Edward Winter

The present discussion of sacrifices complements various feature articles mentioned in the Factfinder, including the following:

Queen Sacrifices

The Double Bishop Sacrifice

Chess Gambits

The Fox Enigma

Anastasia’s Mate

Boden’s Mate

The Smothered Mate

What is a Chess Combination?

An attractive variation on the double rook sacrifice theme:

‘Dr van B.’ – Wilhelm Gudehus

Amsterdam, 1919

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Bg5 Qa5+ 6 Qd2 Bb4 7 c3 Nxe4 8 cxb4 Qxg5 9 Qc2 Nd6 10 Nb5

10…Nxb5 11 Qxc8+ Ke7 12 Qxh8 Nc6 13 Qxa8 Qc1+ 14 Ke2 Nbd4+ 15 Kd3 Qc2+ 16 Ke3 Nf5+ 17 Kf3 Ne5+ 18 Kf4 Qxf2+ 19 Kxe5 Qd4 mate.

Source: pages 40-41 of Wilhelm Gudehus Ein Meister des Schachspiels by H. Römmig, a book published in 1920.

Databases give a 1980 game which went similarly (though with transpositions) but in which Black missed 18…Qxf2+.

(2252)

The year after the Gudehus game, even a prominent master fell victim to the temptation of winning the two rooks:

E. Werner – Rudolf Spielmann

Occasion?

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 Nf3 d6 5 d3 Bg4 6 Be3 Nd4 7 Bxd4 Bxd4 8 h3 Bh5 9 g4 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 Bg6 11 Qb1 Qc8 12 h4 Qxg4 13 Qxb7 Qxf3 14 Bb5+ Ke7 15 Qxc7+ Kf8 16 Qc6 Qxh1+ (Nimzowitsch pointed out that Black should have played 16…Rd8, and if 17 Qc7 then 17…Qxh1+, followed by 18…Qxh4.) 17 Kd2 Qxa1 18 Qxa8+ Ke7 19 Qe8+ Kf6 20 Qd8+ Resigns.

Source: Tidskrift för Schack, July-August 1920, page 143.

When the latter game (C.N. 2542) was added on page 73 of A Chess Omnibus, we pointed out that it was played in an eight-game simultaneous exhibition.

On page 37 of the 5/1999 New in Chess Gregory Serper referred to a game in which he sacrificed all his pieces:

Gregory Serper – Ioannis Nikolaidis

St Petersburg, 1993

King’s Indian Defence

1 c4 g6 2 e4 Bg7 3 d4 d6 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 Nge2 Nbd7 6 Ng3 c6 7 Be2 a6 8 Be3 h5 9 f3 b5 10 c5 dxc5 11 dxc5 Qc7 12 O-O h4 13 Nh1 Nh5 14 Qd2 e5 15 Nf2 Nf8 16 a4 b4 17 Nd5 cxd5 18 exd5 f5 19 d6 Qc6 20 Bb5 axb5 21 axb5 Qxb5 22 Rxa8 Qc6 23 Rfa1 f4 24 R1a7 Nd7 25 Rxc8+ Qxc8 26 Qd5 fxe3 27 Qe6+ Kf8 28 Rxd7 exf2+ 29 Kf1 Qe8 30 Rf7+ Qxf7 31 Qc8+ Qe8 32 d7 Kf7 33 dxe8(Q)+ Rxe8 34 Qb7+ Re7 35 c6 e4 36 c7 e3 37 Qd5+ Kf6 38 Qd6+ Kf7 39 Qd5+ Kf6 40 Qd6+ Kf7 41 Qxe7+ Kxe7 42 c8(Q) Bh6 43 Qc5 Ke8 44 Qb5+ Kd8 45 Qb6+ Kd7 46 Qxg6 e2+ 47 Kxf2 Be3+ 48 Ke1 Resigns.

Remarkable indeed.

(2313)

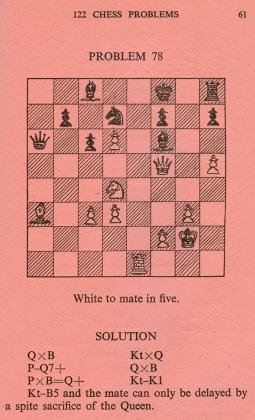

C.N. 2180 (see page 242 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) raised the question of the largest number of sacrifices on consecutive moves. A case with four was quoted (Lund v Nimzowitsch, Kristiania, 1921), but now we note five in this position on page 9 of Combination in Chess by G. Négyesy and J. Hegyi (Budapest, 1965):

The caption states only ‘Cohn – Cisar 1944’, and the finish is given as follows: 1 Nb6 Qxh1+ 2 Kd2 Qxa1 3 Nxf7+ Bxf7 4 Bc7+ Kxc7 5 Qe5+ Kxb6 6 Qc5+ Ka5 7 b4 mate.

Can any reader supply further details about the game and occasion?

(2973)

Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) writes:

‘This game was submitted to the “Readers’ Games” department of the April 1944 Chess Review (page 24). Al Horowitz’s introduction is:

“The game begins with a picayune omission and culminates with a double rook sacrifice, a double knight sacrifice and a bishop thrown in for good measure. The game was submitted by W.F. Streeter, eminent Ohio chess missionary, who writes: ‘I am getting very tired of the dull junk I am compelled to watch most of the time.’”’

J. Cohn – C. Chiszar

Occasion?

Caro-Kann Defence

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Qb6 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 Bc4 Qb4+ 7 Ned2 e6 8 c3 Qb6 9 h3 Bh5 10 g4 Bg6 11 Qe2 c5 12 h4 h5 13 Ne5 Ne7 14 Bb5+ Kd8 15 a4 cxd4 16 Ndc4 Qc5 17 Bf4 a6 18 cxd4 Qd5 (Reaching the diagrammed position from C.N. 2973.) 19 Nb6 Qxh1+ 20 Kd2 Qxa1 21 Nxf7+ Bxf7 22 Bc7+ Kxc7 23 Qe5+ Kxb6 24 Qc5+ Ka5 25 Bd3+ Kxa4 26 Bc2 mate.

Our correspondent points out that at the end of the combination White’s play has been improved by the Hungarian book.

(2979)

From Chess: the Need for Sources:

As shown in Dimitrije Bjelica – A Unique Chess Writer, page 171 of Dimitrije Bjelica’s Wonderful world of chess quotes Mikhail Tal:

‘There are two kind of sacrifices – the corrects ones, and mine’s.’

Before being tossed into the Bjelica mangling machine, the Tal quote was something like:

‘There are two kinds of sacrifices – sound ones, and mine.’

We write ‘something like’ because other wordings can be found, such as ‘two types of sacrifice’, but the above version is what Anthony Saidy gave on page 303 of the June 1973 Chess Life & Review. However, he merely reported there that Tal ‘once said’ it.

Chess literature teems with things that players purportedly ‘once said’, ‘said on one occasion’, ‘used to say’, ‘liked to say’ and other vague variants, but what is the truth about the remark ascribed to Tal? When did he say, or write, such a thing, and in which language? When was it first recorded in print? What was the context? Did it relate to a specific game? What indication, if any, did Tal give that such a statement was made in jest (or, as anecdotalists like to say, ‘with a twinkle in his eye’)?

From page 22 of Relax with Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948):

‘It was that exuberant phrase-maker and paradox-monger Dr Tartakower who once remarked that a pawn sacrifice requires more skill than does a queen sacrifice. The reason? Sacrificing the queen calls for exact calculation of a quick finish. The pawn sacrifice, on the other hand, involves an intuitive flair possessed as a rule only by the great masters.’

Where did Tartakower make such a remark?

(6104)

From page v of Chess Brilliants by I.O. Howard Taylor (London, 1869):

‘Position is everything. To give up a pawn is sometimes a bolder venture than to abandon a queen.’

(6116)

Wanted: early references to pawn offers being the best or hardest type of chess sacrifice.

An example (‘Pawn sacrifices are the finest sacrifices after all’) comes from A. Becker’s notes to Réti v Tartakower, Hastings, 31 December 1926, on pages 2-4 of the January 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung. 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 d4 d5 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bg5 h6 6 Bxf6 Bxf6 7 e3 O-O 8 Qb3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 c5 10 dxc5 Nd7 11 Ne4 Nxc5 12 Nxf6+ Qxf6 13 Qc2 b6 14 O-O Bb7 15 Nd4 Rac8 16 Qe2 e5:

Tartakower annotated the full score in the first volume of his Best Games collection and commented that 17...b5 was ‘one more illustration of the paradox of a chess author that “the principal finesses in chess conflicts are furnished by pawn moves”.’ He concluded, ‘This is one of my best games’.

From page 56 of the February 1927 BCM:

‘The tit-bit of the round was expected to be the Réti-Tartakower game; but the former, who was evidently tired out by his six hours’ match-chess plus four hours’ blindfold display the previous day, did not do himself justice. Tartakower secured an endgame advantage on the queen-side, and playing with relentless accuracy he won the game in 45 moves.’

(9859)

A comment on page 45 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by Fred Reinfeld and Irving Chernev (New York, 1933):

‘From the aesthetic point of view, there are few effects in chess so pleasing as a subtly planned and skillfully executed pawn sacrifice. The more unobtrusive the move, the less obvious – all this contributes to its artistry.’

(11144)

‘A pawn sacrifice may be more brilliant than a queen sacrifice ...’

Source: Australasian Chess Review, November 1936, page 314, from the introduction to Reshevsky v Vidmar, Nottingham, 1936.

(11771)

A game received from Lawrence Stevens (Temple City, CA, USA):

Timothy Thompson – Lawrence Stevens

Pellant Memorial, Pasadena, 14 August 2009

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 g6 6 Be3 Bg7 7 f3 Nc6 8 Qd2 O-O 9 Bc4 Bd7 10 O-O-O Qa5 11 Kb1 Rfc8 12 Bb3 Ne5 13 g4

13...Rxc3 14 Qxc3 Qxc3 15 bxc3 Rc8 16 g5 Ne8 17 f4 Nc4 18 Bc1 b5 19 Rhe1 Nb6 20 e5 dxe5 21 fxe5 e6 22 Bf4 Nc7 23 Ne2 Ncd5 24 Bxd5 Nxd5 25 Kb2 Bc6 26 Rxd5 Bxd5 27 Nd4 Bf8 28 a3 a6 29 Rd1 Rc4 30 Bg3 Be7 31 h4 Bxa3+ 32 Kxa3 Rxc3+ 33 Kb4 Rxg3 34 Ra1 Bb7 35 Rd1 Rg4 36 Kc5 Bd5 37 Ra1 Rxh4 38 Rxa6 Rg4 39 Rb6 Rxg5 40 Rxb5 Rxe5 41 Kd6 Re4 42 Rxd5 exd5 43 Kxd5 Rxd4+ 44 Kxd4 h5 45 c4 h4 46 c5 Kf8 47 White resigns.

Our correspondent asks whether any games between masters have featured four sacrifices of the exchange.

(6273)

From page 140 of the May 1952 BCM, in an article by E.G.R. Cordingley:

‘A spite check or spite sacrifice? The phrase is not mine, but it sounds self-explanatory. A spite sacrifice is one where you give up a piece merely to stave off worse disaster, though it merely prolongs the length, not the result of the game. ... A spite check merely adds to the length of the game and similarly serves no useful purpose.’

The only book in which we recall seeing the term ‘spite sacrifice’ is Cordingley’s 122 Chess Problems, Puzzles, Studies and End Games (undated, but published in London in 1945 or 1946):

(6967)

See also The Spite Check in Chess.

Our item below appeared on pages 21-22 of the Autumn 1996 Kingpin:

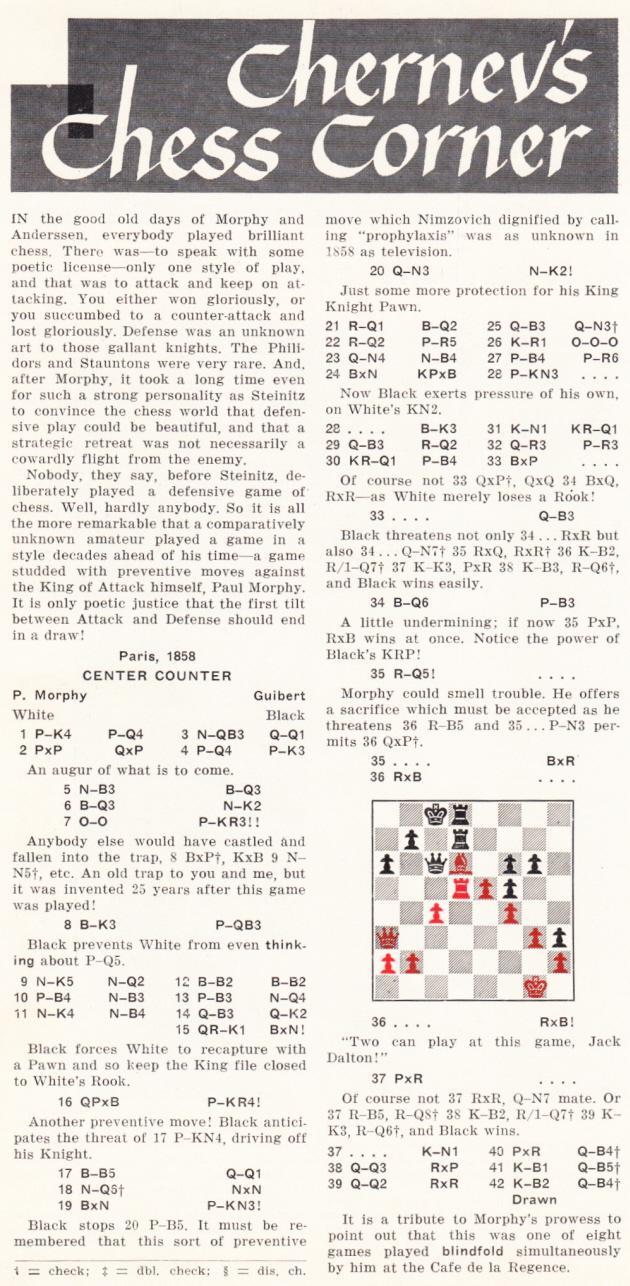

When was the Bxh7+/Ng5+ attack first played? In The Chess Companion Irving Chernev annotated the game Morphy v Guibert, Paris, 1858. After Black’s 7...h6, he wrote (page 186):

‘Anybody else would have castled and fallen into the trap 8 BxPch KxB 9 N-N5ch, etc. An old trap to you and me, but it was invented 25 years after this game was played!’

Chernev contradicted himself two pages later on (an item reprinted from his column in the July 1953 Chess Review):

‘Another little idea that Paulsen anticipated is the ritual sacrifice of BxPch in the French Defense. Credit is usually given to Fritz, who surprised Mason with it in the Nuremberg tournament of 1883. So here to dispute the claim is an entry from a match [Paulsen v Schwarz] played in 1879.’

But what about Greco’s use of Bxh7+/Ng5+ in the early seventeenth century? An example even appears on page 90 of a previous book by Chernev, 1000 Best Short Games of Chess.

Page 331 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves mentioned that in 1925 the second issue of Les Cahiers de L’Echiquier Français (page 59) suggested that the Fritz v Mason game was the earliest specimen of Bxh7+ in a tournament game.

Chernev’s article about the Morphy game had originally appeared on the inside front cover of the April 1950 Chess Review:

Is any biographical information available about Guibert?

(7979)

An oddity in the online Oxford English Dictionary (registration is required to consult it) is that the entries for ‘sacrifice’, as a noun and a verb in the chess sense, have nine citations without any attempt to quote early examples. The oldest both date from 1915 (pages 25 and 224 of Chess Strategy by Ed. Lasker, translated by J. du Mont), whereas from Google Books it is immediately clear that the term had been in use centuries earlier.

Which was the first chess book to contain the word?

(8328)

Browsing in the online dictionary, we came to the noun ‘sac’, with this as the entry’s oldest citation:

‘A careful study of the position after the “sac” shows that White will win the opponent’s queen in return.’

That was on page 249 of the November 1965 Chess Life, the writer being Erich W. Marchand. For the verb, Google Books provides an old example, from page 104 of the June 1901 Checkmate. In the annotations to a Greco Counter-Gambit game between Stout and Mlotkowski in Philadelphia, ‘in the Mercantile Library cup tournament now in progress’, this position arose:

After 14 Nxf6+ Qxf6 the note reads:

‘Sacking pawn for development.’

Acknowledgement for the scan: Cleveland Public Library

In C.N. 415 W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘The verb to sac is with us; the participle sacing still gives one a jolt.’

That was in 1983. As also shown in Chess and the English Language, C.N. 1694 quoted from page 66 of Playing to Win by James Plaskett (London, 1988):

‘For the next half-dozen moves a cardinal consideration is the efficacy of possible “sacs-back” on d5.’

(12054)

From page 54 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945):

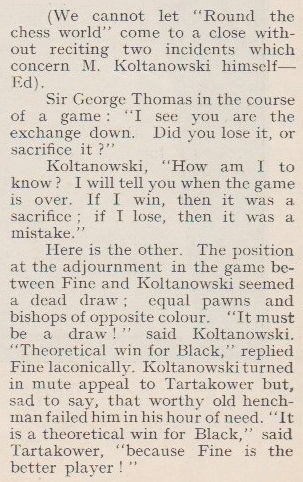

Elsewhere (e.g. on page 73 of CHESS, December 1972) the observation has been quoted as a remark by George Koltanowski to Sir George Thomas.

An editorial note (by B.H. Wood) appeared at the end of an article by Koltanowski on pages 180-181 of the 14 January 1936 issue of CHESS:

On page 87 of With the Chess Masters (San Francisco, 1972) Koltanowski named E.S. Tinsley as his interlocutor and referred to his queen, and not the exchange:

The following page showed the game (Koltanowski v E.G. Sergeant, Hastings, 31 December 1928), which reached this position after Black’s 19th move:

No notes were supplied, but Koltanowski punctuated his next move, Qxc5, with ‘?!’. The game was also published, storyless, on pages 83-84 of his book Chessnicdotes 1 (Coraopolis, 1978) with notes from The Field (and one analytical addition by Koltanowski towards the end of the game).

On page 54 of the second volume of Chessnicdotes (Coraopolis, 1981) it was back to Sir George Thomas and the ‘exchange’ version from CHESS in 1936:

(9451)

C.N. 2844 began as follows:

‘Chess booklet for sale. My once in a lifetime published chess brilliancy by Gerald Castleberry. Get three published games for 49 cents – my game as a free gift along with Anderson’s “Immortal Game” and a Morphy brilliancy. Send SASE and 49 cents to Gerald Castleberry [followed by a postal address in Bell, CA, USA].’

Respondents to this alluring advertisement (Chess Life, October 1983, page 50) received a small-format, eight-page volume by ‘USCF member G. Castleberry’, who also billed himself on the front page as:

‘author of the published statement: “In chess the sacrifice of material for positional advantage is considered brilliant strategy, if it works”.’

In reality, this is little more than a variant of the old Koltanowski quip (see CHESS, 14 January 1936, page 181), ‘If I win, then it was a sacrifice; if I lose, then it was a mistake.’

Tartakower is often attributed the remark that it is better to sacrifice the opponent’s pieces, but on what basis?

On page 1 of the New York Times, 16 February 1927 Capablanca wrote about Vidmar:

‘In London, in 1922 (where from the beginning he was a contender for chief honors), while talking about one of the weaker participants, he made the following typical remark:

“He has not learned yet to sacrifice his opponents’ pieces instead of his own.”

He meant, of course, that while a good many players will always look for a chance to sacrifice something in order to obtain a so-called brilliant victory, the real player knows that a sacrifice is only a means to an end, a weapon only to be used when no safer course is available.’

The full article is on pages 154-156 of our monograph on Capablanca. As shown on page 249, the Cuban made similar points in a lecture in Cuba on 25 May 1932:

‘As regards play in general, you will often meet players, especially inexperienced ones, who readily give up pawns, and sometimes even pieces, for an attack. I do not criticize this, because I believe that players must hold the initiative and attack as much as possible. But they should do this as a means of developing their imagination, not in the belief that this is a better way of playing. In this connection I will relate an anecdote about Dr Vidmar, one of the best players in the world who is also a man of science and a man of great ingenuity. At the London Tournament in 1922, in which we both participated, there was a relatively young player who did not have much experience. On a certain occasion, in a game in which he was carrying out a violent attack he sacrificed a piece (or two or three pawns; I do not remember exactly), but it could be seen that this gentleman, despite the attack, would reach an endgame a piece (or pawns) down. With regard to this case, Vidmar remarked that “he had not yet learned that it was the opponent’s pieces that had to be sacrificed”. I mention this anecdote because in reality one should never sacrifice anything when one is playing to win. Although, I repeat, it is a good exercise for young players with little experience. But those who are already knowledgeable and aspire to the first rank should do what Vidmar said: try to sacrifice the opponent’s pieces, since otherwise the attack almost always makes no progress. I wish to insist on this point because sacrificing a piece for an uncertain attack can give a bad result; a piece is too valuable to give it up on the basis of pure speculation. To sacrifice a piece one should be absolutely sure that one will quickly gain compensation, and it is recommended to do so, as I said before and repeat now, in order to exercise the imagination when one is a beginner. The experience of a defeat can help him to prevent an attack against him from being successful and to prevent an opponent’s sacrifice when his combination would be correct. On the other hand, when the sacrifice is not good, you can see that the best players in the world have played for years and years without making such offers, although they are often faced with an attack; they have ended up by winning because they gave up nothing except when they saw that the sacrifice was completely sound.’

(9602)

Black to move

In this position from the sixth match-game between Botvinnik and Tal (Moscow, 26 March 1960) Purdy wrote regarding 21...Nf4:

‘Perhaps the most daring sacrifice ever made in a world championship match, for the consequences were certainly not fully calculable. It is easy to see that Black gets two pawns for his piece, but White retains his two bishops and there is no crash on White’s king.’

Source: Chess World, March 1960, page 47.

(9836)

A common example of the plumping process discussed in C.N. 9887 concerns quotations. When plumpers say what a given master ‘once said’, ‘often said’ or ‘used to say’, they are simply opting for one version of what earlier plumpers said was said. No caveats are expressed, and random possibilities are presented as fact.

A dictum usually ascribed to Steinitz is that the best way to refute an offer is to accept it. The wording varies, au gré du preneur, and either ‘gambit’ or ‘sacrifice’ may be plumped for.

The investigator hoping that a McFarland book will resolve the question may turn to William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993), but it fell far short of that publisher’s usual standards. Page 282 attributed this remark to Steinitz:

‘“The refutation of a sacrifice fervently consists in its acceptance” (80).’

The word ‘fervently’ is peculiar, but the matter can be pursued because the ‘(80)’ relates to a source note on page 473. Any hope of a precise reference to, perhaps, one of Steinitz’s books or columns, or to the International Chess Magazine, is dashed. Note 80 merely states:

‘80. Levy & Reuben. The Chess Scene. London: Faber & Faber, 1974.’

So the next step, however unpromising, is to turn to The Chess Scene, which has the following on page 70:

‘The refutation of a sacrifice frequently consists in its acceptance. Steinitz.’

As feared, we are no further forward, except that ‘fervently’ can be seen as Landsberger’s mistranscription of ‘frequently’.

Although they did not bother to say so, the exact wording given by Levy and Reuben was in the entry for Epigrams on page 119 of The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1970):

‘The refutation of a sacrifice frequently consists in its acceptance. W Steinitz.’

Again, no source was supplied.

A few years earlier, the ‘gambit’ version had cropped up twice in book two of The Middle Game by Max Euwe and Haije Kramer (London, 1965):

‘Steinitz would certainly have taken it [a pawn], following his own motto “The only way to refute a gambit is to accept it”.’ (Page 276).

‘“The only way to refute a gambit”, said Steinitz, “is to accept it”.’ (Page 329).

Books co-authored by Savielly Tartakower and Julius du Mont had both the ‘sacrifice’ and the ‘gambit’ versions, with Steinitz mentioned in connection with the former:

‘Steinitz’s dictum that “a sacrifice is best refuted by its acceptance” is here put to the test.’

Source: page 233 of 500 Master Games of Chess, book one (London, 1952).

‘On the principle that the best refutation of a gambit is to accept it.’

Source: page 16 of 100 Master Games of Modern Chess (London, 1954).

From the previous decade, page 178 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948) had this:

‘Steinitz used to say that the way to refute a gambit is to accept it.’

Fine’s text had originally appeared on page 24 of the Chess Review, June-July 1946. On page 43 of the November 1946 issue I.A. Horowitz wrote after 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4:

‘As a rule, and this is no exception, the best way to meet a gambit is to accept it ...’

Larry Evans’ books and articles often referred to the remark sourcelessly, and page 86 of The Italian Gambit by Jude Acers and George S. Laven (Victoria, 2003) even attributed it to him, also sourcelessly:

‘The best way to refute a gambit is to accept it. – GM L. Evans.’

From pages 221-222 of The Human Side of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952), in his notes to an 1860 game won by Anderssen with the Evans Gambit:

‘To decline a gambit in those days was almost as unthinkable as for a gentleman to decline to fight a duel. Offering the gambit was a challenge that one could refuse only at the risk of stamping himself as a sissy and a coward.

Later on Steinitz, with the attitude of “a pawn’s a pawn for a’ that”, gave the quietus to aristocratic chess.’

That brings to mind a paragraph on page 4 of Winning with Chess Psychology by Pal Benko and Burt Hochberg (New York, 1991):

‘Steinitz believed that the choice of a plan or move must be based not on a single-minded desire for checkmate but on the objective characteristics of the position. One was not being a sissy to decline a sacrifice, he declared, if concrete analysis showed that accepting it would be dangerous. There was no shame in taking the trouble to win a pawn. A superior endgame was no less legitimate a goal of an opening or middlegame plan than was the possibility of a mating attack.’

The penultimate sentence will take us on to a related remark regularly ascribed to Steinitz. One example comes from page 228 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played by Irving Chernev (New York, 1965):

‘... as Steinitz once mentioned, “A pawn ahead is worth a little trouble”.’

The observation ‘When in doubt, take a pawn. A pawn is worth a little trouble’ is on page 282 of Landsberger’s above-mentioned book on Steinitz. Again, the reference is ‘(80)’, and again the quote is on page 70 of Levy and Reuben’s The Chess Scene, again without a source.

And so it goes on. Many chess writers do not take even a little trouble and, above all, they pretend to possess knowledge which they do not have. Entire websites are ‘devoted’ to sourceless quotations, that most facile way of filling space, and they are a plumper’s charter.

Assistance from readers in tracking down the exact origins of the gambit and sacrifice remarks will be greatly appreciated.

(9929)

‘And the best way to refute a gambit is to accept it.’

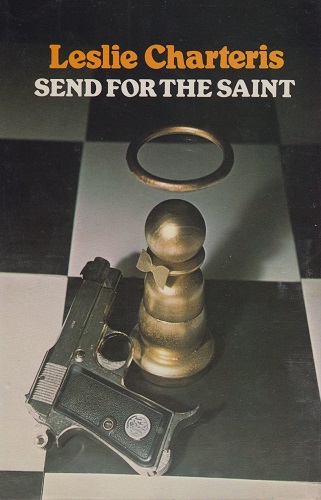

That observation occurs in The Pawn Gambit on page 158 of Send for the Saint by Leslie Charteris (London, 1977):

In a description of an Evans Gambit game the previous page had references to ‘the Göttingen manuscript of 1490’, ‘Bird, Blackman, Staunton, Anderssen’ and ‘Morphy, Steinity’.

The Pawn Gambit (the title The Pawn Gamble can also be found) was not written by Charteris. The contents page of Send for the Saint specified ‘Original Teleplay by Donald James’ and ‘Adapted by Peter Bloxsom’. The corresponding television episode, starring Roger Moore as Simon Templar, was ‘The Organisation Man’ (1968).

(9952)

An observation by Wolfgang Heidenfeld on page 16 of Lacking the Master Touch (Cape Town, 1970):

‘Young players usually see the be-all and end-all of chess in sacrifices (the same, incidentally, applies to some that are not so young. I well remember how, the first time I ever took part in a simultaneous display – against Bogoljubow – a white-haired old geezer went round the room, asking solicitously at every board: “Has the master sacrificed yet?”)’

(10052)

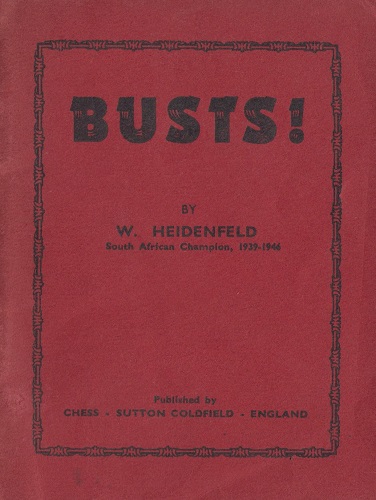

Busts! by Wolfgang Heidenfeld (Sutton Coldfield, 1947) measures only 12cm x 9cm and has 17 pages of text, but anything by Heidenfeld is worth reading. Some general comments from pages 3-4:

‘Chess is difficult enough at its simplest, and anybody, be he the greatest master, may fail to notice a hidden resource to a subtle and involved combination often extending over many moves. I entirely agree with players of the Tartakower or Kurt Richter school of thought, who maintain that a sacrifice – in Spielmann’s terminology a “real” as opposed to a “temporary” sacrifice – cannot simply be classed as incorrect if it induces the opponent to go wrong 90 times out of a hundred – even if subsequent analysis should be able to establish its objective unsoundness. For the practice of tournament play – and it is with such games, not with correspondence chess combinations, that I am concerned – the refutable combination need not be inferior to the abstractly correct combination. One may even go a step further. There may be cases where the 90% combination is preferable to the 100% one – when the latter combination would tax your own resources to such an extent that only a miracle could save you from losing your way under the time-limit. What is the good of the most brilliant and correct conception which yields, say, a sound pawn, when afterwards you are too exhausted to give sufficient attention to the resulting endgame and may lose, not only your hard-earned pawn, but perhaps the game? Chess is a fight, not a science, and men are men and not machines.’

(10084)

How do such things happen?

Instruction manuals sometimes note the difficulty of visualizing a) sacrifices on empty squares and b) backward moves by pieces. Who first made such observations in print? Also requested: practical examples (the less well known, the better).

(11985)

C.N. 182 noted that C.H.O’D. Alexander pointed out in The Penguin Book of Chess Positions, page 17, that attacks on unoccupied squares can be difficult to see – even for experienced players. We gave the game Blackburne v N.N., Canterbury, 1903, annotated by Blackburne:

16 Nf7 (‘16 Nxc6+ would equally have won, but I could not resist this; it is the sort of move sure to intimidate the ordinary amateur. Anyway it somewhat non-plussed my opponent, for he immediately exclaimed, “What have you taken?”’)

For the full game, see Joseph Henry Blackburne.

On page 59 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life by A. Karpov and A. Roshal (Oxford, 1980), the then world champion observed:

‘Sacrifice a piece? Why not sacrifice if, of course, it is correct. Only I do not intend to burn my boats, as some do – burning boats is not my speciality.’

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.