Edward Winter

See C.N. 7356 below.

Our main feature articles on the eight participants at the AVRO, 1938 tournament in the Netherlands:

Alexander Alekhine

Mikhail Botvinnik

José Raúl Capablanca

Max Euwe

Reuben Fine

Salo Flohr

Paul Keres

Samuel Reshevsky.

AVRO is the acronym of Algemeene Vereeniging Radio Omroep.

As mentioned on page 260 of Chess Explorations, C.N. 593 quoted Fine’s observation in Lessons from My Games (page 152) concerning AVRO, 1938:

‘It is curious that not a single player dared to try a Sicilian in the whole tournament.’

Our translation of an extract from an article by Alekhine on Munich, 1941, published on pages 187-189 of his book ¡Legado! (Madrid, 1946), having earlier appeared in Ajedrez Español, January and February 1942 (pages 6-7 and 32-33).

‘This tournament can be compared with advantage to Semmering-Baden 1937 and AVRO 1938, in which the aims were chiefly connected with commercial propaganda; the masters had to play in an unsatisfactory atmosphere quite out of keeping with the elevated spirit which the art of chess requires. There were nonetheless excellent individual results, but the sporting performances were falsified by the inevitable physical fatigue of the players, who were taken on a danse macabre, from one Dutch town or city to another (in the case of AVRO) like exhibition objects or low-grade fighters.’

C.N. 2170 (see page 241 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) gave our suggestion for the first game in which it is known how much time was consumed on the individual moves: Reshevsky v Alekhine, AVRO, 1938 (CHESS, 14 December 1938, pages 147-149).

From World Championship Disorder:

In mid-December 1937 Alekhine decisively regained the world title from Euwe. The AVRO tournament went ahead in late 1938, but without the status of a candidates’ event. As was reported on page 509 of the November 1938 BCM:

‘… since there have been all sorts of rumours as to a world championship match resulting from this tourney we have been permitted by Dr Alekhine to publish the clause in his contract with AVRO dealing with this question. It runs as follows: “Dr Alekhine declares himself ready to play a match for the world championship against the first prize winner of the tournament upon conditions and at a time to be arranged later. However, Dr Alekhine reserves the right to play first against other chess masters for the title.” So the reader will observe that this clause in no way affects Dr Alekhine’s projected match v Flohr, which is due to take place next year.’

There has probably never been another period in chess history with so many ‘projected matches’ that failed to materialize. The AVRO tournament itself clarified nothing, except that the two ‘Stockholm finalists’, Flohr and Capablanca, finished bottom, in eighth and seventh places respectively.

Alekhine v Fine, AVRO, 1938, with Flohr behind the world champion

Then there was Emanuel Lasker, who was upset at not being invited to participate in the AVRO tournament. In an interview with Paul H. Little on pages 14-15 of the January 1938 Chess Review, ‘the veteran commented that his own record in tournament play against the leading world masters (particularly against the three other world champions), since his loss of the title in 1921 to Capablanca was enough to qualify him as a candidate who ought not to be overlooked. Dr Lasker feels that Dr Rueb is a foe of the creative master.’

Because Nottingham, 1936 was Emanuel Lasker’s last tournament it is sometimes assumed that thereafter he retired from top-level play. In a letter published on page 194 of the May 1969 Chess Life Joseph Platz commented on Lasker’s absence from AVRO, 1938:

‘It is useless to speculate how the man who was among the top players of the world for 50 years would have fared at the AVRO tournament. Had he been invited, he would have played. Lasker and I were good personal friends and he expressed bitter disappointment that he was not invited.’

(2430)

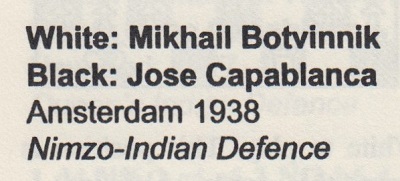

Some comments by Botvinnik, from page 94 of the Pergamon book Half a Century of Chess (Oxford, 1984) regarding his brilliant 30 Ba3 v Capablanca at AVRO, 1938:

‘The beginning of a 12-move combination, including the following winning manoeuvre. I must admit that I could not calculate it right to the end and operated in two stages. First I evaluated the position after six moves and convinced myself that I had a draw by perpetual check. Then after the first six moves I calculated the rest to the end. A chessplayer’s resources, particularly at the end of a game, are limited.’ (Interesting, since annotators have stated that Botvinnik had foreseen everything.)’

(863)

A paragraph from our article on World Champion Combinations by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller (New York, 1998):

Keene and Schiller report that Euwe dethroned Alekhine in 1937; everybody else believes that Euwe won the title in 1935 and lost it in 1937. Page 119 erroneously declares that Botvinnik won the 1954 world championship match against Smyslov. The first page of the Botvinnik chapter says: ‘Beating Capablanca was an achievement that every World Champion in the first half of the 20th century achieved, and Botvinnik was the last of a long line to do so …’. (Let’s pause here to admire the polished prose style: ‘an achievement … achieved’.) In reality, of course, the ‘long line’ consisted of just four champions, and the last of those victories was by Euwe, not Botvinnik. Regarding the famous game Botvinnik-Capablanca, AVRO, 1938, page 101 affirms after 34 e7, ‘Of course Botvinnik had to see that there was no perpetual check when he played 30 Ba3’. That is flatly disproved by Botvinnik’s own annotations on pages 92-94 of Half a Century of Chess; after 30 Ba3 he wrote: ‘I must admit that I could not calculate it right to the end and operated in two stages. First I evaluated the position after six moves and convinced myself that I had a draw by perpetual check. Then after the first six moves I calculated the rest to the end.’

‘Botvinnik-Capablanca, Amsterdam 1938’ is the game heading in Jewish Chess Masters on Stamps by F. Berkovich (Jefferson, 2000), page 108, i.e. in the section written by N. Divinsky. It is an elementary mistake, commonly seen. Botvinnik’s famous brilliancy was played (on 22 November 1938) in Rotterdam, as is recorded by many contemporary sources (e.g. page 106 of Euwe’s book on the tournament).

The bibliography of the Berkovich book (page 132) contains some improbable references, such as items purportedly written by L. Shamkovich and D. Spanier in 1935 and 1934 respectively.

(2976)

Quiz question: how many games did Capablanca lose in Amsterdam at the AVRO tournament of 1938?

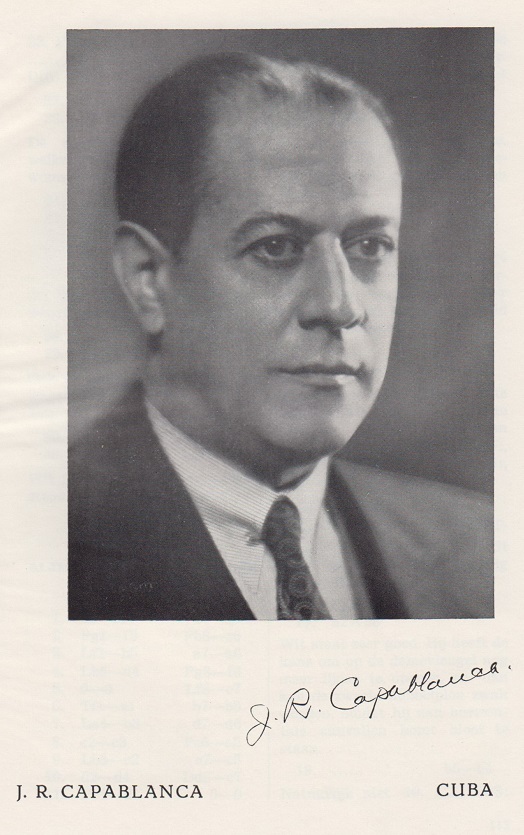

This portrait comes from opposite page 112 of Analysen van A.V.R.O.’s wereld-schaak-tournooi by M. Euwe (Amsterdam, 1938). It is one of several tournament books which show that the Cuban’s losses were as follows:

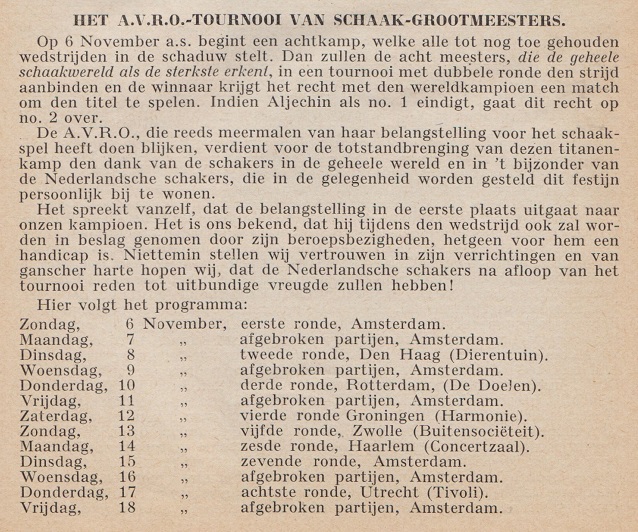

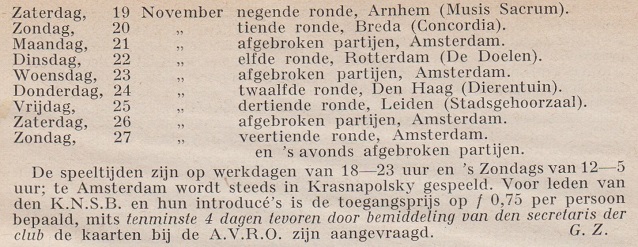

A list of dates and venues is on pages 299-300 of the October 1938 Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

The answer to the quiz question is thus that Capablanca lost one game in Amsterdam, against Euwe, but it is often misstated that the other three defeats also occurred in the Dutch capital. For instance:

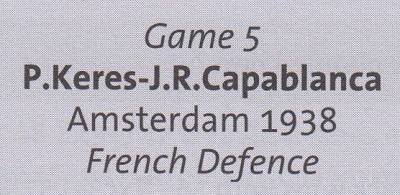

Chess Strategy for the Tournament Player by L. Alburt and S. Palatnik (New York, 2000), page 190

Keres move by move by Z. Franco (London, 2017), page 94

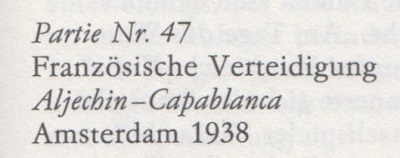

Das Schachgenie Aljechin by I. and W. Linder (Berlin, 1992), page 251

Aleksander Alechin by K. Pytel (Warsaw, undated), page 150

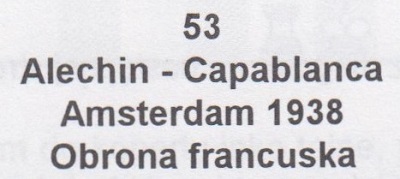

The Sunday Times Book of Chess by R. Keene (Aylesbeare, 2005), page 30

Mikhail Botvinnik by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 2014), page 111.

(10413)

From page 272 of Chess Explorations:

On page 242 of the June 1979 CHESS we published Emanuel Lasker v Powell, simultaneous exhibition, Liverpool, 1895, a game which saw play similar to Botvinnik’s against Capablanca [AVRO, 1938]. Lasker too offered the sacrifice Bb2-a3 with the aim of diverting the enemy queen, which was blocking a white passed pawn at e6.

An extract from our translation of an interview with Capablanca published in the Buenos Aires magazine El Gráfico, 1939 and reprinted on pages 103-107 of Homenaje a José Raúl Capablanca (Havana, 1943):

‘[Interviewer’s question: But master: if you took Dr Lasker’s world championship title when the great Berlin master was in the plenitude of his powers, and if modern players, in your opinion, are clearly inferior to Lasker, how do you explain the fact that some of them have finished above you in many international tournaments? How do you explain your seventh place at the AVRO tournament in Holland?]

In the AVRO tournament I played under physical conditions that were absolutely abnormal. Although I am not up to date with chess literature, I played the openings well in all my games for the simple reason that I have judgment. But after the first three hours of play, I felt my head was splitting. It was impossible for me to think and coordinate ideas. Against Fine I had two won games; against Alekhine I should have won one game; and another one against Keres, thanks to an advantageous position which I built up conscientiously. But at the moment of transforming my advantage into victory, I found that my brain was not functioning and I then continued playing not with my head but with my hands. Despite the bitter cold of Holland in November, I immersed my congested head in icy water to try to clear it, although without any result ... I thus participated in the AVRO tournament playing like an automaton after the third hour, and it is therefore understandable how frequently I failed to win.’

Olga Capablanca’s reminiscences about AVRO, 1938 are given in The Genius and the Princess. Russian version: Гений и княгиня.

A contribution from Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

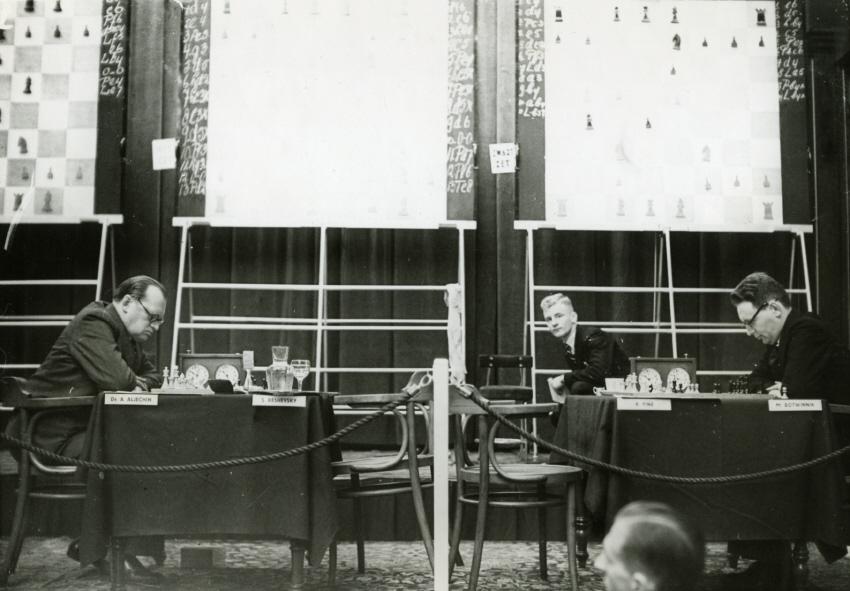

Alexander Alekhine and Mikhail Botvinnik, AVRO, Amsterdam, 6 November 1938

(4791)

This photograph was taken in Amsterdam on 6 November 1938 during the first round of the AVRO tournament, the players being, from left to right, Euwe, Keres, Flohr, Capablanca, Alekhine, Reshevsky, Fine and Botvinnik. It was one of many shots from De Telegraaf reproduced on pages 139-142 of CHESS, 14 December 1938.

(6640)

(7021)

We are grateful to a number of readers who attempted to identify the figures in the airport photograph. The key is provided by a cutting in our archives from the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf in November 1938 (exact date unavailable):

(7060)

Addition on 17 June 2025:

Wijnand Engelkes (Zeist, the Netherlands) gives the date of the newspaper: 12 November 1938.

CHESS (14 December 1938 issue, page 142) gave this picture in its coverage of AVRO, 1938:

(7136)

From Chess Review, January 1939, page 7:

(7191)

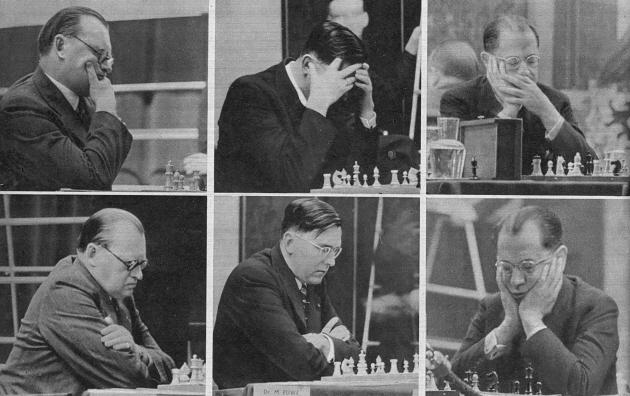

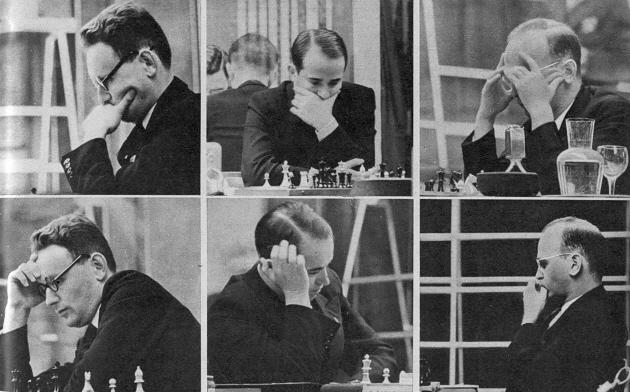

Pages 57-59 of Picture Post, 26 November 1938 had a richly illustrated article on that year’s AVRO tournament. Below are all the photographs on pages 58-59. The first of them is 52 cm long in the magazine and has been split here into two:

M. Botvinnik, S. Reshevsky, R. Fine and S. Landau (‘for Capablanca’)

M. Euwe, A. Alekhine, S. Flohr and P. Keres

A. Alekhine, M. Euwe and J.R. Capablanca

M. Botvinnik, S. Flohr and S. Reshevsky.

No individual photographs of R. Fine and P. Keres were given.

(7356)

The above photograph of Paul Keres was published opposite page 16 of Analysen van A.V.R.O.’s wereld-schaak-tournooi by M. Euwe (Amsterdam, 1938).

From page 82 of CHESS, 14 November 1938 comes a comment written by Paul Keres to B.H. Wood shortly before the tournament began:

‘It will be an achievement not to be last.’

(7400)

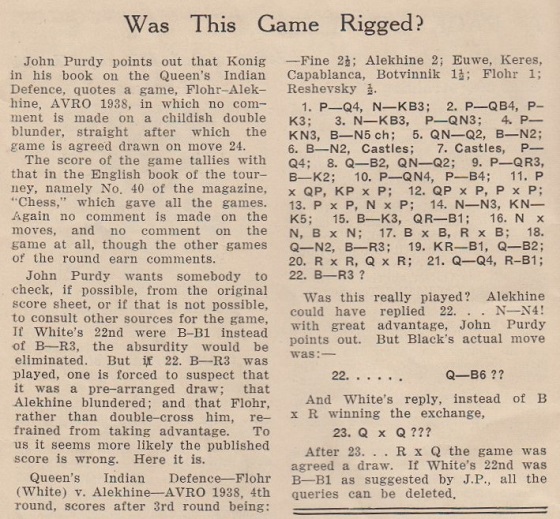

From page 30 of the January 1957 Chess World:

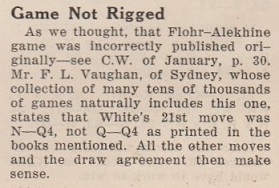

The question in the headline was answered on page 60 of the March 1957 issue:

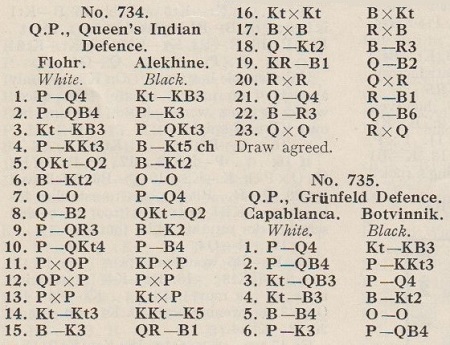

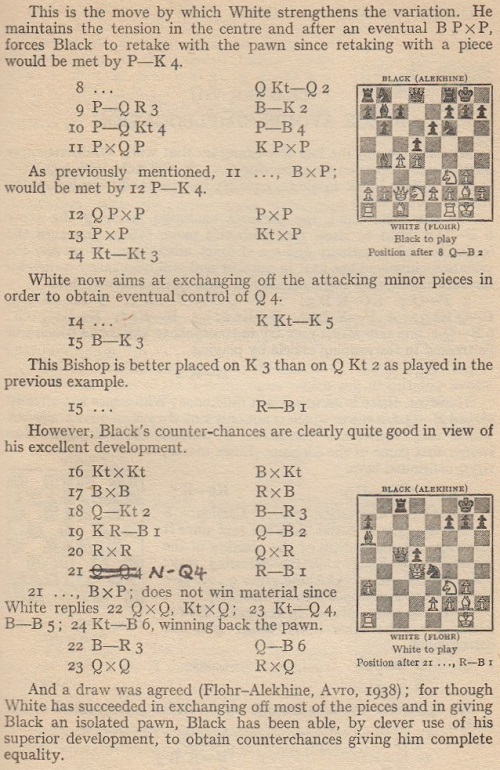

The full score of Flohr v Alekhine, AVRO, 12 November 1938: 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 b6 4 g3 Bb4+ 5 Nbd2 Bb7 6 Bg2 O-O 7 O-O d5 8 Qc2 Nbd7 9 a3 Be7 10 b4 c5 11 cxd5 exd5 12 dxc5 bxc5 13 bxc5 Nxc5 14 Nb3 Nfe4 15 Be3 Rc8 16 Nxc5 Bxc5 17 Bxc5 Rxc5 18 Qb2 Ba6 19 Rfc1 Qc7 20 Rxc5 Qxc5

21 Nd4 Rc8 22 Bh3 Qc3 23 Qxc3 Rxc3 Drawn.

Apart from the two mentioned by Purdy, the sources that we have consulted state that White’s 21st move was Nd4, and not Qd4, with one notable exception: page 632 of the Skinner/Verhoeven volume on Alekhine.

The publications cited by Purdy are shown below, beginning with page 131 of the 14 December 1938 issue of CHESS (the sole source indicated by the Skinner/Verhoeven book):

In the relevant part (pages 46-47) of König’s book The Queen’s Indian Defence (London, 1947) our copy has a handwritten correction at move 21:

(9797)

On page 10 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Reuben Fine wrote regarding Alekhine:

‘When World War II ended, in 1945, all the leading masters of that day, incensed by his behavior, objected to his participation in international tournaments. The Soviets broke the boycott by having Botvinnik challenge Alekhine to a match for the title in 1946. Actually this was illegal, since Keres and I had prior claims. But Keres, born in Estonia, was a Soviet citizen, while I was no longer so interested.’

From pages 224 of the ‘revised and expanded edition’ of The World’s Great Chess Games by Fine (New York, 1976):

‘Legally there were various possibilities. Euwe might have reclaimed the title, as the last official champion before Alekhine. Or Keres and Fine could have been declared co-champions on the basis of their joint victory in the AVRO tournament. Or Euwe, Fine and Reshevsky might have played a three-cornered tournament to decide the championship. Or the free world might have chosen a champion, and the communist world been left to choose its own; then the two could have met for the world championship.’

On the next page Fine wrote with respect to AVRO, 1938:

‘As indicated before, on the basis of this victory and in light of the circumstances of international chess in the war period, Keres and I should have been declared co-champions for the period 1946-48, between the death of Alekhine and the 1948 tournament.’

Finally, a comment by Fine on page 151 of Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘Keres and I tied for first in the AVRO tournament; he was declared winner by the tie-breaking Sonnenborn-Berger [sic] system. Alekhine dodged a match in his usual skillful manner. Then the war intervened and all official chess activity stopped.’

There is a frequent lack of rigour in claims that Alekhine ‘dodged’ opponents, and it is unimpressive to find C.J.S. Purdy writing the following in a review of Lessons from My Games on pages 146-147 of Chess World, September-October 1967:

‘Reuben Fine became one of the world’s greatest players. At the time when his claims to play a match for the world title were unanswerable, he did not get to play a match because Alekhine, once he had regained his title from Euwe, did everything possible to evade a match.’

As regards possible challenges to Alekhine after AVRO, 1938, an observation on page 215 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004) is noteworthy:

‘Fine seems not to have made any effort at all ...’

Related feature articles:

(10288)

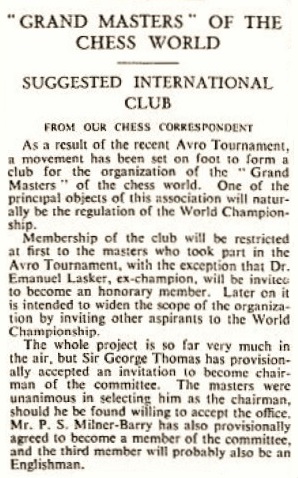

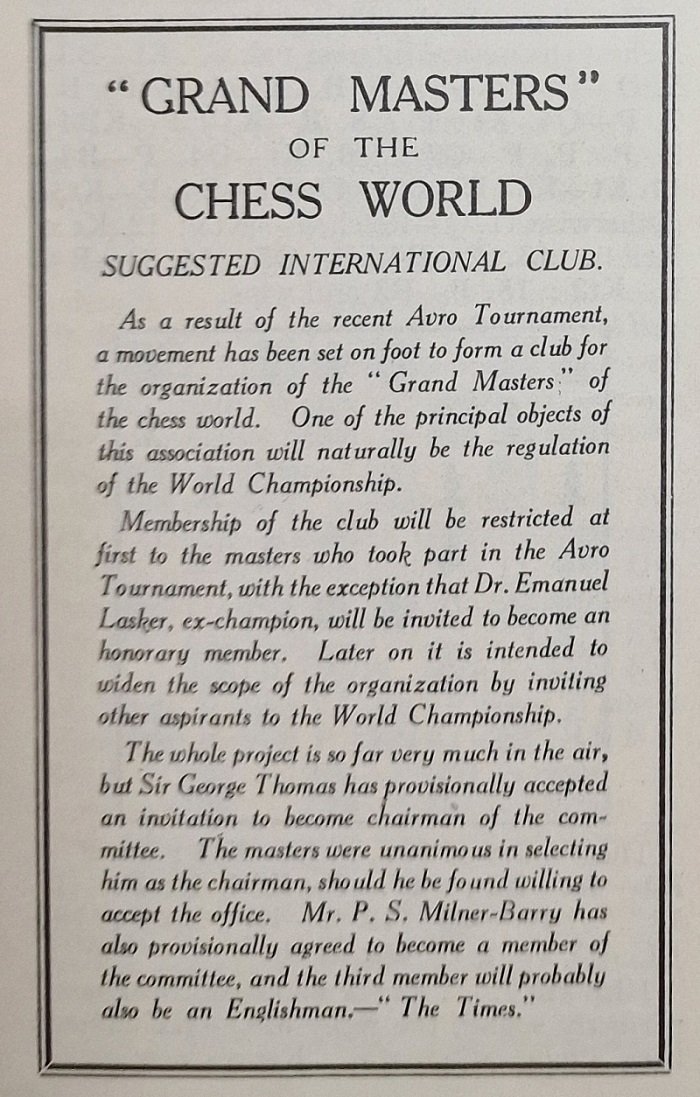

A project announced on page 8 of the (London) Times, 4 January 1939:

The report was reproduced on page 167 of the January 1939 CHESS, as mentioned in C.N. 1590:

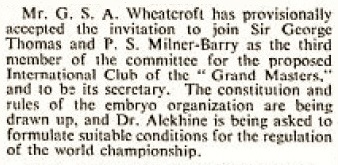

Page 8 of the 16 January 1939 edition of the Times had a brief follow-up note about the Anglocentric initiative (on which further information is sought):

(10695)

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) writes:

‘In a letter to Ilya Maizelis (New York, 7 July 1939), Emanuel Lasker wrote:“Der Vereinigung der Schachmeister, deren Mitglieder Botwinnik, Alekhin, Capablanca, Euwe, Flohr, Fine, Reszhewski, Keres sind, bin ich nun angeschlossen und hoffe, dass sie etwas zur Förderung des Meisterschachs beitragen wird.”

Are any details known about this attempt to form a masters’ association, perhaps in conjunction with the AVRO, 1938 tournament?’

(11892)

See Chess Grandmasters.

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) informs us that he has acquired from the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision the right to post on his Patreon webpage [broken link] a brief audio file of Capablanca speaking in English during the AVRO tournament, on the occasion of his 50th birthday (19 November 1938).

(11337)

The opening of our article Harry Golombek’s Book on Capablanca:

Capablanca won a tournament in New York, 1914 with a clean score. There were 14 draws in his world title match against Lasker and 21 draws in his match with Alekhine. The AVRO tournament was in 1937. These and countless other obvious mistakes have appeared in various editions of Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by Harry Golombek (originally published by G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., London, in 1947).

Another feature article is Capablanca v Fine: A Missed Win.

Position after ...hxg5

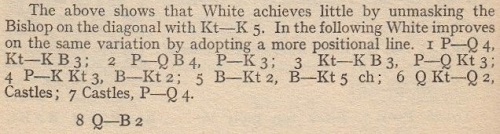

Critical Moments in Chess discusses this position from the AVRO game Fine v Keres:

White to move

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.