Edward Winter

See C.N. 7365 below.

Two entertaining games caught our eye in issue 170 of SSKK Bulletinen (4/1982). SSKK, as every schoolboy knows, stands for Sveriges Schackförbunds Korrespondensschackkommitté.

Yngve Seger – Harry Andersson

Oldboys-SM, 1962 (Final)

Sicilian Defence

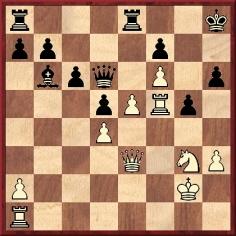

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bc4 g6 7 f4 e6 8 O-O Bg7 9 f5 b5 10 Bb3 e5 11 Nf3 gxf5 12 Ng5 Qb6+ 13 Kh1 Ra7 14 exf5 Rd7 15 Ne6 Rg8 16 Bg5 Bb7 17 Bxf6 Bxf6 18 Bd5 b4 19 Ne4 Ke7 20 Nxf6 Kxf6

21 Qh5 fxe6 22 fxe6+ Kg7 23 Qg5+ Kh8 24 Qxg8+ Kxg8 25 e7+ and Black resigned, just in time to keep the game a miniature. [Regarding this remark of ours, see the comments in C.N. 471 by W.H. Cozens.]

The second game has an unusual queen sacrifice which exploits White’s neglect of proper development.

Bo Wiker – Kenth Sandéhn

Lag-SM, 1982

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 O-O 8 Bd3 c4 9 Be2 Qa5 10 Bd2 Nbc6 11 Nh3 f6 12 f4 Bd7 13 Rf1 b5 14 Rf3 Qa4 15 Bd1 b4 16 exf6 Rxf6 17 Ng5 h6 18 Rh3

18...Qxa3 19 Rb1 Qa2 20 Rxb4 Nxb4 21 cxb4 Raf8 22 Nf3 c3 23 Be3 Nf5 24 Bf2 Qb2 25 Ne5 Bb5 26 Qf3 Nxd4 27 Bxd4 Rxf4 28 Qxc3 Rf1+ 29 Kd2 Rxd1+ 30 Kxd1 Rf1+ 31 White resigns.

(282)

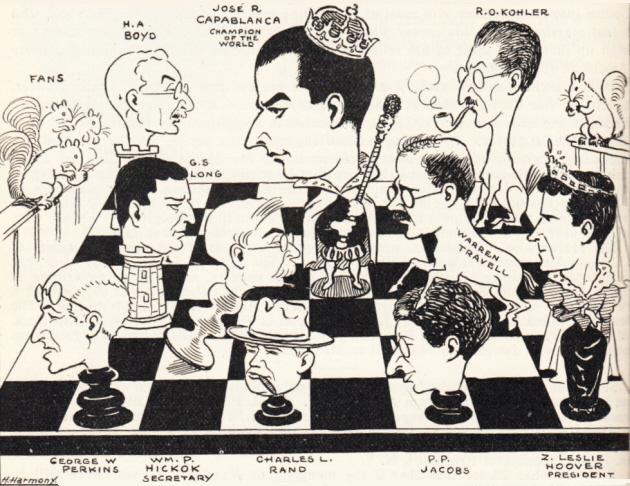

One can never take anything for granted. For a long time we assumed that Capablanca never played a single correspondence game in his life. It seemed about as probable as Elijah Williams playing blitz. But some issues of Capablanca-Magazine have an advertisement in which readers are invited to play postal chess against Capablanca (five dollars) or J. Corzo (three dollars). In the more expensive case, all-comers had to write to Apartado 1013, New York. Presumably at least some games were played, but have any survived?

(685)

From pages 53-54 of our 1989 book on Capablanca:

A number of issues of Capablanca-Magazine carried an advertisement inviting readers to play chess by correspondence against either Capablanca or Juan Corzo. The charges were five and three dollars respectively, the address for Capablanca being given as Apartado 1013, New York. Some commentators have given the impression that Capablanca was wealthy, but this scarcely seems likely. In this connection it may be noted that the February 1915 American Chess Bulletin (page 46) contained the following paragraph: ‘The champion is also ready to take private pupils, special arrangements at half price being made for a series of ten lessons. ... Amateurs desiring to play chess with Mr Capablanca by correspondence can do so at the rate of $10 for two games conducted simultaneously.’ It has not been possible to discover further information about these activities, such as they may have been, or, indeed, to find scores of correspondence games played by Capablanca at any stage of his career.

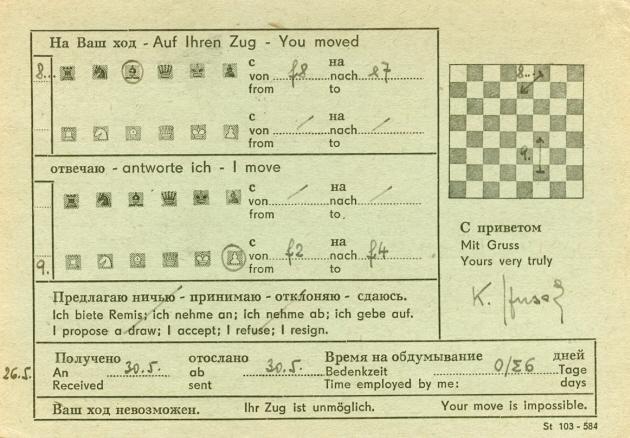

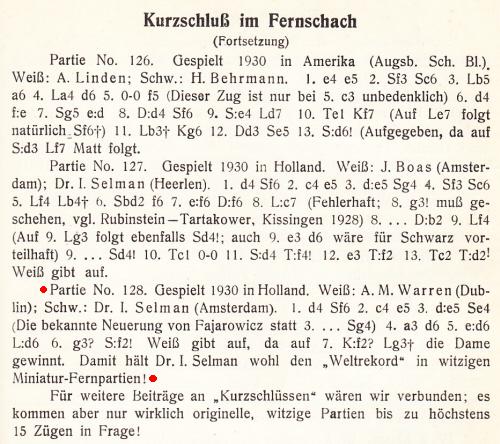

We would like confirmation that this mini-game was indeed played, and that Black’s sixth move did cause his opponent to resign.

Warren – Selman

Correspondence, 1930

Budapest Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ne4 4 a3 d6 5 exd6 Bxd6 6 g3 Nxf2.

‘Resigns’, writes Soltis in Chess Lists. ‘Resigns’ writes Chernev in 1000 Best Short Games of Chess. ‘And Black wins’ writes Chernev in Wonders and Curiosities of Chess. The Chess Digest booklet The Budapest Defence (page 35) gives Chernev credit for the line.

(905)

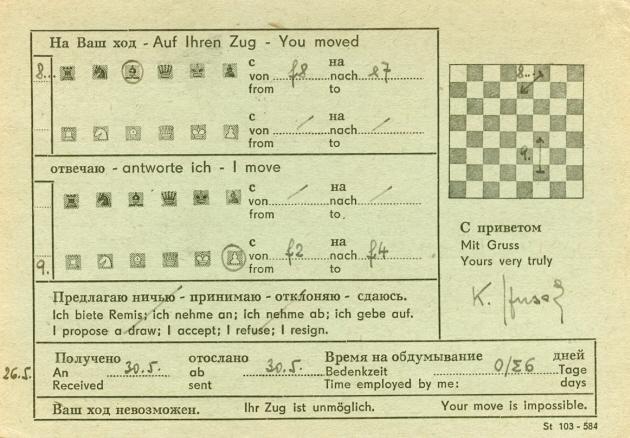

It seems that Black’s sixth move did indeed provoke his opponent’s immediate resignation. Rob Verhoeven (The Hague, the Netherlands) sends us a photocopy of the score of the game in Fernschach, September 1931, page 71.

(933)

The game’s appearance on page 71 of Fernschach, September 1931:

(7694)

Regarding the correspondence game discussed in C.N. 7694 Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) writes:

‘The “I. Selman” of Amsterdam mentioned by Fernschach was John Selman Jr, the Saavedra expert, who called himself “Junior” to avoid being confused with his elder brother Dr Johan Selman. The latter was also a reasonably strong amateur chessplayer, who conducted a chess column in the Limburgs Dagblad. The editor of Fernschach apparently did not notice that the I. Selman in game 127 lived in a different city in the south of the Netherlands and thought that they were the same person.’

(7717)

Concerning the Warren v Selman correspondence brevity Harrie Grondijs writes:

‘The game appears to have been played by J. (Jan) Selman Senior after all, and not by his younger brother John. In Spirit, a recreational house magazine for the staff of the BPM (Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij), John Selman Junior, an employee, conducted a column from October 1937 until the War years (taking it up again after the War). Before October 1937 he was on the editorial board of the magazine, and in the chess corner (“Schaakhoek”) in the January 1937 issue the following appeared (with the game misdated 1933):

In the early 1930s both of the Selman brothers studied and/or worked in Amsterdam and even played for the same club team. In a letter dated 25 February 1940 in my possession Selman Junior wrote:

“In the past when my eldest brother and I were members of the same chess club in Amsterdam, next to each other in the same team, this caused considerable confusion ...”

I now believe that the miniature games 127 and 128 given by Fernschach in 1931 (where White was named as A.M. Warren in the latter) were played by Jan Selman Senior.’

(7771)

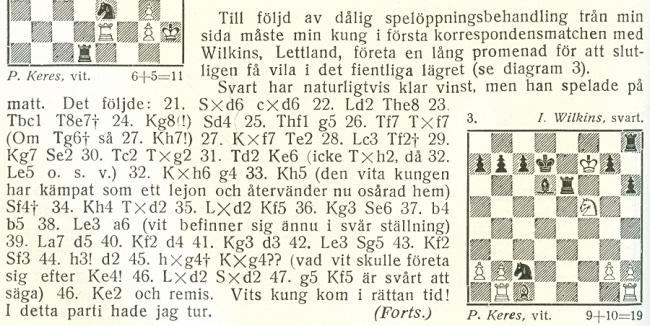

From Carl-Eric Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden):

‘I am especially interested in the games of Paul Keres and would be very grateful for any help in finding more examples of his correspondence play. (He probably played about 500 postal games.) He wrote on page 15 of Ausgewählte Partien 1931-1958 that at one time he had 150 games running at the same time, and when he won the IFSB championship in 1935 he was involved in 70 games simultaneously.

The following game (Keres-E. Verbak, correspondence, 1932) was published in Fernschach number 2 in 1935: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Be3 dxe4 4 Nd2 f5 5 f3 exf3 6 Ngxf3 Nf6 7 Bd3 c5 8 O-O cxd4 9 Nxd4 f4 10 Rxf4 e5 11 Bb5+ Kf7 12 Qh5+ g6 13 Bc4+:

Here Dr Dyckhoff’s booklet Fernschach-Kurzschlüsse and the book by Ludwig Steinkohl Faszination Fernschach give the continuation 13...Kg7 14 Qh6+! 1-0. “The final position deserves a diagram”, writes Mr Steinkohl.

However, Verbak actually played 13... Ke8 and resigned after 14 Qxe5+ Qe7 15 Qxf6 (Fernschach, which also mentions the variation 13...Kg7 14 Qh6+). According to Valter Heuer’s book on Keres, this game was played between September and October 1932, i.e. when Keres was 16. Heuer also gives the moves 15...Qxe3+ 16 Kh1 Qxd2 17 Re4+ Resigns.’

(936)

As reported in C.N. 978, in 1985 Mr Erlandsson sent us a two-page list of mistakes that he had noted in Faszination Fernschach.

Paul Keres

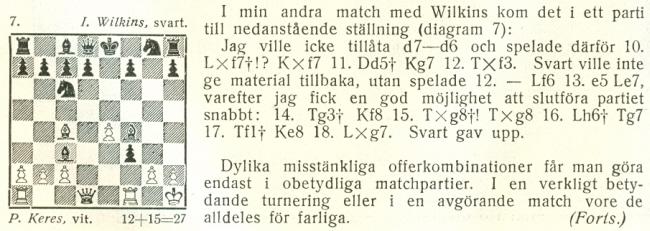

In the context of Keres’ early correspondence chess a name frequently seen is ‘Wilkins’, and two games in which Keres was White have been widely published as follows:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nc3 Qh4+ 4 Ke2 Nc6 5 d4 d5 6 Nxd5 Bg4+ 7 Nf3 O-O-O 8 Kd3 f5 9 Nxh4 fxe4+ 10 Kxe4 Bxd1 11 Bd3 Re8+ 12 Kxf4 Bd6+ 13 Kg5 h6+ 14 Kf5 Nxd4+ 15 Kg6 Bxc2 16 Bxc2 Nxc2 17 Rb1 Ne7+ 18 Nxe7+ Rxe7 19 Nf5 Re6+ 20 Kf7 Kd7 21 Nxd6 cxd6 22 Bd2 Rhe8 23 Rbc1 R8e7+ 24 Kg8 Drawn.

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 g5 5 d4 g4 6 Bc4 gxf3 7 O-O Bg7 8 Bxf4 Bxd4+ 9 Kh1 Bxc3 10 Bxf7+ Kxf7 11 Qd5+ Kg7 12 Rxf3 Bf6 13 e5 Be7 14 Rg3+ Kf8

15 Rxg8+ Resigns.

They are usually dated circa 1933. In the case of the second game see, for instance, pages 86-87 of Paul Keres Chess Master Class by Y. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1983).

However, in articles entitled ‘Muntrationer från min korrespondenspraktik’ in the Swedish magazine Schackvärlden in 1935 (August, page 418 and September, page 522) Keres gave the conclusion of each game as follows:

Page 168 of the July 1933 Deutsche Schachzeitung reported that Keres was successful in the correspondence match:

‘Pernau. Paul Keres-Pernau gewann einen Fernwettkampf gegen J. Wilkins mit +7 –1 =2 ...’

A position from a third game between the two players was given on page 207 of the July 1935 issue of the German magazine.

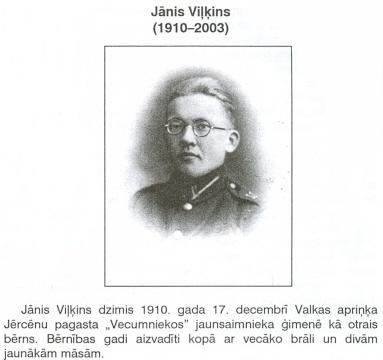

Although Keres too used the spelling ‘Wilkins’, the player in question was the Latvian Jānis Viļķins. The illustration below comes from Korespondencšahs Latvijā 1877-1944 by Ģ. Salmiņš (Liepāja, 2005):

(5477)

From page 47 of the December 1944 CHESS:

M. Ellinger – Rev. A.P. Durrant

P.C.C. League tournament No. 14

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Ne2 Nf6 3 e5 Nd5 4 c4 Nb4 5 Nbc3 Nd3 mate.

‘Rarely can Mr Ellinger, a normally very sound and strong player, have gone so badly astray!’

(1045)

Mordecai Morgan – James Ephraim Narraway

Correspondence

Queen’s Gambit Declined

(Notes from the Philadelphia Inquirer)

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 Nf6 4 Nc3 c5 5 cxd5 (‘Morgan’s new variation. It might well be christened “Morgan’s Gambit in the Queen’s Pawn Opening”. The move leads to many beautiful and complicated positions’.) 5...cxd4 6 dxe6 dxc3 7 exf7+ Ke7 8 Qc2 Qd5 9 bxc3 (‘Morgan now considers that his correct continuation was 9 g3, followed by 10 Bg2.’) 9...Bf5 10 Qb2 Nbd7 11 Bf4 Ne4 12 Nd4 Nb6 13 g4 Bg6 14 Bg2 Kxf7 15 Qc2 Bc5 16 Rd1 Rhe8 17 h4 h6 18 Rh3 Qc4 19 Rf3 Nf6 20 Qb3 Be4 (‘Morgan highly compliments his opponent for his excellent judgement in conducting the balance of the game. Black likely has a winning position, but to win the game required exceptionally able play.’) 21 Rg3 Bxg2 22 Rxg2 Re4 23 e3 Rae8 24 Qxc4+ Nxc4 25 Ne2 Ne5 26 g5 Nf3+ 27 Kf1 Nxh4 28 gxf6 Nxg2 29 Kxg2 Kxf6 30 Nd4 g5 31 Bh2 Rc8 32 Rd3 a6 33 Kf3 Re7 34 Nb3 h5 35 Nxc5 Rxc5 36 Bd6 Rf5+ 37 Kg3 h4+ 38 Kg2 Rh7 39 e4 h3+ 40 Kg1 Rb5 41 a4 Rb1+ 42 Kh2 Rb2 43 Bg3 g4 44 Rd6+ Ke7 45 Rg6 Ra2 46 Rb6 Ke8 47 Rb4 Rf7 48 Kg1 Ra1+ 49 Kh2 Rd7 50 Be5 Rd2 51 White resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, December 1915, page 246.

(1756)

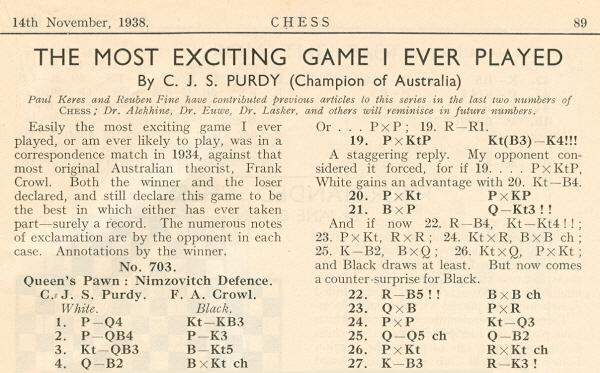

Frank Crowl regularly appeared in Purdy’s writings, and in C.N. 1859 (see pages 83-84 of Chess Explorations) we gave a spectacular correspondence game between the two players. Page 259 of our book noted that Purdy annotated the game on pages 89-90 of the 14 November 1938 issue of CHESS, calling it ‘easily the most exciting game I ever played, or am ever likely to play ... Both the winner and the loser declared, and still declare, this game to be the best in which either has ever taken part – surely a record’.

Another set of Purdy annotations to the game was reproduced on pages 19-22 of How Purdy Won by C.J.S. Purdy, F. Hutchings and K. Harrison (Cammeray, 1983). Below is the bare game-score:

Cecil John Seddon Purdy – Frank Arthur Crowl

Correspondence, 1934-35

Nimzo-Indian Defence

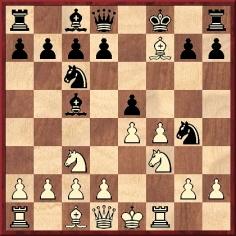

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qc2 Bxc3+ 5 Qxc3 Ne4 6 Qc2 f5 7 e3 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 Ne2 Qh4 10 O-O Nc6 11 g3 Qf6 12 a3 Ng5 13 f3 O-O 14 Bd2 Rae8 15 Bc3 Qh6 16 h4 Nf7 17 e4 g5 18 Kg2 g4 19 fxg4

19...Nce5 20 dxe5 fxe4 21 Bxe4 Qg6

22 Rf5 Bxe4+ 23 Qxe4 exf5 24 gxf5 Nd6 25 Qd5+ Qf7 26 exd6 Rxe2+ 27 Kf3 Re6 28 g4 h5 29 dxc7 hxg4+ 30 Kxg4 Rc6 31 Rg1 Kh7 32 Qxf7+ Rxf7 33 Re1 Rxc4+ 34 Kg5 Rc5 35 Re5 Rg7+ 36 Kh5 Rc6

37 f6 Rxf6 38 Rg5 Rh6+ 39 Kg4 Rxg5+ 40 Kxg5 Rc6 41 Be5 d5 42 Kf5 b5 43 b4 a6 44 Kf4 Kg6 45 h5+ Kxh5 46 Ke3 Resigns.

From pages 64-67 of How Purdy Won (Cammeray, 1983) by C.J.S. Purdy, F. Hutchings and K. Harrison:

F.L. Vaughan – C.J.S. Purdy

Correspondence, -1946

Grünfeld Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bf4 Bg7 5 e3 c5 6 dxc5 Qa5 7 cxd5 Nxd5 8 Qxd5 Bxc3+ 9 bxc3 Qxc3+ 10 Ke2 Qxa1 11 Be5 Qc1 12 Bxh8 Be6 13 Qxb7 Qc2+ Drawn.

Purdy comments:

‘This game finished in 1946. Eight years later the same game occurred in the crossboard grandmaster tourney of Bucharest 1954, Filip v Pachman. And ten years after that, Pachman played it with Black again, this time against Darga, in the Interzonal, Amsterdam 1964. In the last round of the same tourney it occurred yet a fourth time, in Berger v Bilek.’

(1860)

On pages 36-37 of the 7/2015 New in Chess Nigel Short’s article about chess magazines includes this observation regarding the BCM:

‘Sadly, this once esteemed gazette has barely crawled into the 21st century, on life-support and with reputation threadbare, but, for much of its long existence, with its donnish prose, historical articles and news from distant dominions, it was a very fine read.’

Short also refers to the Australasian Chess Review and Chess World, edited by Cecil Purdy:

‘The first World Correspondence Champion had such an admirable way of explaining games and expressing ideas with great clarity that it is no wonder that Bobby Fischer held him in high regard.’

Fischer’s opinion of Purdy as a teacher and annotator has often been mentioned, and we should like to cite any direct statements made by the American. In the meantime, an extract from the back cover of Purdy’s Guide to Good Chess (Davenport, 2006):

(9561)

In C.N. 239 W.D. Rubinstein (Victoria, Australia) informed us:

‘Purdy told me that Bobby Fischer held his annotations in high esteem, and Fischer made a point of greeting him warmly at Siegen [the 1970 Olympiad] when they met for the first time.’

C.T. Shedden – E.H. Bermingham

Correspondence game, 1911

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 Bc5 4 Nc3 d6 5 f4 Ng4 6 g3 Nf2 7 Qh5 g6 8 Qh6 Nxh1 9 f5 Nd7 10 Bg5 f6 11 Qg7 Rf8 12 Nd5 fxg5 13 fxg6 c6 14 gxh7 cxd5

15 Qg6+ (‘Three pieces down and two others en prise.’) 15...Ke7 16 Bxd5 Nf6 17 Qg7+ Ke8 18 h8(Q) Qe7 19 Qxe7+ Kxe7 20 Qg7+ Ke8 21 Bb3 Bxg1 22 Kd2 Nxe4+ 23 dxe4 Rf2+ 24 Ke1 Rxh2 25 Ba4+ Kd8 26 Qxg5+ Kc7 27 Qe7+ Kb6 28 Qxd6+ Ka5 29 a3 Bf2+ 30 Kd1 Bg4+ 31 Kc1 b6 32 Qb4+ Ka6 33 Bc6 Resigns.

Source: BCM, December 1911, page 462. The magazine wrote: ‘Rarely have we seen such a series of offered sacrifices as in this spirited encounter.’

(2147)

A. Rhode – Willi Schlage

Correspondence game, 1917

Two Knights’ Defence

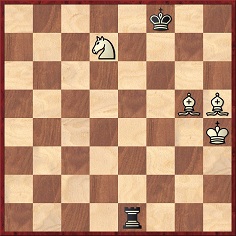

21…Qxf6 22 Qxd7+ (Schlage: ‘The only move. These successive queen sacrifices, which are also the first moves by both queens, are most likely unique in chess literature.’ 22 exf6 is refuted by 22…Rxh3+ and 23…Bc6+.) 22…Kxd7 23 exf6 Rag8 24 Rfd1+ Ke6 25 Nd2 g4 26 Nf1 gxh3 27 Rd3 hxg2+ 28 Kxg2

28…Rh1 29 White resigns.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1917, pages 106-107.

(2197)

Owen Hindle (Cromer, England) submits this blindfold correspondence game:

Norris – Arthur Towle Marriott

Correspondence game

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 f5 5 d4 exd4 6 O-O Bc5 7 Ng5 Nf6 8 Bb3 d5 9 exd5 Na5 10 Re1+ Kf8 11 d6 Nxb3 12 dxc7 Qxc7 13 cxb3 Bd7 14 b4 h6 15 Ne6+ Bxe6 16 bxc5 Kf7 17 Qxd4 Rad8 18 Qb4 g5 19 Nc3 f4 20 f3 Rhe8 21 Na4 a5 22 Qc3 Kg6 23 Nb6 g4 24 Qxa5 gxf3 25 gxf3 Kh7 26 Nc4 Qg7+ 27 Kf2 Bh3 28 Rg1

Black announced mate in four moves.

Source: The Westminster Papers, 1 February 1879, pages 221-222.

The Papers introduced the game as follows: ‘Played, by correspondence, between Mr Norris, of London, and Mr A. Marriott, of Nottingham, the latter playing blindfold.’

(Kingpin, 1997)

A fascinating game which concluded with a configuration of extreme rarity:

H. Treer – Hans Fahrni

Correspondence tournament, 1927-29

Dutch Defence

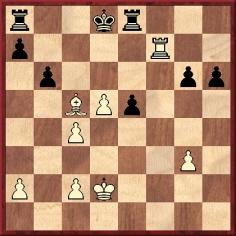

1 Nf3 e6 2 c4 f5 3 g3 c6 4 Bg2 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Nc3 d5 7 d4 Nbd7 8 b3 Bd6 9 Qc2 O-O 10 cxd5 Nxd5 11 Bb2 N7f6 12 Na4 Qe7 13 Rac1 Ne4 14 Rfd1 Nxf2 15 Kxf2 f4 16 Re1 fxg3+ 17 Kg1 gxh2+ 18 Kh1 Bg3 19 e4 Bxe1 20 exd5 Bg3 21 dxc6 e5 22 Qc4+ Kh8 23 Nxe5 bxc6 24 Nc5 Bf5 25 Nxc6 Qe3 26 Rf1 Rae8 27 Bc1

27…Qg1+ 28 Rxg1 hxg1(Q)+ 29 Kxg1 Re1+ 30 Qf1 h5 31 Qxe1 Bxe1 32 Ne7 Bh7 33 Ne6 Re8 34 Bg5 Bb4 35 Nc6 Rxe6 36 Nxb4 Bb1 37 Kf2 Rb6 38 Be7 a5 39 Nc6 a4 40 Nb4 axb3 41 axb3 g5 42 Bf3 g4 43 Bd1 Kg7 44 Nd5 Re6 45 Bh4 Rd6 46 Nf4 Ba2 47 Be7 Rd7 48 Bc5 Kh6 49 Kg3 Rf7 50 Bc2 Kg5 51 Ne6+ Kf6 52 Nd8 Rc7 53 Kf4 h4 54 Kxg4 Rg7+ 55 Kxh4 Rg2 56 Be4 Rg8 57 Nc6 Bxb3 58 d5 Ba2 59 Be7+ Kf7 60 Bg5 Re8 61 Bf3 Re1 62 d6 Ke8 63 Nb8 Be6 64 d7+ Bxd7 65 Bh5+ Kf8 66 Nxd7+

66…Kg8 67 Bf6 Rg1 68 Bd4 Rg2 69 Bf3 Rh2+ 70 Kg3 Rd2 71 Bd5+ Kh7 72 Nf8+ Kh6 73 Be3+ Resigns.

Source: Wiener Schachzeitung, July 1929, pages 214-216.

(2417)

N.N. – Mikhail Chigorin

Correspondence game, Russia (date?)

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 Nc3 b5 7 Bb3 Bg4 8 d3 Qd7 9 Nb1 Nd4 10 Nbd2 Ne6 11 Qe1 Nf4 12 Qe3

12…Bh3 13 gxh3 Ng4 14 Qe1 Nxh2 15 Qe3 Ng4 16 Qe1 Nh6 17 Nb1 Qxh3 18 Bxf4 exf4 19 Nbd2 Ng4 20 Bd5 h5 21 Bxa8 Rh6 22 e5 Rg6 23 Be4 Ne3+ 24 Bxg6 Qg2 mate.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 April 1901, pages 105-106.

(2505)

The game below was published on pages 153-154 of the International Chess Magazine, May 1890, page 153:

Walter Irving Kennard – E.P. Wires

Correspondence game

Steinitz Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 d4 Qh4+ 5 Ke2 d5 6 exd5 Bg4+ 7 Nf3 Qe7+ 8 Kf2 Bxf3 9 Kxf3 Nd8 10 Bb5+ c6 11 dxc6 bxc6 12 Bxc6+ Nxc6 13 Re1 Nxd4+ 14 Qxd4 Qxe1

15 Bxf4 (‘The initiation of a brilliant, ingenious and quite original combination, which reflects the highest credit on Mr Kennard’s analytical powers.’ – Steinitz.) 15…Qe6 16 Re1 Qxe1 17 Qa4+ Kd8 18 Qa5+ Ke8 19 Qb5+ Ke7 20 Qc5+ Kf6 21 Qg5+ Ke6 22 Qd5+ Resigns.

(Kingpin, 1998)

For an illustration of the widely-acknowledged form of the ‘epaulette mate’ we turn to a game from page 382 of the 15 December 1890 issue of La Stratégie:

Jackson Whipps Showalter – Logan

Correspondence game

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O d6 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Na5 10 Bg5 f6 11 Bxg8 Rxg8 12 Bh4 Bg4 13 e5 dxe5h 14 Re1 Bxf3 15 Qxf3 Qxd4 16 Re4 Qd7 17 Rd1 Qf7 18 Qg4 h5 19 Qf5 Nc4 20 Rxc4 Qxc4 21 Nd5 Qc5 22 Qe6+ Kf8 23 Bxf6 Re8

White announced mate in seven moves: 24 Ne7 Qxf2+ 25 Kh1 Qxf6 26 Ng6+ Qxg6 27 Rf1+ Bf2 28 Rxf2+ Qf6 29 Rxf6+ gxf6 30 Qxf6.

(2694)

See also Jackson Whipps Showalter.

J.L. Younkman – E.A. Coleman

Correspondence game (Western Australia), 1915

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 5 O-O d6 6 d4 h6 7 c3 Qe7 8 Na3 a6 9 Nc2 Be6 10 Bd3 Nf6 11 b3 Nbd7 12 h3 Nh5 13 Re1 O-O 14 Ba3 c5 15 Qd2 g4 16 hxg4 Bxg4 17 Qf2 Bf6 18 Rad1 Rfe8 19 b4 cxd4 20 cxd4 b5 21 Bb2 Ng3 22 Ra1 Bxf3 23 Qxf3 Bg5 24 a4 bxa4 25 Rxa4 Nf6 26 e5 h5 27 Ne3 Qd7 28 Ra5 dxe5 29 Nc4 Ng4 30 Nb6 Qe7 31 Nxa8 Bh6 32 Raxe5 Qh4 33 Rxe8+ Bf8

34 Qxg4+ hxg4 35 Nc7 Qf6 36 Rxf8+ Kxf8 37 Re8+ Kg7 38 Re6 Qh4 39 d5+ f6 40 Bxf6+ Qxf6 41 Ne8+ Resigns.

Source: BCM, September 1915, pages 323-324.

(2744)

Which is the earliest surviving correspondence game played in the United States? According to page 37 of volume one of Carlo Alberto Pagni’s book Correspondence Chess Matches Between Clubs 1823-1899, the distinction belongs to an encounter played from 1840 to 1842 between Norfolk, Virginia and New York. However, we note the following game (‘hitherto unpublished’) on pages 271-272 of Chess for Winter Evenings by H.R. Agnel (New York, 1848):

Washington Chess Club – New York Chess Club

Correspondence, 1839

Scotch Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Qf6 5 O-O d6 6 c3 d3 7 Ng5 Ne5 8 Bb5+ c6 9 f4 Ng4 10 Bc4 N4h6 11 e5 Qd8 12 Bxd3 dxe5 13 fxe5 Be7 14 Ne4 Ng4 15 Bf4 h5 16 Qf3 Qb6+ 17 Kh1 Be6 18 Nbd2 O-O-O 19 Nc4 Bxc4 20 Bxc4 N8h6 21 Bxh6 Nxh6 22 Bxf7 h4 23 b4 g5 24 Be6+ Kb8 25 Nf6 Ka8 26 a4 Rd2 27 a5 Qb5 28 Qe3 Re2 29 Qxg5 Qxe5 30 Qg7

30…Rg8 31 Qxe7 and Black mated in four moves.

An account (though not the moves) of an 1835 game between Washington and New York was given on pages 402-403 of Fiske’s volume on the New York, 1857 tournament (as well as on page 29 of the above-mentioned Pagni book). Were there indeed two games, one in 1835 and the other in 1839, or has the above game simply been misdated in one of the sources?

(2792)

From John Hilbert (Kenmore, NY, USA):

‘I don’t know about any 1835 game, but there were in fact two games between New York and Washington played in 1838-39. The first part of each was given in the United States Magazine & Democratic Review, Volume 5, Issue 13 (January 1839), page 96. In the case of the first game, the moves played up to that point were:

New York Chess Club – Washington Chess Club

Correspondence, 1838-39

Bishop’s Opening1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Bc5 3 c3 Qe7 4 Nf3 d6 5 d3 Nf6 6 Qe2 Be6 7 Bb3 Nbd7 8 Bg5 h6 9 Bh4 Bxb3 10 axb3 Qe6 11 Nbd2 Nh5 12 Bg3 Nxg3 13 fxg3 a6 14 Nh4 g6 15 b4 Ba7 16 Qf3 c6 17 Rf1 O-O 18 g4 d5 19 h3 Qe7 20 g3 Rad8 21 Kd1 Nb6 22 Kc2 Rd7 23 Nb3 Rfd8 24 Nc5 Rd6 25 b3 dxe4.

The following is the United States Magazine & Democratic Review’s report:

“Match of Chess Between New York and Washington – It is generally known to the votaries of this noble game in this country – if no higher name will be permitted by those unacquainted with its merits, and judging it only by its apparent result – that a public Match by correspondence has for some time been in progress between the rival Chess clubs of New York and Washington, the commercial and political capitals of the Union. As we have been several times requested to makes its progress known to those of our readers interested in the subject, it may find a not inappropriate place on this page. The match was commenced in January 1838 – the challenge proceeding from New York. Two games are played simultaneously, each party having the first move in one game. The stake is a small amount, to be appropriated to the purchase of some suitable trophy of victory. The time allowed for each move is one week. One of the games was at one period interrupted for a few moves, by a claim by the New York club to a default, presumed to have been incurred by the other party by a failure to move within the allotted term. The claim was disputed, and is still in suspense, the game having been resumed and continued as a ‘back game’, in case of the claim being eventually sustained. Of the merits of the respective play, and the probable issue of the match, every reader may judge for himself.”

The publication then gave the second game (i.e. the one presented in C.N. 2792) as far as 22 Bxf7.’

(2795)

Roald Berthelsen (Täby, Sweden) writes:

‘As reported on page 54 of the book Dansk korrespondanceskak by Villads Junker (published in Aabybro in the mid-1940s), in the Danish over-the-board championship in Svendborg in 1930 A. Desler and N. Lie finished equal second. The organizers decided to break the tie with two games of correspondence chess (a contest which N. Lie won 1½-½). Has any similar arrangement occurred in other over-the-board tournaments, past or present?’

(3199)

A further illustration of the ‘once’ school of narrative comes from page 24 of Curious Chess Facts by I. Chernev (New York, 1937):

‘Steinitz was once arrested as a spy. Police authorities assumed that the moves made by Steinitz in playing his correspondence games with Chigorin were part of a code by means of which important war secrets could be communicated.’

The identical paragraph appeared on page 31 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), whereas on page 89 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949) the wording was slightly different:

‘Steinitz was once misjudged to be a spy. Police authorities assumed that the moves made by him in playing his correspondence games with Chigorin were part of a code by means of which important war secrets could be transmitted.’

We have yet to find any such incident mentioned in contemporary reports on the two-game cable match in 1890-91 between Steinitz and Chigorin, about which, incidentally, the then world champion wrote on page 107 of the April 1891 International Chess Magazine:

‘Never before in the history of our pastime has a chess contest created such widespread and literally universal interest during its progress as the one just concluded between myself and Mr Chigorin.’

We would, though, draw attention to the following passage by Walter Penn Shipley in the Philadelphia Inquirer, as quoted on page 62 of the American Chess Bulletin, March 1918:

‘We note in the daily papers a curious break in the affairs of Lorenz Hansen, a Dane, but who has been in this country for many years and is a naturalized citizen. Lorenz Hansen has been for many years an enthusiastic chessplayer and an able problem composer. We have published many of his problems in this column, and some of exceptional merit. Lorenz Hansen was recently arrested on a technical charge, the Federal authorities believing that he had a secret code and was communicating with someone at Grand Rapids, Mich. On further examination the secret code appears merely to have been a harmless correspondence game of chess, the moves, as usual, being sent by postal card. It is unnecessary to state that when the true state of affairs became known Mr Hansen was promptly released.

This adventure recalls one of the late William Steinitz. When he played his second match with Lasker at St Petersburg, before leaving this country Steinitz arranged an elaborate code whereby at slight expense he could cable the moves in his match to a syndicate of New York newspapers. Steinitz received a liberal compensation for his work. The old man had spent a great deal of time on perfecting his code, but unfortunately on arriving in St Petersburg the authorities promptly confiscated the code, stating that it was impossible to believe that it was merely for the purpose of cabling chess moves and in reality was to give secret information to parties in America. Being thus deprived of his code, he was unable to cable the moves of his match, and thereby lost the fruit of many months’ hard labor. At the termination of the match the code was returned to Steinitz by the Russian authorities, stating they had found it to be as represented, but then, of course, it was too late to be of any use to the world’s master. Steinitz’ breakdown was unquestionably partially due to his great disappointment in this matter.’

What truth there is in any of the above we have no idea, and for now we merely point out that the second match between Steinitz and Lasker was held in Moscow, not St Petersburg.

(3345)

A paragraph from page 468 of the December 1896 BCM:

‘The long-expected return match between Messrs Lasker and Steinitz, for the championship of the world, began at Moscow, on 7 November, having been delayed a few days owing to a political difficulty. Mr Steinitz had arranged to telegraph the games to America in cypher, which cryptogram, however, had to be submitted first to the censorship of the Russian government, and it took some time to convince the authorities that there was nothing nihilistic in the mysterious messages to be sent.’

(6699)

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes a news report on page 6 of the New York Sun, 20 November 1890 and, in particular, the final paragraph:

‘We imagine that the popular estimate of chess will be revolutionized by these games. As their slow changes are watched by a continually increasing attention on the part of the public, the idea must grow that chess under the ordinary rules is too fast, and that a truly perfect contest must spread over weeks or even months, perhaps years.’

(7851)

‘There never was a game so short but so extraordinary in combinational content. Arthur Feuerstein, an exceptionally talented master, gives us this gem.’ So wrote William Lombardy when introducing the following game on pages 273-274 of Modern Chess Opening Traps (New York, 1972):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 c6 3 d5 cxd5 4 cxd5 g6 5 Nc3 Qa5 6 g3 Ne4 7 Qd4 Nxc3 8 Bd2 Qxd5 9 Qxc3 Nc6 10 Qxh8 Nd4 11 Rc1 Qxh1 12 Qxd4 Qxg1 13 Qxa7 Resigns.

No details of the occasion of the game were supplied by Lombardy, but we note that on page 381 of the December 1955 Chess Review John W. Collins’ ‘Postal Games’ column presented it as having been played by A. Feuerstein and J.E. Bennett. It also appeared on page 103 of Modern Chess Miniatures by L. Barden and W. Heidenfeld (London, 1960), as ‘Feuerstein-Bennett, New York, 1955’.

However, a number of databases give it as a 1954 correspondence game in England between Peter James Oakley and W. Nash.

Error or coincidence?

(3401)

Aben Rudy (Scottsdale, AZ, USA) has brought C.N. 3401 to the attention of Arthur Feuerstein, a lifelong friend. Mr Feuerstein recalls winning the 1955 postal game against Bennett and comments:

‘This was probably my first “brilliancy”. How odd that the identical game was played in 1954. I certainly had no knowledge of it at the time.’

(3404)

Morgan Daniels (London) mentions that a frequent entry in old editions of the Guinness Book of Records concerned a chess game, begun in the 1920s and continued for decades, in which the players, Grant and MacLennan, played a move each Christmas.

We are not aware that the game-score has ever been published, but perhaps a reader will be able to provide information. In the meantime, we note two other cases of lengthy postal games:

Firstly, a paragraph from page 215 of CHESS, 17 May 1957:

‘H. Jarvis, Croydon, played postal chess from 1931 (when he went on holiday to Germany) onwards, with Eberhardt Wilhelm, secretary of the international correspondence chess organization. When the war started, it was Mr Jarvis to move. Naturally the game was abruptly interrupted, and after the war ended it was two years before normal postal services were resumed. Wilhelm thereupon wrote and pointed out that it had been Mr Jarvis’ move for eight years and said that if he did not reply by return he would claim the game. Mr Jarvis had the move ready; he despatched a move at once and the games were duly concluded. So the one move took eight years. “Is this a record” asks Mr Jarvis “for the longest time ever taken to play a chess move?”’

Secondly, a game which took about 16 years and was widely published in the mid-1870s:

Karl Brenzinger – Francis Eugene Brenzinger

Correspondence, 1859-18 March 1875

Two Knights’ Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Na5 6 Qe2 Nxc4 7 Qxc4 Bd6 8 d3 O-O 9 Nc3 h6 10 Nge4 Kh8 11 O-O Nh5 12 d4 f5 13 Nxd6 cxd6 14 dxe5 dxe5 15 Qe2 Qe8 16 Nb5 f4 17 f3 Ng3 18 hxg3 fxg3 19 f4 Bd7 20 Nd6 Qe7 21 Ne4 Qh4 22 Nxg3 Qxg3 23 Rf3 Bg4 24 Rxg3 Bxe2 25 Re3 Bc4 26 d6 Rxf4 27 Re1 Rd4 28 b3 Bb5 29 c4 Bc6 30 c5 Rg4 31 Re2 Rf8 32 Be3 Kg8 33 a4 Rb4 34 Rb2 Kf7 35 Bd2 Rg4 36 Bc3 Ke6 37 b4 Rf3

38 Bxe5 Kxe5 39 b5 Be4 40 Rd2 Rfg3 41 Raa2 Bxg2 42 d7 Bc6+ 43 Kh2 Bxd7 44 Rxd7 Rg6 45 Re2+ Kf6 46 Rde7 (This mistake was attributed to impatience after Black took seven months over his 45th move.) 46...Rg2+ 47 Rxg2 Rxg2+ 48 Kxg2 Kxe7 49 Kf3 h5 50 a5 Kd7 51 White resigns.

Sources: La Stratégie, 15 May 1875, pages 141-143, and Deutsche Schachzeitung, July 1875, pages 218-219.

Although the magazines specified that White and Black lived in Pforzheim and New York respectively, Irving Chernev (on page 129 of his book Wonders and Curiosities of Chess) stated that the game was ‘between a Mr Brenzinger of New York and his brother in England’.

(3435)

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) sends Steinitz’s notes to the game in C.N. 3435, from The Field, 24 April 1875:

‘Dr Brenzinger – F. Eugene Brenzinger

Correspondence game, 1875We derive from the Turf, Field, and Farm, of New York, the moves of the ensuing game, which was played by correspondence between Dr Karl Brenzinger, of Pforzheim, Baden, and Mr F.E. Brenzinger, of New York. It is probably the longest game, in point of time taken for its progress, that has ever been played; for, according to the statement of the above quoted paper, it was commenced as far back as 1859, and was only brought to a conclusion on 18 March 1875, its duration having extended over 16 years. 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Na5 6 Qe2 (An unusual continuation, and no better for its originality. Black can now recover the pawn, with at least an even game. Mr Zukertort recommends here 6 Bb5+, as even sounder than Morphy’s favorite move, 6 d3.) 6...Nxc4 7 Qxc4 Bd6 (Black’s refusal to recover the pawn cannot be regarded as safe, though it leads to lively and interesting complications. We believe his surest plan to have been to capture the d-pawn with the queen, followed by ...Bd6, in case the queen took the c-pawn, and, if White exchanged queens at once, his knight would have been out of play.) 8 d3 O-O 9 Nc3 h6 10 Nge4 Kh8 11 O-O Nh5 12 d4 f5 13 Nxd6 cxd6 14 dxe5 dxe5 15 Qe2 Qe8 16 Nb5 f4 (A very fine conception, which frustrates White’s contemplated attack.) 17 f3 (Best. Black’s answer to 17 Nc7 would have been ...Qg6, threatening the destructive assault of ...f3, and the game might have gone thus: 17 Nc7 Qg6 18 Qxe5 Bh3 19 g3 Rae8 20 Nxe8 Rxe8 21 Qc3 Qe4 22 f3 Qe2 and wins.) 17...Ng3 (A bold measure, which it was rather difficult to counteract; but we think that, with the best play, the opponent ought to have been able to turn the game in his favour.) 18 hxg3 fxg3 19 f4 (The only move. 19 Be3 would have been of no use, e.g.: 19 Be3 Qh5 20 Rfe1 Bg4 21 queen moves Qh2+ 22 Kf1 Bxf3 and must win.) 19...Bd7 20 Nd6 (This manoeuvre was by no means a bad recourse, and was evidently adopted with the intention of returning the piece gained for the troublesome pawn at g3, and afterwards relying upon the numerical superiority of pawns. But it strikes us that the success of this plan, though it secured a draw, was made very doubtful, as far as winning was concerned, by the circumstance of the bishops being of opposite colour; while another modus operandi might, in our opinion, also have provided for Black an escape from the dilemma, and, at the same time, retained for him a much better chance of ultimate victory. Of course, Nc7 would have still been bad, on account of Black’s reply, ...Qg6, and also to win the knight by ...Qb6+; but, supposing White retreated the knight to c3, we see no stronger continuation for Black than the following: 20 Nc3 Qg6 21 f5 Bxf5 [has he anything better?] 22 Qe3, followed by Ne2, and we believe that Black has not sufficient for the piece sacrificed.) 20...Qe7 21 Ne4 Qh4 22 Nxg3 Qxg3 23 Rf3 Bg4 24 Rxg3 Bxe2 25.Re3 (25 fxe5 appears more plausible; though against the best play it would have scarcely effected more than a draw; for instance: 25...Rf1+ 26 Kh2 Bc4 27 d6 Be6 28 b3 Rc8 29 c4 b5, etc.) 25...Bc4 26 d6 Rxf4 27 Re1 Rd4 28 b3 Bb5 29 c4 Bc6 30 c5 Rg4 31 Re2 Rf8 32 Be3 Kg8 33 a4 Rb4 34 Rb2 Kf7 (All this is nicely played by Black.) 35 Bd2 Rg4 36 Bc3 Ke6 37 b4 Rf3 38 Bxe5 (Had White protected the bishop by Rc2, the game might have proceeded thus: 38 Rc2 Be4 39 Rd2 Rxc3 40 d7 Rxg2+ 41 Rxg2 Kxd7, etc.) 38...Kxe5 39 b5 Be4 40 Rd2 Rfg3 41 Raa2 Bxg2 42 d7 (Our American contemporary here justly remarks that White could have easily drawn the game by now exchanging all the pieces, followed by a5, but that Dr Brenzinger probably, and not without reason, played to win.) 42...Bc6+ 43 Kh2 Bxd7 44 Rxd7 Rg6 45 Re2+ Kf6 46 Rde7 (A gross blunder, which makes the termination quite unworthy of the longest-lasting game on record. Our American contemporary ascribes this sudden collapse to a feeling of impatience on the part of Dr Brenzinger, caused by his opponent having taken seven months before answering the last move.) 46...Rg2+ 47 Rxg2 Rxg2+ 48 Kxg2 Kxe7 49 Kf3 h5 50 a5 Kd7 51 White resigns.’

(3438)

Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) quotes the following from Turf, Field and Farm, 4 June 1875:

‘We are indebted to Mr F.E. Brenzinger, of New York, for the subjoined game, together with the accompanying particulars of the match just concluded between that gentleman and his brother, Dr Karl Brenzinger, of Pforzheim, Baden.

Mr B. writes us as follows:

“I send you the last of five games played, by correspondence, between Dr Karl Brenzinger, of Pforzheim, Baden, and his brother F.E. Brenzinger, of New York. The games were begun in 1859, and the opening moves were published at that time by Mr Samuel Loyd in the New York Illustrated News, and also in the Musical World. Mr Loyd predicted that the match would probably be finished about the year 1870.

The first game was won in March 1866, by Dr B., only 24 moves having been made on each side; the second, which resulted in a mate on the 45th [sic] move, was also scored by the Doctor, in December 1869.

Mr F.E. B. won the third in April 1871, and also the fourth (which was published a few weeks ago) in March 1875.

The fifth and last was declared a draw in May 1875, thus leaving the score: Dr B. 2; Mr B. 2; Drawn 1.

In 1863 a contest of a similar character was commenced between Mr Albert Hug, of Mannheim, Baden, and Mr F.E. Brenzinger, of New York.

Five games were to be played, three of which are already finished (Mr B. 2, Mr H. 1), while two are still pending.”’

The same column gave this game-score:

Francis Eugene Brenzinger – Karl Brenzinger1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 f4 Bc5 5 Nf3 Ng4 6 Bxf7+ Kf8 7 Rf1

7...Nxh2 8 Qe2 Nxf1 9 Qxf1 Qf6 10 Bb3 Nd4 11 d3 Nxf3+ 12 Qxf3 Bb4 13 Bd2 Bxc3 14 bxc3 exf4 15 Bxf4 d6 16 Kd2 Ke7 17 e5 dxe5 18 Re1 Rf8 19 g3 Kd8 20 Qd5+ Qd6 21 Bg5+ Kd7 22 Qh1 h6 23 Be3 Kd8 24 Qe4 c6 25 Qa4 c5 26 Qe4 Kc7 27 Bd5 Bf5 28 Qc4 Rfd8 29 Bf3 Be6 30 Qe4 Bd5 31 Qxd5 Qxd5 32 Bxd5 Rxd5 33 c4 Rd6 34 Bxc5 Re6 35 d4 g6 36 d5 Ree8 37 Rf1 b6 38 Rf7+ Kd8

39 Rxa7 Rxa7 40 Bxb6+ Ke7 41 Bxa7 Rc8 42 c5 Ra8 43 Bb6 Rxa2 44 Kd3 Ra3+ 45 Ke4 Rxg3 46 Kxe5 Rg5+ 47 Kd4 Rg1 48 c4 Rb1 49 Bc7 h5 50 c6 h4 51 Bf4 Rd1+ 52 Kc5 h3 53 d6+ Kd8 54 d7 Rg1 55 Bd2 Rd1 Drawn.

Our correspondent notes that this game apparently lasted longer than the one given in C.N. 3435 (which finished in March 1875). He adds that the second game was published in the Spirit of the Times, 25 December 1869:

Karl Brenzinger – Francis Eugene Brenzinger

Second match game, correspondence, 1859 – December 1869

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 O-O d6 7 d4 exd4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Bb2 Na5 10 e5 Nxc4 11 Qa4+ c6 12 Qxc4 d5 13 Qd3 Ne7 14 Nc3 Bf5 15 Qe3 h6 16 Nh4 O-O 17 Ne2 Be6 18 Ba3 Re8 19 f4 Nf5 20 Nxf5 Bxf5 21 h3 Re6 22 Ng3 Be4 23 Bd6

23...Bxg2 24 Kxg2 Qxd6 25 f5 Ree8 26 f6 g5 27 Rf5 Kh8

28 Rxg5 Qxf6 29 Rh5 Kh7 30 Rf1 Qg6 31 Rxf7+ Kg8 32 Rf4 Kh7 33 Rxh6+ Kxh6 and White mates in five moves.

(5683)

John Blackstone mentions that several online databases contain correspondence games attributed to Mikhail Tal and asks which world champions have played postal chess.

At this stage we should like to build up a list of authenticated correspondence games played by the world champions of the post-Second World War era. Their predecessors’ exploits in this field are already relatively well documented.

(3719)

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) notes that pages 29-30 of The Unknown Bobby Fischer by John Donaldson and Eric Tangborn (Seattle, 1999) gave a 12-move loss by Fischer in 1955 against A.W. Conger. The game being well known today, we refrain from going into the details here.

(6283)

Noting that Aron Nimzowitsch included in his books a few of his correspondence games, Javier Asturiano Molina asks how many games the master is known to have played by post.

Readers’ assistance will, as ever, be welcome. To make a start, we note that Nimzowitsch gave victories over G. Fluss in both My System (game dated 1913) and The Praxis of My System (game dated 1912-13), while the latter book also had a 1924-25 game against O.H. Krause. On pages 429-430 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 October 1925 Nimzowitsch presented the first 18 moves of a correspondence game he was playing against V. Edman. A postal game lost by Nimzowitsch to K. Bētiņš in a match dated 1911-13 was published on pages 55-56 of the March 1965 Chess Life.

(4671)

‘A thousand threepenny stamps were stolen from a North Wales Post Office recently. The police are looking for anyone starting a correspondence game.’

D.J. Morgan, October 1972 BCM, page 400.

C.N. 1792 cited from page 3 of the Winter 1988 issue of Chess Post a neat message for use in correspondence chess:

‘If resigns, thank you for the game.’

In C.N. 2426 the late David Pritchard referred to a postcard on which a player wrote his latest move and added:

‘If Rd7, resigns.’

On the broader topic of correspondence chess, we have before us a passage by C.H.O’D. Alexander from his Sunday Times column on page 82 of the Supplement, 8 April 1973:

‘Punch-drunk at the moment from struggling with my games in the World Team Final I am incapable of annotating anyone else’s games; here, therefore, is one of my own [against Ulyanov] from a Cheltenham v Sochi friendly match. Friendly – yes I suppose so; but not conducted in any spirit of levity or undue haste. One of our team went round the world by sea in the middle and only got two moves behind the rest of us; and while I won this game in the comparatively short time of 2½ years, in my other game against Ulyanov I have been on the defensive for four years – I hope to equalize any year now.’

(5249)

Vladimir Neistadt asks to see the game published by Alexander, and requests any further information about the match between Cheltenham and Sochi (the places were twinned), such as the other participants’ names.

Below is the score of the Alexander v Ulyanov game published, with notes, in the Sunday Times, and dated 1968-70:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bc4 e6 7 Bb3 Be7 8 f4 O-O 9 f5 e5 10 Nde2 Nc6 11 Be3 b5 12 Nd5 Nxe4 13 O-O Rb8 14 c3 Bg5 15 Qd3 Nc5 16 Bxc5 dxc5

17 f6 c4 18 Qg3 h6 19 Rad1 cxb3 20 h4 Kh7 21 fxg7 Kxg7 22 Rf6 bxa2 23 hxg5 Qxd5 24 Rxd5 a1(Q)+ 25 Rf1 Qxf1+ 26 Kxf1 h5 27 Rd6 Resigns.

Alexander also discussed the match on page 98 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973), published shortly before his death:

Acknowledgement: Cleveland Public Library

In the introduction to the 8 April 1973 Sunday Times column, Alexander gave some general observations on postal play:

‘Though much correspondence play, even at international level, is surprisingly bad, playing C.C. makes one realize that chess is difficult; I can take as much time as I like and still get it wrong. Apart from oversights (you make those after two hours’ thought as well as after two minutes’) there are three causes of failure. First, inadequate opening knowledge; how many innocents come to grief through trustingly following MCO on the assumption that it must be right. Next lack of imagination – you simply fail to see a possible line. Most important, faulty judgement; one weighs up positions wrongly.’

(12068)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) writes:

‘On page 272 of the 25 October 1851 issue of Home Circle, a woman corresponding under the name of “Sybil” issued a challenge to “any chessplayer … not much above the average …” to play a game by correspondence which would be printed as it progressed in the chess column of Home Circle. The 6 December 1851 issue (page 368) reported that she had received several acceptances and had picked one name from an urn: G.B. Fraser of Dundee, who became one of the best players in Scotland in the 1860s and 1870s. Week by week over the next 15 months the moves of the game were reported until at move 51 “The ‘fayre Sybil’ mates with the queen” (Home Circle, 5 March 1853, page 160). The entire game was published with commentary on page 192 of the 19 March 1853 edition and was also reprinted as a game between “A Lady” and “Mr F.” on pages 232-233 of the March 1853 issue of the Chess Player.’

‘A Lady’ – George Brunton Fraser

Correspondence, 1851-53

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb6 7 Bg5 d6 8 h3 h6 9 Bxf6 Qxf6 10 Bb5 O-O 11 Bxc6 bxc6 12 Nc3 Qg6 13 Nh4 Qg5 14 g3 f5 15 Nf3 Qg6 16 Nh4 Qf6 17 e5 dxe5 18 dxe5 Qxe5+ 19 Qe2 Qc5 20 O-O f4 21 g4 Bd7 22 Rad1 Rae8 23 Ne4 Qb4 24 Rfe1 Ba5 25 a3 Qb3 26 Rd3 Qf7 27 b4 Bb6 28 Rf3 Be6 29 Qc2 Bd5 30 Nf5

30...Be3 31 Rexe3 fxe3 32 Rxe3 Kh8 33 f3 Qd7 34 Nc5 Qd8 35 Rxe8 Qxe8 36 Kg2 Qe1 37 Nd3 Qe8 38 Nf4 Qf7 39 Ne7 Qxf4 40 Ng6+ Kg8 41 Nxf4 Rxf4 42 Kh2 Rxf3 43 Qa4 Kh7 44 Qxa7 h5 45 gxh5 Kh6 46 a4 Rf7 47 a5 Kg5 48 Qc5 Kxh5 49 a6 Rf1 50 Qe7 g5 51 Qh7 mate.

(5918)

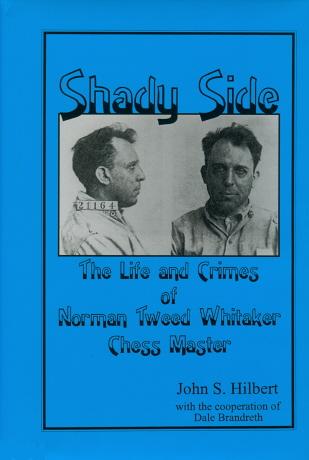

Knud Lysdal (Grindsted, Denmark) asks whether further details are available about an episode reported by James E. Gates in his obituary of Norman T. Whitaker on page 521 of the August 1975 Chess Life & Review:

‘One of the stories about him concerned a US correspondence championship before World War II. A friend of his, who was competing in the tournament, suddenly died. His widow needed money, and this gave Norman the idea of finishing his friend’s games without letting anyone know. Whitaker wound up winning the tournament – the first, as far as I know, won by a dead man.’

Gates’ story was quoted on page 145 of Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 2000).

We mentioned Dr Hilbert’s deeply-researched book in C.N. 2443, describing it as ‘an enthralling romp through tournament halls, court rooms and prison cells’.

(6318)

Pages 16-23 of volume three of Klassische Schachpartien by E. Bogoljubow (Berlin and Leipzig, 1928) had a section on correspondence chess. He reported that between October 1920 and August 1921 he played 25 games against Swedish players and clubs, scoring +19 –1 =5. Below is the first of the five games (one of two between the same parties) which Bogoljubow annotated. His punctuation is provided here for general guidance:

Eskilstuna Club (W. Lundmark) – Efim Bogoljubow

Correspondence, 1920-21

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 Nc6 3 Nf3 e6 4 Qe2 Be7 5 Nc3 a6 6 a4 Nb4 7 d3 d5 8 Bb3 Nf6 9 Bd2 dxe4 10 Nxe4 Nbd5 11 Ne5! O-O 12 O-O Qc7 13 f4 b6 14 Rae1 Bb7 15 c3 Rad8 16 Ng5! h6

17 Rf3!! b5 18 Rh3 c4! 19 dxc4 Qb6+ 20 Kh1 bxc4 21 Bxc4 Qxb2 22 Ngxf7 Rxf7 23 Nxf7 Kxf7 24 Qxe6+ Kf8 25 Rd3! Bc8 26 Qe5! Qb7 27 f5 Ng4! 28 Qg3 h5!! 29 h3 Ngf6 30 Qg6 Qc7 Drawn.

Bogoljubow’s concluding comment was:

‘One of the most difficult correspondence games that I have ever played.’

This portrait was the frontispiece to volume one of Klassische Schachpartien (Berlin and Leipzig, 1926):

(6588)

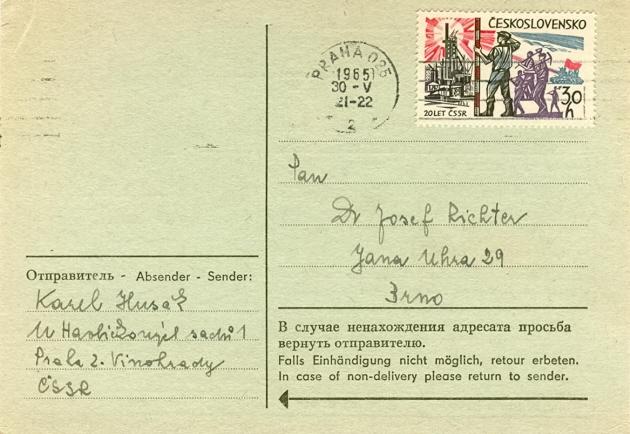

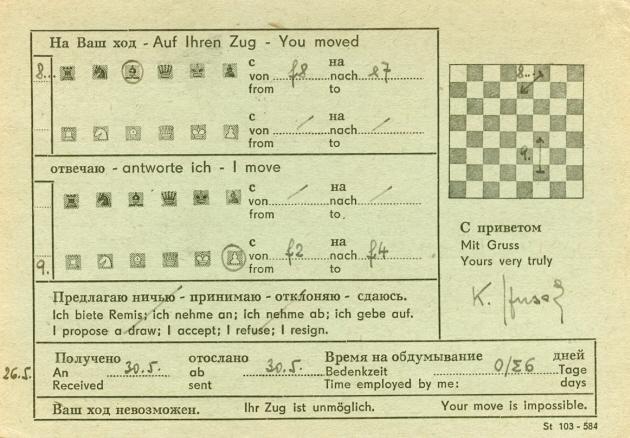

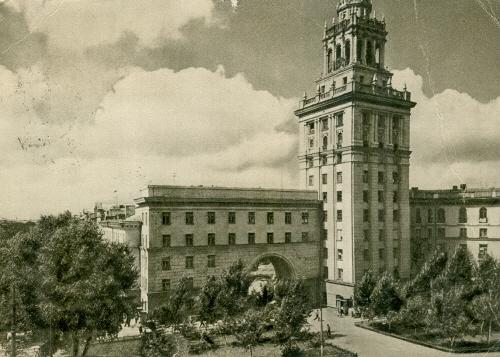

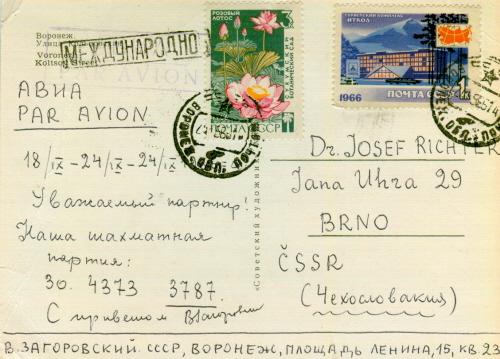

A postcard in our collection sent by Karel Husák to Josef Richter:

(7365)

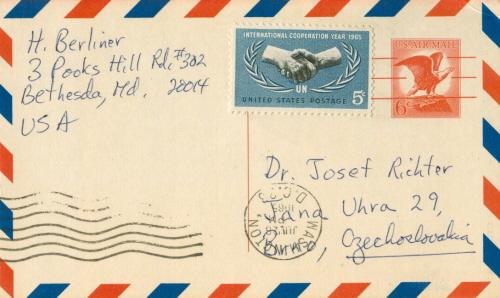

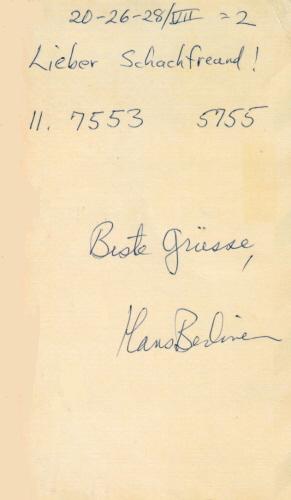

The postcard shown in the previous item concerned a game played in the Fifth World Correspondence Championship (1965-68), which was won by Hans Berliner. From the same event, here are two more cards sent to Josef Richter:

Zagorovsky plays 30...Rc7-h7.

Berliner plays 11...e7-e5.

(7566)

Hans Berliner (1929-2017):

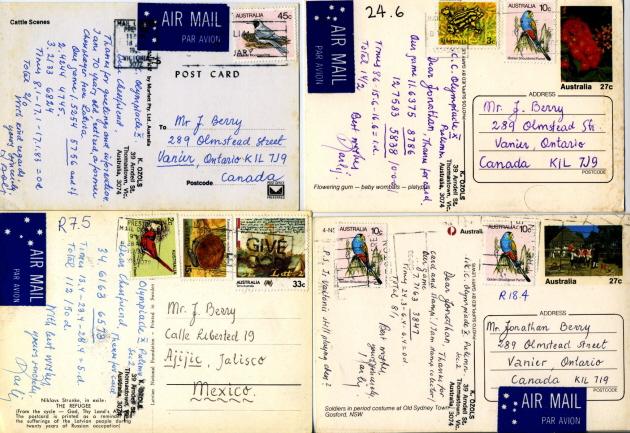

Jonathan Berry (Nanaimo, BC, Canada) has also forwarded us a number of postcards from a game which he played against Karlis Ozols in the tenth Correspondence Chess Olympiad (1983-84):

(7581)

This article by G.H. Diggle was published in Newsflash, August 1976 and on page 14 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘The Badmaster’s first ever Correspondence Game, played for a Minor County at the age of 17, was a “horrific experience”. With fluttering heart he opened the “official envelope” containing the name and address of a far distant and mysterious opponent, and he eagerly devoured the accompanying “Rules and Regulations” at least two dozen times over. “A player” (to quote the Act) was entitled to consult chess works, but to receive “no other assistance whatsoever”. The BM proudly resolved that (whatever others got up to) his genius should never be contaminated by outside advice. But alas, it soon was, and “the wages of sin was resignation” (on the 30th move).

In fairness to the BM it must be pointed out that he was then by some 20 years the youngest member of a provincial club, that in those glorious days (would they were with us again!) young players stood in awe of old ones (who patronized and bullied them dreadfully), and that the BM was constantly tempted by spurious local grandmasters and false “Medicine Men” who would “wait for his unguarded hours” and demand to be shown his position. The worst of them was a local shopkeeper (and lay preacher) whose recreations were chess and hypocrisy. He was one of those men who could see right through a position before you had even set it all up. “I was thinking of going there ...”, faltered the BM timidly. “Rubbish, young man, rubbish!”, roared “Nestor”. “Here’s your move, boy, here! Sews him up completely!” “So you think that ...” “Suttonly, suttonly”, he burst forth aggressively, “Why, you must win a piece in two moves – you can’t help but win a piece in two moves! Oh, bless your life, etc. etc.” The BM, after suffering pangs of conscience (but not daring to send his own move as he knew it would all come out at the next inquisition), dispatched the one prescribed by “higher authority”. A few days afterwards he visited the sage’s shop and complained that he had not won a piece in two moves after all. “Haven’t you really, now?”, rejoined that worthy in a tone of polite commiseration (as though he had never had anything to do with it at all). “But”, hinted the BM delicately, “I thought I was bound to win a piece in two moves.” “Now, now, Mr Bad”, replied the unabashed mentor, “When you have played chess for a few more years (here his manner became most impressively and portentously solemn) you’ll discover that in chess, as in everything else, the Mills of God grind slowly!” This homily he wound up with a great asthmatical sigh – and the BM could only steal from his presence on tiptoe, leaving him to finish his sublime train of thought in seclusion, and feeling utterly ashamed of ever having doubted the wisdom of such a man.’

(7551)

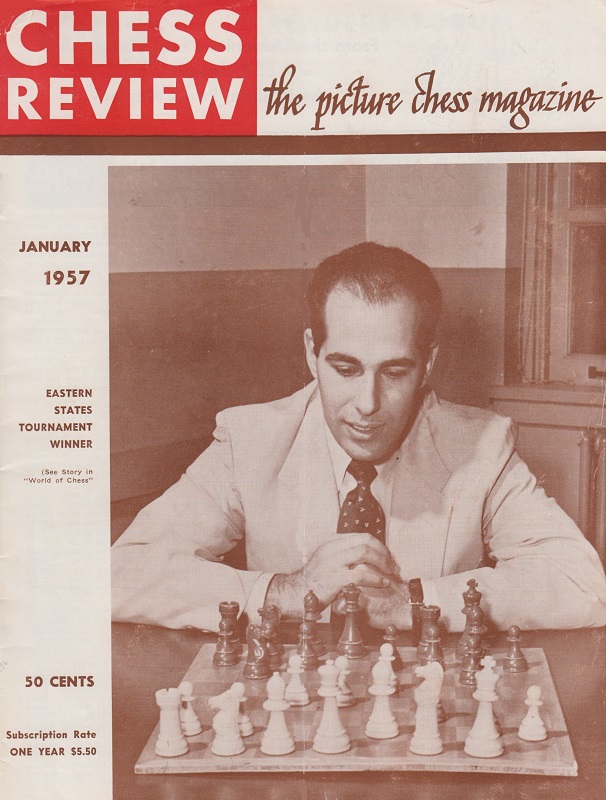

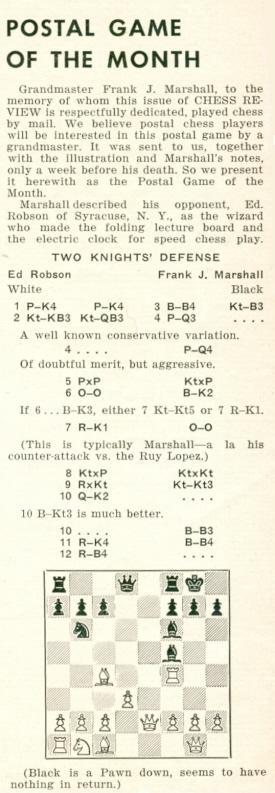

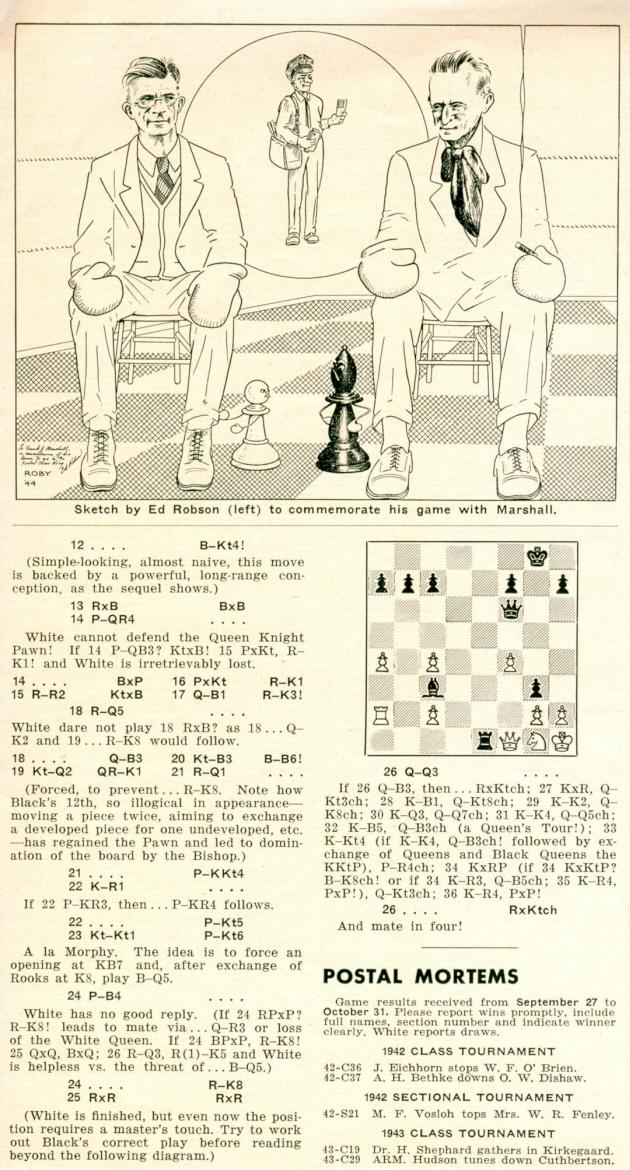

The last game in Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994) – see pages 361-362 – was played by correspondence against Ed Robson and is said to have ended ‘21 Rd1 g5! White resigns’. However, the following was published in the Marshall memorial issue of Chess Review (December 1944, pages 28-29):

(7374)

In the nineteenth century, games were seldom annotated at length, but an exception occurred in 1853, in the opening number of the British Chess Review: pages 22-28 discussed a correspondence game between Amsterdam and London, with notes by Greenaway and Medley.

Amsterdam – London

Correspondence, July 1851-November 1852

Scotch Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Bc5 5 c3 Nf6 6 e5 d5 7 Bb5 Ne4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Bxc6+ bxc6 10 Nc3 f5 11 h4 O-O 12 Bf4 c5 13 Kf1 Rb8 14 Na4 cxd4 15 Nxd4 Qe8 16 b3 c5 17 Nc2 d4 18 Rc1 Ba6+ 19 Kg1 Bb5 20 Na3 Bxa4 21 bxa4 Bc7 22 f3 Nc3 23 Qc2 Bxe5 24 Re1

24...Bxf4 25 Rxe8 Rfxe8 26 Kf2 Re2+ 27 Qxe2 Nxe2 28 Kxe2 Re8+ 29 Kf2 d3 30 Rd1 d2 31 Kf1 Bg3 32 Nc2 Re1+ 33 Rxe1 dxe1(Q)+ 34 Nxe1 Bxe1 35 Kxe1 Kf7 36 White resigns.

Page 28 of the British Chess Review commented that it was ‘perhaps the most brilliant game on record, ever played by correspondence’. In contrast, when the magazine’s editor, Daniel Harrwitz, gave the game on page 133 of his Lehrbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1862) there was a single two-word note – ‘nicht gut’ – to a move (9 Bxc6+) which had received no comment in the British Chess Review.

See too pages 49-51 of volume one of Correspondence Chess Matches Between Clubs 1823-1899 by Carlo Alberto Pagni (Turin, 1994) and pages 44-46 of Correspondence Chess in Britain and Ireland, 1824-1987 by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2011).

(7426)

From page 23 of Keres’ Best Games 1932-1936 by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1937):

‘It has often been observed that certain players are far better at correspondence play than at over-the-board play. A very good example is the Italian player Stalda, who is probably one of the strongest correspondence players in the world, although he has never distinguished himself in a regular tournament.’

(7789)

A game in Royal Walkabouts:

C. Chapman (Kent) – C. Coates (Cheshire)

Correspondence

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 d4 exd4 4 e5 Ne4 5 Qe2 Bb4+ 6 Kd1 d5 7 exd6 f5 8 dxc7 Qxc7 9 Nxd4 O-O 10 Qc4+ Qxc4 11 Bxc4+ Kh8 12 Ke2 Re8 13 Bb5 Bd7 14 Kf3 Nc6 15 Nxc6 bxc6 16 Rd1 Nf6 17 Ba4 f4 18 h3 g5 19 a3 g4+ 20 hxg4 Bxg4+ 21 Kxf4 Ba5 22 Kg5

22...h6+ 23 Kxf6 Bd8+ 24 Rxd8 Raxd8 25 Bxh6 Rd5 26 Kf7 Re6 27 Bg7+ Kh7 28 Bb3 Rd7+ 29 Kf8

29...Re2 30 f4 Rxg7 31 Nc3 Rd2 32 Rh1+ Kg6 33 f5+ Bxf5 34 Rd1 Rf2 35 Ke8 Rb7 36 White resigns.

Sources: BCM, May 1915, page 173; Chess Amateur, August 1915, page 327; The “British Chess Magazine” Chess Annual 1915 by I.M. Brown (Leeds, 1916), page 171.

(7956)

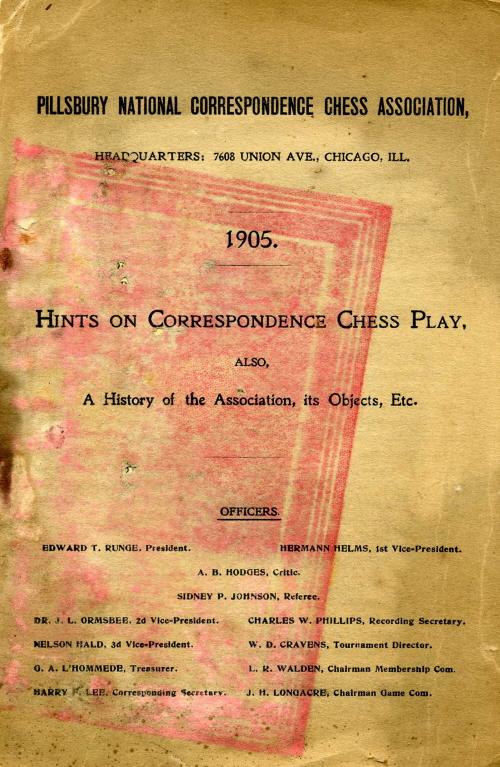

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) comes information about a scarce publication in his collection, a pamphlet produced by the Pillsbury National Correspondence Chess Association in 1905:

Mr Clapham writes:

‘The pamphlet has 12 pages, including the covers, and begins with a short history of the Association which states that it was founded in 1896 and was named as “a tribute to our master player Harry N. Pillsbury”. There follows a list of the accomplishments (two) of the Association and details of how its tournaments were arranged.

The second half of the publication has two articles, of about three pages each, giving general advice and recommendations on correspondence chess play. These are by the Reverend Leander Turney and Walter Penn Shipley.

There are no games, but the pamphlet does state that bulletins will be issued containing notable annotated games.’

(8002)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that pages 210-211 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1862 published a game which began 1 e4 Nf6 and was not played at odds:

Berwick Chess Club – Edinburgh Chess Club

Correspondence, November 1860-15 November 1861

Alekhine’s Defence

1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Ng8 3 d4 e6 4 Bd3 c5 5 Nf3 cxd4 6 O-O Nc6 7 Re1 d6 8 Bb5 d5 9 Nxd4 Bd7 10 c3 Bc5 11 Be3 Bxd4 12 Bxd4 Nge7 13 Bxc6 Bxc6 14 Qd3 O-O 15 f4 Nf5 16 Nd2 Qh4 17 Rf1 a6 18 a4 f6 19 exf6 gxf6 20 Rf3 h6 21 Nf1 Qh5 22 Rh3 Qf7 23 Ng3 Qh7 24 Nxf5 exf5 25 Qe2 Rae8 26 Rg3+ Kh8

27 Qh5 Re4 28 Qh4 Rxd4 29 cxd4 h5 30 a5 Be8 31 Re1 Qd7 32 Rge3 Bg6 33 Qg3 Bf7 34 Re7 Qb5 35 Qc3 Bg6 36 Qc5 Qxc5 37 dxc5 Rb8 38 Rd1 Be8 39 Rxd5 Bc6 40 Rxf5 Rd8 41 Rxf6 Rd1+ 42 Kf2 Rd2+ 43 Kf1 Resigns.

(8107)

Source: American Chess Bulletin, November 1918, page 234. The item came from the Evening World, 23 September 1918 and concerned a meeting of the Correspondence Chess League of America.

(8307)

From page 243 of CHESS, April 1966:

(8713)

‘Tells of’ is a formulation favoured by writers unconcerned with specifics. From page 133 of The Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1987):

‘B.H. Wood tells of this débâcle in a postal tournament. After 1 e4, Black replied: “...b6 2 Any, Bb7.” Now “any” is a useful postal chess time-saver; it’s shorthand for “any move you care to make”. So White replied with the diabolical “2 Ba6 Bb7 3 Bxb7” (and wins the rook as well).’

Where Wood told of this is not mentioned. We recall, though, that on page 279 of the June 1961 CHESS he reported that another magazine had told of a king’s-side version:

‘Chess Review tells of a postal chess player who rather recklessly wrote his White opponent thus: “Whatever you play, my first two moves are 1...P-KN3 and 2...B-N2.”

No prizes for guessing White’s first three moves.’

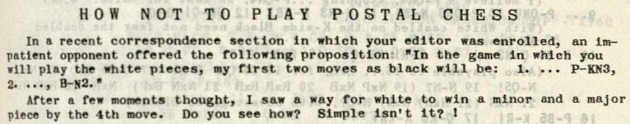

However, what Chess Review (April 1961, page 102) had told of contained no ‘Whatever you play ...’ remark and was merely a gleaning from an unspecified issue of another magazine:

‘We appreciatively take this item from the Ohio Chess Bulletin, which describes the “if” moves offered by an impatient player of the black pieces: “In the game in which you will play White, my first two moves as Black will be: 1...P-KN3, 2...B-N2.” Improbable as it may seem at first glance, White can now immediately apply the crusher. Do you see how he wins two pieces?’

Can a reader trace the relevant issue of the Ohio Chess Bulletin or quote other early versions of the story? Some later writers recounted it with details which may or may not have been invented; see, for example, page 66 of Playing Chess by Robert G. Wade (London, 1974).

(8942)

The request at the end of C.N. 8942 has been answered by the Cleveland Public Library, which has provided the following from page 22 of the February 1961 Ohio Chess Bulletin (Editor: David G. Wolford):

We now note an earlier report of the trick. On page 130 of the June 1941 CHESS a reader, J. Jackson of Caldbeck, wrote:

‘... in a recent match between Eire and Ulster, one of the Papists, at a highish board, opened with 1 P-Q4; his opponent replied: “1...P-KKt3; 2 Any, B-Kt2” and resigned on receipt of the laconic answer: “2 B-R6 ... 3 BxB”.’

In the electronic age a parallel may be drawn with ‘pre-moving’. See, for example, chapters four and five of Bullet Chess One Minute to Mate by H. Nakamura and B. Harper (Milford, 2009).

(8963)

Page 322 of CHESS, July 1971 reported on the disruption to correspondence chess arising from that year’s strike by postal workers in the United Kingdom. The magazine quoted a player:

‘Between my fifth and sixth moves in this game, I grew a moustache.’

(9337)

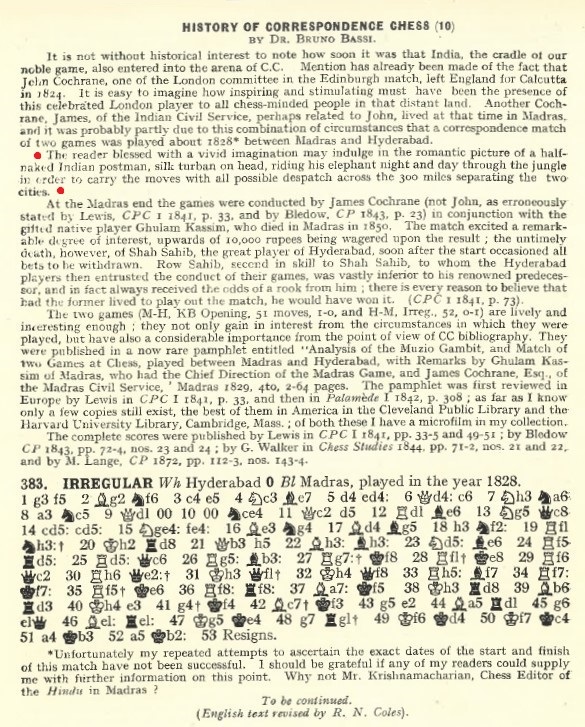

Concerning Indian Openings in Chess, Martin Sims (Upper Hutt, New Zealand) points out a remark in Ghulam Kassim’s annotations to the second game in the Madras-Hyderabad correspondence match, after 1 g3:

‘Many of the Indian Players commence their Game in this way.’

Source: page 45 of Analysis of the Muzio Gambit, and Match of Two Games at Chess, Played Between Madras and Hyderabad by Ghulam Kassim and James Cochrane (Madras, 1829). The book can be read on-line.

Our correspondent asks for information about a sourceless assertion by Andrew Soltis that elephants conveyed the chess moves. On page 10 of Chess Life, January 1990 Soltis wrote:

‘Take the case of the two-game match played more than 160 years ago between the masters of the Bay of Bengal port of Madras and the best players of Hyderabad, some 300 miles up into the interior of India. The surest way of sending the moves back and forth was via the regular mail pouches – that is, the ones carried by elephants.’

And:

‘The 2-0 victory by Madras is almost forgotten by history but should be remembered as The Elephant Match.’

A recent account of the contest is on pages 166-172 of volume one of L’histoire du jeu d’échecs par correspondance au XIXe siècle by Eric Ruch (Aachen, 2010). From pages 166-167:

‘Le lecteur imaginatif peut se représenter l’image romantique d’un postier indien à demi-nu, enturbanné, juché nuit et jour sur un éléphant, pour couvrir à travers l’épaisse jungle, les 300 miles de distance séparant les deux cités, pour y acheminer les coups d’échecs de nos joueurs par correspondance.’

The text, which was not in quotation marks, had a footnote mentioning an article by Bruno Bassi on page 327 of Mail Chess, March 1949. Courtesy of the Royal Library in The Hague, it is shown here:

The article was included in the collection of Bassi’s writings, The History of Correspondence Chess up to 1839 compiled by Egbert Meissenburg (Winsen/Luhe, 1965). An Italian translation, by Enzo Minerva, was published as a supplement to the 5/1991 issue of Telescacco nuovo, Rome under the title Storia del gioco per corrispondenza fino al 1839.

The correspondence match of the late 1820s was discussed on pages 31-33 of Indian Chess History 570 AD-2010 AD by Manuel Aaron and Vijay D. Pandit (Chennai, 2014). Page 31 stated:

‘An unlikely story is that the moves were despatched by golden caparisoned elephants carrying a private postman wearing a crimson turban and pearl-grey livery holding a blue lantern.’

From page 18 of Western Chess In British India (1825-1947) by Vijay D. Pandit (Nottingham, 2011):

‘We know that the moves were transported by liveried servants riding on the back of elephants ...’

The statement is unsubstantiated. We prefer to be told how we know what we are told that we know.

Have writers’ references to transportation by elephant merely misused Bruno Bassi’s light-hearted fancy beginning ‘The reader blessed with a vivid imagination may indulge in the romantic picture of ...’, or is there documentary evidence?

(9982)

An addition will be made to Unusual Chess Words, from page 33 of the book discussed in C.N.s 10087 and 10088, A Popular Introduction to the Study and Practice of Chess (London, 1851) written by S.S. Boden but published anonymously:

‘To prevent unlimitedly tedious prolongation in a correspondental game between two clubs, there is generally a fixed time allowed for each move ...’

(10111)

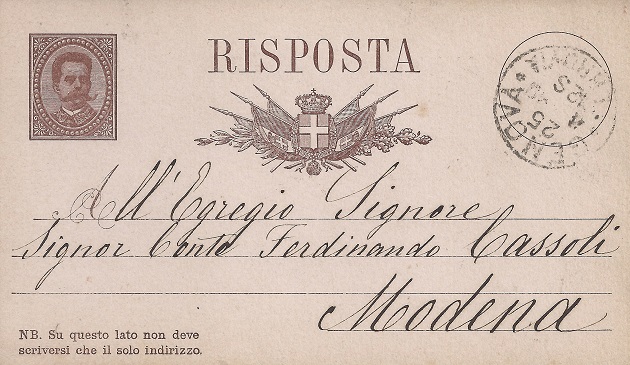

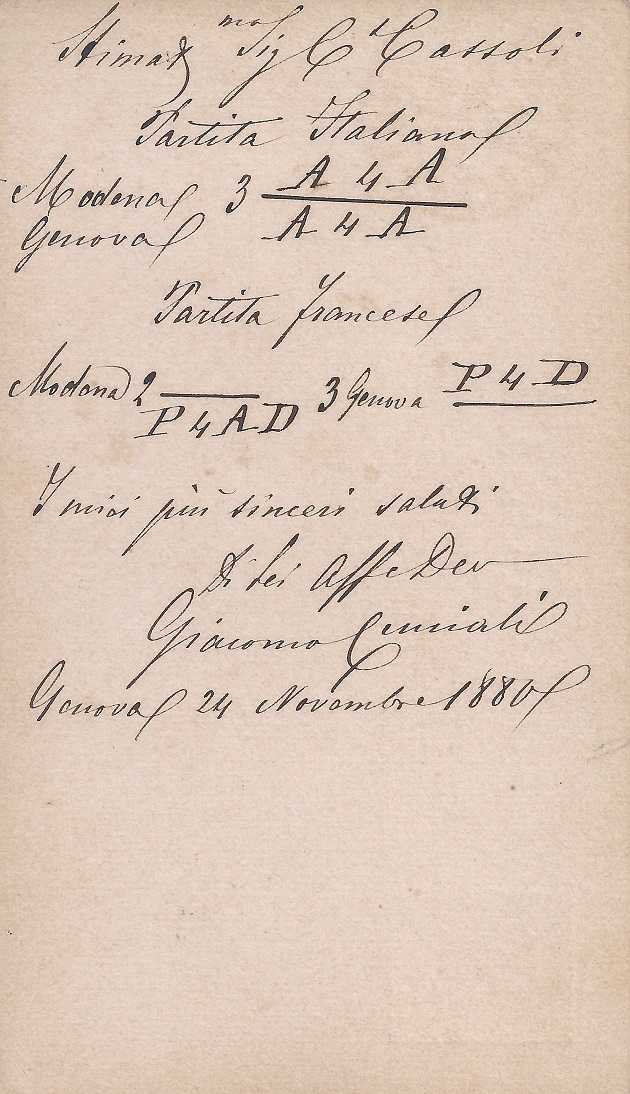

Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) writes:

‘I recently acquired several chess-related postcards addressed to Ferdinando Cassoli Lorenzotti, the strongest player in Modena after the departure of Discart and Bonetti from the city. Some of the cards contain moves in two still-unknown correspondence games between Modena and Genova played in the winter of 1880-81.

One of the games was played under the old Italian rules: no en passant captures; free castling (the king being allowed to go anywhere along his rank, and the rook anywhere between the king and e1/e8, but without being able to give check); restricted promotion (pawns able to promote to captured pieces only, but could also be left unpromoted). Unfortunately, the scores are incomplete and their use of the descriptive notation does not help. I have the following moves (the notes being by Giacomo Cuniali, the leader of the Genovese team, in my translation from the Italian):

Modena-Genova (played under the old Italian rules)

1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4 ... 5 ... 6 P-Q3 P-KR3 7 P-KR3 B-QN3 8 ... 9 ... 10 ... 11 ... 12 N-KN1 N-KB5 13 ... 14 P-Q4 P-KN4 15 PxP PxP At the moment, it seems to us, a statement about the final outcome of our games should be premature. 16 R-Q1 Q-K2 17 Q-K3 P-KN5 18 P-KR4 P-KN6 Our games are beginning to be interesting and therefore entertaining. [...] I proposed and endorsed the move 18...NxKP until the last minute, but none of my fellow players approved of it, since they considered it less good than 18...P-N6; I eventually accepted the latter, to respect the majority; moreover, 18...P-N6 promises to be a fine continuation as well. [...] If 18...NxP 19 P-KN3 B-B4 at this stage we tried many lines, but the outcome was always unclear because of their countless variations; rather, after many combinations White stood better. Having time, we could study the position more; but we are all busy from morning until night. 19 PxP N-KN5 In one game the attack is ours, in the other it is yours, but so far the situation is hopeless for neither of us. 20 Q-K1 N-R4 21 N-KB3 R-KN1 & K-KR1 [Italian castling] 22 QN-Q2 N(N5)-KB3 23 QN-KB1 R-KN5. Had Black played 23...R-N3 or 23...B-Q2 or 23...B-N5 [then] 24 R-Q3, followed by R-K3 and N(f3)-R2. Here I see White well entrenched, while Black is helpless, all the more so as Black, owing to his positions, would be lost with the slightest shock. [...] If we played 23...B-Q2 24 R-Q3 R-N3 25 R-K3 QR-KN1 26 N[3]-Q2, I said 26 N[3]-R2, thinking of 23...B-KN5. 24 Q-Q2 K-N2 The game, in my opinion, is decidedly drawn because of the move 24 Q-Q2; but we could avoid it only by jeopardizing the game. 25 Q-Q8 QxQ 26 RxQ NxKP 27 BxP KxB If 27 NxKP+ K-K2.

Genova-Modena (played under the standard international rules)

1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4 ... 5...N-KB3 6 B-Q3 B-K2 7 Castles ... 8 ... 9 ... 10 ... 11...NxB 12 QxN ... 13...P-QR3 14 N-QN3 N-KN5 15 NxB At the moment, it seems to us, a statement about the final outcome of our games should be premature. 15...QxN 16 P-KN3 Q-K4 17 B-B4 Q-R4 18 P-KR4 Our games are beginning to be interesting and therefore entertaining. 18...B-B4 19 Q-Q2 In one game the attack is ours, in the other it is yours, but so far the situation is hopeless for neither of us. In this game we made a very bad move, which was enough for us to be attacked; it was Nd4-b3. 19...N-B3 20 P-KB3 Q-N3 21 R-KB2 KR-K1 22 N-Q4 P-KR4 23 P-QB3 N-Q2 24 K-R2 There is nothing for either party to do, in my opinion, as always happens in the games in which the French and the Sicilian Defences are adopted. 24...N-B4 25 R-KN1 N-K3 26 NxB If 26...QxN 27 B-K3.

It would be interesting to reconstruct the full scores of both games. Knowing their openings would be helpful, but they are stated ambiguously. The Modena-Genova contest is called the “Italian Game”, but that may mean either “the opening is an Italian Game” or “the game is played under the Italian rules”; similarly, the Genova-Modena game is often called “French Game”, which may mean either “the opening is a French Game” or “the game is played under the French rules”. In Italy the international rules were called “French” because they were first codified in a book printed in Paris in 1668 and were subsequently sanctioned by Philidor’s treatise. To complicate matters further, on the postcards the Genova-Modena game is once called “English” and once alluded to as “Sicilian”.

I propose a reconstruction of the “Italian” Modena-Genova game:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 Castles (Kh1, Rf1) d6 6 d3 h6 7 h3 Bb6 8 Qe2 Ne7 9 Be3 Ng6 10 Bxb6 axb6 11 Bb3 c6 12 Ng1 Nf4 13 Qf3 b5 14 d4 g5 15 dxe5 dxe5 16 Rd1 Qe7 17 Qe3 g4 18 h4 g3 19 fxg3 Ng4 20 Qe1 Nh5 21 Nf3 Castles (Kh8, Rg8) 22 Nbd2 Ngf6 23 Nf1 Rg4 24 Qd2 Kg7 25 Qd8 Qxd8 26 Rxd8 Nxe4 27 Bxf7 Kxf7 (28 Nxe5+ Ke7).

Can any improvements be made to my reconstruction, and is it possible to reconstruct the second game? I should also like to know whether any other postcards relating to the two games have survived.’

(10687)

Richard Forster (Zurich) proposes this reconstruction for the game played under the standard international rules:

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 c5 4 Nf3 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 Bd3 Be7 7 O-O O-O 8 exd5 exd5 9 Be3 Nc6 10 Nce2 Ne5 11 Ng3 Nxd3 12 Qxd3 Bd6 13 Ngf5 a6 14 Nb3 Ng4 15 Nxd6 Qxd6 16 g3 Qe5 17 Bf4 Qh5 18 h4 Bf5 19 Qd2 Nf6 20 f3 Qg6 21 Rf2 Rfe8 22 Nd4 h5 23 c3 Nd7 24 Kh2 Nc5 25 Rg1 Ne6 26 Nxf5 Qxf5 27 Be3.

(10691)

Fabrizio Zavatarelli reports that he has obtained a further 14 postcards addressed to Ferdinando Cassoli Lorenzotti and can offer new proposals for reconstruction of the two games:

Modena-Genova

Correspondence, November 1880-February 1881 or later

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 Castles (Kh1, Rf1) d6 5 c3 Nf6 6 d3 h6 7 h3 Bb6 8 Be3 Ne7 9 b4 Ng6 10 a4 c6 11 Bxb6 Qxb6 12 Ng1 Nf4 13 Qf3 Qd8 14 d4 g5 15 dxe5 dxe5 16 Rd1 Qe7 17 Qe3 g4 18 h4 g3 19 fxg3 Ng4 20 Qe1 Nh5 21 Nf3 Castles (Kh8, Rg8) 22 Nbd2 Ngf6 23 Nf1 Rg4 24 Qd2 Kg7 25 Qd8 Qxd8 26 Rxd8 Nxe4 27 Bxf7 Kxf7. If 28 Nxe5+ Ke7 (Cuniali).

Genova-Modena

Correspondence, November 1880-February 1881 or later

1 e4 e6 2 Nf3 c5 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nc6 5 Be3 Nf6 6 Bd3 Be7 7 O-O d5 8 exd5 exd5 9 Nc3 O-O 10 Nce2 Ne5 11 Ng3 Nxd3 12 Qxd3 Bd6 13 Ngf5 a6 14 Nb3 Ng4 15 Nxd6 Qxd6 16 g3 Qe5 17 Bf4 Qh5 18 h4 Bf5 19 Qd2 Nf6 20 f3 Qg6 21 Rf2 Rfe8 22 Nd4 h5 23 c3 Nd7 24 Kh2 Nc5 25 Rg1 Ne6 26 Nxf5. If 26...Qxf5 27 Be3 (Cunali).

Moves in italics are deductions by our correspondent, who has also provided another card:

(10737)

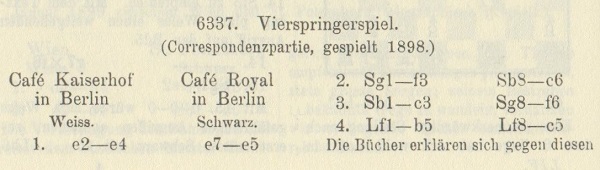

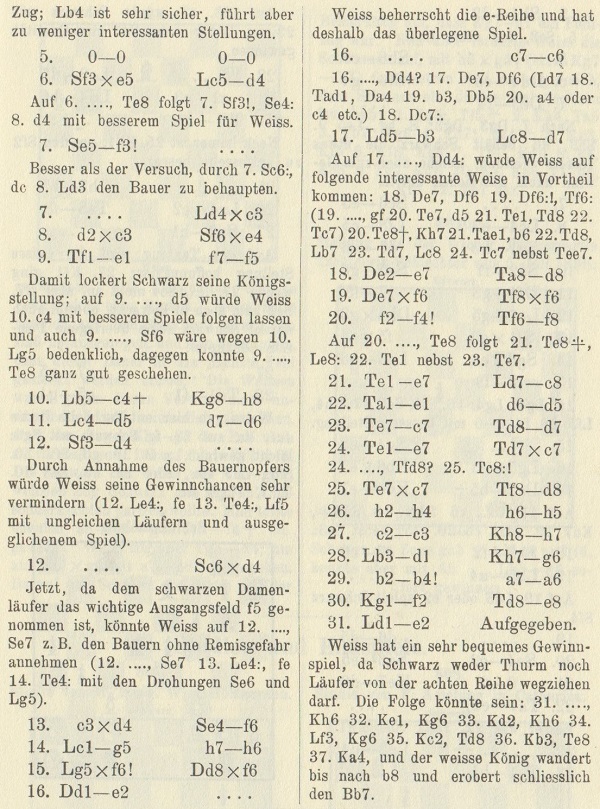

After 31 Be2, was Black justified in resigning?

(10992)

After 31 Be2 Black resigned on the grounds that a decisive march by the white king to b8 is unpreventable.

The game, played by correspondence in Berlin between the Café Kaiserhof and the Café Royal, was published on pages 50-51 of the February 1899 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bc5 5 O-O O-O 6 Nxe5 Bd4 7 Nf3 Bxc3 8 dxc3 Nxe4 9 Re1 f5 10 Bc4+ Kh8 11 Bd5 d6 12 Nd4 Nxd4 13 cxd4 Nf6 14 Bg5 h6 15 Bxf6 Qxf6 16 Qe2 c6 17 Bb3 Bd7 18 Qe7 Rad8 19 Qxf6 Rxf6 20 f4 Rff8 21 Re7 Bc8 22 Rae1 d5 23 Rc7 Rd7 24 Re7 Rxc7 25 Rxc7 Rd8 26 h4 h5 27 c3 Kh7 28 Bd1 Kg6 29 b4 a6 30 Kf2 Re8 31 Be2 Resigns.

From page 13 of Schachjahrbuch für 1899. II. Theil by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1900):

Richard Forster writes:

‘The best line may be 31...Rh8 32 Bf3 Kf6, and now if 33 Ke2 then 33....g6 34 Kd2 Rg8 35 Kc2 Ke6 36 Kb3 Kd6 37 Rh7 b6. The computers suggest 33 a4 g6 34 b5, which wins a pawn and probably gives very good winning chances, but the game is not yet over.’

(10997)

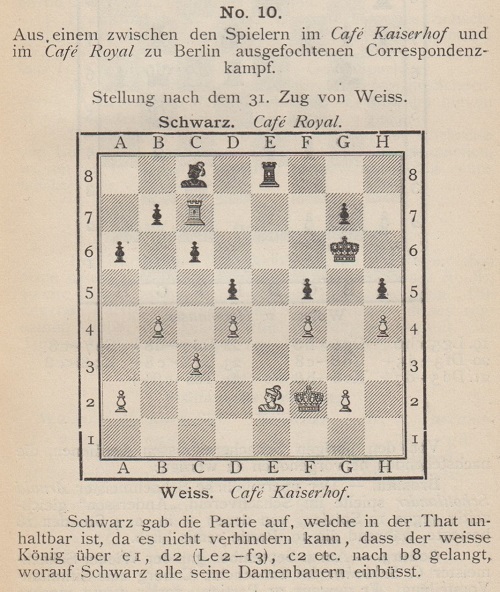

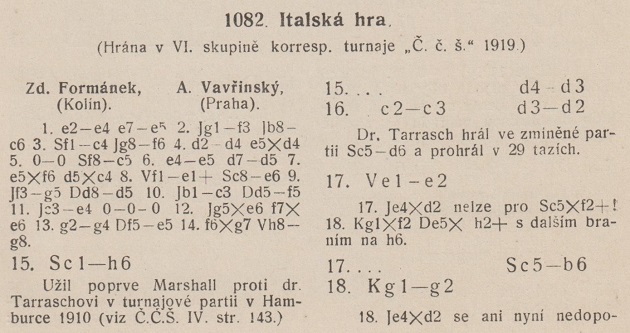

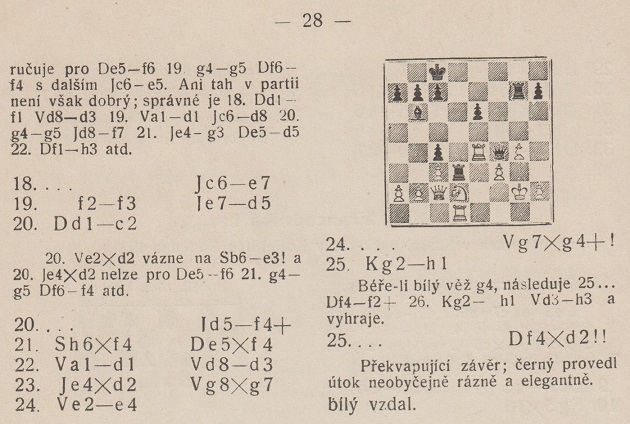

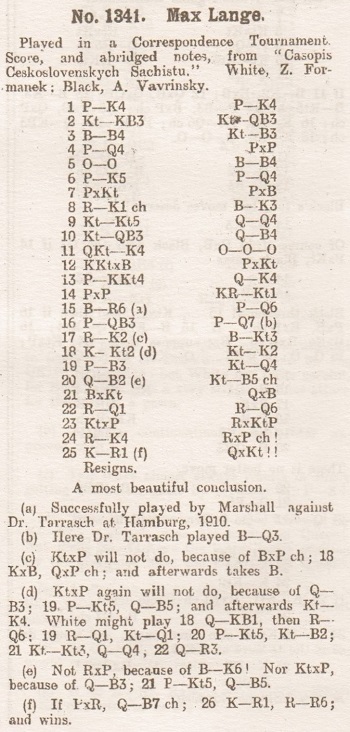

A correspondence game played in 1919 between Zd. Formánek and A. Vavřinský:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 O-O Bc5 6 e5 d5 7 exf6 dxc4 8 Re1+ Be6 9 Ng5 Qd5 10 Nc3 Qf5 11 Nce4 O-O-O 12 Nxe6 fxe6 13 g4 Qe5 14 fxg7 Rhg8 15 Bh6 d3 16 c3 d2 17 Re2 Bb6 18 Kg2 Ne7 19 f3 Nd5 20 Qc2 Nf4+ 21 Bxf4 Qxf4 22 Rd1 Rd3 23 Nxd2 Rxg7 24 Re4 Rxg4+ 25 Kh1

25...Qxd2 26 White resigns.

The score is taken from pages 27-28 of Časopis Československých Šachistů, February 1920:

It was also published on page 352 of the September 1920 Chess Amateur:

(11529)

See our feature article on Marshall for further details on this opening.

Yasser Seirawan (Hilversum, the Netherlands) notes the following paragraph in an article on correspondence chess by Greg Keener in the New York Times, 9/10 November 2022:

‘Looking back even further, it is believed that King Henry I of England, whose reign lasted from 1100 to 1135 A.D., played correspondence chess with his counterpart in France, King Louis VI, who reigned from 1108 until 1137. The French enlightenment writer and luminary Voltaire is noted to have played correspondence chess with his pupil Frederick the Great of Prussia. Their moves were securely escorted by royal courier between Berlin and Paris. It’s also thought that Venetian merchants played correspondence chess with one another, contemplating their next moves on voyages between ports.’

Such stuff can be found on sourceless sites at the press of a button, but what can be written properly on the topic, without recourse to ‘it is believed that’, ‘is noted to have played’ and ‘it’s also thought that’?

(11924)

Which master was challenged to play a game as Black against 1 e4 e5 2 Ke2?

Simon Alapin (Deutsches Wochenschach, 7 January 1894)

The answer is Simon Alapin, in 1892, the challenger being Max Lange. No such game was played, but they did agree to contest one correspondence game, with Alapin required to play 1 e4 e5 2 Ne2.

Page 299 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 21 August 1892 had carried a letter from Alapin extolling 2 Ne2 and claiming that it should be named after him. Max Lange made unfavourable mention of this in a long article about chess theory on pages 257-264 of the September 1892 Deutsche Schachzeitung. On page 262 he suggested that 2 Ne2 deserved no more theoretical attention than 2 Ke2, which also blocks the king’s bishop and the queen.

It was not until the 7 January 1894 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach that Alapin related, on pages 4-10, what had happened during the interval of more than a year. Around the time of the September 1892 article, Max Lange had challenged him to a correspondence game in which he would take Black against Alapin’s 1 e4 e5 2 Ne2 and also proposed playing a game in which he, as White, would begin 1 e4 e5 2 Ke2 against Alapin, in order to ‘balance the chances’.

Alapin agreed only to the 1 e4 e5 2 Ne2 game, and stated that in the circumstances it became a matter of life or death. In addition to the exact dates when the game began and ended (see below), Alapin even published the reflection time: 37 days for White and 149 for Black, the remainder being postal time. Alapin then annotated the game, over six pages.

Simon Alapin – Max Lange

Correspondence, 23 September 1892 – 5 September 1893

Alapin’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Ne2 Nc6 3 d4 Qh4 4 d5 Bc5 5 Ng3 Nce7 6 Nd2 Qf6 7 f3 Qh4 8 Nb3 Bb6 9 d6 Nc6 10 c4 cxd6 11 Qxd6 Nf6

12 Kd1 Nh5 13 Nf5 Qd8 14 g4 g6 15 Ne3 Qf6 16 Qxf6 Nxf6 17 c5 Bd8 18 Nc4

18...d5 19 Nd6+ Ke7 20 g5 Nd7 21 exd5 Nb4 22 Bc4 Nxc5 23 Nxc5 Kxd6 24 Ne4+ Ke7 25 Bd2 a5 26 a3 Na6 27 d6+ Kf8 28 Bc3 h6 29 Bxe5 Rh7 30 Nf6 Bxf6 31 gxf6 Bd7 32 Rc1 Nb8 33 Bb5 Nc6 34 Re1 Rh8 35 Bxc6 Bxc6

36 Rxc6 bxc6 37 d7 Rd8 38 Bd6+ Kg8 39 Re7 g5 40 Kc2 Kh7 41 Kc3 Kg6 42 Kc4 Kxf6 43 Kc5 h5 44 Kxc6 Resigns.

The game was shown, from an undated scrapbook of Walter Penn Shipley’s, in C.N. 771 (see page 49 of Chess Explorations) with this concluding remark by Showalter in the New York Recorder:

‘It would be difficult indeed to laud too highly the masterly style in which Herr Alapin conducted his attack in this game, the more especially as applied to the latter half of it. Truly, correspondence chess is the best chess, after all.’

The date of Showalter’s column was 28 January 1894.

We show none of the nineteenth-century material here, given that it is available online (e.g. via Google Books or Chess Archaeology).

(12065)

The Chess Wit and Wisdom of W.E. Napier provides many quotes from Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). Number 166:

‘It has been my observation all through the years that the master player nearly always makes lively games at correspondence, even tho his play vis-à-vis is governed by more conservative models.

The paradox is baffling.

The only theory I have adduced is that the social nature of mail exchanges quite subordinates mere winning to joyful, yawing chess.

In match games over the board, the killing instinct necessary to success is the same that men take into Bengal jungles, – for a day. A killing instinct which survives the day and endures month in and month out, is stark pantomime; and mail chess is the gainer by it.’

See also, in particular, ‘The Swiss Gambit’, Wade v Bennett, Announced Mates, Leo Tolstoy and Chess and The Chess Historian R.N. Coles.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.