Edward Winter

W.H. Cozens (Ilminster, England) writes:

‘From the Chess Memoirs of Dr Platz (Coraopolis, 1979), page 51:

“I was present when Reuben Fine asked him (A. Rothman) ‘Is it true that you know the columns of MCO by heart?’ And he answered: ‘Yes, it is true.’”

Some of today’s young hopefuls with similar ambitions might do well to reflect that the end product of this astonishing feat was not a Karpov or a Capablanca, but ... A. Rothman.’

(413)

For further information about Rothman, see C.N.s 4930, 7350 and 7357.

C.N. 889 quoted from page 49 of the McFarland book The Literature of Chess by John Graham (Jefferson, 1984) a bizarre comment on an openings book by Al Horowitz:

‘This is, at first sight, a massive volume (790 pages), which simply duplicates the MCO by presenting all playable lines of all chess openings.’

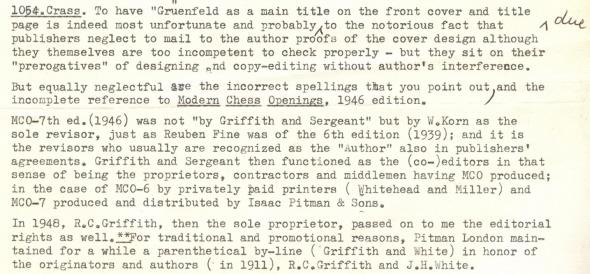

Below is the full text of C.N. 1054 (entitled ‘Crass’), written in 1985:

One book we most certainly shall not be reviewing in full is Grüenfeld Defense, Russian Variations by Eric Schiller, published by Chess Enterprises.

Grüenfeld is the novel spelling on the front cover. The back cover and spine prefer Gruenfeld. The Preface gives Grünfeld. The bibliography has Bruenfeld.

Ah yes, the bibliography, with its reference to the 1946 edition of Modern Chess Openings by ‘Griffith, P.C. & E.W. Sergeant’. P.C. Griffiths cannot be meant, since in 1946 he was not writing, he was being born. Presumably Mr Schiller was not sure whether the co-author was E.G. Sergeant or P.W. Sergeant, so he took one initial from each.

All this, though, is a mere antipasto, leading in to our tentative nomination for the most crass couple of sentences of 1985:

‘Dedication

To Harry Golombek, a friend and mentor, whose vast knowledge of chess, arbitin, and foreign languages I hop to someday acquire. May my writing retain its vitality as long as his has!’

As printed ...

In response, Walter Korn (San Mateo, CA, USA) wrote to us on 21 December 1985 (C.N. 1103):

James J. Barrett (New York, NY, USA) writes:

‘P.W. Sergeant died in 1952. An almost insultingly brief “obituary” appeared in the BCM for November of that year (page 324). No mention of his long connection with the BCM. No mention of Morphy’s Games of Chess. Half a sentence skirts the subject of his considerable non‑chess publications. No mention of his date of birth or death. The only book mentioned is his A Century of British Chess– and, oh yes, “helping R.C. Griffith with two editions of Modern Chess Openings”. The whole tone of this small paragraph that serves as an obituary is cold and unfeeling, and there was no follow-up. There must be a story here. Did he have a falling‑out with the BCM? And I could not find even a mention in CHESS.’

(1268)

Henry Ernest Atkins

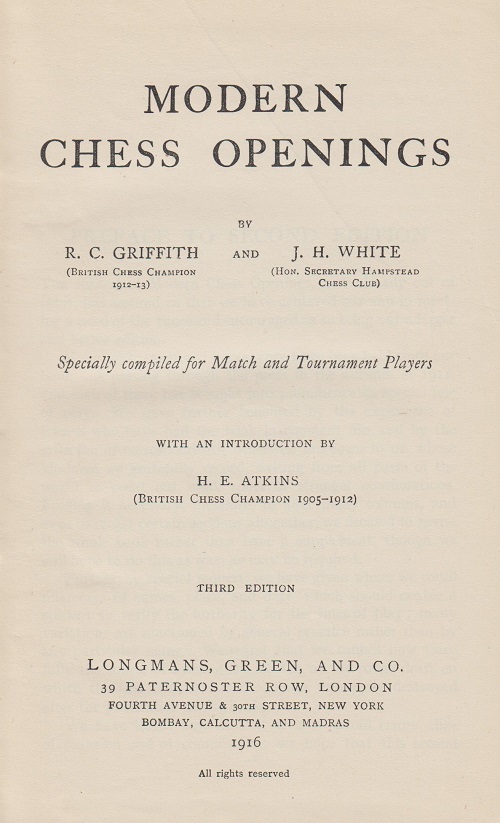

H.E. Atkins wrote little about chess, but below is a brief example of his prose, written in December 1911 and included in the Introduction to the first three editions of Modern Chess Openings by R.C. Griffith and J.H. White:

‘Few players as a rule get the advantage that they might do from bookwork, and the reason is that the work is not done thoroughly enough, the moves are played over and learnt by heart, without being properly appreciated. Every move should be gone into and the reason found out; in fact it is hardly an exaggeration to say that the slower the variations are gone over the better. It undoubtedly requires great patience and perseverance to go through openings in the way suggested, but the result fully justifies the trouble. In ordinary practice games it is very rare for much trouble to be taken over the opening part of a game; players do not really try to find the best possible move as long as they can find an apparently fairly good one, and accordingly very little improvement is made in opening strategy.

Clocks should be used more than is the case at present. In most clubs they are only forthcoming when matches are taking place, and players feeling that the state of things is unusual become nervous and fail to do themselves justice.

It would too, I think, be a useful thing if players occasionally would agree on a series of games where play was to stop after each had made 20 moves.

Such games would be excellent practice for match chess. They would take up comparatively little time, and would, I think, lead to great improvement.

Openings like the Ruy López and QP Opening are exceedingly difficult to play well, and are not suited to the inexperienced player. The principles involved are too difficult to be properly understood, and the mere learning off of the moves is of little good from an instructive point of view.

Openings of a more decisive character, such as the King’s Gambit, Vienna, Scotch, Danish Gambit, and so forth, are of much greater value.’

(3836)

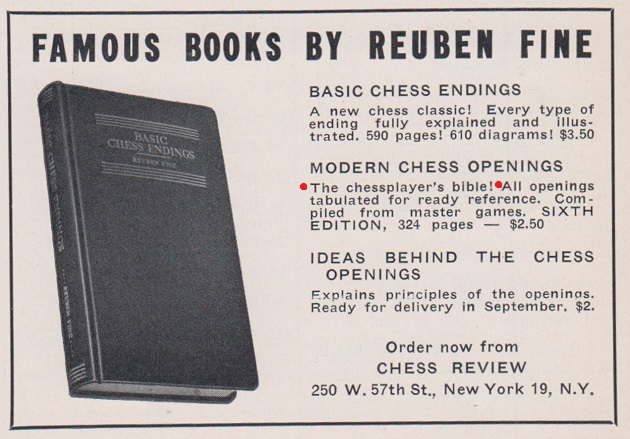

‘Well begun is half done’, says the back-cover blurb of MCO-14, and it is worth recalling how the series started (in 1911). In his reminiscences on pages 145-151 of the April 1932 BCM, the magazine’s then editor, R.C. Griffith (1872-1955) wrote:

‘It might interest readers to know how Modern Chess Openings came into being. I got a notebook and put down in it variations of certain openings which pleased me and my dear old friend, J.H. White, hon. secretary of the Hampstead Chess Club, whose death as the result of an accident everyone deplored, said to me “You have got so much there, why do you not complete a book on openings? I will help you.” With his help we brought the book out.’

(Kingpin, 2000)

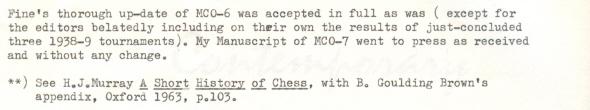

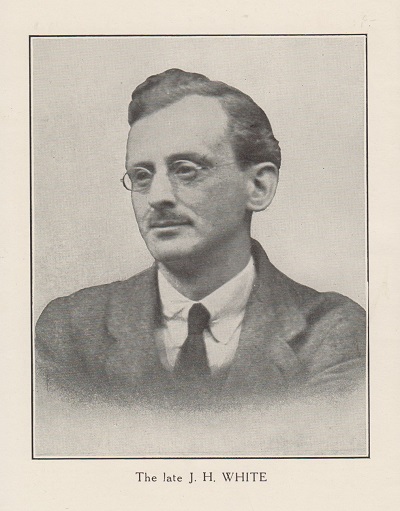

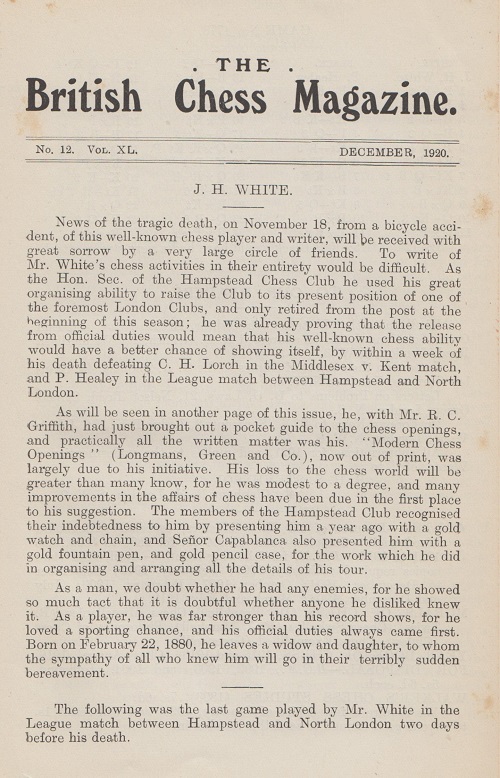

J.H. White died in a cycling accident on 18 November 1920, at the age of 40 (BCM, December 1920, page 369). Page 133 of the February 1921 Chess Amateur paid a fulsome tribute to him (‘A small collection of Mr White’s best games would be a very acceptable publication. No player risked more, or was more fertile in new ideas.’) when publishing the following forgotten miniature:

N.N. – J.H. White

Hampstead (date?)

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 b5 7 Bb3 d5 8 dxe5 Be6 9 c3 Bc5 10 Nbd2 O-O 11 Bc2 f5 12 exf6 Nxf6 13 Nb3 Bd6 14 Nbd4 Nxd4 15 Nxd4 Ng4 16 h3

16…Qh4 17 Nxe6 Nxf2 18 Qxd5 Bh2+ 19 Kxh2 Ng4+ 20 Kg1 Rxf1+ 21 Kxf1 Qf2 mate.

(2550)

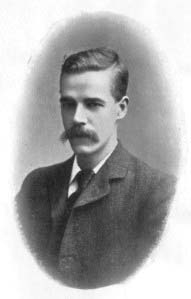

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) sends this report from page 3 of the Hendon and Finchley Times, 26 November 1920:

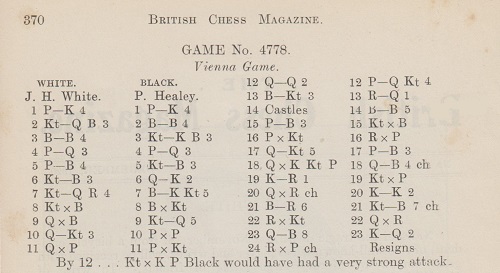

Below is the coverage of White’s death in the December 1920 BCM (frontispiece and pages 369-370):

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Bc5 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d3 d6 5 f4 Nc6 6 Nf3 Qe7 7 Na4 Bg4 8 Nxc5 Bxf3 9 Qxf3 Nd4 10 Qg3 exf4 11 Qxf4 dxc5 12 Qd2 b5 13 Bb3 Rd8 14 O-O c4 15 c3 Nxb3 16 axb3 Rxd3 17 Qg5 c6 18 Qxg7 Qc5+ 19 Kh1 Nxe4 20 Qxh8+ Ke7 21 Bh6 Nf2+ 22 Rxf2 Qxf2 23 Qf8+ Kd7 24 Rxa7+ Resigns.

J.H. White co-edited with R.C. Griffith the first three editions of Modern Chess Openings.

The Preface to the fourth edition, by Griffith and M.E. Goldstein (London, 1925), began:

‘The tragic accident to Mr J.H. White in the latter part of 1920 deprived the chess world of a brilliant player and writer, who did so much in bringing Modern Chess Openings into being.’

Page 388 of the December 1920 BCM carried a highly positive review by J.H. Blake of another work co-written by Griffith and White, The Pocket Guide to the Chess Openings (London, 1920):

(10139)

An introductory extract from the lengthy item C.N. 10272:

We offer a solution to the long-standing mystery of how the ‘Pittsburg(h) Trap/Variation’ obtained its name(s).

Modern Chess Openings by R.C. Griffith and J.H. White (London, 1913), page 92. (See too many other editions.)

From page 78 of the first volume of Chess Characters by G.H. Diggle (Geneva, 1984), in which he referred to himself in the third person as the ‘BM’ (‘Badmaster’):

‘One of the BM’s earliest opponents was an eccentric but versatile Spalding lady some 50 years his senior, who for some fantastic reason was absolutely fascinated by the names of the Openings and who would turn over the pages of the BM’s MCO as though it were a picture book. She would even get the BM to go through with her the first three or four moves of any opening with a name that particularly “turned her on”, such as the Giuoco Piano or what she called the Kaiseritzky Gambit. Her main chess ambition was not to win a game (which she was shrewd enough to perceive would never happen) but to play an opening with a good resounding title, which gave her the same feeling of accomplishment as that of a ballroom dancer who had just performed the “Mayfair Quickstep” or the “Royal Empress Tango”. In her quest for additional strings to her bow she once discovered the “Max Lange” (16 columns including innovations from Marshall and Tartakower) and on being informed that Lange was a deceased nineteenth-century Master remarked that “he must have had a brain to have invented all that”.’

Even so, the Spalding lady’s delightful belief about Max Lange’s brainpower is less naive than the misapprehension of various newspaper and magazine editors that the chess columnist/correspondent on their payroll requires any time, let alone special grey matter, to fabricate his daily or weekly feature when it largely consists of bare (or barely annotated) game-scores which can be downloaded by anyone at the press of a button.

(3671)

The article below by the ‘Badmaster’ is reproduced from page 25 of our publication Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It originally appeared in the August 1977 issue of Newsflash.

‘The bilious and impecunious Badmaster, glaring over last month’s Newsflash with a malevolent eye, was delighted to find that the price of Modern Chess Literature, and Books on the Openings in particular, seems to be coming under fire. For if the BM ever agreed to be interviewed on Television and was finally asked, “Looking back, Badmaster, over half a century of lost games, is there any particular factor which you feel has had the greatest influence on your disastrous career?”, he would reply in ringing tones: “Buying Books on the Openings”.

A particularly shameful instance of the BM being let down by these treacherous tomes occurred during the London Championship Tournament 1945. An awful morning had dawned when the official “Order of the Day” ran (inter alia) – “Round 6. Sir George Thomas (White) Badmaster (Black)”. Surmising (correctly) that his august opponent would open P-K4 and go for a quick win, the BM sat up most of the previous night with Modern Chess Openings (Griffith and White), selected the Petroff Defence, distended his brainbox with all 12 columns given, and arrived at the arena next day with the full cargo still on board. The result was that for the first eight moves the BM played with a precision which confounded the critics, but then Sir George (who had previously played like the orthodox gentleman that he was) suddenly revealed himself (in Marxist language) a deviationist of the basest stamp. In short, his ninth move was nowhere to be found. Deserted by MCO, the BM found himself in the same plight as David Balfour in Kidnapped when he ascended the tower in total darkness, only to find suddenly that “the stair had been carried no further” and that he was left to proceed on his own into the void. This he did, and perished about the 20th move. But the most infamous part of the story has yet to come. Of the two unworthy authors responsible for the BM’s downfall White (like Jacob Marley) had long been dead; but R.C. Griffith (a most sprightly “Scrooge”) was not only very much alive but actually a spectator at this very tournament. Just as the BM resigned, R.C.G., who was standing by, bestowed upon him a whimsical yet kindly smile, which plainly said: “Never mind, young man, you’ll know that variation another time”. He then went away beaming all over his face. But for his benevolent appearance and charming manner, the BM could have “felled him like a rotten tree”.’

(6046)

An inscription by Elaine Saunders in one of our copies of the seventh edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1946):

An extract from A Catastrophic Encyclopedia:

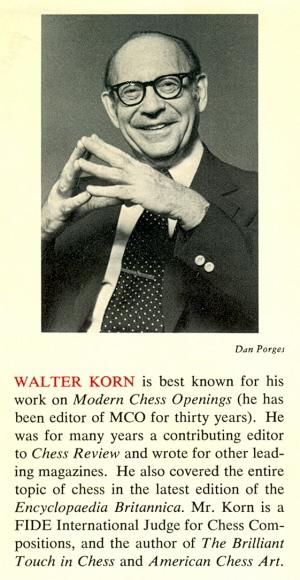

Page 131: the entry on Modern Chess Openings (21 lines) does not even name Walter Korn, the person responsible for the book for the past 50 years.

From David Picken (Greasby, England):

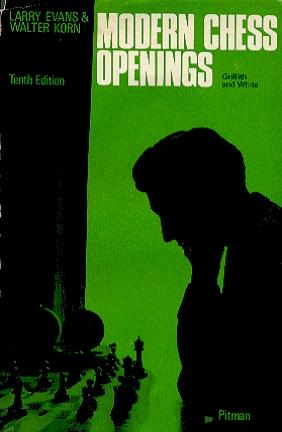

‘On the dust cover of the tenth edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1965) authored by Walter Korn and Larry Evans but mainly by the latter there is a silhouette of a chessplayer studying a board. He is not identified but does, in my view at least, resemble Evans.’

(4136)

See Chess Silhouettes.

In a 1978 syndicated article (see, for instance, page 34 of The Oregonian, 7 August 1978), Larry Evans wrote regarding publication of the eleventh edition:

‘Modern Chess Openings by Korn is so famous that the middle game has been redefined as that phase of chess which begins where MCO ends. When I revised the previous edition, I felt entrusted with the keys to the kingdom.’

James M. Aitken had fine judgement and was not averse to using a ‘sophisticated’ word or Shakespearean quote to underscore his point, as shown by this extract from his review of the ninth edition of Modern Chess Openings (in the January 1958 BCM, pages 15-16):

‘The task of compilers of opening guides (at least on the scale of MCO) is nowadays sisyphean. It is never “done when ’tis done”; rather when published it is already beginning to be undone.’

(3766)

From Historical Havoc:

The inadequate monitoring of new chess literature is another problem. The 13th edition of Modern Chess Openings was published at the beginning of the 1990s, yet it is hard to recall any authoritative critique that compared it to earlier editions and to other single-volume openings manuals. The public’s interests were forgotten long ago. Much literature is sold by mail, but the USCF, for instance, barely mentions certain high-quality books and is less than candid about the deficiencies of many that it does endeavour to sell, not to say off-load. Chess Life is just one of many magazines less concerned with serious reviewing than with sales patter. Little wonder that bungling authors can hope to escape scot-free in the crowd.

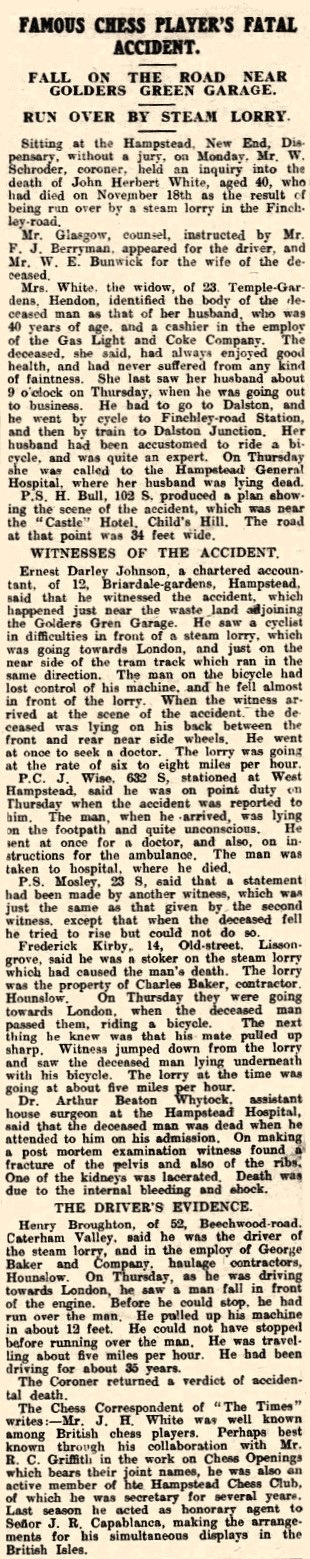

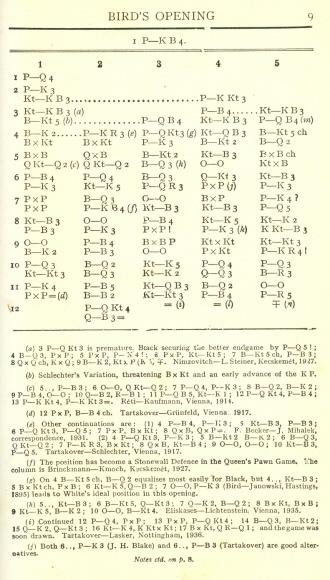

Referring to our article on Copying, Owen J. Clarkin (Ottawa, Canada) writes:

‘I should like to point out an example concerning:

(i) Modern Chess Openings, seventh edition, revised by W. Korn under the editorship of R.C. Griffith and P.W. Sergeant (London, 1946);

(ii) Practical Chess Openings by R. Fine (Philadelphia, 1948).

Regarding the Center Counter Game, I found that ten columns of variations and the corresponding footnotes are virtually identical. See pages 30-32 of MCO and pages 35-38 of PCO. Other chapters where copying is notable include the following:

Alekhine’s Defense: Columns 1 and 2 of MCO v 1 and 2 of PCO; column 23 of MCO v 20 of PCO; column 21 of MCO v 17 of PCO.

Bird’s Opening is practically identical for most variations and footnotes.

The Bishop’s Opening has many copied sections.

It is not clear to me who copied whom, or whether this copying has been noticed before. The editors of MCO credit Fine as the reviser of the sixth edition of MCO (see page v of the seventh edition), but Fine makes no mention in PCO of his involvement in the sixth edition of MCO.’

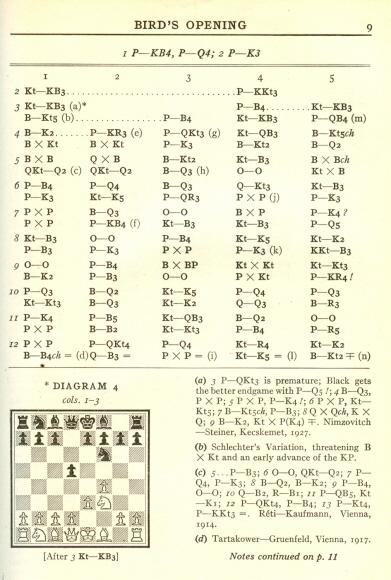

Our correspondent’s final paragraph holds the key to the affair: Reuben Fine had brought out a ‘completely revised’ edition of MCO in 1939. Below is part of the three books’ coverage of one of the above-mentioned openings:

From left to right: MCO-6 by Fine (1939), MCO-7 by Korn (1946), Practical Chess Openings by Fine (1948)

Thus Fine’s material in the sixth edition of MCO was used both by Korn in the seventh edition of MCO and by Fine himself in PCO. The rights and wrongs of such practices seem far from clear-cut.

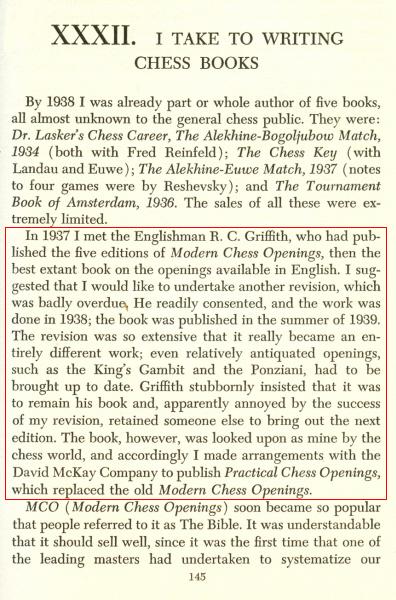

The following text appeared on the dust-jacket of Practical Chess Openings:

‘Several years ago, when the author was on an exhibition tour, the master of ceremonies in St Louis introduced him to the audience with the remark: “Ladies and Gentlemen, it gives us great pleasure to have with us tonight the author of the Bible.” The “Bible” that he referred to was Modern Chess Openings, sixth edition, to which this book is a sequel.’

The blurb also asserted: ‘Reuben Fine is the world’s leading authority on chess.’ As regards the MCO/PCO affair, Fine gave his side of the story on page 145 of his book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

(5269)

Chess Review, August-September 1943, page 243

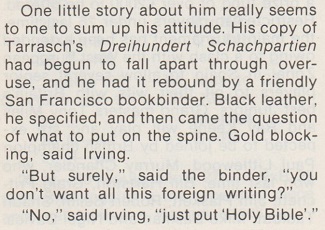

A remark by Adam Hart-Davis in a tribute to Irving Chernev on page 278 of CHESS, December 1981:

Adam Hart-Davis also related the story on page 8 of 200 Brilliant Endgames by Irving Chernev (New York, 1989):

(11189)

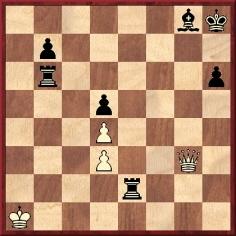

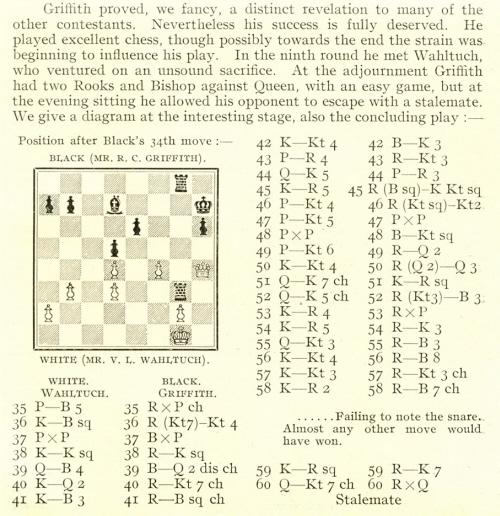

In a discussion of aesthetics, C.N. 2257 (see page 145 of A Chess Omnibus) gave the following diagram (V.L. Wahltuch v R.C. Griffith, British championship, Richmond, 1912):

White to move

We commented:

In this position (taken from page 364 of the September 1912 BCM) Wahltuch preferred 60 Qg7+ to 60 Qxg8+. Is his choice aesthetically better, perhaps because it is a shorter move and less showy? Or is showy the word to describe 60 Qg7+, because it leaves Black with more redundant material? Or again, is it all much of a muchness?

Below is the final phase of the game, as published in the BCM:

Griffith, who won the championship tournament, recalled the game on page 151 of the April 1932 BCM:

‘My success at Richmond was unexpected by myself and everybody else. Of course, I was particularly lucky. Atkins retired that year, and several players who invariably used to beat me never entered; why they accepted my entry I do not know. I wrote to Rees and said it was the only chance I should ever have of playing for the championship in the summer, and perhaps my special pleading softened the hearts of the selection committee. The work on MCO certainly bore fruit at Richmond, and J.H. White backed me up all he could, but the only chessplayer I could get to bet that I should be in the first half was J. Schumer. I was fortunate to lead throughout, although I made an ass of myself against V.L. Wahltuch. The heading the next morning in The Standard was amusing, “Griffith’s brilliant stalemate”. This was adding insult to injury. I found it very hard work, and my wife said I looked a wreck at the end of it, but these congresses are invariably well run, and I wish I could afford the time to enter another.’

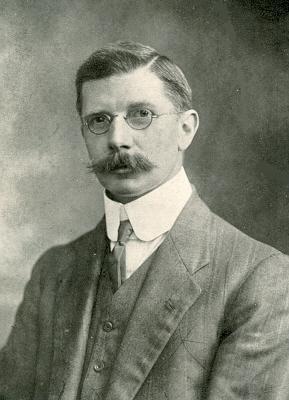

Richard Clewin Griffith (BCM, October 1912)

(5608)

From page 5 of the Chess Amateur, October 1912:

(10222)

In the above 1932 passage, Griffith slightly misquoted the erroneous heading in the Standard (London), 22 August 1912, page 11:

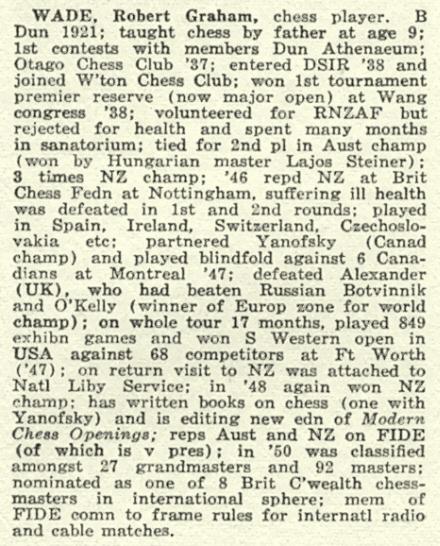

Below is Robert Wade’s complete entry on page 240 of Who’s Who in New Zealand (Wellington, 1951):

The bibliographical references may seem surprising at first sight, but page vii of Chess the Hard Way! by D.A. Yanofsky (London, 1953) acknowledged Wade’s collaboration. On page v of the eighth edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1952) the Editor, Walter Korn, related in detail the extent of the contribution by Wade.

(7295)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘Bob Wade did indeed believe that he would be credited on the title page as the editor of Modern Chess Openings, as he told me several times, including in 1949 when he enlisted me to write a section on the Queen’s Gambit Declined. He claimed to have done the great majority of the work entailed in the book’s revision.

He was angry at what he perceived as Korn’s diminishing of his contribution when Modern Chess Openings appeared, and vowed that he would never work with Korn again.’

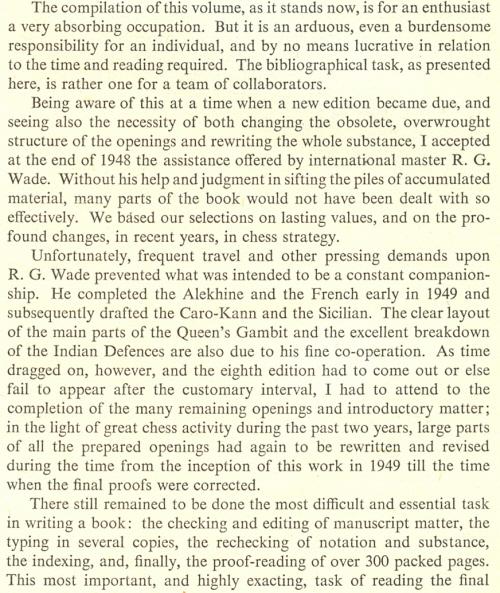

Below is the relevant part of Walter Korn’s Preface to the eighth edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1952), i.e. from pages v-vi:

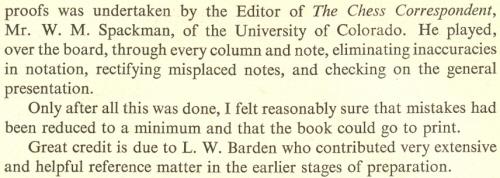

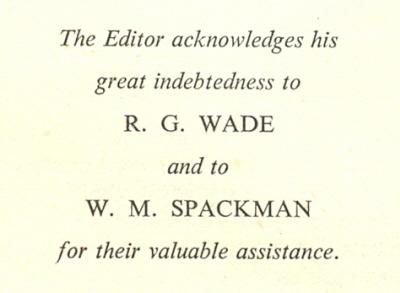

The following page had this acknowledgement:

The ninth edition (‘completely revised by Walter Korn and John W. Collins’) was published in 1957. In referring to earlier editions, Korn’s Preface (pages v-vi) made no mention of Wade, stating ‘... the eighth edition was both directed and revised by me’. On page iii of the Preface to the tenth edition (London, 1965) this became ‘... the eighth edition was both directed and solely revised by me’. On page v of the eleventh edition (London, 1972) Korn’s Preface stated, ‘I subsequently also directed and revised the eighth edition’.

Shortly after the eighth edition appeared, CHESS (August 1952, page 214) published a review which included the following:

‘W. Korn claims, on the dust-cover, to be an international master. There is no master on the official FIDE list named Korn. Is Korn an assumed name? We cannot recall seeing his name in any international tournament since we have known him as W. Korn. When we peruse the sections which he acknowledges were done by R.G. Wade, we note a contrast. Wade is willing and able to dogmatize, he is interested in the chess, reveals clearly the various systems and passes the judgments we want ... It seems clear that the last word in MCO should always come from a practising master ...

Wade’s work on the French, Caro-Kann, Sicilian, Queen’s, etc., though already a little out of date (most of it was finished three years ago and it has obviously been hardly touched since) is the best he has ever done, and a lasting contribution to chess literature. It is not only better than the rest, it is better than most that has appeared in MCO before.’

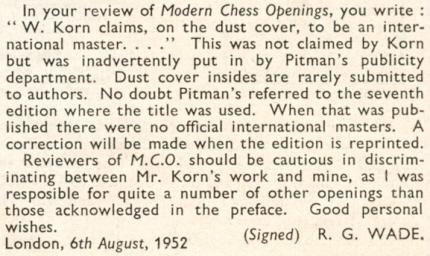

Wade wrote on page 236 of the September 1952 CHESS:

From the dust-jacket of America’s Chess Heritage by Walter Korn (New York, 1978):

(7300)

Leonard Barden writes:

‘The mild tone of Bob Wade’s August 1952 letter to CHESS which you reproduced in C.N. 7300 suggests that he had not completely given up on Walter Korn by then and that his hostility grew later.

Korn asked me to be the reviser for the tenth edition of Modern Chess Openings in 1962 or 1963, for a flat fee of about £1,000. Conscious of what Wade had told me, I haggled and asked for firm payment guarantees. The negotiations broke down, and Korn turned to Larry Evans. I should add that as an active grandmaster he did a better job than I, as a pure theoretician, would have done.

At the time when Korn was appointed editor of Modern Chess Openings, there was a widespread feeling among leading players and writers that his credentials (a few theoretical articles in the BCM) did not justify his acquiring the rights to Modern Chess Openings from the ageing Richard Griffith.’

(7321)

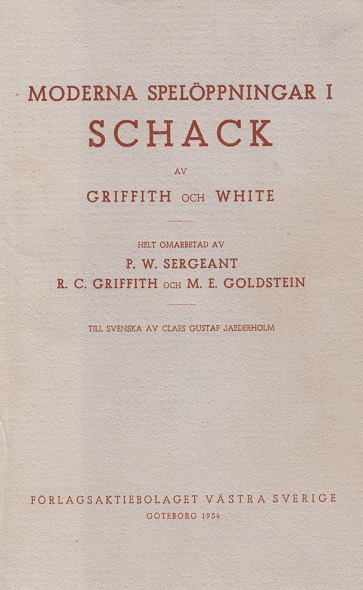

In 1952 Walter Korn brought out the eighth edition of Modern Chess Openings. A year or two later, bizarrely, a company in Göteborg published a Swedish translation of the fifth edition, which had been written back in 1932, by P.W. Sergeant, R.C. Griffith and M.E. Goldstein. The Swedish book had 1954 on the dust-jacket and 1953 on the title page and imprint page.

(10142)

In our feature article on William Winter:

From page 226 of CHESS, July 1946:

The concluding reference to Modern Chess Openings is an error.

An extract from C.N. 8303 concerning the The ‘Magnus Smith Trap’:

Annotating the game Lawrence v Fox in the United States v Great Britain cable match, Hermann Helms wrote on page 1 of the sports section of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 May 1911 and on page 129 of the June 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Evidently leading up to the Magnus Smith variation, which continues as follows: 6 B-QB4 P-KKt3 7 KtxKt PxKt 8 P-K5 Kt-Kt5 9 B-B4 P-Q4 10 KtxQP PxKt 11 BxP, etc. The subsequent play, which yields a win for White, was analyzed exhaustively by Mr Smith in the March number of the American Chess Bulletin.’

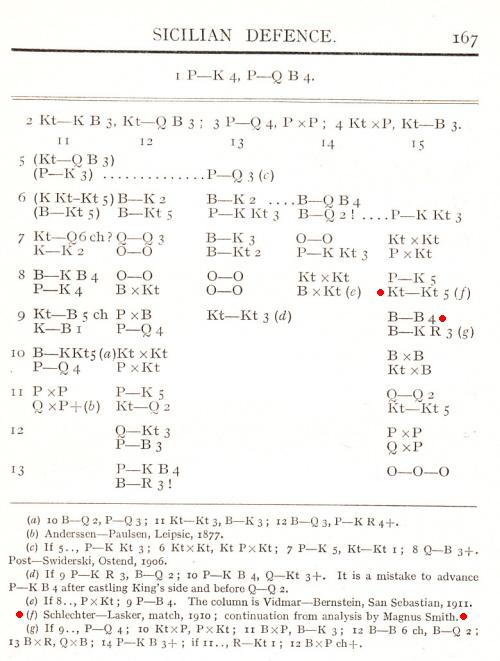

Magnus Smith was mentioned for 9 Bf4 on page 167 of Modern Chess Openings by R.C. Griffith and J.H. White (London, 1913):

On page 29 of the November 1995 Chess Life Edmar Mednis referred to 1 d4 Nf6 2 Bg5 as the ‘Trompowsky-Ruth Attack’, whereas on page 290 of Chess Thinking (New York, 1995) Bruce Pandolfini called it the ‘Ruth-Trompowsky Attack’. Editions of Modern Chess Openings have presented a range of contradictory information, and page 441 of the 13th edition (London, 1990), edited by Walter Korn and revised by Nick de Firmian, introduced another player as a ‘co-author’ of the opening:

‘The Trompowski Attack was co-authored by Opočenský (along with Trompowski) in the 1930s, but long before them it was consistently propagated by the American W.A. Ruth.’

The passage thus also introduced another verb, ‘propagate’, to join ‘popularize’ and ‘promulgate’ as descriptions of Ruth’s activity with 1 d4 Nf6 2 Bg5, but where are the hard facts?

(8732)

A remark by Imre König about Leonard Barden in a report on the 1949 British championship in Felixstowe:

‘Barden’s knowledge of theory is extraordinary, he is a walking compendium of MCO and Bilguer.’

Source: BCM: September 1949, page 312.

After quoting this on page 282 of the 1 December 1949 Chess World, C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘Understatement! He is years ahead of the latest editions of both. Barden is 20 – a modern history student at Oxford.’

(9348)

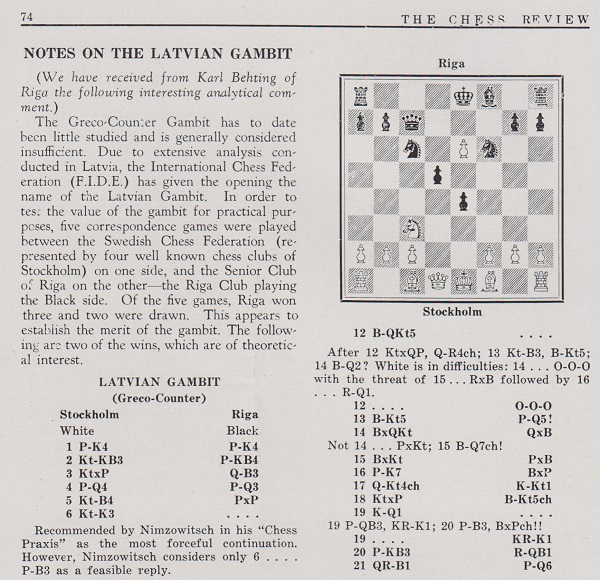

The start of an article on pages 74-75 of the Chess Review, April 1937:

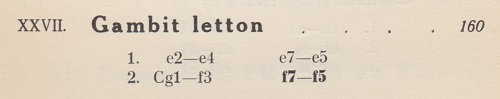

The name ‘Latvian Gambit’ had been officially adopted by FIDE several years earlier, in its publication discussed in C.N. 3902 and 10058, Débuts du jeu d’échecs (Prague, 1934). From page 35:

From page 81 of the sixth edition of Modern Chess Openings (Philadelphia, 1939):

‘... Greco’s Counter-Gambit has been given a new lease of life by the researches of Latvian analysts (particularly K. Behting), who maintain that the gambit is perfectly sound. Their analysis seems to be quite correct, but in practical play by Black usually loses.’

The earliest edition of Modern Chess Openings to include the specific term ‘Latvian Gambit’ was the seventh (London, 1946). From page 102:

‘The Greco Counter (now called Latvian) Gambit.’

Even so, in English-language sources the names remained more or less interchangeable. For instance, the May 1968 CHESS (pages 244-251) and the end-May 1968 issue (pages 281-284) had an ‘amazing article’ on 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f5 by B. Simm (‘Simms’ in the heading to the first part). The two parts were entitled, respectively, ‘The Latvian Gambit (alias Greco Counter-Gambit)’ and ‘The Latvian or Greco Counter-Gambit’.

To what extent modern theoreticians give due attention to old analysis is an uncomfortable question. To mention a couple of sources at random, there was a large amount of material, mainly by Stasch Mlotkowski, on the ‘Greco Counter-Gambit’ in the BCM in 1915-16, and a two-part article entitled ‘Zum Lettischen Gambit’ by Walter Henneberger was published in the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, January 1941, pages 6-9, and February 1941, pages 21-23.

(10123)

The opening was also discussed in C.N. 10122.

The start of an entry, by W.R. Hartston, on page 111 of The Encyclopedia of Chess edited by Harry Golombek (London, 1977):

The description ‘a gift of the gods to a languishing chess world’ is often said to have been written ‘once’ by someone, but what are the particulars?

The question was raised by Leonard Reitstein on page 197 of the July 1965 BCM, in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column, but the only source offered was page 6 of the ninth edition of Modern Chess Openings by Walter Korn and John W. Collins (London, 1957):

(11255)

See also The Evans Gambit.

In the introduction to the 8 April 1973 Sunday Times column, C.H.O’D. Alexander gave some general observations on postal play:

‘Though much correspondence play, even at international level, is surprisingly bad, playing C.C. makes one realize that chess is difficult; I can take as much time as I like and still get it wrong. Apart from oversights (you make those after two hours’ thought as well as after two minutes’) there are three causes of failure. First, inadequate opening knowledge; how many innocents come to grief through trustingly following MCO on the assumption that it must be right. Next lack of imagination – you simply fail to see a possible line. Most important, faulty judgement; one weighs up positions wrongly.’

(12068)

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.