Edward Winter

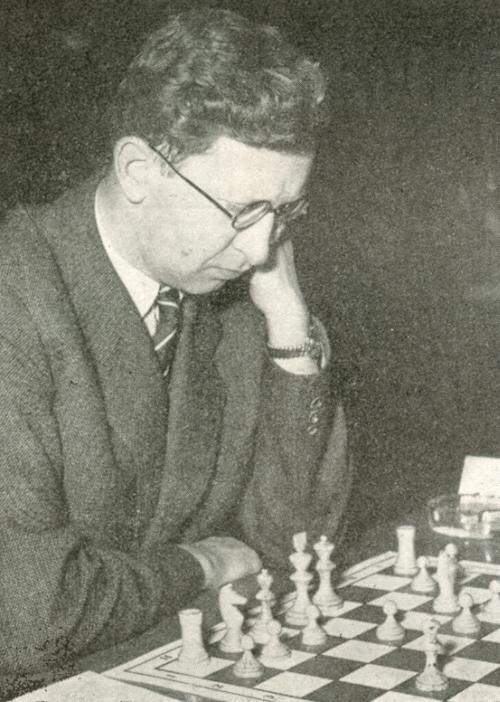

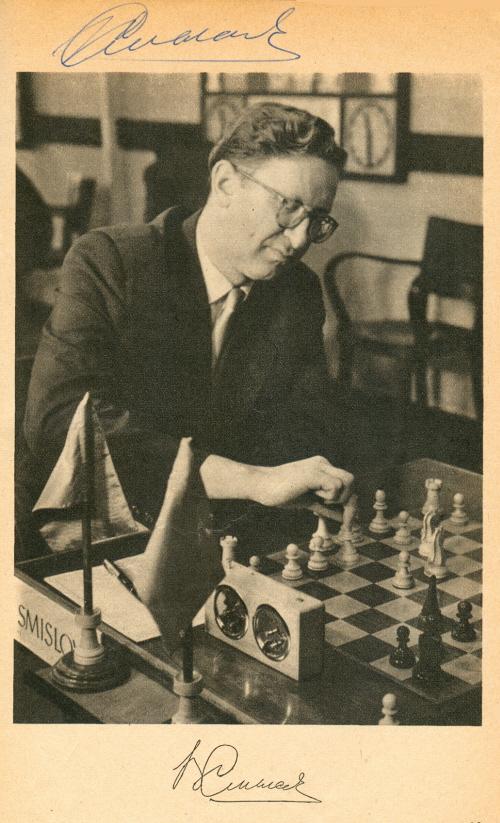

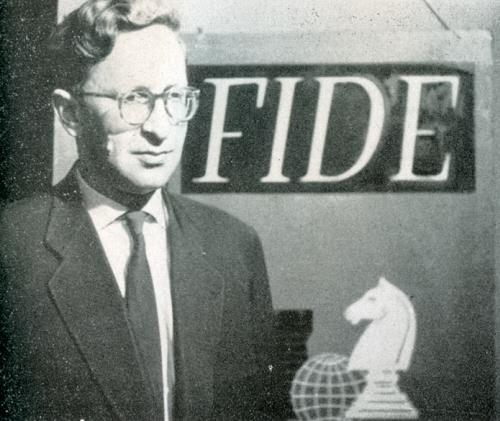

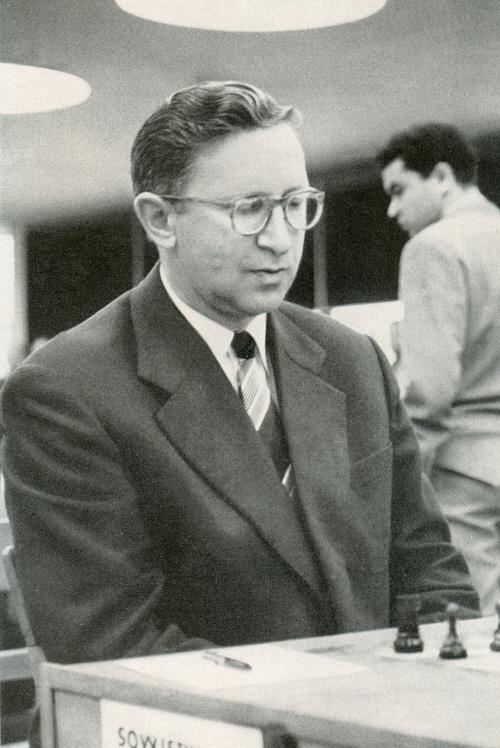

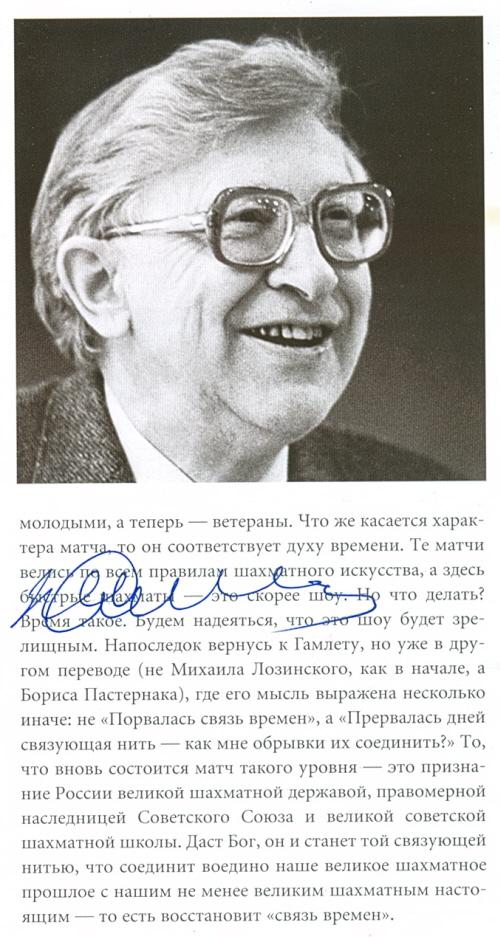

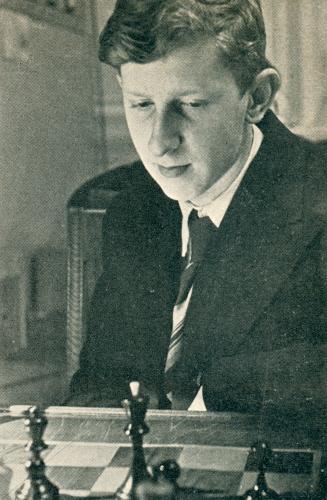

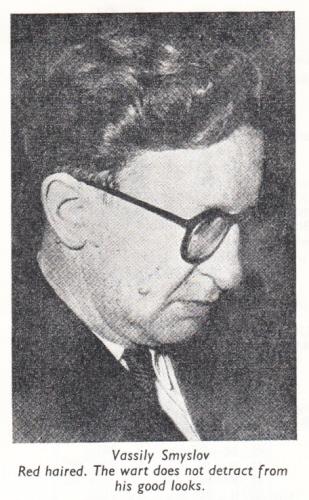

We present a selection of photographs of Vassily Smyslov:

Source: Chess Review, February 1944, page 7

Source: Chess Review, June-July 1944, page 4

Source: Chess in Russia by P. Romanovsky, opposite page 26 (London, 1946).

Source: Chess Review, front cover, April 1958.

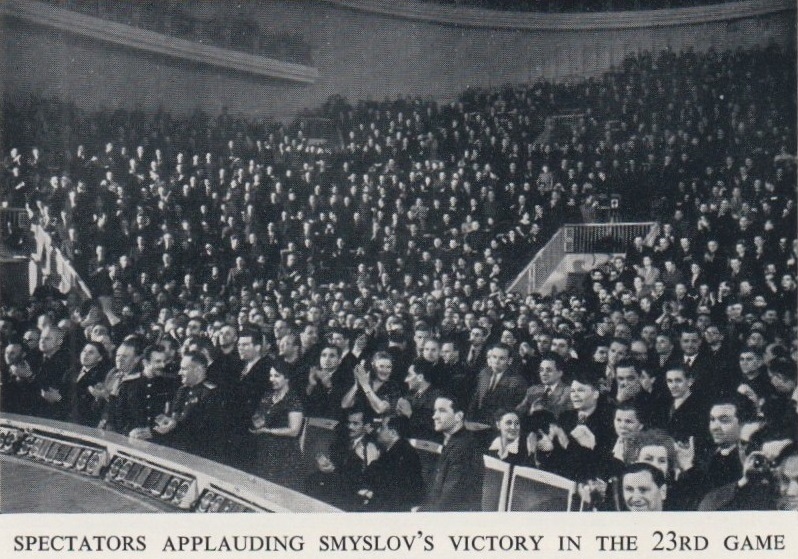

Source: Kandidatenturnier für Schachweltmeisterschaft by S. Gligorić and V. Ragozin, page 39 (Belgrade, 1960).

Source: Programme, Russia v Rest of the World tournament, 2002, page 7.

(6512)

Those who believe that there is hardly any chess book by a world champion that does not deserve to appear in an English edition will be pleased to see that Pergamon Press have published a translation (almost inevitably by K.P. Neat) of Smyslov's ‘In Search of Harmony’.

The English title, 125 Selected Games, highlights the fact that the emphasis is on actual play rather than autobiography. Smyslov seems to tire easily of writing about himself, and the opening chapter ‘My Chess Career’ is over just as one thinks it is about to begin. However, we pick the following interesting extracts from it:

‘In my opinion, the style of a player should not be formed under the influence of any single great master.’ (Page 4)

‘In chess I am also a staunch supporter of classical clarity of thought. The content of a game should be a search for truth, and victory a demonstration of its rightness. No fantasy, however rich, no technique, however masterly, no penetration into the psychology of the opponent, however deep, can make a chess game a work of art if these qualities do not lead to the main goal – the search for truth.’ (Page 5)

Then follow the 125 games. How does Smyslov rate as an annotator of his best efforts? Alas, our answer has to be a reluctant ‘not very impressively’. To be sure, his notes are bone-dry and impersonal, but their real fault is graver: surely the minimum that can be expected of the notes to any decisive game is an indication of the loser’s errors, yet it is precisely this that Smyslov repeatedly fails to provide.

Some examples; Game 4 (v Veresov) has no criticism of the loser’s play. Game 5 (v Boleslavsky) contains a remark that 9...Bd7 ‘was preferable’ to 9...c4, but no other censure of Black’s play. It is hard to believe that Smyslov wishes to suggest that 9...c4 was the losing move, but if not where exactly did Black’s game slip away? The former world champion wins game 9 (v Kamishov) in just 17 moves, yet the fact that no objection is raised to any of Black’s moves might lead some to assume quite wrongly that the Latvian Gambit is therefore simply refuted. In game 19 Petrosian (White) loses, but Smyslov again fails to point out any improvements. One could go through the book like this.

The other disappointing aspect of Smyslov’s annotational style relates to his own play: there are barely a handful of occasions when he admits to error himself. Even world champions’ play can generally be improved upon at at least one stage per game, but Smyslov closes his eyes to this. The combination of insufficient criticism of both the winner’s and the loser’s moves gives the impression – no doubt quite unintentional – that Smyslov’s victories are pre-destined, and as a consequence the whole balance of our appreciation of his artistry is put in jeopardy.

Despite its failings, 125 Selected Games stands as one of the most important chess books to be published in the English language this year [1983]. We obtained the impression that in his choice of games Smyslov was deliberately going for the most overtly combinative of his successes, as though feeling that this side of his achievements has been too often overlooked in assessments of his career. Whatever, the range of games is unquestionably of exceptional interest, as befits one of the most naturally gifted players of the post-War period.

(502)

The Game of the Round (published by Chequers) is a 320-page work on the 1986 Dubai Olympiad, similar in style to the same publisher’s world championship book (C.N. 1285). As before, a team of writers has joined forces to produce, with notable speed, a fine record of a memorable event. One stylistic complaint, though: ‘I’ and ‘we’ are often used without any indication of who is writing.

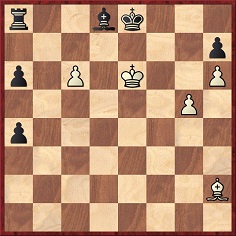

Instead of a game from the tournament, here is one of three compositions (two by Smyslov) given on page 63:

‘On 29 November former world champion Vassily Smyslov composed an endgame study with a strikingly original theme:

White to play and win

1 g6 hxg6 2 h7 Bf6 3 Bb8!! (If 3 Kxf6 O-O-O!) 3...Rxb8 4 Kxf6 Kd8 5 h8(Q)+ Kc7 6 Qh2+ wins.’

(1376)

Having noted that on page 272 of the June 1987 BCM David Friedgood gave a correction (saying that the pawn on a4 should be black), we asked John Roycroft, the Editor of EG, if he could clarify matters. He tells us that Mr Friedgood made the change purely on grounds of soundness; with a white pawn at a4 the study is unsound because the O-O-O variation does not save Black. With a black pawn at a4 all appears correct.

Where was Smyslov’s study first published, and what was the exact position?

(1564)

From Paul Lamford (Sutton Coldfield, England):

‘This was first published, as far as I am aware, in Dubai Olympiad Bulletin 14, page 5, and the original position was the same as that in the BCM, April 1987, page 174, except that the pawn at a4 was black. The Game of the Round (a Chequers Chess Publication) states on page 63 that ‘On 29 November former world champion Vassily Smyslov composed an endgame study ...’, but gives the position wrongly with a white pawn on a4. I reproduced this error, which renders the study unsound, in the studies column in the April 1987 BCM and I gave the correction, which David Friedgood pointed out, in the June issue, page 272.’

(1615)

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) draws our attention to pages 723-724 of the January 1990 issue of EG, where the (correct) position was introduced as follows:

‘This was composed at the Dubai Olympiad, where for the first time Smyslov was present neither as participant nor trainer. He helped Bob Wade produce the daily bulletin – and had time to compose.’

Our correspondent has also supplied a feature on page 4 of the 6/1987 issue of the Bulletin of the Central Chess Club of the USSR:

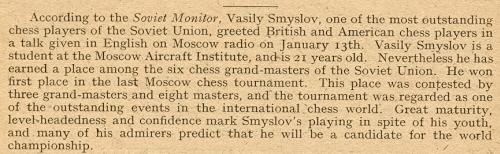

C.N. 2484 (see page 144 of A Chess Omnibus) quoted from page 32 of the February 1943 BCM:

‘Vasily Smyslov is a student at the Moscow Aircraft Institute, and is 21 years old. Nevertheless he has earned a place among the six chess grand-masters of the Soviet Union. … Great maturity, level headedness and confidence mark Smyslov’s playing in spite of his youth, and many of his admirers predict that he will be a candidate for the world championship.’

Below is the magazine’s complete item:

This photograph of Smyslov comes from page 151 of the May 1943 Chess Review:

(6516)

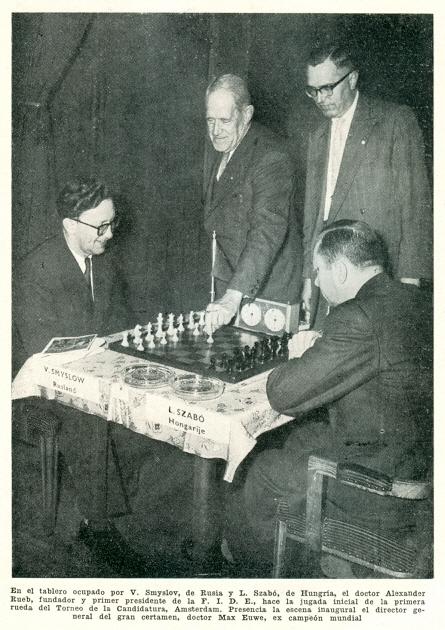

This photograph of V. Smyslov, A. Rueb, M. Euwe and L. Szabó at the 1956 Candidates’ tournament in the Netherlands is taken from page 161 of the May 1956 issue of Ajedrez (Buenos Aires):

(5377)

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) raises the subject of the first published game by Smyslov.

Game one in Smyslov’s book 125 Selected Games (Oxford, 1983) was his win as Black against Gerasimov (‘Championship of the Moskvoretsky House of Pioneers, Moscow, 1935’), and his concluding remark (page 20) was:

‘This was my first tournament game to appear in print (in the newspaper 64)’

If a reader has that issue of 64 and can provide a copy of the Smyslov game, we shall gladly reproduce it here.

(6531)

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) has submitted Smyslov’s game against Gerasimov (Moscow, 1935), as published on page 3 of the 29 February 1936 issue of 64:

Our correspondent notes that the brilliancy, annotated by Fedor Lvovich Fogelevich (1909-41), was presented as if Smyslov were White.

It became a famous game. See, for instance, pages 176-177 of The Chess Companion by I. Chernev (New York, 1968).

(6537)

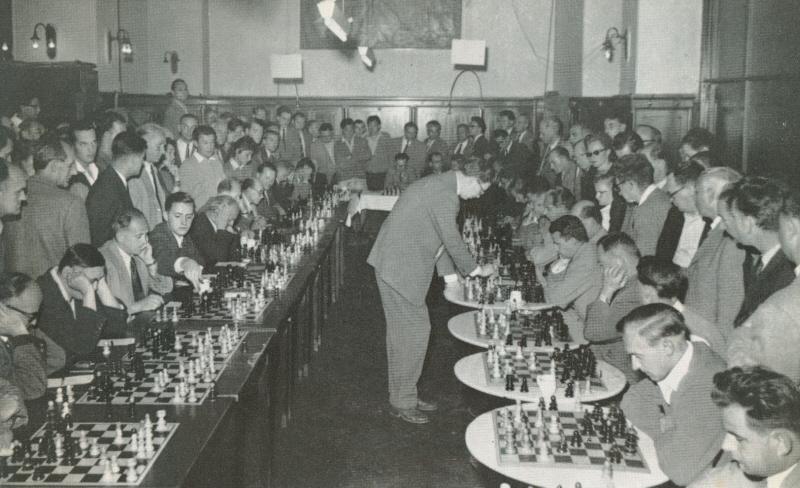

The photograph below (taken in Vienna in 1957) was published opposite page 81 of Chess A Beginner’s Guide by Stanley Morrison (Guildford and London, 1968):

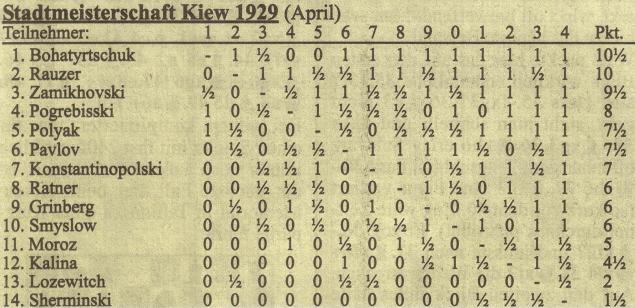

Thomas Binder (Berlin) notes that an article about Bohatirchuk on pages 70-71 of the 6/2008 Rochade Europa includes this crosstable:

Our correspondent asks about the identity of the player who finished tenth.

Is it definitely established that he was Vassily Ossipovich Smyslov (1881-1943), the future world champion’s father? Pages 1-3 of 125 Selected Games by V. Smyslov (Oxford, 1983) featured reminiscences of early family life and included his father’s victory over Alekhine at St Petersburg, 1912. We should welcome further games played by Smyslov senior.

(5606)

From Andrey Terekhov (Singapore):

‘I have found another crosstable which mentions Smyslov of Kiev, published in the 8/1945 issue of Shakhmaty v SSSR in an article about the All-Union tournaments of first-category players. That year there were four semi-finals in different cities of the USSR. The crosstable of the Tallinn tournament (published on page 233) included Smyslov (of Kiev), who scored 6½/15 and shared 10-12th places. The article also gave, on page 234, a game which “Smyslov of Kiev” lost in that tournament to Serebriyskiy (of Kharkov):

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 Nc6 4 Ngf3 Nf6 5 e5 Nd7 6 c3 f6 7 exf6 Qxf6 8 Bb5 Bd6 9 Qe2 O-O 10 Nf1 e5 11 Bxc6 bxc6 12 dxe5 Nxe5 13 Nxe5 Bxe5 14 Bd2 a5 15 O-O-O Ba6 16 Qe1 a4 17 a3 Rab8 18 Ne3 Bd6 19 f3 Bxa3 20 bxa3 Bd3 21 Nc2 Bxc2 22 White resigns.

A player named Smyslov was also mentioned on the last page of the 13/1937 issue of the Ukrainian-language newspaper Shahist in a brief report on the semi-finals of that year’s Kiev championship:

The semi-finals comprised three groups of 12 players, and the top players in each group qualified for the final. A player named Smyslov was in the second group, but he did not finish among the top four and thereby qualify.

The following chronology is offered tentatively to suggest that Smyslov of Kiev and Vassily Ossipovich Smyslov were different people:

- Vassily Ossipovich Smyslov studied in St Petersburg and began working there in the “Expeditsiya po zagotovleniyu zennyh bumag”;

- He played in a number of tournaments in the early twentieth century;

- After the 1917 Revolution the organization where he worked was renamed “Goznak” and was transferred to Moscow. Vassily Ossipovich Smyslov moved to Moscow;

- Vassily Vassilievich Smyslov was born in Moscow in 1921;

- Somebody named “Smyslov” played in the Kiev championship in 1929 and in the semi-finals of the 1937 Kiev championship;

- Vassily Ossipovich Smyslov died in 1943. (This, together with the above information about him, is taken from V.V. Smyslov’s book Letopis shakhmatnovo tvorchestva (Moscow, 1993);

- “Smyslov of Kiev” played in a tournament in 1945.’

(10098)

Further information has been received from Dmitriy Komendenko (St Petersburg, Russia):

‘Looking at the rusbase website I have found that a player named Smyslov played in the championship of Kiev at least three times: 1929, 1930 and 1936. Only his surname is given, with no forename or patronymic, but I did find a reference to a Victor Victorovich Smyslov on a Russian website. Before it went offline I took this screen-shot:

The text states that he was born in 1909 and worked at the КИСИ (Киевский инженерно-строительный институт), and his interest in chess is mentioned.

In 1936 the Ukrainian chess newspaper Шахіст had further information about the little-known Smyslov from Kiev, including a photograph and the fact that he was a second-category player:

Шахіст issue 3, 25 October 1936, page 1

Шахіст issue 6, 25 November 1936, page 2

The website of the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture has another photograph of Smyslov, clearly the same person as shown in Шахiст. It is also noted that he studied in Kiev from 1927 to 1931, moved to Moscow and returned to Kiev in 1936.’

(11952)

Another example of the quirkiness of CHESS, from page 73 of the 8 September 1956 issue:

<

<(8156)

Andrey Terekhov forwards a news item on page 4 of the 48/1936 issue of 64:

This report on a Kiev-Moscow schoolchildren’s match mentions Smyslov as a composer of chess studies published not only nationally but also abroad. Our correspondent asks whether 64 was correct and, if so, where Smyslov’s compositions were published outside the Soviet Union in or before 1936.

(10541)

With Stephen Fry’s permission we quote from his article ‘Giving the Smyslov Screw a theatrical twist’ which appeared in the Daily Telegraph, 26 October 1990, page 21:

‘My own theory, and I cannot emphasize its worthlessness enough, is that chess is fundamentally a theatrical affair. I first became really interested in the game when I heard about the Smyslov Screw. There was a great Russian world champion, who recently enjoyed something of an Indian summer, called Vassily Smyslov, particularly noted as a master of the endgame. Whenever he moved a piece from one square on to another he had a habit of twisting it, as if screwing it into the surface of the board.

Others might drop their man lightly or bang it aggressively, Smyslov gently screwed it in. The psychological effect of such a move can be devastating. It looks so permanent, so deliberate, so absolutely assured. Kasparov hunches himself over the game, in a brooding, minatory and virile manner that is worth at least three extra pawns.’

(4275)

What more is known about the ‘Smyslov Screw’ referred to by Stephen Fry (C.N. 4275)? Given that we recalled a 1970s Master Game television programme (BBC) in which the commentator, Leonard Barden, referred to Smyslov’s way of handling pieces (albeit deft captures in a single sweep, we thought, rather than screwing pieces into the board), we raised the matter with Mr Barden. He has replied as follows:

‘I’m sure I said it or wrote it in more than one place, and I was referring to the placing of Smyslov’s own piece as well as a capture of his opponent’s. I think many grandmasters have acquired the technique of a brusque swooping action when capturing. But my memory is that the original observation was made by Hugh Alexander, probably after his defeat by Smyslov in the Britain v Soviet Union match of summer 1954. Alexander also remarked on Botvinnik’s habit of writing his move down with careful precision, so that the opponent felt like resigning at move one. In 1960 I had the privilege of 14 blitz games with Robert Fischer when he visited my house. I lost 1½-12½, which I thought a good result for me, and was physically overawed, as were others, by Fischer’s large hands and talon-like capturing mannerism. So on more than one occasion, which doubtless included The Master Game, I brought these three cases together, with others, as examples of how lesser lights were subliminally intimidated by the greatest masters. I could well have said something like this, too, in the BBC Network Three radio chess programmes which antedated The Master Game by a decade. Later, of course, the technique moved to a more sophisticated level with Kasparov’s bombardment by thought waves ...’

(4292)

David Picken (Greasby, England) quotes the following from pages 47-48 of World Chess Championship 1954 by Harry Golombek (London, 1954):

‘Watching them today I was struck by the contrast between the players in their actual physical moving of the pieces. Smyslov invariably makes each move with a little flourish and a motion, as though he were screwing in each piece on the board. Botvinnik is strictly utilitarian in his methods. He shuffles the pieces into position almost negligently, as though he knows they will drop into the right place given the slightest encouragement – and so, it must be admitted, they usually do.’

(4298)

Jonathan Hinton (East Horsley, England) points out the following paragraph on page 197 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974):

‘“The Screw” – Screw the piece firmly into the square. This gives the impression of great scientific solidity. Practiced by World Champion Smyslov.’

(4365)

The photograph below comes from opposite page 63 of World Chess Championship 1954 by Golombek:

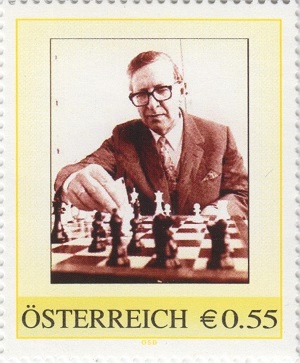

C.N.s 3680, 3681, 3689 and 9904 (see Chess and Postage Stamps) showed Austrian stamps featuring Alekhine, Capablanca, Fischer, Kasparov, Rubinstein and Mieses.

We have a few others, including portraits of Steinitz, Lasker and Smyslov:

(10545)

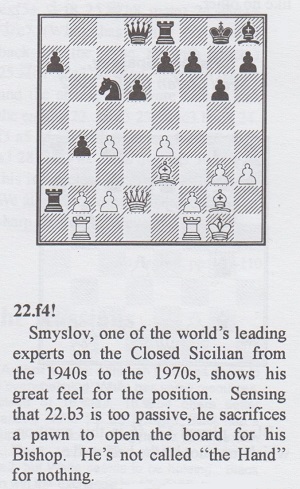

Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) notes a remark by Spassky in an interview on page 23 of the Autumn 1998 Kingpin:

‘Smyslov is a chess player with a fantastic intuition. I call him “Hand” because his hand knows exactly on which square to put which piece at a given moment; actually, he does not have to calculate anything.’

Our correspondent asks whether earlier occurrences of the term are known.

He adds this slightly later citation from page 155 of The Unknown Bobby Fischer by John Donaldson and Eric Tangborn (Seattle, 1999):

For observations on the physical appearance of Smyslov’s hands see page 57 of Chess Duels by Yasser Seirawan (London, 2010).

Andrey Terekhov (Singapore) forwards this picture of Vassily Smyslov:

Our correspondent reports that the reverse of the (undated) photograph states that it was taken in Sweden.

From page 104 of the November-December 1940 American Chess Bulletin, in a report on that year’s USSR championship in Moscow:

‘The play of the youthful Smyslov is of unusual profundity, originality and versatility. He invites complications and preferably selects difficult systems of defense. When opportunity offers, he is capable of giving a display of fireworks on the chessboard.’

(10758)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘The Swiss Federal Archives have some rare chess footage, including an 84-second segment on the last round and prize ceremony of the Candidates’ tournament in Switzerland on 23 October 1953. It features, among others, Bronstein, Keres, Reshevsky, Smyslov and Taimanov.’

Mark Taimanov and Samuel Reshevsky

Vassily Smyslov

(10905)

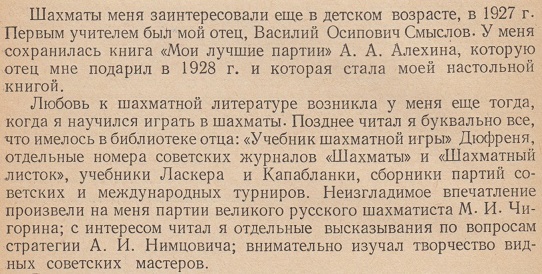

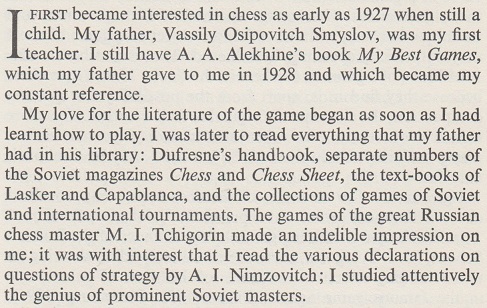

David Prabitz (Graz, Austria) notes Vassily Smyslov’s slightly different accounts (i.e. with ‘father’ and ‘uncle’) of the first chess book that he was given as a child. Below are the Russian and English texts in three autobiographical works:

Избранные партии (Moscow, 1952), page 16

My Best Games of Chess 1935-1957 (London, 1958), page xxxiii

В поисках гармонии (Moscow, 1979), page 5

125 Selected Games (Oxford, 1983), page 1

Летопись шахматного творчества (Moscow, 1993), page 7

Smyslov’s Best Games, volume one (Olomouc, 2003), page 5.

The first English translation was by P.H. Clarke, and the other two were by Kenneth P. Neat.

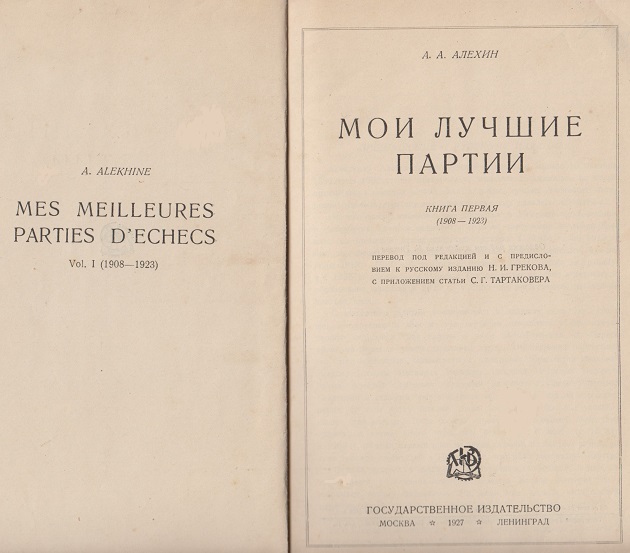

The Russian translation of Alekhine’s first Best Games volume was published in 1927, mentioning a print-run of 5,000 copies. The second edition (1928) stated that 7,000 copies were printed.

Notwithstanding the text opposite the title page, Alekhine’s book did not appear in French until 1936 and was not entitled Mes meilleures parties d’échecs. See C.N.s 4436 and 4439.

(11385)

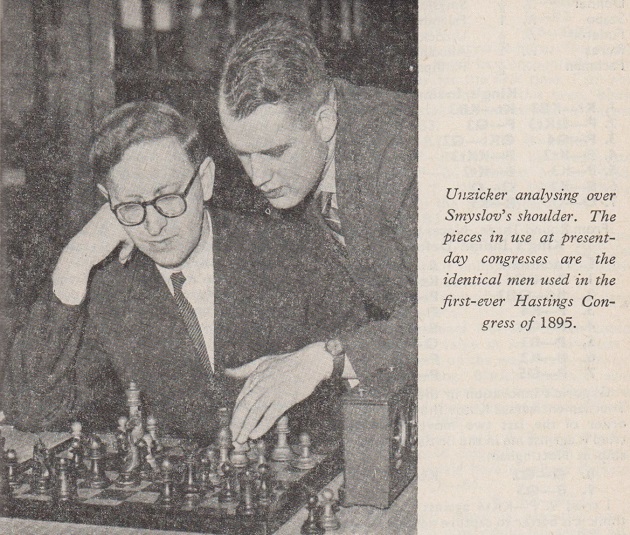

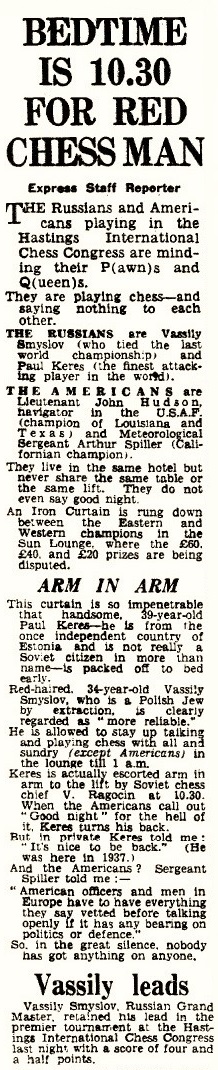

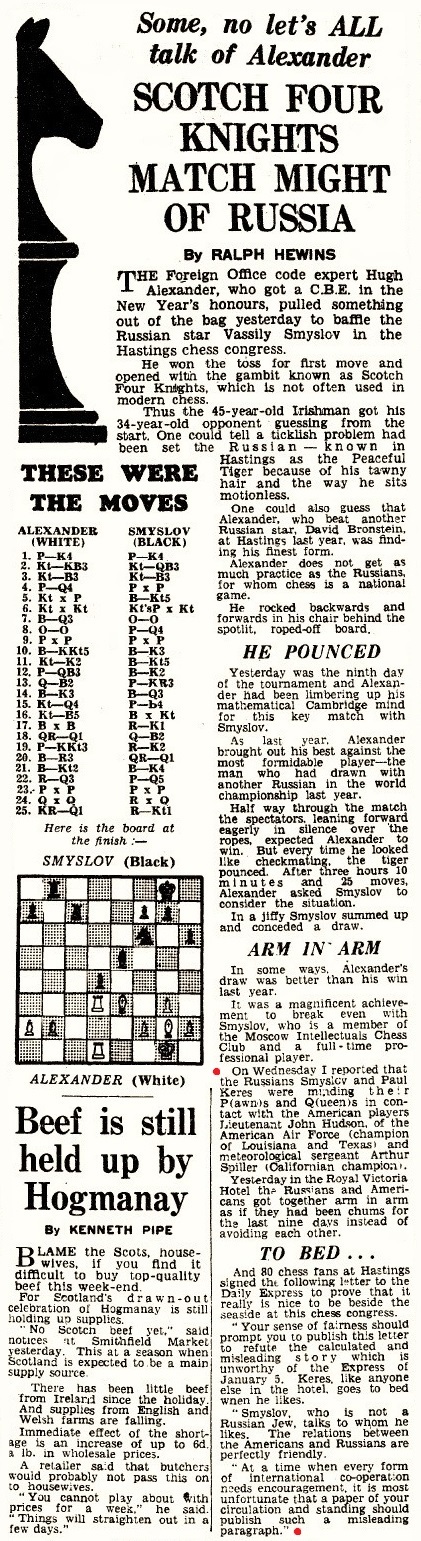

Olimpiu G. Urcan has obtained permission from the Keystone Pictures archives for two photographs of Vassily Smyslov (Hastings, 1954-55) to be reproduced here:

Another shot of Smyslov and Unzicker was on page 169 of CHESS, 8 January 1955:

Page 184 of the 22 January 1955 issue of CHESS had an account of these press reports by Ralph Hewins:

Daily Express, 5 January 1955, page 5

Daily Express, 7 January 1955, page 5.

J. Hudson and A. Spiller participated, respectively, in the Major Section, Premier Reserves and in the Premier Reserves ‘A’, each obtaining 3½ points (BCM, February 1955, page 69).

(11390)

Addition on 17 January 2025:

Reproduced with permission from the Hulton Archive, the above informal shot of C.H.O’D. Alexander and V. Smyslov was taken at the Caxton Hall, London on 3 July 1954. A two-round Anglo-Soviet match took place on 3 and 5 July.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.