12082. When

did Steinitz become world champion?

Bartlomiej Macieja (Lasek, Poland) refers to the

feature articles Early

Uses

of ‘World Chess Champion’ and World

Chess

Championship Rules and draws attention to a

further text, published a few days before the first

Steinitz v Lasker match began. Page 24

of the New York Times, 11 March 1894 stated:

‘For 26 years the veteran has successfully defended

the championship of the world.’

Also:

‘If a man who has held the world’s championship for

26 years accepts a challenge for a match which

promises to him less remuneration than matches he

contested before, he deserves some praise.’

The illustrated article was also published, with due

credit, on page 3 of the Montreal Daily Witness,

13 March 1894.

Nineteenth-century references to the duration of

Steinitz’s tenure are always welcome, regardless of

the view adopted.

12083.

‘Tournament champion’

Shortly before the start of the Carlsbad, 1907

tournament, Emanuel Lasker wrote on page 10 of the New

York Evening Post, 7 August 1907:

‘The only notable absentee is Dr Tarrasch, who has

been hailed as “tournament champion” since he won

the “champions’ tournament” at Ostend. What title

will be conferred on the winner of this tournament

[Carlsbad] is rather puzzling at present.

As the list of entries includes all those who

played in the “champions’ tournament”, with the

exception of Dr Tarrasch, and includes Maróczy and

many of the ingenious young players who are coming

to the front, the Carlsbad tournament must be

considered to be of the same class as that of

Ostend, and it seems illogical to award the title of

“champion” to the winner of one tournament and

withhold it from the winner of the other.’

12084.

Cohn v Chigorin

Many books have the game between E. Cohn and

Chigorin, Carlsbad, 1907, for which White shared the

second brilliancy prize. Much has been written about

11 f4, a move upon which Emanuel Lasker remarked:

‘Mr Cohn frankly admitted that he did not see that

he would lose a pawn by this move. That it turns out

a “sacrifice”, and not a loss, is more good luck

than good management.’

Lasker gave the game on page 9 of 12 October 1907

edition of the New York Evening Post, and his

comments about the ‘Irregular Opening’ are noteworthy:

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 d6 3 Nc3 Nbd7 4 e4

‘Players like Chigorin undoubtedly dread the usual

routine of the queen’s pawn opening, because of the

difficulty which, as Black, they must experience

before they can hope to attain any kind of attack or

superiority. By some curious process of reasoning

they resort to outlandish manoeuvres, hoping that

something beneficial might turn up, or that

irregularity may help originality. And so this

position arises, where White has freedom and Black

confinement. And this at no cost to White of

material or weakness on the right, left or centre of

the board. Conceding such an advantage, the result

is inevitable against correct play. The queen’s pawn

opening is certainly very strong for White, as

indeed are many other openings. But the philosophy

which induces a player with the black pieces to hope

to win with moves which it is impossible to conceive

are the best available only increases the inherent

difficulties that have to be contended against.’

12085.

Mexico

Is there a reader in Mexico who has access to

archival materials of the country and who would be

prepared to undertake some chess research on behalf of

a C.N. correspondent?

12086.

Anti-Turton

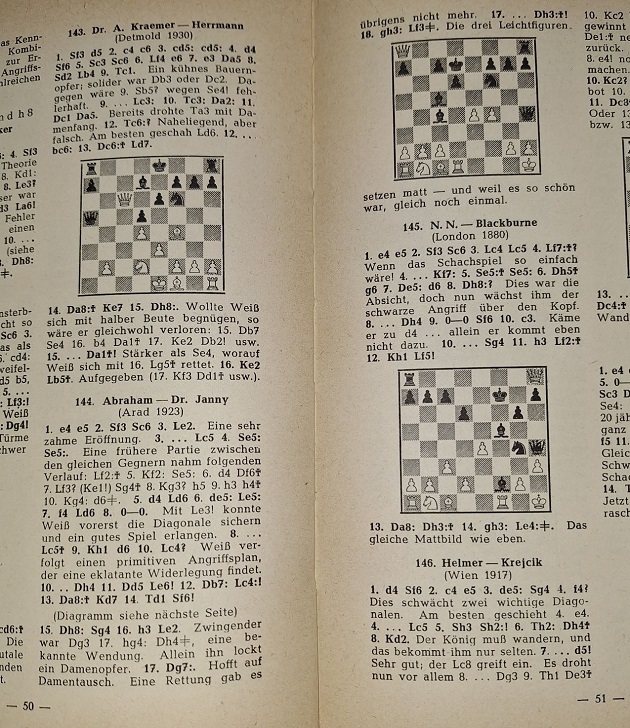

White to move

1 d4 would be met by 1...Qe2, and White therefore

deployed the anti-Turton

motif with 1 Rd2. A correspondent gave this position

(Lucarelli v Carra, Bologna, 1932 or 1933) in C.N.

681, but further particulars (and most notably the

full game-score) have not been traced. The two

surnames can be found in Italian chess literature of

about a century ago (often, in the second case, with

the spelling Carrà), but when was the position, if not

the full game, first seen in print?

Jens Askgaard (Køge, Denmark) writes:

‘The position from the game Lucarelli-Carra

appears on page 109 of Schackkavalkad by

Kurt Richter (Stockholm, 1949), translated from

the original Kurzgeschichten um Schachfiguren

(Berlin, 1947):

The date is given as 1933. Instead of Black

resigning after 1 Rd2 Rxd2 2 d4 Qe2 3 Bc1, the

book says that White won easily thanks to his

strong passed pawn on h6.

I would add that 2...Qe2 is a losing mistake for

Black. Instead, he could have played the

anti-anti-Turton move 2...Rf2, or 2...Bh2, which

my computer suggests as the best move.’

The position was on page 101 of the 1947 original

edition. Had Richter already used it elsewhere?

12087.

Ordinal numbers (C.N. 12033)

C.N. 12033 asked when and where the practice arose of

referring to world chess champions with ordinal

numbers.

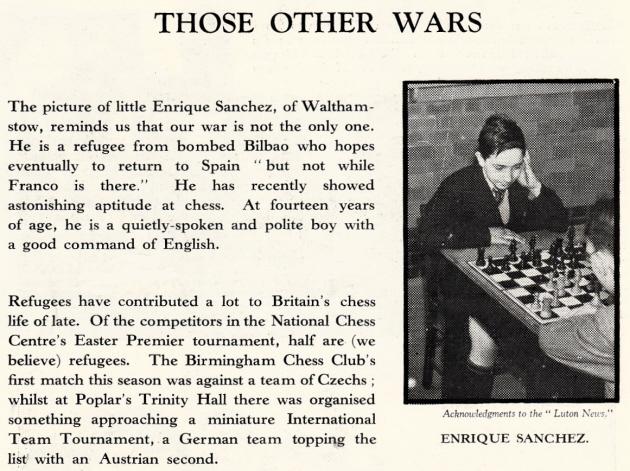

From Dmitriy Komendenko (St Petersburg, Russia):

‘In Soviet sources I have found no instances of

Botvinnik being called “the sixth world champion”

during his first term (1948-51), although quite

often he was called “the first Soviet champion”.

The description “sixth world champion” can be

found in articles published in 1951 in advance of

his match against Bronstein, one example being a

summary of the history of the chess matches on

page 5 of the 15 March 1951 edition of the

newspaper Советский спорт:

Frequent use of ordinal numbers seems to have

begun with Smyslov. For instance, in an article on

page 31 of the 16/1957 issue of Огонёк

Flohr wrote, “Smyslov wants to be the seventh

champion of the world in chess history”.

Other examples from 1957 can be quoted, such as

the 19/1957 edition of Огонёк, page 31,

where the writer, again Flohr, called for three

times hurrah to celebrate the new, seventh world

champion:

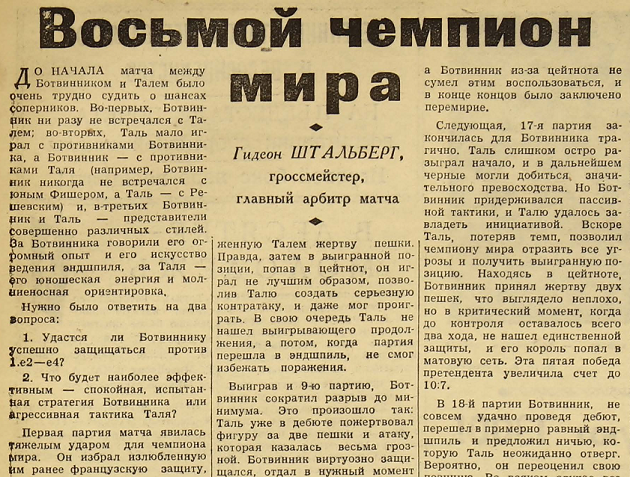

Starting with Tal, the practice became

increasingly common. On page 3 of Советский

спорт, 11 May 1960 an article by Gideon

Ståhlberg, who was the chief arbiter of that

year’s title match, was headed “The eighth world

champion”:

A production by the Central Studio for

Documentary Film (ЦСДФ) had the same

title with reference to Tal. The tradition

had been established and continued with Petrosian,

Spassky, Fischer, etc.’

12088.

Robert Hübner (1948-2025)

The late Robert Hübner’s great strength as a player

and analyst should not cause his legacy as a chess

historian and critic to be overlooked. The C.N. search

window can be used to locate a number of items which

refer to his forensic skills.

12089. The

writings of Robert Hübner

In his ChessBase ‘Two

Knights

Talk’ conversation with Arne Kähler on 17

January 2025, Johannes Fischer described Hübner as ‘an

absolutely brilliant writer’ and expressed

astonishment that so little of his output has appeared

in English.

12090.

Keres v Alexander

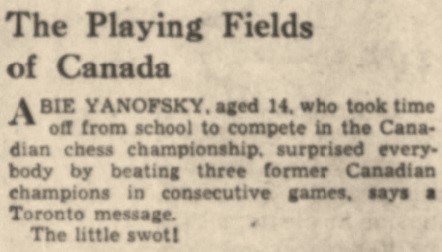

This photograph of Paul Keres and C.H.O’D. Alexander

is reproduced courtesy of the Hulton Archive. It was

taken during Hastings, 1954-55, but the board position

is unrelated to their game in the tournament.

12091.

Staunton and Saint-Amant

As cited in C.N. 8134, G.H. Diggle’s review of The

Kings of Chess by William

Hartston noted the inclusion of a cartoon

depicting ‘Staunton’s final victory over Saint-Amant,

with his supporters singing the National Anthem in the

background’.

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) draws

attention to the cartoon’s appearance on page 151 of Les

Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, issue 49,

September-October 1935:

Our correspondent adds:

‘La Revue Caricaturale published the work

of major French caricaturists, including the

celebrated Honoré Daumier. The chess cartoon, by

Charles Vernier, appeared in the 5 January 1844

edition. It is shown on the Bordeaux website Séléné,

although with a notice which appears incorrect

regarding the place of first publication (not

Bordeaux but Paris).’

12092.

Howard L. Dolde

Source: the conclusion of Chernev’s Chess Corner on

page 237 of Chess Review, August 1952.

Such presentation of quotes, lacking any context

(e.g. Capablanca’s age at the time, and whether the

words were written or spoken), was a trait of past

chess writers, even good ones. Today, the absence of a

source leaves any writer open to scepticism.

Capablanca’s remark was discussed on pages 85-86 of

our 1989 monograph, as well as in C.N.s 6172 and 9630.

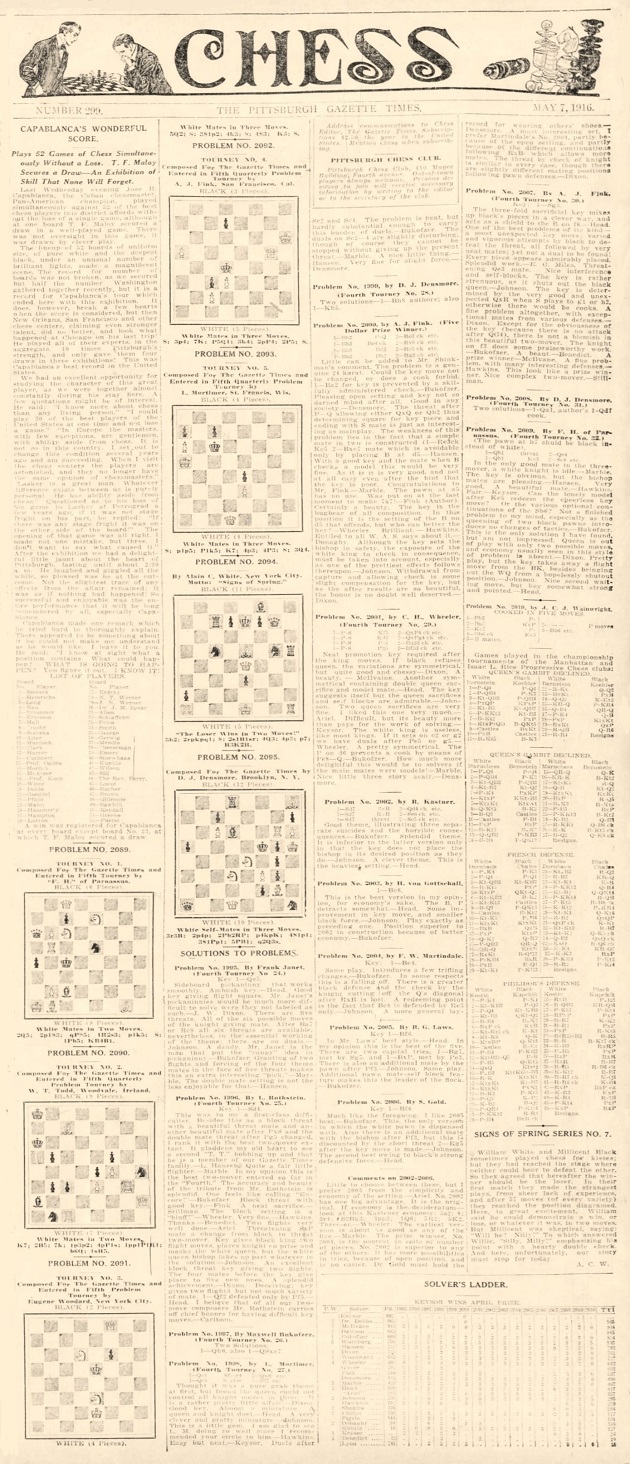

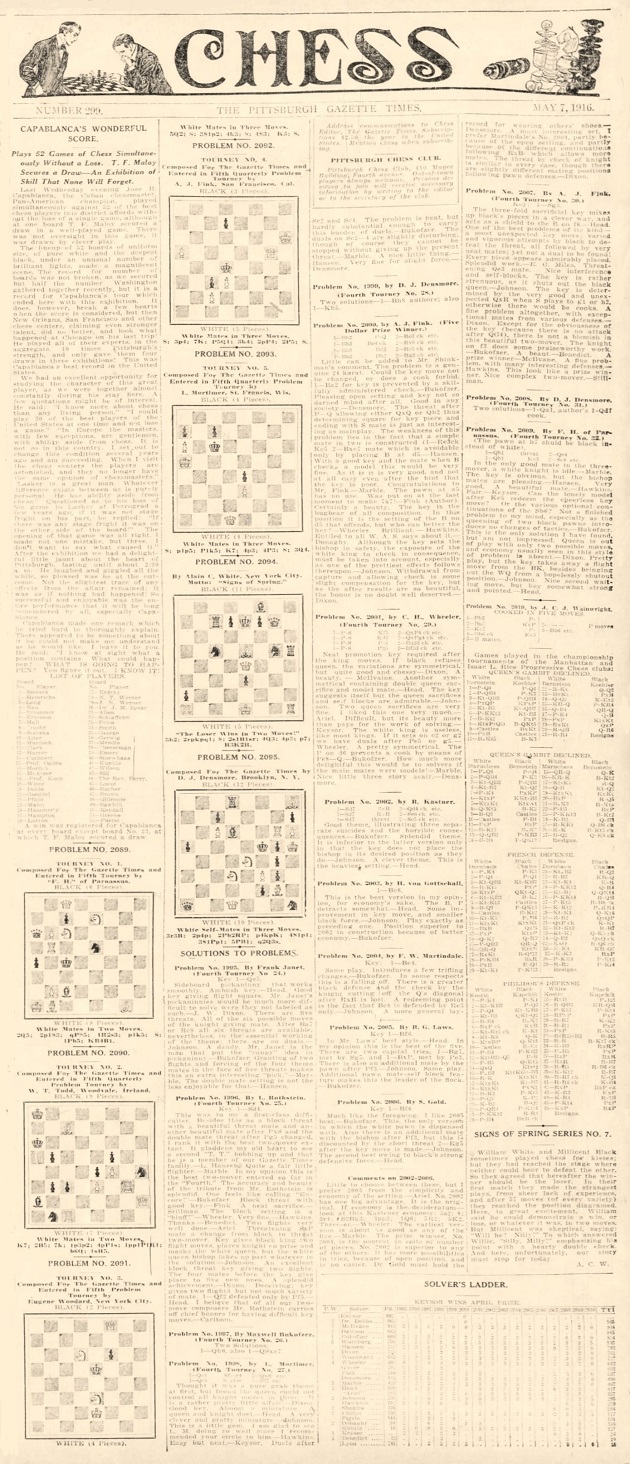

Below is the full (faint) column in which it first

appeared, on page 8 of the sixth section of the Pittsburgh

Gazette Times, 7 May 1916:

Larger

version

The columnist, who focussed very much on chess

problems, was Howard Louis Dolde (1884-1943).

From page 6 of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 7

September 1943:

We note too that the previous day, page 17 of the

newspaper had referred to a coroner’s report on the

cause of death:

For other information on Dolde, see an article by

Neil Brennen on pages 276-287 of the 8/2002 Quarterly

for Chess History.

Addition on 23 January 2025:

Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, below is an

extract from page 82 of the April 1910 American

Chess Bulletin:

12093.

The death of T.W. Barnes

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘Thomas Wilson Barnes had the best record of any

of the British players against Morphy in offhand

games. Born in Ireland about 1825 (source: 1871

census), he qualified as a barrister at the Middle

Temple, but was non-practising for a number of

years.

Like Deschapelles, as well as being an

exceptionally strong chessplayer he excelled at

whist. When Barnes led trumps, the game was over,

said an obituary.

The same obituary (“Whist Jottings”, Westminster

Papers, 1 September 1874, pages 99-100) described

in detail the symptoms of his last illness:

“His illness has been a long and painful one.

This time last year he weighed 16 stones; he went

abroad and his strength seemed suddenly to leave

him. With difficulty he got into a cab. He

gradually wasted away, until he became 7 st. 8

lb., and this was the last time he was weighed

(two months since), and he was certainly much less

weight at the last. Physicians were in vain. No

one really knows the cause of his death; some have

suspected a cancer in the stomach, and,

unfortunately, he would not give permission to

have a post mortem, so that the real cause will

remain a matter of surmise. Our impression is that

he died from ‘banting’. From being an enormous

eater he suddenly stopped his food, taking meat

only once a week; and soon, from want of use, his

stomach refused to fulfil its functions. He died

in peace, and desired kind remembrances to all his

friends. To us his last words were whispered,

‘Kind, kind to the last; God bless your wife and

little ones’. He lost his voice ten days before

his death, and for 12 days he ate nothing ...”

“Banting” was a low carbohydrate diet system,

named after its originator, William Banting.

A transcript of Barnes’ death certificate

follows:

“When and where died: 20 August 1874, 68

Cambridge Street

Name and surname: Thomas Wilson Barnes

Sex: Male

Age: 49 years

Rank or profession: Barrister at Law

Cause of death: ‘Malignant disease of the Stomach

some months Certified’

Signature, description and residence of informant:

Jane Simpson Present at the Death Madden Rectory

Armagh Ireland

When registered: Twenty second August 1874

Signature of registrar: WP Griffith (?) Registrar”

Source: General Register Office, Deaths, Sept.

quarter 1874, St George

Hanover Square, Vol. 1A, page 225)”

The cause of death, “Malignant disease of the

Stomach some months Certified”, seems, to a

medical layman such as myself, to account for the

symptoms of rapid weight loss which have been

alleged by some to be the result of “banting”.

The Calendar of Wills and Administrations

(Dublin) for the year 1874 contains the following

entry:

“Barnes Thomas Wilson

Effects under £5,000

15 October

The will of Thomas Wilson Barnes late of Middle

Temple and 68 Cambridge Street London

Barrister-at-Law deceased who died 13 August 1874

at 68 Cambridge Street was proved at the Principal

Registry by the oaths of Reverend Samuel Simpson

of Derrynoose Rectory County Armagh Clerk and

Alexander Duke Simpson of Belfast Captain 13th

Foot two of the Executors.”

Although there is the above entry in the

calendar, the actual will has not survived, owing

to a fire in Dublin in 1922.

For some reason, the date of death given above

is one week earlier than that contained in the

death certificate.

Barnes was buried in Brompton Cemetery on 25

August 1874. Source: the Royal

Parks website.’

12094.

S.S. Boden

John Townsend also provides ‘some random notes on the

life of S.S. Boden’:

‘Samuel Standidge Boden was born on 4 May 1826

at West Retford, Nottinghamshire. Although some

sources, including the Oxford Companion to

Chess, have specified East Retford, the place of

birth is clear in his baptism entry in the

register of the independent chapel at Chapel Gate,

East Retford (source: National Archives, RG 4

/3217, folio 7):

“Samuel Standidge, son of James and Mary Frances

Boden, was born 4th of May 1826 in the parish of

West Retford, and baptized July 27th in the same

year. Jas. Boden.”

The chapel was nonconformist, and the

officiating minister was his father, James Boden,

whose father, in turn, James Boden, was a

well-known Congregationalist minister at Sheffield

and elsewhere.

James Boden junior was baptized on 28 August

1791 at Hanley Tabernacle, Staffordshire, an

independent chapel (National Archives, RG 4/1871).

He preached at Retford for a few years before

moving with his work, and the 1841 census shows

him as an Independent Minister, together with his

family, including the 14-year-old Samuel, at

“Riding Fields”, Beverley (National Archives, HO

107 1229/43, page 44).

Later that year, James Boden senior died. His

will styled him “Reverend James Boden, Minister of

the Gospel, of Sheffield” (National Archives, PROB

11/1953/196). James Boden junior was named as a

legatee, but not the future chessplayer, Samuel,

who was a grandson.

The loss at Chesterfield of Charlotte Boden,

widow of the elder James, followed on quickly in

1843. James Boden junior, father of Samuel, had

lost both parents within two years. During 1843

and 1844, he was mentioned a few times in the

local press in connection with a chapel in

Beverley and with the Mechanics’ Institute. The

last reference I have to his duties as a minister

in Beverley is a document noted in the catalogue

of the archives at Hull History Centre, L

DCFS/6/2/2/59/3: “Resolutions concerning the

employment of Mr Boden at Lairgate Chapel during

the illness of Rev. John Mather”, dated 1843, an

item which I have not examined.

The Hull Advertiser, 24 November 1843,

page 4, carried a news item about the Mechanics’

Institute, Beverley, in which he is recorded as

having proposed a vote of thanks. Similarly, there

is a reference to him in the Hull Advertiser,

8 March 1844, page 3, when he was reported as

having delivered a lecture on magnetism to the

Beverley and East Riding Mechanics’ Institute, of

which he was one of the vice-presidents.

Thereafter, I have no more information about James

Boden until his death in 1851.

His wife, Mary Frances Boden, moved to Hull, her

native town, with or without her husband. Rev.

William Wayte, writing in the BCM

(February 1882, page 56), affirmed Samuel Boden’s

association with Hull:

“Before he came to London, Mr Boden was known as

the strongest player of the Hull Chess Club”;

Some chess writers erroneously gave Hull as

Boden’s birthplace.

An obituary of Samuel Boden in the Chess

Player’s Chronicle (18 January 1882, page 31)

notes that he started life as a railway clerk and

it later makes the following observation:

“On coming into some property, through the death

of a relative, he devoted himself to art. This

necessarily left him but little time for chess and

its practice.”

The Westminster Papers (1 September

1876, page 89) states:

“About 27 years ago there came to London from

Hull a young gentleman, then 25 years of age,

whose immediate destiny was a desk in the offices

of the South Eastern Railway at Nine Elms.”

There seems to be an inconsistency in this last

remark, since Nine Elms was in the South Western

Railway Company. A document noted in the catalogue

of the National Archives, RAIL 411/665, offers the

possibility of some information concerning Boden’s

railway career among records of the staff of Nine

Elms. The document has not yet been examined.

Later in the Westminster Papers article,

it is asserted that “the death of a distant

relative some years ago” enabled him to

“relinquish railway accounting”.

The known sources of his inheritances through

the deaths of relatives were twofold. Firstly, his

maternal grandfather, John Thornton, a gentleman,

died in Hull in 1845, leaving a will which was

written on 20 August 1844, a codicil being added

on 29 July 1845, with probate granted on 28 August

1845 (National Archives, PROB 11/2027/205). The

dwelling house at the time of the testator’s

decease was given to his daughter (Boden’s mother)

during her life:

“ ... upon trust to permit my said daughter Mary

Frances Boden to have the use and enjoyment

thereof during her life exclusively of her present

or any future husband and without being in any

manner subjct to his debts control interference

and in all respects as if she was a feme sole

and after her decease I direct the same to sink

into and be considered as part of my residuary

personal estate and to be applied and disposed of

accordingly ...”

She received a lifetime interest in other

properties. The will mentions property in Hull,

including in Albion Street and Storey Street. S.S.

Boden was not one of the biggest winners from this

will, but he stood to benefit in the long term

through his mother, whom, in the event, he

outlived by only three years. In addition, a trust

fund was set up for the benefit of his mother and

her children, and, more specifically, he was given

a lump sum of £400 at the age of 21:

“... upon trust to pay thereout to each of the

sons of my said daughter Mary Frances Boden

(including the said John Thornton Boden and Edward

Boden) who may have attained the age of 21 years

or as and when they shall respectively attain that

age the sum of four hundred pounds ...”

The date of Boden’s coming of age was 4 May

1847, but it is open to question whether he gave

up his alleged job as a railway employee shortly

after coming of age.

The second known inheritance came not from “a

distant relative”, but from his father. The

following facts are taken from his death

certificate (General Register Office, Deaths,

December quarter 1851, Shoreditch, Vol. 2, page

327). James Boden died on 8 December 1851 at 11

Albert Place, Shepherdess Walk, Hoxton New Town

(Middlesex); male, 62 years, gentleman; cause of

death: “Typhoid Fever Peritonitis Pleuritis

Pneumonia Gangrine, 24 Days Certified”; informant

George Booth, present at the death, of the same

address; registered 10 December 1851.

George Booth was already living at 11 Albert

Place on 31 March 1851, the day of the 1851

census, where he was described as a watch

finisher; aged 37 and born in the City of London,

he lived there with his wife, Louisa, and two

children (National Archives, HO 107/1535, page

number illegible). The nature of his relationship

with the deceased, James Boden, is unknown.

James Boden was buried at the church of St John

the Baptist, Hoxton, on 11 December, the

officiating minister, by whom the ceremony was

performed, being his own son, Edward Boden, of

Huddersfield. The 1851 census finds Edward Boden

in Huddersfield, described as born at Retford,

aged 28, “B.A. Camb. Vice-Principal” of the

Collegiate School there (National Archives, HO

107/2295, page 41). A minor discrepancy between

the age of 61 in the burial register and of 62 on

the death certificate is of no consequence.

The Huddersfield Chronicle (20 December

1851, page 8) reported that “on Thursday morning

last” at the distribution of prizes at the

Collegiate School “the Rev. Mr Boden was

unavoidably absent, having been called to Ripon by

the bishop to take priests’ orders”. It seems a

little odd that the report made no mention of his

having presided at his father’s burial, or,

indeed, of the death of a minister who was

formerly a widely-known figure in Yorkshire church

circles. When James Boden senior had died, there

had been an insertion in Gentleman’s Magazine,

as there had been for his widow, Charlotte Boden.

James Boden died without a valid will, and,

accordingly, letters of administration were

granted in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury to

Samuel S. Boden, of Thavie’s Inn (source: Indexes

to death duty registers, National Archives,

IR27/60, folio 14). The assets of an intestate are

divided between the closest relatives according to

set rules; in this instance, one would expect the

widow to receive the lion’s share, with smaller

portions going to the several children. For those

requiring full details of the assets thus

inherited by Boden the chessplayer, inspection of

the appropriate death duty register in IR 26 at

the National Archives at Kew should satisfy their

curiosity; the letters of administration will be

found in PROB 6.

Boden’s residence for a number of years,

Thavie’s Inn, situated at Holborn, was originally

used exclusively by lawyers, but by this time was

available as accommodation for anyone willing to

pay the going price. In fact, S.S. Boden is to be

found there at the time of the 1851 census

(National Archives, HO 107/1527, page 36). He

lived in a boarding house run by Anne Cocker, a

53-year-old single woman, born at Hathersage,

Derbyshire. Through an error in enumeration,

Boden’s name has been recorded as “Samuel S. Bax”,

but other details make it obvious that it should

read “Samuel S. Boden”: he is described as a

boarder, unmarried, aged 24, a gentleman, born at

Retford, Notts.; above all, corroboration is

provided by the “Thavie’s Inn” which appears in

the indexes to death duty registers (see above);

moreover, Boden was associated with Thavie’s Inn

during Morphy’s time in England, viz.:

“We have the pleasure this month of completing

the publication of the series of games contested

in 1858 between Mr Morphy and Mr Boden. The

following game, hitherto unpublished, was played

between these eminent masters, at Mr Boden’s

Chambers, in Thavie’s Inn, on the evening of 9

July 1858. The Rev. S.W. Earnshaw, to whom we are

indebted for it, was present on the occasion, and

recorded the moves.”

(Source: the Westminster Papers, 1 April

1876, page 241.)

Spare a thought for Boden’s father. What

happened to him? He became detached from his wife

and the rest of his family, and his death in 1851

was hushed up, suggesting that his family was not

proud of him. Since he died in Hoxton, my first

thought was that he may have spent some time in

the lunatic asylum at Hoxton, but I have so far

found no evidence of that. He may have had a

change of career, a marital break-up, moved to

another area, become an insolvent debtor, or

become ill in some other way. Various

possibilities remain open.

G.A. MacDonnell quotes Boden as recalling when

he first met Bird at the Divan in the Strand, in The

Knights and Kings of Chess, (London, 1894), page

44. That implies that Boden had himself started to

visit there by 1846.

In 1847 Hull hosted the anniversary of the

Yorkshire Chess Association (Chess Player’s

Chronicle, 1847, pages 159-164). In fact, two

Bodens attended: “Mr Boden, from Settle”,

presumably, John Thornton Boden, elder brother of

S.S. Boden, and “Boden”, by inference a Hull

member, who is taken to be S.S. Boden himself. He

won a game there from Harrwitz, who was playing

blindfold and simultaneously, which earned him

this favourable comment from Staunton:

“ ... Mr Boden, one of the most promising players

of the Northern clubs.”

Boden took a number of years to come to his best

as a player, his peak arriving in 1858. In 1851,

he won the London “Provincial” tournament. He beat

Rev. John Owen convincingly in a match in 1858,

but his match play successes were otherwise

limited. His reputation seems to have exceeded his

actual achievements. Morphy’s description of him

in 1858 as the strongest English player can be

valid only if one excludes Löwenthal on the

grounds that he was not naturalized until 1866,

and Staunton, because he had retired, since it

could be argued that both were stronger than Boden

in 1858.

By the time of the 1861 census, he had moved to

57 Pratt Street in the parish of St Pancras

(National Archives, RG 9/116, page 64). Here he

was a bachelor and lodger and described as an

“artist (landscape)”. Also living in St Pancras at

that time was the Irish master Francis Burden, who

for a time lodged with Cecil De Vere’s mother. The

two of them are both associated with having given

the young De Vere instruction in chess, but it is

not known that Boden ever lodged with Mrs De Vere,

and he probably coached De Vere at the Divan.

His later years were occupied primarily by art.

His whereabouts on the 1871 and 1881 censuses

remain to be discovered. He died on 13 January

1882, at 3 Tavistock Street, Bedford Square,

Middlesex, described as “artist (painter)”, his

age entered (incorrectly) as 56 (General Register

Office, Deaths, March quarter 1882, St Giles

district, volume 1B, page 453). His name was

entered incorrectly as “Samuel Standridge Boden”,

instead of Standidge. The cause of death was

“Enteric Fever 20 days Pneumonia 4 days Certified

by Charles Elam F.R.C.P.”, the informant being

Joseph Wurgler, present at the death, of 3

Tavistock Street. In the 1881 census, Joseph

Wurgler was a Swiss-born lodging house keeper,

living at that same address with his wife and

daughter (National Archives, RG 11 325, page 15),

so he is taken to have been Boden’s landlord.

According to the National Probate Calendar,

Boden’s personal estate amounted to £2,628 2s.,

probate of his will being granted on 14 April to

the executors, his brother Reverend Edward Boden

and the chessplayer Thomas Hewitt, a solicitor.’

12095.

A bishop ending

From pages 51-52 of the January-February 1907 Wiener

Schachzeitung:

The position was picked up by the BCM

(November 1907, page 489) ...

... and, with great enthusiasm, by Emanuel Lasker in

his New York Evening Post column, 18 December

1907, page 6:

12096. The

Monrad system

Carl Fredrik Johansson (Stockholm) enquires about the

origins of the Monrad pairing system, and we offer

some initial jottings.

An article by K.D. Monrad entitled ‘Et nyt

Turneringssystem’ (A New Tournament System) was

published on pages 40-41 of the April 1925 issue of

the Danish magazine Skakbladet, with a

follow-up article by him on page 81 of the July 1925

edition. There was extensive discussion of the system

in Norsk Schakblad, beginning on pages 130-132

of the September 1925 number (contributions by Erling

Wold and O. Trygve Dalseg) and continuing in December

1925, pages 180-181 (Erling Wold) and January-February

1926, page 13 (O. Trygve Dalseg).

All the above material can be conveniently viewed

online: see Skakbladet

and Norsk

Schakblad.

About K.D. Monrad, further information will follow,

with readers’ assistance. For the time being, we note

a reference on page 102 of the 6/1981 Skakbladet:

12097.

A worthy opponent

From Norsk Schakblad, March 1925, page 37:

Acknowledgement:

Cleveland Public Library

For other examples of this technique, see C.N.s 3221,

3224 and 6040 in Chess

Jottings.

12098.

Lasker on the Ruy López

Firstly, the text of C.N. 3058 (given on pages

325-326 of Chess Facts and Fables):

‘If you have Black, and your opponent plays 3

Bb5, your best move is to offer him a draw.’

This remark by Emanuel Lasker appeared in the Boston

Transcript of 31 January 1903, an item quoted

on page 130 of the March 1903 Checkmate. The

Boston newspaper commented:

‘And although this was a bit of pleasantry, Dr

Lasker did say in all seriousness that where the

second player in almost any other opening might

hope for a win, it was good judgment in the Ruy to

hope for a draw. The suggestion that the chess

world was waiting for some man who should begin an

exhaustive analysis of the Ruy early enough in

life to complete it, he dismissed with a

deprecatory shrug. “I’m afraid he would have to

continue it in the hereafter”, he said.’

We have wanted to verify the Checkmate

passage in the Boston newspaper and to add the page

number, but so far only a similar, not identical, text

has been found, on page 1 of the Boston Evening

Transcript, 2 February 1903:

12099.

Simultaneous displays by Lasker

By way of introduction to the now familiar

simultaneous game F.W. Dunn v Emanuel Lasker, London,

21 January 1908, which began 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4

Nf6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Nd4, Lasker’s column on page 7 of

the New York Evening Post, 28 March 1908

stated:

‘Simultaneous chess, which has now become so

popular, both here and in Europe, is capable of

furnishing entertainments and instruction to the

amateur chessplayer. But in order to make it so, it

is necessary that the single performer – usually a

master – should consider the interests of his

opponents, and instead of measuring his success by

the high score he can make, he should endeavor to

play all sorts of combinations, calculated to

exercise the ingenuity of his spectators. One should

not try to play perfect chess on such occasions,

for, to begin with, under the condition of play, one

cannot succeed in doing so and, on the other hand,

by introducing novelties that may lead to lively,

though perhaps unsound, attacks, one not only avoids

unduly prolonging the performance but also presents

to the spectators many interesting and exciting

positions. This sort of simultaneous chess also

appeals to the opposing players, who usually prefer

being defeated in a fair fight rather than being

gradually and dismally ground down by the proverbial

pawn plus.

Dr Lasker’s popularity as a simultaneous performer

is largely due to his following this method of

procedure. Always endeavoring to make his

exhibitions both entertaining and instructive, he

rarely follows the orthodox lines of play, but by

varying at some point endeavors to create

interesting situations that shall throw his

opponents [sic] on his own resources, and

enable him to exercise his ingenuity in finding the

best reply.’

A comprehensive

chronicle of his simultaneous displays from 1893

to 1940 is provided on the Emanuel

Lasker Online website.

12100. The

three shortest ever chess book reviews

Two

words.

One

word.

No

words.

12101.

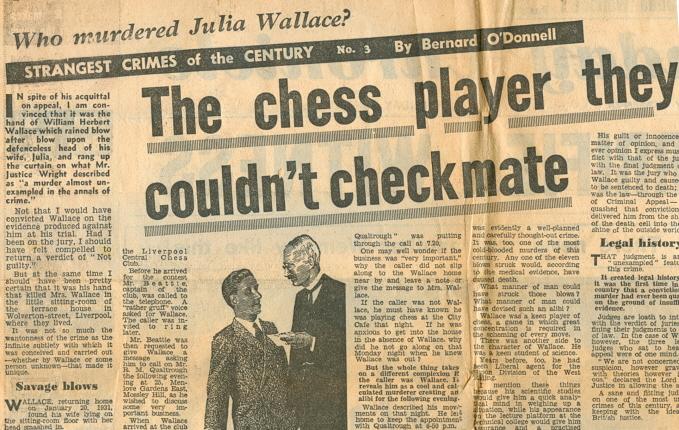

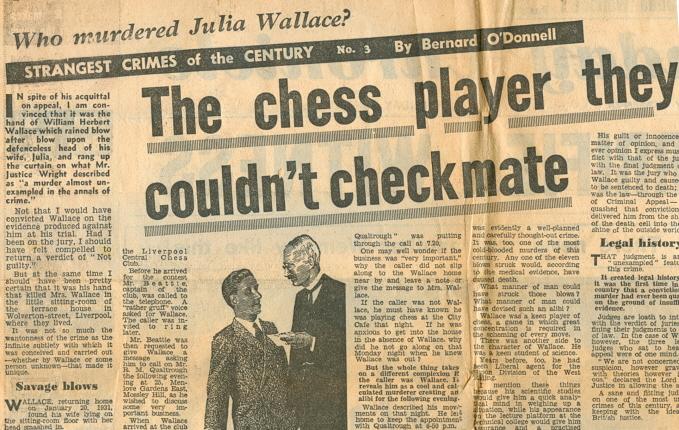

Wallace, Liverpool and Rubinstein

Any chess-related information about William Herbert

Wallace (1878-1933) and the Wallace

Murder

Case is of interest, and here we show a number

of local newspaper cuttings from the time when he was

a member of the Central Chess Club in Liverpool.

From the Liverpool Post & Mercury, 27

February 1930, page 14:

Five years previously, Akiba

Rubinstein had visited the city for a series of

chess engagements. As marked in red below, two of the

newspaper reports, on 27 February and 6 March,

included the name Wallace:

Evening Express

(Liverpool), 20 February 1925, page 6

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 25 February 1925, page 10

Liverpool Echo,

25 February 1925, page 7

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 26 February 1925, page 11

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 27 February 1925, page 13

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 28 February 1925, page 9

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 28 February 1925, page 11

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 6 March 1925, page 10.

12102.

Duchamp and Le Lionnais

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

‘I have come across an article written by

Raymond Keene entitled “Chips with a pinch of

salt: Duchamp and Le Lionnais” which appeared

online in The Article (thearticle.com), dated 7

December 2024. It contains material taken from

C.N. 9465 with no mention of you or Chess Notes.

However, Mr Keene did credit me with at least some

of it, describing me as “the late Oliver Beck of

Seattle”.’

12103.

Backgammon

From page 2 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10

March 1930:

12104.

Quote-pruning

C.N. 3212 quoted William Hartston’s exact words about

A History of Chess, on page 189 of The

Kings of Chess (London, 1985):

‘The classic book on the subject; 900 pages of

meticulous research, practically unreadable.’

12105.

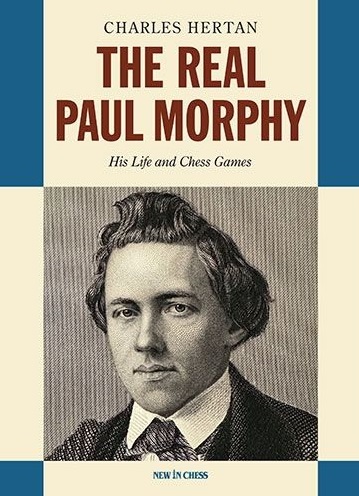

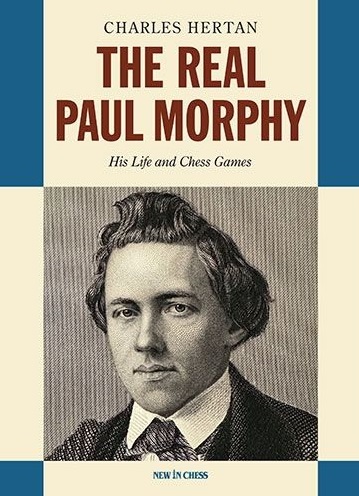

The Real Paul Morphy (C.N. 12018)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Pages 268-272 of psychotherapist Charles

Hertan’s recent book The Real Paul Morphy:

His Life and Chess Games (Alkmaar, 2024) contain

material about the Staunton-Morphy controversy.

For those needing a reminder, the controversy can

be seen as comprising the following phases in

1858:

1. Morphy arrives in England and challenges

Staunton to a match. The latter, who has retired

from match play, accepts, but points out that he

is under contract to produce an edition of

Shakespeare’s works, and he needs time to brush

up on his game.

2. Relations between the two belligerents

deteriorate through unfriendly exchanges in the

press and elsewhere.

3. At length, Staunton withdraws from the

negotiations. Relations continue to be bad and

never really improve.

I did not notice new information about the

controversy in this part of the book, or signs of

fresh research on the topic. Much of the content

in those pages is concerned with the quoting of

contemporary reports and documents which have

appeared in print before. For good measure, the

author treats us to some colourful remarks of his

own which reveal a one-sided stance in favour of

Morphy.

Treatment of the Staunton-Morphy controversy in

Chess Notes, going back to the 1980s, has included

contributions from, among others, Louis Blair,

G.H. Diggle, Frank Skoff and Kenneth Whyld, and

the quartet of feature articles below includes

many lively exchanges:

Edge,

Morphy

and Staunton

A

Debate on Staunton, Morphy and Edge

Supplement

to

‘A Debate on Staunton, Morphy and Edge’

Edge

Letters

to Fiske.

The C.N. discussions have been conducted in an

editorially impartial and even-handed manner, but

it seems that even-handedness was not part of Mr

Hertan’s objectives. He refers to Morphy sometimes

as “Paul”, while the supposed villain of the piece

has to make do with “Staunton”.

The following anti-Staunton language and

sentiment is to be found:

Page 268:

“Paul understandably doubted Staunton’s

intentions”

“... sucker punches received from Staunton in

the press ...”

“... Morphy shared his concern that Staunton

would try to evade the match, and pin the blame

on Paul ...”

Page 270:

“... but Staunton being Staunton, he couldn’t

resist taking more cheap shots at Morphy in his

column ...”

“... his shoddy treatment of the American ...”

Page 271:

“These actions were certainly petty and

ungracious on Staunton’s part”

“... the bitchy sniping of a humiliated

champion ...”

“... potshots at Morphy ...”

“... rattled by Staunton’s antics ...”

“... his unseemly behavior ...”

Page 272:

“... Staunton’s catty, distasteful behavior

...”

“But Staunton’s defenders never threw in the

towel.”

Page 273:

“Howard Staunton had a deeply flawed

personality.”

This last remark is perhaps the most damning of

these criticisms and is stated with the same

certainty as if Mr Hertan had had Staunton on the

psychiatrist’s (or psychotherapist’s) couch in his

consulting-room. It almost reaches the level of

conviction of Dale Brandreth, whom you quoted in Attacks

on Howard Staunton:

“… the fact is that the British have always had

their ‘thing’ about Morphy. They just can’t seem

to accept that Staunton was an unmitigated bastard

in his treatment of Morphy because he knew damned

well he could never have made any decent showing

against him in a match.”

Reference is made by Mr Hertan to the old

criticism that Staunton unfairly accused Morphy of

not having the stakes for the match. The latter

was hurt by the comments. Staunton had had

difficulties in the past with would-be match

opponents who could not readily muster the stakes,

an example being Daniel Harrwitz. He did not

invent the problem of Morphy’s stakes. In his book

Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess

(New York, 1976) David Lawson devotes a chapter to

the subject of Staunton and the stakes, which

reveals that Morphy’s family, the intended source

of the stakes, strongly disapproved of a match for

money. It is only too clear from Charles Maurian’s

letter of 27 July 1858 to D.W. Fiske that the

family’s attitude most certainly was a problem

which seriously threatened the match. Morphy had

kept from Maurian the extent of this disapproval

and the extraordinary lengths the family was

prepared to go to, which Maurian now revealed:

“... they were ready to send some responsible

agent to London whose duty it would be to let Mr

Morphy know that he must either decline playing or

continuing the match or that he will be brought

home by force if necessary; that they were

determined to prevent a money match by all means.”

(Lawson, pages 120-121)

Hinc illae lacrimae. Clearly, this ruled out

the family as the supplier of the stakes. It left

poor Maurian close to his wits’ end. Fortunately,

he acted promptly and, in a change of plan,

secured the £500 from another source, the New

Orleans Chess Club. He wrote again on 29 July 1858

with news that the amount had been raised. There

had been real uncertainty until Maurian’s decisive

action. Who can tell the exact time of arrival of

the funds? Neither are we likely ever to know how

much intelligence, if any, about Morphy’s family

difficulties reached Staunton’s ears. At the times

when he grumbled about Morphy’s lack of stakes, it

is likely that the money was yet to appear or, at

least, as far as he was aware. Staunton deserves

the benefit of the doubt here. His remarks are

likely to have been in response to a real

difficulty over stakes rather than a smear which

he had falsely concocted to discredit his young

adversary. Morphy’s family’s disapproval strongly

indicates that there was indeed a real problem

over the stakes.

Edge wanted the chess world to believe that it

was Staunton who asked for the stakes to be

reduced from £1,000 to £500, but it is much more

likely that any such request came from Morphy, in

the light of the family circumstances alluded to

above. Given a choice, Morphy would certainly have

preferred no stakes at all (“... reputation is

the only incentive I recognize”).

Another issue was Staunton’s contract with

Routledge to produce an edition of Shakespeare,

sometimes cited by his critics as an excuse for

not playing a match. One might have hoped that the

late Chris Ravilious had put this matter to bed

for good by his article in CHESS (December

1998, pages 32-33), in which he showed not only

that such a contract existed but also that it

contained specific penalty clauses for failure to

deliver parts of the work on time. Later, the

contract appeared in print in Tim Harding’s book,

Eminent Victorian Chess Players (Jefferson,

2012), on pages 338-339.

Our understanding of the character of the

degenerate F.M. Edge, Morphy’s associate, has

taken giant steps forwards in recent years, so it

is disappointing that such material has not been

drawn upon by Mr Hertan. Edge certainly

contributed to the breakdown of negotiations for a

match. Good relations between Morphy and Staunton

were needed if the former wanted a match, but Edge

pulled in the opposite direction.

As events turned out, if there was ever going to

be a meeting of these two famous masters, it

needed to be at the Birmingham tournament.

Unfortunately, while Staunton played in this

event, and did badly, Morphy went to some lengths

to avoid such an encounter, even giving a phoney

excuse for his non-attendance. (See my

contribution in A

Debate on Staunton, Morphy and Edge.)

Staunton’s participation at Birmingham answers the

frequent criticism, also raised by Mr Hertan, that

he was afraid to meet Morphy: whether or not he

was matched against Morphy in Birmingham, he must

have known that it was likely he would lose there,

and he was not afraid of that; in the event, he

was beaten by Löwenthal.

The chief problem with Mr Hertan’s coverage of

the Staunton-Morphy affair is that virtually all

of it could have been written 50 years ago.

It may be a small slip on page 273 to give Frank

Skoff the wrong USCF title (he had been President,

not Director), but how could Mr Hertan offer, on

the same page, such an obviously incorrect

conclusion about the exchanges between Skoff and

Whyld? As I have observed elsewhere,

Whyld emerged from the debate severely battered.

Mr Hertan ends that paragraph by writing one

thing which is true: that there are “hundreds of

pages” of C.N. material on Staunton, Morphy and

Edge. The problem is that he shows no signs of

having read them.’

12106.

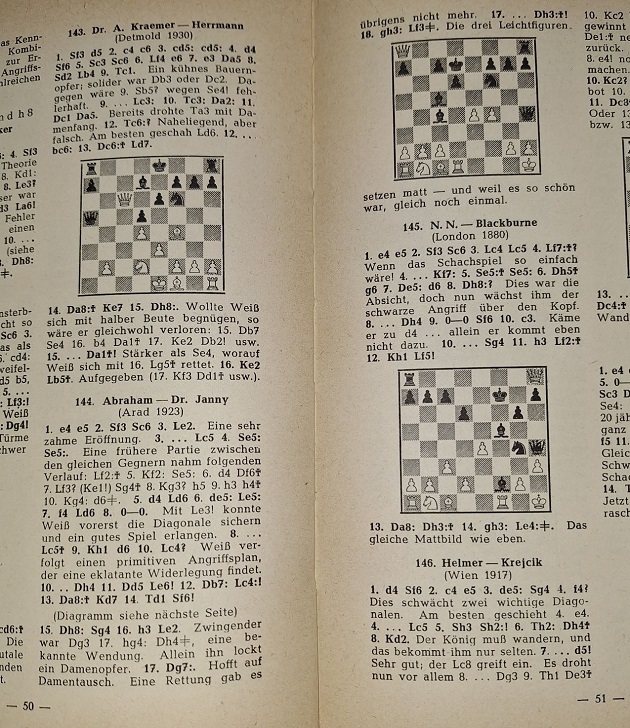

Abraham v Janine

From page 301 of 1000 Checkmate Combinations

by Victor Henkin (London, 2011):

Acknowledgement for

the scan: Cleveland Public Library

Karel

Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) points out the

following from pages 420-421 of the earlier Russian

edition, 1000 matovykh kombinatsiy (Moscow,

2003):

For Black, named as Джанни, one would expect to see

Dzhanni or Gianni, but what is known about either

player of the 1923 game, and about the occasion?

The position was also on page 358 of Tal's

Winning Chess Combinations by Mikhail Tal and

Victor Khenkin/Henkin (New York, 1979), labelled

Abraham v Gianni (1923).

12107.

Praeceptor Germaniae

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks:

‘Is it known when and by whom Siegbert Tarrasch

was given the title “Praeceptor Germaniae”?’

The following appears in Tarrasch’s Foreword to the

second edition of his Dreihundert Schachpartien

(Leipzig, 1909), page vii:

‘In den Münchener Neuesten Nachrichten

hat Herr v. Parish zu meinem Erstaunen erklärt,

daß ich längst den Ehrennamen “Praeceptor

Germaniae” trage.’

We note the following on page

13 of the 10 December 1905 edition of the Munich

newspaper:

‘Der Deutsche Schachbund hat das

Tarraschbüchlein allen seinen Mitgliedern zum

Geschenk gemacht und dadurch dokumentiert, daß es

zu dem eisernen Bestande jedes Schachfreundes

gehören sollte. Auch wir können nur wünschen, daß

durch eine möglichst weite Verbreitung und durch

ein ernstes Studium dieses Werkes die Vertiefung

des Schachs in ähnlicher Weise gefördert werde,

wie es durch des gleichen Autors „300 Partien“

geschehen, die ihm in der ganzen deutschen

Schachwelt den Ehrentitel eintrugen: praeceptor

Germaniae! v. P.’

12108.

Kostić v Caruso

As shown in our feature article on Boris

Kostić, C.N. 6951 reproduced a supposed loss to

Enrico Caruso, given by A. Soltis on pages 93-94 of Chess

to Enjoy (New York, 1978), with no place or date

or source stipulated. B. Pandolfini put ‘1918’ on page

106 of Treasure Chess (New York, 2007),

whereas some databases and page 55 of CHESS,

September 2004 had ‘New York, 1923’, even though

Caruso died in 1921.

Now we add that on page 18 of the November-December

1996 issue of Chess Horizons (acknowledgement:

Cleveland Public Library) Josef Vatnikov gave the

game, stating, without evidence, that it was ‘played

in New York in 1914’.

After just five words Vatnikov deployed ‘once’:

‘The great singer Enrico Caruso once said: “My

favorite opening, playing Black, was the Philidor’s

Defense.” In due time the famous Italian tenor

played a lot of games with the Yugoslav grandmaster

Bora Kostic, who was his chess trainer. “Caruso

liked chess very much”, said Kostich, “I appreciated

his chess ability. He could be on the offensive

perfectly. Probably, many chess masters would envy

his brilliant combinations.”’

There is no indication as to where any of this came

from.

12109.

Chess and music

From page 7 of the Sunday Sun (Newcastle), 12

February 1922:

The picture is a crude version of a photograph

on

Gallica mentioned in C.N. 9277.

Many newspapers reported in 1922 that Reshevsky and

Joseph Schwarz intended to give each other lessons.

The level of reportage is exemplified by page 3 of the

Buffalo Evening Times, 6 January 1922:

12110.

Hunting

Further to the role-playing exercises in C.N.s 11994,

12035 and 12060, readers are now invited to imagine

themselves investigating supposed measures to ban

chess in the Middle Ages, including, for example,

oft-told stories about Bishop Guy of Paris having a

chess board which was disguised by being folded.

Finding nothing in H.J.R. Murray’s books and

articles, the investigator may try a search engine,

the dubious reward being a plethora of similarly

worded paragraphs such as this:

‘In 1125, Bishop Guy of Paris banned chess and

excommunicated a few priests who were caught playing

chess. A chess enthusiast priest then devised a

secretive folding chess board. Once folded, it

looked like two books lying together.’

That is merely a sourceless item on a sourceless Bill

Wall webpage. Instead, Google

Books may seem promising since it offers

relevant (though not perfectly matching) texts, such

as the following:

That passage is on page 348 of the 6 May 1865 issue

of All the Year Round, ‘a weekly journal

conducted by Charles Dickens’. With C.N. 12043

(‘figurehead romanticism’) in mind, no excited

suggestion can be made that the article, entitled

‘Chess Chat’ and published on pages 345-349, was by

Dickens himself. All the Year Round articles

were usually anonymous. But who did write it, and on

what historical basis?

With such questions unresolved, one’s eye may well be

drawn to the last two paragraphs of the article, which

abruptly move on from chess history to some general

criticism of the game:

‘To play well at chess – “Cavendish” opines – is

too hard work. It is making a toil of a pleasure. We

resort to games as a relief, when we have already

experienced enough – perhaps more than enough –

brain excitement. Under those circumstances, we do

not desire severe mental exertion, but rather repose

of mind, which is not promoted by engaging in a

contest of pure skill. To take up chess, as an

amusement, after mental labour, is to jump out of

the frying-pan into the fire. Chess, well played, is

no relaxation, and ought not to be regarded as a

game at all. It is not a game with first-rate

performers, but the business of their lives. Chess

is their real work; ordinary engagements are their

relief. Sarah Battle “unbent” over a book.

But for what is all this intellectual

tension, this toil and trouble, this stretch of

thought? Simply to fill an otherwise unoccupied

portion of human life. “Labour for labour’s sake”,

says Locke, “is against nature. The understanding,

which, as well as the other faculties, chooses

always the shortest way to its end, would presently

obtain the knowledge it is about, and then set upon

some new inquiry.” But chess affords no information,

leads to no purpose, effects no result, leaves no

trace. It is a beautiful piece of mechanism,

conducing to nothing. When the number of known

combinations, problems, and solutions, shall have

been increased a hundred-fold, the world will not be

a jot the happier, the wiser, the better, or the

richer. Those who like thus to occupy their leisure,

have a perfect right so to do. If their striving and

straining do no good, at least it does no harm. But

it is difficult not to say to one’s self that the

total amount of effort bestowed on chess, say only

within the last hundred years, might have sufficed

to gird the world with trans-oceanic telegraphs, or

to work out the means of aërial locomotion.’

And so now there are two puzzles on the go: the

origin of the religious claims and the authorship of

the criticism of chess. For both matters, further

burrows beckon, and C.N. readers’ company and

assistance will, as ever, be appreciated.

12111.

The Chess Wheel

C.N. 472 (see Chess

Jottings) included the following comments by

Dale Brandreth in a catalogue:

‘The Chess Wheel, V. Armen, English Opening.

Similar to the circular slide rule. 65 variations.

More a novelty than anything else. Rather humorous

in that the author has boldly printed on the device

that “patent pending for all chess openings and

defenses on the wheel system”. What sublime

effrontery and ignorance. Did he invent all these

lines? No, of course not. Yet he has the gall to try

to patent them. The chess world does not lack its

buffoons either.’

Paul Calhoun (West Hartford, CT, USA) writes that the

criticism is unfair, and he has sent us a PDF

file which presents The Chess Wheel and

includes commendations.

12112.

Notation

Chess

Notation mentions cases where the algebraic is

less effective than the descriptive, e.g. the use of

‘Q-KKt6’ to record a queen sacrifice motif which in

algebraic is either ‘Qg6’ or ‘Qg3’.

Another case is the remark attributed to Bent Larsen

to the effect that with a knight on KB1 a player who

has castled on the king’s side is safe from a mating

attack. What exactly did Larsen say or write?

12113.

Streets

Concerning Street

Names

with Chess Connections, the report below comes

from page 6C of El Nuevo Herald, 12 August

2006:

The third paragraph of the article:

‘José Raúl Capablanca fue honrado por el Condado

de Miami Dade, que anunció ayer en conferencia de

prensa celebrada en el Cooper Park, que la calle

16 entre las avenidas 57 y 62 del S.W. llevará el

nombre del ilustre jugador.’

12114.

Definitive

In descriptions of chess books, has the word

‘definitive’ ever been used legitimately by a

publisher, author or reviewer – and to which volumes

could it be applied with justification?

See Hype

in

Chess.

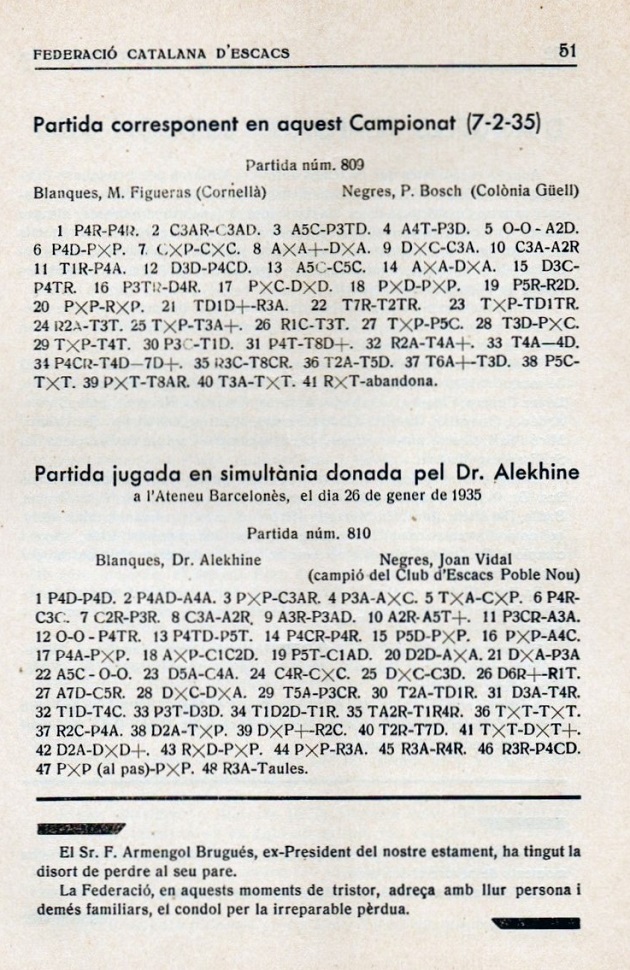

12115.

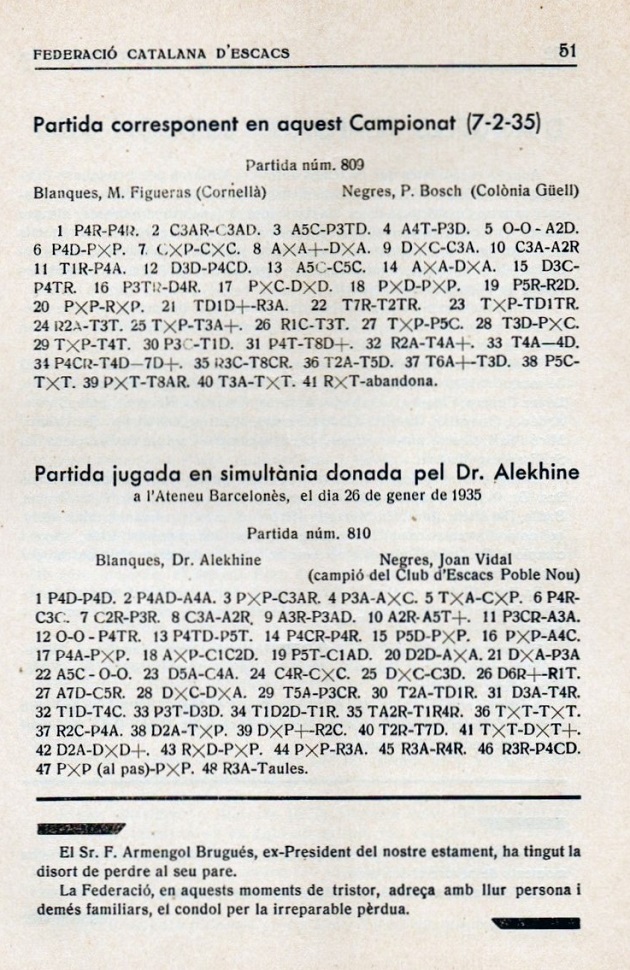

Alekhine v Vidal

Juan Carlos Sanz Menéndez (Alcorcón, Spain) draws

attention to page 51 of the Bultlletí de la

Federació Catalana D’Escacs, March-April 1935:

The Alekhine game against Joan Vidal played in

Barcelona on 26 January 1935:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 Bf5 3 cxd5 Nf6 4 f3 Bxb1 5 Rxb1 Nxd5 6

e4 Nb6 7 Ne2 e6 8 Nc3 Be7 9 Be3 c6 10 Be2 Bh4+ 11 g3

Bf6 12 O-O h5 13 a4 h4 14 g4 e5 15 d5 cxd5 16 exd5 Bg5

17 f4 exf4 18 Bxf4 N8d7 19 a5 Nc8 20 Qd2 Bxf4 21 Qxf4

f6 22 Bb5 O-O 23 Qf5 Nc5 24 Ne4 Nxe4 25 Qxe4 Nd6 26

Qe6+ Kh8 27 Bd7 Ne4 28 Qxe4 Qxd7 29 Rf5 g6 30 Rf2 Rae8

31 Qf3 Re5 32 Rd1 Rg5 33 h3 Qd6 34 Rdd2 Re8 35 Rfe2

Ree5 36 Rxe5 Rxe5 37 Kg2 f5 38 Qf2 Rxd5 39 Qxh4+ Kg7

40 Re2 Rd2 41 Rxd2 Qxd2+ 42 Qf2 Qxf2+ 43 Kxf2 fxg4 44

hxg4 Kf6 45 Kf3 Ke5 46 Ke3 b5 47 axb6 axb6 48 Kf3

Drawn.

Our correspondent adds the report on the event on

page 1782 of Els Escacs a Catalunya, February

1935:

‘Aquesta vegada ha efectuat dues session: la

primera tingué lloc el dia 26 a dos quarts d’onze

de la nit en l’Ateneu Barcelonès, on es congregà

una veritable multitud freturosa de seguir les

incidències de la sessió. Varen ésser-li oposat a

43 jugadors de diverses categories i a dos quarts

de sis de la matinada, després de set hores

consecutives de joc, acabà la sessió amb el

resultat de 33 partides guanyades, quatre

empatades i sis de perdudes (+ 33 =4 –6). Els

vencedors foren: Claret (Manresa), Dr. Julià (R.

López), Vivet (Caixa de Pensions), Sererols

(Comtal), Morera i Mansoso (Terrassa). Els qui

empataren foren : Vidal (P. Nou), Mestres

(Terrassa), Abrahams (Barcelona) i Serra Vinyes

(Badalona).’

12116.

Staunton world champion

From page 3 of the Newcastle Daily Chronicle,

27 July 1874:

Chess is not mentioned until the latter part of the

report, but the statement that Staunton ‘has

consequently been recognised as the champion chess

player of the world’ is noteworthy and is being added

to Early

Uses

of ‘World Chess Champion’.

12117.

Staunton and friendship

From page 7 of the Newcastle Courant, 15

December 1876 (chess columnist: William Mitcheson):

The marked text reads:

‘The late Mr Howard Staunton had the gift of making

serviceable friends in a very brief acquaintance,

and he had also the unenviable gift of throwing them

off when they had served his purpose.’

Does that claim hold up under scrutiny?

12118.

‘Abraham v Janine’ (C.N. 12106)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) submits the

full game, from pages 50-51 of Hohe Schule der

Schachtaktik by Kurt Richter (Berlin, 1956):

Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, below are

both pages from original 1952 edition of Richter’s

book:

Wanted: earlier appearances of the game, and details

of the occasion.

12119.

Alekhine in Who’s Who (C.N.s 741 & 9316)

Christian Sánchez writes:

‘Successive editions of Who’s Who

present the evolving, succinct autobiography of

their subjects. Through Alekhine’s entries, we can

trace the timeline of significant events in his

life: when he became a grandmaster, considered

himself a challenger, claimed to have earned his

doctorate in law, married, moved home and, even,

took up bridge.

Below, firstly, is his entry on page

29 of Who’s Who 1926 (London, 1926):

“ALEKHINE, (Aljechin) Alexander, chess master,

writer, and at present, student of Paris

University, for Law Doctorate; b. Moscow, 1 Nov.

1892; s. of A. Alekhine, Maréchal de Noblesse of

Voronej’s Government Nobility, and Member of the

Douma, and A. Prokoroff, d. of the Moscow

Industrial Magnate. Educ.: the Imperial High Law

School for Noblemen, the Pravovedenie, Petrograd.

After taking his law degree in 1914, entered the

Foreign Office; his career was interrupted by the

Revolution, when he emigrated to France; served

voluntarily in the Great War as Red Cross

representative at the front (Sign of the Red

Cross, the Military Cross of St Stanislas, and the

St George’s Cross); as chess player he got the

title of Master at the age of sixteen, 1909, and

the title of Great Master in 1914; has to his

credit more than twenty international Tournaments,

and holds the world’s record for Blindfold Chess

(New York 1924, and Paris 1925); challenger of

Capablanca for the World’s Championship in chess.

Publications: Chess in Soviet Russia, 1921; New

York Tournament Book, 1924; Hastings Tournament

Book, 1922; publications in French and foreign

periodicals; My Best Hundred Games. Recreations:

riding, canoeing, tennis. Address: 211 rue de la

Croix-Nivert, Paris XV.”

Changes or additions in subsequent editions:

1927: –;

1928: “Doctor of Law of Paris University; m.

Nadejda Fabritsky, widow of General V. Vassilieff;

[My Best Hundred Games], 1908-1923; N.Y.

Tournament Book, 1927.”

1929: “Chess Champion of the World since 1927; My

Best Games of Chess, 1927.”

1930: –;

1931: “Defended his title successfully 1929;

Produced a World’s record score in San Remo

Tournament, 1930; bridge.”

1932: –; 1933: –

1934:“on visiting Iceland, made Knight of the

Order of Falcon; On the Way to the World

Championship, 1932; ping pong.”

1935: “m. Grace Wishaar, widow of Captain

Archibald Freeman; [Blindfold Chess] Chicago

1933; [Defended his title successfully 1929] and

1934; Le Château, St. Aubin-le-Cauf, Seine

Inférieure, France.”

1936: –

1937: “[Chess Champion of the World], 1927-35;

on visiting French Africa was made Commandeur of

the Nichum Iftikar (sic: Nichan Iftikhar)

and Knight of the Ouissan Alaouit (sic:

Ouissam Alaouite); Zürich Tournament Book,

1934.”

1938: “Nottingham Tournament Book, 1936; Deux

Cents Parties d’Échecs, 1937.”

1939: “Chess Champion of the World; won the

world’s Title from J.R. Capablanca in 1927;

defended it successfully in 1928 [sic]

and 1934; lost it against Dr Euwe in 1935 and

regained it from him in 1937; London Tournament

Book, 1932.”

1940: –; 1941: –; 1942: –; 1943: –; 1944: –;

1945:–

1946: Obituary: 24 March 1946. Shown in

C.N. 9316.’

12120.

Marshall by John Hix

The ‘Strange as it seems’ feature by John Hix on page

15 of the Omaha World-Herald, 21 April 1931:

12121.

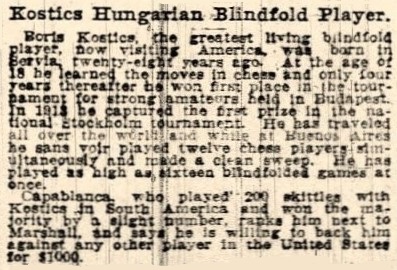

Skittles games between Capablanca and Kostić

From Ben R. Foster’s chess column on page b7 of the St

Louis Globe-Democrat, 18 July 1915:

Statements by and about Kostić require particular

care. What is known about the ‘200 skittles’ claim?

12122.

Capablanca and Kostić in Buenos Aires

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides this photograph

from an unnumbered page of Fray Mocho, 28

August 1914:

Larger

version

A red dot marks Kostić.

Can a better copy of the photograph be found?

12123.

Newspapers online

Viewing old newspapers online inevitably brings

occasional disappointments as a result of

illegibility:

Liverpool Post

& Mercury, 7 April 1923, page 4.

12124.

Newspapers online

Viewing old newspapers online inevitably brings

occasional disappointments as a result of legibility:

Illustrated Police

News, 9 January 1897, page 7

Evening Express,

18 July 1922, page 4

Liverpool Echo,

22 September 1942, page 4

12125. A

knight on K6

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘Your feature article A

Knight on K5, K6 or Q6 gives the earliest

date for the quote as 1929. In the notes to the

move 15...QR-Q1 in the Lasker-Capablanca game (St

Petersburg, 1914, round 18), page 66 of The

Grand International Masters’ Chess Tournament at St

Petersburg, 1914 (Philadelphia, [1914]) quotes

Louis van Vliet in the Sunday Times:

“Why allow Kt-K6, while it could be prevented by

B-B1? The great Anderssen used to say: ‘Once get a

Kt firmly posted at K6 and you may go to sleep.

Your game will then play itself!’ (V.)”.’

See note (e) below in the full column published on

page 17 of the 31 May 1914 edition of the Sunday

Times:

12126.

Abraham v Janny (C.N.s 12106 & 12118)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) provides page

315 of Schachjahrbuch 1923 by Ludwig Bachmann

(Ansbach, 1924):

No occasion is mentioned for the Abraham v Janny

game, but there are now the players’ initials.

12127.

Another Staunton obituary

Further to C.N. 12116, below is the obituary of

Howard Staunton on page 4 of The Scotsman, 29

June 1874:

Beyond such curiosities as ‘a native, we believe, of

Warwickshire’, ‘educated at Eton and Oxford’ and ‘the

conqueror of Murphy’, the text illustrates how

mainstream obituaries of Staunton might focus on

Shakespeare and not chess. The English-language Wikipedia

article on Staunton does the reverse.

Possible reasons for the decline in Staunton’s

standing as a Shakespeare authority were given by, in

particular, Richard Allen in C.N. 5603. See Howard

Staunton and William

Shakespeare

and Chess.

Attacks

on

Howard Staunton includes chess observations by,

among others, Fred Reinfeld, Al Horowitz and Larry

Evans. Remarks by Evans are discussed in detail in The Facts

about Larry Evans, and here is another one:

Reno

Gazette-Journal, 18 April 1987, page 33

12128.

The Menchik sisters

No information is available on whether any chess

outlet has ever paid money to getty

pictures for a large, clean copy of the above

photograph. Nor do we know why it is believed to show

Vera Menchik, as opposed to her sister Olga.

Complementing the images of the sisters in The

Vera Menchik Club, below is a photograph from

page 14 of the (London) Daily Chronicle, 13

January 1926:

12129.

Levitzky v Marshall, Breslau, 1912

Wanted: more detailed local (i.e. Breslau/Wrocław)

information about Marshall’s

‘Gold

Coins’

Game, and also about the loser.

Other games where a queen moves to KKt6 (i.e. g6 or

g3) are discussed in The

Fox

Enigma.

Frank James Marshall

by Frederick Orrett (see C.N. 9722)

Regarding the alleged gold coins episode, the

English-language Wikipedia

page

on

the game currently cites, of all things, a 2006

book published by Cardoza:

‘Eric Schiller wrote, “others say they were just

paying off their wagers”.’

C.N. 12063 referred to the existence of a Wikipedia

project group created to ‘improve information on

chess-related articles’. The project group states:

‘Print sources are generally considered reliable,

but certain authors such as Eric Schiller and

Raymond Keene have a reputation for unreliability.’

12130. Edgar

Pennell and the skewer

Recent C.N. items referring to Wikipedia are a

reminder that its entry on the chess

term

skewer does not currently name the man who

coined it, Edgar

Pennell.

The photograph on page 275 of CHESS, 14 April

1937 (C.N. 8894) had already appeared widely in the

press, in the United Kingdom and the United States.

From page 6 of the Liverpool Daily Post, 16

June 1936:

The originator (probably by 1937) of the chess word

‘skewer’ was shown in the Liverpool Daily Post,

30 January 1939, page 6:

Pennell’s name was seldom seen in chess literature,

although page 153 of the May 1955 BCM reported

that in Cheltenham on 19 March, during the National

Chess Week, he had participated in a Chess Brains

Trust, alongside C.H.O’D. Alexander, J.M. Aitken and

J. Bronowski. The subjects included ‘Is chess a waste

of time?’ and ‘Why are lady chessplayers outclassed by

men, even in Russia?’.

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘An article in the Staffordshire Sentinel

(31 January 1939, page 6) referred to Edgar

Pennell as “a native of Bucknall”. This is

Bucknall, Staffordshire, near Stoke-on-Trent.

Since the birth of an Edgar Pennell was registered

in the district of Stoke-on-Trent in the third

quarter of 1902 (G.R.O., birth indexes, volume 6b,

page 192), and the death of an Edgar Pennell was

registered in 1985 in the district of Windsor and

Maidenhead (death indexes, volume 19, page 68)

which included the date of birth of 21 June 1902,

there is no doubt that this is the skewer man.

Edgar Pennell’s birth certificate shows that he

was born on 21 June 1902 at Eaves Lane, Bucknall;

his parents were Ernest Pennell, a schoolmaster,

and Bessie Ethel Pennell (formerly Mann). The

birth was registered on 21 July 1902.

His marriage to Leah Bailey was registered

during the first quarter of 1927 in the district

of Liverpool (source: G.R.O. marriage indexes,

volume 8b, page 234).

Edgar Pennell’s death was registered on 3 June

1985 in the district of Windsor and Maidenhead

(volume 19, page 68). His death certificate shows

that he died on 2 June 1985 at Upper Orchard, Mill

Lane, Cookham, Berkshire. His date and place of

birth were given as 21 June 1902 and Bucknell [sic],

Staffordshire. He was a retired school teacher.

The informant was named as Alwin Gilbert Allen,

whose qualification was “Causing the body to be

cremated”, and his usual address was The Bungalow,

Odney Common, Cookham, Berkshire.

The cause of death was entered as:

“Myocardial Infarction

Coronary Atheroma

Certified by Julia Mercer MBBS.”

His wife was a couple of years younger and died

on 24 November 1992 at Sandpipers Residential

Home, Worster Road, Cookham, Berkshire. Her will

was proved at Winchester on 29 December 1992, the

estate not exceeding £125,000.’

12131.

Rubinstein photograph

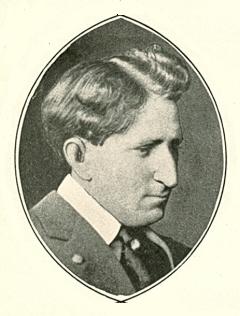

We are authorized to show this portrait of Akiba

Rubinstein which is held by the Jewish

Museum

of Belgium:

12132.

Max Ritter von Gomperz

Michael Lorenz (Vienna) has provided an extract from

‘a balance sheet in the probate file of the

Austrian banker, industrialist and chess patron Max

von Gomperz (1822–1913) which shows that every month

he paid 174 Kronen in support of chessplayers’:

Larger version

Our correspondent draws attention to the obituary and

photograph of von Gomperz on pages

290-293 of the October-November 1913 Wiener

Schachzeitung.

12133.

The Mouthless Dead

The latest book featuring the Wallace

murder

case is an elegant novel by Anthony Quinn, The

Mouthless Dead:

The phrase ‘the mouthless dead’ is from the first

line of a posthumously published poem

by Charles Hamilton Sorley (1895-1915).

12134.

Prison warders

In the United Kingdom a number of individuals

convicted of capital offences played chess against

prison warders. The following appeared under W.H.

Wallace’s name on pages 8-9 of John Bull, 14

May 1932:

‘I see clearly in the freedom of my bedroom the

faces of the warders of the death-watch at the

condemned cell – the faces that will never leave me,

day or night, until the end comes.

I see myself again playing chess with them. ... I

wonder – do they still play chess? I taught them.’

Wallace described on page 19 of John Bull, 30

April 1932 how he was publicly perceived:

‘I was not only “the man Wallace” but “another

Rouse”.

He was referring to Alfred Arthur Rouse (1894-1931),

the ‘blazing car murderer’. A report about Rouse on

page 1 of the (London) Evening Standard, 7

March 1931 stated:

‘In the condemned cell he is guarded day and night

by two warders. During the daytime he has exercised

in the small prison yard and in the cell he plays

draughts and chess with the “death guard”.’

From the front page of the (Sunday) People, 8

March 1931:

Page 6 of the Evening Express (Liverpool), 7

March 1931 described Rouse as ‘an expert chess and

draughts player’. Journalists often misapply ‘expert’

and ‘champion’ to prisoners and prodigies.

Another case was John George Haigh (1909-49), the

‘acid bath murderer’. From page 3 of the Daily

Herald, 21 July 1949:

Chess

and

Murder mentions Neville George Clevely Heath

(1917-46), who ‘played a certain amount of chess with

the warders, two of whom were in his cell day and

night’. Concerning William Joyce (1906-46), C.N. 11446

related that, before being hanged for high treason,

‘in the condemned cell he has played chess with the

prisoner officers’.

From page 1 of the Evening Despatch

(Birmingham), 31 August 1948:

The article was on pages 314-315 of the September

1948 BCM:

Acknowledgement for

the BCM scan: Cleveland Public Library

12135.

Close and closed

Whether referring to openings, games or positions,

the terms ‘close’ and ‘closed’ tend to be vague and

interchangeable. With openings, for instance, they

have traditionally been applied when 1 e4 did not

occur – in contrast to 1 e4 e5 (open games) and 1 e4

answered by a move other than 1...e5 (semi-open

games). However, would many writers nowadays

specifically classify 1 d4 f5 2 e4, for example, as a

‘close’/‘closed’ game? To what end?

When a position is to at least some extent blocked,

‘closed’ may seem more logical than ‘close’, with the

bonus of avoiding ambiguity, since ‘it was a close

game’ normally suggests a narrow victory.

Where is the best guide to such terminology, and are

there languages with concepts or nuances unknown in

English?

12136.

Lasker on Maróczy

From Emanuel Lasker’s column in the New York Evening

Post, 2 May 1908, page 9:

‘Maróczy has the emotional nature of the Magyar,

and is therefore as variable as his moods. He can

play all styles, the highest and the lowest, and

neither his upper nor his lower limits have yet been

determined. Hence he is somewhat of a riddle, that

could be solved only if he pitted himself against

the foremost masters in match play, but he

resolutely declines to do so. Perhaps he likes to

remain a mystery.’

12137.

Abrahams v Maróczy

A good copy of this photograph would be welcome:

Evening Express

(Liverpool), 6 January 1930, page 5

12138.

Gerald Abrahams

The shot of Gerald Abrahams in C.N. 12137 is a

reminder of an unresolved matter in C.N. 10985: given

that Abrahams was born in 1907, how can the National

Portrait Gallery, London put ‘1933’?

12139.

Abrahams on Yates

On page 6 of the Liverpool Post & Mercury,

14 November 1932 Gerald Abrahams paid tribute to F.D.

Yates:

From page 6 of the following day’s newspaper:

Yates’s loss to Sir George Thomas in Canterbury

(1930) has been widely published. For a group

photograph of participants in the tournament, see C.N.

4350.

12140.

Staunton’s early life

C.N.s 12116 and 12127 prompt an addition to Predicaments

for

Chess Writers: the task of writing just a

factual line or two about Howard Staunton’s early

(pre-chess) years.

12141.

Staunton and friendship (C.N. 12117)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘In C.N. 12117, the chess columnist William

Mitcheson stated that Howard Staunton “threw off”

friendships when they were no longer of service to

him. No evidence for his assertion was offered,

and no examples were provided.

It cannot be doubted that Staunton made enemies,

but the same could be said of other top players

who have been world champion or regarded as the

world’s best, or who have achieved great fame. The

examples of Steinitz and Alekhine spring to mind,

while Lasker and Capablanca acquired reputations

for making challenges difficult to mount,

resulting in tensions. Is there not something

special about the position of a champion which

provokes envy, rivalry and hostility? They are

there to be shot at.

In the case of Staunton, he was, in addition, a

forthright man. The art critic Thomas Jefferson

Bryan, in comparing him with Saint-Amant,

preferred Staunton’s openness and made the

following observation:

“Mr Staunton cares not to appear other than he

is. I make no pretensions to etiquette, but common

sense induces me to prefer his sincerity – and I

confess his mode of behaviour is the more pleasing

to me – for we cannot accuse him of carrying his

politeness to an undue excess.” (Source: Chess

Player’s Chronicle, 1846, page 147.)

In a letter to the City of London Chess

Magazine (January 1875, pages 12-13), von der

Lasa referred to Staunton’s own remarks about his

associations with five notable chess figures:

“Staunton’s letter of November last [1873]

was altogether written in a most friendly tone,

and spoke likewise in affectionate terms of other

players. ‘I was sorry’, he wrote, ‘to lose Lewis

and St Amant, my dear friends Bolton and Sir F.

Madden, and others of whom we have been deprived,

but for Jaenisch I entertained a particular

affection, and his loss was proportionately

painful to me. He was truly an amiable and an

upright man.’”

In the case of the problemist Reverend

Horatio Bolton, a Norfolk clergyman, he had

been a friend since at least 1840, when the two

contested a correspondence match, and he was

referred to as a friend in a letter as late as

1873, the year of Bolton’s death.

Von der Lasa acknowledged that Staunton was