Edward Winter

The text of C.N. 821, published in the September-October 1984 issue of C.N.:

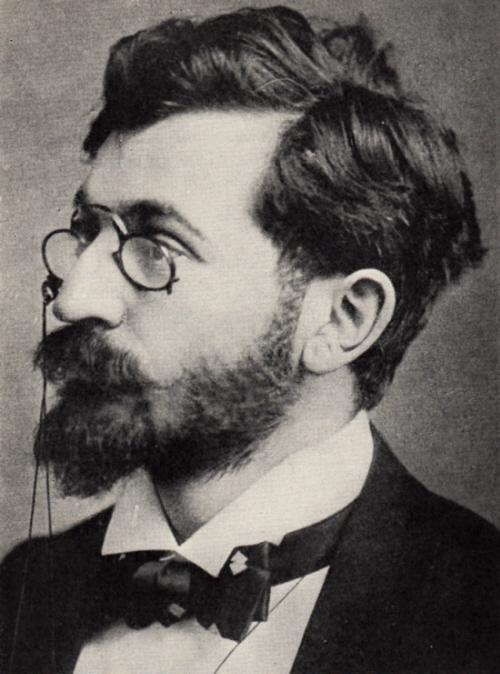

We record with great regret the death of W.H. Cozens, the author of many fine games collections and a most distinguished contributor of book reviews and occasional articles to the BCM. We have never known a chess writer with a greater feel for the euphony of the English language. On a personal level we have many reasons to remember W.H.C. with deep gratitude. For World Chess Champions not only did he write the ‘Early Times’ chapter but he most kindly read the entire manuscript, making numerous suggestions and corrections. Last year he proof-read the Amos Burn book in record time. He was the first subscriber this magazine ever had and was one of its staunchest supporters.

Over many years we had a most pleasant correspondence with him. ‘I don’t regard myself as a professional writer’, he once told us, ‘just a retired old fogey who sometimes writes about things that interest him’. On another occasion we requested an autobiographical note (for World Chess Champions), the reply being, ‘I have no pretensions to scholarship, nor even to taste. My life has been rich with many interests, of which chess is just one. My chess library has given me great pleasure but I recently sold 300 chess books to make room for other items. Mathematics, art, music, poetry, botany, philology ... all jostle with chess, and I would no more buy a chess book with the object of making myself a chessplayer than I would buy the poetical works of Shelley to make myself a poet. Call me a chess lover. That sums it up.’

In his last letter, earlier this year, W.H.C. told us he was making a collection of the games of Jacques Mieses. ‘Whether I shall ever do anything with it I doubt: Time’s winged chariot ...’

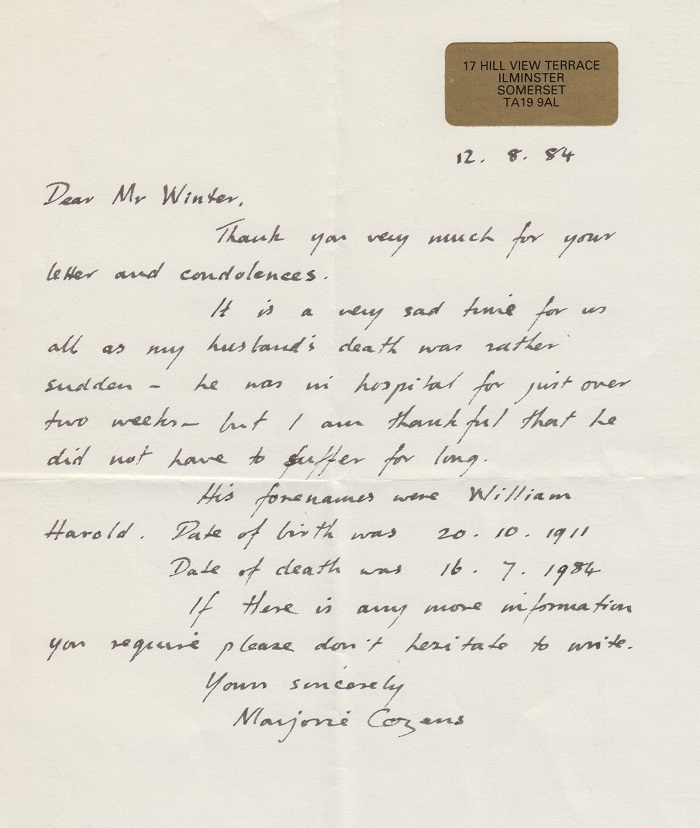

From information received from his widow we are able to place the following details on record: William Harold Cozens, born 20 October 1911, died 16 July 1984.

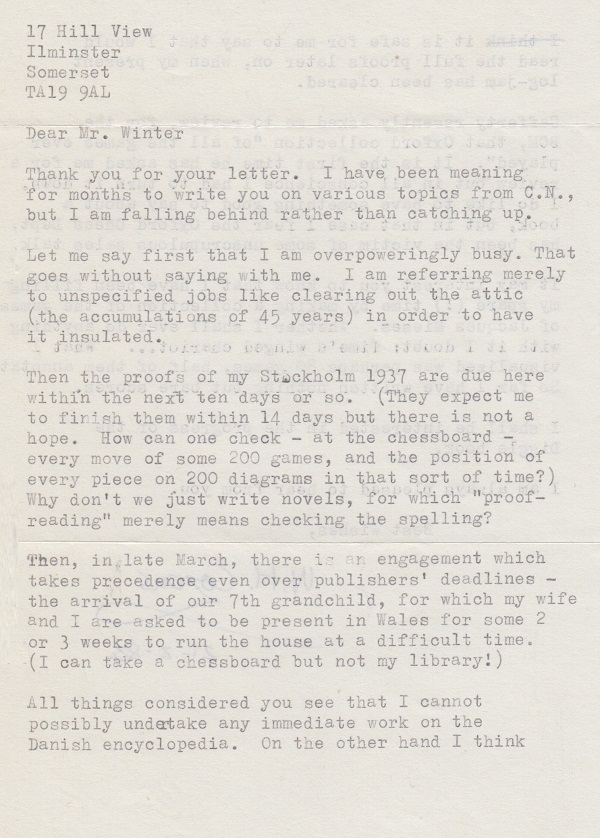

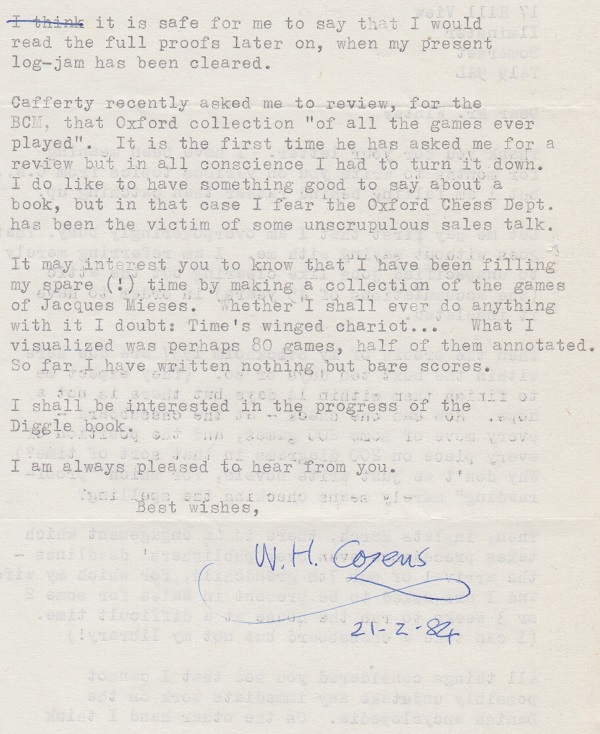

Below is W.H. Cozens’ last letter to us (21 February 1984), as well as one of two letters that we received from his widow, Marjorie:

From Gordon Pollard (Wallingford, England):

‘A friend in Somerset has sent me a cutting from the local newspaper containing a letter from one of Cozens’ former pupils:

“When I first knew him he was, I suppose, barely 20 years of age yet he seemed to me so wise, mature and understanding. He taught me the beginnings of Latin and chess, but much more that does not appear on a school curriculum ...”

That was written after a break of 40 years – a splendid tribute to W.H.C.’s beneficial and far-reaching influence.’

(855)

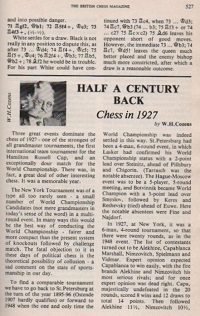

BCM, November 1977, page 527

W.H. Cozens’ tremendous set-piece articles ‘Half a Century Back’ began in the BCM in 1958 and ran for over two decades. However, on 10 December 1981 he informed us:

‘Half a Century Back will not be appearing any more. When I submitted the 1981 (i.e. 1931) script Cafferty said he had no room for the next six months unless I would permit him to cut it by 50%. Well, I know the editor is entitled to his blue pencil, but not even the newest new broom can be allowed to cut an article to ribbons. I politely suggested that he return it to me; I shall not be troubling the BCM again.’

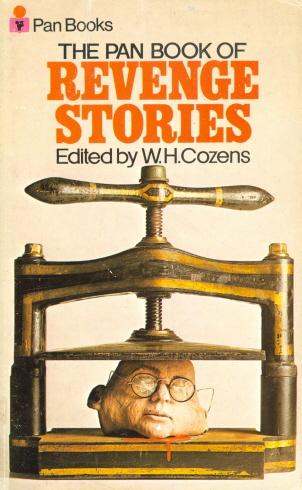

Cozens’ love of good writing was demonstrated by an anthology he edited in 1971, The Pan Book of Revenge Stories:

(3183)

Cozens’ longest contribution to the BCM was an interview with Brian Reilly on pages 352-369 of the August 1981 issue. Page 354 was given over to drawing of Reilly by him.

C.N. 2219 raised the subject of the best and worst book reviewers, and we observed:

A frontrunner in the former category is surely W.H. Cozens, whose critiques graced the BCM for decades.

From C.N. 3766, regarding James M. Aitken and G.H. Diggle:

When commenting in C.N. 3606 that Brian Reilly was perhaps the best of all the BCM editors, we had in mind not just his own writing but his skill in assembling, and maintaining over the decades, some outstanding contributors. There were, for instance, frequent book reviews by not only J.M. Aitken but also W.H. Cozens, W. Heidenfeld, D.J. Morgan and, indeed, G.H. Diggle himself.

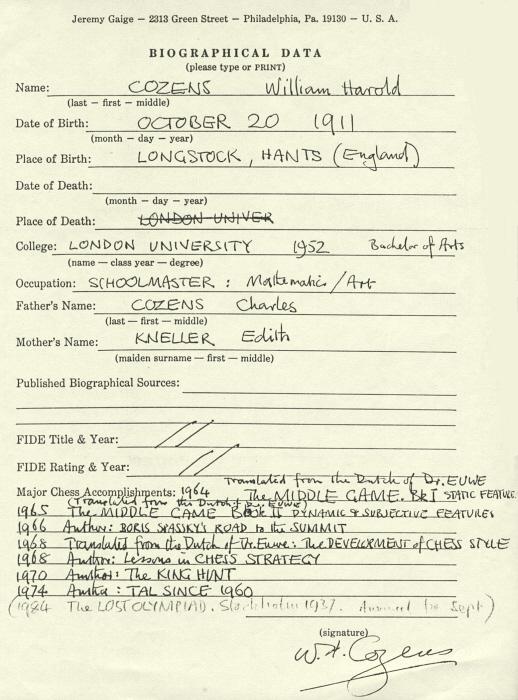

Jeremy Gaige gathered much data with a biographical form circulated to chess personalia. By way of example, below is the sheet completed by W.H. Cozens:

The information about his parents has taken us to the remarkable Cozensweb site, which gives many further details.

(6998)

‘It’s a great book without a doubt, and can go straight on the shelf alongside Alekhine and Tarrasch and fear no comparisons.’ That was the opinion of W.H. Cozens in a review (December 1969 BCM, pages 370-371) of Bobby Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games, published by Simon & Schuster in the United States and by Faber and Faber in the United Kingdom.

See Fischer’s Fury, of which the above is the opening passage.

On page 60 of Tal Since 1960 (St Leonards on Sea, 1974) W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘... when I remarked to Dr Euwe after the publication of his book From My Games in 1938 that the book would have been even better for the inclusion of a short selection of “Other Games” such as gave such a sparkle to the Alekhine books he said, “I have no ‘other games’”. Botvinnik has a similarly austere attitude.’

Euwe’s reply is not to be taken literally, and we wonder whether readers can submit any little-known sparklers from old publications.

(4510)

The above woodcut of Emanuel Lasker, by Erwin Voellmy, was published on page 65 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, May 1924. It is similar to an illustration by W.H. Cozens on page 143 of the May 1959 BCM:

Another picture of Lasker by Cozens appeared on page 323 of the November 1964 BCM:

(5059)

From page 81 of the earliest editions of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander:

(8644)

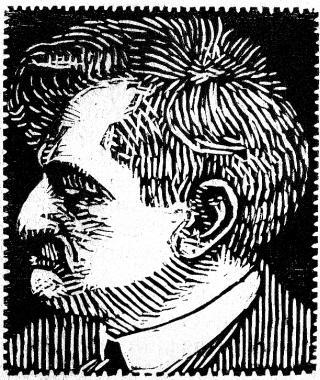

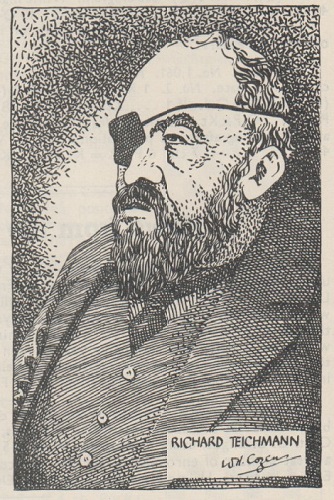

An illustration by W.H. Cozens on page 316 of the November 1961 BCM:

(8922)

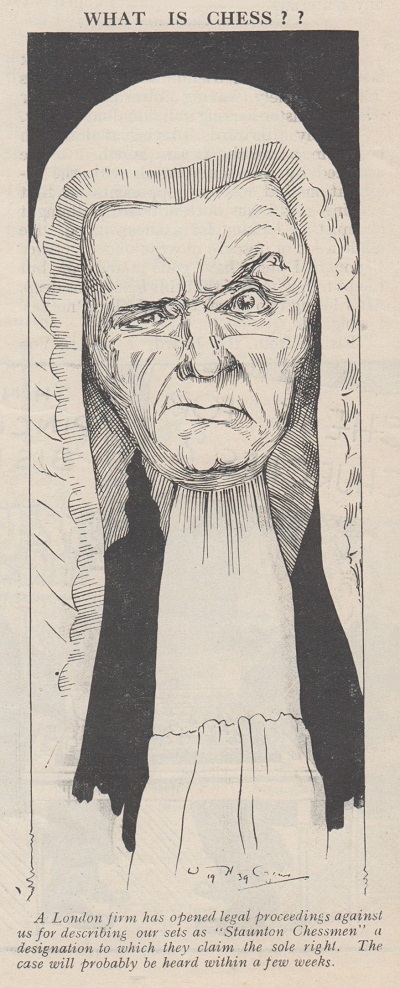

Sketch by W.H. Cozens, CHESS, 14 April 1939, page 278

See Chess and the Courts.

A light game played during the Second World War by that excellent writer W.H. Cozens:

C.E.Y. – William Harold Cozens

Kent, 1942

King’s Pawn Opening

1 e4 e5 2 d3 Nf6 3 Nf3 Bc5 4 Nxe5 Nc6 5 d4 Bxd4 6 Nxc6 dxc6 7 Bc4 Bxf2+ 8 Kxf2 Nxe4+ 9 Ke1 Qh4+ 10 g3 Nxg3 11 Bxf7+ Kxf7 12 Qf3+ Nf5+ 13 Kf1 Qc4+ 14 Qd3 Be6 15 Nd2

15...Ne3+ 16 Ke2 Bg4+ 17 Kxe3 Rae8+ 18 Ne4 Rxe4+ 19 Qxe4 Qe2+ 20 Kf4 g5+ 21 Ke5 Re8+ 22 Kd4 and Black announced mate in three.

Source: BCM, June 1942, pages 128-129.

(Kingpin, 2001)

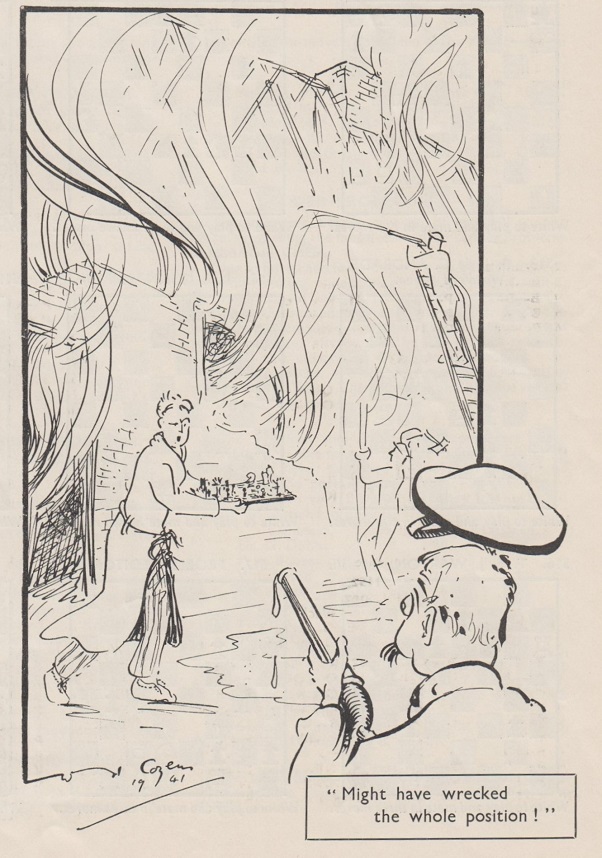

A favourite theme of chess cartoons is the game’s imagined paramountcy.

Firemen were featured in C.N.s 8927, 8943 and 9007, and below is a drawing by W.H. Cozens from page 77 of the February 1941 CHESS:

(10427)

From page 67 of CHESS, February 1941, in a tribute to Emanuel Lasker by W.H. Cozens:

The highlighted remark attributed to Kmoch deserves further scrutiny:

‘Just as some players sacrifice pawns for an attack, so Lasker frequently sacrifices time and space to keep the game alive.’

(10426)

See also C.N. 10434.

When contributing some items to D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column on page 40 of the February 1957 BCM, W.H. Cozens observed:

‘... even busy people should try to co-operate in the sharing of good things.’

Over the decades, such a spirit of generosity on the part of readers has resulted in innumerable contributions to C.N. (including material from Cozens himself, up to his death in 1984). Tim Harding, though, thinks otherwise. In a set of typically peculiar assertions on page 292 of his book British Chess Literature to 1914 (Jefferson, 2018) Harding wrote:

‘He [E.W.] also benefits from a network of contributors worldwide, happy to do so [sic] in exchange for having their books promoted or just “seeing their name up in lights”.’

(10815)

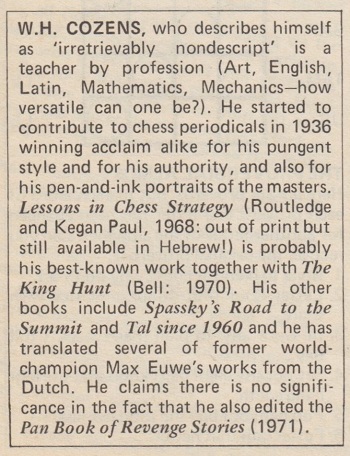

In the 1970s some fine chess writing appeared in the British magazine Games & Puzzles. A note about the chess editor, the ‘irretrievably nondescript’ W.H. Cozens, was on page 12 of the August 1975 edition:

The monthly chess column, several pages long and intended for inexperienced players, included notable guest contributors.

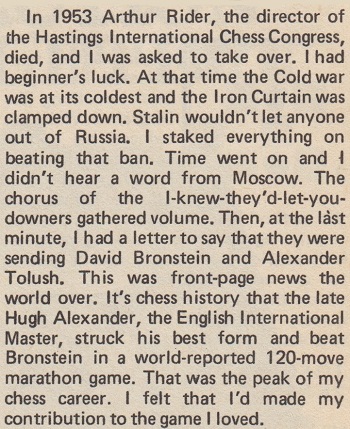

Page 21 of the September 1975 issue had an article by Frank Rhoden, ‘Pawns and People’, which serves as a reminder of the chess world’s debt to organizers:

In fact, Rider died on 24 January 1954 (C.N. 9107), but the Hastings, 1953-54 tournament was indeed run by Rhoden. See Chess and Politics (The Bordell Case).

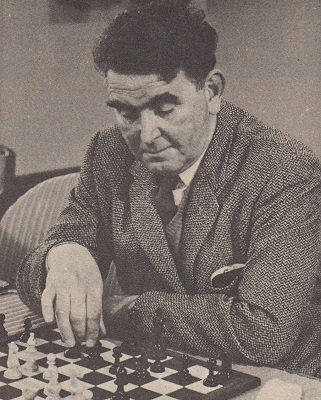

Frank Rhoden (accompanying photograph in Games & Puzzles)

Some interesting points were made by Michael Basman at the start of an article, ‘Modern Methods’, on page 30 of the February 1977 issue:

From the following page:

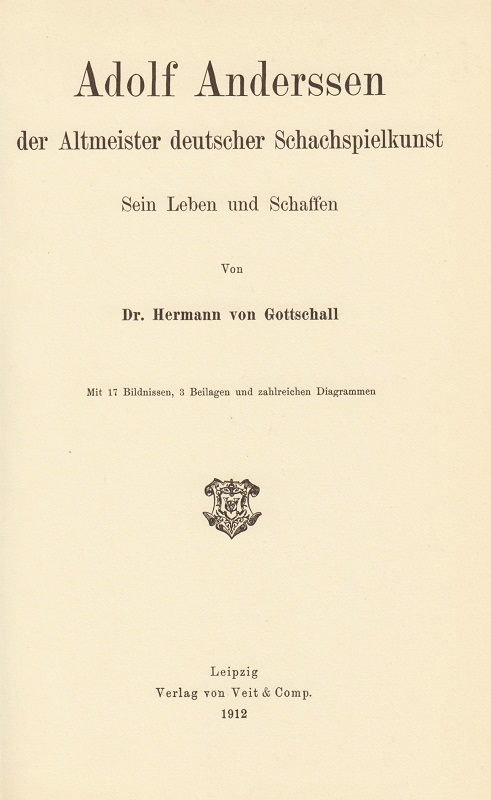

On page 28 of the December 1976 issue of Games & Puzzles W.H. Cozens chose his favourite chess book, via a reference to a long-running BBC radio programme:

‘If ever Roy Plomley offers you the chance to take any one book along with your Desert Island Discs, take [Hermann von Gottschall’s] Adolf Anderssen. Sein Leben und Schaffen (long out of print, of course). It will thrill you for the rest of your life.’

(11644)

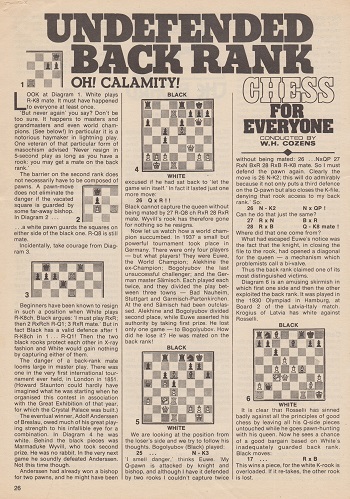

The first page (26) of W.H. Cozens’ ‘Chess for Everyone’ column in Games & Puzzles, September 1976:

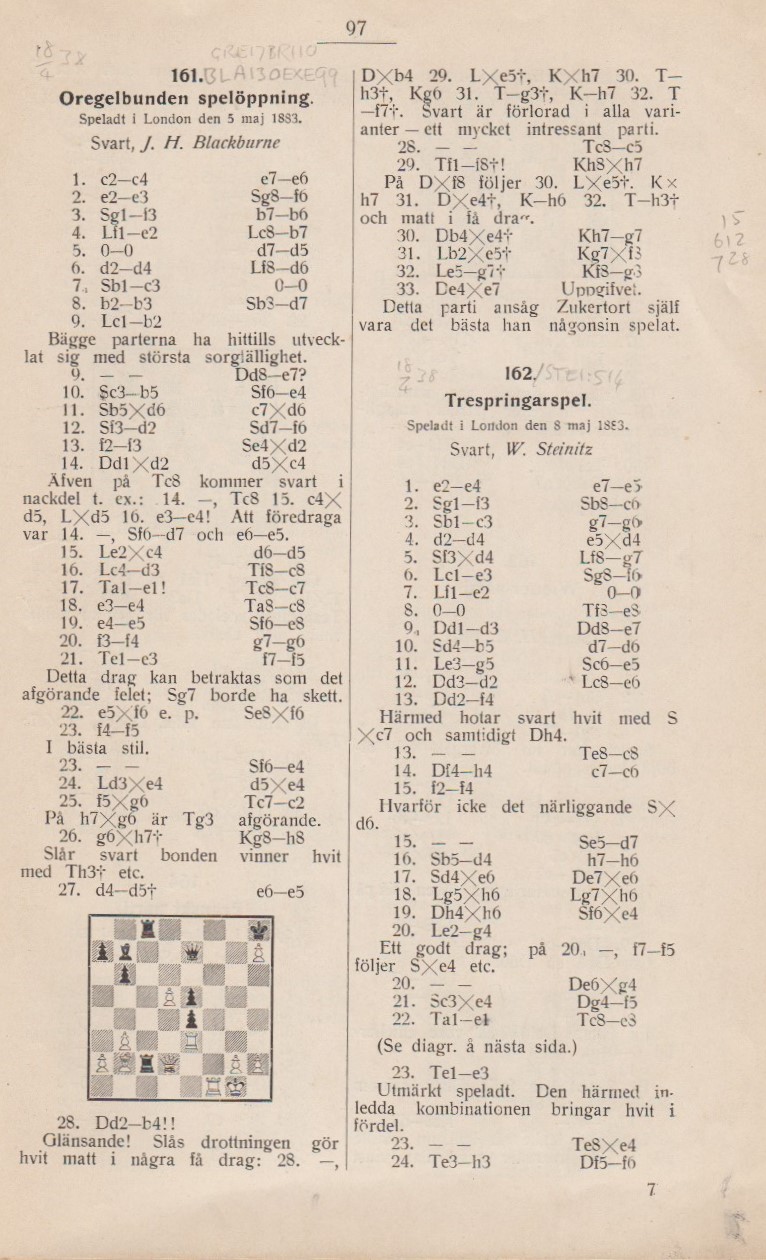

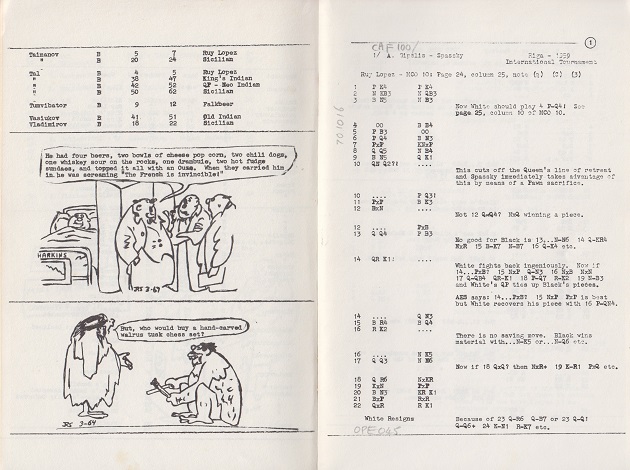

J.H. Zukertort by A. Olson (Stockholm, 1912), page 97:

The pencil notes are by the book’s previous owner, W.H. Cozens.

See Zukertort v Blackburne, London, 1883.

An extract from an article about the knight by W.H. Cozens on pages 22-25 of Games & Puzzles, January 1976:

‘It is curious that the writers of so many beginners’ books find difficulty in defining the knight’s move. “One along and one diagonally” and “Two up and one across” are two nonsensical efforts ...

The easiest definition of the knight move is: on a block of squares 3 x 2 a knight jumps from one corner to the diagonally opposite corner.’

From page 27 of Games & Puzzles, July 1976:

The poet’s name was given as M.M. Parrish on page 71 of the Saturday Evening Post, 24 November 1951:

There follows a selection of contributions to C.N. by W.H. Cozens:

Regarding Morphy v the Duke and Count:

A point on which sources vary is the opera that was being performed, i.e. whether it was The Barber of Seville or Norma. This question was raised in C.N. 120, and in C.N. 159 W.H. Cozens responded: ‘Who cares? When Michelangelo was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, who cares what chant was heard from below?’ Even so, it is a matter which has interested other chess writers (e.g. D.J. Morgan on page 362 of the November 1954 BCM and C.J.S. Purdy on page 276 of the December 1955 Chess World).

Given that it is still proving impossible to establish the exact date on which the Morphy brilliancy was played, attempts to identify the opera performance in question remain worthwhile, if only for that reason.

Even J.H. Blackburne has been suggested as a possible precursor of hypermodern play. From page 207 of The Game of Chess by Harry Golombek (various editions):

‘His games, though so strongly influenced by Morphy, also curiously foreshadow the most modern developments. For example, as early [as] in 1883 at the great international tournament in London he was playing as Black the first three moves of Nimzowitsch’s Defence to the Queen’s Pawn, three years before the birth of Nimzowitsch; whilst his English opening at Ostend, 1907 was remarkably similar for some 12 moves to the system evolved many years later by Réti.’

That claim was mentioned in C.N. 283, and in C.N. 411 W.H. Cozens gave his view on whether Blackburne’s games showed evidence of a system:

‘No, not at all. He was the most faithful exponent of the open game right to the last. Even in his last tournament (St Petersburg, 1914) he played 1 e4 most of the time. We tend to forget his sense of humour. When he sat down opposite Nimzowitsch one can almost see the twinkle in his eye as he opened 1 e3 d6 2 f4, etc. (and won). If anyone tried to be funny with him he played along. Gunsberg v Blackburne went 1 e3 g6, followed by ...Bg7, ...d6, ...e6, ...Ne7, ...O-O. Late in life, like other aged masters, he did not trust his own opening erudition against the youngsters (e.g. he met Marshall’s Q-Pawn with ...Nf6, ...c6, ...d6, ...Qc7). But to see a hypermodern system in all this is reading into it more than is there.’

On page 260 of Chess Explorations we added that the Blackburne games from Ostend, 1907 which Golombek appeared to have in mind were against E. Znosko-Borovsky, W. John and E. Cohn.

(411)

See Hypermodern Chess.

W.H. Cozens writes:

‘From the Chess Memoirs of Dr Platz (Coraopolis, 1979), page 51:

“I was present when Reuben Fine asked him (A. Rothman) ‘Is it true that you know the columns of MCO by heart?’ And he answered: ‘Yes, it is true.’”

Some of today’s young hopefuls with similar ambitions might do well to reflect that the end product of this astonishing feat was not a Karpov or a Capablanca, but ... A. Rothman.’

(413)

For further information about Rothman, see C.N.s 4930, 7350 and 7357.

Our feature article on this topic is Memory Feats of Chess Masters.

W.H. Cozens writes:

‘The verb to sac is with us; the participle sacing still gives one a jolt.’

(415)

See Chess and the English Language.

In a discussion about private book collections, following a suggestion (C.N. 102) attributed to Dale Brandreth that there were no more than 1,200 people worldwide who could be termed serious collectors (i.e. those possessing more than 100 tournament books), W.H. Cozens wrote in C.N. 468:

‘A “serious collector” is defined as one who possesses more than 100 tournament books. What a very arbitrary criterion. I suppose I just about squeeze into that category, but if I had to part with those 100 tournament books, I should not be terribly grieved. I should, however, be very upset if I lost my 250 individual game anthologies, or my 40-or-so of that rarer species, the one-nation anthology; or my 400 bound volumes of chess magazines ...

Most of my friends are not chess addicts and when any of them visits me in my library, I realize guiltily how lopsided it has become. To allow one subject – and such a trivial one as chess – to run to over 1,000 volumes, and to spread into over 20 languages, is cause not for pride but for a sense of shame.’

A view expressed by W.H. Cozens on page 161 of the April 1976 BCM:

‘The obsession with grading is fast becoming the curse of chess; from the top (where the multiplication of grandmasters already calls for the creation of a new supermaster class – the dozen or so with legitimate pretensions to a world title match) right down to club level where it is simply laughable.’

(2010)

See Chess Ratings and Chess Grandmasters.

The text of C.N. 71 (‘The leisurely fianchetto’):

What is the longest gap in master play between a g- or b- pawn being advanced and the subsequent placing of a bishop on one of the ‘knight two’ squares?

In C.N. 98 W.H. Cozens remarked on the comparative merits of the descriptive and algebraic notations in such an instance:

1. (Descriptive): What is the longest gap in master play between P-Kt3 and the subsequent B-Kt2?

2. (Algebraic): What is the longest gap in master play between the playing of b3, b6, g3 or g6 and the subsequent Bb2, Bb7, Bg2 or Bg7, as the case may be?

Mr Cozens concluded:

‘Algebraic, for some purposes, can be downright silly.’

(9650)

See The Chess Fianchetto.

W.H. Cozens brings to our attention this game:

Fiorito – Groiss

Holland v Austria correspondence, circa 1981 or 1982

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bg5 e6 7 f4 Qb6 8 Qd2 Qxb2 9 Nb3 Qa3 10 Bxf6 gxf6 11 Be2 Nc6 12 O-O Bd7 13 Bh5 Bg7 14 Rad1 O-O 15 Rf3 Rad8 16 f5 Ne7 17 Nb1 Qxa2 18 Qxd6 Nc6 19 Nc3 Qxc2

20 Na1 Resigns (owing to 20...Qb2 21 Rb1).

Has any other game ever finished with the move Na1?

(410)

See C.N. 9127.

Even specimens of a mate in one being overlooked are less scarce than might be thought. In C.N. 414 W.H. Cozens pointed out a number of master games (the italics indicate the overlooker):

See Missed Mates.

From W.H. Cozens, on the topic of the best chess magazines:

‘As far as English language is concerned the BCM has no rival, but it is not without its faults, chief among which is a tendency to over-annotation. Some of Nunn’s annotations can hardly be followed without three boards on the go. I also regret the lack of considered reviews and the gradual phasing out of the literary flavour in favour of unrelieved technique.

Of the various eccentricities of the magazine CHESS the most amusing is the fiction that it is a fortnightly. For 19 years CHESS was published in large format – about 25cm x 18cm. Its 20th year began with the reduction to its present page size – about 21cm x 14cm – and at the same time it became a fortnightly. Some 18 months later the ominous double numbers began, and since then, for a quarter of a century, CHESS has been a fortnightly which appears once a month (at most!) bearing two numbers on each issue.

As for the best chess magazine world-wide, if anyone knows of a better one than Europe Echecs I should be glad to hear of it.’

(416)

W.H.Cozens reacts to our words ‘just in time to keep the game a miniature’ regarding a game in which Black resigned at move 25:

‘What is the precedent for calling a game of 25 moves (or fewer) a miniature? I have seen the name used in various senses. The Dictionnaire des Echecs, for instance, says, unequivocally, “A short game, lasting 20 moves or fewer”. Who can (or needs to) lay down the law on such matters? A miniature is a short game. I leave it at that.

In the problem world, of course, the usage has a definite meaning – not more than seven pieces – though who laid this down, and when, I don’t know. I have assumed that the convention dates from Blumenthal’s Schachminiaturen (1902) but perhaps some problem specialist will put me right on that. Wallis’ 777 “Miniatures in Three” says “... it is pretty well laid down ...” The four authors of The Chess Problem, that authoritative tome of 1887, do not seem to use the word. (Such an idea, anyway, would have been repulsive to any one of them, I suspect!)’

(471)

With regard to our ‘miniature’ remark, see C.N. 282 on pages 33-34 of Chess Explorations, as well as Queen Sacrifices.

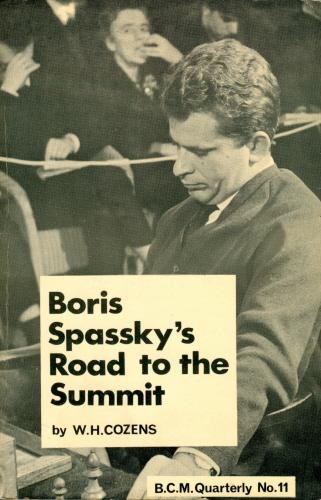

In correspondence with W.H. Cozens in the 1970s we criticized a book(let) by James Schroeder, and (as reported in C.N. 2640) on 29 January 1975 Cozens replied:

‘I was amused (and, uncharitably, rather pleased) at all you had to say about Mr James Schroeder. Soon after the publication of my Spassky’s Road to the Summit in 1966 the BCM sent me a copy of a really vicious review of it, by our Mr Schroeder. We were amused and also puzzled by it, until we discovered the reason: he was himself about to bring out a book of Spassky’s games and he resented us getting in ahead of him. When his book appeared (I forget the exact title) the BCM sportingly asked me to review it and I thought “the Lord hath delivered him into my hand”. But when I saw the book it was so laughable that I refused to review it. To do so would have been a waste of BCM space and readers’ time. If you have found a book worse than that one it must really be something.’

We own Cozens’ copy of Schroeder’s volume, Boris Spassky World’s Greatest Chess Player (Cleveland, 1967):

Does a reader have Schroeder’s review of Spassky’s Road to the Summit?

James Schroeder’s output was criticized in C.N.s 129 and 154.

(10967)

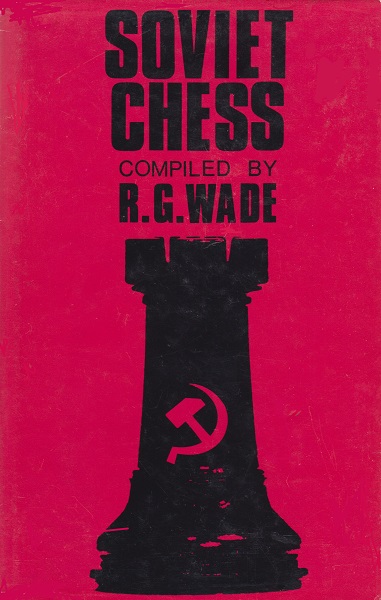

Below is one of several barbs by Ed Edmondson when reviewing R.G. Wade’s Soviet Chess (London, 1968) on page 108 of Chess Life, March 1969:

‘Not recommended if your budget for chess books is at all limited. It’s one man’s opinion, but I consider this volume to be only for those who can truly afford to satisfy their own curiosity about its dullness or to acquire a collection of chess books regardless of quality.’

Another man’s opinion was on pages 58-59 of the February 1969 BCM, where one of the greatest of all chess book reviewers, W.H. Cozens, expressed some criticism of Soviet Chess but also praised it highly, concluding:

‘It would be hard to suggest how any serious student of chess could find a better use for two guineas.’

(11208)

C.N. 11208 described W.H. Cozens as ‘one of the greatest of all chess book reviewers’, and, by way of example, a glimpse is given here of his contribution on pages 204-205 of the May 1973 BCM, where he examined Attack and Defence in Modern Chess Tactics by Pachman and Schönheit der Kombination by Golz and Keres.

‘Here are two books concerned with the real meat of chess – the middle game’, he began, and then briefly traced the background of each work, including the following:

‘But the reader will be wanting to know how much is Golz and how much Keres. The answer is that about 90% is Kurt Richter! He died three years ago but the style remains unmistakable; his fans (who are many and by no means confined to Germany) will be delighted to have this last unexpected collection of his work. Golz has lovingly put together a mass of material and arranged it in a loose sequence to form a highly un-systematic course in chess tactics. Keres’ contribution is a 12-page appreciative essay on Richter – his specialities in the openings, his achievements over the board and his style of annotation.’

Cozens then compared Pachman and Richter:

‘Pachman is a pedagogue – one of the greatest: he understands chess. Richter is an enthusiast: he loves chess. Pachman marshals his material and teaches us point by point. Richter merely revels in it. He rambles: one thing reminds him of another and then another, each more remarkable than the one before.’

And, from the next paragraph:

‘In short, Pachman is primarily a teacher who, like all good teachers, is sometimes entertaining; whereas Richter is essentially an entertainer who, almost incidentally, contrives to be very instructive.’

After further information about the books’ content and layout, Cozens concluded:

‘If the present reviewer has given the impression that he prefers Richter he pleads guilty: but hastens to add that the choice must be a very personal one, depending on why you play chess anyway. Because you are good at it? Because you want to be better at it? Or just because you are hopelessly in love with it?’

(12051)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.