Edward Winter

John S. Hilbert is one of the finest chess historians. His 354-page work Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster (Caissa Editions, 1997) was of exceptional quality, and we eagerly await his forthcoming books on two contrasting figures from US chess history, the irreproachable Walter Penn Shipley and the irredeemable Norman Tweed Whitaker.

(2406)

In 2000 an article by John S. Hilbert was posted at the Chess Archaeology website: ‘Norman Tweed Whitaker and the Search for Historical Perspective: A Tale Full of Genius and Devil’.

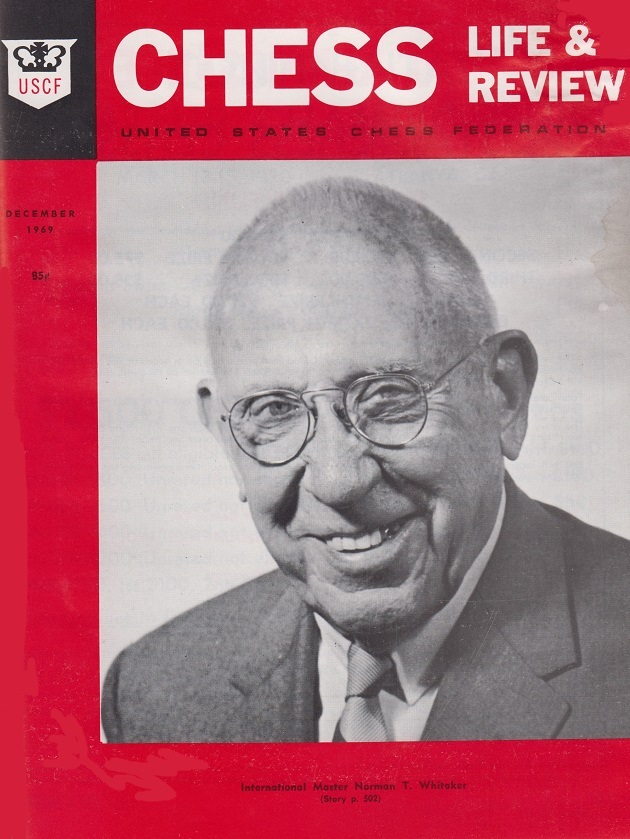

The book mentioned in C.N. 2406 has now been published, under the title Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chessmaster by John Hilbert (Caissa Editions). Deeply researched, it is an enthralling romp through tournament halls, court-rooms and prison cells.

(2445)

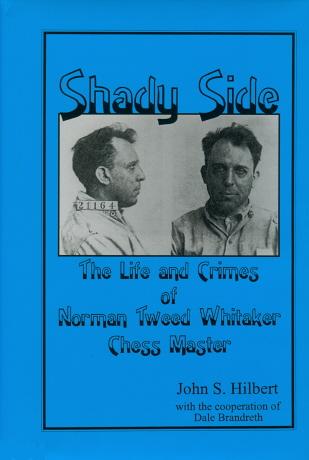

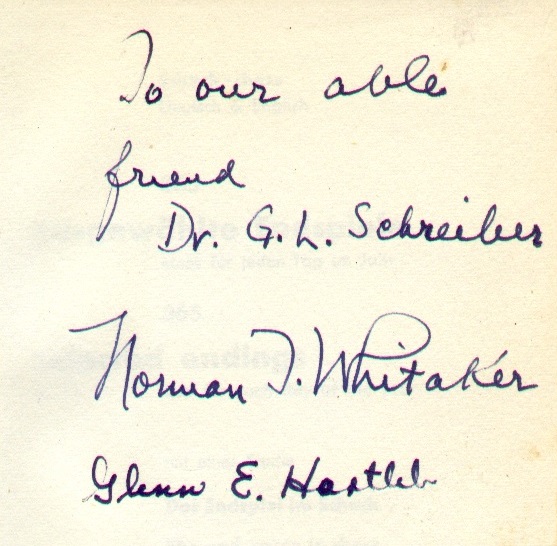

The two signatures below are reproduced from our copy of the bilingual book Ausgewählte Endspiele/Selected Endings by Norman T. Whitaker and Glenn E. Hartleb (Heidelberg, 1960):

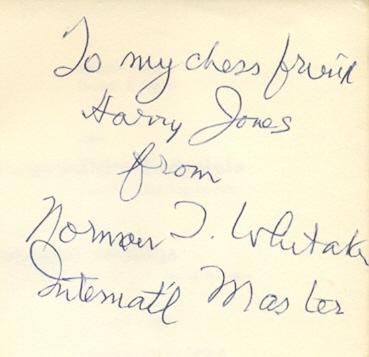

From another copy, inscribed by Whitaker:

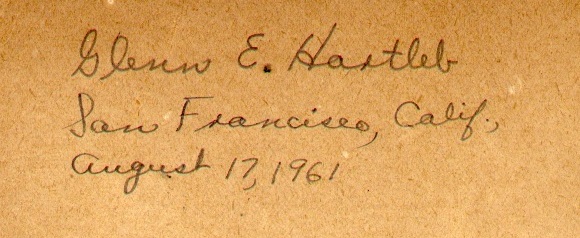

We also own a copy of the Berlin, 1926 tournament book (published by Kagan) which was inscribed by Hartleb on 17 August 1961, i.e. two weeks before he was killed in a road accident:

(2584)

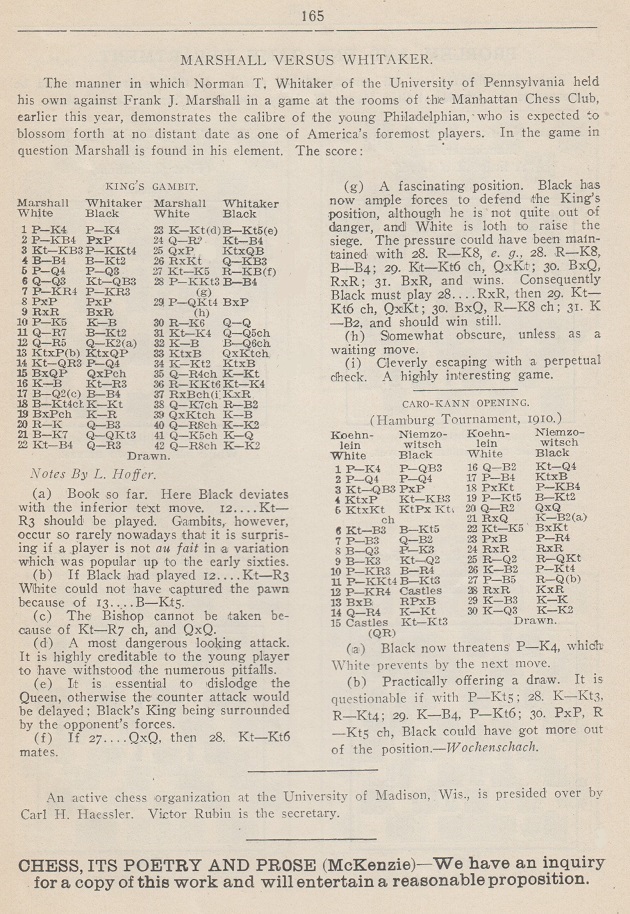

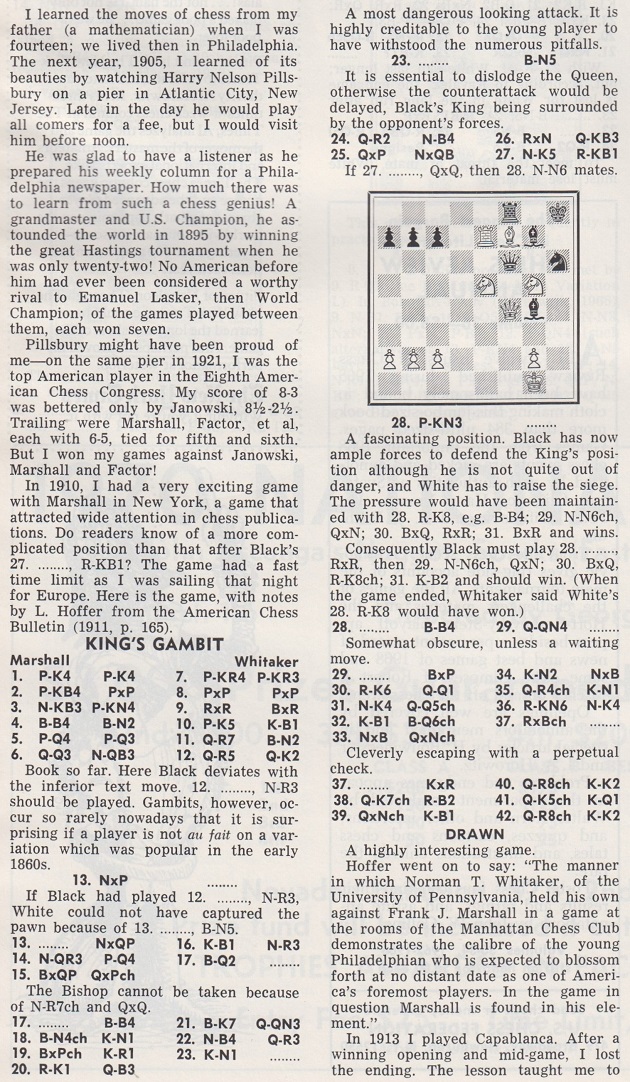

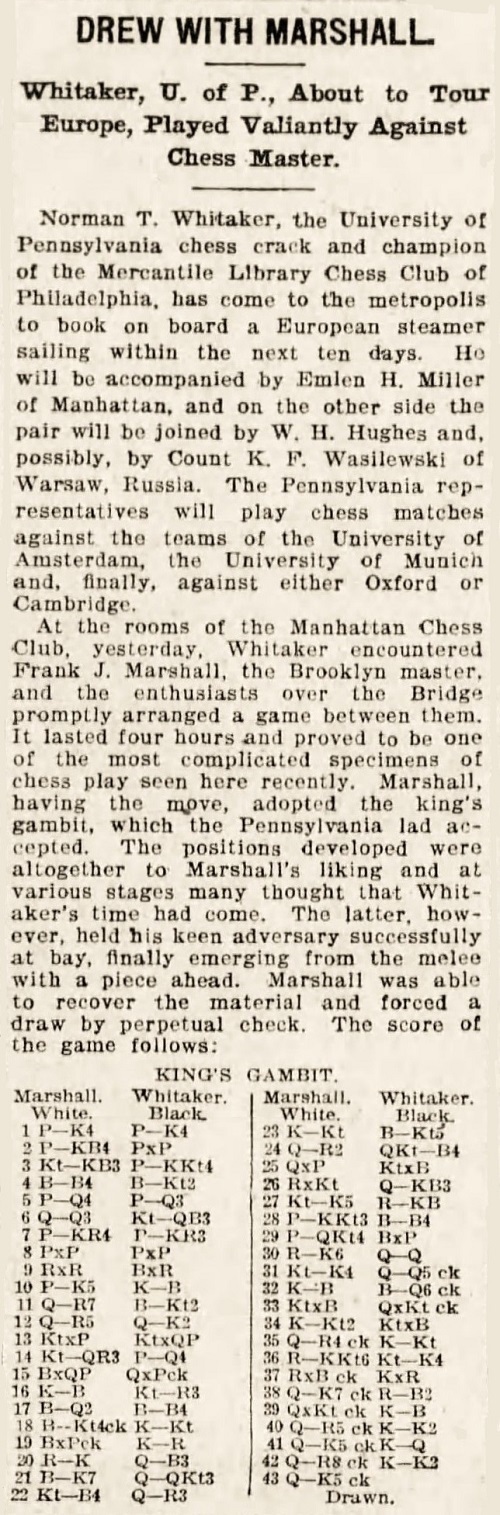

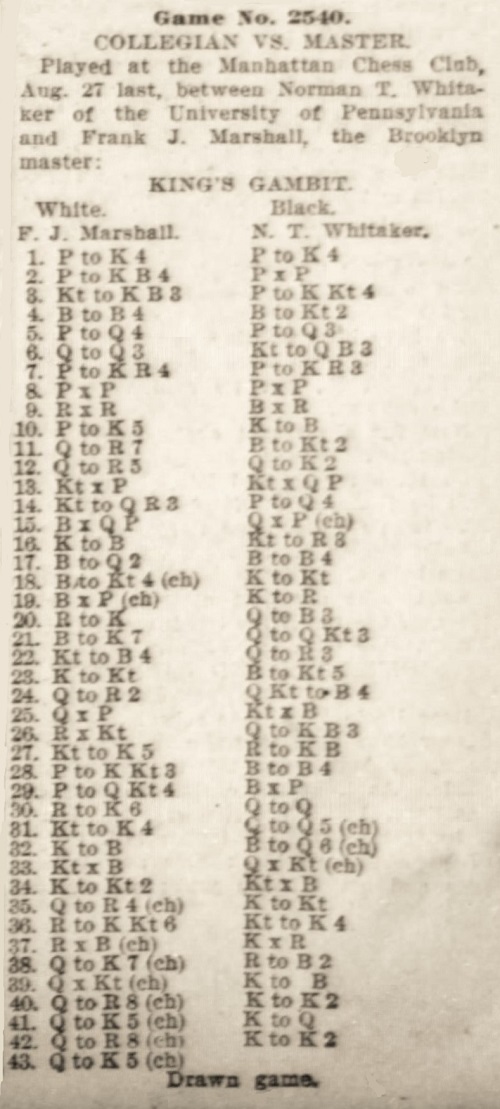

C.N. 2062 (see page 77 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) gave a Marshall v Whitaker game from page 165 of the July 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 5 d4 d6 6 Qd3 Nc6 7 h4 h6 8 hxg5 hxg5 9 Rxh8 Bxh8 10 e5 Kf8 11 Qh7 Bg7 12 Qh5 Qe7 13 Nxg5 Nxd4 14 Na3 d5 15 Bxd5 Qxe5+ 16 Kf1 Nh6 17 Bd2 Bf5 18 Bb4+ Kg8 19 Bxf7+ Kh8 20 Re1 Qf6 21 Be7 Qb6 22 Nc4 Qa6 23 Kg1 Bg4 24 Qh2 Nf5 25 Qxf4 Nxe7 26 Rxe7 Qf6 27 Ne5 Rf8 28 g3 Bf5 29 b4 Bxc2 30 Re6 Qd8 31 Ne4 Qd4+ 32 Kf1 Bd3+ 33 Nxd3 Qxd3+ 34 Kg2 Nxf7 35 Qh4+ Kg8 36 Rg6 Ne5 37 Rxg7+ Kxg7 38 Qe7+ Rf7 39 Qxe5+ Kf8 40 Qh8+ Ke7 41 Qe5+ Kd8 42 Qh8+ Ke7 Drawn.

The introduction stated that the game was played ‘earlier this year’, and we duly gave the date 1911, as did John Hilbert in his monograph on Whitaker (see pages 37, 324 and 350).

On page 502 of the December 1969 Chess Life & Review Whitaker put 1910:

In reality, the game was played in 1909:

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Sports Section), 28 August 1909, page 5

Times-Democrat, 19 September 1909, page 9.

Both newspapers gave one further move, 43 Qe5+.

A line given by Emanuel Lasker on pages 17-20 of his book Common Sense in Chess is 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 Re1 Nd6 6 Nc3 Nxb5 7 Nxe5 Be7 8 Nd5 O-O.

On page 192 of the July 1953 CHESS Norman Whitaker pointed out that instead of castling Black could remain a piece ahead by playing 8…Nbd4.

(2615)

Olaf Wolna (Hamburg, Germany) points out that on page 14 of the 1925 German edition (Gesunder Menschenverstand im Schach), Lasker himself remarked that with 8 Nd5 he had committed an oversight, because of 8…Nbd4. He therefore recommended 8 Nxb5 Nxe5 9 Rxe5 d6 ‘with a good game for Black’.

Concerning Whitaker’s observation on page 192 of the July 1953 CHESS, we are surprised by the magazine’s afterword: ‘Reinfeld’s revision of this book (1946) naturally omits this glaring blunder.’ In our copy, the ‘glaring blunder’ is still there (page 11).

(2631)

Now we have found that this error was already known in the nineteenth century. From page 246 of the December 1899 American Chess Magazine:

‘Attention is called by J. Biggs, of Bonham, Texas, to the following variation of the Ruy López, given both in Lasker’s Book and Freeborough’s Openings: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 Re1 Nd6 6 Nxe5 Be7 7 Nc3 Nxb5 8 Nd5 O-O. Mr Biggs played this line recently, but his opponent, instead of castling on the eighth move, played 8…Nbd4, with the result that Mr Biggs found himself with a clear piece down and no compensating attack. In bewilderment he applied for information. The move of 8 Nd5 by White is unsound and merely constitutes an oversight by the authorities named.’

(3208)

Our Interregnum article includes the following:

Another letter published by the BCM (April 1947 issue, pages 122-123) was from Norman T. Whitaker (‘Retired, undefeated, Champion National Chess Federation, USA’). Writing from Shady Side, MD on 24 January 1947 he declared:

‘When we analyse the fundamentals, however, the problem solves itself … for it is simple. May I, an old-timer, give my observations? I assert Dr Euwe is the chess champion of the world. Alekhine won it from him in 1937. On the death of Alekhine, last 24 March, the title automatically reverted to Euwe.’

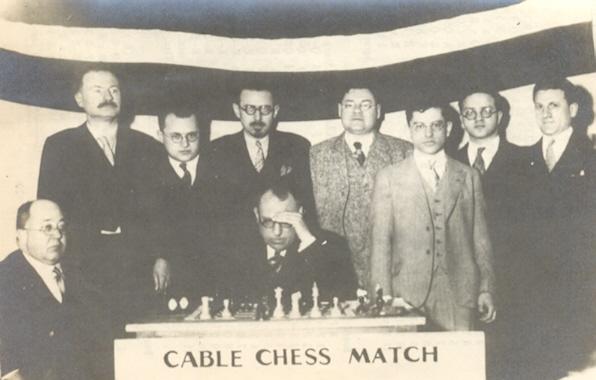

This group photograph appeared on page 19 of The Gambit, April-May 1931, the occasion being the Philadelphia v London cable match on 21 March 1931:

Seated (left to right): R.S.

Goerlich, N.T. Whitaker

Standing: S. Mlotkowski, D.G. Weiner, N.L. Lederer, S.T. Sharp,

J. Levin, H. Morris, B.F. Winkelman

(4182)

See too the photograph taken in The Hague, 1928:

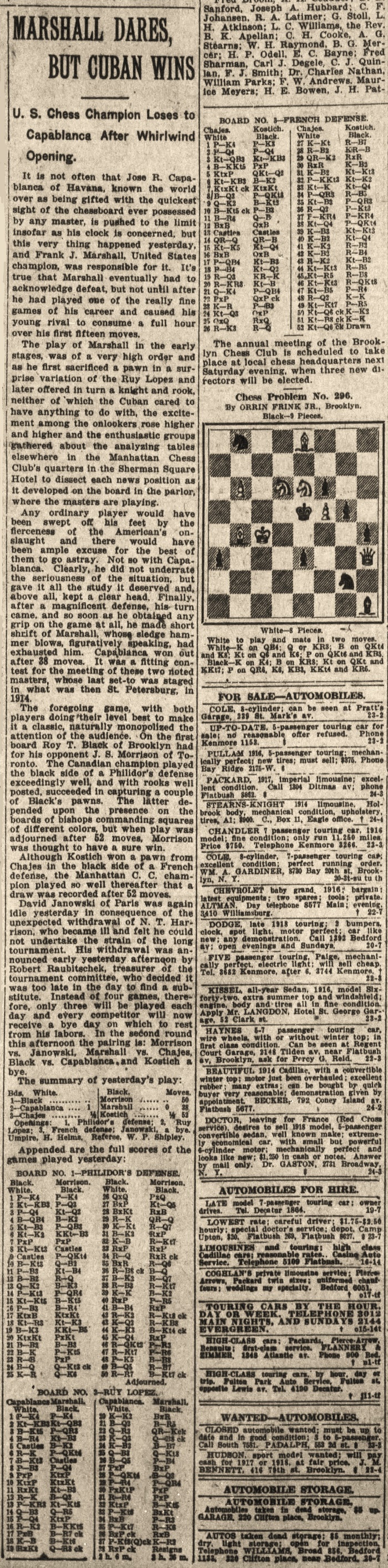

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) points out a report on page 12 of the New York Times, 24 January 1913 about the game between Whitaker and Capablanca in the New York tournament:

‘The result of this encounter was wholly contrary to general expectations, inasmuch as Whitaker, who had played really brilliant chess in the early stages of the game on Tuesday, was considered to have at least a draw in the adjourned position, with a chance of winning. After resumption of play yesterday, however, he played quite indifferently, though the position was an exceedingly difficult one to handle. He was eager to establish an advantage, and this led him to neglect providing a proper defense for his king.

Capablanca had sealed his 51st move, and this proved to be B-Q4. At his 56th turn he studied for 20 minutes, an indication that he, too, found the position one worthy of careful study. Finally, he appeared to have made up his mind, and placed his queen at QB6 without, however, relinquishing his hold upon the piece. Suddenly he switched away from that square and played the queen back to KKt8. Whether this manoeuvre served to distract his opponent in any way did not appear, but Whitaker nevertheless made a move which enabled the Cuban to win an important pawn through a check by discovery. This was inexplicable to the bystanders, who accepted it as a case of nervousness.

Later, Capablanca won the other of Whitaker’s centre pawns and then, getting out his rook, which had been bottled up for a long time, the Cuban soon had the game well in hand.

Whitaker resigned after 66 moves, when the black king rook’s pawn had been advanced to the seventh row and could not be stopped from queening. Thus was spoiled in the last dozen moves what might otherwise have ranked as a real masterpiece in the annals of the game.’

Here, for ease of reference, is the game-score, from page 55 of the March 1913 American Chess Bulletin:

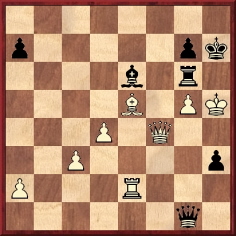

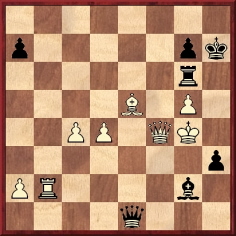

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bf4 e6 5 e3 Bb4 6 Bd3 c5 7 O-O c4 8 Be2 Bxc3 9 bxc3 Ne4 10 Qe1 Qa5 11 Nd2 Nxc3

12 Bxc4 Nc6 13 Nb3 Qb4 14 Bd3 Na4 15 Qe2 O-O 16 Qh5 f5 17 g4 Qe7 18 gxf5 exf5 19 Kh1 Nb2 20 Be2 Nc4 21 Nc5 b6 22 Qf3 bxc5 23 Qxd5+ Be6 24 Qxc6 Rac8 25 Qg2 cxd4 26 exd4 Qd7 27 c3 Rf6 28 Rg1 Rg6 29 Qh3 Bd5+ 30 f3 Rg4 31 Rxg4 fxg4 32 Qg3 Qf5 33 Rg1 h5 34 h3 Rf8 35 Bxc4 Bxc4 36 Bd6 Rf6 37 Be5 Rg6 38 Kh2 Bd5 39 Qf4 Qc2+ 40 Rg2 Qd3 41 hxg4 Bxf3 42 Rd2 Qf1 43 g5 Qh1+ 44 Kg3 Bd5 45 Rf2 h4+ 46 Kg4 h3 47 Rb2 Be6+ 48 Kh5 Kh7 49 Re2 Qd1 50 Qd2 Qg1 51 Qf4

51...Bd5 52 Rd2 Bg2 53 Kh4 Kg8 54 Rb2 Kh7 55 c4 Qe1+ 56 Kg4

56...Qg1 57 d5 Bxd5+ 58 Qg3 Be6+ 59 Kf3 Qf1+ 60 Ke3 Qxc4 61 Bd4 Qc1+ 62 Rd2 Bf5 63 Qh4+ Kg8 64 Be5 Re6 65 Qd4 h2 66 Qd8+ Kh7 67 White resigns.

The American Chess Bulletin gave Black’s 62nd move as B-B4, but instead of Bf5 some sources (e.g. the Weltgeschichte des Schachs volume on Capablanca) have put Bc4, a move that would leave the pawn at h3 undefended.

(5077)

Knud Lysdal (Grindsted, Denmark) asks whether further details are available about an episode reported by James E. Gates in his obituary of Norman T. Whitaker on page 521 of the August 1975 Chess Life & Review:

‘One of the stories about him concerned a US correspondence championship before World War II. A friend of his, who was competing in the tournament, suddenly died. His widow needed money, and this gave Norman the idea of finishing his friend’s games without letting anyone know. Whitaker wound up winning the tournament – the first, as far as I know, won by a dead man.’

Gates’ story was quoted on page 145 of the Whitaker monograph by John S. Hilbert.

(6318)

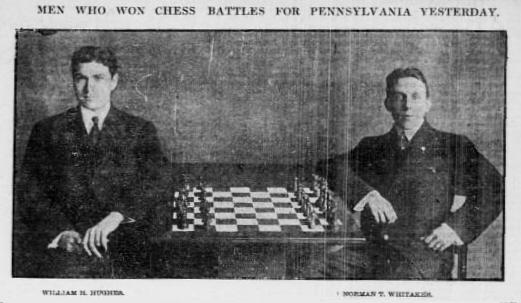

From Graham Clayton (South Windsor, NSW, Australia) comes this photograph on page 5 of the New York Tribune, 30 December 1908:

Concerning the event in question, see pages 10 and 344 of Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert.

(7106)

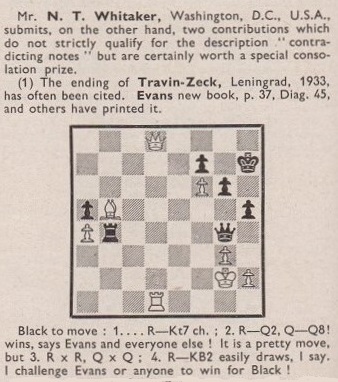

From page 192 of CHESS, July 1953:

(8977)

For a discussion of this position see A Chess Mess.

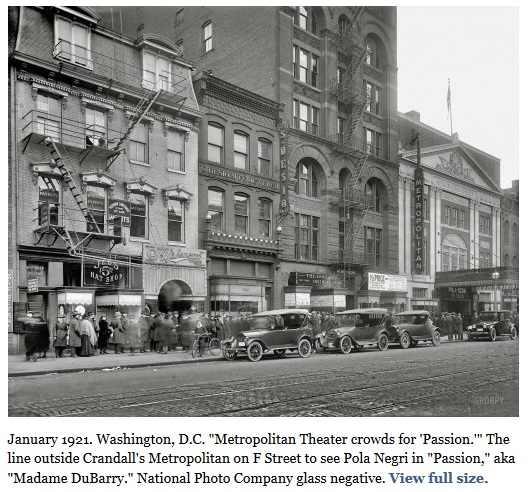

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) notes a 1921 photograph of Norman Whitaker’s offices in Washington, DC.:

This small version is reproduced with the permission of the Shorpy website. The large version shows many occurrences of Whitaker’s name.

(10207)

Wanted: examples of particularly negative chess obituaries, whatever the level of justification.

Norman T. Whitaker, one of the game’s leading reprobates, received little attention when he died in 1975. The obituary by his colleague James E. Gates on page 521 of the August 1975 Chess Life & Review was low-key:

‘Outside chess Norman was not very distinguished, being involved in too many things at and beyond the laws he studied.’

(11184)

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) writes:

‘After Whitaker’s death at 85 by stroke on 20 May 1975 at Cobb Memorial Hospital, Phenix City, Alabama, his friend and executor James E. Gates struggled to reconcile the late chessplayer’s finances. Ultimately, Whitaker’s assets did not quite satisfy his debts, and so he died a pauper. His death was largely ignored by the world, including the chess world, with one notable exception. The August 1975 Chess Life & Review obituary, written by Gates, as mentioned in C.N. 11184, avoided discussion of Whitaker’s life outside the game, and for good reason. His convictions for interstate auto theft (1924), conspiracy to defraud, along with Gaston B. Means, related to their hoax to swindle the owner of the Hope Diamond during the uproar of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping (1932), another auto theft (1932), sending narcotics through the mail (1944) and child molestation (1950) led to his spending time in Leavenworth and Alcatraz, along with a dreary host of lesser-known prisons and jails.

His papers, as I relate in detail in Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chess Master (Yorklyn, 2000), reveal his near-obsessive focus on a variety of other cons, ranging from ignoring parking tickets and failing to return hundreds of library books, to skipping out on debts, cheating friends and fiancées, and attempting extortion. Some of his actions were ludicrous, some quite petty, but many of them were disturbingly disclosing of an intelligent, amoral mind which, by almost any definition, uncovers a psychopath. Although he lost his law license after his first conviction, he never lost his gusto for suing, or threatening to sue, anyone and everyone on the flimsiest contortions of facts, including the USCF. His International Master’s title, awarded by FIDE in 1965, was as much a testimony to his years of pestering the officials involved as it was to his long-gone chess strength.

And yet especially during the roughly 20 years between 1910 and 1930, when not in prison, Whitaker excelled at playing chess. What he might have accomplished in the game, had he spent his time studying and playing it, instead of hatching one failed criminal plan and contentious lawsuit after another, can never be known. To borrow a few lines written regarding his one-time co-conspirator, Gaston B. Means, but that might equally apply to Whitaker, “Few men attain so much fame and so little success in so many kinds of crime, and at the same time acquire reputation of a sort in fields unrelated to their strict criminal activity.” (Quoted from the Christian Century in the Philadelphia Daily News, 28 September 1963, page 14.)’

(11212)

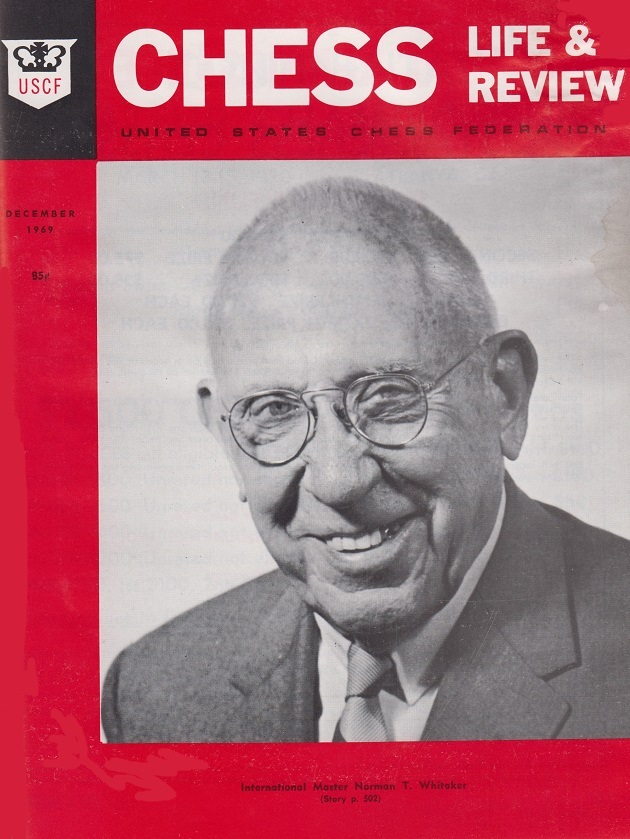

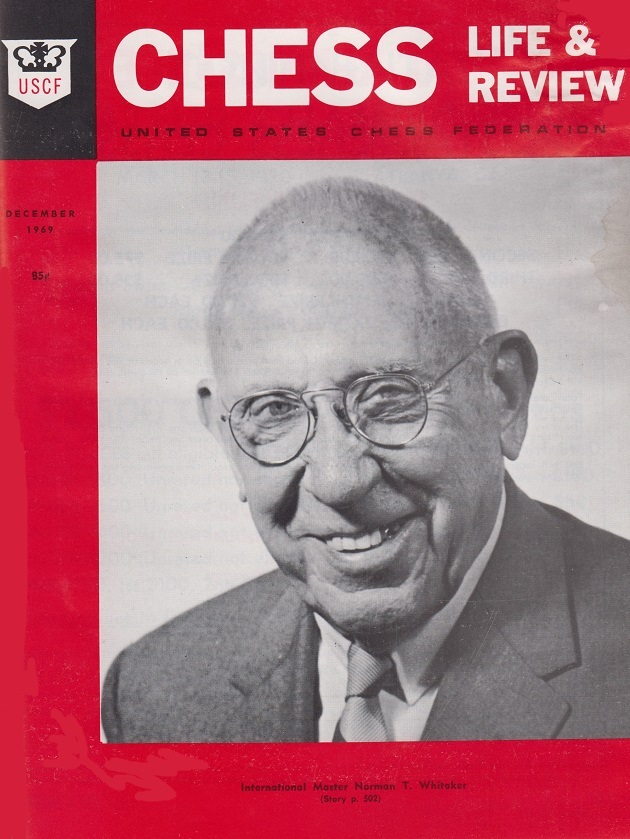

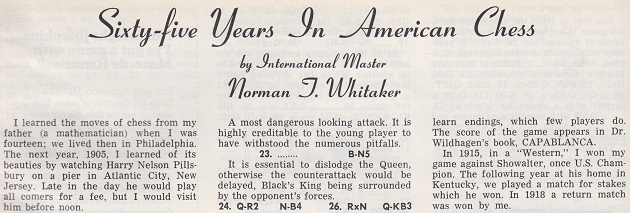

A lengthy autobiographical article by N.T. Whitaker was published on pages 502-504 of the December 1969 Chess Life & Review.

The chess accomplishments related included this curiosity (about which more information is sought):

‘In Hamburg, in May 1960, I drew a hard-fought six-game match with Grandmaster F. Sämisch, for stakes. We each won a game, with four draws. He is tough, as expected of a veteran master; he once defeated the dreaded Capablanca.’

Whitaker also showed ‘the only problem I ever composed’:

Mate in three.

Page 26 of the January 1970 issue gave the solution.

The extraordinarily convoluted preparation of Whitaker’s article for publication in Chess Life & Review is related on pages 281-285 of John Hilbert’s biography.

(11213)

C.N. 11213 asked for information about a contest referred to by N.T. Whitaker on page 503 of the December 1969 Chess Life & Review:

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) reports that he has traced no reference to such a match in either the Deutsche Schachzeitung or Schach-Echo of the time.

(11288)

The hundreds of entries in Chess and the Law An Anthology of Anecdotes and Analogies by Andrew J. Field (‘Amazon Fulfillment’, Wrocław, 2019) range from a brief paragraph on a minor court-case to four pages on Norman Tweed Whitaker and nine on William Henry Russ. An unnumbered introductory page states that the book ‘surveys the many interesting and unusual ways that the game of chess has intersected with the practice of law in the United States’ and warns that ‘this book is not appropriate for children’. Many violent cases are discussed.

(11681)

Just received: Bobby Fischer en Cuba by Miguel A. Sánchez and Jesús Suárez (‘Printed by Amazon Italia Logistica S.r.l., Torrazza Piemonte (TO), Italy’, 2019):

Far from diligently presenting fresh, worthwhile information, the book, sullied with an inordinate number of misspelt names, is mainly padding and irrelevancies. For example, pages 28-32 and pages 293-296 are taken up with games between Capablanca and Whitaker.

(11722)

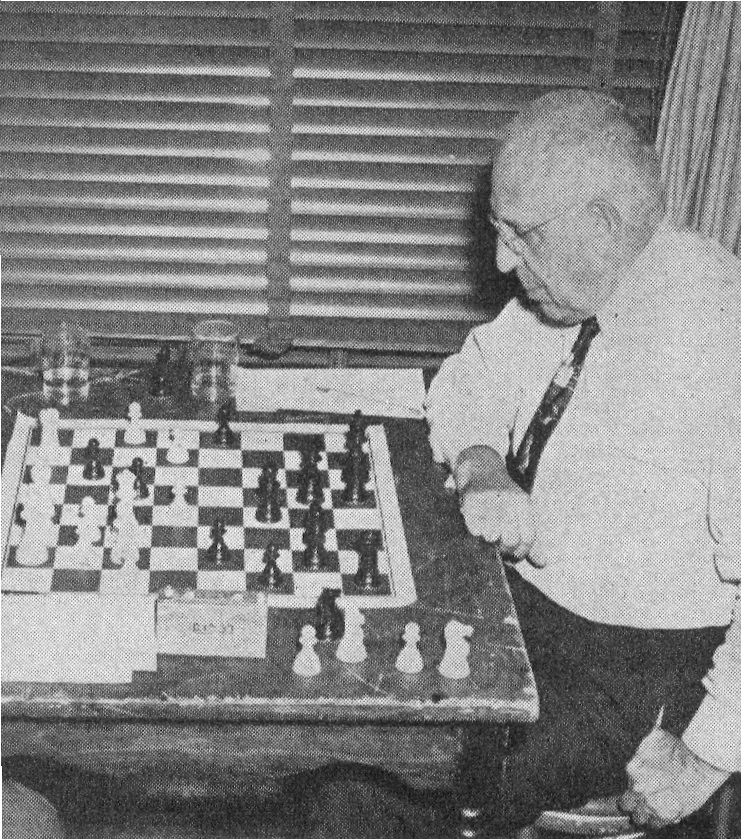

A photograph of Whitaker given on page 326 of A Chess Omnibus:

John Hilbert has sent us a database of over 40 games which he has traced since the publication in 2000 of his book Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chessmaster.

Two specimens:

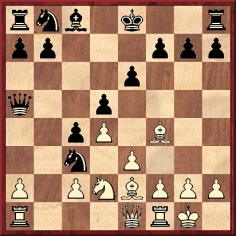

Morton Eschner – Norman Tweed Whitaker

First match-game, Philadelphia, 1910

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 c3 Nxe4 7 Re1 Nc5 8 Bxc6 dxc6 9 Nxe5 O-O 10 d4 Ne6 11 Nd2 c5 12 Ndf3 cxd4 13 Nxd4 Nxd4 14 cxd4 Be6 15 f4 Qd5 16 Be3 Rad8 17 Rc1 c6 18 a3 Bd6 19 Qc2 f6 20 Nf3 Rfe8 21 Qf2 Bb8 22 Rc5 Qd7 23 Rh5 Ba7 24 Qh4 g6 25 Rh6 Bd5

26 f5 Bxf3 27 fxg6 Bxd4 28 Rxh7 Bxe3+ 29 Rxe3 Qd1+ 30 Kf2 Rd2+ 31 Kg3 Rxg2+ 32 Kf4 Rg4+ 33 Qxg4 Qd4+ 34 White resigns.

Source, Philadelphia Item, 22 May 1910.

P. Driver – Norman Tweed Whitaker

Mercantile Library Chess Association Championship, Philadelphia,

1911

Queen’s Pawn Opening

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 c5 3 e3 e6 4 c4 Nc6 5 Nc3 Nf6 6 Bd2 dxc4 7 Bxc4 a6 8 O-O b5 9 Bb3 c4 10 Bc2 Bb7 11 e4 Be7 12 Bg5 O-O 13 e5 Nd5 14 Bxe7 Qxe7 15 Ne4 Ncb4 16 Nd6 Nxc2 17 Qxc2 Bc6 18 a3 f6 19 Rfe1 fxe5 20 dxe5 Nf4 21 Ne4 Qf7 22 Re3 Qg6 23 Ne1

23...Bxe4 24 White resigns.

Sources: Philadelphia Public Ledger, 23 April 1911 (courtesy of Neil Brennen) and the Staten Islander, 17 May 1911.

(11931)

Addition on 29 January 2024:

Below is the chess report in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 24 October 1918, page 18:

‘N.T. Harrison’ was, if we may coin a neologism, the nom de non guerre of N.T. Whitaker.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.