Edward Winter

‘One of the most remarkable Grünfelds ever played’ is how Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) described the game below when submitting it to us some 23 years ago (see page 141 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 e3 Bg7 5 Nf3 O-O 6 cxd5 Nxd5 7 Be2 Nxc3 8 bxc3 c5 9 O-O cxd4 10 cxd4 Nc6 11 Bb2 Bg4 12 Rc1 Rc8 13 Ba3 Qa5 14 Qb3 Rfe8 15 Rc5 Qb6 16 Rb5 Qd8

17 Ng5 Bxe2 18 Nxf7 Na5 and White mates in three.

Why remarkable? Because the game was played not just before Grünfeld’s career but even before Morphy’s. According to the Chicago Tribune of 13 July 1879, which took the score from the Glasgow Herald, the game was played between Cochrane and Moheschunder in May 1855. It was also annotated by Steinitz in The Field of 6 June 1874, page 565.

(Kingpin, 1990)

Ernst Grünfeld

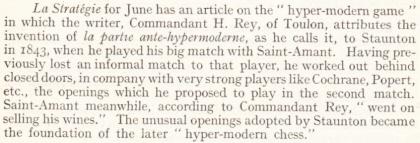

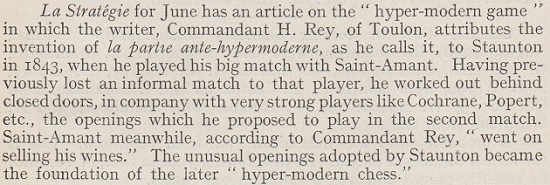

A question discussed in C.N. 1157 is when Howard Staunton’s supposed contribution to hypermodernism was first noted. We offered this passage from page 360 of the August 1926 BCM:

An observation by W. Wayte on pages 476-477 of the December 1889 BCM:

‘Staunton, perhaps, did not begin the “struggle for position” quite soon enough in his openings, relying rather on combination in the middle game; yet with his eminent grasp of the board as a whole he is at least the forerunner of the modern school.’

(2461)

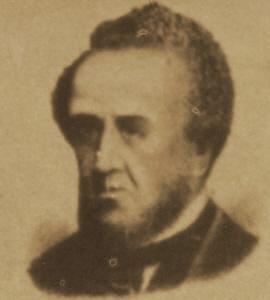

Howard Staunton

C.N. 3764 recalled that in the chapter ‘Ahead of Their Time’ in The Chess Companion (New York, 1968) Irving Chernev declared himself intrigued by Elijah Williams’ performance at London, 1851. From page 184:

‘Was his prolonged thinking part of a plan to infuriate his opponents? Or was it because he was slowly evolving a new system of play?

The terms “Double Pawn Complex” and “Zugzwang” could have had no meaning for Williams, but here, in two games [against Löwenthal and Staunton], we have this Nimzowitsch of a hundred years ago demonstrating these concepts.’

Chernev’s item originally appeared as an article on page 340 of the November 1955 Chess Review. We should like to know whether other writers have attempted to back up his theory; nothing particularly helpful has yet been found in Williams’ book Horæ Divanianæ (London, 1852) or in other sources.

Joseph Henry Blackburne

Even J.H. Blackburne has been suggested as a possible precursor of hypermodern play. From page 207 of The Game of Chess by Harry Golombek (various editions):

‘His games, though so strongly influenced by Morphy, also curiously foreshadow the most modern developments. For example, as early [as] in 1883 at the great international tournament in London he was playing as Black the first three moves of Nimzowitsch’s Defence to the Queen’s Pawn, three years before the birth of Nimzowitsch; whilst his English opening at Ostend, 1907 was remarkably similar for some 12 moves to the system evolved many years later by Réti.’

That claim was mentioned in C.N. 283, and in C.N. 411 W.H. Cozens (Ilminster, England) gave his view on whether Blackburne’s games showed evidence of a system:

‘No, not at all. He was the most faithful exponent of the open game right to the last. Even in his last tournament (St Petersburg, 1914) he played 1 e4 most of the time. We tend to forget his sense of humour. When he sat down opposite Nimzowitsch one can almost see the twinkle in his eye as he opened 1 e3 d6 2 f4, etc. (and won). If anyone tried to be funny with him he played along. Gunsberg v Blackburne went 1 e3 g6, followed by ...Bg7, ...d6, ...e6, ...Ne7, ...O-O. Late in life, like other aged masters, he did not trust his own opening erudition against the youngsters (e.g. he met Marshall’s Q-Pawn with ...Nf6, ...c6, ...d6, ...Qc7). But to see a hypermodern system in all this is reading into it more than is there.’

On page 260 of Chess Explorations we added that the Blackburne games from Ostend, 1907 which Golombek appeared to have in mind were against E. Znosko-Borovsky, W. John and E. Cohn.

Examples of openings played before their supposed ‘invention’ are always of interest. On pages 18-21 of R.P. Michell, A Master of British Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1947) there is a game against Siegheim played in London in 1903 in which Michell (as Black) opened 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 b6 4 Nc3 Bb4.

C.N. 1218 pointed out that page 238 of Tartakower’s My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 (London, 1953) called a game beginning 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 Bb4+ ‘Neo-Indian Defence, Buckle-Bogoljubow Variation’. Tartakower’s claim that 3...Bb4+ ‘is already to be found in some of the games of Buckle’ remains to be proven; the closest example we have found so far is 1 d4 e6 2 c4 Bb4+ 3 Nc3 Bxc3+ (Löwenthal v Buckle, fourth match-game, London, 1851).

(2029)

John Donaldson (Seattle, WA, USA) sends an English translation by R. Tekel and M. Shibut of an interesting article by Reti ‘Do “New Ideas” Stand Up in Practice?’, published on pages 8-10 of the Virginia Chess Newsletter of September/October 1993.

A sidelight is Réti’s nomination for White’s best first move: 1 c4. His reasoning begins: ‘One would expect Black's strongest point in the centre to be d5 since, unlike e5, it has natural protection by the queen. Therefore, the ideal initial move is 1 c4, immediately taking aim at d5.’

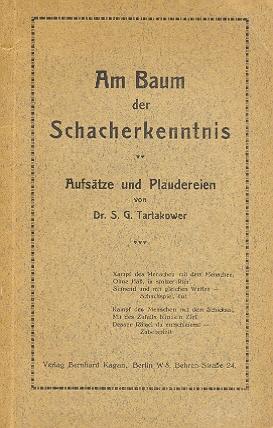

Tartakower (see page 15 of his book referred to in C.N. 2029) called 1 c4 ‘the strongest initial move in the world’.

(2030)

Alexander Flamberg

C.N. 3692 referred to Flamberg v Levitzky, St Petersburg, 1914, noting that on pages 43-44 of Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933) Fred Reinfeld and Irving Chernev wrote by way of introduction:

‘The Polish master Alexander Flamberg was a highly gifted player with profound and original ideas. Chronic ill-health prevented him from ever asserting his full powers.

Concerning one of his notable games – one of the most significant in the history of chess – his countryman Przepiórka has commented as follows: “When one examines the opening moves and the subsequent course of the game, it is almost incredible that it was played in 1914 ... The double fianchetto of the bishops, the operations on both wings, and later on the manoeuvers with the black knights and the posting of the queens on the long diagonal – all these ideas are, as we know, considered the very latest achievements of the Hypermoderns.”’

The comments by Przepiórka appeared on page 34 of the February 1926 Wiener Schachzeitung. He used the term ‘A Prophetic Game’ to describe Flamberg’s victory:

Alexander Flamberg – Stepan Mikhailovich Levitzky

All-Russian Masters’ Tournament, St Petersburg, 16 January 1914

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 g3 Bb7 4 Bg2 e6 5 O-O Be7 6 b3 O-O 7 Bb2 d6 8 c4 Nbd7 9 Nbd2 c5

10 Ne1 Qc7 11 Rc1 Bxg2 12 Nxg2 Qb7 13 Ne3 cxd4 14 Bxd4 Nc5 15 Qc2 Nce4 16 Nxe4 Nxe4 17 Qb2 e5 18 Bc3 Bg5 19 f4 exf4 20 gxf4 Bf6 21 Bxf6 Nxf6 22 Rcd1 Qe4 23 Rf3 Nh5 24 Nd5 Rae8 25 Kf2 Qf5 26 Rg1 f6 27 Qb1 Qc8 28 Qd3 f5 29 Qc3 Kh8 30 Rh3 Nf6

31 Rxg7 Kxg7 32 Rg3+ Kh6 33 Nxf6 Re6 34 Rg5 Qc5+ 35 Kf1 and wins.

Przepiórka (as well as Reinfeld and Chernev) stated that the game ended 35 Kf1 Re3 36 Ng4+ fxg4 37 Qg7 mate, whereas Black resigned at move 35 according to pages 34-35 of Schachjahrbuch 1914 I Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914).

It may be felt that calling the game ‘one of the most significant in the history of chess’ is an exaggeration, but the play is certainly an early illustration of hypermodern tenets.

When was the term ‘hypermodern chess’ first used? The earliest citation we can offer at present is in the booklet Am Baum der Schacherkenntnis by S. Tartakower (Berlin, 1921). Pages 15-16 have an article entitled ‘Das hypermoderne Schach’.

(4140)

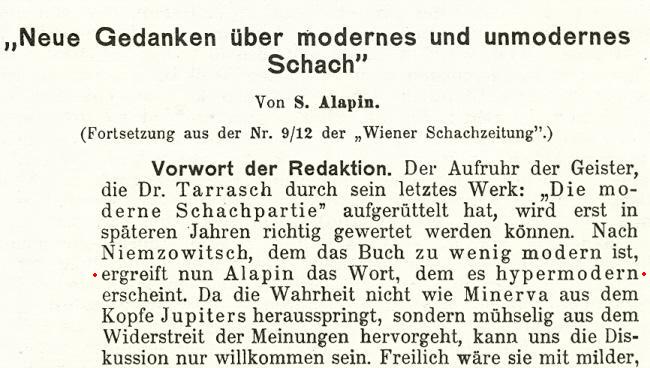

As regards the word ‘hypermodern’ on its own, we now offer passages from pages 253 and 265 of the August-September 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung (respectively the magazine’s introduction to an article by Alapin and the relevant part of that article):

(5561)

In two letters to us dated 21 August 1974 and 13 October 1975 Chernev discussed a 1915 Capablanca loss in a simultaneous exhibition …

‘... in which a high-school boy (whom I knew) won by some Nimzowitsch ideas which were new then to the world – and possibly even to Nimzowitsch.

... Look at it carefully, and you’ll see why I was startled.’

The game was played in a simultaneous exhibition (+48 –5 =12) in the Auditorium of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and was published on page 46 of the March 1915 American Chess Bulletin:

José Raúl Capablanca – Max Wolfson

Brooklyn, 12 February 1915

Queen’s Fianchetto Defence

1 d4 e6 2 c4 b6 3 e4 Bb7 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 Bd3 Bb4 6 Qe2 d6 7 f4 Qe7 8 Nf3

8...c5 9 d5 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 Na6 11 e5 Nd7 12 dxe6 Qxe6 13 f5 Qe7 14 e6 fxe6 15 fxe6 Nf6 16 Ng5 O-O-O 17 Nf7

17...Bxg2 18 Rg1 Bf3 19 Qxf3 Qxe6+ 20 Kd1 Qxf7 21 Qa8+ Nb8 22 Bf5+ Nd7 23 Be4 Ne5 24 Bd5 Qd7 25 a4 Nc6 26 a5 Nxa5 27 Rxa5 bxa5 28 Bf4 Rde8 29 Kc1 Re7 30 Kb2 Rhe8 31 Bg3 Re2+ 32 Ka3 R8e3 33 Rc1 Rd3 34 Be1 Rde3 35 Rb1

35... Ra2+ 36 Kxa2 Qa4+ 37 White resigns.

On page 2 of its 13 February 1915 issue the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported:

‘Max Wolfson, the bright-faced captain of the well-nigh invincible team at Boys High, must be regarded as the real hero of the occasion. Single-handed he engaged the famous master opposed to him and, after playing an irregular defense, which led to a most complicated game, succeeded in forcing the Cuban’s resignation after 36 moves. Capablanca gave in when he faced a mate in two [sic] moves, and the sensational sacrifice of a rook, which accompanied it, elicited from him the remark “Very fine”.’

(3008)

The title of C.N. 3008 was ‘Anticipating Nimzowitsch?’, and the question mark has its purpose. For instance, Nimzowitsch had expounded certain ideas several years before the Capablanca v Wolfson game was played. See Nimzowitsch’s My System and, above all, the outstanding book Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012).

Regarding the Capablanca game and a subsequent draw by Wolfson against Boris Kostić, see Max Wolfson: Unwitting Pioneer by Olimpiu G. Urcan, an article published at the Chess Café in April 2010. Mr Urcan produced a follow-up article on Wolfson, ‘Unwitting Pioneer’, on 7 June 2018.

Two or three years before the Capablanca v Wolfson game was played, the word ‘hypermodern’ had begun to appear in German chess literature. As mentioned in Earliest Occurrences of Chess Terms, page 265 of the August-September 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung had the following in an article by S. Alapin entitled ‘Neue Gendanken über modernes und unmodernes Schach’:

‘Die von Niemzowitsch als angeblich “modern” bezeichnete Holländische Verteidigung 1 d4 f5 “gilt” gerade in “moderner” Zeit als durch 2 e4! fe 3 Sc3 Sf6 4 Lg5 c6 6 f3! widerlegt. Wenn Niemzowitsch hiemit nicht einverstanden ist, so hätte er seine diesbezügliche, also “hypermoderne” Anschauung variantenmäßig begründen sollen?’

The word ‘hypermodern” also appeared in the Editor’s preface to the article, on page 253.

Aron Nimzowitsch

Our above-mentioned article also gave the following English-language citations:

Oxford English Dictionary: ‘The Hyper-moderns are the greatest opponents of routine play.’ Modern Ideas in Chess by R. Réti, translated by J. Hart (London, 1923), page 122.

Oxford English Dictionary: ‘What is claimed as hyper-modern turns out to be ... respectably medi[a]eval.’ BCM, September 1923, page 338.

The same page of the BCM, the item being a review by P.W. Sergeant of Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess, referred to Réti discussing ‘the school of the Hyper-moderns’ and also contains the remark ‘But this is scarcely hyper-modern’.

Richard Réti

From page 81 of P.W. Sergeant’s Championship Chess (London, 1938):

Concerning Gyula Breyer, and his alleged remark that after 1 e4 White’s game is in the last throes see Breyer and the Last Throes.

Gyula Breyer

The above photograph first appeared in C.N. 7812, courtesy of Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany).

For an historical article on 1 e4 Nf6 see Alekhine’s Defence.

Alexander Alekhine

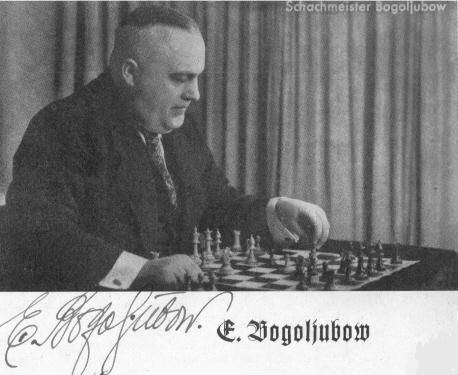

It is not always clear who should be regarded as a hypermodern player. C.N. 653 mentioned the case of Efim Bogoljubow, pointing out that on page 106 of The Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942) Reinfeld described Capablanca v Bogoljubow, London, 1922 as the Cuban’s ‘first encounter with an outstanding Hypermodern master’. However, we added that a random check of tournament books of some of Bogoljubow’s greatest triumphs in the 1920s indicated that his opening play was extremely classical, with barely an Indian Defence, Réti Opening, etc. in sight.

Efim Bogoljubow

C.N. 815 (see page 187 of Chess Explorations) reported that in the 1920s there was discussion of how much newness there was in the ‘Hypermodern Revolution’ and whether much of it was skilful propaganda, and we commented that the earliest article known to us which expressed doubts about the ‘Revolution’ was by Carlo Salvioli in L’Italia Scacchistica, February 1926, pages 25-29. A French translation was published on pages 49-53 of the March 1926 La Stratégie. In support of his case the writer quoted Boris Kostić in Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, October 1925, page 441: ‘In my opinion the term “hypermodern game” is nothing but an empty word devoid of sense.’

Frank Marshall, for his part, objected to more than just the term. As mentioned in C.N. 2877, on pages xi-xiv of his book Chess Masterpieces (New York, 1928) he discussed various proposals for ‘eliminating the so-called hypermodern style’, the latter term ostensibly meaning for him ‘the tendency on the part of many of the grand masters to adopt an extremely close style of play, which involves a keen desire on the part of both players to avoid incurring the slightest risk’. Of the solutions available, Marshall was inclined to favour balloting:

‘The balloting for openings is of course an old plan in checkers or draughts, but I do not agree with those who think that if adopted in chess matches it would sooner or later lead to a large proportion of draws. In any event it should not be a great hardship for two players to have to play White and Black alternately in selected openings, and I am certain that the public would exhibit a lively interest in a contest where they were sure to see a large number of seldom-played openings which will give a welcome variety after the monotony of the Queen’s Pawn Game.’

Following on from C.N. 2877, the following appeared as C.N. 2880:

From Tim Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA):‘Marshall's disparaging comment about “the monotony of the Queen’s Pawn Game” in C.N. 2877 struck me as slightly odd. Didn’t Marshall, when White, play 1 d4 about 90% of the time? (This percentage I gleaned from a very brief and cursory look at the 1,087 Marshall games contained in Chess Base’s Big Database 2002, triggered by the memory of reading when I was young that Marshall was known as a Queen’s Pawn player.)’

Marshall was indeed essentially a 1 d4 player, at least in tournament and match play. His comments in Chess Masterpieces were written in the immediate aftermath of the 1927 world championship match, and below is the paragraph preceding the one quoted in C.N. 2877:

‘Another feasible suggestion is that of balloting for openings. Of the 34 games played in the Capablanca-Alekhine match 32 were Queen’s Gambit Declined, one Queen’s Pawn and one French Defence. All the games were of the type termed “close” and as Mr Howell stated in the American Chess Bulletin in his interesting review of the championship match, “the match taught us very little with regard to the Queen’s Gambit Declined”.’

A few more quotations:

‘In my opinion there are only two really good opening moves, viz.: Pawn to King’s fourth and Pawn to Queen’s fourth.’

Source: Chess Openings by F.J. Marshall (Leeds, 1904), page 23.

And from the same book (page 25), at the start of the section on the Queen’s Gambit:

‘The attack and defence emanating from this classical opening produce some of the most beautiful chess it is possible to obtain. The Queen’s Gambit possesses the merit of being the soundest of all the openings.’

Finally, from the Introduction to Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” (New York, 1914):

‘Special prominence is given to the variations of the Queen’s Gambit, because that opening seems to have escaped the tender mercies of the theorists in chess libraries and received less space than its merits deserve, and also because the chess championship of the world, as fought for over the open board in the matches and tournaments of the past 20 years, has depended more upon a working knowledge of the Queen’s Gambit than of any other chess opening.’

A well-known quip is that, firstly, the hypermodern school did not exist and that, secondly, Nimzowitsch founded it, and a number of C.N. items have tried to establish the origins of the remark. The best source available in C.N. 3079 was a vague reference in an “exclusive” article by Vidmar on pages 155-159 of the October 1927 issue of Mundial, a Uruguayan magazine published in Montevideo:

‘Cuando Réti, por medio de una pequeña pero hermosa obrita, trató de hacer que las nuevas ideas fueran comprensibles para la generalidad, se dice que Teichmann manifestó concisa y concluyentemente: “En primer lugar, no existe una escuela hipermoderna, y además, la creó Nimzowitsch”.’

C.N. 3251 added that the remark is to be found on page 4 of Das neuromantische Schach by S. Tartakower (Berlin, 1927):

‘Da wäre schon der Ausspruch des seligen Teichmann viel zutreffender, der auf einige Ausführungen Réti’s im Jahre 1923 mit dem ihm eigenen kernigen Humor erwiderte: “Erstens existiert die hypermoderne Schule gar nicht und zweitens stammt sie von Nimzowitsch!”’

English translation: ‘... the remark of the late Teichmann, who replied to some of Réti’s statements in 1923 with his own brand of pointed humour: “First, the hypermodern school does not actually exist, and secondly it originates with Nimzowitsch”.’

Savielly Tartakower

C.N. 5006 added that Reinfeld also gave the remark on page 129 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess (New York, 1960):

‘It took Nimzowitsch 20 years of tireless preaching to achieve acceptance. So great a master as Teichmann commented dourly that “in the first place there is no Hypermodern School, and in the second place Nimzowitsch is its founder”. This was a more or less polite way of saying that Nimzowitsch was crazy.’

That last remark of Reinfeld’s seems far-fetched, and it is unclear why he affirmed that Teichmann made the remark ‘dourly’. The same C.N. item added that Reinfeld on Nimzowitsch can be a strange spectacle. For example, also on page 129 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess he wrote: ‘By the time Nimzowitsch was 20, he had perfected his system.’ In his revised edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System (Philadelphia, 1947) Reinfeld stated (page xxi) that ‘by 1906, when he was only 20, Nimzowitsch had definitely become a master of the very first rank’.

As pointed out in C.N. 9357, below is a remark by Fred Reinfeld on page 106 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘Teichmann, a stalwart of the old school, made the surly comment that in the first place there was no Hypermodern school, and that in the second place Nimzowitsch was its founder.’

For a reliable account of Nimzowitsch’s development, readers today can rely on a magnificently researched book, Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012).

Peter Morris (Kallista, Australia) notes on page 256 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952) the following annotation in the game Paulsen v Rosenthal, Vienna, 1873, after 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 Bc5 4 Bg2:

‘In an open game, and at a time when chess went through its “heroic period”, White applies a principle which was later on to be brought to the fore by the masters of “hyper-modern” chess, Breyer, Réti, Nimzowitsch, Bogoljubow, and up to a point by Alekhine and others, namely, control of the centre instead of its occupation.’

The passage is particularly interesting for its reference to Bogoljubow; we have expressed doubts as to whether he should be regarded as a hypermodern player.

(8003)

Wanted: the newspaper article referred to by Edward Lasker on page 159 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood (Philadelphia, 1942):

‘As Horace Bigelow, who covered the tournament for one of the New York papers, remarked at the time: “The modern school came, saw and succumbed.”’

From page 92 of Lasker’s The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950):

‘... the amusing though erroneous comment of a chess columnist was: “The New School came, saw, and succumbed.”’

(8916)

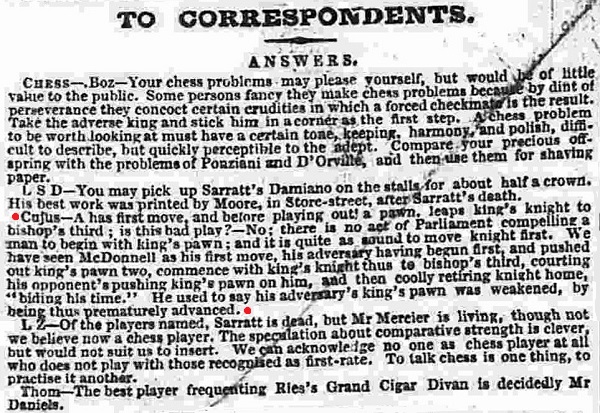

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In Bell’s Life in London, 13 November 1842 George Walker recalls in a reply to a correspondent that Alexander McDonnell (1798-1835) had played an unusual variation of Alekhine’s Defence:

“We have seen McDonnell as his first move, his adversary having begun first, and pushed out king’s pawn two, commence with king’s knight thus to bishop’s third, courting his opponent’s pushing king’s pawn on him, and then coolly retiring knight home, “biding his time”. He used to say his adversary’s king’s pawn was weakened, by being thus prematurely advanced.”

This commentary on the variation 1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Ng8 suggests that McDonnell possessed some understanding of what we would now regard as hypermodern principles of play.

I note your feature article on Alekhine’s Defence. Had Allgaier already explained any such principles in the course of his analysis?’

Below is the passage by Walker referred to, from page 2 of the 13 November 1842 edition of Bell’s Life in London:

Mr Townsend notes that the item can also be viewed at the Chess Archaeology website as part of the Jack O’Keefe Project. (The Project, we add, represents an astounding amount of work of great value.)

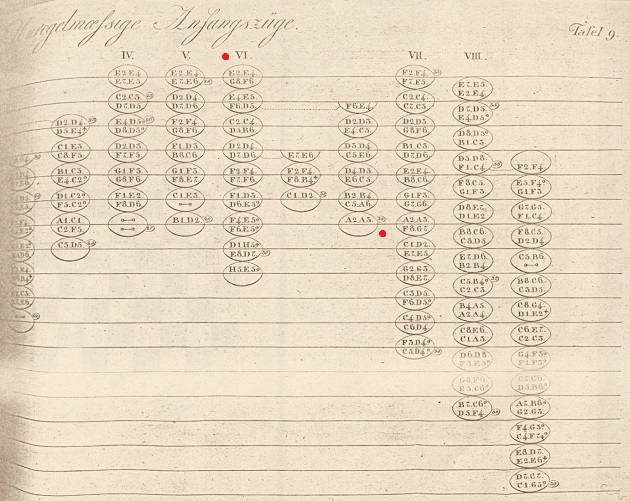

The answer to our correspondent’s question about Allgaier is that no explanation of principles was offered when the moves 1 e4 Nf6 were given in Tafel 9 of his book Neue theoretisch-praktische Anweisung zum Schachspiele (Vienna, 1819):

The relevant notes (30, 31 and 32) can be read in the Google Books scan of the work, on page 108.

The connection between Alexander McDonnell and hypermodernism is intriguing.

(9667)

Peter Morris adds the name of Louis Paulsen. A popular account of some aspects of his contribution to chess theory is on pages 187-189 of Chernev’s The Chess Companion. Further references will be welcome.

‘It seems only a few years ago that the Hypermodern School, headed by Alekhine, Réti, Nimzowitsch, Bogoljubow and Breyer, infused a new vitality and profundity into the then extant chess theories.’

Source: Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933), page 96.

The omission of Tartakower may be considered a simple oubli.

(10031)

From our feature article on Irving Chernev:

Chernev presented the draw Bernstein v Nimzowitsch, St Petersburg, 1914 (published on pages 249-255 of the September-November 1914 Wiener Schachzeitung) in a column entitled ‘Exciting Drawn Games’, on pages 257-259 of the November 1935 Chess Review, with this introduction:

‘The following game is, in the estimation of the writer, the most brilliant drawn game ever played, as well as one of the finest of chess masterpieces. Sparkling as this gem is, it needed the masterly annotations of Georg Marco to bring out its full beauty. So dazzling were its coruscations as to blind other eminent annotators – Dr Tarrasch, Herr Emmerich [sic – Emmrich], Bogoljubow, Dr Tartakower, etc. – so that they placed exclamation points where question marks belonged.

Historically, the game is important as being one of the first wherein hypermodern principles are essayed, in this case an illustration of control of the centre squares, foregoing their occupation by pawns.’

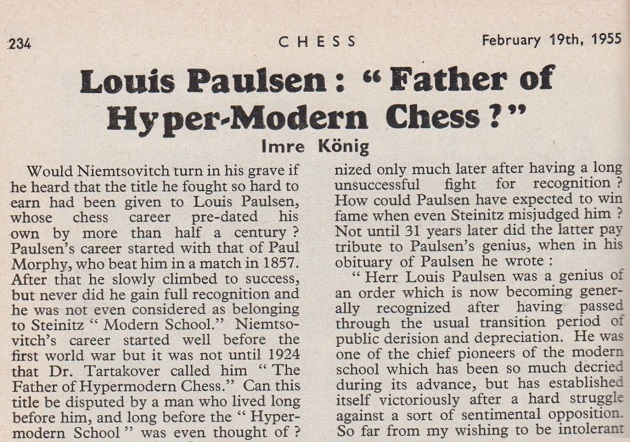

C.N.s 2323, 4773 and 8687 discussed the nickname ‘The father of modern chess’. Concerning ‘The father of hypermodern chess’, citations for Nimzowitsch (and, even, Tartakower) are easily found, but there is also an article about Louis Paulsen by Imre König on pages 234-236 of CHESS, 19 February 1955:

(10463)

As shown above, C.N. 1157 (see page 95 of Chess Explorations) quoted this passage from page 360 of the August 1926 BCM:

John Townsend queries the statement that Staunton, after losing an informal match to Saint-Amant, ‘worked out behind closed doors, in company with very strong players like Cochrane, Popert, etc., the openings which he proposed to play in the second match’:

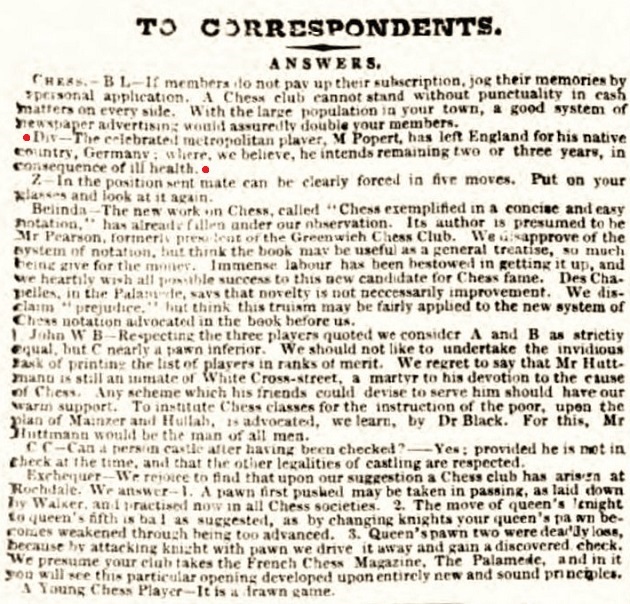

‘There is strong evidence that both Cochrane and Popert were abroad during the period in question. Preparation “behind closed doors” is claimed to have taken place between the two Staunton v Saint-Amant matches, i.e. between May and November 1843. However, page 2 of Bell’s Life in London, 11 September 1842 noted that Popert had already left England for his native Germany, “where, we believe, he intends remaining two or three years, in consequence of ill health”:

John Cochrane’s departure for India was also reported some time before the first match, in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1844, page 127.’

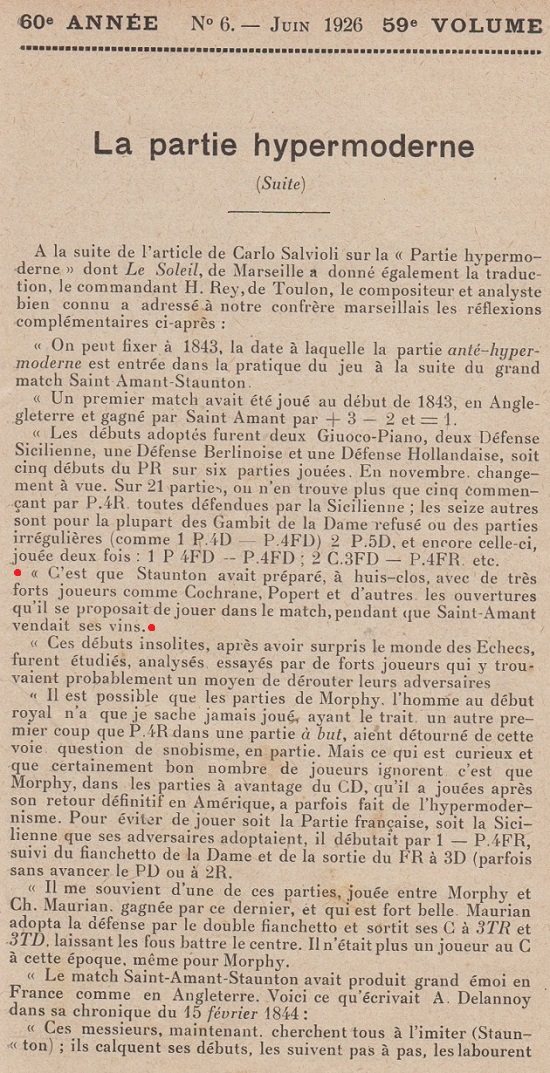

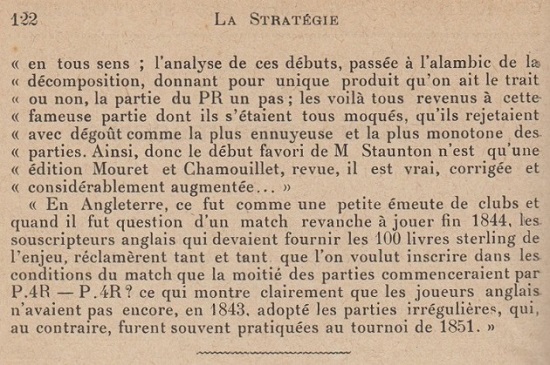

Pages 49-53 of the March 1926 edition of La Stratégie had a translation by A. Goetz of an article by Carlo Salvioli about hypermodern chess from pages 25-29 of L’Italia Scacchistica, February 1926. As shown below, the follow-up article (La Stratégie, June 1926, pages 121-122), consisted of a response submitted by Commandant H. Rey to the Marseilles newspaper Le Soleil, where the Salvioli article had also appeared in translation:

(11729)

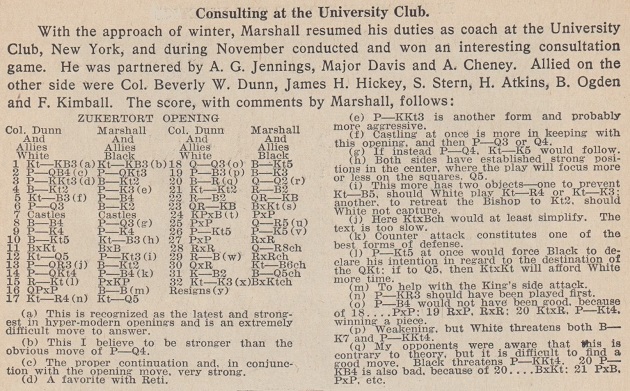

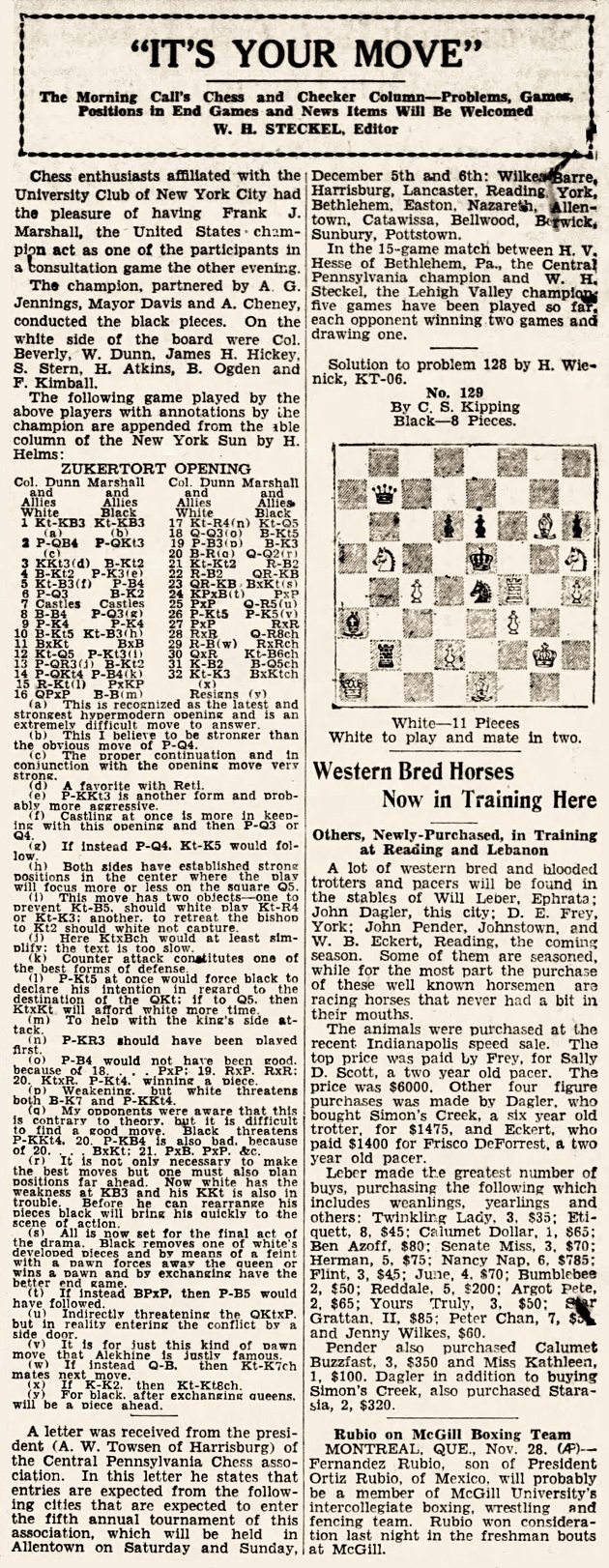

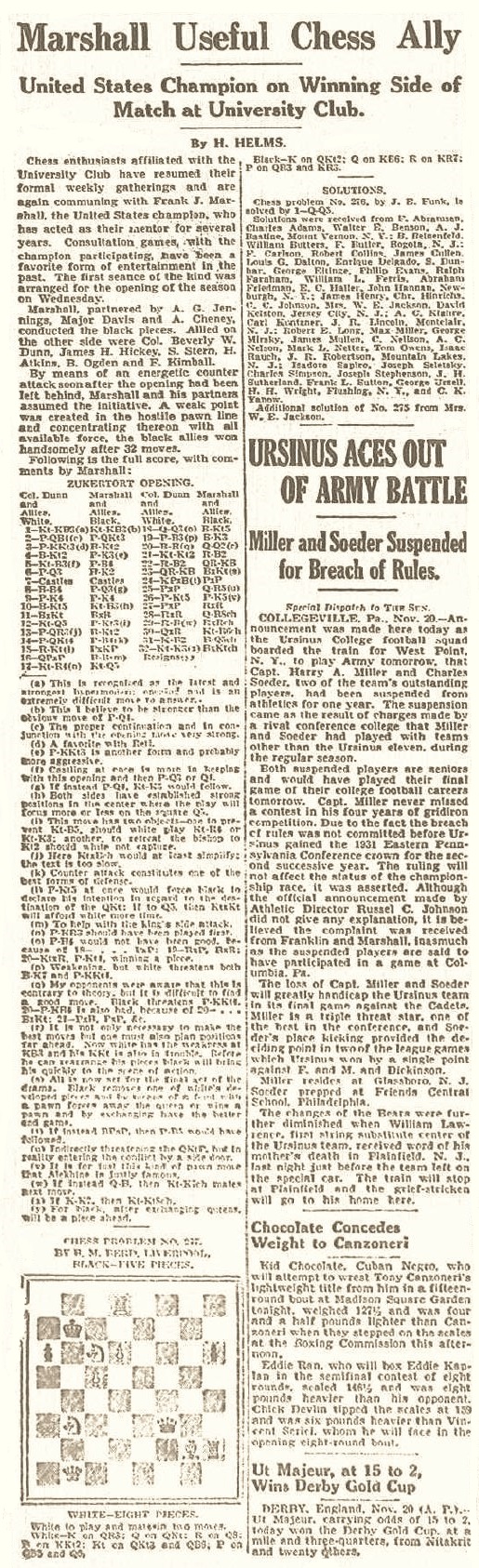

In the item below, from page 7 of the January 1932 American Chess Bulletin, a comment by Marshall about 1 Nf3 is worth noting:

‘This is recognized as the latest and strongest in hyper-modern openings and is an extremely difficult move to answer.’

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 g3 Bb7 4 Bg2 e6 5 Nc3 c5 6 d3 Be7 7 O-O O-O 8 Bf4 d6 9 e4 e5 10 Bg5 Nc6 11 Bxf6 Bxf6 12 Nd5 g6 13 a3 Bg7 14 b4

14...f5 15 Rb1 fxe4 16 dxe4 Bc8 17 Nh4 Nd4 18 Qd3 Bg4 19 f3 Be6 20 Bh1 Qd7 21 Ng2 Rf7 22 Rf2 Raf8 23 Rbf1 Bxd5 24 exd5 cxb4 25 axb4 Qa4 26 b5 e4 27 fxe4 Rxf2 28 Rxf2 Qa1+ 29 Rf1 Rxf1+ 30 Qxf1 Nf3+ 31 Kf2 Bd4+ 32 Ne3 Bxe3+ 33 White resigns.

The notes after (q) have yet to be found.

(11342)

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) has found Marshall’s complete notes on page 10 of the Allentown Morning Call, 29 November 1931:

We can add that the Sun column referred to was on page 40 of the 20 November 1931 edition:

(11347)

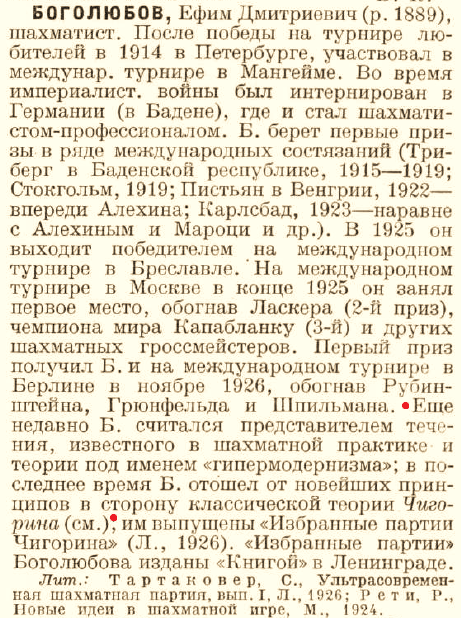

As shown above, a few C.N. items have discussed whether or not Efim Bogoljubow was a hypermodern player. Now, Dmitriy Komendenko (St Petersburg, Russia) submits the entry on the master in volume six of the first edition (1927) of the reference work Большая советская энциклопедия:

The highlighted passage asserts that until recently Bogoljubow had been regarded as a representative of hypermoderism but that, of late, he had moved away therefrom to the classical theory of Chigorin:

‘Ещё недавно Б. считался представителем течения, известного в шахматной практике и теории под именем “гипермодернизма”; в последнее время Б. отошёл от новейших принципов в сторону классической теории Чигорина.’

(11901)

Addition on 7 September 2023:

C.N. 508 gave this correspondence game (E. Davis v A.J. Knight) from the 1983 booklet The First Grand Open by R. Gillman and J. Hawkes. Neither the d- nor the e-pawn of the winner made any moves:

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 g3 g6 3 b4 Bg7 4 Bb2 a5 5 b5 c6 6 a4 cxb5 7 axb5 d5 8 Bg2 Qb6 9 Bd4 Qd8 10 c4 dxc4 11 Na3 Be6 12 Qa4 O-O 13 O-O h6 14 Nxc4 Nbd7 15 Rfc1 b6 16 Nfe5 Nd5 17 Nxd7 Bxd4 18 Nxf8 Kxf8 19 Rab1 Bg7 20 Ne3 Rb8 21 Nxd5 Bxd5 22 Qf4 Ba2 23 Ra1 Bxa1 24 Rxa1 Be6 25 Qxh6+ Kg8 26 Ra4 Qf8 27 Qg5 Rc8 28 Bc6 Bb3 29 Rh4 a4 30 Qe5 f6 31 Qe3 Rb8 32 Qd3 Kg7 33 Rg4 Qf7 34 Be4 g5 35 h4 a3 36 hxg5 f5 37 Qc3+ Kg6 38 Rh4 fxe4 39 Rh6+ Kf5 40 Qe3 Resigns.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.