Edward Winter

A comment about Sultan Khan by Gerald Abrahams on page 223 of the August 1952 BCM:

‘An obscure Indian from a Punjab village held his own with the best players in Europe without ever making a surprising move.’

(2616)

With respect to masters’ preferences regarding the minor pieces, Gerald Abrahams wrote on page 63 of Teach Yourself Chess (London, 1951):

‘The late Alexander Alekhine, a player whose style lent itself to combinations on the crowded board, seemed to prefer the knight.’

Such generalities are easily put forth, and this one seems particularly questionable.

(2732)

One of the few players to have boasted of producing an ‘immortal’ game was Gerald Abrahams, in two of his books. Pages 246-247 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974) and page 136 of Brilliance in Chess (London, 1977) had the heading ‘An Immortal’, plus almost identical notes to his well-known game against (R.S.?) Thynne, ‘Liverpool, 1930’:

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 Nbd7 6 Nf3 O-O 7 Rc1 c6 8 Qc2 Re8 9 Bd3 dxc4 10 Bxc4 Nd5 11 Ne4 Bxg5 12 Nexg5 N5f6 13 Kf1 h6 14 h4 hxg5 15 hxg5 e5 16 gxf6 Qxf6 17 Qh7+ Kf8 18 Nh4 Nb6 19 dxe5 Qxe5 (‘In answer to 19…Qxe5 I had been saving something up. In fact I’d invited an old gentleman who was pottering towards the door, to stay, because in a few minutes I’d have a good move for him to see.’)

20 Qg8+ (‘And the rest is history.’) 20…Ke7 (‘If 20…Kxg8 21 Ng6 forces mate.’) 21 Qxf7+ Kd8 22 Ng6 Qxb2 23 Rd1+ Bd7 24 Qxe8+ Resigns.

Abrahams also gave ‘Liverpool, 1930’ when presenting his 20th move (‘one of very few moves known to the Author which merits an exclamation mark although the main variation is only two moves deep’) on page 43 of The Chess Mind (Harmondsworth, 1960), whereas on page 39 of the original hardback edition (London, 1951) no players’ names or occasion were specified.

But Abrahams was not always the most rigorous author for dates and other ‘details’, so is ‘Liverpool, 1930’ correct? When Chernev gave the score on pages 537-538 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess he put ‘Liverpool, 1929’, whereas the two Informant books on middle-game combinations (pages 191 and 284 respectively) had ‘Liverpool, 1932’. On page 28 of The Brilliant Touch (London, 1950) Walter Korn stated ‘Liverpool C.C. Championship, 1936’.

(3158)

David McAlister (Hillsborough, Northern Ireland) reports that Gerald Abrahams’ game against Thynne was published in the Belfast News-Letter of 1 February 1934. Our correspondent comments:

‘While it does not help with time and place, the date of publication can at least rule out Korn’s attribution. Also, the initials R.S. are given for Thynne.’

We now seek pre-1934 cases of the game being published.

(3167)

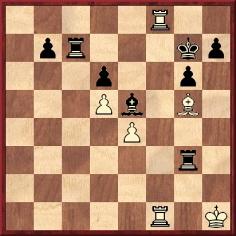

White to move

We have not yet quoted C.J.S. Purdy on the game. He annotated it on pages 315-316 of the Australasian Chess Review, 12 November 1936 with this introduction:

‘We all enjoy bombshell moves. The 20th move in this game makes a loud enough explosion for anybody. Abrahams specializes in bombing.’

Purdy gave 20 Qg8+ three exclamation marks.

(11959)

Addition on 25 May 2025:

David McAlister has found the game-score on page 5 of the 19 July 1930 edition of the Northern Whig and Belfast Post:

We now note this earlier occurrence, in Brian Harley’s column on page 25 of The Observer, 25 May 1930:

The practice of repeating annotations from elsewhere was discussed in C.N. 12160, on the basis of the Abrahams v Thynne game.

From W.D. Rubinstein (Aberystwyth, Wales):

‘In Gerald Abrahams’ essay “Assessment of Lasker”, originally (it seems) a Third Programme BBC broadcast but reprinted on pages 145-147 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974), there is this paragraph, in a review of Hannak’s biography of Lasker:

“Lasker was terribly lazy. The authors [sic] of the book do not say this, but it is written clearly between the lines. (With more energy he would have been a great mathematician.) I have it from Amos Burn and Gunsberg and Mieses that, in his early tournaments, Lasker was in the habit of driving up to the hall in a barouche or droshky, in order to find himself with 20 moves to make in as little as five minutes. I have it from Levenfisch that he showed the same inertia when they gave him opportunities for mathematical research at Moscow. He was content to ‘throw out ideas’.”

This does not sound like Lasker. Did he really arrive at tournaments with five minutes to spare? Abrahams was a barrister and a talented chess writer. He was born in 1907, but did he really have anecdotes like this from Amos Burn?’

(3673)

At Bournemouth, 1939 Gerald Abrahams finished last with a single point, derived from a long win (available in various databases) against Mieses in the second round. CHESS, October 1939 (page 3) reported that during the game Mieses refused a draw five times. Do readers know of comparable cases of multiple refusals?

(3739)

In Bournemouth on 21 August 1939 Abrahams lost a game (1 d4 b5) in 12 moves against Max Euwe, as reported at the start of the chess column on page 7 of the (London) Evening News the following day:

See The Chess Moves 1 b4 and 1...b5.

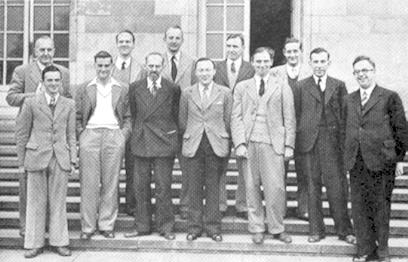

A group photograph taken during the Nottingham, 1946 tournament and given opposite page 49 in the book on the event published the same year by CHESS, Sutton Coldfield:

Front row, left to right: R.G.

Wade, F. Parr, W. Winter, R.F. Combe, C.H.O’D. Alexander, H.

Golombek, G. Abrahams

Behind: G. Wood, R.J. Broadbent, P.S. Milner-Barry, A.R.B.

Thomas, B.H. Wood

This was taken at the same place as one of the most famous chess group photographs: Nottingham, 1936.

One of Abrahams’ best-known games is his victory over J. Cukierman in section B of the general congress at Nottingham, 1936. It was included in Alekhine’s tournament book.

A photograph, from the 1929 British Championship in Ramsgate, is added here, gleaned from page 162 of the September-October 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

Left to right, standing: W.H.M.

Kirk, W. Winter, J.A.J. Drewitt, Rev. F.E. Hamond, T.H. Tylor,

R.P. Michell, J.H. Morrison

Seated: A. Eva, H.E. Price, M. Sultan Khan, G. Abrahams, W.A.

Fairhurst

(4059)

An item in Chess Autographs:

Below is a page from one of our copies of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters by Edward Lasker (New York, 1951), inscribed by the players at Hastings, 1951-52 (plus Sämisch, a participant in the Premier Reserves tournament):

In order: L. Schmid, D. Yanofsky, L. Barden, D. Hooper, H. Golombek, G. Abrahams, A.R.B. Thomas, S. Popel, F. Sämisch, S. Gligorić and J.H. Donner.

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) offers some jottings on Gerald Abrahams at Bad Gastein, 1948:

‘Pages 325-326 of the September 1948 BCM have the game Danielsson (misspelt “Danielson”) v Abrahams played at Bad Gastein, 1948: 1 Nf3 f5 2 g3 Nf6 3 Bg2 c6 4 O-O d6 5 d4 Qc7 6 c4 e5 7 Nc3 Be7 8 dxe5 dxe5 9 e4 O-O 10 exf5 Bxf5 11 Qe2 Nbd7 12 Re1 Rae8 13 Bg5 h6 14 Bxf6 Bxf6 15 Ne4 Bxe4 16 Qxe4 Nc5 17 Qc2 e4 18 Nd2 Bd4 19 Re2 e3 20 Nf3 exf2+ 21 Kf1 Be3 22 b4 Na6 23 Qb3 Qe7 24 Rd1 Qe6 25 a3 c5 26 b5 Nc7 27 g4 Qe4 28 Rd3

28...Rxf3 29 Bxf3 Qxf3 30 Rexe3 Qh1+ 31 Kxf2 Ne6 32 Qd1 Qxh2+ 33 Ke1 Rf8 34 Rf3 (The ChessBase Megabase has a different move order: 32...Rf8 33 Rf3 Qxh2+ 34 Ke1.) 34...Nf4 35 Rxf4 Re8+ 36 Kf1 Qxf4+ 37 Kg1 Re4 38 Rd8+ Kh7 39 Qd3 Qxg4+ 40 Kh1 Qh5+ 41 Kg2 Qg6+ 42 Kf3 Qf5+ 43 Kg3 Rg4+ 44 Kh3 Qxd3+ 45 Rxd3 Rxc4 46 Rd7 Rc3+ 47 Kh4 Rxa3 48 Rxb7 c4 49 Kh5 c3 50 Rc7 Ra4 51 b6 c2 52 b7 c1(Q) 53 White resigns.

When I first came across this game, many years ago, I was struck by the opening moves employed by that brilliant (and sometimes erratic) player Gerald Abrahams. The formation he uses in the Dutch Defence is usually referred to as the Hort-Antoshin Variation, which I think was introduced by Hort around 1960, with Antoshin later contributing to the underlying ideas.

Described as “an extremely interesting game”, it was annotated in the Games Department of the BCM, conducted by C.H.O’D. Alexander, with the following remark after move 27:

“Abrahams plays the ending somewhat maliciously, holding out tempting hopes of stalemate to his opponent only to disappoint him unkindly at the end.”

There are two other games by Abrahams from Bad Gastein in the 1948 BCM volume, against Canal and Tóth. Both are wonderful examples of his sharp style, and page 288 of the August issue stated that the game against Tóth earned Abrahams a brilliancy prize. However, on page 259 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974) and page 137 of Brilliance in Chess (London, 1977) Abrahams himself wrote:

“The Bad Gastein organizers promised me a brilliancy prize for this, but all I got was a free copy of the tournament book.”’

(4220)

A group photograph (Canterbury, 1930) was published on page 205 of the June 1930 BCM:

Standing (left to right): H.E.

Price, E. Spencer, W. Winter, G. Abrahams, A. Seitz

Seated: F.D. Yates, V. Menchik, Sir George Thomas

(4350)

Justin Horton (Huesca, Spain) wonders who was being referred to by Gerald Abrahams in the following paragraph from page 115 of his book Not Only Chess (London, 1974):

‘The computer, however, has no judgement, except the arithmetical. They say of the computer that if it has to choose between two clocks, it prefers the one that has stopped to the one that loses a second a day, because the former is accurate twice a day and the other is only accurate after many days. In this the computer resembles an unlamented Times correspondent who reviewed the position at the adjournment in a Hastings Congress. On each of five boards he predicted victory for the player with the pawn to the good. In every case that player lost.’

The name of E.S. Tinsley naturally comes to mind (see pages 245 and 272 of Chess Explorations), but we know nothing about the specific accusation made by Abrahams.

(4557)

Below is the author’s inscription in one of our copies of Test Your Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1963):

‘A book of chess problems by Britain’s leading expert’ was the dust-jacket’s daring encomium.

(4732)

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) writes:

‘On page 9 of his book Richard Réti, šachový myslitel (Prague, 1989) Jan Kalendovský mentioned that Richard Réti was born in 1889 in Pezinok to Samuel Réti from Hlohovec and to Anna, née Mayerova, in a Pezinok Jewish family.

Richard’s brother Rudolph (1885-1957), a noted Viennese concert pianist, composer and musicologist, emigrated to the United States in the late 1930s and subsequently became an American citizen. His papers and the chess manuscripts and notes of Richard Réti are held at the Library of Congress.

Richard Réti is listed as a Jewish chessplayer in the Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 1973) – see pages 401-409 of volume five and page 103 of volume 14 – but the chess editor, Gerald Abrahams, did not provide supporting references for his text.’

(4856)

‘Be more considerate to small boys.’ That request was made to Alekhine by Gerald Abrahams in 1936, as related on pages 135-136 of his book Not Only Chess (London, 1974).

At a simultaneous display in Liverpool in autumn 1923 Abrahams, then aged 16, was the last surviving player:

‘And there was Alekhine, standing over the board, insisting on instantaneous replies. He thought, then made his move, rapped sharply on the table and made impatient sounds in Russian.

The position was hard. Pawns wedged with pawns, and my king bishop and knight, endeavouring to be on guard at all moments against his king, and two fantastically wheeling knights. After 12 lightning moves under these conditions the boy went wrong, found a pawn indefensible, and resigned. The grandmaster swept the pieces aside brusquely, and stalked away. He was, let me emphasize, entirely within his rights.’

After describing how differently Capablanca later behaved towards him in similar circumstances, Abrahams related that at Nottingham in 1936 Alekhine’s wife (‘a delightful American lady’) required assistance with a visa renewal.

‘Alekhine asked me to oblige, and I gladly did so. He said, “If I can ever do anything for you, please ask me.” I replied, “You can do something for me.” He raised an interrogative eyebrow. I said, “Be more considerate to small boys.” The frozen blue eyes stared at me for some seconds. “Yes”, he said, I remember, Liverpool 1923. You had pawns, bishop and knight against my pawns and two knights. You should have drawn that game.”’

Although Abrahams stated that Alekhine faced 60 opponents, the master’s score given on page 403 of the November 1923 BCM and page 197 of the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine was +24 –1 =6. The exhibition took place on 29 September 1923.

Gerald Abrahams

(5127)

From pages 24-25 of Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974):

‘... Cold-blooded gamesman-planning is rare. But I have one pretty example. At my first British Championship, [at Ramsgate] in 1929, a friend of mine – who is a magnificent analyst and celebrated in the chess world – found himself in a very bad position. But there was a way out. Given that his opponent (a very strong player) did not see the threat, it was possible, with a series of sacrifices, to achieve stalemate. But he had to include in his play a clearly inadequate move, which would inevitably warn his opponent. After all, one plays chess on the assumption that the opponent sees everything. (That is why the word “trap” is not a good chess term.) But my friend devised a psychological trap. He sat and looked at the board with a despairing face until he was well and truly in time trouble. Then he fumblingly made the crucial moves. His opponent, tempted to a little gamesmanship himself, was playing very quickly. Quick came the erroneous capture. Even quicker came the series of sacrifices and, while the flag was tottering, stalemate supervened. Now could he have improved on things in the following way: touched the piece, taken his hand away, and let himself be compelled to move the piece at random? No, he had thought of that, but dismissed it as sharp practice.’

Abrahams then gave the relevant position:

‘Time control at move 40. At move 31 Black has played R-Kt6, a good move, because, if either rook guards the bishop, RxB wins.’

Play continued: 32 Bd2 Rg3+ 33 Kh1 Rxh3+ 34 Kg1 Rd3 35 Bc1 (‘Leaving himself less than half a minute on his clock.’) 35...Rc7 36 Bg5 (‘Finger staying on his clock; and Black falls for it.’) 36...Rg3+ 37 Kh1

37...Rxg5 38 R1f7+ Rxf7 39 Rxf7+ (‘Forcing stalemate or perpetual check.’).

Abrahams did not name the players, but the position after White’s 37th move was given on page 346 of the September 1929 BCM. W.A. Fairhurst was White against T.H. Tylor.

For similar deeds, see Chess Cunning, Gamesmanship and Skulduggery.

Concerning the famous Flohr v Grob position (C.N.s 4309 and 4382) in which White mistakenly resigned:

C.N. 4309 asked about the first publication of the above erroneous diagram (erroneous because, in addition to the misplacing of the queen’s-side pawns, the pawn at f4 should be white).

Richard J. Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) notes that the diagram appeared on page 13 of the first edition of Gerald Abrahams’ Test your chess (London, 1963). The solution on the following page was:

Our correspondent remarks that 6...f2 is an oversight, since 7 Qxf2 gives check. The 1975 edition of Abrahams’ book corrected the sequence to 5 Qd5+ Kg6 6 Qe4+ Bf5, and Black wins.

(6482)

‘[Capablanca] had a better conceit of himself than had Alekhine, but was a much nicer and much better-liked man. Alekhine was qualified as a lawyer and had a powerful intellect. He was the only man I ever met who was arrogant without being conceited. What do I mean by arrogant? He treated inferiors as if they were inferiors – but he very rarely made Capablanca’s mistake of taking his own powers for granted.’

Source: page 139 of Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974).

(7179)

‘... a good attacking player who allows the game to simplify usually has in mind some ultimate movement which destroys the illusion of equality.’

Source: Test Your Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1963), page 92.

(7432)

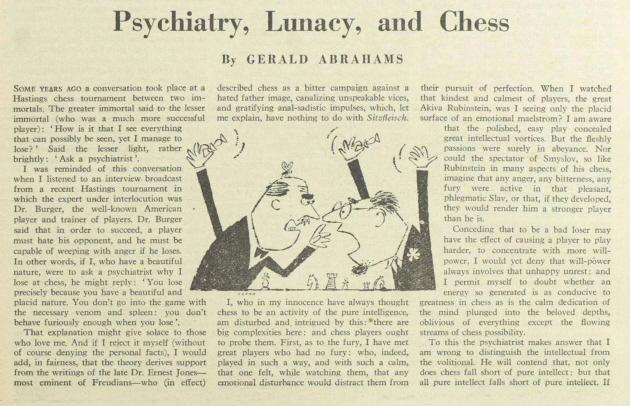

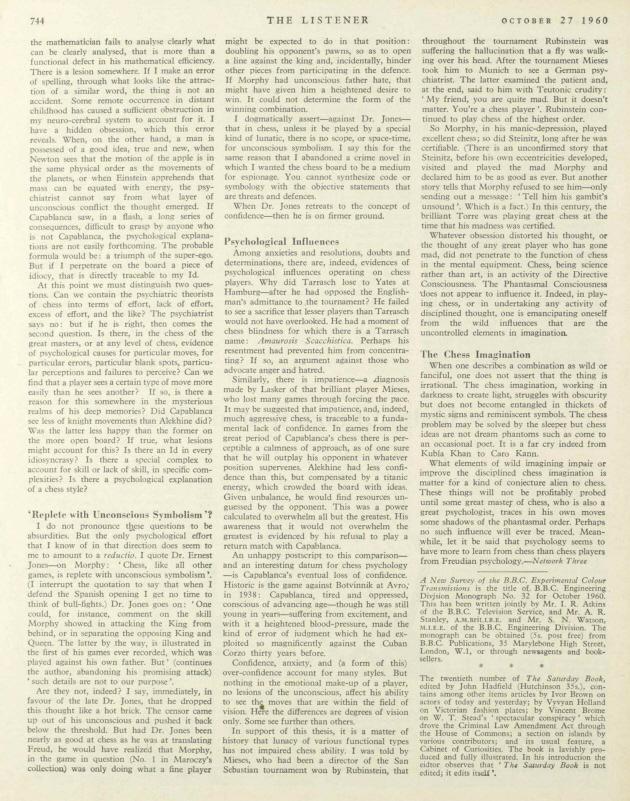

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has supplied an article by Gerald Abrahams from pages 743-744 of The Listener, 27 October 1960:

The text is markedly different from the article of the same title reproduced on pages 26-36 of Abrahams’ book Not Only Chess (London, 1974).

(8139)

See also Chess and Insanity.

An example of Gerald Abrahams’ unmistakable prose style as he tackles a complex topic:

‘... The author ventures the suggestion that there is a lot of nervousness among the players of Black – a nervousness which is unjustified.

If White is a better colour than Black, then let us all give up chess!

What is the truth of the matter? First, White has an initiative. In certain well-recognized lines of play, which Black may feel it necessary to adopt (e.g. defences to the López), that initiative lasts a long time. But an initiative must not be confused with an advantage.

There is no opening in which White, without sacrificing unsoundly, can prevent Black achieving full development. When that is achieved, it may well be a better development than White’s, because it is a subtler one; in the interstices of a rigid position.

But Black must be patient; and Black has more work to do in the early stages, while White has a few more possibilities in his field of choice. Players, therefore, prefer White through laziness. They prefer not to have to work too hard in the opening stages. But in reality White too must work. To preserve an initiative as long as possible, without incurring strategic commitments that may prove undesirable, is at least as hard a task as playing a process of development without full initiative. There are a few players, the author included, who actually like Black, precisely because the play for “equalization” is there to be found, and find its exploitation fascinating. Two propositions, certainly, are true: (1) Nobody ever beat a better player through having White. (2) Nobody ever lost merely through having Black. If it be said that White can so play as to have drawing chances against the best, the answer is: play against the best – and see!’

Source: page 275 of The Handbook of Chess and The Pan Book of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965).

(8194)

C.N. 809 gave an observation from Anthony Saidy (Santa Monica, CA, USA):

‘This error [an inaccurate reference to Moscow, 1914] also appears in Abrahams’ Brilliance in Chess together with his gratuitous re-defining of “brilliance” to comply with that everyday definition of e.g. a “brilliant” mind. Why so ponderous a treatise with such disparate and heterogeneous examples of good play?’

We added a comment of our own:

Abrahams’ The Chess Mind is a first-rate work. Brilliance in Chess is just one more example of a writer over-estimating the number of books inside him.

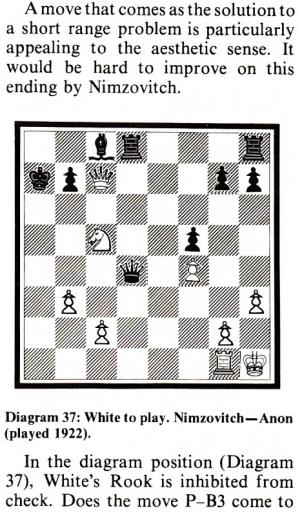

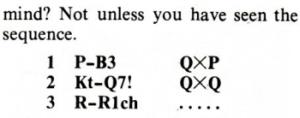

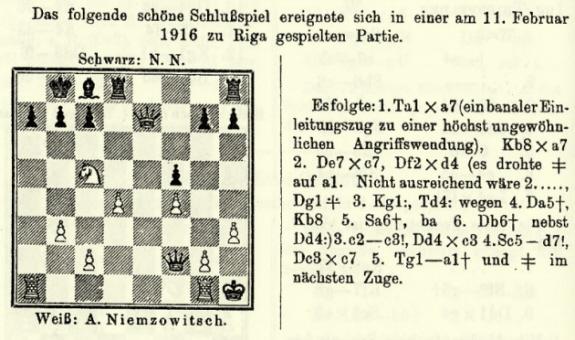

From page 33 of Brilliance in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1977):

This attractive finish occurred not in 1922 but in 1916, and was published on page 136 of the June 1918 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

(8676)

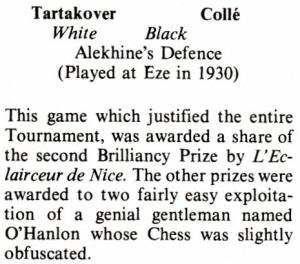

The carelessness of Abrahams’ Brilliance in Chess is illustrated by the heading of a Tartakower v Colle game on page 44:

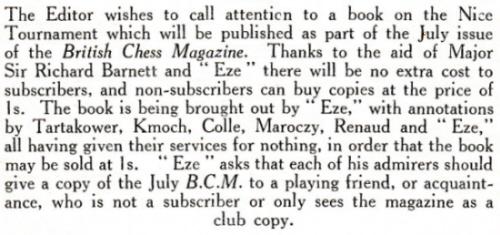

The oddest error is the statement that the game was ‘played at Eze in 1930’. The venue was Nice, and, as noted on page 196 of the June 1930 BCM, a tournament book was brought out by ‘Eze’:

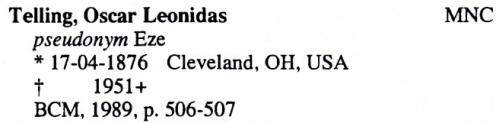

On page 353 of the September 1981 BCM Brian Reilly mentioned that ‘Eze’ was the pseudonym of O. Telling of Denver, CO, USA, and page 751 of the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige gave this entry:

(8677)

From C.N. 9051:

The Eze/Nice confusion, which has yet to be explained, recurred on page 84 of Abrahams’ book, where he explicitly wrote:

‘In a tournament at Eze, in the South of France, in 1930, the best player was Tartakower ...’

He then gave two further positions from the event, Colle v O’Hanlon and O’Hanlon v Znosko-Borovsky. The diagrams were respectively labelled ‘Eze 1930’ and ‘Played Eze’. Abrahams wrote that the two games received brilliancy prizes, from a newspaper which, as he had already done on page 44, he called L’Eclairceur de Nice. L’Eclaireur de Nice is/would be correct.

After a few general comments about brilliancy (‘Let us not call every sacrifice brilliant’) Abrahams gave a footnote:

‘There must be something in the air of the South of France because in 1974, at Nice, they awarded the first brilliancy to an English Master (certainly a fine player) who made a sacrifice on K6 for which the board was screaming – and they rejected harder pieces of play.’

Even today, when technology increasingly encourages people, including the uninformed and illiterate, to share their opinions about tout ce qui bouge, it may still seem rather inelegant to dispute brilliancy-prize decisions. The case referred to in Abrahams’ footnote was Michael Stean’s victory over Walter Browne, a game which Harry Golombek published on page 235 of A History of Chess (London, 1976).

Improbable as it may seem today, CHESS often used to adopt a critical, demanding attitude to new books. For example, below is a review of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951) on page 118 of the March 1952 issue of B.H. Wood’s magazine:

In contrast, The Chess Mind was received positively by J.M. Aitken on pages 12-13 of the January 1952 BCM. The first paragraph:

‘This work breaks fresh ground in chess literature. It is not a textbook on the game, though much of the book, particularly the numerous examples, would be interesting and instructive from this angle, too, to the player of some experience, though not the absolute tyro; it is a study of what happens when chessplayers (more particularly the chess masters) think. The subject is by its very nature not an easy one to analyse and expound; hence the book necessarily deserves – and repays – concentrated attention; but the style does not – as in some hands it might have done – add to the inherent difficulties. It is throughout light, racy and frequently aphoristic, and is mercifully free from any suspicion of philosophic jargon.’

Fred Reinfeld was even more enthusiastic on page 182 of How To Get More Out Of Chess (New York, 1957):

‘The Chess Mind, by Gerald Abrahams, is to my way of thinking one of the very best, and certainly one of the most original, books ever written on chess. Of making chess books there is no end, but few are as meaty and brilliantly written as this one. Such chapters as Vision in Chess; Common Sense and the Intrusion of Ideas; Imagination: Its Use and Abuse; How Battles are Won and Lost are unique in chess literature. One of the finest books ever written on chess.’

The Chess Mind subsequently appeared in paperback editions, widely and inexpensively available today from second-hand booksellers.

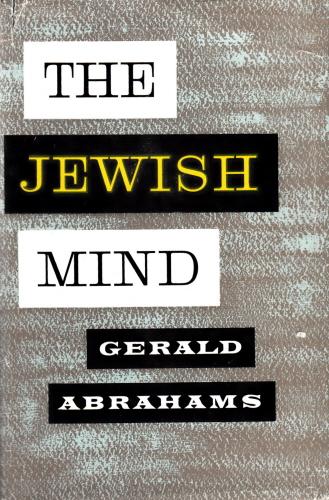

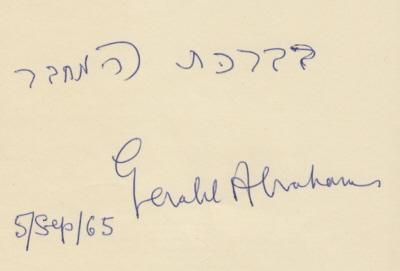

As mentioned in Chess and the Wallace Murder Case, Abrahams also wrote The Legal Mind (London, 1954). He was, furthermore, the author of The Jewish Mind (London, 1961), and our collection includes a copy inscribed by him:

The Jewish Mind has a few references to chess in the footnotes, including the following on page 354:

(8824)

See also Chess and Jews.

From page 41 of the London, 2007 edition of Kasparov’s How Life Imitates Chess:

In the US edition (New York, 2007) this ‘Tartakower quote’ is in the heading to Chapter 3, on page 36. But did Tartakower make such a remark and, if so, where and when?

The earliest citation that we can currently offer is nothing better than a ‘once’ reference in an article about Fischer by Harold C. Schonberg on page SM63 of the New York Times, 23 February 1958:

The article was reproduced on pages 49-55 of The Joys of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1961), still with the initial T. for Tartakower’s second forename. Schonberg also ascribed the quote to Tartakower on page 160 of Grandmasters of Chess (Philadelphia and New York, 1972), and it is regularly seen in chess books, without a source. For instance, Gary Lane used it to fill a corner on page 57 of Prepare to Attack (London, 2010).

In his entry on aphorisms on page 16 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977) Wolfgang Heidenfeld included the following:

‘“Whereas the tactician knows what to do when there is something to do, it requires the strategist to know what to do when there is nothing to do” (Abrahams).’

Heidenfeld gave no source, but we have found the remark on page 150 of Abrahams’ book Teach Yourself Chess (London, 1948), although with ‘strategian’ instead of ‘strategist’.

Furthermore, the following can be quoted from page 152 of The Handbook of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965):

‘At many stages of the game the general choice is available; what to do now that there is no coercion? Epigrammatically, it may be said: Tactics are what you do when there is something to do. Strategy is what you do when there is nothing to do. That isolation, however, is rare. Strategy is a feature, albeit unobserved, of most good tactical play. It is latent – not patent.’

(8833)

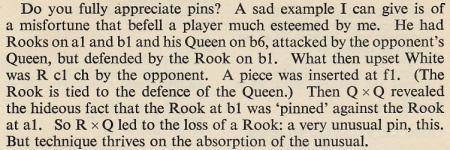

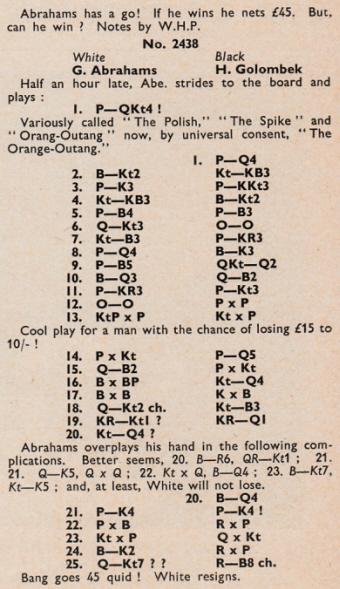

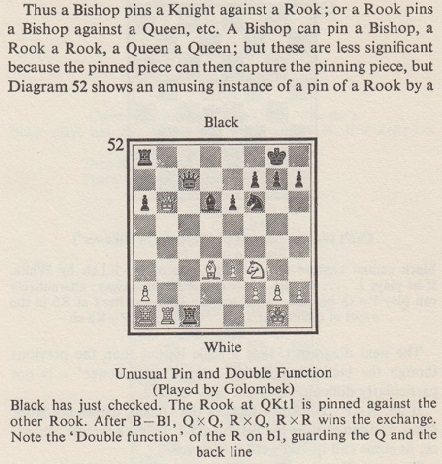

From page 215 of Technique in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1961):

The passage was referred to in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column on page 303 of the October 1965 BCM:

There was also a brief reference on page 359 of the December 1965 BCM.

Below is the finish as given on page 57 of the BCM, February 1948:

The game was ‘annotated’ by W.H. Pratten on page 121 of the February 1948 CHESS:

Although sometimes dated 1947, the game was played on 6 January 1948, as reported on page 7 of the Times the following day.

(8842)

As shown in C.N. 8842, this was the final position in Abrahams v Golombek, Hastings, 1948:

On page 67 of The Handbook of Chess (London, 1965) Abrahams gave a different position and named only Golombek:

(8913)

Source: page 133 of Teach Yourself Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1948).

Source: page 125 of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951).

Source: page 199 of Technique in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1961).

Source: page 92 of Test Your Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1963).

Source: page 8 of The Handbook of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965).

Source: page 49 of Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974).

Source: page 32 of Brilliance in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1977).

(8908)

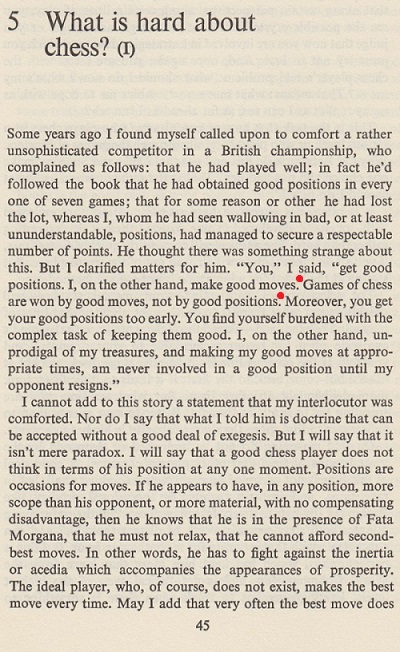

C.N. 8908 quoted from page 49 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974) Gerald Abrahams’ observation ‘Good moves win; good positions don’t win’.

On page 45 of the same book Abrahams cited a conversation with another player ‘some years ago’:

‘But I clarified matters for him. “You”, I said, “get good positions. I, on the other hand, make good moves. Games of chess are won by good moves, not by good positions. Moreover, you get your good positions too early. You find yourself burdened with the complex task of keeping them good. I, on the other hand, unprodigal of my treasures, and making my good moves at appropriate times, am never involved in a good position until my opponent resigns.”’

For the context, the full page is shown:

On page 106 of Not Only Chess Abrahams expressed the same sentiments in yet another wording:

‘The preparer got a good position. But good positions do not win games. Games are won by good moves, by many good moves, in conjunction with the opponent’s bad moves.’

Substantiation is sought of the most common version of the quote attributed to Abrahams, e.g. by Andrew Soltis on page 20 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008):

‘As Gerald Abrahams had said, “Good positions don’t win games. Good moves do.”’

(8912)

From page 219 of The Handbook of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965):

‘Most chess difficulties spring from pieces on awkward squares: there is something to be said for keeping to “natural” squares, if one knows which they are!’

(8925)

From pages 110-111 of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951):

‘It often happens that a line of play is too hard to analyse exhaustively within the time at the player’s disposal. He sees a few variations that are definitely in his favour, sees the possibility of one or two clever moves in the distance, sees no immediate refutation and, therefore, adopts the promising line, judging that the continuations will all be satisfactory.

In practice, the judgment that “something favourable will turn up” is true with a frequency that is inversely proportional to the player’s laziness. To the Micawbers of Chess there only happen bad results and occasional pieces of luck when an opponent plays particularly badly.’

(8933)

By definition, broad sweeps are liable to be wide of the mark. Perfectly worded bons mots are not necessarily perfectly true, but whatever the infusion of comic exaggeration, more than a mere kernel of truth is needed.

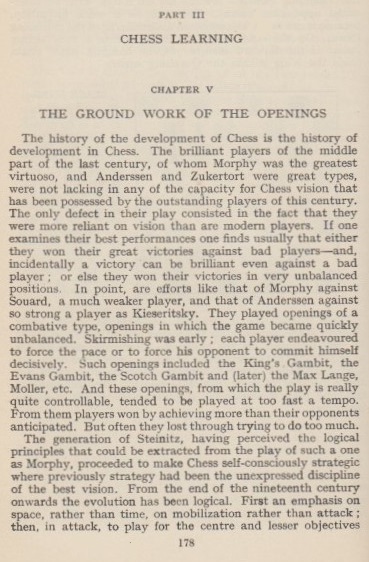

These intangibilities may be relevant to a remark by Gerald Abrahams on page 178 of Teach Yourself Chess (London, 1948). It is the first sentence of Part III (‘Chess Learning’), Chapter V (‘The Ground Work of the Openings’):

‘The history of the development of Chess is the history of development in Chess.’

Some may feel that this is a clever thought, cleverly phrased; others that the kernel of truth is all but undetectable. For our part, we continue to cite such snippets neutrally, leaving readers to make of them what they will.

In case it helps, below is the full page:

(8934)

In one of the best-known novels by Agatha Christie, Ten Little Niggers (London, 1939) – later retitled And Then There Were None and Ten Little Indians – the marooned characters are slow to realize that the name ‘U.N. Owen’ signifies ‘Unknown’.

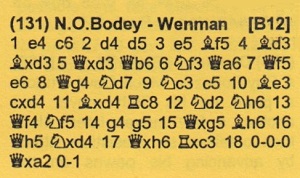

From page 54 of Hastings 1922/3 Margate 1923 Liverpool 1923 by A.J. Gillam (Nottingham, 1999), in the ‘Other Sections’ part concerning Liverpool:

As so often, Gillam mysteriously omitted to specify the source of the game, and he gave no sign of realizing that the name ‘N.O. Bodey’ was a whimsical pseudonym.

Ten players participated in the Liverpool tournament, and the pseudonym was in quotation marks on page 165 of the May 1923 BCM:

The quotation marks were retained by Jeremy Gaige on page 592 of volume four of Chess Tournament Crosstables (Philadelphia, 1974), which duly gave a reference to the above BCM table. Neither the quotation marks nor the source reference appeared on page 56 of Chess Results, 1921-1930 by Gino Di Felice (Jefferson, 2006).

Of the contemporary newspaper reports that we have seen, none revealed the identity of ‘N.O. Bodey’. The Scotsman of 2 April 1923, page 9, reported that the Major Tournament included ‘a Liverpool amateur who prefers to remain anonymous’. Page 6 of the Daily Telegraph, 6 April 1923 referred to ‘the gentleman who prefers to play under the euphonious pseudonym of N.O. Bodey’.

Page 55 of the Gillam booklet also had a sourceless snippet (moves 22-25) from the game between G. Abrahams and J. Jackson, but the full score of that first-round game can be shown here, from page 8 of the Scotsman, 3 April 1923 and page 9 of the same day’s edition of the Western Daily Press:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 c3 d5 4 Be2 dxe4 5 Qa4+ Bd7 6 Qxe4 Nc6 7 d4 h6 8 Be3 Qb6 9 Qc2 Rc8 10 Na3 cxd4 11 Nc4 Qc7 12 Nxd4 Na5 13 Nxa5 Qxa5 14 O-O Nf6 15 Rfe1 Bd6 16 h3 b5 17 Qd3 b4 18 c4 Ke7

19 c5 Bb8 20 Bf3 Qc7 21 g3 Rhd8

22 c6 Bxc6 23 Nxc6+ Qxc6 24 Qxd8+ Kxd8 25 Bxc6 Rxc6 26 Rac1 Kd7 27 Red1+ Nd5 28 Rc5 a6 29 Kf1 Bd6 30 Rxc6 Nxe3+ 31 fxe3 Kxc6 32 Kf2 a5 33 b3 Kc7 34 e4 Be5 35 g4 Kc8 36 Ke2 Kc7 37 Kd3 Kb7 38 Kc4 Kc8 39 Kb5 Bc7 40 Kc6 f5 41 gxf5 exf5 42 exf5 Bd8 43 Re1 Kb8 44 Re8 Kc8 45 Rh8 Resigns.

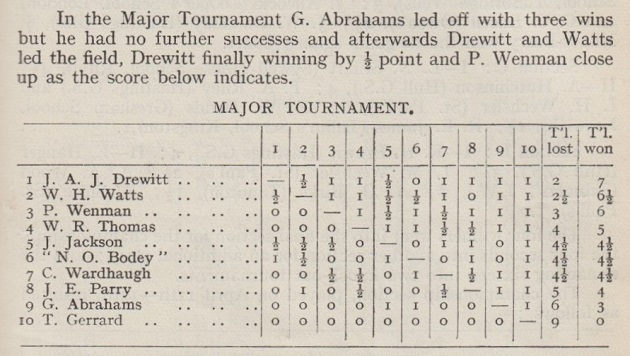

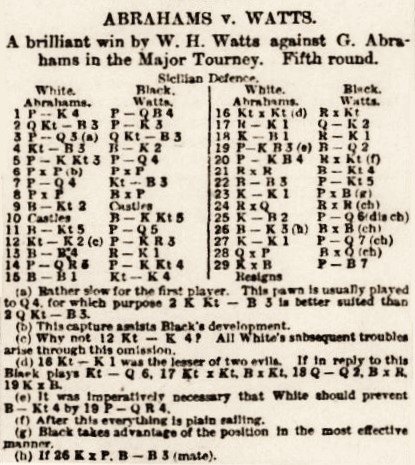

Later in the tournament, the 15-year-old Gerald Abrahams was defeated by W.H. Watts in a game which, though absent from the Gillam booklet, was published on page 234 of the Chess Amateur, May 1923, with notes from the Daily Telegraph. Below is what appeared in the newspaper on page 6 of its 6 April 1923 edition:

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 d3 Nc6 4 g3 Be7 5 Nf3 d5 6 exd5 exd5 7 d4 Nf6 8 dxc5 Bxc5 9 Bg2 O-O 10 O-O Bg4 11 Bg5 d4 12 Ne2 h6 13 Bf4 Re8 14 a3 g5 15 Bc1 Ne5 16 Nxe5 Rxe5 17 Re1 Qe7 18 Kf1 Re8 19 f3 Bd7 20 f4

20...Rxe2 21 Rxe2 Bb5 22 Bf3 g4 23 Ke1

23...gxf3 24 Rxe7 Rxe7+ 25 Kf2 d3+ 26 Be3 Bxe3+ 27 Ke1 d2+ 28 Qxd2 Bxd2+ 29 Kxd2 f2 30 White resigns.

The game had also been published on page 4 of the Yorkshire Post, 5 April 1923, which wrote of Abrahams: ‘He defends a losing game with extraordinary resource.’

As regards the Premier Tournament in Liverpool, won by Mieses ahead of Maróczy, Sir George Thomas and Yates, we add a further score which is absent from the Gillam booklet, the second-round game between A. Louis and F.D. Yates played on the morning of 2 April 1923:

1 c4 Nf6 2 d4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 f4 O-O 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 d5 Nb8 8 Bd3 e5 9 fxe5 dxe5 10 Bg5 h6 11 Be3 Qe7 12 O-O Ng4 13 Qe2 Nxe3 14 Qxe3 Nd7 15 Rae1 a6 16 b3 Nf6 17 Kh1 Bd7 18 Nh4 Ng4 19 Qg3 Bf6 20 Nf3 h5 21 h3

21...h4 22 d6 cxd6 23 Nd5 hxg3 24 Nxe7+

24... Kg7 25 Nxg6 Nf2+ 26 Kg1 fxg6 27 Re3 Rac8 28 Be2 Bd8 29 Nxe5 dxe5 30 Rxg3 Bb6 31 Kh2 Nxe4 32 Rd1 Bc6 33 White resigns.

Source: Western Daily Press, 4 April 1923, page 3.

(9881)

C.N. 9074 (see too ‘How Many Moves Ahead?’) showed an article by Vera Menchik on page 8 of the Daily Mail, 5 August 1927 in which she wrote:

‘When, for instance, I am asked how many moves I think ahead, I must, if I am truthful, give the same answer as that of the celebrated Czechoslovakian player Richard Réti: “Not even one move.”’

On page 265 of the 1 December 1947 issue of Chess World C.J.S Purdy introduced an article by Lajos Steiner, ‘How Many Moves Can You See Ahead?’, as follows:

‘Here is an entertaining article by the Australian champion, dealing with a question that every chess expert is asked ad nauseam. When a reporter asked it of the late Vera Menchik, she replied, “Oh, about one”. When another reporter asked it of the late Richard Réti, his dramatic sense got the better of him and he replied, “As a rule, not a single one”. Lajos Steiner gives a less cryptic reply’.

In his article, published on pages 265-266, Steiner wrote:

‘How far ahead to see? It is a question that everyone can answer for himself at the proper time, if he tries to approach positions with an open, critical mind. And that is the most important thing in a game of chess. It is better if we do not waste any more space at this juncture, and rather look at two positions.’

The diagrams given by Steiner:

White has a move which wins immediately

White mates in 90 moves

After outlining the solution to the second position, Steiner wrote:

‘An interesting piece of work, but the 90 moves of it are not much more difficult to see than the single move of the previous example.’

Steiner mentioned only that the problem was by Béla Bakay of Budapest, and we shall welcome further particulars. It is not one of the Bakay compositions in Ungarische Schachproblemanthologie by György Bakcsi (Budapest, 1983).

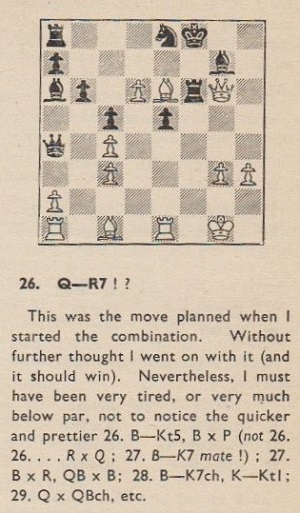

A future C.N. item will revert to the mate-in-90 problem, but the present item focuses on the first position. The game (Gerald Abrahams v František Zíta, London, 14 June 1947) was played on the first day of a two-round match between Great Britain and Czechoslovakia. From page 212 of the July 1947 BCM:

‘Abrahams succeeded in engineering one of his typical slashing attacks which apparently was quite sound, for on the 26th move ... he actually had an immediate win by a sensational queen’s sacrifice, first indicated by Professor Penrose.’

The game [a lengthy win for Black] was annotated by Abrahams on pages 14-18 of The Czechs in Britain by W. Ritson Morry (Birmingham, 1947). From page 15:

Abrahams gave the position (‘The game can be finished quickly by B-Kt5!’), mentioning neither the players nor the occasion, on pages 70-71 of The Chess Mind (London, 1951), although that information was added on page 72 of the Penguin edition (Harmondsworth, 1960).

(10035)

Some extracts from ‘Reflections after Reykjavik’ by Gerald Abrahams on pages 84-90 of Encounter, March 1973:

The use by many people of the term “Art” in application to chess is explained by the circumstances that chess is not an “exact Science”, as mathematics and astronomy are exact. (That chess is “not mathematical” I hold to be platitude.) Chess is comparable to the inexact empirical sciences (sometimes called “arts” in the sense of crafts), e.g. engineering, clinical medicine, some fields of chemistry, etc. Because chess is inexact – because to the vision of the player (and vision in his faculty) the board is not always translucent, is more usually opaque, concealing fields of chance – there is scope for judgment. There is also scope for style and there is scope for varieties of excellence. These differences enhance the impression of conflict between players. But as chess approaches asymptotically its scientific ideal, opponents (in the sense of “belligerents”) become unimportant. It is as if two engineers were tunnelling through an Alp. Each is opposed only by the thickness of the mountain and the thinness of his tools. So the chessplayer has no opposition other than the inherent difficulties of the subject matter and the limitations of his own mind. The opponent’s moves are relevant as possibilities which he must anticipate and control, and frequently fails to anticipate and control. The opponent embodies the task. But the opponent is not an ordinary adversary. In chess there is no adversary comparable to the bull or a boxer in a ring, to a batsman, a bowler, a centre-forward or a goal-keeper. Two persons are operating on the same board: each playing his private game against himself. As each one loses, he blames not the other, but himself. Not protagonist and antagonist here, but (a semantically unique case) two protagonists, each accidentally helping to constitute a test for the mental adequacy of the other.

So it is in my theory. As to practice, I only know one great player who behaved as if chess was completely “objective”. That was Akiva Rubinstein – a talmudist turned chessplayer. He was been called the “Spinoza of Chess”. But if you told this to the average super grandmaster (who has no metaphysics in his mind or music in his soul) he would ask “What tournaments did Spinoza win?” ...’

The famous Kt-R4 in that game may have seemed to Spassky to be a gamble; but there was profound and original thought involved in it. One is reminded of that fact that the immortal attack with which Fischer, playing Black, defeated Donald Byrne nearly 20 years ago, commenced with a sacrificial Kt-R5. If Fischer has a style, under his versatility, it seems to be characterized by clever knight play, and there was plenty in this match. In this respect he resembles Alekhine rather than Capablanca ...

In this game Fischer gave the friendly critic many reasons for admiration. First, he showed that chess strategy can be dynamic: not only knowing what to do when there is nothing to do; but a line of thought in which the tactics and the shaping of the game are integrated in purposeful play, involving a clear vision of long and subtle variations. This is great chess.’

There are, roughly, two ways of trying to win at chess. The tradition of Morphy, Steinitz, Capablanca and Rubinstein is to develop well and subtly, seizing very slight initiatives, converting them to advantages and the advantages into victory. Like “unheard melodies”, the Sturm und Drang are in the mind only. The other method, the method of Lasker and Alekhine, is to unbalance the game, bringing about skirmishes and hard fighting. There the great combinations are more frequently visible.’

Even below the level of ideal chess, good players play the board. A good player will not speak of “laying a trap” for an opponent. He makes a move to which he sees that his opponent cannot make the obvious reply on account of some quite hard-to-see possibility. But he will never make the second best move merely because it gives an opponent an easy chance of error. Good players always make the move that they think to be the best, and they assume that an opponent will not make mistakes.’

My own theory is that Jews, through evolutionary processes, have become good at languages. To be good at languages it is desirable to reach maturity early, and grasp the accidence and syntax and important vocabulary at an early age, so that while the mind is still young the student can express himself fluently and with mastery.

Among languages I include mathematics, music and chess. Different inter se, these systems are only grasped creatively by those who early grasp the technique. The particular Jewish control of chess is one instance of this process realized.

As for Fischer’s control of chess, let it simply be said that from now onwards the phrase Grand Master is meaningless.’

(10497)

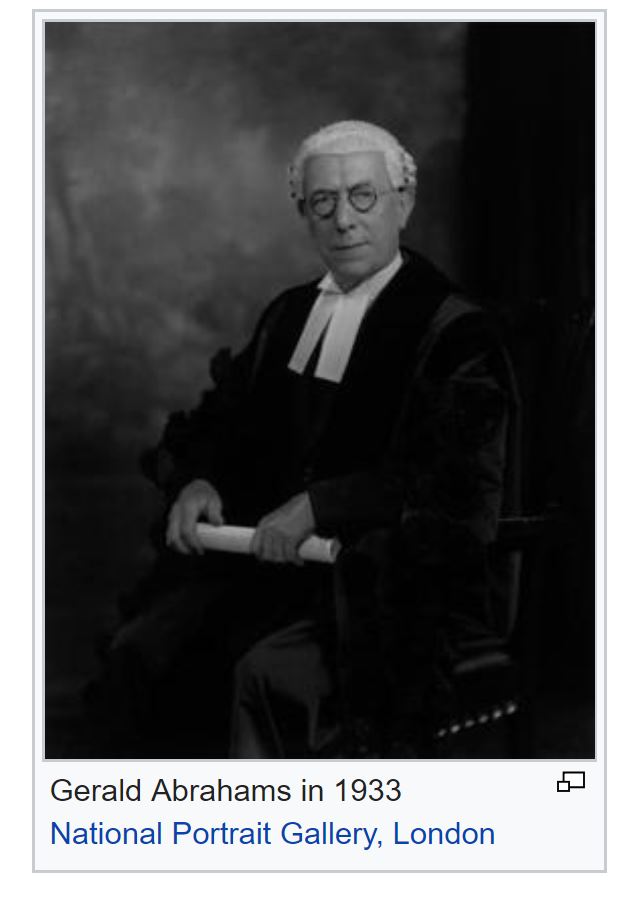

From the English-language Wikipedia entry for Gerald Abrahams:

See too the National Portrait Gallery’s Gerald Abrahams page, which has a number of similar shots, all dated 21 August 1933.

At that time, Abrahams was aged 26.

(10985)

The matter was raised again in C.N. 12138.

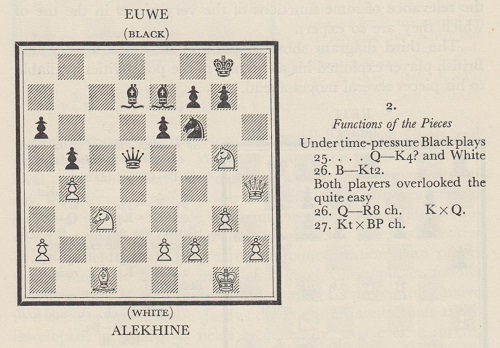

From page 13 of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951):

As already demonstrated, it was Alekhine, not Euwe, who was short of time.

Writers wishing to revel in world champions’ lapses may choose to ignore the issue of clock-pressure. See, for instance, pages 29-30 of The Inner Game of Chess by A. Soltis (New York, 1994) and pages 140-141 of the same author’s Chess Lists (Jefferson, 2002).

A sample comment from the latter book, after 27 a3:

‘Black continues to allow – and White continues to miss – the Qh8+ combination, the kind most 1800-rated players would find quickly.’

It may be pointed out, however, that Alekhine’s own annotations to the game, in his match book, had only one reference to the clock, and it was later in the game: he stated that at move 31 he ‘was very short of time’. Alekhine’s general view about time-shortage not being an excuse may be recalled from C.N.s 7973 and 10354.

(11137)

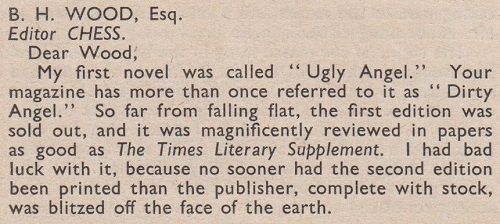

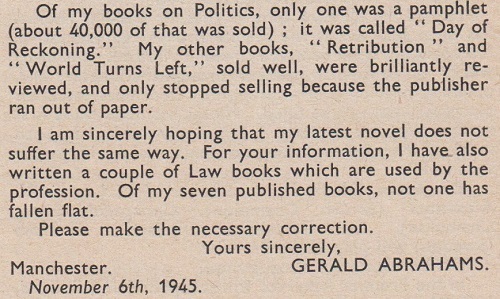

From page 29 of CHESS, November 1945:

Abrahams replied on page 52 of the December 1945 issue:

(11435)

An earlier brief reference to the novel, misnamed Dirty Angel instead of Ugly Angel, was on page 152 of the March 1940 CHESS.

George Kruger (Berlin) seeks further details regarding two matters mentioned in Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974):

On page 137 Abrahams described interviewing Lasker, Capablanca, Euwe, Flohr, Tartakower, Bogoljubow, Reshevsky and Fine for Tass during the 1936 Nottingham tournament. Can this material be found?

On page 203 Abrahams commented that Botvinnik ...

‘... was all but successfully challenged by a non-crypto-Jew, Bronstein (who later endeared himself to his masters by writing anti-Israel propaganda in the Russian press).’

Are such writings by Bronstein traceable?

(11920)

A good copy of this photograph would be welcome:

Evening Express (Liverpool), 6 January 1930, page 5

(12137)

On page 6 of the Liverpool Post & Mercury, 14 November 1932 Gerald Abrahams paid tribute to F.D. Yates:

From page 6 of the following day’s newspaper:

Yates’s loss to Sir George Thomas in Canterbury (1930) has been widely published. For a group photograph of participants in the tournament, see C.N. 4350.

(12139)

Some cutting-edge reportage about Gerald Abrahams on page 5 of the Liverpool Echo, 24 August 1950:

(12145)

From Chess and the House of Commons:

Gerald Abrahams discussed Andrew Bonar Law, William Watson Rutherford, John Simon and Richard Barnett on pages 37-38 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974):

From page 226 of CHESS, July 1946:

‘Gerald Abrahams writes: “I am 39 years of age and was a very good chess player between the ages of 10 and 14, since when I have deteriorated to master strength. I now claim to be the oldest child prodigy in the country.” Is Lancashire Champion and has held the championships of Oxfordshire and Liverpool and finished third in the British Championship. Took a First in Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Oxford and was subsequently called to the Bar; now practises on the Northern Circuit.

Is a witty and prolific writer on Political Philosophy and also of fiction. His parents were Russian. In the Sunday Chronicle tournament, in January, he finished equal fourth with König and Sir George Thomas.’

A paragraph on page 231 of CHESS, September 1952:

‘Gerald Abrahams, more than once Northern Counties Champion, author of The Chess Mind and Teach Yourself Chess, has been warned off British racecourses by Tattersalls’ in connection with a four-year-old debt of £75.’

Addition on 26 May 2025:

Below are two articles by Gerald Abrahams published when he was

in his late teens.

‘The Philosophy of Chess-Play

Original to the Chess Amateur by G. Abrahams, Liverpool“Of what use is chess?” The platitude of utility is the favourite weapon of the man in the street in his attack on the highbrow. “Wastrel”, cries the Titan by way of assault – what time the Olympian, girding on the armour of scorn and culture, hurls down the thunderbolt “Boeotian”, or in nineteenth-century parlance – Philistine.

Philistinism is not invariably to be condemned; it is often the outward form of sincere conservatism and acts as a useful check to a rather riotous and brow-beating modernism. Nevertheless, it is not always justified and chess, I think, is a martyr to it rather than a convict. The line of defence is clear. The Philistine has already conceded that apparently useless arts and sciences (such as Literature and Pure Mathematics) are of abundant and permanent value to the world. If then we can place chess – with any show of justice – in this category, our case is complete.

At the outset, I submit that chess is to be classed as a Science rather than as an Art; for in it the analytic predominates over the synthetic. But imagination transforms it into an art, as it transforms any science. Just as the philosopher, by virtue of the loftiness and universality of his conceptions, evolves quite a poetry from Mathematics or Physics, so can the master mind produce a thing of beauty from a game of Chess.

Without falling into the popular error of condemning Chess as essentially mathematical, I would say that it is a department of logic akin to mathematics but with equally pronounced affinities to the dialectic. The average game represents an argument – conducted on the elementary principles of attack and defence, question and answer – restricted by the material facts (or laws) of the game, and sublimated to a more refined degree of subtlety.

On the other hand, mathematical analogies can be multiplied to the glory of Caissa. It can be compared to a Calculus or Hyper-geometry based on certain assumptions of the human mind, but absolute as to its conclusions within those limits – a sort of experimental logic valuable in so far as the particular can exert any influence in fields of generalization. Indeed, it shares the characteristic with the whole of Science that while fundamentally relative it is intrinsically sound. True, Chess has never been applied to Philosophy; perhaps it is incapable of such extension; yet, as a training-ground for the mind it is invaluable and might even claim some recognition as a subject for specialization.

Psychologically, too, Chess is of value. The novice, here as elsewhere, can take in only one idea at a time, but gradually develops until he can comprehend the whole series of ideas – the whole game – at a glance. Subjectively, the study is of the first importance. Objectively, it is a great practical lesson in the evolution of thought. One might speculate and say: “Thus develop creatively the powers of analysis, as experiments, from elementary ideas and laws until the synthetic or imaginative stage is reached – unless the synthetic faculty has been developing analogously, or is superimposed from some other region of the mind.” The question is debatable and dangerously near to theological controversy.

But apart from practical science, Chess should appear to the philosopher as a monument to human intellect. If he be an Idealist, can he not see in the Chess piece the primal idea crystallized materially – and forming the centre of worlds of thought? And even the Realist should be moved to poetry at sight of the board and men – symbols as they are of Mind, its evolution from and conquest over Matter.’

Source: Chess Amateur, January 1926, page 123.

‘The Chess Problem as a Form of Art

G. Abrahams, Oxford‘Chess is a microcosm of human psychology. As I have endeavoured to show in a previous essay, it illustrates the evolution of thought from the particularizations of science to those illimitable generalizations which, for want of a better name, we term Art.

In chess, as in the mind, the Inductive principle reigns; the deductive being subordinate. In both the gamut ranges from tentative experiment to philosophical speculation – always hypothesis rather than logic. Thus, in its lower stages, chess is a dialectic form; at its height, it is a Creative Art.

The tendency in Art is from the imitative to the original, from the crude to the aesthetic, from the simple to the complex, from the diffuse to the compact – from lyric to drama.

Chess justifies itself as an art under its definition as the creative expression of the human mind. As art, it is dramatic, primarily because it postulates conflict (whether art as a whole should necessarily do so is debatable). It is dramatic too, because it affords scope for the compact, thematic, deep, subtle, and beautiful presentation of an idea. Chess thus crystallized becomes the Problem Art.

The essence of drama being the crystallized presentation of theme, then any product of mind which calls for the exercise of ingenuity, originality and imagination in its construction subject to the criteria of theme and beauty – be it limerick, mathematical puzzle, poem, or tour de force of any sort – is quite entitled to the description dramatic. Where any failing is indicated, it is usually a question of degree, not of kind. And in the matter of degree, I think the Chess Problem is entitled to high praise from the dramatic aspect.

The Problem, then, I would suggest, is not the Poetry of Chess contrasted with the Prose; it is rather the Drama as against the unwieldy Epic; and I think we are justified in applying to it, in terms of chess, dramatic canons.

The Problem has the fault of being almost hyper-dramatic. Like the modern play, it tends to the presentation of climax only; the dynamic element is at a minimum. I think that the complication, crisis, and catastrophe – or solution – might be at least indicated in the setting and in the variations. Greater length, too, would not be a disadvantage. This would make it truer to Chess, as the drama to life.

On the question of truth to Chess, I think there is a tendency, just as in the drama, to wander from Reality. Fairy Chess is too Romantic a species of drama to be acceptable; it becomes mere speculation in a Mathematical system which is not Chess as played, and in which the introduction of the name and limitations of Chess is an irrelevancy. Fairy Chess and the geometric theme problems are forms of Science, not of Art – and if there is art in them, it is not based on Chess. Meanwhile if Chess as a game is justified – and are not all the transitory forms of art and life more or less justified – the laws of the game to the Problem should be as the laws of life to Drama, for art is the imitation of an accepted Reality.

The Problem offers plenty of scope for Beauty and Intensity of theme, but neither should exclude the other; there is also plenty of room for improvements in size. Finally there is a demand for naturalness in problems which would not be a bad thing. Here again, interest depends on the truth of the production.

For the rest, the problem is as far from being worked out as Chess is; and as the latter develops as a branch of thought, the Problem may well take its place as a work of art, and, as a thing of Beauty, become a joy for ever.’

Source: Chess Amateur, April 1926, pages 219-220.

On page 220, the Chess Amateur noted that the third word from the end of the first article should have read ‘conquest’, and not ‘consequently’.

‘... Emanuel Lasker, whose brain was second to none, mastered every move of bridge without being a successful performer. I never saw him play bridge, but hearsay tells of his rigidity. I saw Capablanca play bridge. He played very well indeed, but woodenly. He whose chess was so fluid. These two great chessplayers failed to develop a “flair” for cards.’

This is the late Gerald Abrahams in his essay Mental Processes in Chess and Bridge on pages 120-132 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974). The account contradicts several other recorded views of Lasker and Capablanca’s card skills, but Abrahams was an author (and an authority) on both chess and bridge.

(38)

The view of G. Abrahams on Emanuel Lasker’s ability at bridge, quoted in C.N. 38, would seem to be confirmed by Milan Vidmar, writing on page 2 of his excellent memoirs Goldene Schachzeiten (Berlin, 1961):

‘Ich spielte einige Abende in Nottingham mit Lasker Bridge. Er war in diesem Spiel durchaus nicht der große Meister, den man in ihm hätte erwarten können. Er war auch durchaus kein sehr angenehmer Spielteilnehmer. Selbstverständlich weiß ich sehr gut, daß es eine große Kunst ist, in irgendeinem Spiel mit Anstand zu verlieren.’

(274)

From George Stern (Woden, Australia):

‘C.N. 38 refers to the late Gerald Abrahams as “an authority on both chess and bridge”. I cannot judge the quality of his expertise in bridge, but I am less than an ardent admirer of his in the field of chess. I have before me the 1975-6 Year Book of the Encyclopaedia Judaica (Keter Publishing House Jerusalem Ltd.) On page 253, under the heading of “Chess” , Gerald Abrahams writes:

“Bobby Fischer lost the World Championship in 1975 when he refused to play the challenger Vassily Karpov. ... The British chess championship held in August 1974 ended in a tie between seven players, of whom three, William Hartstone, ... Jonathan Mestel, ... and Michael Stean, are Jewish. ... The play-off was won by Botterell.

... Israel chess has been further strengthened by the arrival from USSR of Grand Master Leonid Shumkovitch ...”

The entry ends with a blurb for his book, Not Only Chess. In the Decennial Book 1973-82 of the same work (issued by the same publisher), on page 205, under the byline this time of Gerald Abrahams/Editor, the article on chess refers to “Vassily Karpov” , “William Hartstone” , “Jonathan Mester” and “Leonid Shumkovitch”; and there is another blurb for Not Only Chess. Incidentally, after reading the earlier volume, I wrote to the publisher pointing out the errors; but the only impact this had on what appeared in the later volume was that it induced the publisher to add a new error – “Jonathan Mester”.’

We note a further mistake added in the Decennial Book: ‘Three of the seven participants in the British Chess Championship held in August 1974 were Jewish ...’, whereas the tournament had 32 players. The 1982 book gives no indication that Abrahams had died in 1980.’

(1739)

Another chess expert who wrote on bridge was Gerald Abrahams, with Brains in Bridge (1962). He also brought out books on such subjects as law and political thought, as well as publishing three volumes of fiction. A list of his output is given opposite the title page of his 1974 book Not Only Chess.

(2591)

In his Preface on pages xi-xii of Brains in Bridge Gerald Abrahams wrote:

‘Every chessplayer, it has been well said, has at least one other major vice. Some evidence of this is afforded by the fact that the list of acknowledged British bridge masters includes some chess players of at least County strength.

I recall that that brilliant chessplayer and excellent bridge player, the late Victor Wahtuch [sic – Wahltuch], expressed the view that bridge could involve some intellectual efforts comparable to those of hard chess. I expect that that utterance was biased by the fact that chess came very easily to him, who mastered it very early in life, and his bridge was a late acquisition. What is more important is the consideration that the intellectual activities involved in the respective games can be usefully compared and contrasted. If I am right in this, then it may well be that some player, chess conscious and bridge conscious, will from these pages acquire an extra insight into bridge. Who knows? The book may even improve his chess.’

Abrahams then added a footnote:

‘I do not, in this book, seek specific analogies in bridge to chess. There are certainly some comparisons to be made. “Smothered mate” and “Smother play”, for example; and “opposition” is suggested by many bridge endings. But what I am concerned with is the analogy between the mental process of persons engaged in manoeuvring, respectively with chess pieces, and the pieces of pasteboard that are used on the bridge board. One very important difference consists in the fact that, whereas most chess positions offer great range for thought, a very large percentage of bridge hands offer very little scope. But the two games have this in common: that it is easy to miss the demand for thought that is latent in the apparently simple position. On the other hand, a common factor is the large element of common sense which is basic to both games.’

(3280)

Addition on 20 June 2025:

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) quotes the following from Terence Reese’s Foreword to Brains in Bridge (Teach Yourself edition, Constable, 1977, page v):

‘I have played a fair amount of bridge with Gerald, and can report that his game is ... imaginative. (I can say this without any fear of retaliation because I have never exposed to his gaze the diligent wood-pushing that for me passes as chess.) But what if he is not a virtuoso of bridge as he is of chess? The best theatrical critics are not necessarily the best actors. Abrahams is witty, but not facetious, cultivated, but not dull, discursive, but not disconnected.’

From Chess and the Wallace Murder Case:

Gerald Abrahams, who was a chessplayer, barrister and Liverpudlian, made a number of comments on the case. The following two passages appeared respectively on pages 148 and 149 of Hussey’s book:

‘It is perhaps significant that one barrister-commentator, Gerald Abrahams, says of Oliver’s defence of Wallace that a “defence that could, and should, have been declaimed on a high note was soft-pedalled”.’

‘In According to the Evidence, barrister Gerald Abrahams of Liverpool puts the Wallace prosecution succinctly: “To any objective observer, the hypothesis which is the prosecution’s case is something so intrinsically difficult of acceptance that the defence does not seem to matter. Putting the prosecution at its highest, it leaves doubt.”’

On page 171 Hussey wrote: ‘Barrister Abrahams states: “The judge ... summed up strongly for acquittal.”’ He did indeed ...

... Gerald Abrahams’ treatment of the facts of the case was hardly error-free. For example, on page 63 of According to the Evidence he gave the wrong year for the crime: ‘The murder of Mrs Wallace took place late in 1930 ...’ On pages 64-65, in a paragraph discussing the evening of the murder, the timings stated by Abrahams were all an hour out (six times).

We note too that Abrahams also discussed the case on pages 151-154 of his book The Legal Mind (London, 1954). After describing the basic facts, he wrote of Wallace:

‘And there were other equally powerful arguments, such as that the man was a chessplayer (to the author’s knowledge the worst that ever moved a pawn) and consequently capable of concocting great schemes of devilry and deception. The jury was of a type that could not recognize a non sequitur.’

Abrahams provided the following analysis:

‘Journalists have agitated their readers for many years with the question: was Wallace guilty?

There are three approaches to this question:

(1) Legally, it is academic. There was no evidence against him.

(2) Personally. His acquaintances (excluding those who revel in the troubles of their “friends”) seem convinced of his innocence. The author takes the view that to vest Wallace with guilt in the circumstances is to credit him with a mental power, a skill, an agility, a cold-blooded nerveless efficiency, of which he seemed utterly incapable.

(3) Scientifically, it is a much easier hypothesis to assume another person as murderer, whose task would have been easier, mental effort less. By the principle of simple explanations Wallace was innocent.

For the rest, the Wallace case illustrates one danger of the otherwise excellent English Jury system, viz. that in a complex case the jury does not see through complex facts and complex characters, and is apt to take too seriously the fact that the charge has been brought.’

Regarding Capablanca v Fine, AVRO 1938, as covered by Abrahams in Teach Yourself Chess, see our feature article.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.