would have won without much difficulty.’) 23...Qxe7 24 Nd5+ Qe5 25 Bxe5+ dxe5 26 Nxc7 Nf3 27 Kg2 (‘27 Rd1 was very promising, for if 27... Nd4 then 28 Nb5.’) 27...Nd4 28 Re1 f6 29 Nd5 (‘29 f4, at once, was also possible.’) 29...Kg7 30 Re4 b5 31 f4 bxc4 32 fxe5 fxe5 33 bxc4 Nc6 34 Rg4+ Kf7 35 Rh4 Kg6 36 Rg4+ Kf7 37 Re4 Rb8 38 Re2 Rb1 39 Rf2+ Kg7 40 Kf3 Rc1 41 Ne3 Kf6 42 Ke4+ Ke6 43 Rf5 Ra1 44 Rh5 Kd6 45 Nd5 Kc5 (‘Not 45...Rxa2 at once, for then 46 Rh6+ and 47 Rxc6+. Black is making the most of it.’) 46 Rh6 (‘In the hope of catching Black, he again wastes valuable time. 46 Rxh7 at once and g4 should have been played.’) 46...a5 47 Ne3 Rxa2 48 Rxh7 a4 49 g4 a3 50 Rh8 Re2 51 Ra8 a2

52 g5 Kb4 53 g6 Na5 54 g7 a1(Q) 55 g8(Q) Qd4+ 56 Kf5 Rxe3 57 Qb8+ Kxc4 (‘White has, of course, mismanaged the endgame sadly. Now Black good-naturedly takes the pawn. 57...Kc3 would probably have won. Let us say, 58 Rxa5 Rf3+ 59 Ke6 Qg4+, winning easily.’) 58 Qc7+ Drawn. (‘For if 58...Kd3 59 Rd8. Or 58...Kb3 59 Rb8+. A very interesting and instructive game.’)

(4986)

Dale Brandreth asks what basis exists for the following claims about Carlos Torre on page 425 of the Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1992):

‘At Chicago later that year, just before the last round of the Western championship (in which he tied for second place), Torre received two letters by the same post, one informing him that he would not get the teaching post for lack of academic qualifications, and the other from his fiancée saying she had married someone else. He suffered a nervous breakdown, returned to Mexico at the end of the year, took an ill-paid job in a drug-store, and played no more serious chess.’

Carlos Torre

(5759)

From Taylor Kingston (Shelburne, VT, USA):

‘In 1999, I worked with Gabriel Velasco on an English version of his book Vida y Partidas de Carlos Torre (Mexico City, 1993). It was published as The Life and Games of Carlos Torre (Milford, 2000). In my role as translator/editor I naturally compared Velasco’s work with other sources, including the entry on Torre in the Oxford Companion to Chess. I first noticed a minor error in the Companion’s account: the 1926 Chicago tournament at which the episode of the letters supposedly occurred was not the “Western championship”. The tournament in which Torre played Edward Lasker was the Chicago Masters. See page 111 of the September-October 1926 American Chess Bulletin.

A more significant difference was that the Companion’s tale of the emotionally painful letters which Torre supposedly received before his game with Lasker was conspicuously absent from Velasco’s account. When I asked him about this, he expressed the opinion that the letters never existed. He pointed to two big improbabilities: one, that the Mexican government would offer financial support to a chessplayer, and two, that Torre, who was not noted for romantic involvement with women, would have been engaged.

Velasco also pointed out that Filiberto Terrazas’ novel El águila caída, written in 1962 and based on Torre’s life, featured the letters story prominently. Velasco regarded that book as more fiction than biography, and the episode of the letters as just one of its romantic embellishments. And I was struck by the fact that Terrazas’ tale of heartbreak closely mirrored another fictionalized biography, Frances Parkinson Keyes’ The Chess Players (1960), based on the life of Paul Morphy, in which a refused marriage proposal contributes to Morphy’s withdrawal from chess. Therefore, before the discussion of the Torre v Lasker game in The Life and Games of Carlos Torre we added a passage highly skeptical of the letters’ existence (see page 281).

It is perhaps a pity that Velasco did not ask Torre about all this in his 1977 interview, but there is Torre’s statement,“After the tournament in Chicago, in 1926, my health was shattered due to dietary difficulties. In fact, I suffered a nervous breakdown.” (See page 292 of The Life and Games of Carlos Torre.)

I asked Kenneth Whyld what sources he had used for the Torre entry in the Companion. At first he was unable to supply specifics, saying that some 20 different sources were consulted, some contradictory, and that it was a perennial problem for an encyclopedist to know which to believe. In further correspondence, however, he mentioned a source that not only referred to the letters but even gave a name to the supposed faithless fiancée: Susanna. The writer of this information? Gabriel Velasco himself.

What happened is this: Velasco began working on his Torre book in the 1970s. He consulted Whyld at that time about the possibility of an English edition, even sending him the manuscript. At that early point in his research, Velasco believed Terrazas’ story of the letters and the jilting fiancée, and had treated them as fact in his MS. Whyld then took this as an authoritative source. By the time the Companion was published, Velasco and Whyld were no longer corresponding, so Whyld never learned of Velasco’s change of mind until I contacted him in 1999.

I have confirmed all this recently with Velasco. On 18 September 2008 he wrote to me:

“I consider the Oxford Companion account false, in view of the testimony which was told direct to me by the late dean of chess in Mexico, Alejandro Báez Graybelt, who was the most reliable source for everything concerning Torre’s life. Señor Báez assured me that the story was merely an invention, or, as you called it once, ‘a story typical of a paperback novel’. What is true, of course, is that Torre suffered a nervous breakdown, returned to Mexico at the end of the year, took an ill-paid job in a drug-store, and played no more serious chess.”’

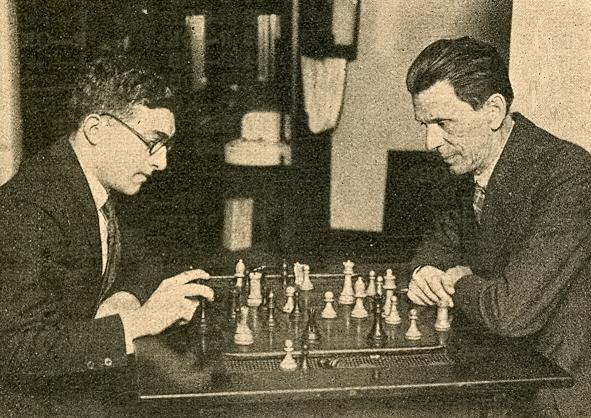

Carlos Torre and Géza Maróczy, Chicago, 1926 (American Chess Bulletin, November 1926, page 140)

(5767)

A second revised and expanded edition of the Torre monograph was published by Thinkers Publishing in 2023.

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) writes regarding the suggestion in the Oxford Companion to Chess that Carlos Torre’s nervous breakdown was prompted by receipt of two distressing letters, just before his last-round game against Edward Lasker at Chicago, 1926.

In Hermann Helms’ chess columns in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 1926-27 Mr Urcan has found no mention of such an incident in relation to the tournament, which Helms attended. On 26 October 1926 Helms gave some details of Torre’s return to Mexico:

‘Carlos Torre, Mexican chess champion, sailed Saturday on board the steamship Monterey of the Ward Line bound for his home in Mérida, Yucatán, by the way of Havana and Progreso. The young international expert returned to this country a little over two months ago in order to play in the national tournament at Chicago, where he finished second on a level with Maróczy of Hungary and just below Marshall, the United States champion. Since his return to New York Torre has been in poor health and has gone home to rejoin his parents. In the milder climate of his native land he hopes for speedy recuperation.

Antonio Canto, another native of Mérida, and Emilio Deymier, both members of the Philidor Chess Club of this city, were passengers on the same ship. Before leaving Mexico City, where he won the national chess championship in a tournament, Torre obtained strong backing for a match with Marshall for the pan-American championship, but negotiations that were set afoot were discontinued.’

Carlos Torre

Moreover, Helms obtained some details by interviewing F.C. Lona. From the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 26 May 1927, page 16:

‘Torre Regaining Health

Carlos Torre, who suffered a breakdown several months ago and returned home to his parents in Mérida, Mexico, has regained his health, according to F.C. Lona of Manhattan, Mexican railway and press representative and a personal friend of the young Mexican chess champion. “He was aware that his health was failing him”, said Mr Lona, “when he noticed that he had to over-exert himself in capturing the Mexican championship and later, when in Chicago, he had to lash himself to the utmost to bring forth his best in the masters’ tournament in which he came out second. Then, instead of taking a much needed rest as soon as he arrived in New York, he devoted himself to translating Dr Lasker’s book Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, which task, Torre asserts, proved to be gigantic and constituted the traditional straw.

He is now gaining on weight and in general physical health and believes that he will be fit to compete in the next Mexican chess championship during June. If, after that championship, he feels confident that he has become his old self as a chessplayer, he intends to step out into the world and continue his chess career as an internationalist.

Torre’s many friends here feel that he will be well advised if he abstains entirely from serious chess for another year and then, fully reinvigorated perhaps, re-enter the arena which gave him world-wide fame.’

What further information can be found, and not least about the translation matter?

(6485)

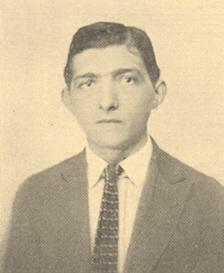

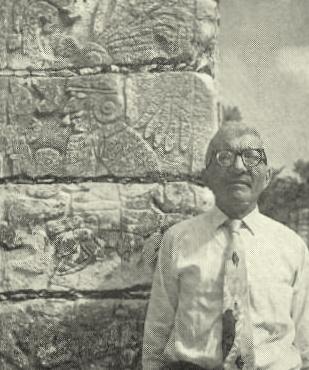

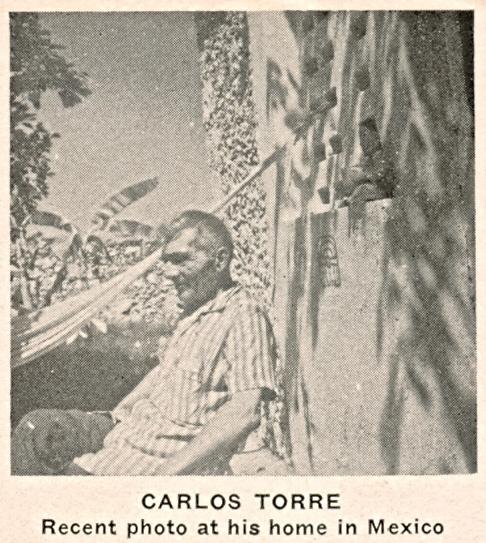

C.N. 5759 gave a rare photograph from Carlos Torre’s later years, and below is another one:

Source: Chess Review, June 1964, page 165.

(6765)

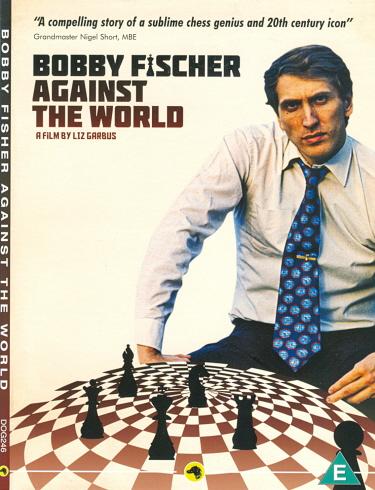

Graced with some exceptionally rich archive material, Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World is disgraced with some exceptionally poor interviewees. A particular low point, with some of the talking heads less concerned about being truthful than noticed, is the dense sequence which seizes on the issue of insanity:

...

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Carlos Torre took all his clothes off on a bus.’

(7345)

See ‘Fun’ and Chess and Insanity.

From an article by Fred Reinfeld about Alexander Kevitz on pages 25-26 of the April 1946 Chess Review:

‘He credits much of his early interest and rapid progress to Mason’s Principles of Chess. (Years ago, by the way, the famous Mexican player Carlos Torre told me in almost the same words of his great debt to Mason’s books. Mason was not only a master of clear exposition; he also knew how to kindle the reader’s interest and how to stimulate his curiosity.)’

(9610)

From the Marienbad, 1925 tournament book:

(9844)

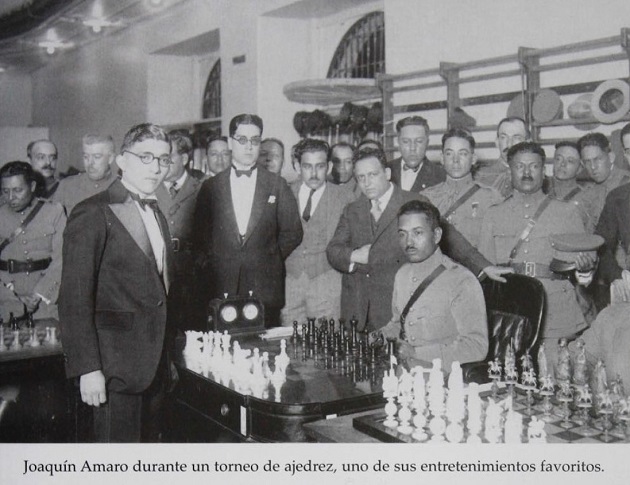

This photograph has been sent to us by Doug Geib (Brecksville, OH, USA), who obtained it when he acquired the chess set, table and clock in front of which Carlos Torre is standing. Joaquín Amaro Domínguez was a leading Mexican military figure. Information is sought concerning the simultaneous display in question.

(10304)

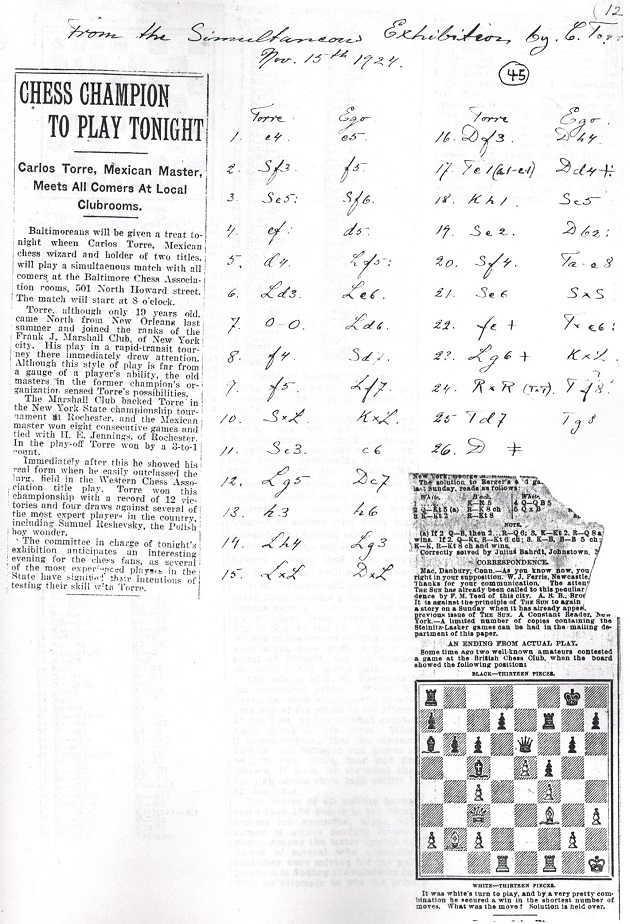

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) sends this win by Carlos Torre from the scrapbook published by Dale Brandreth which was discussed in C.N. 2996 (see page 51 of Chess Facts and Fables):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nxe5 Nf6 4 exf5 d5 5 d4 Bxf5 6 Bd3 Be6 7 O-O Bd6 8 f4 Nbd7 9 f5 Bf7 10 Nxf7 Kxf7 11 Nc3 c6 12 Bg5 Qc7 13 h3 h6 14 Bh4 Bg3 15 Bxg3 Qxg3 16 Qf3 Qh4 17 Rae1 Qxd4+ 18 Kh1 Nc5 19 Ne2 Qxb2 20 Nf4 Rae8 21 Ne6 Nxe6 22 fxe6+ Rxe6 23 Bg6+ Kxg6 24 Rxe6 Rf8 25 Re7 Rg8 26 Qf5 mate.

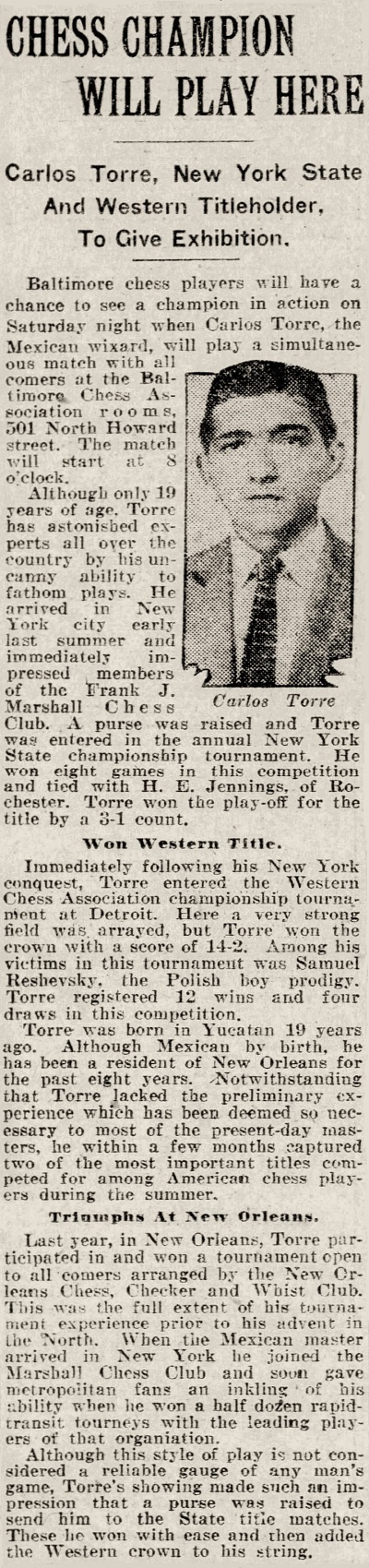

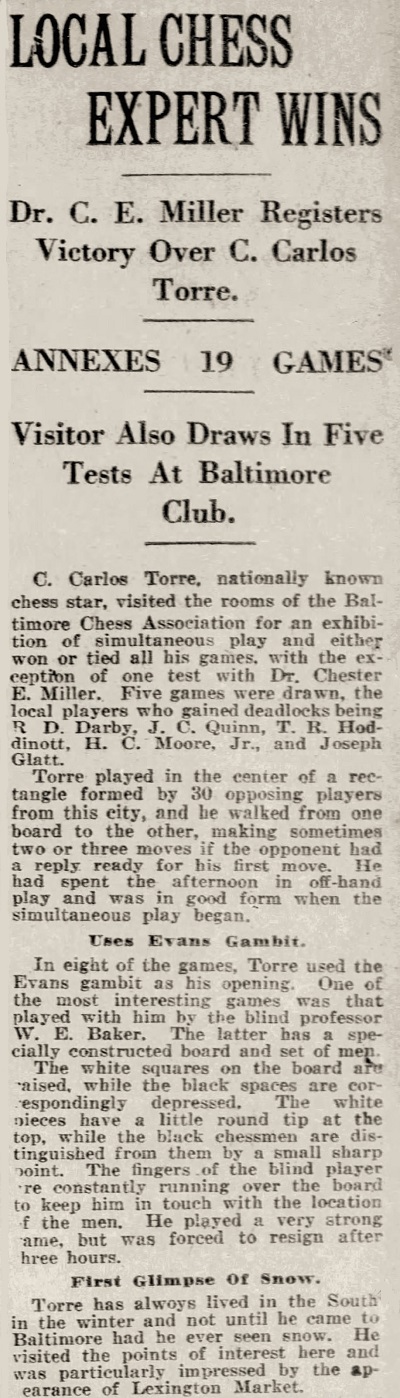

We add that the above announcement about Torre’s display was on page 11 of the Baltimore Sun, 15 November 1924. Two further reports from that newspaper:

Baltimore Sun, 11 November 1924, page 16

Baltimore Sun, 17 November 1924, page 8

As so often, there are statistical discrepancies, and page 217 of the December 1924 American Chess Bulletin misdated the exhibition and had a strange reference to J.C. Moore Jr:

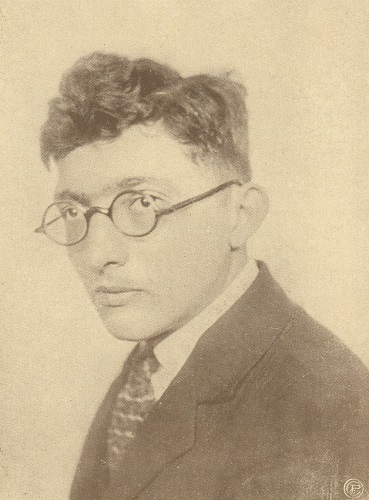

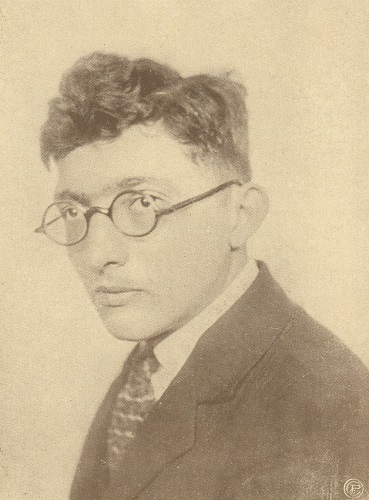

The photograph below is from opposite page 838 of the February 1928 issue of L’Echiquier:

Carlos Torre

(10806)

Detroit was the venue for the 25th Western Chess Association Tournament (23 August-2 September). The prodigy Reshevsky, his days as a touring Wunderkind behind him, came fifth, and it was the 18-year-old Carlos Torre who emerged victorious from the 17-man field, by a two-and-a-half point margin.

Carlos Torre

The July-August American Chess Bulletin (page 156) remarked that ‘Carlos Torre, the young Mexican expert, who for several years has made his home in New Orleans, where he outranked all others in interest in chess, recently came to New York and affiliated himself with the Marshall Chess Club. Like Capablanca, he has shown himself to be almost invincible in rapid transit play, although primarily he prefers slow, studious play.’ On pages 166-170 of the September-October issue of the same magazine, C.S. Howell presented some of Torre’s best games and offered a challenging comment on the Mexican:

‘He lacks technique and for the sake of his chess future, I hope that he will not hasten too much in cultivating it. Acquired naturally and as a result of the experience of play, technique is a valuable asset but the attempt to acquire it before one’s ability to combine has been fully developed has stopped permanently the improvement of a good many young players.’

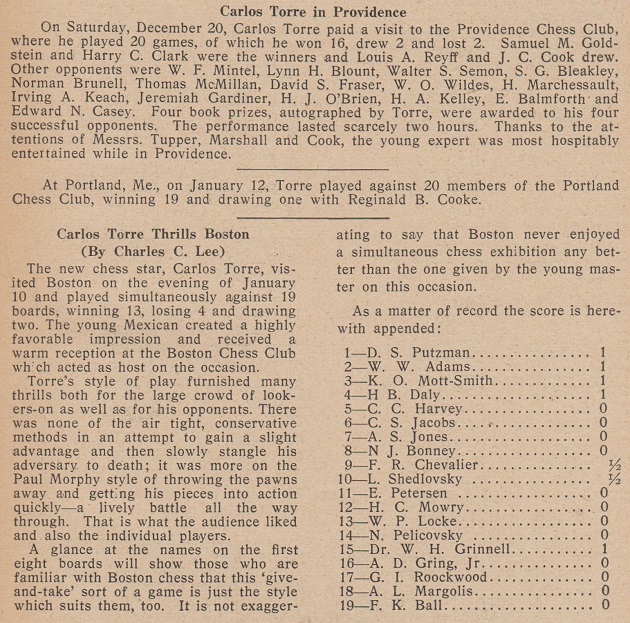

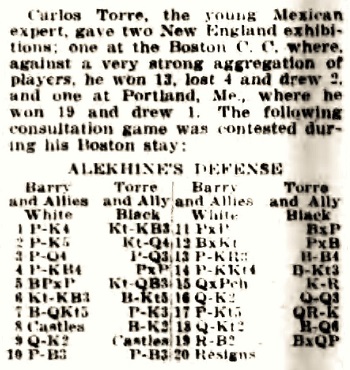

Few games played by Carlos Torre in simultaneous exhibitions are extant, and it has so far proved impossible to present anything worthwhile from the displays reported on page 7 of the January 1925 American Chess Bulletin:

(10829)

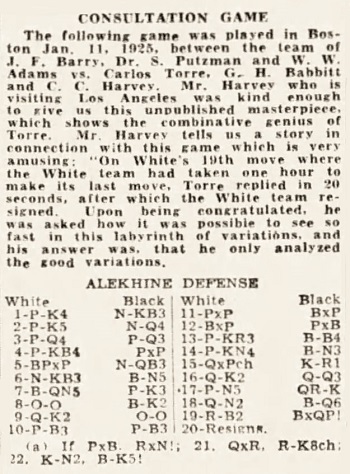

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) sends a consultation game (John Finan Barry, Weaver Warren Adams and Sigmund Daniel Putzman v Carlos Torre Repetto, George Harris Babbitt and C.C. Harvey) played in Boston on 11 January 1925:

Christian Science Monitor, 20 January 1925, page 16 (column by George H. Babbitt)

Los Angeles Times, 7 January 1945, page 12 (column by Herman Steiner)

1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Nd5 3 d4 d6 4 f4 dxe5 5 fxe5 Nc6 6 Nf3 Bg4 7 Bb5 e6 8 O-O Be7 9 Qe2 O-O 10 c3 f6 11 exf6 Bxf6 12 Bxc6 bxc6 13 h3 Bf5 14 g4 Bg6 15 Qxe6+ Kh8 16 Qe2 Qd6 17 g5 Rae8 18 Qg2 Bd3 19 Rf2

19...Bxd4 20 White resigns.

(10885)

From our feature article on the famous alleged game Adams v Torre:

We own a two-page letter which E.Z. Adams wrote to Hermann Helms, the editor of the Bulletin, on 22 November 1920 (page 1, page 2). We have no information on a draw against ‘Mr E. Laker of Chicago’ in 1920, but page 203 of the December 1921 American Chess Bulletin gave a loss by the Mexican (‘played between Carlos Torres [sic], 16 years old, and Edward Lasker of Chicago during the latter’s visit to New Orleans during November’).

C.N. 2781 gave that game:

Carlos Torre – Edward Lasker

New Orleans, November 1921

Ruy López1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 d4 b5 7 dxe5 dxe5 8 Qxd8+ Nxd8 9 Bb3 Bd6 10 Re1 c5 11 c4 Be6 12 Rd1 Ke7 13 Nc3 Rb8 14 Be3 Nc6 15 Nd5+ Bxd5 16 cxd5 Nd4 17 Bxd4 cxd4 18 Rac1 Rhc8 19 Bc2 Rc7 20 Bd3 Rbc8 21 Rxc7+ Rxc7 22 a4 bxa4 23 Ra1 a3 24 bxa3 Rc3 25 Bxa6 Nxe4 26 a4 f6 27 Bb5 d3 28 a5 Bc5 29 a6 Bxf2+ 30 Kf1 Ba7 31 Rd1 Nc5 32 Ke1

32…Rc2 33 Bxd3 Nxd3+ 34 Rxd3 e4 35 Rb3 exf3 36 Rb7+ Kd6 37 Rxa7 fxg2 38 Rxg7 Ra2 39 h4 Kxd5 40 a7 Ke4 41 Rg8 Kf3 42 White resigns.

For F.J. Marshall’s book Chess Masterpieces (New York, 1928), the world’s leading masters (and a few others) nominated their best game. On page 48 Edward Lasker put forward his win as Black over Torre, Chicago, 1926.

See The Best Chess Games.

See also Schuster v Carls.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.