Edward Winter

In both cases the player of the ‘weak’ move lost the game.

Tarrasch’s move 3 Nd2 in the French Defence had been seen in play before Tarrasch himself (born 1862) introduced it. The Illustrated London News of 7 March 1874 gave a game between G.B. Fraser and H.M. Stirling which began 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 c5 4 c3 Nc6 5 Ngf3 Qb6. Staunton in his notes calls 3 Nd2 ‘a novelty not undeserving attention’ but recommends 5...Nf6 instead of 5...Qb6.

(43)

From page 48 of Evans on Chess by Larry

Evans (New York, 1974):

‘The “lapsus manus” variation derives its name from a slip of the hand made by world champion Alexander Alekhine in defense of his title.

Alekhine v Euwe, 5th match game 1935: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Ne2!? dxe4. Alekhine unintentionally moved his knight, sacrificing a pawn; but it turned out to be playable after 5 a3, and a new line was born.’

In fact, the ‘new line’ was already familiar, not to say famous. Alekhine played 4 Ne2 in his celebrated miniature against Nimzowitsch at Bled, 1931 – see page 94 of the second volume of his best games. There is no reason to believe it was a slip of the hand on either occasion.

Mr Evans is no doubt thinking of 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Bd2 (Alekhine-Flohr, Nottingham, 1936), which Alekhine admitted, on page 17 of the tournament book, was a ‘lapsus manus’.

(1598)

Alekhine’s note to 4 Bd2:

‘A “lapsus manus”. I intended to play 4 P-K5 and P-B4, as, for instance, against Nimzowitsch at San Remo, 1930, but instead I made the move with the bishop first.’

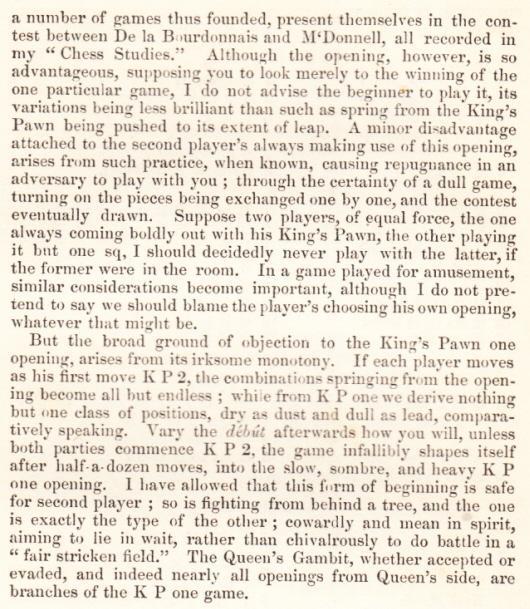

‘… that slowest of encounters, the execrable French Defence – “King’s Pawn one sneak”, as Walker omits no opportunity of stigmatizing it; or “King to Pawn’s one”, as Leonard used derisively to style it.’

From page ix of Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by Miron J. Hazeltine (New York, 1866).

(2253)

To help redress the balance, here is the view on 1…e6 expressed by Daniel Harrwitz on page 27 of his Lehrbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1862):

‘This is the best game for the second player because he is exposed to no attack, and in a few moves the game is level.’

(2340)

Further support for the French Defence comes from John Cochrane on page 260 of A Treatise on the Game of Chess (London, 1822):

‘I now proceed to the consideration of a game which has been hastily passed over as bad by almost every writer on chess; say hastily, because they have evidently not given it that attention which its intricacy undoubtedly deserves: it is a game entirely of position, and, consequently, one of extreme difficulty. The attack, which is thrown into the hands of the second player, when the first endeavours to maintain his king’s and queen’s pawns in the centre, is a singular feature in it.’

On the next seven pages Cochrane analysed four lines, mainly beginning 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 c5. It was not until the next decade that the name ‘French Defence’ was introduced; Cochrane called it the ‘King’s pawn one game’.

(2390)

C.N. 2253 (see above) quoted from page ix of Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by Miron J. Hazeltine (New York, 1866):

‘... that slowest of encounters, the execrable French Defence – “King’s Pawn one sneak”, as Walker omits no opportunity of stigmatizing it; or “King to Pawn’s one”, as Leonard used derisively to style it.’

George Walker did indeed dislike the French Defence. The following comes from pages 125-126 of his book The Art of Chess-Play: A New Treatise on the Game of Chess (London, 1846):

In Walker’s column in Bell’s Life in London the word ‘sneak’ was often used, though with reference to a variety of openings (including the Sicilian Defence) in which Black avoided an open game:

(8368)

C.N. 8368 quoted a passage from page ix of Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by Miron J. Hazeltine (New York, 1866):

In an apparent mix-up, the ‘sneak’ reference was attributed to James A. Leonard in item 214 of unit three of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play by W.E. Napier (New York, 1935):

‘It was the gifted Leonard, with the “first refusal” of Morphy’s mantle in his pocket, who in this country first spoke of the French Defense as the King’s Pawn Sneaks One. The obloquy of evading open-game amounted, in Civil War days, to a class consciousness. This is not hard to understand when opening play is recalled. What became terrors later on in the Ruy López were then merely growing pains. A player then had to rely on his imagination for his devices; a pre-digested game was as rare then as an original is now.

There was no good reason, many thought, to shirk open, airy, and pelting chess.

The prejudice died hard.’

See too page 211 of Napier’s Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957), as well as Horowitz’s references to Leonard (based on Napier’s comments) on page 84 of Chess Review, March 1950 and on page 88 of How to Win in the Chess Openings (New York, 1951).

(8386)

26 November 2024:

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) sends the following extract from Le Sport (7 August 1861), page 3, where Saint-Amant was commenting on the 1861 Anderssen v Kolisch match in London.

‘Les parties jouées sont belles sans doute, quoique gâtées souvent par des méprises indignes de si habiles champions. Elles trahissent, en outre, un sentiment d’appréhension mutuelle, une trop grande réserve, si mieux l’on aime. Le Pion du Roi un pas, y joue un rôle fréquent. Nous citons le fait, sans y attacher une pensée de critique, mais simplement d’observation, car nous avons assez préconisé ce début qu’on appelle la partie française, en soutenant, ce qui a pris place dans la théorie des échecs, que ce serait le seul début à adopter si l’on devait jouer aux échecs, non pas seulement sa tête, mais celle de sa femme et de ses enfants.’

Strange to say, we have yet to find a translation machine which conveys Saint-Amant’s final comment correctly, i.e. that the French Defence would be the only opening to play if the survival of one’s close family were at stake.

On page 344 of the August 1927 BCM the following game annotation appeared after 1 e4 e6 2 g3: ‘“Everything gets fianchettised nowadays”, wrote Dr Tartakower a few years ago.’ Where did that observation first appear?

(4556)

For a game which began 1 e4 e6 2 b3, see C.N. 3539. The opening 1 e4 e6 2 Nh3 occurred in C.N. 495.

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) writes:

‘There is a line in the Winawer Variation of the French Defence which is often attributed to Euwe and in some sources is called the “Euwe-Gligorić line”. It occurs after 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7:

And now 10 Kd1, instead of 10 Ne2.

I have found two games with this line which were played in 1952 and 1953, and then three games played in 1960, after which the variation became more popular, but I have traced no games by either Euwe or Gligorić.

Moreover, already in 1960 Euwe wrote on page 79 of Part VIII of his Theorie der Schach-Eröffnungen (my translation):

“Another possibility in this kind of position is 10 Kd1, but the king move seems rather too sharp in this position.”

He then gave some analysis and presented moves from two games between E. Paoli and L. Schmid played in 1953 and 1960.

On what grounds has 10 Kd1 been named after Euwe (and Gligorić)?’

(5607)

The question asked in C.N. 5607 was why, after 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7, the move 10 Kd1 is credited to Euwe (and Gligorić).

Roland Kensdale (Aberdeen, Scotland) notes that a similar, though not identical, opening was seen in Gligorić v Petrosian, Candidates’ tournament, 1959 (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Qc7 7 Qg4 f5 8 Qg3 Ne7 9 Qxg7 Rg8 10 Qxh7 cxd4 11 Kd1) and that Gligorić discussed the line on pages 270-271 of his book I Play against Pieces (London, 2002). He gave the king move an exclamation mark and wrote:

‘The only way to meet the double threat on c3 and e5 and at the same time make possible a harmonious development of White’s pieces ...’

Moreover, Ola Winfridsson (Cambridge, England) quotes Mikhail Tal’s reference to that game on page 13 of Tal-Botvinnik 1960 (Milford, 2000), in a note after 11 Kd1 in the first game of that world title match:

‘... As far as I am concerned, the only game in which I came across the move 11 Kd1 (recommended, by the way, by Max Euwe) was in the above-mentioned Gligorić-Petrosian game.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘This is not the exact same variation (the moves 7...f5 8 Qg3 have been inserted), but the position is very similar (a pawn on f5 instead of f7). Perhaps some theoretician has confused the two variations and the moves 10 Kd1 and 11 Kd1.’

Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA) points out that the Tal v Botvinnik game was annotated in the second volume of Kasparov’s Predecessors series, with this comment about 11 Kd1 on page 417 of the English edition:

‘A fantastic move, recommended in 1948 by Euwe and first tried in the game Gligorić-Petrosian (Yugoslavia Candidates 1959).’

Mr Beck mentions too that page 32 of The French Defence by S. Gligorić and W. Uhlmann (New York, 1975) attributed 10 Kd1 to Euwe, and our correspondent adds:

‘Interestingly, the Tal v Botvinnik game is also annotated in the Gligorić/Uhlmann book, but it is merely stated that 11 Kd1 “offers the best prospects”, with no mention of Euwe or the Gligorić-Petrosian game (page 118).’

We conclude with an addition of our own, given that Gligorić’s book I Play against Pieces referred (on page 270) to a game between Reshevsky and Botvinnik in the 1948 world championship and that Kasparov’s book stated, correctly, that 11 Kd1 was ‘recommended in 1948 by Euwe’. In the Reshevsky v Botvinnik game this note appeared after 8 Qg3 cxd4 on pages 200-201 of Euwe’s book Wereld-Kampioenschap Schaken 1948 (Lochem, 1948):

‘Om met Pe7 te kunnen voortzetten, welke zet thans zou falen op 9 Dg7: Tg8 10 Dh7: cd4: 11 Kd1! en Wit heeft goede aanvalskansen (11...De5: faalt op 12 Pf3 benevens 13 cd4:). In aanmerking kwam echter ook 8...Pc6.’

(5613)

From Thomas Niessen:

‘I asked in C.N. 5607 why the line 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7 10 Kd1 is often attributed to Euwe (and Gligorić). C.N. 5613 contained some further information, from you and your readers, and the conclusion seems to be that the theoreticians confused two variations.

I have now found two remarks by Enrico Paoli, one dating from 1953 and the other from 1981, which point in another direction.

On pages 29-30 of his book on Venice, 1953 Paoli annotated his game against Lothar Schmid. No comment was appended to 10 Kd1, but Schmid’s reply 10...Nd7 received an exclamation mark and was described as an excellent novelty. Previously, Paoli added, 10...Nbc6 11 f4 Bd7 12 Nf3 had been played.

In fact, only two earlier games with 10 Kd1 seem to be known (Willborg v Nyman, Stockholm, 1952 and Karaklajić v Cala, Bled, 4 June 1953), and neither featured the line 10...Nbc6 11 f4 Bd7 12 Nf3.

In the tournament book Paoli also mentioned that Euwe had analysed the 8 Qxg7 line.

On pages 84-85 of the March 1981 Deutsche Schachzeitung Paoli annotated Taruffi v Renman, Reggio Emilia 1980-81, commenting after 10 Kd1 dxc3 (in my translation):

“I remember my game with Lothar Schmid at Venice, 1953 (won by Canal), where he continued 10...Nd7. This produced a new problem (I knew only Euwe’s 10...Nbc6, which he had analysed in Schach-Archiv) ...”

There is thus now another suggestion (in addition to the one in C.N. 5613) that Euwe published analysis of the line in or before 1953. Can it be traced?’

(6316)

Thomas Niessen writes:

‘In C.N. 6316 a citation hints at the early issues of Euwe’s Schach-Archiv, and eventually I found that in the July 1952 number he suggested 10 Kd1, with an exclamation mark. He also gave some lines of play, from which Paoli took a number of moves, claiming that they had been played (see C.N. 6316).

However, I have now found that in the 7/8 1954 issue of Schach-Archiv Euwe withdrew his suggestion and noted that 10 Kd1 is “practically refuted” by the game Paoli v Schmid, Venice, 1953.

It can therefore be concluded that both the above line and the similar line discussed in C.N. 5613 were suggested by Euwe, and that only the latter has any connection with Gligorić.’

(6850)

It seems that despite all the textual tampering no edition of Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games has yet used the correct spelling McCutcheon (in connection with Game 52).

John Lindsay McCutcheon (1857-1905)

(6217)

The game is Fischer v Rossolimo, New York, 1965.

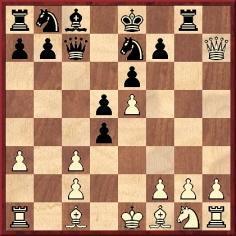

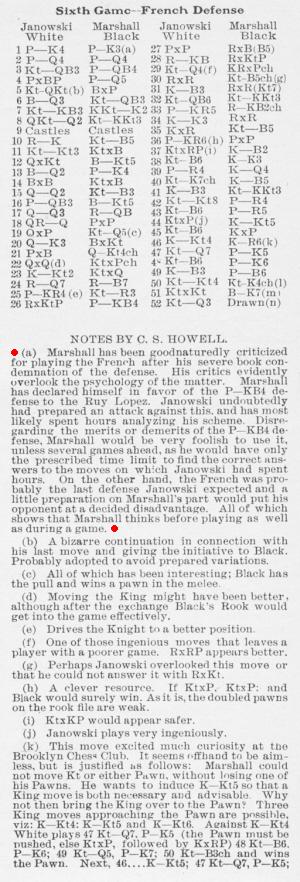

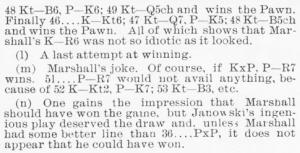

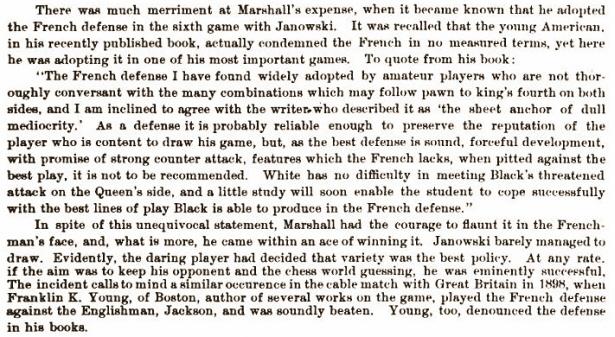

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes a case of a leading master strongly criticizing an opening shortly before playing it in an important game. Our correspondent sends these extracts from the February 1905 American Chess Bulletin (pages 29-30 and 31 respectively):

It will be recalled that Marshall played the French Defence (by transposition) in his most famous game, against Levitzky at Breslau, 1912. We add in passing that on page 27 of the February 1935 Chess Review Arnold Denker wrote regarding the conclusion of that game:

‘This is by far the finest and most artistic queen sacrifice that I have ever seen.’

(6984)

A further contribution from Olimpiu G. Urcan concerns the so-called ‘Fort Knox Variation’ (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Bd7). Who gave it that name, and when?

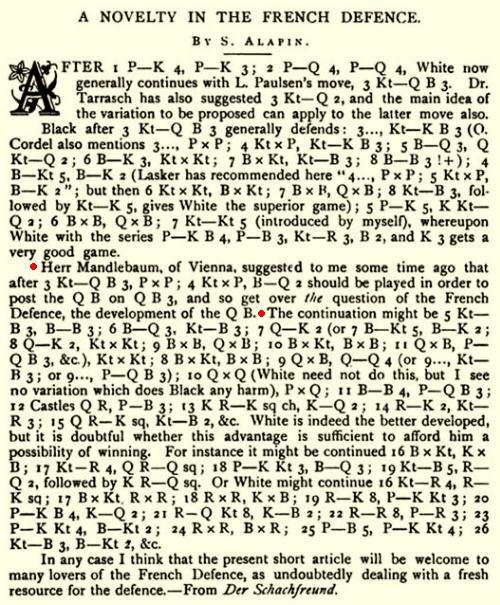

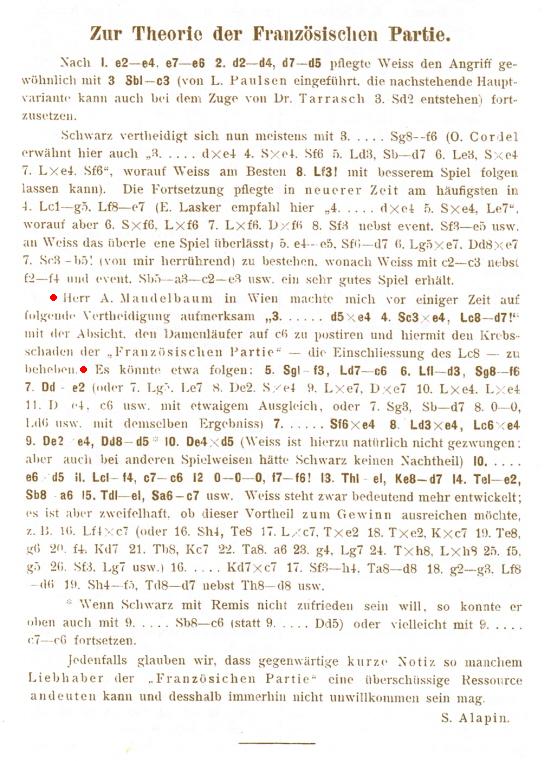

The above feature on page 471 of the November 1899 BCM has also been submitted by Mr Urcan, and we add Alapin’s original article (with the correct spelling Mandelbaum) on page 117 of Der Schachfreund, October 1899:

(7330)

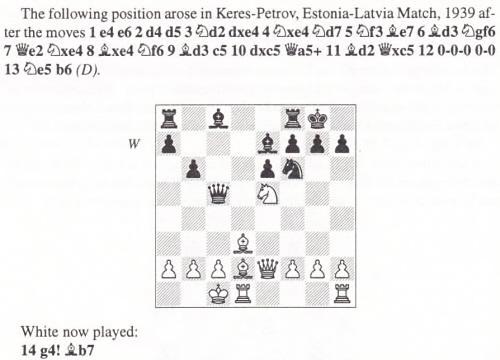

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) is surprised by the above, from page 210 of The Art of Attack in Chess by V. Vuković (London, 1998), because after 8...Nf6 ...

... the possibility of 9 Bxb7 is not mentioned.

Our initial comment is that in earlier editions of the book (in the descriptive notation – see page 237) the first 13 moves were not given.

Other authors have passed over in silence 9 Bd3 (which, incidentally, was not a novelty in 1939). See, for example, pages 262-263 of Modern Chess Opening Theory by A.S. Suetin (Oxford, 1965).

Keres himself referred to the line in his monograph on the French Defence (Örebro, 1957, page 176, and Moscow, 1958, page 149), giving 9 Bxb7 (‘!’) and making no mention of his game against Petrov.

Below are some annotators’ comments on the relevant phase of the Keres v Petrov game:

Al Horowitz, Chess Review, May 1939, page 106.

Schackvärlden, June 1939, page 209.

Keres’ Best Games of Chess 1931-1940 by F. Reinfeld (London, 1941), page 193.

Paul Keres Chess Master Class by Y. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1983), page 110.

Even so, there are writers who have suggested that 9 Bd3 may have been preferable to 9 Bxb7:

Turniere, Taten und Erfolge by E. Ridala (Berlin, 1959), page 70.

Paul Keres’ Best Games, volume two, by E. Varnusz (Oxford, 1990), page 139.

(8387)

On page 18 of the second edition of Ouvertures du jeu d’échecs (Neuchâtel and Paris, 1929) Marc Nicolet wrote a single sentence on the purpose of 1...e6 after 1 e4:

‘L’idée du coup e7-e6 est de couper l’attaque du F contre le pion f7.’

(9163)

From the recent book W.H.K. Pollock. A Chess Biography with 523 Games by Olimpiu G. Urcan and John S. Hilbert (C.N. 10459) we note the reference to the ‘Chigorin Variation’ 1 e4 e6 2 Qe2. Page 395 gives the game Pollock v Halpern, Staten Island, August 1893, with this note after White’s second move:

‘A seemingly new idea by Pollock which was later used extensively by Chigorin in important matches and tournaments. In annotating the second game of the Chigorin vs. Tarrasch 1893 match, in his 19 November 1893 Baltimore Sunday News column, Pollock wrote about 2 Qe2: “Introduced by the Editor. See News 19 August. The object is to stop …d5. Mason calls it ‘but a harmless violation of principle, yielding a strange game, a confusion of the Sicilian, Fianchetto and French.’” While annotating the same game for the 25 October 1893 New York Sun, Chigorin said nothing about 2 Qe2. However, the newspaper columnist remarked: “Chigorin introduced a novel move in the French game, namely 2 Qe2, and as a matter of course the game becomes doubly interesting, inasmuch as it might completely alter the theory of this defence. Chigorin in his notes, taken especially for the Sun, does not make any remarks regarding the move.” The 27 October 1893 edition of the Sun published the following from Pollock: “To the editor of the Sun: Sir: The move of 2 Qe2 in the French defence, which in your admirable report of today is described as novel and introduced by Chigorin, was played by myself against J. Halpern in the recent Staten Island cup tournament. Yours respectfully, W.H.K. Pollock.”’

Page 450 quotes from an article by Pollock in the Christmas 1893 issue of the BCM:

‘It was on Staten Island that I invented and discovered the move of 2 Qe2 in the French, since “spoiled” by the hibernations of the bear in the St Petersburg match. My old Richmond (Va) friend of the Daily News, and other London players, decry the move as inducing, instead of seducing the “Frenchman” to reply …d5.’

(10484)

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Nxf6+ Nxf6:

This opening occurred in Capablanca v Blanco, Havana, 1913, and White played 7 Ne5.

On page 26 of his tournament book, published the same year, Capablanca described the knight move as new and strong:

‘Nuevo, pero a mi juicio un golpe contundente para el negro que se ve imposibilitado de desarrollar su juego.’

In Chess Fundamentals (London, 1921) the Cuban wrote of 7 Ne5:

‘This move was first shown to me by the talented Venezuelan amateur, M. Ayala. The object is to prevent the development of Black’s queen’s bishop via QKt2, after P-QKt3, which is Black’s usual development in this variation. Generally it is bad to move the same piece twice in an opening before the other pieces are out, and the violation of that principle is the only objection that can be made to this move, which otherwise has everything to recommend it.’

Information is sought on Ayala. Page 193 of the 2015 McFarland edition of Miguel A. Sánchez’s work on Capablanca has an unsourced, unindexed reference to ‘a lesser known player such as the Venezuelan Martin Ayala’, who was named among those who ‘told the Cuban about new variations’.

Databases show that 7 Ne5 had been played before the Capablanca v Blanco game, and by Capablanca himself in a simultaneous game against R.H. Ramsey in Philadelphia on 6 January 1910:

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Nxf6+ Nxf6 7 Ne5 Bd6 8 f4 O-O 9 Be3 Nd5 10 Bd2 c5 11 c3 cxd4 12 cxd4 b6 13 Bd3 Bb7 14 O-O Nf6 15 Bc3 Rc8 16 Qe2 Qe7 17 f5 Bd5 18 fxe6 fxe6 19 Rae1 Bb4 20 Qe3 Bxa2 21 Qh3 g6 22 Bxg6 Bxc3 23 bxc3 hxg6 24 Nxg6 Qg7 25 Nxf8 Rxf8 26 Rf3 Qh7 27 Qg3+ Qg7 28 Qe5 Nd7 29 Qxg7+ Kxg7 30 Rxf8 Nxf8 31 Ra1 Bc4 32 Rxa7+ Kg6 33 Kf2 Nh7 34 Ke3 Nf6 35 Kf4 Nd5+ 36 Ke5 Nxc3 37 g4 b5 38 h4 b4 39 Rc7 Bd5 40 Kf4 b3 41 h5+ Kh6 42 g5+ Kxh5 43 g6 b2 44 g7 b1(Q) 45 White resigns.

The game was published in James Elverson’s chess column on page 7 of the magazine section of the Philadelphia Inquirer of 23 January 1910:

On Decoration Day, at the end of May 1909, 7 Ne5 was played in the board-one game between A.S. Meyer and A.K. Robinson in the match in Philadelphia between the Manhattan and Franklin chess clubs (American Chess Bulletin, July 1909, page 153).

Alekhine referred to Capablanca and Ne5 on page 203 of Gran Ajedrez (Madrid, 1947):

‘La jugada de Capablanca, 8 C5R, que ha estado de moda durante un cuarto de siglo, puede refutarse con 8...D4D! (el descubrimiento de Spielmann). Pero el blanco no necesita hacer tan exagerados esfuerzos para mantener la presión. Además de la jugada del texto, podría jugar 8 P3A, evitando por el momento la siguiente maniobra del negro.’

See also page 59 of 107 Great Chess Battles by A. Alekhine (Oxford, 1980). He was annotating the game Yanofsky v Dulanto from the 1939 International Team Tournament in Buenos Aires, but his reference to Capablanca and Spielmann was made in a position that occurred after 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 dxe4 5 Nxe4 Nbd7 6 Nf3 Be7 7 Nxf6+ Nxf6 ...

... and had not arisen in the Capablanca v Blanco game, which, as shown earlier, reached this position:

Yanofsky v Dulanto had the additional moves 4 Bg5 and 6...Be7.

Regarding the value of 8 Ne5 and 7 Ne5 in the respective positions, Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) writes:

‘With bishops on g5/e7: 8 Ne5 is only very rarely seen and does not score well. The reply 8...Qd5 is the third or fourth choice of the computer. It was seen in two out of 26 games in my Megabase and should be good enough to equalize.

With bishops on c1/f8: 7 Ne5 is not the most popular but scores rather well (as do other moves) and has been used by Nepomniachtchi in 2023 and 2024. The reply 7...Qd5 is seldom played and is not among the computer’s top choices. It indicates that 8 Be2 gives White an advantage.’

As regards Spielmann’s connection with ...Qd5 in the French Defence, below is the first part of Euwe’s annotations to Spielmann v Petrov, Margate, 1938, published on pages 311-313 of CHESS, 14 May 1938:

The scans from CHESS have been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

Addition on 26 October 2024:

Euwe stated in CHESS that at Margate (April 1938) Spielmann rejected 7 Ne5 on account of 7...Qd5, but Leonard Barden (London) points out to us that in June 1938 Spielmann did play 7 Ne5, against Sir George Thomas in the Noordwijk tournament. The game began 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Nxf6+ Nxf6 7 Ne5 Be7.

It was in the ninth round on 21 June 1938, as shown by, for instance, pages 34-35 of the Schaakwereld book on Noordwijk, 1938, published that year, and pages 76 and 79 of the (1971) volume in the Lachaga series.

(12052)

Addition on 9 December 2024:

Annotating a game in which he was Black against E.M. Jackson in the Third Anglo-American cable match, F.K. Young wrote after 1 e4 e6:

‘This inferior defence was adopted on account of the fast time limit.’

Source: American Chess Magazine, March 1898, page 582.

See also:

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.