Edward Winter

See C.N. 8692 below.

An extract from a letter dated 2 March 1886 written by Sam Loyd to Steinitz and published on pages 71-72 of the March 1886 issue of the International Chess Magazine:

‘In regard to the benefits and advantages of problem solving, I can only reply to the argument that so many good solvers are poor players, with the argument of Horace Greely, before he became a Democratic candidate, that, whereas he was “not prepared to assert that every Democrat was a horse-thief, he was willing to assert that every horse-thief was a Democrat”, just so, while I cannot say that solvers are good players, yet the best solvers I ever met were Morphy, Kolisch, Steinitz, Zukertort, Blackburne, Mackenzie and Mason, all of whom play a fair game.’

(1113)

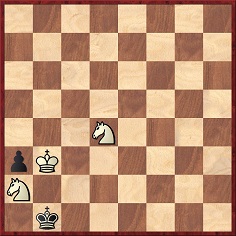

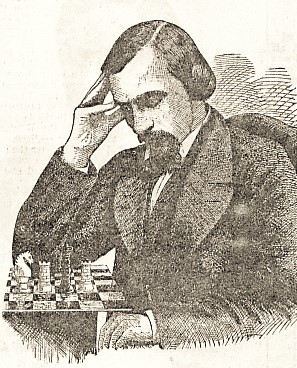

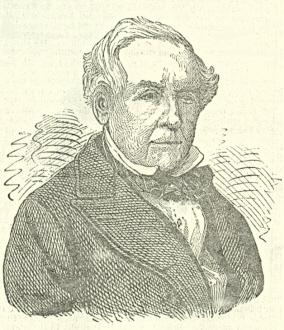

C.N. 3294 gave a picture of Staunton and asked about its origins. We can now report that the artist was Samuel Loyd, who reproduced his sketches/woodcuts in the Scientific American Supplement, one per week during the column’s run from 11 August 1877 to 3 August 1878. The Staunton illustration appeared on 6 October 1877 (page 1470), and Loyd wrote:

‘I have placed on the board a little five-move knight problem that I showed to him during my last visit to London. I dare say a microscopic observation would reveal the two-move position on the back of the book.’

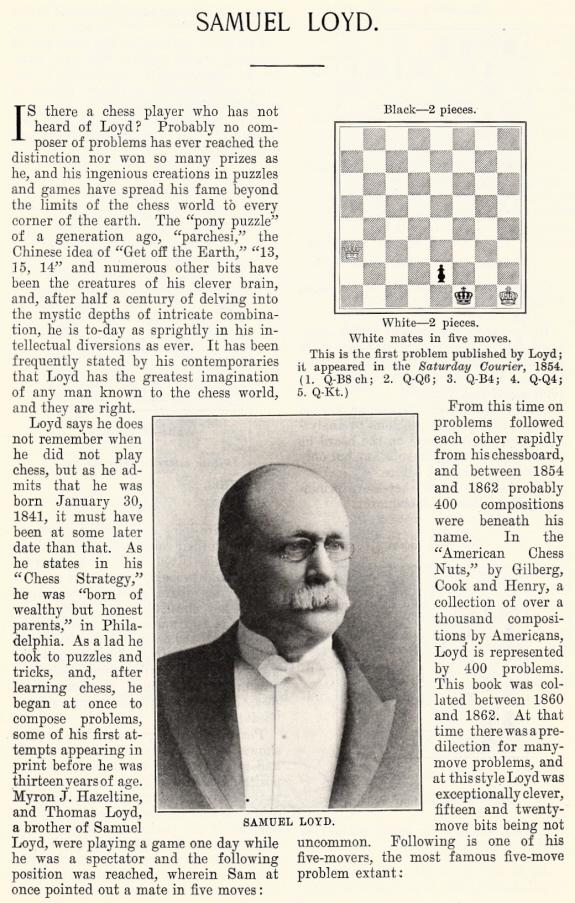

We have managed to identify the board position as a composition by Loyd published on page 103 of the Chess Monthly, April 1858 (although the pieces are in the bottom left, and not bottom right, corner):

Mate in five: 1 Nc6 Ka1 2 Kc2 Kxa2 3 Nb4+ Ka1 4 Kc1 a2 5 Nc2. [See too Pictures of Howard Staunton.]

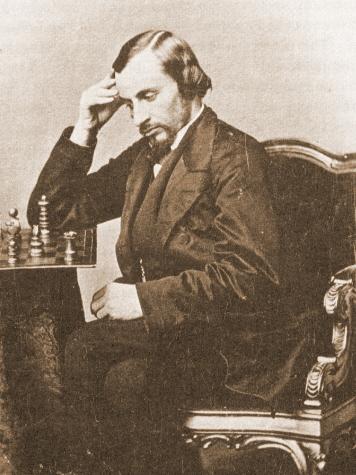

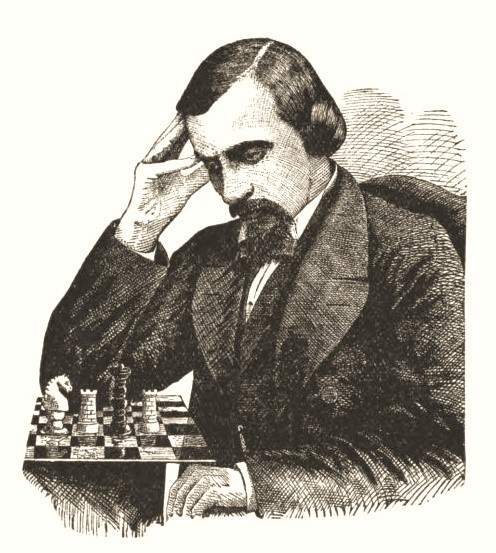

The previous week (Scientific American Supplement, 29 September 1877, page 1454) Loyd had presented:

‘… a portrait of Mr Steinitz as we sketched the little giant half a score of years ago while he was working out a problem to draw with a bishop against knight and pawn.’

‘As we progress … with our proposed record of the important chess events of the past, it will be readily understood why, by common consent, Mr Steinitz has become to be looked upon as the recognized chess champion of Europe.

We have enjoyed the most friendly relations with Mr Steinitz and found him the very pink of honor, and the most jovial little fellow in the world, ready to fight you at chess, or die sooner than give up on some little etiquetical point that he considers correct and proper. His able management of the chess department of the London Field is gaining him a world-wide reputation as the analyst of the day.’

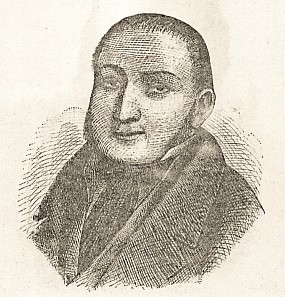

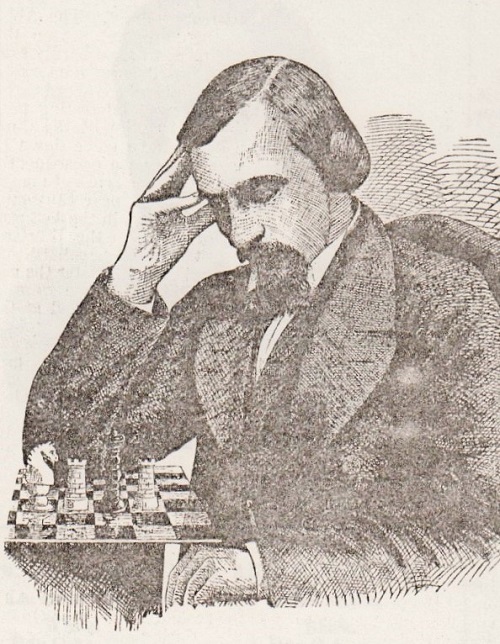

On page 1566 of the Scientific American Supplement, 17 November 1877 Loyd gave a portrait of Harrwitz ‘as we saw him many years ago, during our first visit to Paris’. In fact, the picture is very similar to a well-known photograph of Harrwitz.

It will be noted that the board positions are different, and regarding his sketch Loyd wrote:

‘Problem from the page of history. The position on Mr Harrwitz’s chess board gives the clue to this problem, and shows that although the king is mated in the middle of the board with knight and rooks, yet it could not occur in actual play, which proves that the little curate had been playing points to his friend, who was justly astonished at the critical position of his king, and in asking how it came so could well vow “to tell it to neither king, rook nor knight”.’

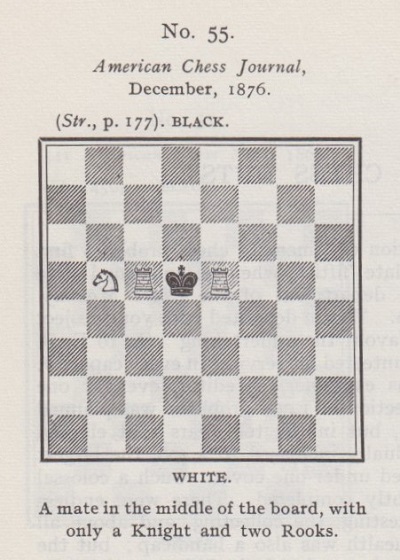

A similar position (white knight on b5, white rooks on c5 and e5, black king on d5) was given in the American Chess Journal, December 1876; see pages 52-53 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913).

Finally, on 6 April 1878 (page 1884) Loyd’s column gave his depiction of Labourdonnais:

This is based on the well-known (and only known) picture of the Frenchman, and Loyd wrote, ‘our portrait is taken from an oil painting made in London a short time before his death’.

This brings to mind Staunton’s remark on page 159 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1842 when welcoming the French magazine Le Palamède:

‘We must, however, protest against the insertion of such lugubrious twaddle as “The last moments of Labourdonnais”, from – Bell’s Life in London! and the lithographic enormity, from the same classic source we presume, presented as the portrait of that distinguished chessplayer.’

On the subject of lugubriousness, our present item concludes with the following disclosure by Loyd concerning Labourdonnais:

‘It is not generally known that a plaster cast was taken from his features at the time of his death and was brought to this country, and is at present in the possession of Mr Eugene B. Cook, the distinguished problemist, who prizes it most highly and takes peculiar pride in showing the stray locks of hair and whiskers that still adhere to the plaster.’

(3397)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) writes:

‘The woodcut of Steinitz also features a Loyd composition (number 16 in Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems). The incorrectly turned board is presumably Loyd having a little fun at Steinitz’s expense. The woodcut reminds me of a photograph of Steinitz playing Anderssen on page 104 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974).’

Below is the composition in question, which originally appeared on page 41 of the Chess Monthly, February 1860:

White to play and draw

1 Bd7 h2 2 Bc6+ Kg1 3 Bh1 Kxh1 4 Kf2.

(3400)

See also C.N.s 9930 and 9935 below.

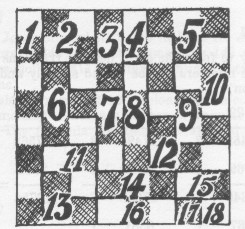

In C.N. 3467 Owen Hindle (Cromer, England) suggested that the photograph of James Leonard reproduced in C.N. 3451 might be from Samuel Loyd’s ‘photographic chessboard’, and we asked for further details about that Loyd item. It has now been found by John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA), who has kindly forwarded a copy:

(3590)

See too Chess Photograph Collages.

From C.N. 3555:

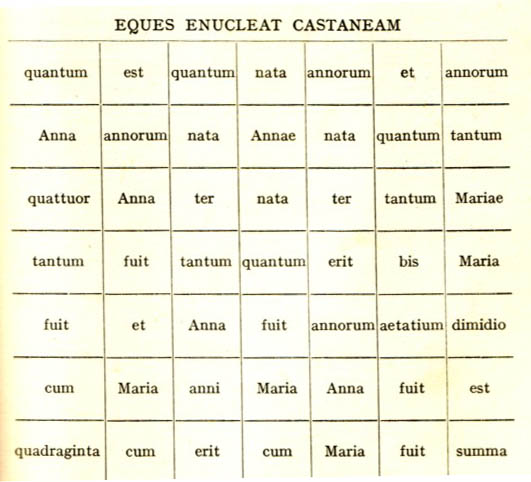

‘When I met Professor Graeme Atta the other day he showed me an interesting old manuscript book which he had come across when he was browsing among the second-hand bookstalls in Charing Cross Road. The book plate was almost indecipherable, but as far as I could make out bore the inscription “ex libris Samueli Loyd”. One of the pages contained a curious Latin cryptogram which seems to be of more than passing interest. Here is a copy of it:

Quot annos nata est Maria?’

Source: Caliban’s Problem Book by Hubert Phillips (‘Caliban’), S.T. Shovelton and G. Struan Marshall (London, 1933), page 127.

For solution click here.

Hubert Phillips ascribed the ‘How old is Mary?’ puzzle to Loyd, and that would seem proper; see, for instance, page 8 of More Mathematical Puzzles of Sam Loyd (New York, 1960). On the other hand, we note that the identical puzzle appeared on page 12 of the collection of H.E. Dudeney’s posers, A Puzzle-Mine by J. Travers (undated, but post-1930).

(3633)

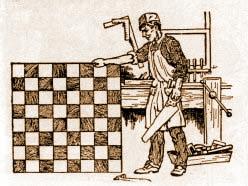

A problem by Sam Loyd given in C.N. 3596:

‘This clever young carpenter received a chest of tools for a Christmas present, and immediately set to work to make a fine chessboard to present to Dr Lasker, the chess champion of the world. Dr Lasker is a great mathematician and puzzlist as well as a marvelous chessplayer, but can he beat our puzzlists in discovering the largest number of different pieces that the carpenter could have used in making this board?

Each piece must be made up of squares. One piece can be a single black square, another piece a single white square. Only one piece may consist of two squares, because all two-square pieces are alike. But a three-square piece has four different forms – a straight row with a black square in the middle, a straight row with a white square in the middle, a crooked piece with one black square, and a crooked piece with one white square. When you have divided the checkerboard into the greatest number of pieces, you will have solved the puzzle.’

Loyd gave the following illustration to show that the diagram could be divided into 18 pieces:

This poser has been taken from pages 51 and 145 of More Mathematical Puzzles of Sam Loyd by M. Gardner (New York, 1960). Gardner added the following observation:

‘There are many different ways that the board can be divided into 18 different pieces. As an interesting exercise, the reader may try to work out a proof that 18 is indeed the maximum number.’

(3614)

See also Chess Puzzles.

From page 106 of H.E. Dudeney’s 1917 book Amusements in Mathematics:

‘Some years ago the puzzle was proposed to construct an imaginary game of chess in which White shall be stalemated in the fewest possible moves with all the 32 pieces on the board. Can you build up such a position in fewer than 20 moves?’

The solution on page 232 was as follows:

‘Working independently, the same position was arrived at by Messrs. S. Loyd, E.N. Frankenstein, W.H. Thompson and myself. So the following may be accepted as the best solution possible to this curious problem:

1 d4 e5 2 Qd3 Qh4 3 Qg3 Bb4+ 4 Nd2 a5 5 a4 d6 6 h3 Be6 7 Ra3 f5 8 Qh2 c5 9 Rg3 Bb3 10 c4 f4 11 f3 e4 12 d5 e3. And White is stalemated.

We give a diagram of the curious position arrived at. It will be seen that not one of White’s pieces may be moved.’

It is Loyd’s name which is most commonly associated with the 12-move stalemate game, in the following version: 1 d4 d6 2 Qd2 e5 3 a4 e4 4 Qf4 f5 5 h3 Be7 6 Qh2 Be6 7 Ra3 c5 8 Rg3 Qa5+ 9 Nd2 Bh4 10 f3 Bb3 11 d5 e3 12 c4 f4.

See, for instance, page 207 of The Puzzle King by S. Pickard (Dallas, 1996), the source being stipulated on page 237 as ‘1906, Lasker’s Chess Magazine’.

That 1 d4 d6 version of the game, with humorous annotations, did indeed appear in an article by Loyd on pages 137-138 of the January 1906 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine. It was subsequently reproduced and discussed on pages 127-129 of A.C. White’s Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913), where White wrote:

‘The most quotable of Loyd’s contributions to Lasker’s is the amusing imaginary game ... in answer to the question: in how few moves can a game be played in which White is stalemated without loss on either side? J.C.J. Wainwright had found an ingenious solution in 15 moves (Sunny South, 1887), and methods analogous to Loyd’s were discovered independently, but almost simultaneously, by H.E. Dudeney, E.N. Frankenstein and W.H. Thompson. As far as I know, the actual priority has not been established. Loyd’s solution gains a good deal by the parody on conventional annotation contained in the notes to the moves made.’

Alain Campbell White

Michael McDowell points out to us that T.R. Dawson wrote as follows about the synthetic game on page 22 of Ultimate Themes (Thornton Heath, 1938):

‘G.R. Reichelm [sic] proposed this theme in 1882 and gave a solution in 16. He republished this work in Sunny South in 1887, with a prize offer. J.C.J. Wainwright won the prize with a solution in 15, C.H. Wheeler second in 16. W.A. Shinkman saw this reprint and gave a solution in 13 in Brownson’s Journal, February 1887, whereupon C.H. Wheeler obtained the existing minimum solution in 12 and gave it in Sunny South in 1887: 1 a4 c5 2 d4 d6 3 Qd2 e5 4 Qf4 e4 5 h3 Be7 6 Qh2 Bh4 7 Ra3 Be6 8 Rg3 Bb3 9 Sd2 Qa5 10 d5 e3 11 c4 f5 12 f3 f4, stalemate as diagram, a lovely thing. But C.H.W. pointed out also the alternatives Black Qh4, KBb4, QRPa5, or Black Qh4, KBa5, also in 12 moves. Unfortunately for him, the problem was again re-set in the Leeds Mercury Supplement, 1895, and from there taken into the New York Clipper, 1895. In both these publications, the above three solutions were re-discovered by H.E. Dudeney, E.N. Frankenstein, S. Loyd and W.H. Thompson. As is well known, Loyd wrote an amusing anecdote round the solution in Lasker’s Magazine, January 1906, and thereby scooped all the credit! Now, I hope, it will return to its legitimate owners. This little history is based on a re-examination of the Sunny South chess column by J.C.J.W., and my study of the Leeds Mercury and N.Y. Clipper, while I had also the original m.s. solutions and notes of C.H.W., J.C.J.W. and E.N.F.’

Above his diagram of the final position Dawson gave ‘G.R. Reichelm [sic], Solved by C.H. Wheeler. Brentano, Jan. 1882’. We add the exact reference for the task, on page 455 of the January 1882 issue of Brentano’s Chess Monthly: it was one of 18 ‘nuts’ set by Reichhelm and read, ‘Play so that White can get stalemated in 16 moves without losing a man’. Can a reader send us any of the other, slightly longer solutions referred to by Dawson?

Gustavus Charles Reichhelm

On pages 6-7 of Chess Life, February 1981, in an article subsequently included on pages 93-97 of his book Karl Marx Plays Chess (New York, 1991), A. Soltis related that C.H. Wheeler found the 12-move game in 1887, as did K. Whyld on page 199 of the April 1992 BCM. Both failed to specify any source for their information. Soltis, furthermore, confused matters on page 11 of his book Sam Loyd His Story and Best Problems (Dallas, 1995) by writing:

‘... around the turn of the century there was an ongoing effort to construct the shortest possible game ending in stalemate. Eventually an Englishman named C.H. Wheeler found a 12-mover that went 1 d4 d5 2 Qd2 e5 3 a4 e4 4 Qf4 f5 5 h3 Be7 6 Qh2 Be6 7 Ra3 c5 8 Rg3 Qa5+ 9 Nd2 Bh4 10 f3 Bb3 11 d5 e3 12 c4.’

Such dense inaccuracy is quite common in Soltis’ output, and it should be noted that:

i) The construction effort took place in the 1880s, and not ‘around the turn of the century’;

ii) It was not ‘the shortest possible game ending in stalemate’ but the shortest possible game ending in stalemate without captures;

iii) C.H. Wheeler was American, not English (as Soltis could have discovered by consulting Gaige’s Chess Personalia);

iv) Black’s first move should read 1...d6, not 1...d5;

v) Soltis omitted the move which brought about the stalemate, i.e. 12...f4.

The following appeared on page 189 of the May 1914 BCM:

‘The Tijdschrift gives news of the “Batavian Capablanca”, Si Narsar. His simultaneous play at Java seems to have electrified the players in those distant parts; and we quote one of his recent games from the Tijdschrift:

White: Si Narsar Black: L...d. 1 a4 f5 2 h3 d6 3 d4 e5 4 Qd2 e4 5 Qf4 Be7 6 Qh2 Be6 7 Ra3 c5 8 Rg3! Qa5+ 9 Nd2 Bh4 10 f3 Bb3? 11 d5 (White is in a bad way, and speculates now on the avariciousness of his opponent.) 11...e3 12 c4 (A very fine piece of speculation.) 12...f4 (Black naturally falls into the trap. Stalemate. A most remarkable position.)’

This leg-pull was discussed by W.H. Watts on page 259 of the July 1914 BCM , with reference made to Loyd and Lasker’s Chess Magazine.

Loyd’s spoof article (i.e. with the 1 d4 d6 version of the game) was plagiarized in an unsigned article entitled ‘Justicia Reglamentaria’ on pages 157-158 of El Ajedrez Americano, October 1935. The players in the parody were named as Jesús Fernández and Ramón Pérez.

Half a century ago there was a brief revival of interest in the theme of short stalemate games after the following appeared, under the title ‘A record for all time?’, on page 351 of CHESS, 28 May 1955:

‘In how few moves, from the start-of-game position, can stalemate come about? Sam Loyd worked out a train of 12 moves, producing a position which has become world famous.

L.A. Edelstein of Oxford University has found a new solution in 11 moves only, totally different from Loyd’s.

He has the thrill of breaking a 71-year-old record, and establishing a new one which may stand for ever! Here is his version: 1 h4 e5 2 c4 d5 3 Qb3 dxc4 4 e4 cxb3 5 axb3 Qxh4 6 Rxa7 Rxa7 7 g4 Bxg4 8 Na3 Qxh1 9 Nf3 Bxa3 10 Ke2 Bb4 11 Ke1 Bxf3 Stalemate!’

It is not known why CHESS referred to a ‘71-year-old record’ (what had supposedly happened in 1884?), but the excitement was ill-founded and the ‘record for all time’ was flattened in the following issue (18 June 1955, page 383) after receipt of ‘a flood of letters’:

‘Firstly our Problem Editor [C.S. Kipping] corrects us by pointing out that S. Loyd improved on his stalemate in 11, with a solution in ten, as follows; his 12-move effort being subject to the condition: “No piece or pawn captured”.’

Then CHESS gave the famous ten-move Loyd game with captures, from Le Sphinx of October 1866 (see, for instance, page 58 of A.C. White’s book on Loyd): 1 e3 a5 2 Qh5 Ra6 3 Qxa5 h5 4 Qxc7 Rah6 5 h4 f6 6 Qxd7+ Kf7 7 Qxb7 Qd3 8 Qxb8 Qh7 9 Qxc8 Kg6 10 Qe6 Stalemate.

CHESS added that a number of readers, including Edelstein himself, had found that his own final position ‘can be reached in ten moves instead of 12!’ [sic – ten moves instead of 11], one possibility being 1 h4 e5 2 c4 d5 3 Qb3 dxc4 4 e4 cxb3 5 axb3 Qxh4 6 Ra4 Qxh1 7 g4 Bxg4 8 Nf3 Bxf3 9 Na3 Bxa3 10 Rb4 Bxb4 Stalemate.

Finally here, as regards the first discovery of the 12-move game without captures, it will be noted that when H.E. Dudeney and A.C. White named four persons they omitted the real discoverer, C.H. Wheeler (1846-1927). It must be hoped that justice will, at long last, be done to Wheeler (who was, according to W.A. Shinkman on page 210 of the December 1927 American Chess Bulletin, ‘exceedingly modest of his own powers’) for being the real inventor of 1 a4 c5 2 d4 d6 3 Qd2 e5 4 Qf4 e4 5 h3 Be7 6 Qh2 Bh4 7 Ra3 Be6 8 Rg3 Bb3 9 Nd2 Qa5 10 d5 e3 11 c4 f5 12 f3 f4, as published in Sunny South in 1887.

Below is the photograph which accompanied Shinkman’s tribute:

Charles Henry Wheeler

(3679)

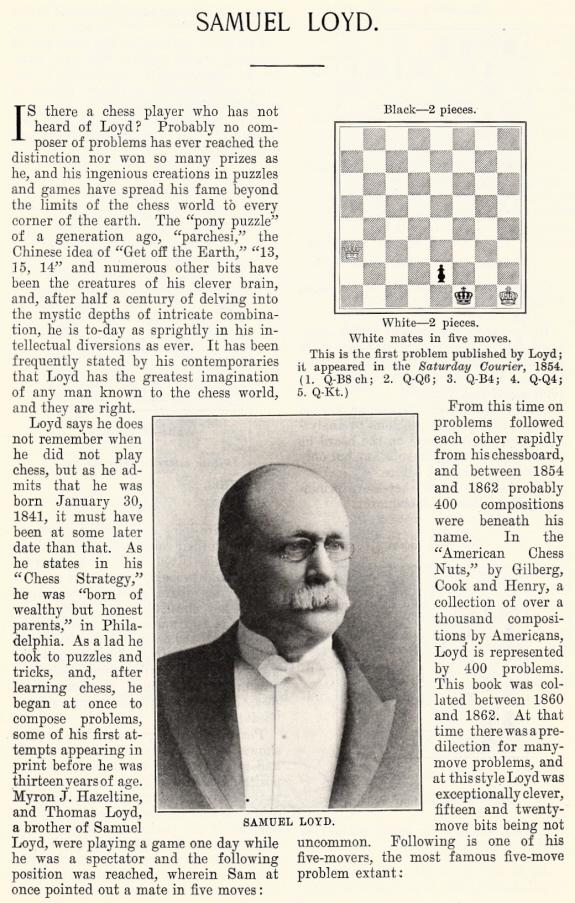

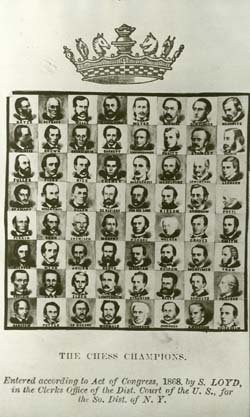

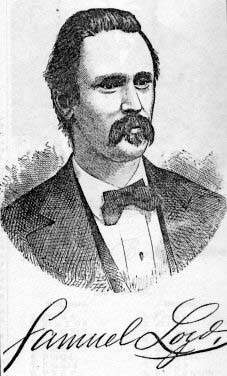

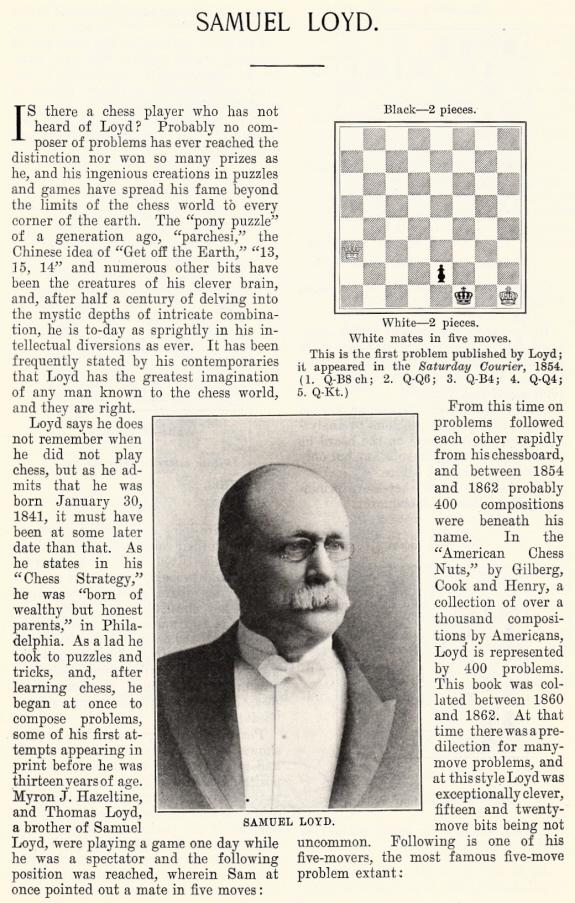

Jerry Slocum (Beverly Hills, CA, USA), who is working on a book about the 14-15 Puzzle, asks about the origins of the Sam Loyd sketch given in C.N. 3458:

We took it from page 193 of the March 1892 issue of the Chess Monthly, which did not indicate whether or not it was drawn by Loyd himself. However, it is evidently based on a photograph of Loyd which was later reproduced in, for instance, a montage on page 75 of the American Chess Magazine, July 1897:

(3618)

From Jerry Slocum:

‘Sam Loyd did not invent the 15 Puzzle (or the 14-15 Puzzle) and had nothing to do with promoting or popularizing it. This is one of the surprising findings in a new book, The 15 Puzzle, which I have written with Dic Sonneveld. It describes and illustrates the true story of the invention, patent application and manufacturing of the puzzle.

A huge puzzle craze was created by the 15 Puzzle which began in January 1880 in the USA and in April in Europe. The craze ended by July 1880, and Sam Loyd’s first article about the puzzle was not published until 16 years later, in January 1896. Loyd first claimed in 1891 that he invented the puzzle, and he continued until his death a 20-year campaign to take false credit for the puzzle. Loyd also falsely claimed that he invented the game Parcheesi and a dexterity puzzle named “Pigs-in-Clover” that generated another puzzle craze in 1889.

The actual inventor of the 15 Puzzle was Noyes Palmer Chapman, the postmaster of Canastota, New York, and he applied for a patent in March 1880.’

Our correspondent’s book can be acquired direct from him online, inscribed if so wished.

(4406)

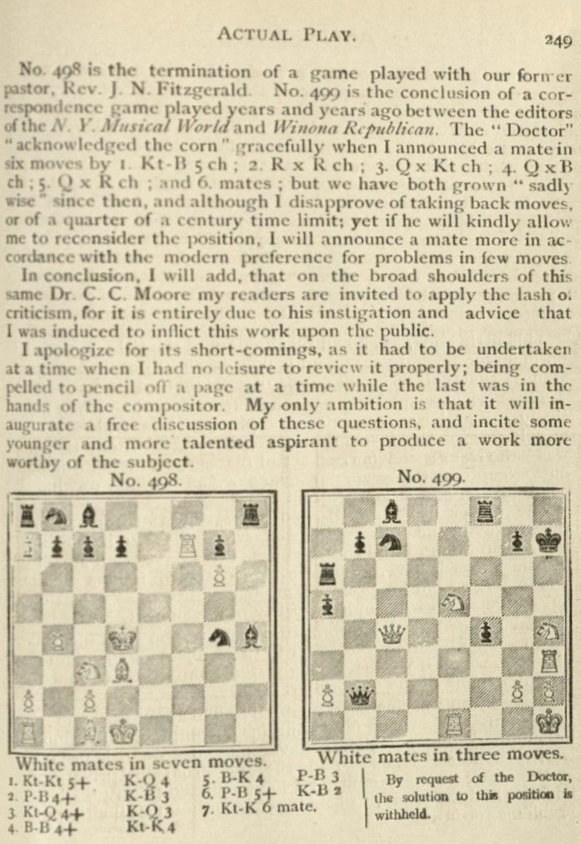

The following item by G. Koltanowski on page 83 of the December 1969 Chess Digest Magazine comes to mind:

‘White to play and mate in three moves. The author of the problem wrote “... a horrible looking think [sic], which was set up to be difficult and not elegant ...” It was shown to the Masters participating at the New York International Tournament of 1893. It took Dr E. Lasker, champion of the World at that time, 35 minutes to solve. Pillsbury took 40 minutes. The others were way off.’

Quickly passing over Koltanowski’s customary inaccuracy (in 1893 Lasker was not world champion), we note that he did not name the composer. As Michael McDowell mentions to us, the problem is number 247 in A.C. White’s Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913). Pages 200-201 identify it with the caption ‘Manhattan Chess Club, 1893’ and quote Loyd:

‘No. 247 is a horrible looking affair designed for a State Solving Contest. It was evidently posed for difficulty and not for elegance.’

What was the source of Koltanowski’s assertion about the (surprisingly long) time taken by Lasker and Pillsbury to solve the problem?

(3751)

Michael McDowell sends the following problem by H.E. Bird, from Loyd’s column in the Scientific American Supplement, 20 October 1877 (page 1502):

Mate in four

Regarding Bird, Loyd wrote in the same column:

‘... [we] cannot close without adding our tribute to his skill as a composer of chess problems of great beauty and merit ... and are particularly pleased to find a player like Mr Bird, who has encountered the champions from almost every clime, gives it as his candid opinion that he has never known a good problemist who was not a fine chessplayer.’

Below is the sketch by Loyd which accompanied the tribute:

Henry Edward Bird

(3862)

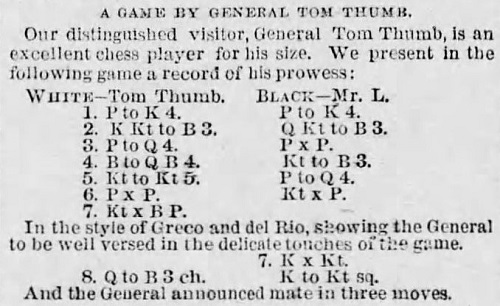

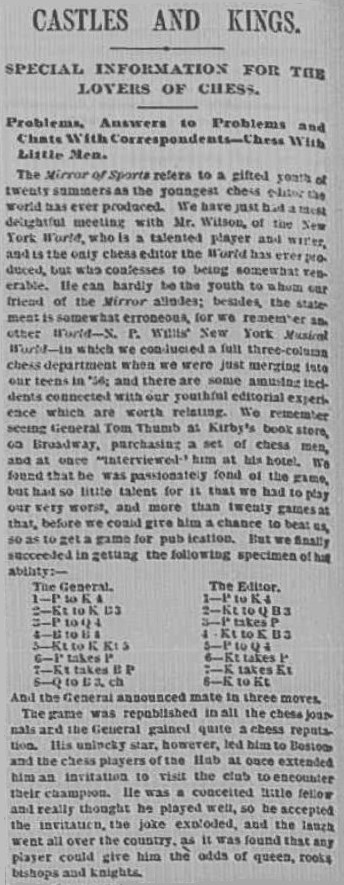

Is reliable documentation available about any involvement with chess by General Tom Thumb – i.e. Charles Sherwood Stratton (1838-83). The only nineteenth-century reference we currently have to hand is on page 216 of Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by Miron J. Hazeltine (New York, 1866), which gave the game 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 Ng5 d5 6 exd5 Nxd5 7 Nxf7 Kxf7 8 Qf3+ Kg8 and ‘White announces mate in three moves’. The heading was ‘A Mate by General Tom Thumb (At least S. Loyd says it was.)’, and Loyd was named as the General’s victim.

Where had Loyd, or anyone else, published the game beforehand?

(3931)

Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) mentions that the game appeared on page 132 of The Philadelphia Times Column of G. Reichhelm, 1879-1894, published by Caissa Editions, Yorklyn circa 1984:

‘General Tom Thumb according to the Editor of the News is an excellent chess player for his size. The first game, the only one recorded between the General and the Editor, was as follows: TT (White) – Editor (Black) 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 Ng5 d5 6 exd5 Nxd5 7 Nxf7 Kxf7 8 Qf3+ Kg8 and the General announced a mate in three.’

Our correspondent notes that the column is undated, which makes it particularly difficult to identify ‘the Editor of the News’.

(4323)

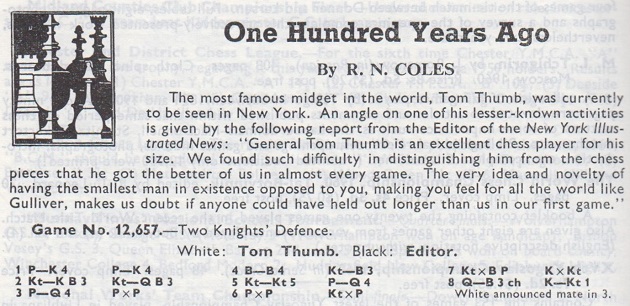

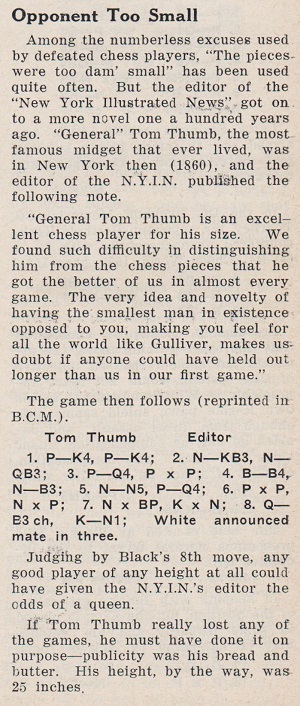

C.N. 4323 mentioned a vague reference to ‘the Editor of the News’ in connection with a game ascribed to Tom Thumb. The publication was the New York Illustrated News (whose chess columnist in 1860 was Sam Loyd), as shown by R.N. Coles on page 200 of the July 1960 BCM:

The item was picked up by Chess World, July 1960, page 127:

Can the New York Illustrated News feature about Tom Thumb be found?

(9963)

The game’s appearance on page 7 of the Philadelphia Times, 8 October 1882:

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) draws attention to background information written by Sam Loyd in his column on page 6 of the New York Evening Telegram, 3 July 1885:

Loyd’s comments about his early start as a columnist are relevant to our feature article The Caissa-Morphy Puzzle.

(9973)

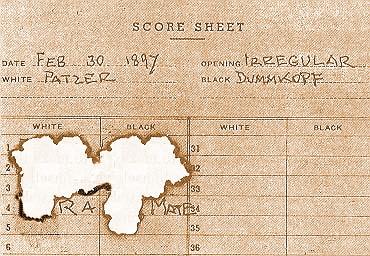

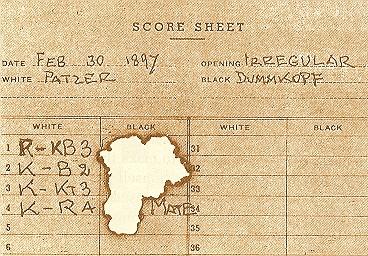

C.N. 4075 asked whether the Patzer, who had moved only one pawn and was mortified by his quick defeat, had burned his score-sheet enough to disguise how he was mated. The answer is yes.

From the second (‘less burnt’) version given in C.N. 4084 ...

... it can be ascertained that the game went 1 f3 e6 (or e5) 2 Kf2 Qf6 3 Kg3 Qxf3+ 4 Kh4 Be7 mate. However, with the two burns there are also such possibilities as 1 Nc3 e6 (or e5) 2 Na4 Bc5 3 Nb6 Qf6 4 h4 Qxf2 (or Bxf2) mate and (as pointed out by Wijnand Engelkes, Zeist, the Netherlands) 1 Nc3 e6 (or e5) 2 Rb1 Qf6 3 a3 Bc5 4 Na4 Qxf2 (Bxf2) mate.

The first illustration above is our own concoction from the second one, the latter having been published on pages 347-348 of The Colossal Book of Short Puzzles and Problems by Martin Gardner (New York, 2006). The task in the book was to reconstruct the game. No source for the problem was given, except that its contributor, Randolph W. Banner, ‘thinks he saw it in an English periodical published about 1920’.

We have yet to look into that suggestion, although it may be recalled that a fatal king dash featured in the solution to a famous Sam Loyd puzzle: ‘Find how discovered checkmate can be effected in four moves.’ See page 58 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913).

Martin Gardner’s book has a chapter on chess problems (pages 339-364), most of them quite well known.

(4093)

From C.N. 4141:

In the realm of problem composition Lord Dunsany showed much ingenuity. In the following passage from page 64 of While the Sirens Slept (London, circa 1945) he discusses his approach to creating problems:

‘And while I am on the subject of chess I may say that now and then during the years of which I have been writing I made a chess problem and used to send them to Mr E. Tinsley, for many years the chess editor of The Times Literary Supplement, whose cheery presence was never absent from any important match in or near London. I followed some principles in these problems which will be readily understood even by those who do not play chess. My first principle was that it should look childishly easy, my next, but still more important, was that an examination of it should make it appear entirely impossible, and then if I could add a little humour to the situation I was content. All puzzles may be approached in this manner. A good many of the problems that I sent to Mr Tinsley and that he reproduced in The Times Literary Supplement were “White to play and mate in one move”, fulfilling the first two conditions that I have mentioned, and that it could be done at all under these conditions perhaps fulfilled the third. The following brief sentence is only for chessplayers: one day I invented a new theme in a castling problem, and how very new it was will be appreciated by chessplayers, though perhaps scarcely believed by them, when I say that it was even new to Mr T.R. Dawson. A couple of years later than the year of which I now tell I collected some of these and (hoping that their published solutions would have been forgotten) offered a prize of half a dozen snipe to any members of the Kentish Chess Association who would solve them, for I have always felt that a president should do a little more to justify himself than merely to ornament notepaper; and I tried to amuse the members of the principal Dublin chess club in the same way. What the builder of the labyrinth in Crete was to men’s feet Mr Hubert Phillips is today to their thoughts, and among his intricacies he has printed six of these problems in his Week-end Problems Book, published in 1932. Mine also was the puzzle in that book about how to build a square house with its walls all facing south; as well as something about Big Ben. My problems appeared there in great company, for they follow one of Sam Loyd’s, the American problemist, who might well be called the leader of all whose avocation was to puzzle mankind, in comparison with whose chess problems and other puzzles, to tell what Hitler is going to do next is merely a childish exercise.’

C.N.s 3389 and 3411 (see pages 305-306 of Chess Facts and Fables) discussed a letter to the editor on pages 124-126 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, January 1905, which purported to contain reminiscences of Morphy under the pseudonym ‘Caissa’. At the conclusion of C.N. 3389 we observed that if all the personal statements in the article were correct, the writer (still alive in late 1904/early 1905) was born circa 1843, was already running a chess column in about 1858 and gave up chess some two years later.

We could, and can, think of no-one who fits the bill, but if the personal statements were not all correct Sam Loyd reverts to being a prime suspect. His track-record of dishonesty over his achievements is underscored by the fascinating book mentioned in C.N. 4406, The 15 Puzzle by Jerry Slocum and Dic Sonneveld (Beverly Hills, 2006). From page 75:

‘Sam Loyd has been correctly described as “America’s Greatest Puzzlist”, by Martin Gardner and many other writers. Although he deserves credit for his many wonderful puzzle inventions, he also had a reputation for using puzzles invented by Henry Dudeney, “England’s Greatest Puzzlist”, without crediting Dudeney, and taking credit for puzzles he did not invent. Loyd used his remarkable talent for making up stories about his puzzles to make his puzzles interesting as well as to spin tales about his accomplishments.’

Another example is on page 79:

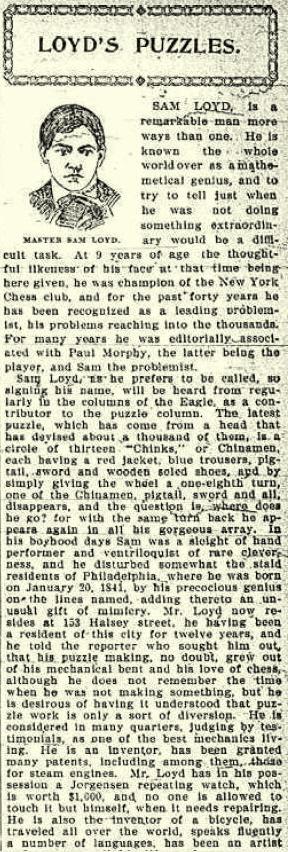

‘Sam Loyd’s first puzzle column for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle was published on 22 March 1896 with a biography of himself. He began by claiming that “At nine years of age, he was champion of the New York Chess Club”.’

(4749)

The newspaper column is shown in C.N. 7299 below. See too The Caissa-Morphy Puzzle.

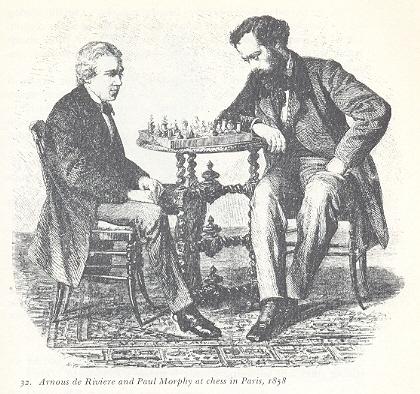

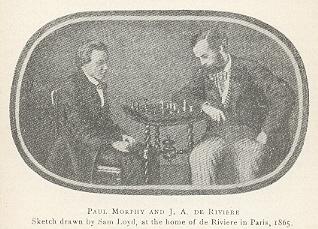

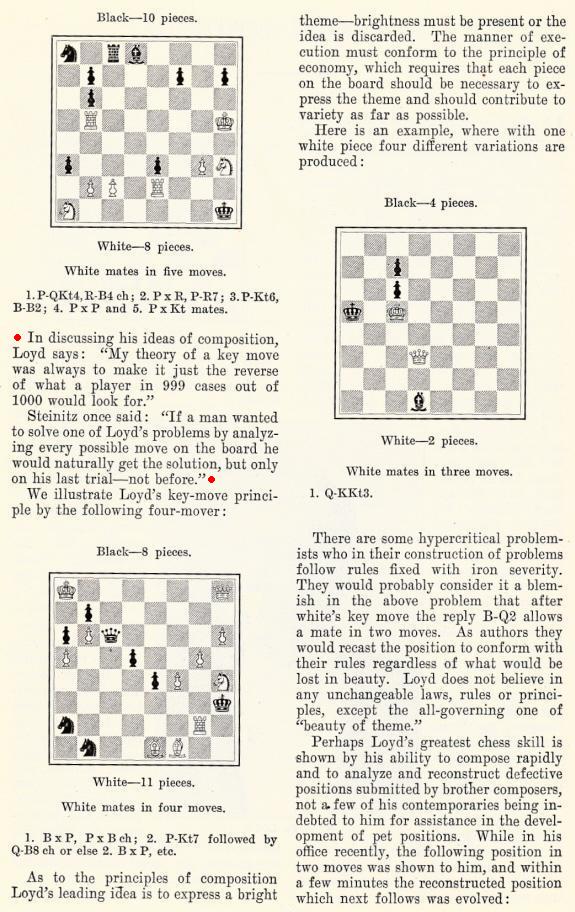

It is not easy to reconcile the captions to the following two illustrations, which appeared respectively on page 159 of David Lawson’s biography of Morphy and on page 173 of “Our Folder” (the Good Companion Chess Problem Club), 1 May 1921:

‘Arnous de Rivière and Paul Morphy at chess in Paris, 1858’

‘Paul Morphy and J.A. de Rivière.

Sketch drawn by Sam Loyd, at the home of de Rivière in Paris,

1865’

One extra complication is the question of whether ‘1865’ was a misprint for 1863.

(4165)

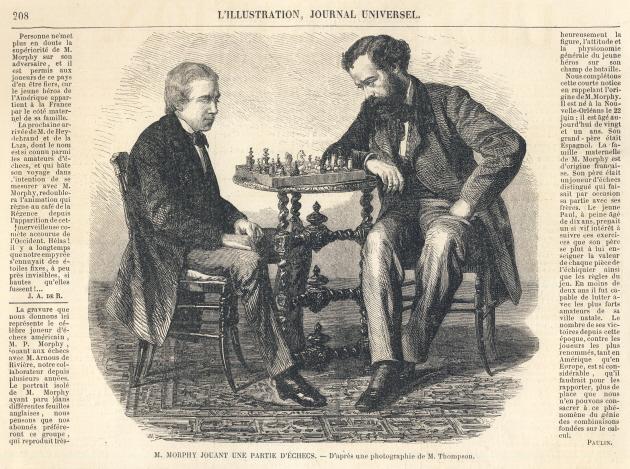

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has recently acquired this publication of the Morphy v de Rivière picture (‘d’après une photographie de M. Thompson’), on page 208 of L’Illustration, journal universel:

The exact date of the publication appears to be 25 September 1858.

(7604)

In his well-known article ‘Chess Reclaims a Devotee’ (see C.N. 3484) Alfred Kreymborg wrote:

‘In chess, the Rosens bloom on and on. In the old days, over on Second Avenue, the crack players numbered Rosen, Rosenbaum, Rosenfeld, Rosenthal, Rosenzweig – the last truly a twig compared with the others.’

Indeed, there were even two players named H. Rosenfeld – Hector and Herbert – and it is the former who interests us here. His obituary on page 169 of the December 1935 American Chess Bulletin included the following:

‘One of the best informed and most respected amateurs in the east, he was brother of the late Sidney Rosenfeld, well-known playwright, who in his day was a familiar figure at the [Manhattan Chess] Club.

Hector Rosenfeld came to New York as a young man from Virginia and was in the manufacturing business until he took up puzzle-making, in which connection he was known as “Hector” for the past 30 years. For a while he was an associate of the junior, Sam Loyd, whose father had a worldwide reputation as “King of Chess Problem Composers”. Mr Rosenfeld was a member of the National Puzzlers’ League and the Riddlers, its New York City branch.’

His obituary on page 24 of the January 1936 Chess Review added the following information:

‘He founded the Riddlers, a New York puzzle club, contributed to Enigma, and was at one time Puzzle Editor of the Ladies’ Home Journal. It is estimated that he composed more than 10,000 puzzles, charades, transposals, anagrams, crosswords, acrostics and other types, which he syndicated through 40 newspapers under the name of “Hector”. Through his interest in puzzles he became acquainted with Sam Loyd and contributed an article about the famous “King of Chess Problem Composers” which was published in our July 1935 issue.’

Many previous C.N. items (see the Factfinder) have discussed the puzzles of Sam Loyd, Hubert Phillips and H.E. Dudeney, and we should like to find out more about Hector Rosenfeld (1857-1935).

(4923)

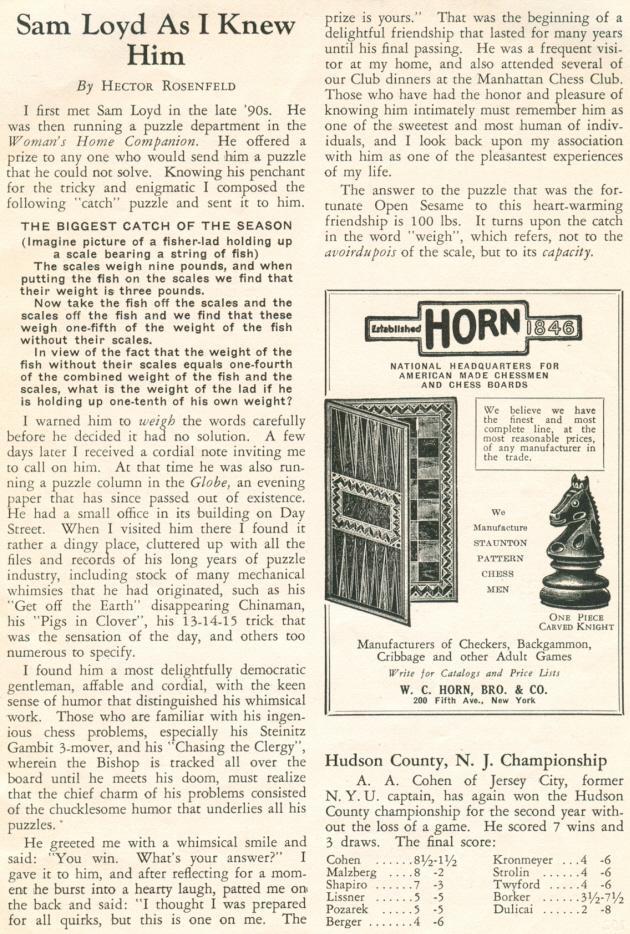

Concerning Hector Rosenfeld we add the article ‘Sam Loyd As I Knew Him’ from page 151 of the July 1935 issue of Chess Review:

(7043)

From C.N. 5456:

Miron James Hazeltine

Below is part of Samuel Loyd’s assessment of Hazeltine on page 1630 of the Scientific American Supplement, 15 December 1877:

‘In fact, an extended notice of our old friend would almost necessitate an autobiography of ourself, for our earliest recollections of the game are associated with his pleasant instructions at the odds of a queen, and the boyish pride we felt when he finally passed upon our first problem as worthy of publication. Our old intimacy has survived the various degrees of reduced odds, until the question of strength would be decided a shade in our favor, and the master submitted problematical questions to the judgment of the pupil.

Mr Hazeltine is most lavish in his admiration for the work of others, but has never essayed to compose a problem nor to acquire fame as a player; he has been satisfied to earn for himself the widespread reputation of an honest, liberal and enthusiastic worker for the cause of chess, who is beloved by the entire fraternity.’

Loyd’s sketch of Hazeltine in the Scientific American Supplement

This sketch of John Cochrane by Samuel Loyd, based on a picture in the Westminster Papers, was published on page 1964 of the Scientific American Supplement, 11 May 1878:

(5590)

See also the illustrations by Loyd (of Frank Norton and Harry Boardman) shown in Nineteenth-century Chess Prodigies.

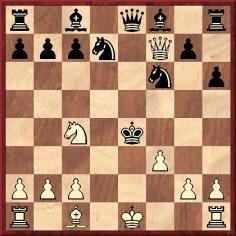

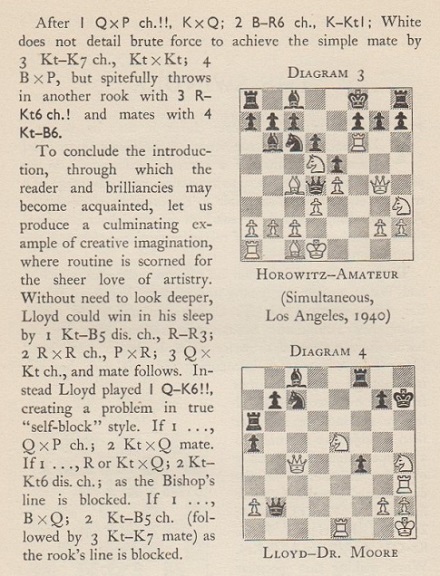

C.N. 5647 gave an extract from The Pleasures of Chess by Assiac (New York, 1952):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nd7 4 Bc4 h6 5 dxe5 dxe5 6 Bxf7+ Kxf7 7 Nxe5+ Kf6 8 Qf3+ Kxe5 9 Qf7 Ngf6 10 Nd2 Qe8 11 Nc4+ Kxe4 12 f3+

12...Kf5+ 13 Ne3+ Ke5 14 Nc4+ Kf5+ Drawn.

We have still found no other games which finished with, in Assiac’s term, ‘double-perpetual’.

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) recalls a passage from page 153 of Pollock Memories by F.F. Rowland (Dublin, 1899). The writer is Pollock.

‘But I should like to see a position which Mr Loyd told me he had constructed some years ago – or, at least, was constructing. It was a sort of problem in which both kings were in perpetual check, and neither could escape, nor could either side either win or lose the game. He called it “The Whirlpool”.’

Our correspondent asks whether more is known about Loyd’s construction.

Michael McDowell points out to us that the Pollock passage was quoted at the start of an article ‘Consecutive Checks Task’ by John Roycroft on pages 56-57 of the July-September 1976 issue of The Problemist. It seems that no information about a Loyd ‘whirlpool’ composition has been found, but on a similar theme we pick from Mr Roycroft’s rich article a study by E.B. Cook published in the Illustrated London News of 7 June 1856:

White to move and draw

Solution: 1 Bf7+ Kg4 2 Be6+ Kf4 3 Rf5+ Kg4+ 4 Re5+ Kf4 5 Rf5+.

(5957)

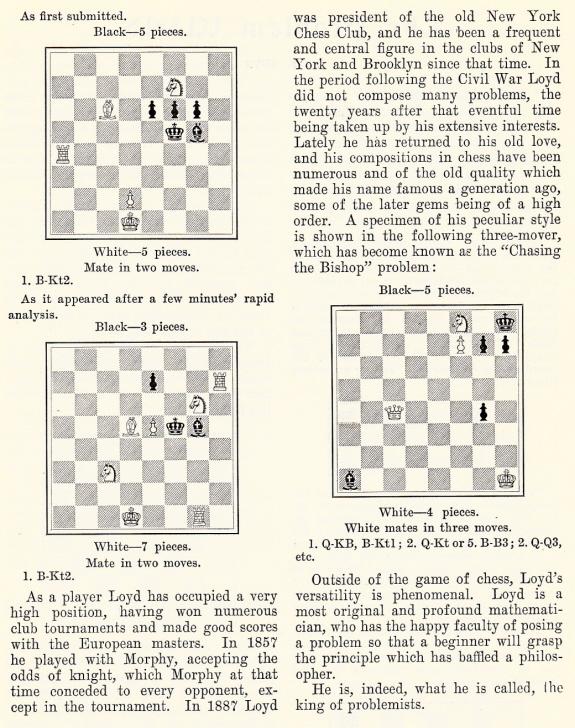

Below is a sketch of G.H. Mackenzie by Samuel Loyd, published in the Scientific American Supplement, 4 May 1878, page 1948:

(5785)

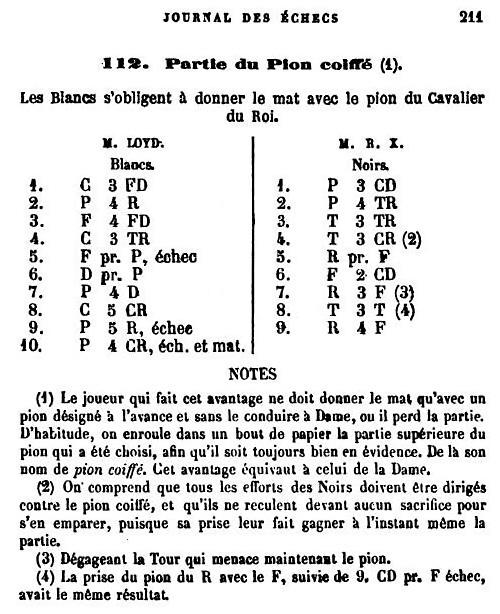

From Dominique Thimognier (St Cyr sur Loire, France) comes this game on page 211 of Le Sphinx Journal des Echecs, 1866:

1 Nc3 b6 2 e4 h5 3 Bc4 Rh6 4 Nh3 Rg6 5 Bxf7+ Kxf7 6 Qxh5 Bb7 7 d4 Kf6 8 Ng5 Rh6 9 e5+ Kf5 10 g4 mate. Information on the identity of the players is sought.

Michael McDowell notes that page 458 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913) had the conclusion of a capped-pawn game between the Loyd brothers. Below is the full score, from pages 207-208 of the Chess Monthly, June 1857:

Thomas Loyd – Samuel Loyd

Occasion?

(White’s g-pawn is capped)

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 d5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Bf4 Nf6 4 a3 Bf5 5 e3 e6 6 Bd3 Ne7 7 Nb5 Bxd3 8 Nxc7+ Kd7 9 cxd3 Ng6 10 Qa4+ Kc8 11 Rc1 Nh4 12 Nxe6+ Qc7 13 Rxc7+ Kb8

14 Rxf7+ Kc8 15 Rc7+ Kb8 16 Rxg7+ Kc8 17 Rc7+ Kb8 18 Rxh7+ Kc8 19 Rxh4 Rxh4 20 Nxf8 Kd8 21 Be5 Nh7 22 Nxh7 Rxh7 23 Bd6 Rc8 24 Qb5 Rh5 25 Qxb7 Rxh2 26 Rxh2 Rc1+ 27 Kd2 Rxg1 and White gave mate in 11 moves.

This is the position in the above-mentioned Loyd book, which (whilst noting that ‘there are many duals and short mates in the variations’) gave the following as a mate in 11: 28 Qc7+ Ke8 29 Qc8+ Kf7 30 Rh7+ Kf6 31 Be5+ Kg5 32 Qg8+ Kf5 33 e4+ dxe4 34 Qf7+ Kg4 35 Qe6+ Kg5 36 f4+ exf3 37 Qf6+ Kg4 38 gxf3 mate.

(6093)

See also Chess Variants and Rule Changes.

An item in Steinitz’s ‘Personal and General’ column on page 114 of the April 1885 International Chess Magazine:

The unpublished list of newspaper columns compiled by H.J.R. Murray specified (item 1560) that the columnist was Sam Loyd.

(6666)

We thank Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) for pointing out the full text of the article about Samuel Loyd mentioned in The Caissa-Morphy Puzzle. It comes from page 23 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 March 1896:

(7299)

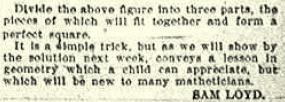

A few lines about Sam Loyd from page 186 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993):

The references ‘(34)’ and ‘(23)’ relate to entries in the ‘Bibliography’, on page 472. Thus Landsberger’s misinformation that Chess Strategy was published in 1882 (the book was dated 1878) is ascribed simply to the Deutsche Schachzeitung, without any date of issue or other particulars. Landsberger’s source for the Steinitz quote is merely Irving Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (with a mix-up over the publication details of the US and UK editions). McFarland & Co. Inc.’s decision to publish William Steinitz, Chess Champion is as bewildering as the encomiums which the back cover of the 2006 paperback edition was able to cite.

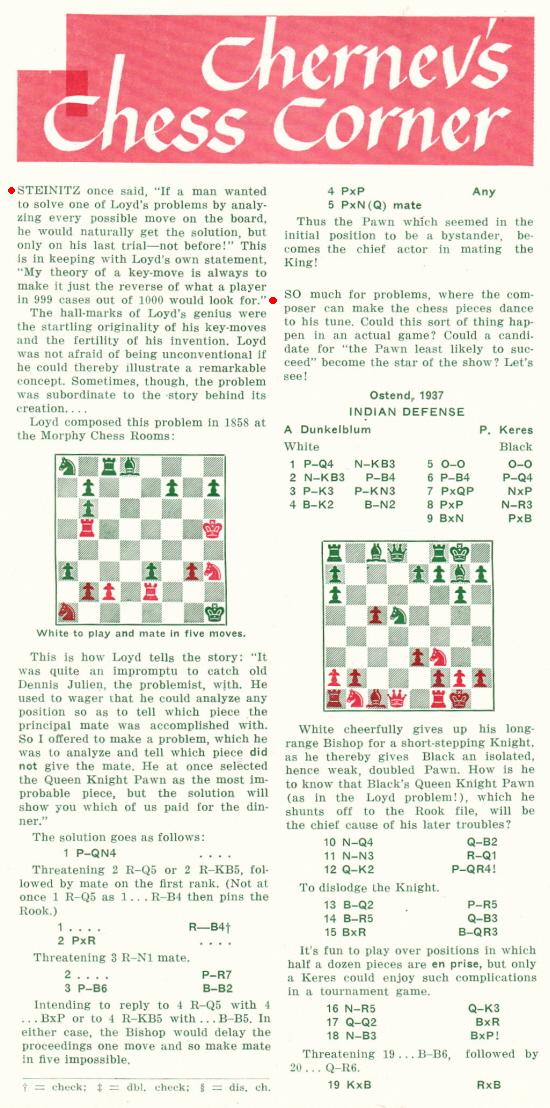

Chernev did indeed give the Steinitz quote, without a source, in The Bright Side of Chess (see page 109), and also, in a ‘once’ version, at the start of an article on the inside front cover of the May 1950 Chess Review:

The Loyd section was reproduced by Chernev on page 153 of The Chess Companion (New York, 1968).

But when did the remarks by Steinitz and by Loyd himself first appear in print? Michael McDowell notes that they were both included in an unsigned article on pages 83-85 of the December 1904 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

The mast-head named Loyd as an ‘Associate Editor’ of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, and he had a regular column (‘The Problem World’).

Is it possible to find earlier appearances in print of what ‘Steinitz once said’?

(8692)

Our article Muddled Chess Epigrams shows the following page from page 112 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948 and London, 1952):

Concerning the Loyd paragraph, we referred to Lasker’s Chess Magazine, December 1904, page 84, where the text was given as a quote by Loyd in an unsigned article about him (pages 83-85).

A selection of quotes from Chess Strategy by Samuel Loyd (Elizabeth, 1878):

‘A few years ago the problemists represented an insignificant minority, and it would have been difficult to name a dozen composers of acknowledged merit.

Today the art is assuming its proper importance in the chess world as a most fascinating feature and invaluable school of practice. Almost every player has essayed to produce a few problems, and among its votaries we find not only the leading spirits of chess journalism, and the finest players of the day, but the main supporters and contributors to every chess publication or enterprise that is undertaken.’ (page 6)

‘It is a great mistake to consider it a weakness for a problem to commence with a check. Some of the most brilliant and difficult tournament problems extant consist of a series of checks, and in many positions we will find that a check is the most unpromising move that could be made, and is therefore brilliant and difficult.’ (page 18)

‘I have devoted considerable time to cutting down my longer productions to within five moves, which I consider the extreme limit of a common sense problem. Problems in excess of this number are only excusable when there are very few pieces, and the positions are intended to illustrate some pleasing and simple trick.’ (page 37)

‘The only thing that I dislike more than a problem in over five moves is a poor one in two.’ (page 37)

‘The real merit and science of the feature of difficulty is best shown when embodied in the theme – in the actual moves made, and not in the mere perplexities of the situation. This I will explain by first laying it down as an axiom that a difficult move is one that gives the least apparent promise of the desired result. When a position contains an elegant and scientific theme, with the pieces well posed so as to give no indications of their object, the solver is compelled to form the combination in his mind, much as if he were composing a problem.’ (page 203)

‘My entire work has been devoted to an elucidation of the standpoint that beauty and merit are best defined as difficulty produced with the least possible number of pieces.’ (page 234)

‘I do not think that players who are not problemists appreciate the benefits derived from the practice of solving. It imparts a spirit of ingenuity, quickness, correctness, and a clear insight of complicated positions that can be acquired in no other way.’ (page 246)

(8813)

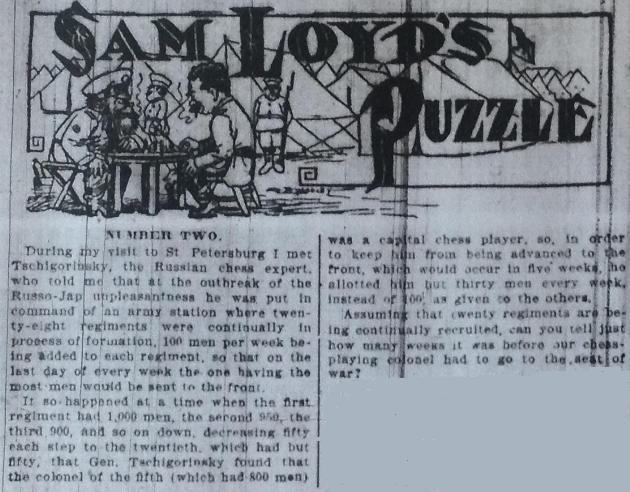

Eduardo Ramirez (Chicago, IL, USA) has found this puzzle by Sam Loyd in the Chicago Daily News, 22 November 1905:

For now, the remainder of the item (the solution) is omitted.

The puzzle was reproduced, under the title ‘The Chess Playing Colonel’, on page 27 of Mathematical Puzzles of Sam Loyd selected and edited by Martin Gardner (New York, 1959). The solution was on page 131.

(8879)

The full text of Sam Loyd’s puzzle, including the answer, from the 22 November 1905 edition of the Chicago Daily News:

(8896)

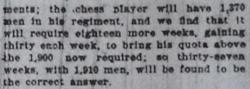

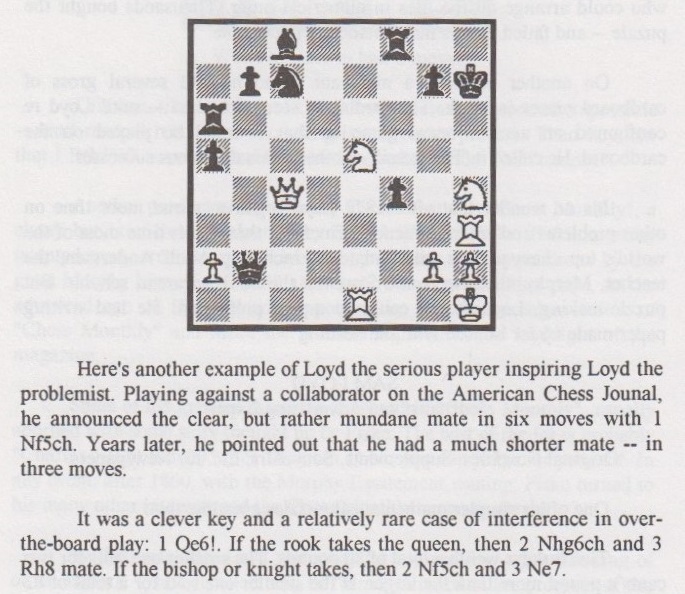

White can mate in three with 1 Qe6.

From Michael McDowell:

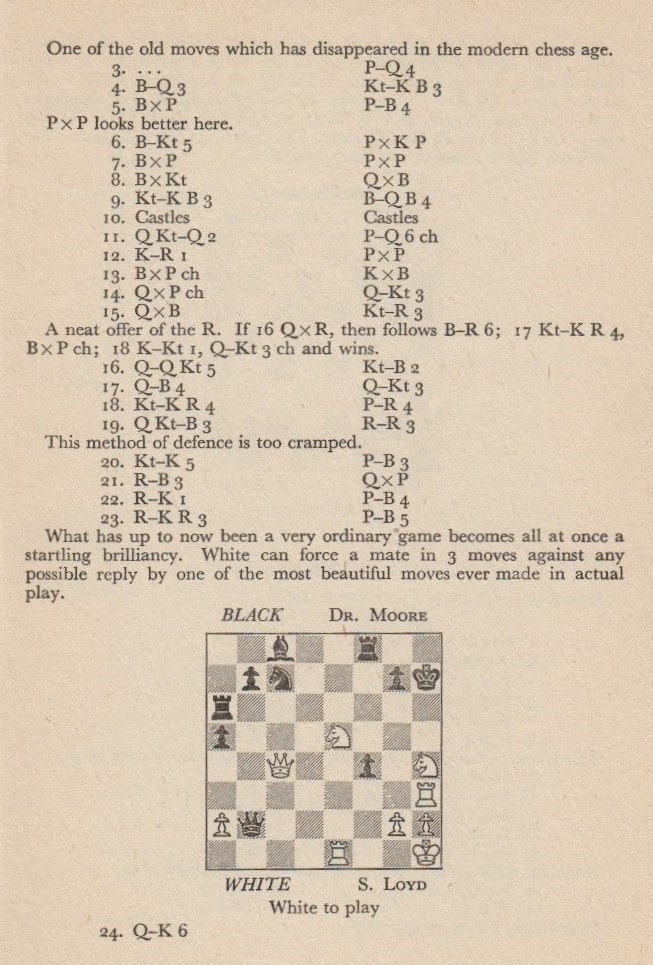

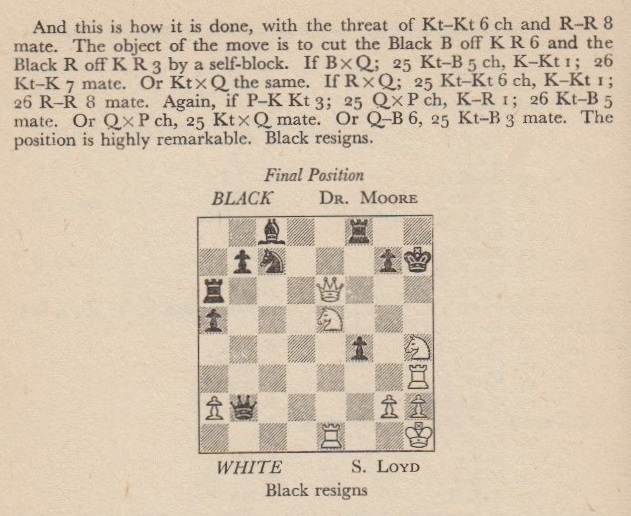

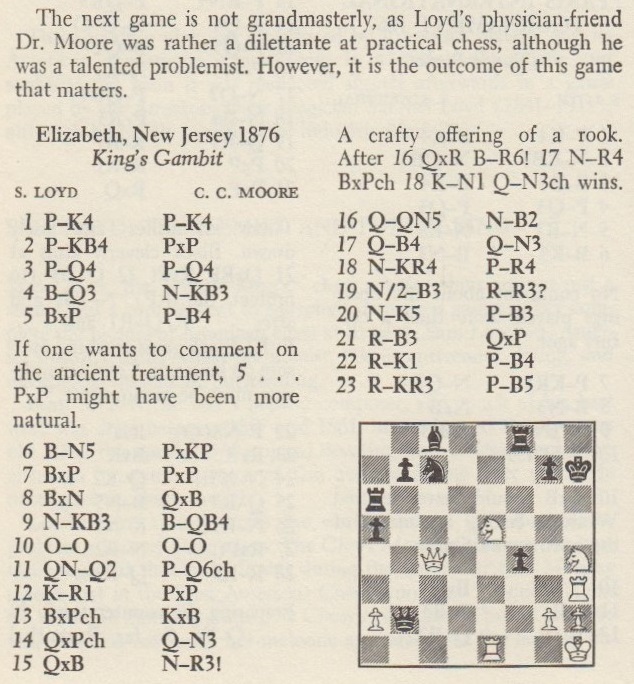

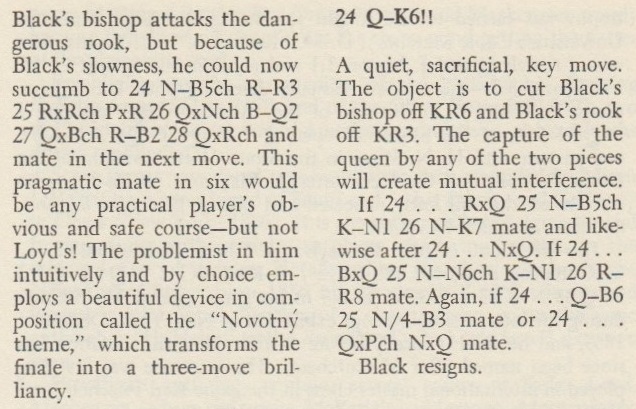

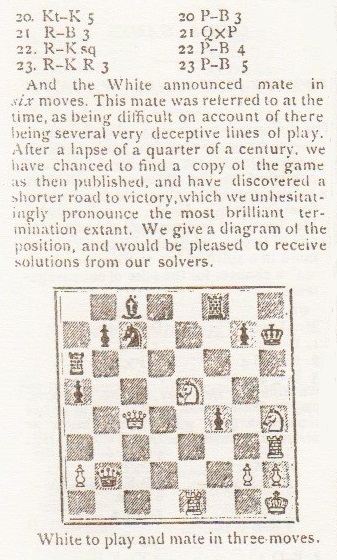

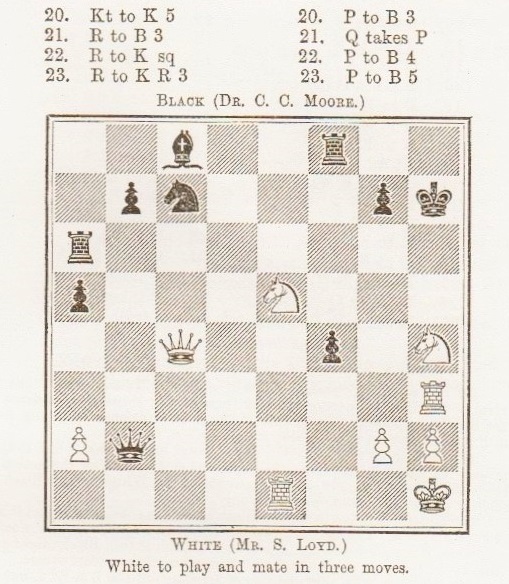

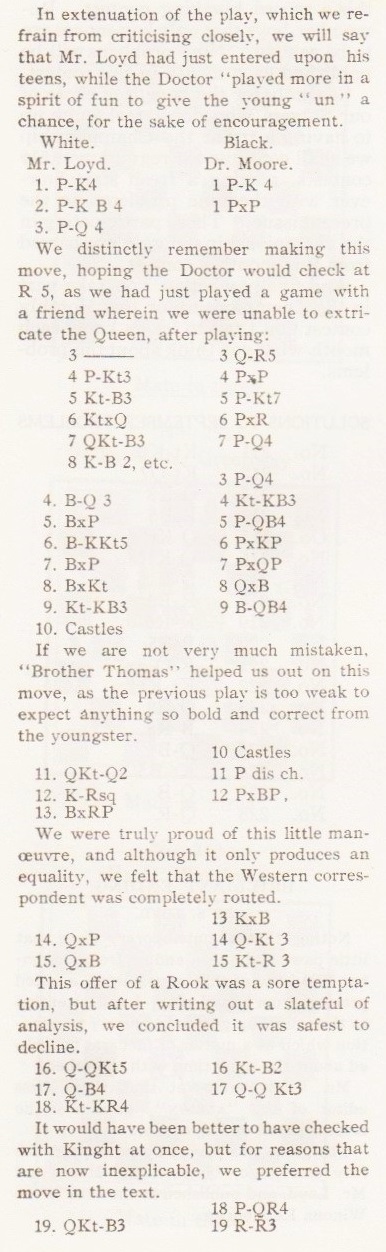

‘Concerning diagram 60 in Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems, the famous Loyd v Moore game has always struck me as suspicious. The mate in three, showing (in the problemist’s jargon) a Nowotny followed by matching battery shut-offs, seems just too perfect to have arisen by chance. I recall, though, that the game-score is in one of Wenman’s books.’

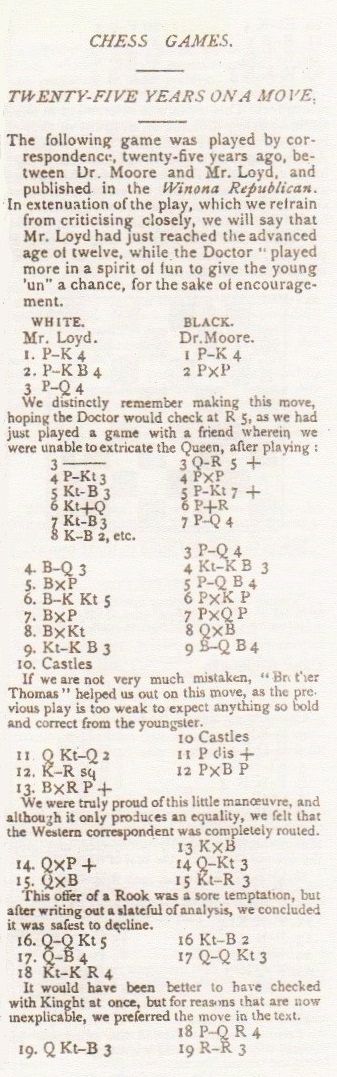

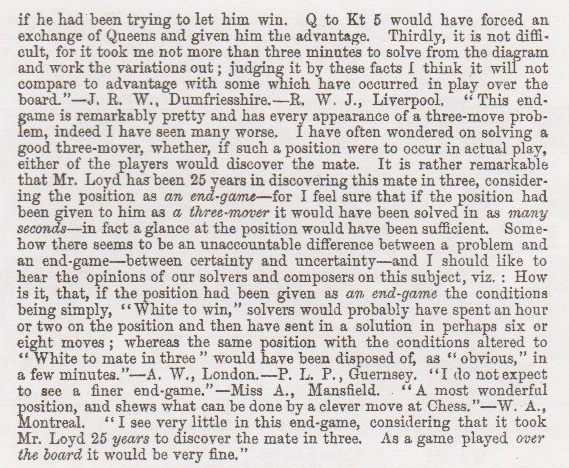

It is a tangled affair, and we begin by showing pages 56-57 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913):

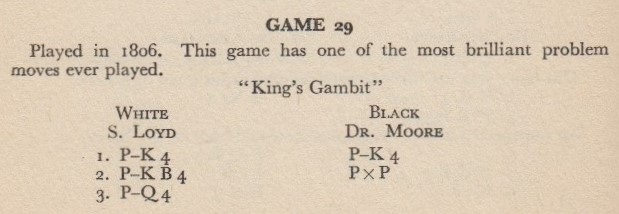

As regards Wenman, the following comes from his book One Hundred and Seventy Five Chess Brilliancies (London, 1947), the pages being unnumbered:

Wenman’s date for the game, 1806, was 35 years before Loyd was born.

Another author who discussed the game, though naming White as ‘Lloyd’, was Walter Korn, on page 3 of The Brilliant Touch (London, 1950):

Korn published the full score (‘Elizabeth, New Jersey, 1876’), with White named as Loyd, on pages 44-45 of America’s Chess Heritage (New York, 1978):

The game is also in databases, with various years from 1853 to 1906. In the May 1942 BCM, page 100, T.R. Dawson gave the finish with a diagram labelled ‘c. 1868’.

On page 10 of Sam Loyd His Story and Best Problems (Dallas, 1995) Andrew Soltis steered clear of specifics, except for the name of a nineteenth-century magazine, which he nearly spelt correctly:

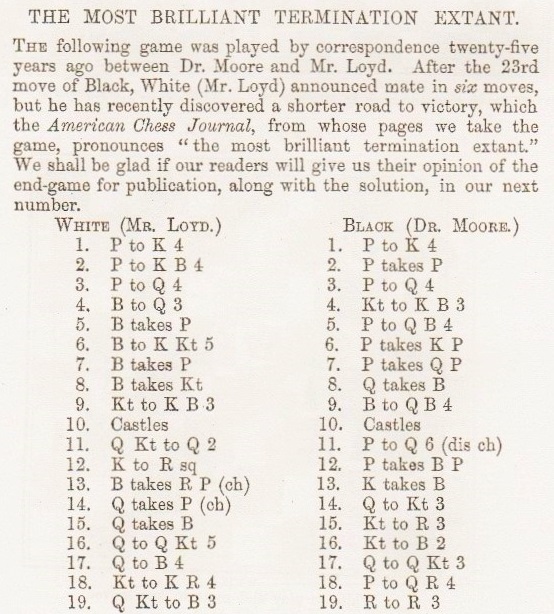

Below is the full game’s appearance on pages 194-193 [sic – the numbering of the two pages was inverted] of the November 1878 American Chess Journal:

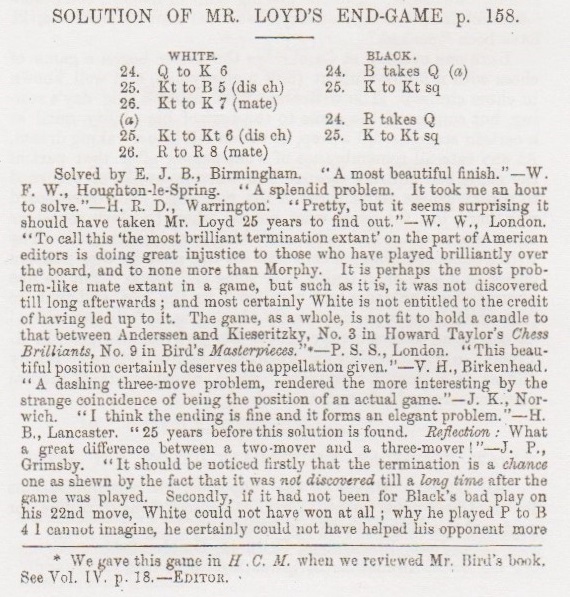

The game was subsequently published (headed with the American Chess Journal’s description ‘The most brilliant termination extant’) on pages 157-158 of the March 1879 Huddersfield College Magazine:

The opinions solicited by the magazine were presented on pages 221-222 of the May 1879 issue:

Loyd himself gave only the conclusion on page 249 of his book Chess Strategy (Elizabeth, 1878). The scan below has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library:

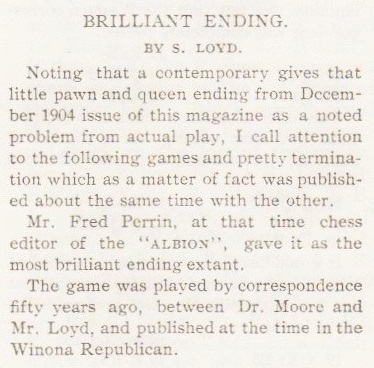

Loyd presented the full game on pages 45-46 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November 1905, and left readers to assume that he did indeed play 24 Qe6:

For the pawn and queen ending referred to in Loyd’s first paragraph, see C.N. 8692.

As regards Moore, a brief article and illustration by Loyd were published on page 1342 of the Scientific American Supplement, 11 August 1877:

Moore’s entry in Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige (Jefferson, 1987) was slightly augmented in the unpublished 1994 edition:

The earliest publication of the Loyd v Moore game or position found so far dates from 1878. Is it possible to trace earlier appearances and, in particular, to corroborate Loyd’s claim that he played the game by correspondence when he was a boy and that it was published in the Winona Republican around 1853-54?

(8945)

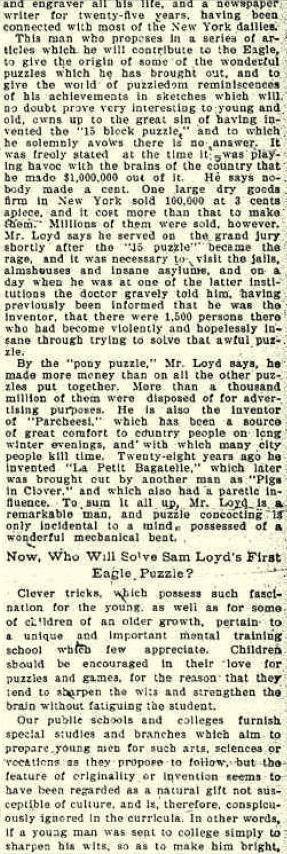

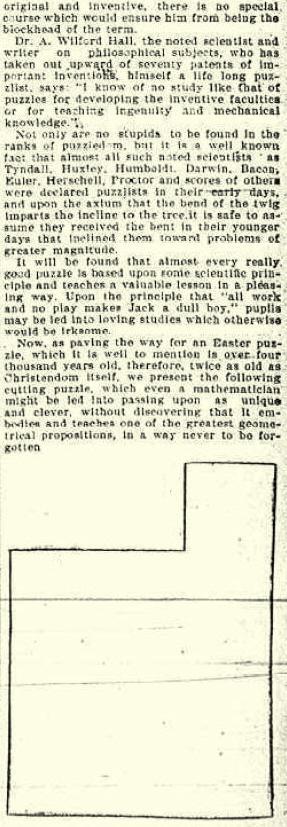

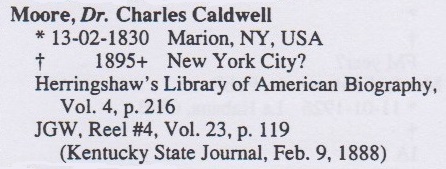

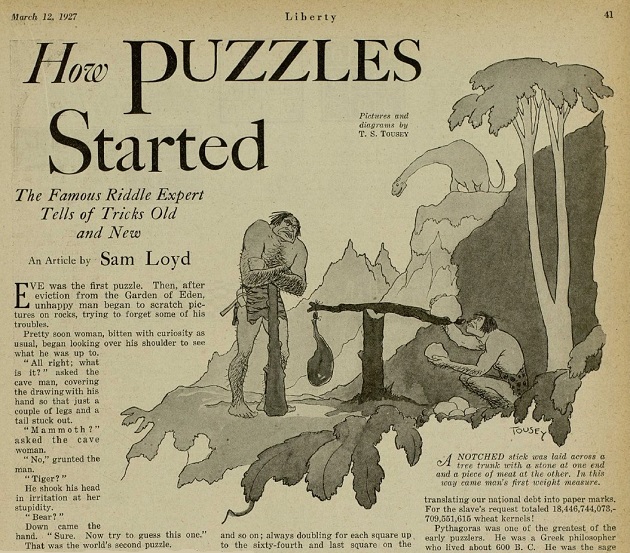

This is an extract from ‘How Puzzles Started’ by Sam Loyd, an article published on pages 41, 42 and 47 of Liberty, 12 March 1927.

The solutions will be shown in a future C.N. item. Loyd, it should be recalled, died in 1911.

(9009)

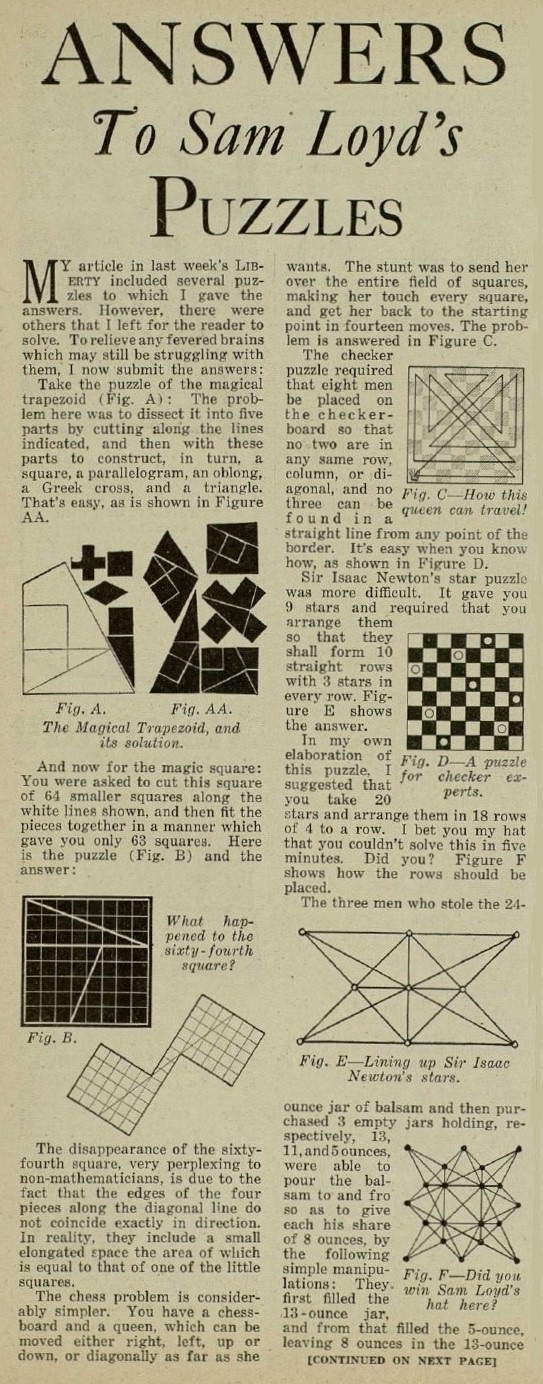

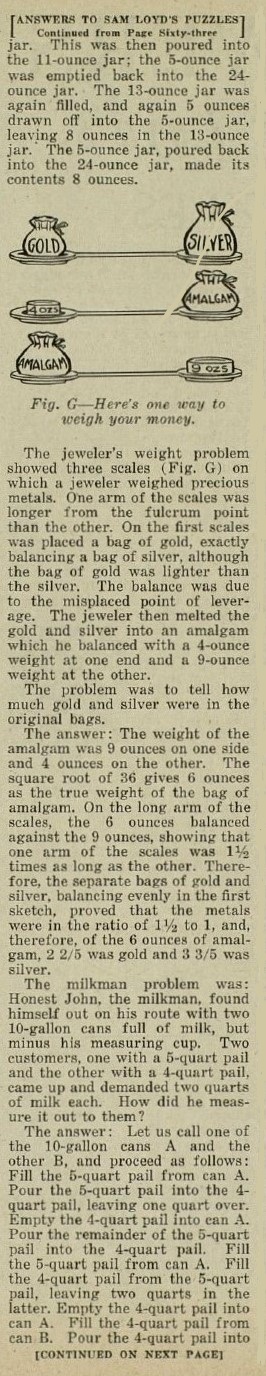

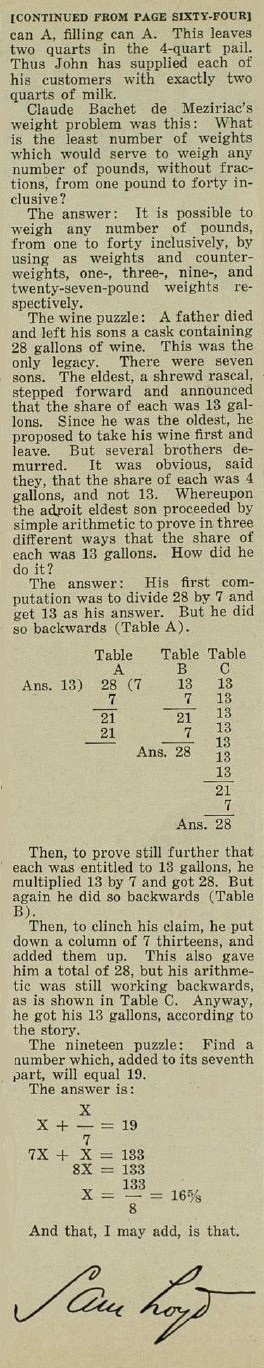

The answers published in Liberty, 19 March 1927, pages 63-65:

(9015)

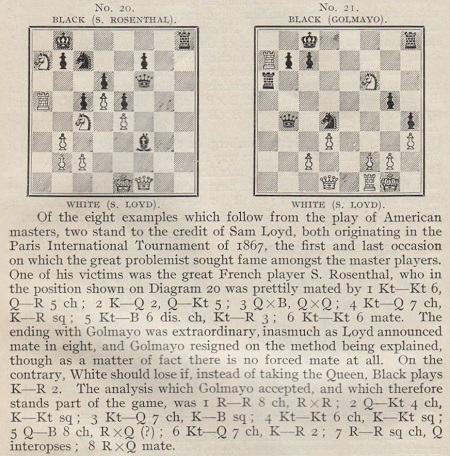

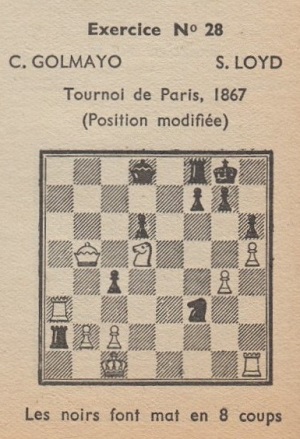

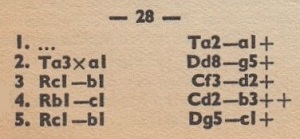

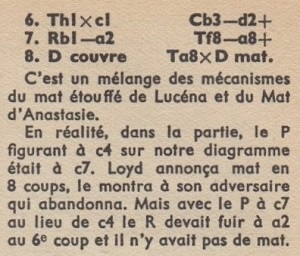

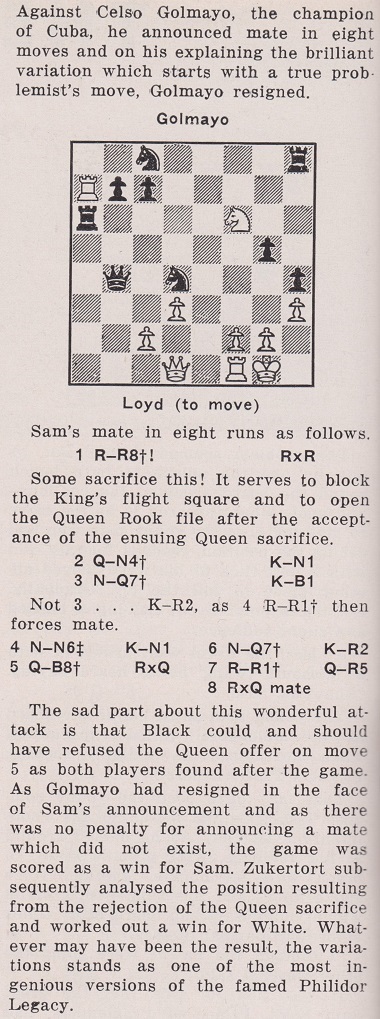

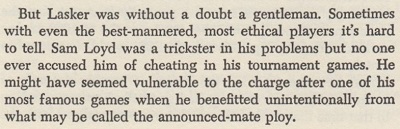

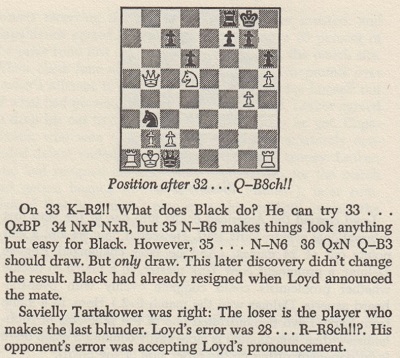

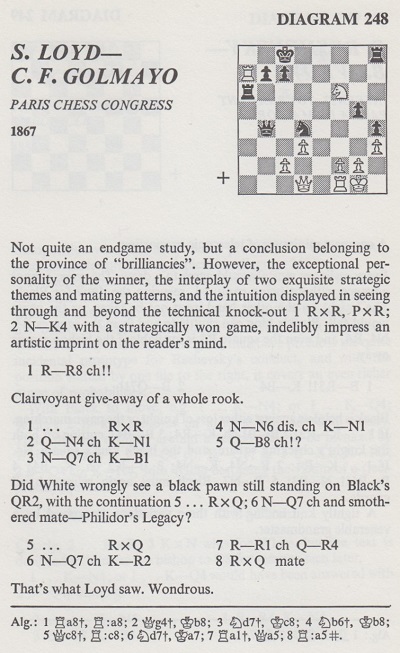

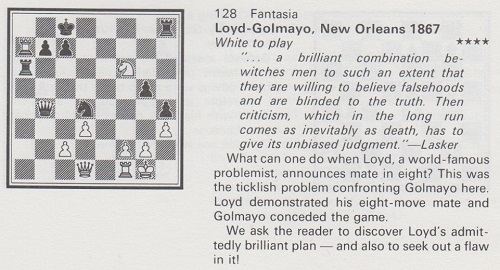

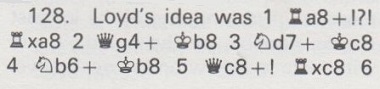

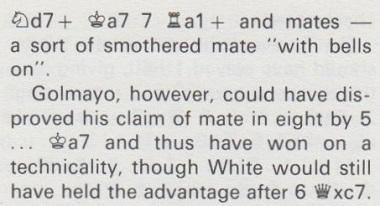

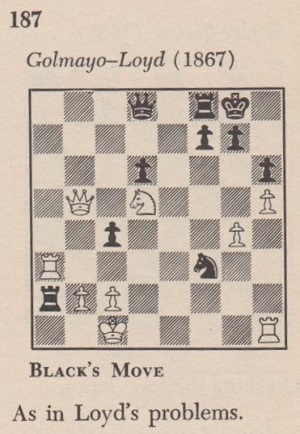

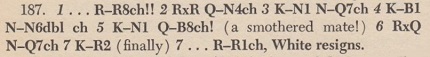

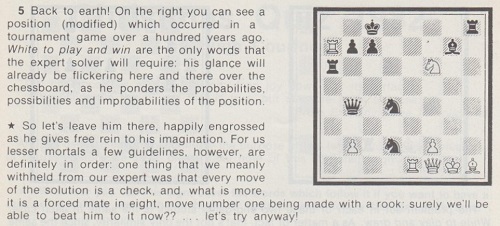

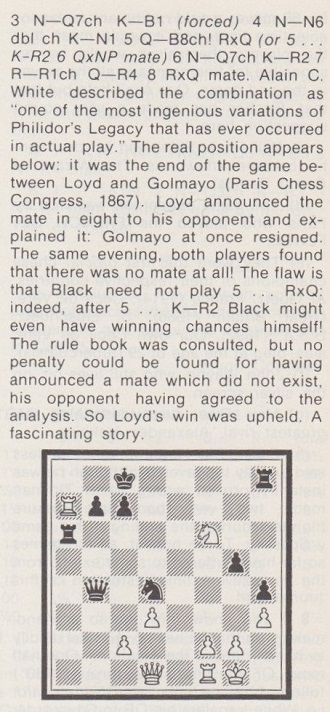

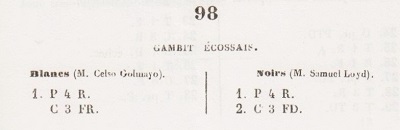

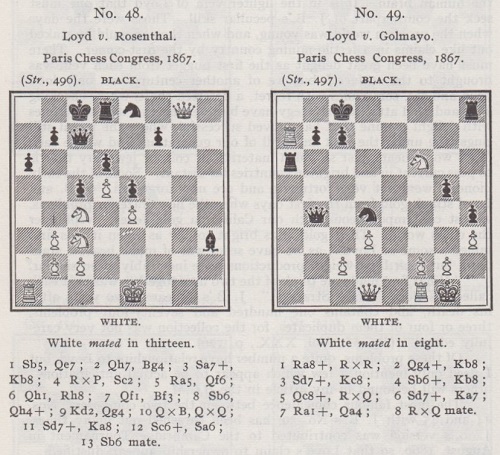

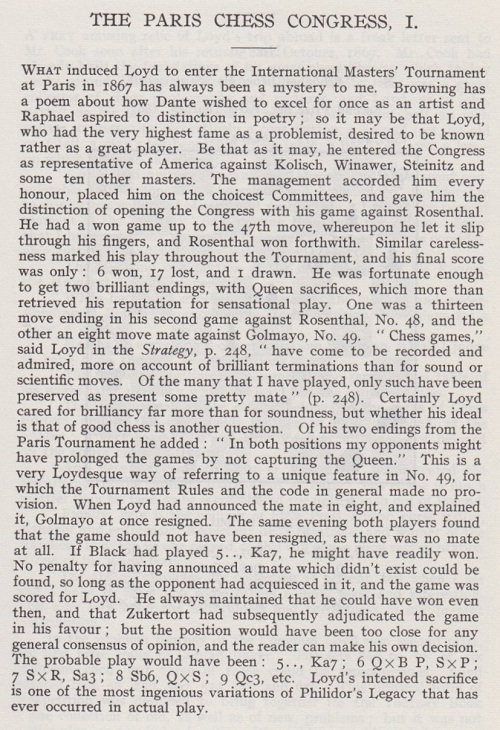

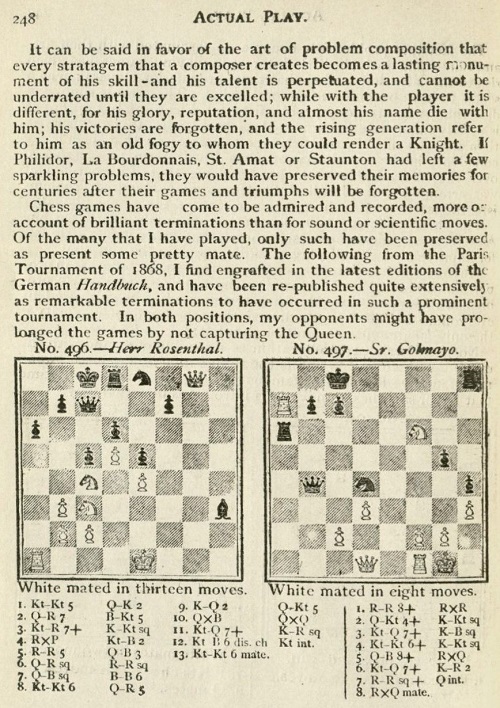

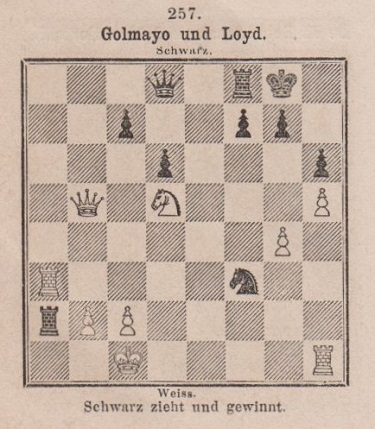

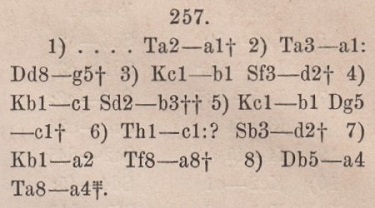

Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) asks for documentation with regard to the contradictory accounts of a famous 1867 game between Celso Golmayo and Sam Loyd.

We begin with a selection of secondary sources, presented with a minimum of comment:

The same position (but with, of course, c8 occupied by the black king) was given by Pal Benko on page 87 of the April 1967 Chess Life.

The reference to ‘S.’ Golmayo is an evident error.

It is hard to understand why New Orleans, rather than Paris, was given as the venue. The ‘brilliant combination’ quote comes from the discussion of the Evergreen Game in Lasker’s Manual of Chess, e.g. on page 303 of the New York, 1927 edition.

For analysis of the conclusion of the game (in which Loyd was Black), see pages 58-59 of Winning Chess Combinations by Yasser Seirawan (London, 2006).

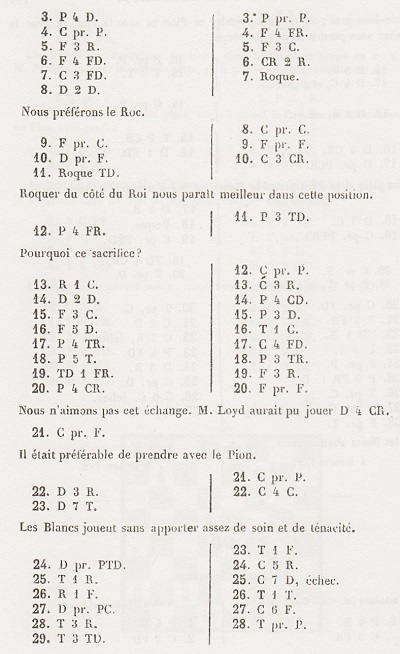

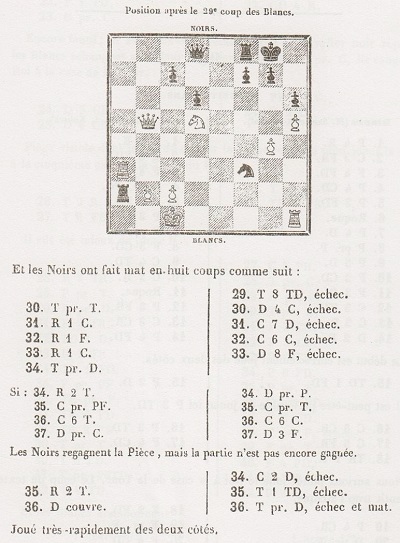

Below is the game as published on pages 191-193 of the Paris, 1867 tournament book, Congrès international des échecs (Paris, 1868):

The statement in the final note that both sides played the game very quickly is corroborated by the chart on page lxxii of the tournament book, which added that the game took place on 27 June 1867. As shown below, Loyd himself wrote that he played rapidly throughout the tournament.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Bc5 5 Be3 Bb6 6 Bc4 Nge7 7 Nc3 O-O 8 Qd2 Nxd4 9 Bxd4 Bxd4 10 Qxd4 Ng6 11 O-O-O a6 12 f4 Nxf4 13 Kb1 Ne6 14 Qd2 b5 15 Bb3 d6 16 Bd5 Rb8 17 h4 Nc5 18 h5 h6 19 Rdf1 Be6 20 g4 Bxd5 21 Nxd5 Nxe4 22 Qe3 Ng5 23 Qa7 Rc8 24 Qxa6 Ne4 25 Re1 Nd2+ 26 Kc1 Ra8 27 Qxb5 Nf3 28 Re3 Rxa2 29 Ra3 Ra1+ 30 Rxa1 Qg5+ 31 Kb1 Nd2+ 32 Kc1 Nb3+ 33 Kb1 Qc1+ 34 Rxc1 Nd2+ 35 Ka2 Ra8+ 36 Q moves R mates.

The finish was discussed in detail by Alain C. White on pages 46-47 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913):

The passage referred to by A.C. White, from Loyd’s book Chess Strategy (Elizabeth, 1878), is shown below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

Loyd also wrote about the finish in his column on page 1646 of the Scientific American Supplement, 22 December 1877:

The ‘collection’ referred to in Loyd’s column (and here too he inverted the colours) was Sammlung der auserlesensten Schach-Aufgaben Studien und Partiestellungen by J.H. Zukertort (Berlin, 1869). From pages 46 and 72:

The present item illustrates the degree of confusion that may exist in chess literature even when a game-score, as published in the tournament book, is not in dispute.

(9137)

From page 282 of Chess World, 1 December 1948:

‘Not to care for Sam Loyd’s chess problems is, in a chessplayer, simply ignorance – to know them is to like them. Even the most besotted anti-problemist must count Loyd an exception. Sam Loyd’s ingenuity was really incredible. In the puzzle world he was what Shakespeare is in literature.’

(9491)

From page 364 of the Dubuque Chess Journal, September 1875, at the end of an article on Sam Loyd:

‘Outside of the chess world, Mr S. Loyd has made himself famous by the construction of advertising puzzles, such as pictures of trick mules on moveable cards, and various ingenious toys; from which patented and copyrighted trifles he has, we understand, accumulated a comfortable living and quite a fortune.’

After referring to this on pages 263-264 of the October 1875 City of London Chess Magazine, W.N. Potter commented:

‘We are glad to hear of such being the case; brains outside of chess are, nowadays, a valuable marketable commodity. There are some enthusiasts who imagine the advent of a time when, in the limits of the game, superior intelligence will be profitable. We do not share their views. Caissa, we feel assured, will never have any niche in the Temple of Mammon, nor are we clear that this is any matter worth whining at.’

(9895)

‘I wonder whether it is a very old story – that puzzle by (I believe) J.H. Blackburne. Place the black K on one of the four central squares, and then take from the box two white rooks and one white knight. Now arrange these three white pieces so that the black K stands mated. No moves are to be made – simply place them in such a manner that the condition is fulfilled. As there are no pawns, there is necessarily more than one solution, but the principle is the same in each. If you do it in 15 minutes you will be smarter than I was.’

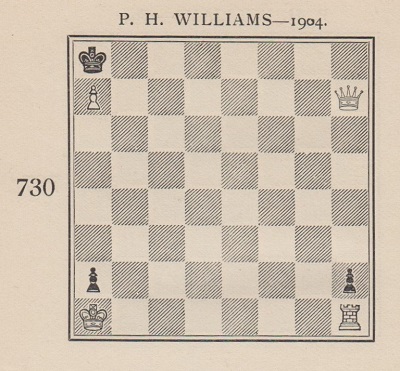

This problem was set by P.H. Williams. The source will be given in a future C.N. item, together with the solution (which, perhaps understandably, was rather hidden away by Williams).

(9930)

The problem in C.N. 9930 was given by P.H. Williams under the heading ‘Ingenious Puzzle’ on page 280 of the Chess Amateur, June 1909. In the ‘Answers to Correspondents’ section on page 345 of his August 1909 column he wrote:

‘A. Mendes da Costa: White’s Rs at Q5 and KB5, Kt at KKt5; Black K at K4 – an impossible position, of course, but mate.’

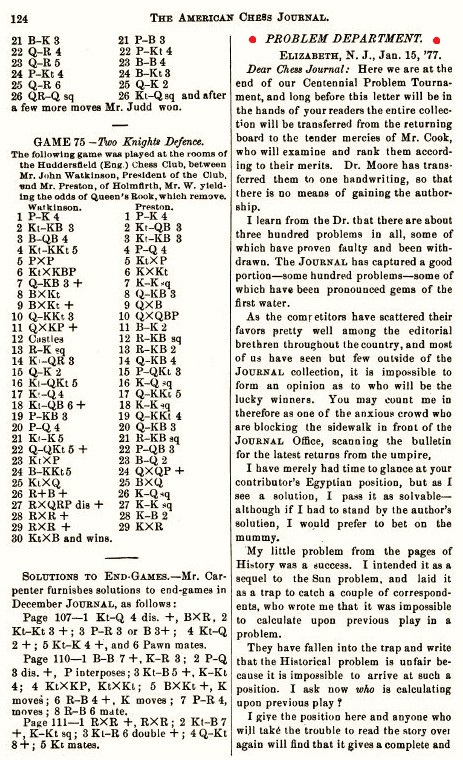

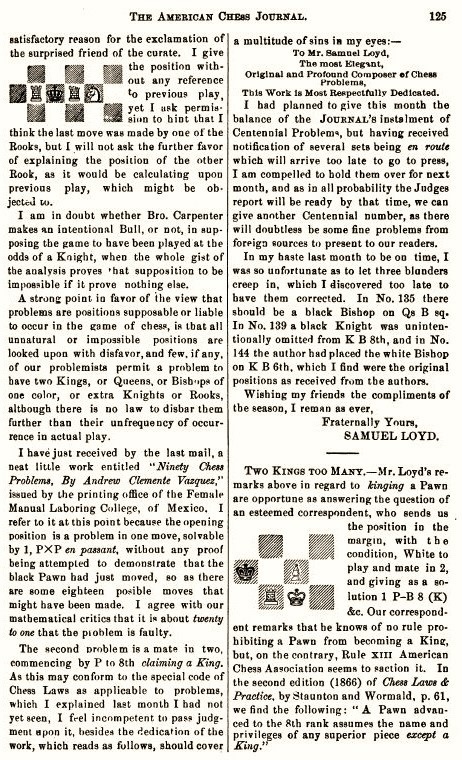

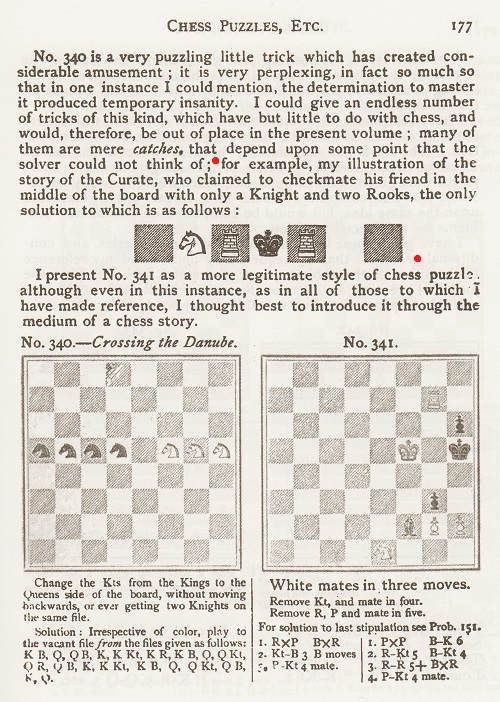

As noted by Michael McDowell, the composition is on page 52 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913):

Our correspondent also points out White’s comment about Loyd on page 53:

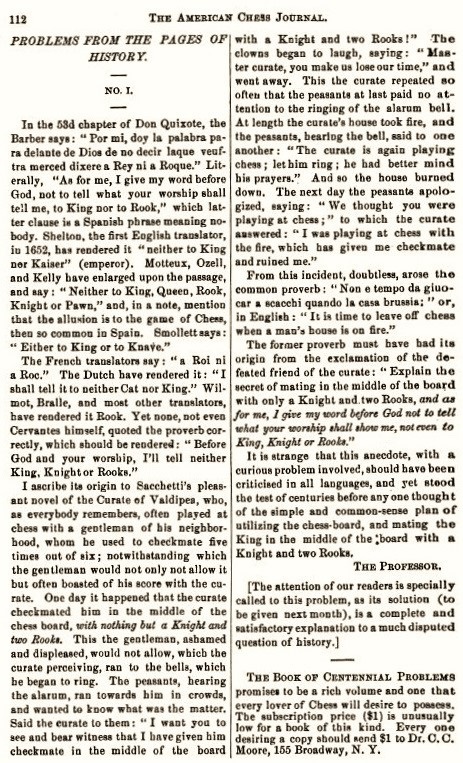

‘His wood-cuts in the American Chess Journal testify to his skill in this most difficult branch of work. There was often a whimsical characteristic concealed in his engravings. I remember the one of Harrwitz, excellently done; but if one looks closely at the board before him, at which Harrwitz is looking with serious consideration, one finds that Loyd has depicted on it that absurd position shown in No. 55.’

The illustration (based on the photograph in C.N. 6286) was published at the end of the December 1878 edition of the American Chess Journal:

Below is the picture’s earlier appearance, on page 1566 of the Scientific American Supplement, 17 November 1877:

Regarding the book extract above, the date in the reference ‘American Chess Journal, December 1876’ is not, as might be imagined, an error for December 1878. Both issues of the periodical had material on the position.

Page 112 of the December 1876 edition:

The solution was published on pages 124-125 of the January 1877 issue:

Finally, the reference ‘Str., p. 177’ in A.C. White’s book is to Loyd’s volume Chess Strategy (Elizabeth, 1878). The full page:

(9935)

From C.N. 10102:

No information has yet come to light on the excelsior composition in C.N. 9975, taken from page 12 of Ideal-Mate Chess Problems by Eugene Albert (Davis, 1966):

Early recognition of Teed came from Sam Loyd on page 1788 of the Scientific American Supplement, 23 February 1878:

The ‘little gem’ regarding which Loyd remarked, ‘we have never found a two-move problem that gave us more trouble to solve’:

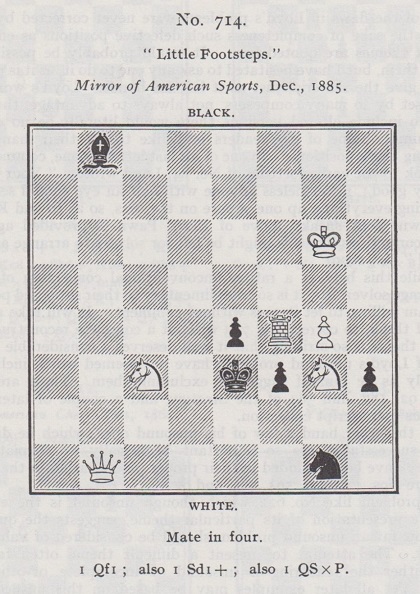

Page 53 of My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins (New York, 1974) reported that one of Fischer’s favourite volumes was Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913). Below is a feature on pages 456-457:

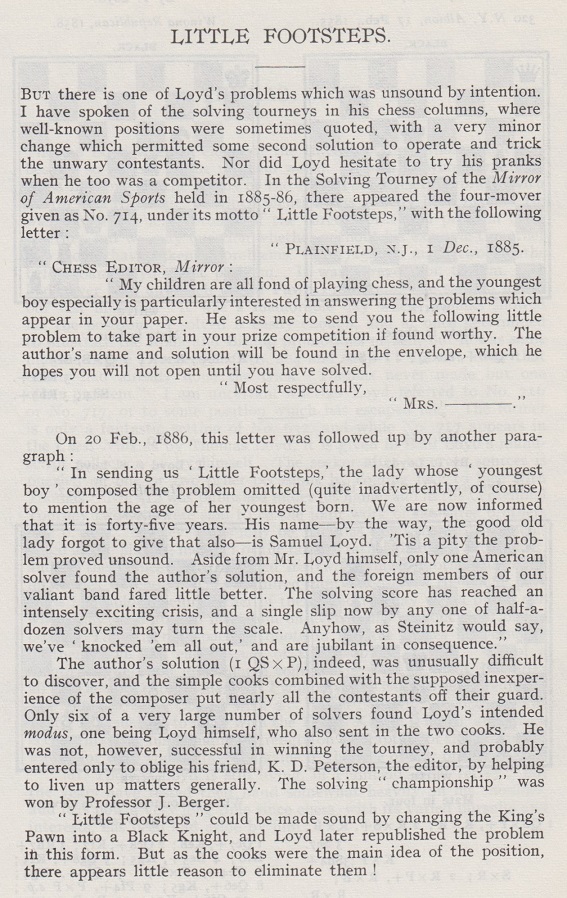

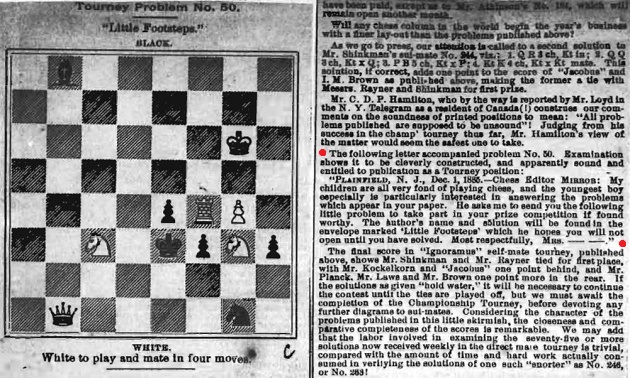

A run of the Mirror of American Sports chess column can be viewed online, in two parts, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, and the cuttings concerning Loyd’s ‘Little Footsteps’ problem are shown below with the Library’s permission.

2 January 1886

20 February 1886

(10239)

An extract from C.N. 11375:

Page 31 of the March 1982 Chess Life:

Discussing Sam Loyd, Benko offered this addition:

For further information (including C.N. 11382) see Pal Benko (1928-2019).

From page 244 of 777 “Chess Miniatures in Three” by E. Wallis (Scarborough, 1908):

The composition is in our feature article on P.H. Williams, but when exactly did it first appear in print? Problem databases give the source as ‘Christmas Greeting, 1904’, which suggests that it was a personal communication from Williams to colleagues, at least some of whom may be expected to have published it.

An unsuccessful search in the Morning Post has provided, at least, some quotable general remarks by Williams, on page 8 of the 19 December 1904 edition:

‘Regarding the relative merits of slender and ponderous three-movers much may be said. Your readers may notice that my three-movers are always of slight build, and, while I do not claim much difficulty, I do, I believe, secure a fair amount of neatness. When solving the work of others, I put elegance a long way ahead of difficulty. The miniature seems to me the essence of problematic beauty, and though there are, of course, many splendid compositions of heavy build, they do not, as a class, appeal to me. (I speak of three-movers only.) Take, for instance, Loyd’s famous Checkmate prize-winner; the main play is undoubtedly brilliant, but, if the outlying pieces are touched, mating positions will result which are positively hideous, to say nothing of duals. The more ugly the by-play the more is the beauty of the main-play discounted. Not so with a good miniature; play any move of Black, and a beautiful mating position is or should be produced. Duals in a miniature are, to my mind, inexcusable, and I would rather abandon a position than cure a defect by additions, since every added piece seems to weaken the charm of the initial position.’

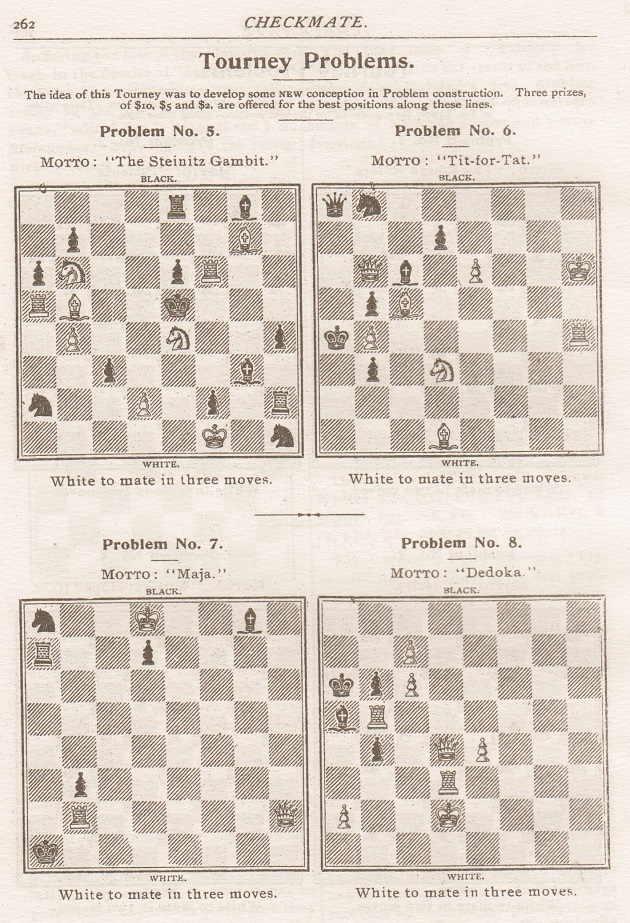

‘Loyd’s famous Checkmate prize-winner’ (motto: ‘The Steinitz Gambit’) was first published on page 262 of the August 1903 issue of Checkmate:

The Canadian magazine announced that Loyd had won first prize ($10) on page 66 of the January 1904 edition.

(11686)

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) adds a reference to Loyd on the subject of chess grandmasters:

‘We present this week a choice chess-nut from the hands of the problem grand master, Mr Samuel Loyd.’

Source: Philadelphia Times, 7 March 1880, page 2.

(12102)

See also Steinitz Stuck and Capa Caught.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.