Edward Winter

Our article Over and Out referred to ‘a clear-cut lie’ by Eric Schiller and to his ‘mendacity’. The ink was hardly dry before we had occasion to note more of the same, in the form of a grotesque attack on us at his Chesscity website which was flatly untrue, not to say libellous.

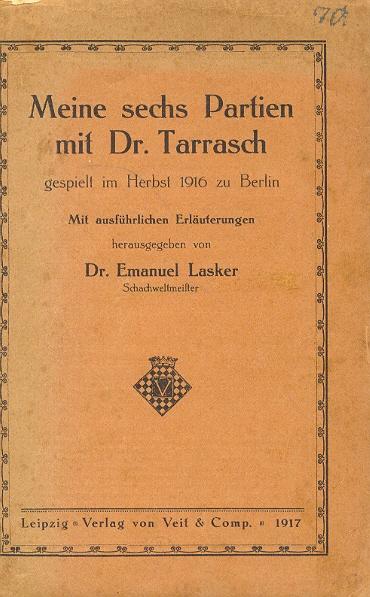

As is well known, Lasker and Tarrasch played two matches, in 1908 and 1916. The first of these was for the world championship, but the second (six games only) was not. Even so, some authors have erroneously indicated that the 1916 encounter was a world title match, two examples being Karpov in Miniatures from the World Champions (Batsford, 1985, pages 43-44) and Koltanowski in With the Chess Masters (Falcon Publishers, 1972, page 48).

Koltanowski wrote: ‘Twice Tarrasch mounted a campaign to take the world title from Lasker – and twice Lasker beat him badly.’

We quoted this in the September-October 1986 issue of Chess Notes and simply added a five-word rhetorical question, ‘When was the second time?’ The item was included on page 160 of our 1996 book Chess Explorations.

A straightforward matter, it might be thought, but now enter Eric Schiller. In late 1999 he posted on his website the following monstrosity:

‘Young Mr Winter gives as an “example of general carelessness” that Koltanowski makes the absurd statement that Tarrasch played two matches with Lasker, as only one was played. Anyone who has followed the careers of these great players knows that there were, of course, two matches. The second match does contain some rather poor play by Tarrasch, who got clobbered, but nevertheless it was a real match. The games are presented below. In his 90s Kolty may slip up from time to time. But the insult by the impudent young chess historian is without foundation. In any case, Kolty’s witty prose and wealth of anecdotes are far more valuable than some whining lad who can’t even get the facts right.’

On another page on the same site Schiller wrote, under the heading ‘Chess Explorations and Exploitations’:

‘So when Young Salieri (not his real name, but many will recognize the moniker) claimed that he knows more about the early days of the century, when George was actually playing and eye-witnessing events, it behooved us to check the facts. The question is simple: did Lasker play one match against Tarrasch (as claimed by Young Salieri), or two, as Kolty stated. Click here for the answer.’

In short, although we had been referring to the status of the 1916 match, i.e. the (indisputable) fact that it was not for the world title, Schiller falsely and aggressively proclaimed that we were unaware of the very existence of the match.

On 14 December 1999 we sent an e-mail message to the Chesscity site asking for a retraction and apology. To quote just one paragraph from our message:

‘To claim that I am unaware of the 1916 match is absurd, if only because on page 214 of my book [Chess Explorations] I specifically referred to it. Or again, the book that I edited for Pergamon Press, World Chess Champions, included some discussion of the 1916 match, together with the annotated score of one of the games.’

Apprised of the truth, Schiller had no intention of apologizing. On 18 December he wrote to us:

‘Nio [sic] apology necessary, you are guilty of an unwarrented [sic] attack on Koltanowski. I will defend him against your garbage.’

The same day he rewrote bits of his website, maintaining the untruth that we had claimed there had been only one Lasker v Tarrasch match, intensifying his personal attack on us and introducing a fresh charge, equally groundless: now, he added, we were also guilty of ‘sloppiness, poor editing’. To be accused of that by Schiller, of all people, is priceless.

It may be recalled that our ‘Over and Out’ article mentioned that Schiller’s books contain ‘hundreds of gross errors’, and we have often quoted chapter and verse. See, for example, the 1999 Kingpin, in which we cited a selection of nearly 40 such instances from three books published by Schiller in 1999 alone. In our book Kings, Commoners and Knaves we pointed out dozens of historical and other blunders in his book World Champion Combinations (in which, for example, the chapter on Capablanca has six games and four positions, with obvious factual gaffes in every single one of them).

Our ‘Over and Out’ article also commented on how some writers who are criticized ‘ignore the (unanswerable) facts and pin their hopes on a water-muddying counterattack’, and that is precisely what Schiller has been doing in the present case. He has brushed aside the inconvenient matter of his hundreds of gross errors, trying instead to retaliate via another issue of his own choice, Lasker v Tarrasch. But what do we find? His attempted revenge is based on a distortion of the facts which is brazen even by his own dire standards. And when it blows up in his face, he refuses to correct the record properly or apologize, preferring to launch fresh attacks, also false. Despicable? Of course. Surprising? Not at all. It is vintage Eric Schiller.

***

Our above-mentioned feature article on Koltanowski observed: What Schiller lacks in intelligence he makes up for in guile.

Afterword: The above statement was first published in 1999 at the Inside Chess website, as announced in C.N. 2362 under the title ‘Preposterous’:

Over the years we have been the subject of some preposterous attacks, but few compare with the one posted by Eric Schiller at his Chesscity website in late 1999. Rather than correcting any of his hundreds of gross factual errors, he launched a personal rant against us which was untrue as a plain matter of historical record. Since he refused to apologize or correct his falsehoods, we have issued a detailed statement on the website of Inside Chess (www.insidechess.com).

Regarding the Lasker/Tarrasch matter, another citation is offered to demonstrate that we were perfectly aware of their 1916 match. Following comments by Raymond Keene on page 346 of the August 1985 BCM, we wrote on page 392 of the September 1985 issue:

So we now have a new category of world championship matches comprising any unofficial encounter which Mr Keene thinks the loser might have had at least an outside chance of winning. Having invented this novel criterion, will he start claiming that the 1916 Lasker-Tarrasch match was also for the world title?

C.N. 3951 showed that, for his part, Koltanowski repeated his mistake when writing about Tarrasch on pages 2-3 of Chess Digest Magazine, March 1969:

‘Dr Emanuel Lasker was his stumbling block – he played two matches for the world title with Lasker and lost both badly.’

Below is the text of our Kingpin article referred to in the Inside Chess website.

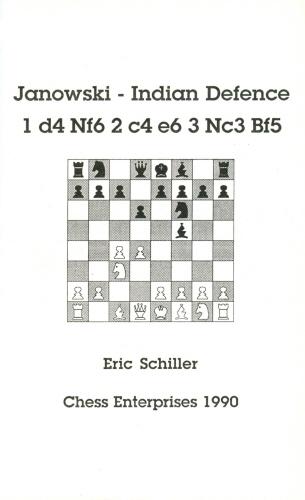

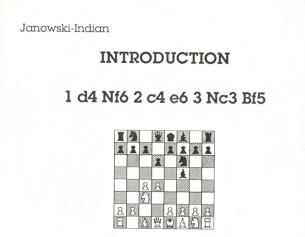

It would be foolhardy to estimate how many books the ugsome Eric Schiller has written in 1999, but below are some observations on three of them, all from Cardoza Publishing:

The first is entitled Whiz Kids Teach Chess and contains many infantile errors. For instance: ‘… Black didn’t advance the e-pawn to d5’ (page 24), and ‘When Black advances the d pawn two squares to d6 …’ (page 103). On page 35 we read ‘The armies are at equal strength’, but this refers to a position in which Black is a rook ahead. On page 109 ‘checkmate’ is illustrated by two illegal positions (in the first of which White has no king and in the second of which Black has two).

The young reader is also given a little politics. On pages 138 and 140 Schiller goes awry with the French for FIDE, whereas on page 115 he inexplicably refers to ‘the Professional Chess Association (WBCA)’.

The book’s prose would be shameful from a 12-year-old, and even the proper use of apostrophes is beyond Schiller. Examples: ‘a normal part of most top young player’s days’ (page 23) and ‘Beginner’s are usually advised to never resign’ (page 121).

One final irresistible quote is the typically slipshod reference on page 94: ‘… as Gabe relates (on page whatever)’.

Then there is the Encyclopedia of Chess Wisdom, another showcase for Schiller’s slapdashery, as the following examples show:

Wrong moves: On page 59, after 1 e4 e5 2 f4, Black’s move is given as …Be5, twice. Page 301 has the illegal move Qh4+ instead of Qh6+. The same page claims that in a simple queen ending 3 Qc1 is mate, but it is not. Page 279 has …Qa1 checkmate instead of …Qh1.

Wrong history: Page 69 attributes a quote to Tarrasch in 1935, by which time he was already dead. Page 167 claims that in 1895 Lasker was ‘on his way to the World Championship’, but he had won it in 1894.

Inscrutable reasoning: Page 82 starts: ‘White offered the initial gambit, but it is Black who holds the extra pawn.’ This refers to a position where White is a pawn ahead.

Illiteracy: ‘it is still you’re turn to move’ (page 142). Another example: ‘A passed pawn increases it’s strength …’ (page 250 – in large letters and framed).

Bizarre typos: ‘There are of course slow ways of chasing denied away …’ (page 131). From the context, it would seem that ‘chasing the knight away’ was meant. Another example comes on page 145: ‘it can also crate threats’. With all Schiller’s typos, one could pass denied away crating lists.

Misspelling of names: ‘Lake Hopatong’ (page 160). ‘Wywill’ (page 297).

Wrong diagram: Page 198, for example.

Inconsistent spelling: Brinkmate/Brinckmate (page 262). Malteses Cross/Maltese cross (page 280 – with another wrong diagram). Wolf’s/Wolff’s (page 331). The next page has Englisch/English.

Nonsensical game-score: Pages 321-322 have a game ‘Pillsbury v Lee, London 1889’. The two did not even meet that year. Ten years later they played a game which opened similarly, but the continuation given by Schiller was in fact what occurred, up to a point, in a different game, Pillsbury v Newman, Philadelphia, 1900. In short, yet another shambles.

Awful writing style: A specimen from page 343: ‘What on earth is going on here. White is giving away the store! Let’s see, Black has an extra rook, worth five clams or whatever, and can eat another one at a1. Must be winning, right?’

Inaccurate rating scale: According to the chart on page 408, a typical ‘International Grandmaster’ is likely to have an Elo rating of 2800 (200 points more than ‘World Class Grandmasters’), and the figure given for an International Master is 2000.

The third Cardoza washout, World Champion Tactics, was co-written with Leonid Shamkovich, not that that helps. The book has hardly started by the time White is being called ‘Black’ (page 14). On page 55 Kasparov is referred to as ‘Tal’. Page 36 has …Qa1 checkmate instead of …Qh1; that is the same mistake as the one mentioned above regarding the Encyclopedia of Chess Wisdom, and indeed the paragraph appears identically in both books. Yet it is not just a question of copying from one book to another. Even within World Champion Tactics there is duplication, such as the Alapin v Alekhine ending on that same page (page 36). It turns up again on page 61 (and both times there is the wrong claim that the event was an ‘international’).

Why anybody should wish to buy Schiller’s books is almost as incomprehensible as why anybody should be prepared to sell them.

Below is a C.N. item entitled ‘Crass’ which we wrote in 1985:

One book we most certainly shall not be reviewing in full is Grüenfeld Defense, Russian Variations by Eric Schiller, published by Chess Enterprises.

Grüenfeld is the novel spelling on the front cover. The back cover and spine prefer Gruenfeld. The Preface gives Grünfeld. The bibliography has Bruenfeld.

Ah yes, the bibliography, with its reference to the 1946 edition of Modern Chess Openings by ‘Griffith, P.C. & E.W. Sergeant’. P.C. Griffiths cannot be meant, since in 1946 he was not writing, he was being born. Presumably Mr Schiller was not sure whether the co-author was E.G. Sergeant or P.W. Sergeant, so he took one initial from each.

All this, though, is a mere antipasto, leading in to our tentative nomination for the most crass couple of sentences of 1985:

‘Dedication

To Harry Golombek, a friend and mentor, whose vast knowledge of chess, arbitin, and foreign languages I hop to someday acquire. May my writing retain its vitality as long as his has!’

As printed ...

(1054)

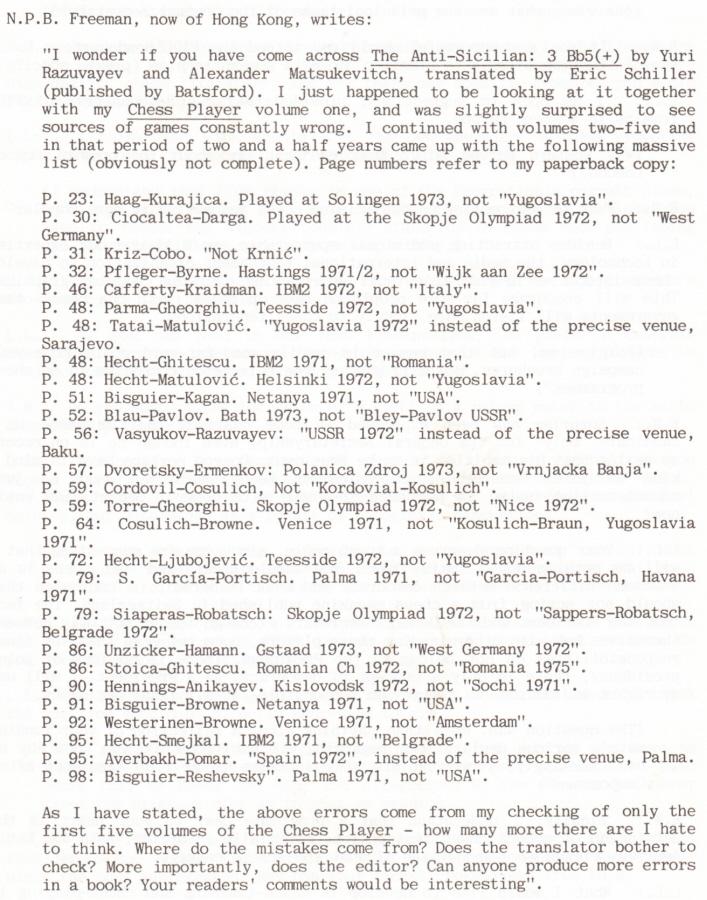

A contribution from Nigel Freeman concerning The Anti-Sicilian: 3 Bb5(+) by Y. Razuvayez and A. Matsukevitch (London, 1984):

Our comment at the end of the C.N. item:

We add just one point. The very first sentence of the book claims that after 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 ‘the move 3 Bb5 was first encountered in official competitions more than 100 years ago in the game Winawer-Steinitz, Paris 1867’. Doesn’t everyone know that 3 Bb5 was a familiar move back in 1851, even being played twice in the London tournament?

(1230)

The following appeared in C.N. 1737:

In 1984 Eric Schiller sent us two letters regarding Batsford Chess Openings. They were published in C.N.s 844 and 870, and in C.N. 1143 (page 53) we reported that C.N. had neither changed nor omitted anything whatsoever (except the correction of one typing error). Many readers of the Chess Linc/Chessline News computer system will therefore have been perplexed to see the following allegation by Mr Schiller dated 23 September 1988:

‘Winter has sent me loaded questions to which I initially replied with honest answers, only to see them manipulated to the point that a letter I sent supporting a position of Ray Keene’s, which was being attacked by Winter, was cited (not quoted in full as requested) as supporting Winter!’

This is pure invention, as the following facts demonstrate:

a) Mr Schiller was the one who opened the correspondence, so he was not replying to ‘loaded questions’ from us.

b) Mr Schiller never made any request that the complete texts be published.

c) Both of his letters were published in full (our own decision).

To prove the above, C.N. 1737 published the two letters again, this time reproduced photographically, exactly as received from Mr Schiller. We then concluded:

Mr Schiller’s allegation that we manipulated his letters is so injurious that readers will understand our reasons for taking up two pages to provide incontestable proof that it was an outright lie. We now await from him an unqualified retraction and apology.

They never came, of course.

Mikhail Tal died in 1992, but even reporting that elementary fact has proven an insurmountable hurdle for a number of writers. Other years proposed include:

1991: Larry Evans on the ‘Chess master Network’ (Internet).

1993: Graham Burgess on page 496 of The Mammoth Book of Chess.

1994: Bjarke Kristensen and Don Maddox on page 19 of their book about the Kasparov v Anand match.

Not to be outdone, pages 50 and 368 of World Champion Openings by Eric Schiller refer to a game ‘Unzicker v Tal, Hamburg, ...1996’.

(2240)

In the carelessness stakes who can match Eric Schiller? Take his 1999 ‘work’ Hypermodern Opening Repertoire for White as a random example. It opens up (i.e. the very first line of page 5) with the reference ‘TABLE OF CONTENSTS’ in large letters and closes down (i.e. the very last line of page 296) with an index reference to a player whose name is truncated to a mere ‘Van der’. Has any other chess book both started and finished in such slovenly fashion?

(Chess Café, 1999)

On page 313 of his blunderful book Encyclopedia of Chess Wisdom (Cardoza Publishing, 1999) Eric Schiller gives Legall’s famous brevity (5 Nxe5) as having been played in 1801 (i.e. nearly a decade after his death), and page 335 presents ‘Congdon vs. Delmar, New York 1980’ instead of 1880.

In the same book Schiller cautions, ‘We must be careful not to believe everything we read …’ That appears on page 351 but would have been better on the front cover.

(2255)

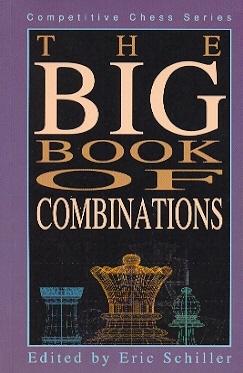

The Encyclopaedia of Chess Middlegames (Chess Informant, Belgrade, 1980) was appropriated by Eric Schiller in his volume The Big Book of Combinations (Hypermodern Press, San Francisco, 1994). It is customary for writers of such works to ‘borrow’ widely from each other, but Schiller went far beyond that. He plundered hundreds (many hundreds) of positions, and gave himself away by indiscriminately repeating countless mistakes from the earlier tome.

Before turning to the facts of the case, it is worth bearing in mind Schiller’s version of events, from his Preface (page 3):

‘The combinations include most of the most famous and well-known examples, but there are also many positions taken from rare and unexplored literature. You are sure to find many combinations you have never seen before, no matter how many books you have studied.’

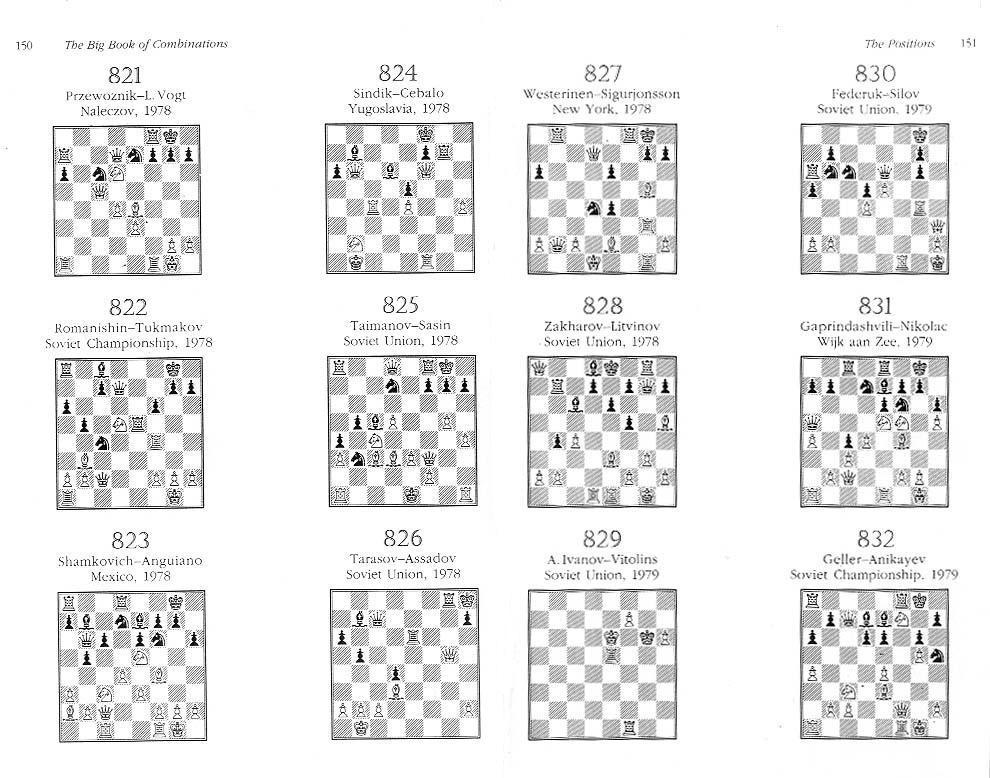

The Big Book of Combinations presents the positions in chronological order, and we opened it, at random, at pages 150-151. Schiller offers 12 positions there from games played in 1978 or 1979.

So how many of them had appeared in the Encyclopaedia? Answer: all 12 of them. Moreover, five of the positions are given no venue by Schiller beyond a mere ‘Soviet Union’. Why? Because that is all the Encyclopaedia gave.

Clearly, a more extensive spot-check was required. We therefore turned back to page 17, where the twentieth-century positions begin, and went through them until around the end of the Second World War (page 38). That accounted for 132 positions. Astoundingly, it emerged that all but about half a dozen of them had been lifted, without a word of credit, from the Encyclopaedia. Elsewhere in Schiller’s book, we discovered, it was the same story. Realizing that none of the positions from the 1950s had yet been scrutinized, we invited a colleague (who possesses neither book) to pick any year from that decade. He chose 1958, and we duly informed him that a) for that year Schiller gives 13 positions, and b) all 13 had appeared in the Encyclopaedia.

On page 200 of the May 1985 BCM we referred to the unreliability of the Encyclopaedia and pointed out, inter alia, that it wrongly gave Capablanca’s game against Fonaroff as played in 1904 instead of 1918, while the Cuban’s win over Mieses was dated 1931 rather than 1913. Schiller, however, was oblivious to all this, and his 1994 ‘effort’ blithely copies these and numerous other mistakes from the Encyclopaedia.

For example, the first position from our lengthy spot-check (i.e. on page 17 of Schiller’s book) is labelled ‘Schlechter – Metger, Vienna, 1899’. That is certainly what page 202 of the Encyclopaedia had also stated, but Black in that game (a famous Schlechter win) was Meitner. Indeed, two pages earlier Schiller offered a similar position and mentioned Meitner on that occasion, although the date was given as ‘1889’ and the venue was bafflingly rendered as ‘Bec’. Why? Because Schiller did not realize that Beč means Vienna in Serbo-Croat.

Page 183 of Schiller’s book states, ‘In general, we have provided first names or initials only when there might be some question about the identity of the player’, but no such effort has been made. Page 18 has ‘Lasker – Bauer USA, 1908’, i.e. exactly what the Encyclopaedia put on page 251. This leaves the reader to assume that White was Emanuel Lasker, but in reality the position was won by Edward Lasker. (His opponent was Arpad Bauer, and the position was given on page 100 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 15 March 1908.) Of course, Edward Lasker did not visit the USA until well after 1908, but there is a simple explanation. Contrary to the ‘USA’ claim in the Yugoslav book, automatically parroted by the American purloiner, the venue was Berlin, Germany.

Page 138 of the Encyclopaedia labelled a position ‘Eliskases – Mori Birmingham 1937’. Schiller (page 34) self-evidently gives the same spelling, unaware that Black was W. Ritson Morry. On the next page Schiller has this caption: ‘Kito – Shelhaut Hastings, 1938’. That, naturally, is identical to what appeared in the Encyclopaedia (page 146), but the players’ names should read Kitto and Schelfhout. Another 1938 game, on page 249 of the Encyclopaedia, was ‘Tylor – Thomas Bryton 1938’. It may seem obvious that ‘Bryton’ should read Brighton, but it was not obvious enough for Schiller; on page 36 he too uses the spelling ‘Bryton’, adding for good measure an original mistake of his own by changing Tylor to ‘Tyler’.

Schiller’s book can be dipped into on any page for more of the same. A further typical case concerns ‘Parr – Waitkroft, Netherlands 1968’, which is how the position is presented in the Encyclopaedia (page 32) and, consequently, also in Schiller’s book (page 99). Yet even a novice writer might be suspicious of a spelling like ‘Waitkroft’ or capable of identifying the players and finding the proper venue and year (i.e. F. Parr v G.S.A. Wheatcroft, London, 1938) in a very common book, The Golden Treasury of Chess by F. Wellmuth. (The exact occasion was the City of London Chess Club Championship, and Frank Parr annotated his brilliancy on page 318 of the July 1938 BCM.)

Readers who own the Encyclopaedia of Chess Middlegames and The Big Book of Combinations will see for themselves that the copying perpetrated by Schiller is so extensive that a series of further exposés of his conduct could easily be written, each with a different set of examples. There would certainly be no need for such articles to plagiarize each other.

(2965)

Regarding Tylor v Thomas, Brighton, 1938, see too C.N. 9092.

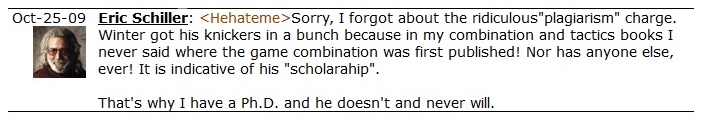

Eric Schiller’s response on his chessgames.com page:

On 24 May 2011 Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) wrote to us:

‘Schiller is an ego-driven imbecile.’

Addition on 1 September 2022:

The founder of Hypermodern Press, James Eade (Menlo, CA, USA), informs us:

‘I severed all ties with Eric Schiller after reading your review of his Big Book of Combinations. I tried to produce quality books through Hypermodern Press, but I never should have gotten involved with him.’

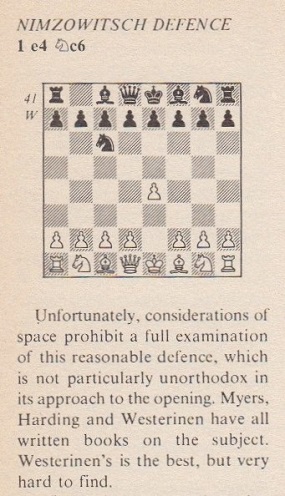

In 1987 Batsford brought out Unorthodox Openings by Joel Benjamin and Eric Schiller. In the section on Nimzowitsch’s Defence (1 e4 Nc6) the authors wrote (page 50):

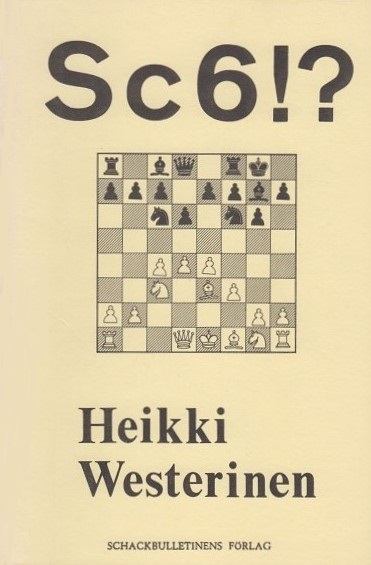

‘Myers, Harding and Westerinen have all written books on the subject. Westerinen’s is the best, but very hard to find.’

In the April-May 1988 issue of The Myers Openings Bulletin (page 16), Hugh Myers commented:

‘Hard to find! I should say so. I’ve never seen it, and other theoreticians have told me that they don’t know of it. I have seen a book by Westerinen titled Nc6! – it has nothing to do with 1 e4 Nc6 ... You don’t really think that Benjamin and Schiller would have judged a book as “best” without ever seeing it!?’

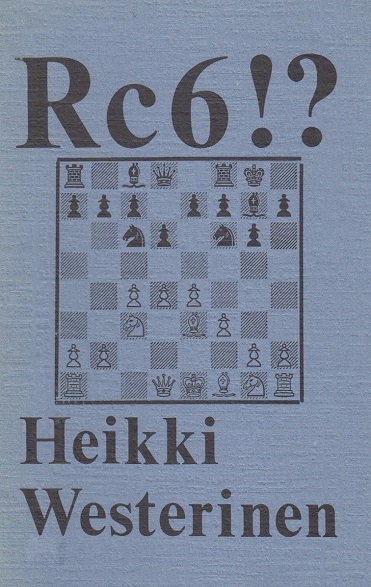

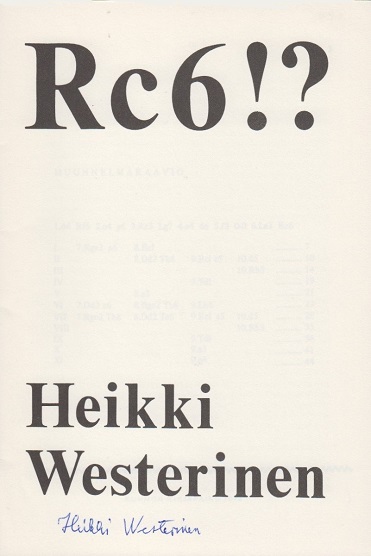

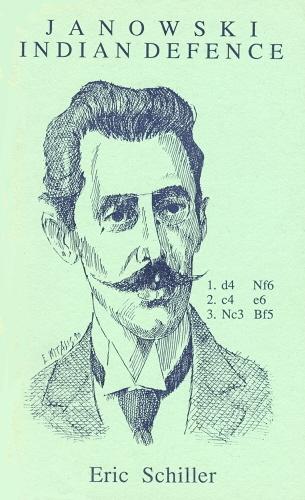

In the January-March 1993 issue of the same magazine, Myers reported that in 1988 Schiller, then temporarily in Hawaii, had insisted that a book on 1 e4 Nc6 by Westerinen did exist, and that a copy was in his library in Chicago. He promised to give Myers further information upon his return home. The remainder of the episode is easily guessed. Schiller kept silent and Myers eventually secured a copy of the book by Westerinen. It was published in Swedish in 1972 (also in Finnish the same year, under the title Rc6!?) and dealt only with 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 f3 O-O 6 Be3 Nc6.

(Kingpin, 1993)

Below are the cover page and title page of our inscribed copy of the original Finnish edition:

In C.N. 9493 Thomas Ristoja (Helsinki) reported that he had translated the booklet from Finnish into Swedish but that his name was omitted from the Swedish edition. The same C.N. item showed the relevant passage from page 50 of Unorthodox Openings by Benjamin and Schiller:

The 1 e4 Nc6 episode related above reminds us of a letter dated 2 January 1988 from Donald Schultz:

As mentioned on page 294 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, in 1996 Eric Schiller came out with a volume on Rudolf Spielmann. ‘Rudolf’ appeared on the front cover, but elsewhere (including the title page and back cover) the name was misspelt ‘Rudolph’.

A further recent book by Mr Eric Schiller is 100 Awesome Chess Moves, Cardoza Publishing again being the culprit. The illiteracy begins on the front and back covers (‘This collection … are …’). Those unfortunate enough to own a copy are also invited to turn to the ‘Index of Games’ (pages 286-287) and hunt for any correct page references.

(Kingpin, 2000)

(6013)

From Play the Tarrasch by L. Shamkovich and E. Schiller (Oxford, 1984), page 1:

‘We consider the Modern period to have begun when Bronstein was born – in 1924.’

(875)

On 17 February 2002 Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) wrote to us:

‘As far as Evans and Parr are concerned, I think what it basically comes down to is that both have some sort of delusions that they know something of chess history, whereas in truth they both know very little. Thus the only real defense they have is scurrilous attacks on those who point out their absurd errors. Schiller belongs to the same slovenly group.’

Page 10 of Learn from Bobby Fischer’s Greatest Games by Eric Schiller (New York, 2004)

Page 12 of Learn from Bobby Fischer’s Greatest Games by Eric Schiller (Las Vegas, 2009)

(6206)

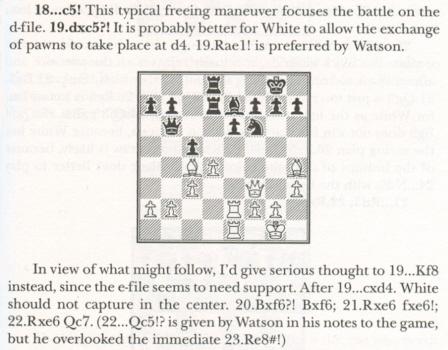

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) draws attention to page 197 of Complete Defense to King Pawn Openings by Eric Schiller (New York, 1998), concerning the game is Ghinda v W. Watson, Thessaloniki, 1988:

The position after 22 Rxe6:

Schiller observes that Watson’s suggestion 22...Qc5 allows 23 Re8 mate. So, instead, Schiller recommends 22...Qc7, overlooking that it allows 23 Re8 mate.

(6281)

As noted in Historical Havoc (an article we published in 1998), page 13 of World Champion Openings by Eric Schiller (New York, 1997) referred to ‘Emil Zukertort’. Any respectable writer would, of course, take the earliest possible opportunity to correct the blunder. Consequently:

World Champion Openings by E. Schiller (first edition – New York, 1997)

World Champion Openings by E. Schiller (second edition – New York, 2002)

World Champion Openings by E. Schiller (third edition – Las Vegas, 2009).

A few lines later, in all three editions, mention is made of another world championship challenger, Isidore [sic] Gunsburg [sic].

(6383)

It is common knowledge that Capablanca participated in only one Olympiad (Buenos Aires, 1939), though not common enough. From page 35 of The Big Book of Chess by Eric Schiller (New York, 2006):

‘The reigning champion, Jose Capablanca, had played in the initial 1927 Olympiad event.’

(6443)

One of Euwe’s most famous wins is the ‘Pearl of Zandvoort’, the 26th game of his 1935 world title match against Alekhine. See, for instance, page 150 of Euwe’s From My Games 1920-1937 (London, 1938) and such well-known books as Wellmuth’s The Golden Treasury of Chess, Fine’s The World’s Great Chess Games and Schonberg’s Grandmasters of Chess. Various chess encyclopaedias (e.g. by Sunnucks, Golombek and Brace) have an entry for the ‘Pearl of Zandvoort’, and it is, in short, a matter on which no half-competent writer would go wrong.

From page 158 of The Big Book of Chess by Eric Schiller (New York, 2006):

The Euwe win given by Schiller as the ‘Pearl of Zandvoort’ was played in Amsterdam.

(6683)

A novel of which we have no knowledge was mentioned on page 299 of The Big Book of Chess: ‘The Queen’s Gambit by Walter Titus.’

Under the heading ‘Incorrigible’ the following item appeared in C.N. 3216 (see also page 249 of Chess Facts and Fables):

‘Wilhelm Steinitz did not become World Champion until he was over 58 years old, on May 26, 1894.’

That is what Eric Schiller persistently claims. We drew attention to it in C.N. 2241 (i.e. on page 89 of the 1/1999 New in Chess). Far from correcting his spectacular gaffe, Schiller subsequently posted it at a second website, as we noted in C.N. 2302 – see page 98 of the 5/1999 New in Chess. Yet even then Schiller refused to make a correction, so in C.N. 2468 (page 105 of the 1/2001 New in Chess) we mentioned the matter a third time.

What, then, is the situation today, all these years later? It will surprise no-one to learn that Schiller’s website still affirms:

‘Wilhelm Steinitz did not become World Champion until he was over 58 years old, on May 26, 1894.’

That summary was written in 2004. Today, a dozen years after we first pointed out the spectacular gaffe, the same claim about Steinitz is still on-line, under the title ‘Oldest World Champion’ in a signed article by Schiller at a website which states that it is supervised by him: Chesscity.com.

(6890)

Addition on 5 January 2013: the above link no longer works.

On 3 May 2010, the day Florencio Campomanes died, Eric Schiller posted the following message at chessgames.com:

‘An evil man who is not going to be missed. Thoroughly corrupt persecutor of those who wanted chess to move forward. Destroyer of our beloved World Championship.

Some champagne with dinner tonight to wish him good riddance!’

From another chessgames.com page later the same day:

On the back cover of Attack with the Boden-Kieseritzky-Morphy Gambit by Eric Schiller (New York, 2011):

Concerning Tony Miles’ celebrated two-word review in Kingpin of Unorthodox Chess Openings by Eric Schiller, Raymond Keene wrote the following utter piffle on Schiller’s chessgames.com page:

Half a dozen typos in half a dozen lines.

Source: page 12 of a book published by Impala Film Division in 2008: Battle of Bonn (World Chess Championship 2008) by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller.

(8142)

On page 873 of Gyula Breyer. The Chess Revolutionary (Alkmaar, 2017) Jimmy Adams writes that he started the book over 30 years ago.

From page 350 of Grandmaster Insides by Maxim Dlugy (Ghent, 2017):

‘In 1989, I asked my friend Eric Schiller how he manages to write and publish so many books. He explained that he just compiles the information and then inserts simple to understand commentaries with basic tactics to explain the ideas.

He claimed it took him three days of work to put out a book.’

(10555)

Wanted: more detailed local (i.e. Breslau/Wrocław) information about Marshall’s ‘Gold Coins’ Game, and also about the loser.

Other games where a queen moves to KKt6 (i.e. g6 or g3) are discussed in The Fox Enigma.

Frank James Marshall by Frederick Orrett (see C.N. 9722)

Regarding the alleged gold coins episode, the English-language Wikipedia page on the game currently cites, of all things, a 2006 book published by Cardoza:

‘Eric Schiller wrote, “others say they were just paying off their wagers”.’

C.N. 12063 referred to the existence of a Wikipedia project group created to ‘improve information on chess-related articles’. The project group states:

‘Print sources are generally considered reliable, but certain authors such as Eric Schiller and Raymond Keene have a reputation for unreliability.’

(12129)

See too Chess Journalism and Ethics, An Alekhine Blindfold Game, Copying and A Chess Mess, as well ‘Ex Acton ad Astra’ on pages 18-33 of the Spring 2007 issue of Kingpin.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.