Edward Winter

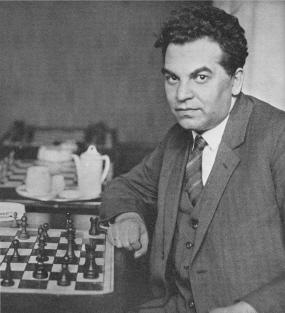

Aron Nimzowitsch (see C.N. 9844 below)

The present article complements, and does not repeat, material given in the following feature articles of ours:

Nimzowitsch’s My System

A Nimzowitsch Story

Nimzowitsch the ‘Crown Prince’

Nimzowitsch v Alapin

The Nimzowitsch Defence (1 e4 Nc6)

Zugzwang

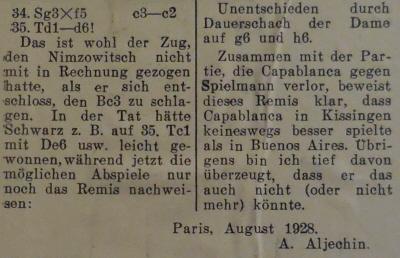

***

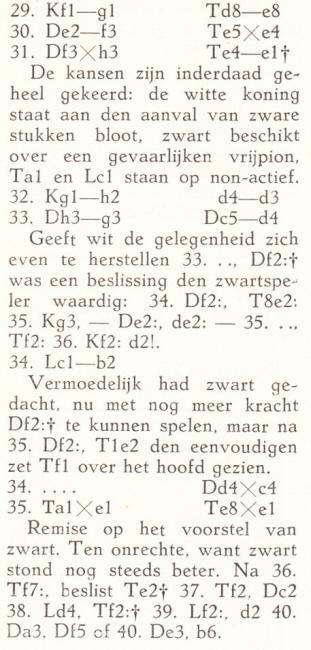

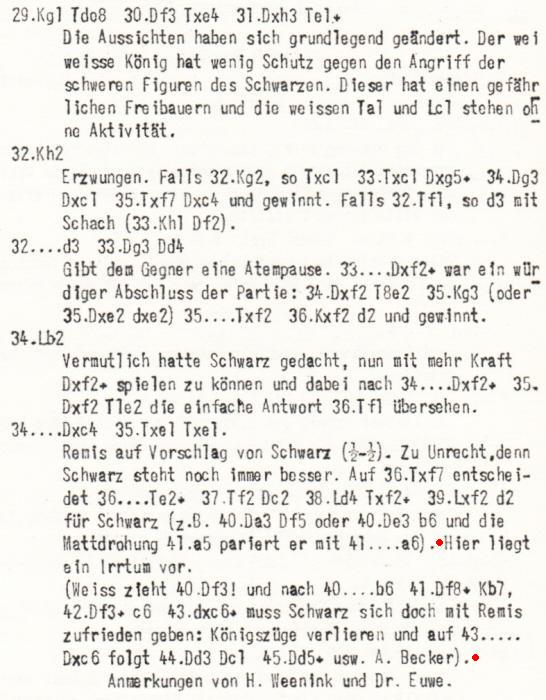

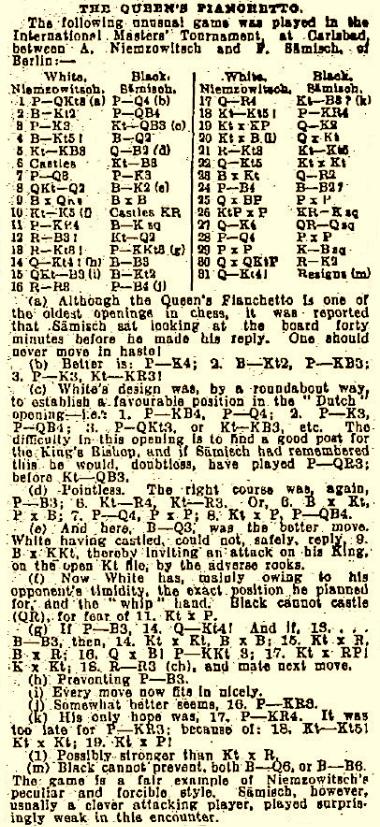

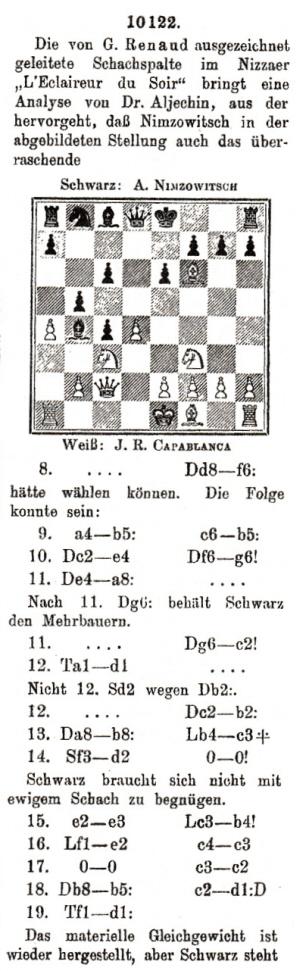

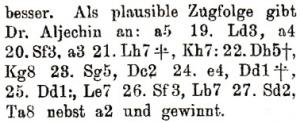

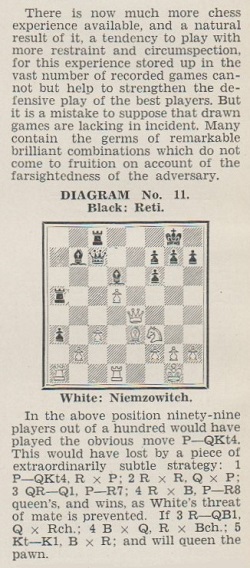

From Nimzowitsch’s book on Carlsbad, 1929 (Dover Publications, New York, 1981) we extract the following:

‘The chess world is obligated to organize a match between the champion of the world and the winner of this Carlsbad tournament – indeed, this is a moral obligation. If the world of chess should remain deaf to its obligation, on the other hand, it would amount to an absolutely unforgivable omission, carrying with it a heavy burden of guilt.’ (page 9)

‘No matter how much we have tried to convince Spielmann of the impossibility of surviving on nothing more than developing and attacking moves (and I have tried hardest of all, through my books and our conversations), still he tries, almost as a matter of principle, to avoid the necessity of defense!’ (page 32)

‘On the whole, I have a hard time remembering someone else’s published analysis, a failing I have no cause to regret. Such analysis is in most cases simply ballast, weighing down the free flight of fantasy!’ (pages 35-36)

‘Capablanca’s games generally take the following course: he begins with a series of extremely fine prophylactic maneuvers, which neutralize his opponent’s attempts to complicate the game; he then proceeds, slowly but surely, to set up an attacking position. This attacking position, after a series of simplifications, is transformed into a favorable endgame, which he conducts with matchless technique.’ (page 43)

‘The Stonewall is not playable if Black cannot bring a knight to e4.’ (page 49)

‘... Spielmann is, in fact, the hardest-working of all the masters, continually searching out the flaws in his game and striving to eliminate them.’ (page 63)

‘... The best variation to use in a tournament is not a merely good line, but more exactly a line which, though good, is considered to be bad.’ (page 64)

‘It is difficult to find anything whatever to say about Becker. He has no recognizable chess physiognomy – indeed, God only knows how he gets through his games ... He is hardly likely to achieve such heights a second time.’ (page 108)

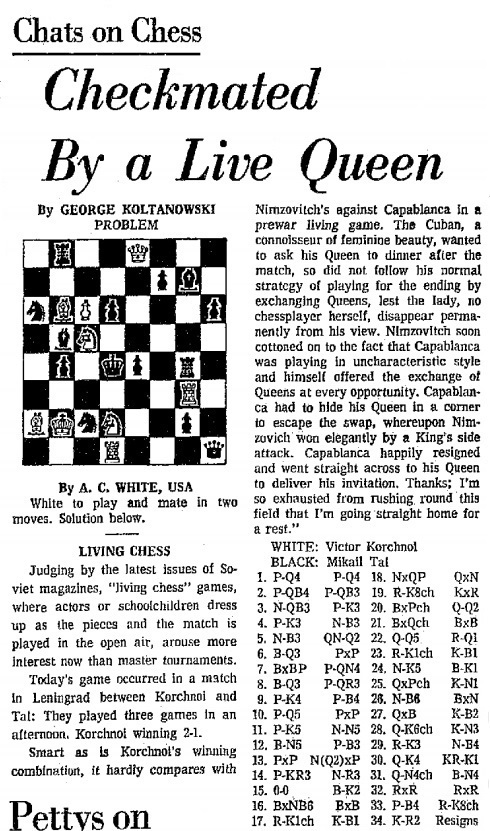

(511)

The March 1989 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez (pages 12-15) has an interview with the Spanish-born master Francisco José Pérez, a Cuban resident since the early 1960s. His reminiscences on Alekhine are of interest, and we give below a brief compendium of some of his replies to F.J. Ochoa de Echagüen:

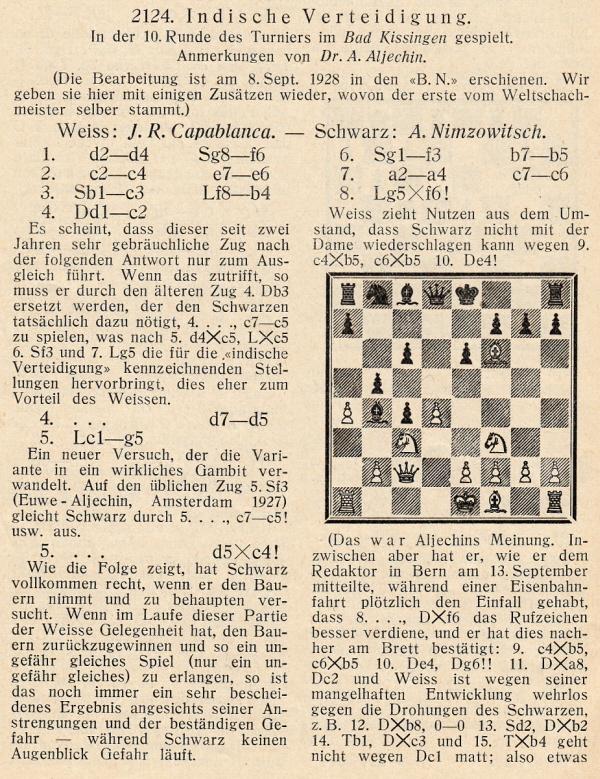

‘He was, possibly, the greatest player of all time. I played four tournament games against him (3½-½ to Alekhine) and many friendly ones. ... He was not very good at fast chess. ... I spent a long time with him. He revised the manuscript of the book Ajedrez Hipermoderno which I wrote with Ricardo Aguilera. The book was a kind of bringing up to date of Réti, along the lines of Masters of the Chess Board. Those were six months of unforgettable collaboration with the master. He was staying at the Hotel Capitol, and two days a week he analyzed with me. Incidentally, I will mention that in general he spoke well of the majority of chessplayers, except Nimzowitsch, who he said was mad.

(1854)

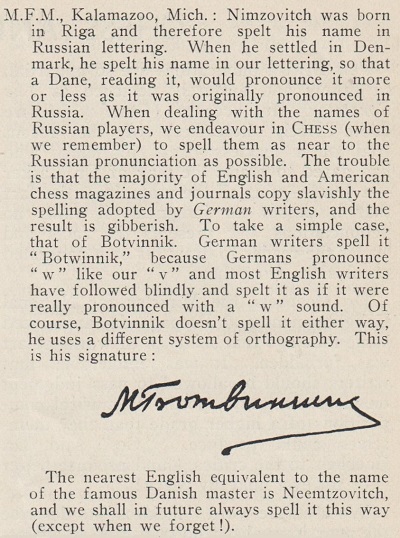

As mentioned on page 271 of Chess Explorations, the spelling of A. Nimzowitsch’s name was discussed in C.N.s 20, 447, 518, 615, 1956 and 1987. The last two of those items are reproduced below from pages 204-205 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

Val Zemitis (Davis, CA, USA) has an original photograph of the Carlsbad, 1911 participants, with many players’ signatures. One of them seems to read ‘Niemzowitsch’ (although the last few letters are unclear), and Mr Zemitis asks why N.’s name is spelt differently nowadays.

At least part of the answer is that later in his career N. himself changed the spelling to ‘Nimzowitsch’. Hanon Russell informs us that his Collection contains several dozen specimens of N.’s signature from 1926 onwards; all are written ‘Nimzowitsch’.

For reference, we add that Nimzowitsch’s ‘old’ signature appeared on page 344 of the October-November 1910 Wiener Schachzeitung. The ‘new’ one was reproduced on page 10 of the January 1927 American Chess Bulletin. In C.N. 447 Jeremy Gaige commented on the various spellings of Nimzowitsch’s name.

(1956)

Below is the full text of Jeremy Gaige’s contribution in C.N. 447:

‘Raymond Keene gives Aron Nimzowitsch, and says that spellings such as Nimzovich and Nimzovitch “are quite simply incorrect” (C.N. 20). I wish I could make flat statements like that, but I am deterred by 20 years of research. In the present case, it could be argued that his correct name is Nimcovičs, to give it the spelling of his native Latvia. Furthermore, anyone checking for books by and about that master in English will not find it in card catalogs under Nimzowitsch, but rather under Nimzovich. In fact, in Chess: An Annotated Bibliography, the reader looking for Nimzowitsch is referred to Nimzovich. Mr Keene would have been on firmer ground if he had confined himself to saying that a) most of the master’s playing career was spent in the German-speaking world, and b) Nimzowitsch is the spelling given on his tombstone, and c) for the reader’s guidance, there are variant spellings. There is usually an ethno-centric bias in such matters, e.g. Wilhelm Steinitz in German sources, William Steinitz in sources in the USA, where he died. It is surely more useful to lay the evidence before the reader and let him judge for himself rather than rapping him on the knuckles.’

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends the following item which appeared in the 1 September 1929 issue of the Czech publication Národní politika:

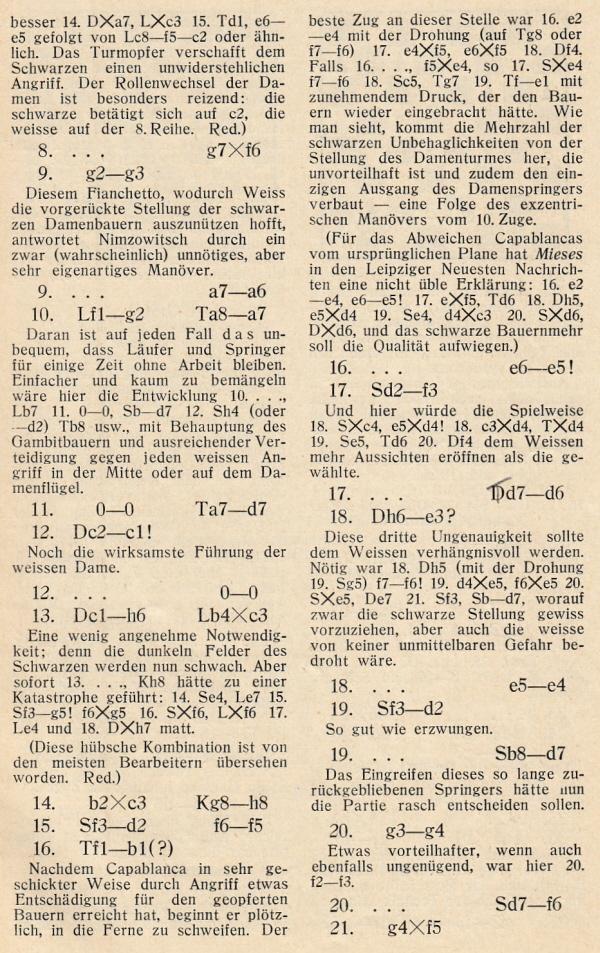

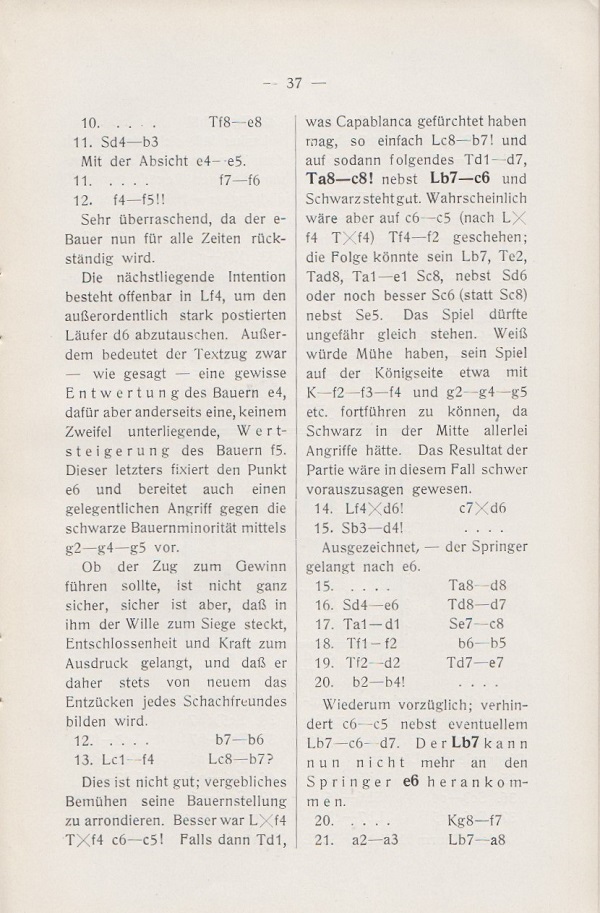

‘Our major problem was how to write his name. Therefore, with his kind permission, we examined his passport, where he had written in his best Latvian “Nimcovičs”. Therefore it is perfectly permissible if, in Czech, we write his name “Nimcovič”. In international tournaments, where German is the international language, he has signed his name “Nimzowitsch”.’

(1987)

For further specimens, see C.N.s 3506, 4685, 5130, 7646, 7831, 7844 and 8793, as well as Chess Autographs.

Regarding London, 1927 the BCM has produced a neat tournament book (exceptionally well illustrated with photographs of the competitors and of their score-sheets – although in the case of the latter it is not always made clear who was the writer) which has excellent annotations from a wide variety of sources. The editor, Raymond Keene, has not managed to avoid repeating the mistake made in Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal of stating that New York, 1927 decided who was to challenge Capa for the world championship. As is well-known, Alekhine’s challenge had already been confirmed beforehand.

We were at a loss to understand a quote attributed to William Winter on page 65 of London, 1927:

‘For my win over Nimzowitsch I am partly indebted to Amos Burn. Before the tournament I happened to mention to him that Nimzowitsch was playing a system, beginning with 1 b3 ... The old master told me that in his younger days he had played many games with the Rev. John Owen who regularly adopted this opening ...’

The trouble with all this is that Burn had died nearly two years before the London tourney took place.

(586)

The Chess Tournament – London 1851 by Staunton has just been reprinted – superbly – by Batsford, as has Nimzowitsch’s Chess Praxis. Mr Raymond Keene’s willingness to supply his company with a Foreword to the latter work is not readily comprehensible when one recalls his words on page 4 of Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal:

‘The English of My System is, by and large, very good and makes a brave effort to capture the spirit of Nimzowitsch’s original German, but, unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the translation of Chess Praxis which I find a poor, maimed torso of Nimzowitsch’s original. If you have no alternative read the translation by all means, but if you possess the merest smattering of German I urge you to read the original. It is well worth the effort.’

(1231)

Yet there are people who find such inconsistencies unblameworthy. After we pointed out Raymond Keene’s Chess Praxis contradiction (C.N. 1231) on page 282 of the September 1986 CHESS, a reply from Mr James Pratt of Basingstoke was printed on page 326 of the November 1986 issue:

‘... Now to Mr Winter. He informs us that Batsford don’t do as good a job as they possibly could. Of course everything can be improved – what is heaven for? Take Chess Praxis by Nimzovich. Keene in A.N. – A Reappraisal – written quite a while ago – points out how poor the translation is in Praxis. Mr Winter points out that he has changed his mind. So what? He’s entitled to. Short and Botterill call Praxis the best chess book they know. If your correspondents wish to attack each other they should either do so over the board or by private letter. “The play’s the thing”.’

Similar crassness from the same Mr Pratt (who is clearly no intellectual power-house) appeared in item b) of C.N. 711. On 21 December 1986 we replied to CHESS, but of course the letter was not published:

The Pratt Guide to Criticism (November CHESS) is fascinating. Since nothing is ever perfect, Winter should not criticize Batsford. Keene, on the other hand, may freely criticize Chess Praxis and contradict himself subsequently. Winter, however, is wrong to criticize such inconsistency. Pratt may write a public letter to criticize Winter for not criticizing Keene in a private letter.

(1424)

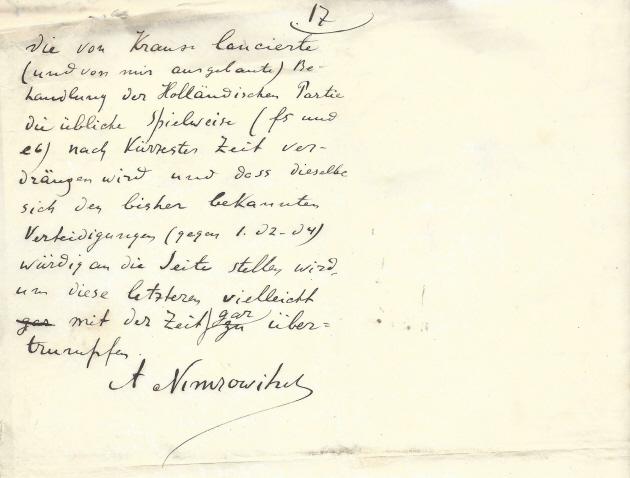

Hanon Russell (Milford, CT, USA) writes:

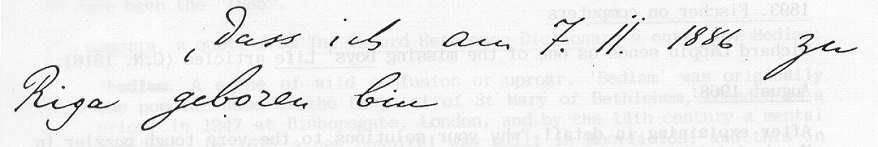

‘While doing some research in my collection, I had occasion to examine Item 966, a letter, in German, from Aron Nimzowitsch to Norbert Lederer dated 9 December 1927. Although my German is not first-class, I did note that at one point Nimzowitsch states “dass ich am 7.ii.1886 zu Riga geboren bin”. I recalled that any source I had seen gave Nimzowitsch’s date of birth as 7 November 1886, not 7 February. A closer examination clearly revealed that the two marks indicating the month of birth were definitely dotted. A second example of the same thing exists in the same letter three lines earlier. I would venture to guess Nimzowitsch’s representation of the month in which he was born may have been mistaken for November, and then the mistake repeated by those who perhaps could not have known any differently. I would welcome response from the readership of Chess Notes. I have shown the original to two elderly Germans living in the United States and both have told me unconditionally that for a letter written in the 1920s, the date shown is 7 February 1886.’

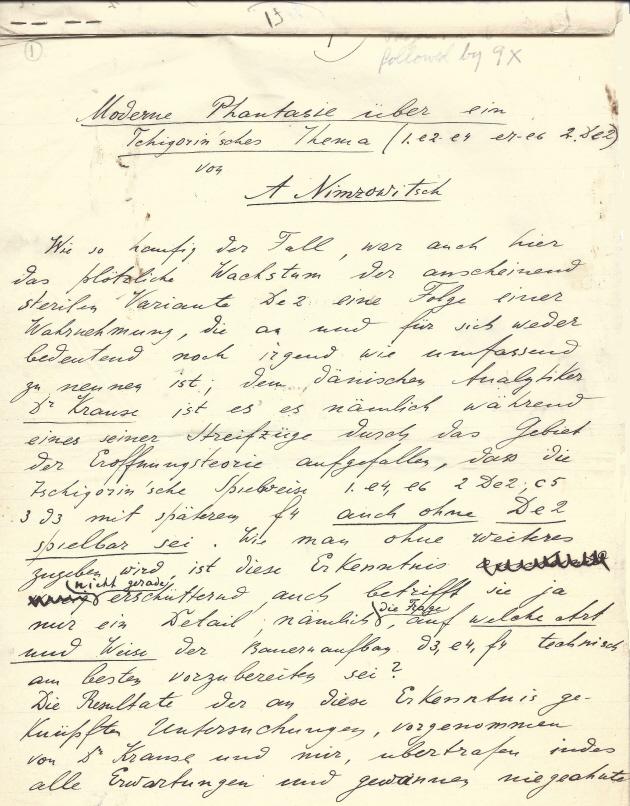

The relevant section of this letter is reproduced below:

A good start would be to find the earliest appearance of ‘7 November 1886’. Clara Millar’s ‘Chess Lovers’ Kalendar’ in The Year-Book of Chess, 1912 gives only 1886. Another standard biographical source is the Teplitz-Schönau, 1922 tournament book, but there (page 598) Nimzowitsch is one of the few masters for whom no birth details are given. Offhand, the earliest instance of ‘7 November 1886’ that we can quote is an article by Capablanca in the New York Times of 16 February 1927 (page 1).

(1894)

Hanon Russell tells us that he recently had a visit from Lothar Schmid, to whom he showed the Nimzowitsch letter discussed in C.N. 1894.

‘He seemed convinced that November, not February, was the correct month of birth for Nimzowitsch, although he confessed he could not offer an adequate explanation for the dots appearing above the “ones”.’

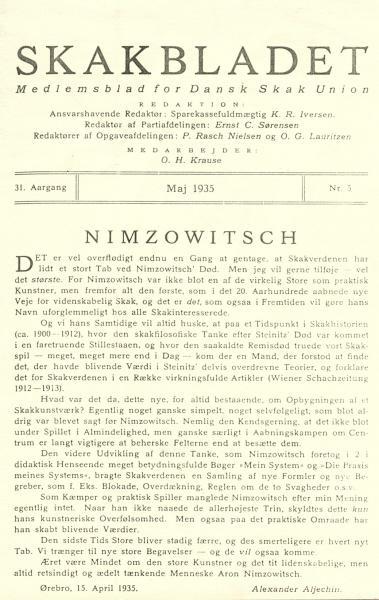

Nimzowitsch died in Copenhagen. We have made a check with the Københavns folksregister: it gives November, not February. We further note that the May 1935 issue of the Danish magazine Skakbladet (page 60) said ‘7 November 1886’; in passing it may also be mentioned that the same magazine contains a 30-line appreciation of Nimzowitsch by Alekhine, written in Örebro on 15 April 1935 [reproduced in C.N. 5275 below].

We regret that on page 507 of the November 1989 BCM, Ken Whyld gives a misleading account of C.N. 1894, which certainly did not say that the month of Nimzowitsch’s birth was definitely February rather than November.

(1931)

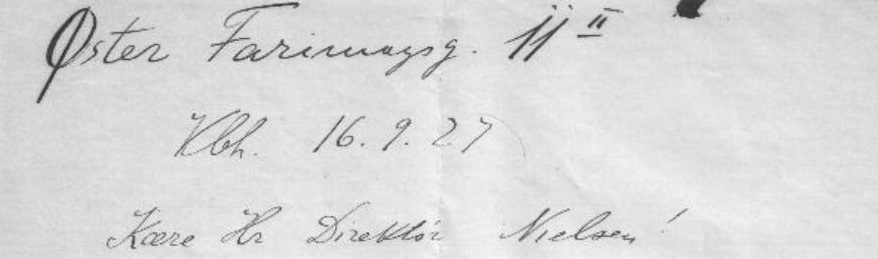

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) sends us a copy of a letter written by Nimzowitsch on 19 September 1927 to G.A.K. Nielsen. Contemporary sources record that at the time Nimzowitsch’s address in Copenhagen was Øster Farimagsgade 11 (second floor), and in the letter to Nielsen he wrote it as follows:

This strongly suggests that in the Lederer letter Nimzowitsch was indeed giving his month of birth as November.

(2879)

Per Skjoldager is writing a book on Nimzowitsch, jointly with Jørn Erik Nielsen, and here he offers an intriguing snippet:

‘C.N.s 1894, 1931 and 2879 discussed the exact date of Nimzowitsch’s birth, and even today there are some who believe that it was 7 February, rather than 7 November, 1886. Our book will present rock-solid proof that 7 November 1886 is the correct date.

Even so, here is a copy of Nimzowitsch’s application form from the University of Zurich. In his own handwriting he gave his date of birth as 9 November 1886. A possible explanation of how Nimzowitsch made that mistake will also be offered in our book.’

Mr Skjoldager would like to hear from readers who possess rare material on Nimzowitsch, and we shall gladly pass on any messages received.

(3506)

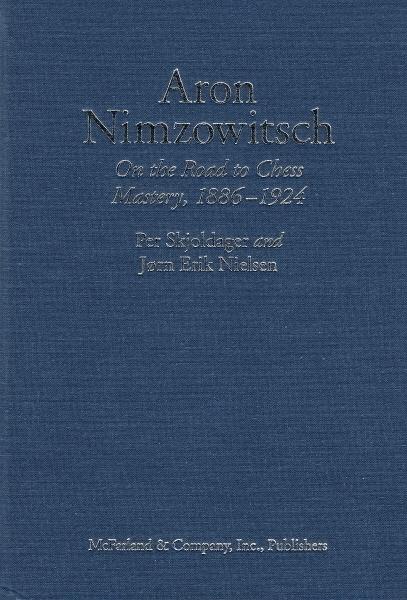

Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012) was briefly mentioned in C.N. 7751. The McFarland chess catalogue has many excellent titles, but even there the Nimzowitsch volume stands out for the excellence of its scholarship.

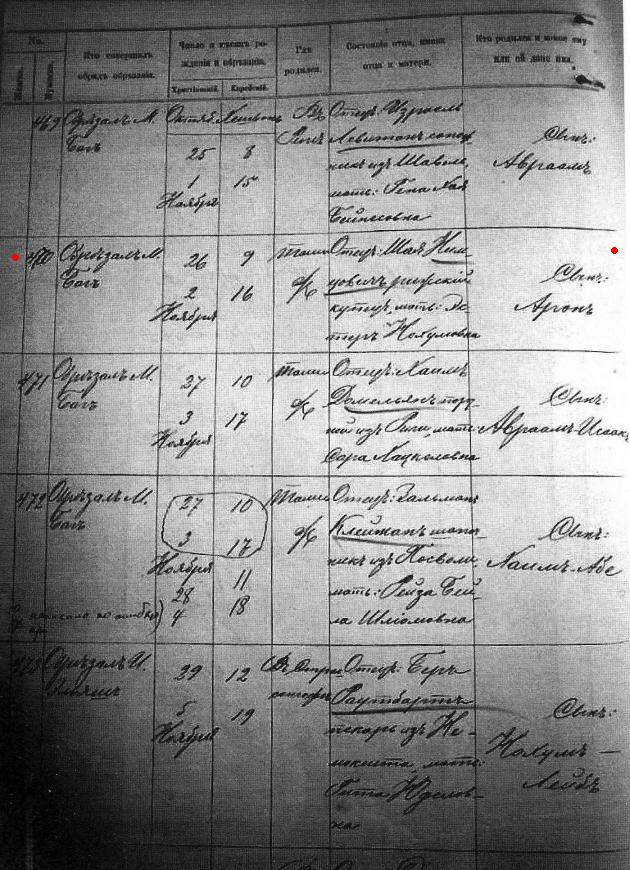

With regard to Nimzowitsch’s exact date of birth, this paragraph is on page 5 of the Skjoldager/Nielsen book:

‘Aron was born on Heshvan 9 according to the Jewish calendar. This corresponds with 26 October 1886 in the Julian calendar, and both dates are equal to 7 November 1886 in the Gregorian calendar. It should be noted that Aron specified his birthday as 9 November on his application form to the university in Zurich. This was not just a slip of the pen since he repeated the mistake when he registered at the Einwohner und Fremden-kontrolle where he specified his birthday as 27 October/9 November 1886. Both dates are wrong, and it indicates that he was so strongly orientated towards Jewish culture and tradition at that time that he was not even aware of the correct corresponding Julian and Gregorian dates.’

A footnote adds:

‘His birth record is kept in the Latvian Historical Archive (fond 5024, inventory 2, file 735).’

The record is not reproduced in the book, and we are grateful to Per Skjoldager for an opportunity to show it here:

(7831)

Addition on 24 October 2024:

Our article Jeremy Gaige reproduces some of his comments about Kenneth Whyld, mentioning the Nimzowitsch matter.

Hanon Russell has a collection of thousands of chess documents representing all periods. Its importance for serious historical research is immeasurable, but here we publish, with his kind permission, some lighter fare: masters’ comments on each other in correspondence.

Letter from Bogoljubow to Capablanca, 7 December 1926 (item 78):

‘Apart from the fact that, for instance, Nimzowitsch is very hostile to me and lately has not missed any opportunity to harm me, I cannot expect fair treatment at the hands of Alekhine, Spielmann or Vidmar. ... As far as Nimzowitsch is concerned, you know as well as I do that he, notwithstanding his fairly good results, is hardly a real grandmaster, so that I am really surprised that people make such a ridiculous fuss over him of late.’

(1999)

See Chess Jottings for other extracts, unrelated to Nimzowitsch.

On page 1 of the New York Times (Sports Section), 16 February 1927 Capablanca wrote of Nimzowitsch:

‘We believe that his strength is his weakness; he plays such bizarre openings and such complicated games that very often he is just as much puzzled as his opponent, if not more so, as to the best course to follow.’

See the chapter on New York, 1927 in our 1989 monograph on Capablanca.

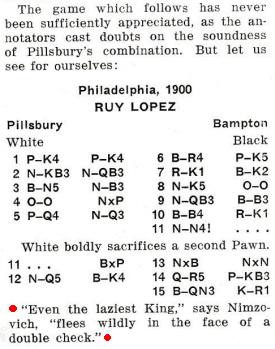

The Ruy López may occur even if White plays 1 d4. The game between J. Berger and A. Nimzowitsch at Carlsbad on 3 September 1907 (a 44-move draw) began 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d6 3 Nbd2 Nc6 4 e4 e5 5 c3 Be7 6 Bb5.

Source: pages 238-239 of the tournament book.

Wanted: other surprising transpositions.

(2100)

See also page 201 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

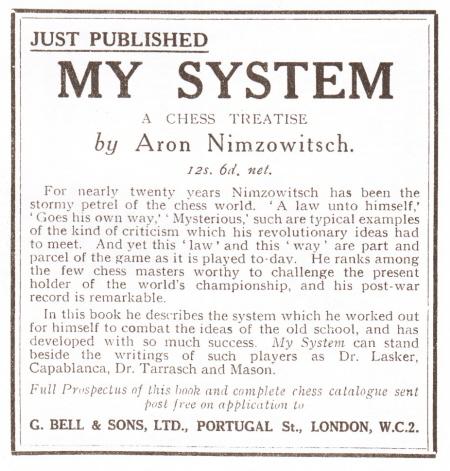

Who in the chess world was ‘The Stormy Petrel’?

The obvious answer may be Nimzowitsch, but he was not the first. Page 574 of the March 1882 Brentano’s Chess Monthly reported that Philip Richardson (1841-1920) attended the Café International in New York only ‘on rainy days, owing to the fact that he was a photographer and, consequently, was released from his duties at the camera in stormy weather; the coincidence of storms and his visits soon attracted notice, and he was promptly dubbed “The Stormy Petrel” by Capt. Mackenzie, and this soubriquet has clung to him to this day’.

(2194)

See too Philip Richardson The Stormy Petrel of Chess by John S. Hilbert (Olomouc, 2009).

The description ‘stormy petrel’ in connection with Nimzowitsch is on page v of My System (London, 1929), at the start of the Translator’s Preface. The translator was Arthur Hereford Wykeham George, using the pseudonym Philip Hereford (BCM, July 1937, page 361).

The relevant text also appeared on the front of the dust-jacket (see C.N. 6237) and in advertising material, such as the following on page 45 of the November 1929 Chess Amateur:

Have any other languages taken up a name such as ‘stormy petrel’ in connection with Nimzowitsch, Richardson or any other player?

(8191)

For further information on Richardson in this context see Chess Jottings.

A forgotten Nimzowitsch exhibition game:

Aron Nimzowitsch – Otto Zimmermann

Berne, February 1931

Caro-Kann Defence

1 e4 c6 2 Nc3 d5 3 Nf3 Bg4 4 d4 e6 5 Bd3 Nf6 6 O-O Be7 7 Be3 dxe4 8 Nxe4 Nbd7 9 h3 Bh5 10 Ng3 Bg6 11 Bxg6 hxg6 12 c4 Qc7 13 Qa4 Bd6 14 Ng5 Bf4 15 Ne2 Bxe3 16 fxe3 Rh5! 17 Nf3 g5 18 c5 Ke7 19 Nh2 Rah8 20 Qd1 Nd5

21 e4!! Ne3 22 Qd2 Nxf1 23 Rxf1 Nf6 24 e5 Nd5 25 Ng3 Nf4 26 Nxh5 Rxh5 27 Qd1 Rh6 28 Qg4 Ke8 29 Nf3 f6 30 h4 Qd7 31 exf6 gxf6 32 Re1 Qh7 33 b4! a6 34 a4 Rh5 35 b5 axb5 36 axb5 cxb5 37 d5 f5 38 Qg3 Qc7 39 Qf2 gxh4 40 Qd4 Nh3+ 41 Kf1 Resigns.

The punctuation above is by Nimzowitsch, who annotated this complex game on pages 49-51 of the April 1931 Schweizerische Schachzeitung.

(2410)

Further evidence that nobody played quite like Nimzowitsch:

Oskar Naegeli – Aron Nimzowitsch

Berne, 10 March 1931

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Ng8 6 Bd2 h5 7 Be2 g6 8 Nf3 c6 9 a3 b6 10 b4 Nh6 11 Bxh6 Rxh6 12 Qd2 Rh8 13 h4 Bf8 14 Ng5 b5 15 Qf4 Qe7 16 a4 bxa4 17 Nxa4 Nd7 18 O-O Bh6 19 Nc5 Nxc5 20 bxc5 Kf8 21 Rfb1 Kg7 22 Rb3 Rf8 23 Rab1 a5 24 Rb6 Qc7 25 Bxh5 Kg8 26 Be2 f6

27 Nxe6 Qxb6 28 Qxh6 Qxb1+ 29 Kh2 Bxe6 30 Qxg6+ Kh8 Drawn.

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, July 1931, pages 123-124.

(2435)

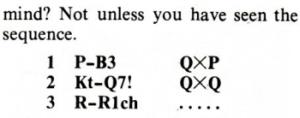

Nimzowitsch’s activities during the First World War are cloaked in mystery, but below is a forgotten game from that period:

Elison – Aron Nimzowitsch

Riga, December 1915

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Be7 6 Be2 O-O 7 O-O Nc6 8 Nxc6 bxc6 9 Bd3 Ng4 10 Bf4 Rb8 11 h3 Ne5 12 Bxe5 dxe5 13 b3 Bb4 14 Ne2 Qh4 15 Ng3 Bc3 16 Rc1 g6 17 Qf3 Qf4 18 Qxf4 exf4 19 Ne2 Be5 20 Rcd1 Be6 21 Rd2 Rfd8 22 Rfd1 Kf8 23 Ba6 Rxd2 24 Rxd2 c5 25 Nc1 c4 26 Ne2 Rb6 27 Bxc4 Bxc4 28 bxc4 Rb1+ 29 Kh2 f3+ 30 Ng3

30…h5 31 h4 g5 32 Kh3 Rh1+ 33 Nxh1 g4 mate.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, June 1918, pages 128-129.

(2509)

As mentioned on page 91 of A Chess Omnibus, the game against Elison appeared with brief notes by Nimzowitsch.

From page 84 of From Morphy to Fischer by Al Horowitz (London, 1973), in a discussion of Capablanca’s performance at New York, 1927:

‘… the situation reached the height of absurdity in his game with Nimzowitsch, where he had to send a message to his opponent (?) through the tournament director to make better moves or he would be unable, with the best will in the world, to avoid winning!’

Horowitz had written similarly on page 206 of Chess Review, July 1949:

‘The prearranged draw is really the blight upon the game. Even some of the greatest masters are guilty of this sin. On good authority comes the story of the Capablanca-Nimzowitsch, New York 1927, fiasco and its hilarious overtones. Capablanca, having first prize clinched, the story goes, agreed to draw with Nimzowitsch. In so doing, Capablanca would avert the effort and Nimzowitsch would insure half a point against the invincible Capablanca. Hence, both were satisfied. The game, however, did not follow conventional lines and Nimzowitsch mangled the defense. Capa was embarrassed! He requested the referee to intervene and advise Nimzowitsch to improve his play. Otherwise, Capablanca would be compelled to win!’

In the following issue (August 1949, page 225) Norbert Lederer commented:

‘In fairness to Capa, it should be noted that he had already secured first prize since he had a three and a half point lead with only three games to play; these were against Alekhine, Nimzowitsch and Vidmar. Capa announced that, in order not to appear favoring one of the three, who were all in the running for second or third prize, he would play for a draw against each of them, and he so informed me as tournament director. Needless to say, I did not relish this attitude, but there was little I could do about it.

During his game with Capablanca, Nimzowitsch indulged in some fancy play and found himself with a practically lost position. Capa then not only asked me to warn his opponent, but actually had to dictate the next four or five moves which Nimzowitsch played with great reluctance as he suspected a double-cross. However, he did follow instructions and a draw was reached four moves later.’

Capablanca referred to the matter in his tournament report in the New York Times, 27 March 1927, pages 1 and 4:

‘Our game with Vidmar needs only a few remarks. The peculiar position in which we found ourselves with regard to the other three leading competitors made us decide to exert ourselves to play for draws unless our opponents threatened to win, since any defeat at our hands would put any one of them out of the running for a prize, without any benefit to ourselves. Our opponent being satisfied to draw, the game could only have one result.

… The same remarks about our game with Vidmar in the previous round apply to our game with Nimzowitsch, except that here we had a chance to win, of which we did not avail ourselves.’

(2527)

Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year) had the following remark (number 196) by Napier on Nimzowitsch’s win over Yates at Carlsbad, 1923:

‘It is witch chess, heathen and beautiful.’

Although seemingly forgotten today, the game below was published in a number of contemporary magazines, including the Chess Amateur, May 1928 (pages 244-245), where Fairhurst bravely annotated it in detail. He expressed a low opinion of White’s opening (6 f4 was censured as ‘A feeble, illogical eccentricity, typical of Nimzowitsch’s play’) but he also commented, ‘The way in which he turns an apparently hopeless position into a brilliant win will certainly evoke the admiration of the reader’.

Aron Nimzowitsch – Berthold Koch

Berlin, February 1928

English Opening

1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 d5 3 cxd5 Nxd5 4 g3 Nxc3 5 bxc3 Bd7 6 f4 c5 7 Bg2 Bc6 8 e4 Qd3 9 Nh3 g6 10 Nf2 Qa6 11 Bb2 Bg7 12 d3 O-O 13 O-O Rd8 14 Qd2 Qa5 15 h4 c4 16 h5 cxd3 17 hxg6 hxg6 18 Ng4 Qc5+ 19 Rf2 Nd7 20 c4 Nf6 21 Nxf6+ exf6 22 Re1 Qxc4

23 f5 gxf5 24 e5 fxe5 25 Rxe5 Rd6 26 Rexf5 Bxb2 27 Qxb2 Rg6 28 Rh5 Rg7 29 Rf6 Be4 30 Rfh6 Bh7 31 Rxh7 Rxh7 32 Rg5+ Kf8 33 Qa3+ Ke8 34 Re5+ Qe6 35 Rxe6+ fxe6 36 Qxd3 Resigns.

(2534)

A striking surprise occurred in this position, from a game against Nimzowitsch in Vienna in March 1905:

Neumann (who, in fact, had the edge) brought about a ‘fortress draw’: 51 Bxe5 dxe5 52 Nxb6 Bxb6.

Source: Schachjachrbuch für 1905. I. Teil by L. Bachmann, page 25.

(2852)

From Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark):

‘On page 47 of his book Af en skakstympers skriftemål Harald Enevoldsen relates the following story from a simultaneous display by Aron Nimzowitsch in 1923, in which Harald and his older brother Jens took part (they were aged 16 and 13 respectively):

“The way he handled the pieces was somewhat peculiar. He did not use the first, second and third fingers as we did, but the second, third and fourth. This – as it seemed – very sophisticated manner of moving the pieces we copied immediately, and I use it even today.”

On page 65 of Alt om skak (Odense, 1943) there is a picture of Alekhine giving a simultaneous display in Copenhagen in 1935. It is clear that he is moving the pieces in a similar way:

The question is whether both Nimzowitsch and Alekhine had this peculiar habit or whether Enevoldsen was mixing up the two. Any other evidence?’

(3055)

This position (White to move) occurred in a game between Nimzowitsch and Rosit in a simultaneous exhibition (in Riga, it would seem) against 21 players on 25 July 1918 and was discussed as follows by Nimzowitsch on page 210 of the September 1918 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

‘With his last move (…Rg7-g6) Black gave me the opportunity to bring about a pawn ending; however, despite the extra pawn this could not have been won, and I therefore first played 1 c4! My opponent, who had no forebodings, contentedly replied 1…Kg7 in order, after the further moves 2 Rxg6+ fxg6 3 Rxf8 Kxf8, to feel safe and happy in the resulting pawn ending. But, with the power of fate … 4 c6! bxc6 (forced) 5 b5! and Black resigned, as the passed a-pawn will advance inexorably. After 2…Kxg6 (instead of 2…fxg6) the following interesting play could have occurred: 3 cxd6 cxd6 4 Rd1 Rd8 5 c5 Kf6! 6 Kf2 Ke7 7 Kf3! dxc5 8 Rxd8 Kxd8 9 bxc5 Kc7 10 Kg4 Kc6 11 Kf5! Kb5! 12 Kxe5 Kxa5 13 Kf6 Kb4! (not to b5, because the e-pawn would then queen with check) 14 Kxf7 a5 15 e5 a4 16 e6 a3 17 e7 a2 18 e8(Q) a1(Q) 19 Qe4+ Kxc5 20 Qxb7 and White must win.’

(3386)

A prominent chessplayer who succumbed to cholera was Elijah Williams. To quote R.N. Coles on page 299 of the September 1954 BCM:

‘The summer of 1854 in London was overshadowed by a great epidemic of cholera, which out of a population of two-and-a-quarter million claimed over 3,000 deaths a week. The well-known chess master Elijah Williams, himself a doctor, was actually playing in the Divan one day in September when the disease attacked him ...’

It may be mentioned in passing that the entry on Williams in Harry Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977 and Harmondsworth, 1981) duly recorded that he died in 1854 but carelessly suggested that he was still writing his chess column in The Field three years later.

In the chapter ‘Ahead of Their Time’ in The Chess Companion (New York, 1968) Irving Chernev declared himself intrigued by Williams’ performance at London, 1851. From page 184:

‘Was his prolonged thinking part of a plan to infuriate his opponents? Or was it because he was slowly evolving a new system of play?

The terms “Double Pawn Complex” and “Zugzwang” could have had no meaning for Williams, but here, in two games [against Löwenthal and Staunton], we have this Nimzowitsch of a hundred years ago demonstrating these concepts.’

Chernev’s item originally appeared as an article on page 340 of the November 1955 Chess Review. We wonder if other writers have attempted to back up his theory, although nothing particularly helpful has yet been found by us in Williams’ book Horæ Divanianæ (London, 1852) or in other sources.

(3764)

Tim Harding (Dublin) sends the following item by T.B. Rowland from the Dublin Evening Mail of 29 October 1896:

‘An Infant Prodigy. An infant chess prodigy has been discovered in the person of Master Aron Niemzowitch, the nine-year-old son of a merchant of Riga, in Southern Russia [sic]. The following short game, played recently, is a specimen of his play: 1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qd8 4 Nf3 f5 (This is of course a weak move ...) 5 Bc4 Nc6 6 O-O Qd6 7 d3 Qb4 8 Be3 Qxb2 9 Nd5 Kd8 10 Bc5 b6 11 Rb1 Qxb1 12 Qxb1 bxc5 13 Ng5 Ne5 14 f4 h6 15 fxe5 hxg5 16 Ne3 f4 17 e6 fxe3 18 Rxf8 mate. (Black’s play is weak throughout, but the remarkable part of this little game is the able manner in which the boy takes full advantage of the weaknesses of his adversary. The St Petersburg Zeitung, in commenting on the above game, remarks, “We need no longer look to America for our chess prodigies”.)’

Mr Harding adds:

‘How many intermediaries there may have been between Rowland and the Petersburg paper I cannot say.’

One early publication of the score was in the Deutsches Wochenschach, 4 October 1896 (page 373). As far as we know, it is the only extant game by Aron Nimzowitsch from the nineteenth century.

(3859)

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks if this is the same game that Nimzowitsch mentioned on page 8 of his autobiographical booklet Kak ya stal grosmeysterom (Leningrad, 1929), where he affirmed that his first published score appeared in the Rigaer Tageblatt and that he was eight and a half at the time (i.e. circa May 1895):

(5276)

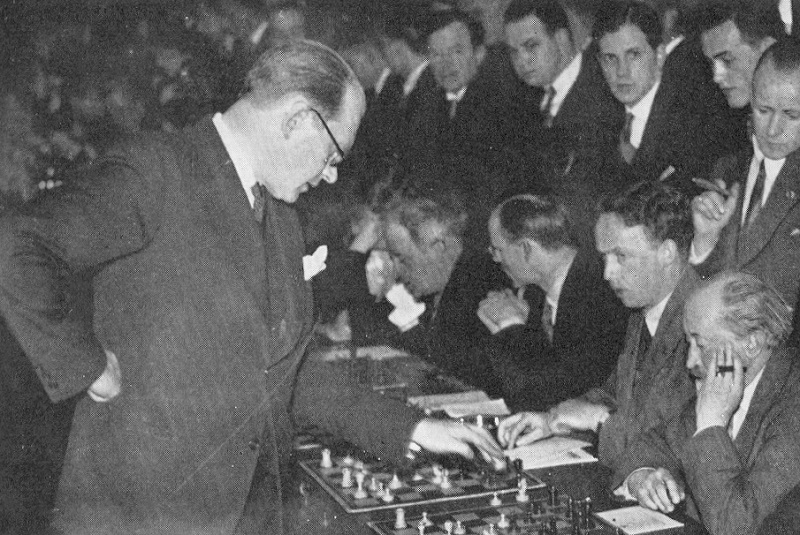

A group photograph from London, 1927:

Seated from left to right: F.J.

Marshall, W. Winter, E. Bogoljubow, A. Nimzowitsch, W.A.

Fairhurst, S. Tartakower.

Standing: W.H. Watts, M.E. Goldstein, H. Kmoch, M. Vidmar, R.C.

Griffith, Sir George Thomas, E. Busvine, F.D. Yates, J. Schumer,

E. Colle, V. Buerger, R. Réti

(3959)

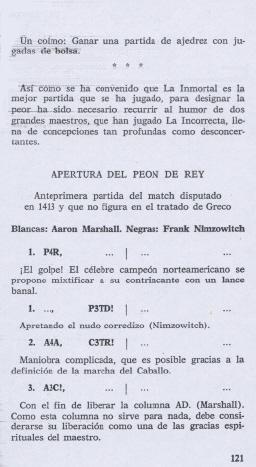

C.N. 4772 dealt with the famous Nimzowitsch v Sistemsson parody, and now Javier Asturiano Molina mentions a fantasy game between ‘Aaron Marshall’ and ‘Frank Nimzowitch’: 1 e4 a6 2 Bc4 Nh6 3 Bb3 Nf5 4 Be6 Na7 5 Qh5 Resigns 6 Drawn.

It was published on pages 121-122 of Ajedrología by Julio Ganzo (Madrid, 1971):

Had the spoof already been published elsewhere?

(4842)

Javier Asturiano Molina asks about an article by Alekhine in Skakbladet after Nimzowitsch’s death.

C.N. 1931 mentioned the tribute, which was published in the May 1935 issue of the Danish magazine:

(5275)

Addition on 5 July 2025:

In his ‘TheArticle’ piece of 5 July 2025, Raymond Keene reports learning of Alekhine’s ‘virtually unknown obituary’ of Nimzowitsch (Skakbladet, 1935). He naturally does not mention that the complete text has been available online (C.N. 5275) since November 2007.

That complete Nimzowitsch Memorial Issue of Skakbadet (May 1935) is available online.

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) has sent us a photograph taken by him of the Nimzowitsch-Enevoldsen ‘double grave’ in Copenhagen:

Our correspondent has also provided a photograph of the building in Copenhagen where Nimzowitsch lived (Øster Farimagsgade 11, second floor):

(4307)

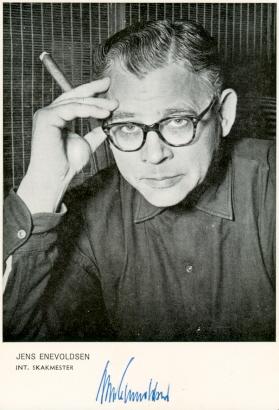

Phil Bourke (Blayney, NSW, Australia) asks why the two masters share the same resting place.

The matter was discussed on page 11 of Schaakgraven (the booklet mentioned in C.N. 4452). That publication relates that Nimzowitsch described Enevoldsen as ‘the hope of Danish chess’ after losing to him in the Copenhagen, 1933 tournament. Enevoldsen died in 1980, and in his will he expressed a wish to be buried alongside Nimzowitsch. The Danish Chess Union, the owner of the plot, acceded.

Per Skjoldager informs us:

‘Enevoldsen’s obituary by Poul Hage in Skakbladet, July 1980, pages 99-102 does not mention the matter, but I have checked the facts with Steen Juul Mortensen, who was the President of the Danish Chess Union in 1980. He confirms that Enevoldsen wanted to be buried alongside Nimzowitsch. His family made a contribution to the fund.

Nimzowitsch, for his part, had no family in Denmark when he died, in 1935. A number of chess friends created a fund to care for his grave, and the fund still exists today, administered by the Danish Chess Union.

As noted by Hage in the above-mentioned obituary in Skakbladet, Enevoldsen was a great admirer of Nimzowitsch, and they became friends in 1933. On page 150 of his autobiography 30 år ved skakbrættet (Copenhagen, 1952) Enevoldsen wrote about his victory over Nimzowitsch at Copenhagen, 1933 (my translation from the Danish):

“As you can imagine, the waves rose high when Nimzowitsch turned over his king. The master removed his glasses and wiped away the perspiration from his brow, stood up and disappeared. From all sides people shook hands with me and slapped me on the back. My elderly mother, who was a spectator that particular day, was as moved as when she became a grandmother ...

A few minutes later Nimzowitsch came back as calm and composed as would be expected. As a good sportsman he offered me his hand and thanked me for the game.

From that day on, he had tremendous respect for my play and never again regarded me with the usual lack of interest. In fact, we began to appreciate each other. Unfortunately, this lasted for only the two years that he had still to live. I am sure that he would have been happy to see the many games that I have played since then in his spirit and in accordance with his principles.”’

(5776)

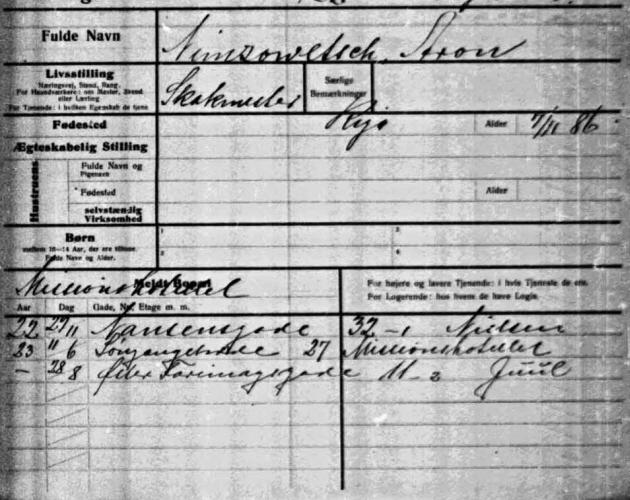

Philippe Kesmaecker (Maintenon, France) has found the above document at the Danish Politietsregisterblade website.

Per Skjoldager, the co-author of a forthcoming book on Nimzowitsch (see C.N.s 7108 and 7310), informs us:

‘This record is of great importance. It shows the dates when Nimzowitsch registered his arrival with the Danish police and specifies:

- Full name: Aron Nimzowitsch. Occupation: chess master. Born in Riga on 7 November 1886.

- On 29 November 1922 he moved to Nansensgade 32, first floor, his landlord being named Nielsen.

- On 11 June 1923 he moved to the Missionshotellet (Missionary Hotel) at Løngangstræde 27.

- On 28 August 1923 he moved to Øster Farimagsgade 11, second floor, where his landlady was Miss Juul.’

Mr Skjoldager has provided two photographs:

Nansensgade 32 is on the left of the Café Stjernen

Øster Farimagsgade 11 is on the right, behind the pedestrian.

(7647)

Noting that Aron Nimzowitsch included in his books a few of his correspondence games, Javier Asturiano Molina asks how many games the master is known to have played by post.

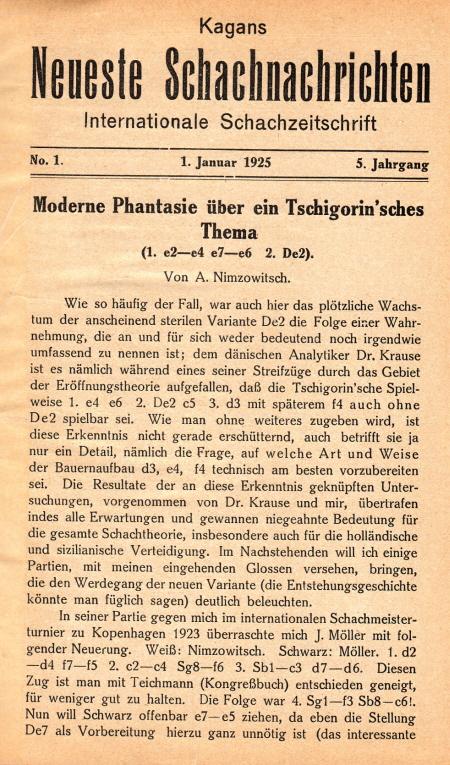

Readers’ assistance will, as ever, be welcome. To make a start, we note that Nimzowitsch gave victories over G. Fluss in both My System (game dated 1913) and The Praxis of My System (game dated 1912-13), while the latter book also had a 1924-25 game against O.H. Krause. On pages 429-430 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 October 1925 Nimzowitsch presented the first 18 moves of a correspondence game he was playing against V. Edman. A postal game lost by Nimzowitsch to K. Bētiņš in a match dated 1911-13 was published on pages 55-56 of the March 1965 Chess Life.

(4671)

We turn now to blindfold games by Nimzowitsch. There is the familiar brilliancy against Jokstad, played in Bergen in 1921 and annotated by Nimzowitsch on pages 161-162 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 April 1925, but how many others are known?

(4685)

C.N.s 3079 and 3251 (see pages 326-327 of Chess Facts and Fables) discussed a quote attributed to Teichmann, and now we note that Fred Reinfeld also gave it on page 129 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess (New York, 1960):

‘It took Nimzowitsch 20 years of tireless preaching to achieve acceptance. So great a master as Teichmann commented dourly that “in the first place there is no Hypermodern School, and in the second place Nimzowitsch is its founder”. This was a more or less polite way of saying that Nimzowitsch was crazy.’

That last remark of Reinfeld’s seems far-fetched, and it is unclear why he affirmed that Teichmann made the remark ‘dourly’.

Aron Nimzowitsch

Reinfeld on Nimzowitsch can be a strange spectacle. For example, on that same page he wrote: ‘By the time Nimzowitsch was 20, he had perfected his system.’ In his revised edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System (Philadelphia, 1947) Reinfeld wrote (page xxi) that ‘by 1906, when he was only 20, Nimzowitsch had definitely become a master of the very first rank’.

(5006)

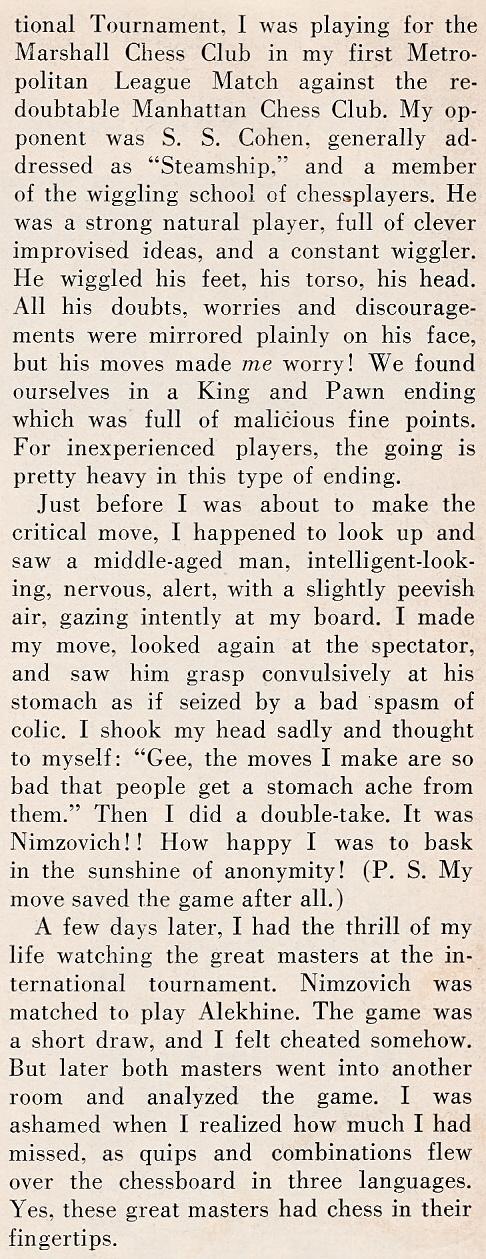

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) asks what facts are available concerning the well-known story about Nimzowitsch lamenting ‘Why must I lose to this idiot?’.

It was related by Hans Kmoch in his article on Nimzowitsch available online at the Chess Café:

‘On another occasion, in Berlin, having missed the first prize by losing to Sämisch, Nimzowitsch got up on a table and shouted, “Why must I lose to this idiot?” This story was told to me by the idiot himself.’

An article by Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld entitled ‘Unconventional Surrender’ on page 55 of the February 1950 Chess Review specified that the occasion was a rapid transit tournament:

‘A man mounting a table, however, and yelling at the top of his voice, “Why must I lose to this idiot!” (“Gegen diesen Idioten muss ich verlieren!”) would be following the example of Nimzowitsch, who thus vented his rage – after losing in the last round of a great rapid transit tournament in Berlin and so missing first prize.’

The tournament in question has yet to be identified.

(5019)

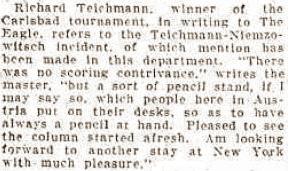

Aron Nimzowitsch (Schweizerische Schachzeitung, May-June 1931, page 67)

Justin Horton (Huesca, Spain) comments that many Internet pages place Nimzowitsch’s alleged lament about losing to ‘this idiot’ (Sämisch) not in Berlin, as stated by Kmoch, but at Baden-Baden, 1925.

Half-way through that tournament Nimzowitsch did indeed lose to Sämisch, but what evidence exists that such an incident occurred there?

(6718)

C.N. 5019 quoted from an article by H. Kmoch and F. Reinfeld on page 55 of the February 1950 Chess Review:

‘A man mounting a table, however, and yelling at the top of his voice, “Why must I lose to this idiot!” (“Gegen diesen Idioten muss ich verlieren!”) would be following the example of Nimzowitsch, who thus vented his rage – after losing in the last round of a great rapid transit tournament in Berlin and so missing first prize.’

We mentioned that the tournament in question had not been identified.

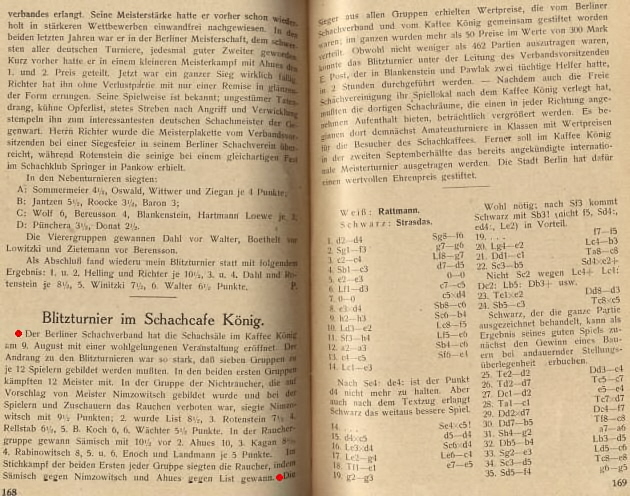

Now, Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) draws attention to pages 168-169 of Schachwart, September 1928:

The magazine states that for the rapid transit tournament in Berlin two preliminary groups were formed: non-smokers (Nimzowitsch being the victor, ahead of List) and smokers (Sämisch finished ahead of Ahues). In the play-off games, the smokers were victorious: Sämisch defeated Nimzowitsch, and Ahues won against List.

(8420)

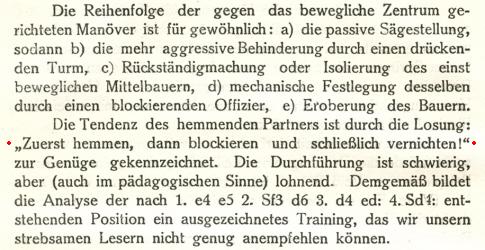

A fresh addition to our feature article on ‘The Most Famous Chess Quotations’ is Nimzowitsch’s dictum ‘First restrain, next blockade, lastly destroy’. It is certainly famous, yet we are struck by how seldom it is to be found on the Internet. Moreover, not a single webpage consulted by us gives the source (My System), and we found no instance online of the original German (‘Zuerst hemmen, dann blockieren und schließlich vernichten’).

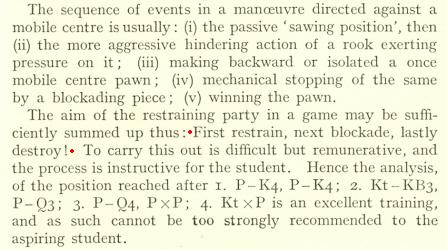

Below, to provide the context, is the full passage as it appeared in the first German and English editions (Berlin, 1925, page 246 and London, 1929, page 181):

It was in the section entitled ‘Doppelbauer und Hemmung’/‘The Doubled Pawn and Restraint’. Page numbers vary, but in the later editions of My System in our collection the reference is page 133, 151, 207 or 217. The last of these relates to the translation published by Quality Chess, Göteborg in 2007, which had a slightly different wording: ‘First restrain, then blockade and finally destroy.’

(5557)

The conclusion to the feature article The Termination:

Our Preface to Chess Explorations (1996) commented that Chess Notes was ‘born from the stark realization that the beaten track of chess literature was bestrewn with fallacies, guesswork and hearsay’ and that C.N. attempted ‘to clear away some of the deadwood and supplant it with a garland of more reliable material, founded on proper documentation’. With the Termination, much deadwood has been cleared away, but the supplanting process is slow and difficult.

To set the public record straight, a methodical approach can help: rebut misinformation and speculation, staunch their propagation, piece together the truth. First destroy, next blockade, lastly rebuild.

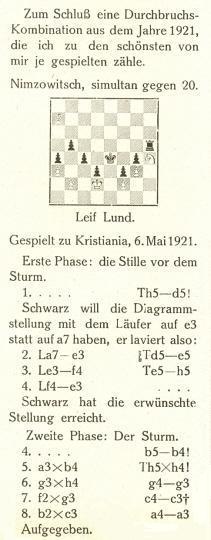

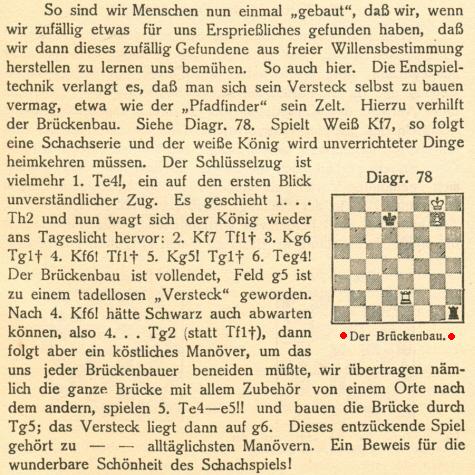

We are still looking for the full game-score of Lund v Nimzowitsch, Kristiania, 6 May 1921 (in a simultaneous display against 20 players). At present we have only the conclusion, as annotated by Nimzowitsch on page 164 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 April 1925:

(5081)

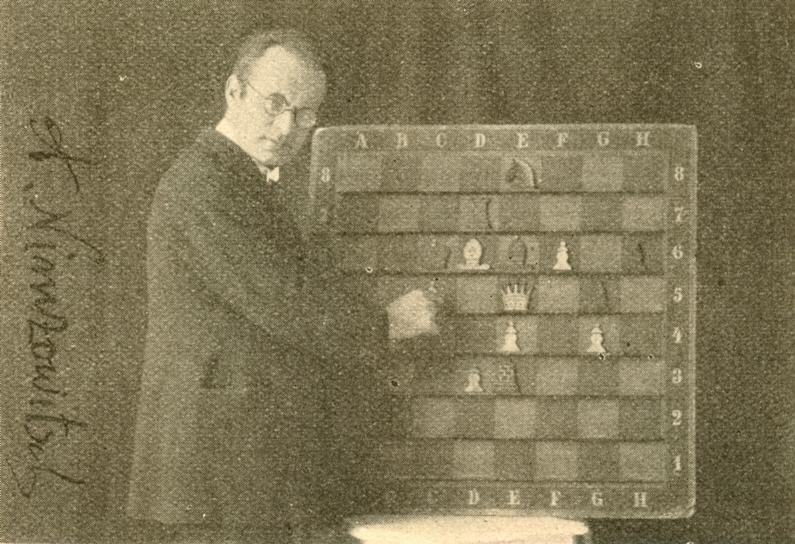

This photograph was published on page 10 of the American Chess Bulletin, January 1927. Does the board position come from a known game?

(5130)

Further to C.N. 5457, regarding the Benko Gambit, Tim Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) comments that if ‘general ideas’ is taken to mean that Black sacrifices a queen’s-side pawn for pressure on the opened files, the game Nimzowitsch v Capablanca, St Petersburg, 1914 may be regarded as an early model.

We add that Alekhine made a similar point about that game (describing it as ‘sensational’) in his notes to van Scheltinga v Opočenský, Buenos Aires, 1939. See pages 165-167 of Gran Ajedrez (Madrid, 1947) and pages 200-202 of 107 Great Chess Battles (Oxford, 1980).

(5461)

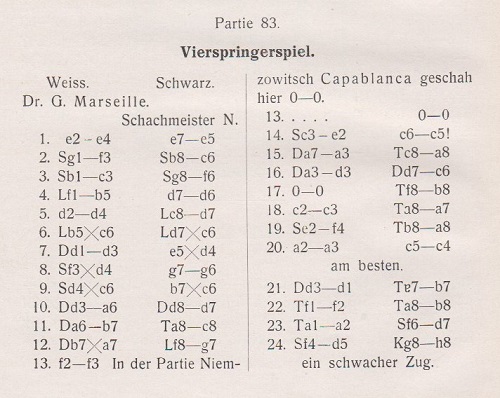

Wanted: information about a game published on pages 104-105 of Schachmeisterpartien des Jahres 1914 (volume two) by Bernhard Kagan (Berlin, 1915):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 d6 5 d4 Bd7 6 Bxc6 Bxc6 7 Qd3 exd4 8 Nxd4 g6 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 Qa6 Qd7 11 Qb7 Rc8 12 Qxa7 Bg7

13 f3 O-O 14 Ne2 c5 15 Qa3 Ra8 16 Qd3 Qc6 17 O-O Rfb8 18 c3 Ra7 19 Nf4 Rba8 20 a3 c4 21 Qd1 Rb7 22 Rf2 Rab8 23 Ra2 Nd7 24 Nd5 Kh8 25 Be3 Ne5 26 Nb4 Qb5 27 a4 Qe8 28 a5 Rxb4 29 cxb4 Nd3 30 a6 Nxb4 31 Ra3 Nd3 32 Rxd3 cxd3 33 Qxd3 Ra8 34 b4 h6 35 Ra2 Kh7 36 ‘Dd3-a5’ and White won.

The first note mentions the intriguing duplication of the opening 12 moves of Nimzowitsch v Capablanca, St Petersburg, 1914 – game 25 in My Chess Career and, as mentioned in C.N. 5461, a game described by Alekhine as ‘sensational’.

A detail regarding the two volumes of Kagan’s work (Berlin, 1914 and Berlin, 1915): the respective title pages had the spellings Schachmeisterpartieen and Schachmeisterpartien.

(9535)

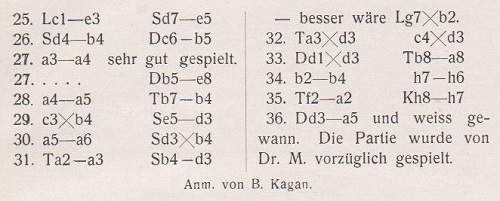

This group photograph (Copenhagen, August 1934) was published on page 318 of Schackvärlden, September 1934. It was taken seven months before Nimzowitsch died, and we wonder whether it is the last picture of him.

(5478)

Per Skjoldager writes:

‘The picture published in Schackvärlden in 1934 is surely one of the last of Nimzowitsch – but not the last. The distribution of prizes took place before the banquet (as reported on page 319 of the Swedish magazine), and it may be assumed that the picture in C.N. 5478 was taken on that occasion. The caption reads: “Gruppbild av pristagarna” (Group photograph of the prize-winners).

I have a photograph of the tournament banquet at the Nimb restaurant which must have been taken a few hours later. Nimzowitsch is sitting at the main table on the left. On his right is I. O. Pedersen, the President of the Copenhagen Chess Federation.’

(5482)

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) draws attention to this photograph on page 197 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943):

Our correspondent notes that Nimzowitsch is standing in the background. He also suggests that, in the photograph in C.N. 5482, the second person to Nimzowitsch’s right is Gideon Ståhlberg.

(5484)

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) quotes an extract from an article by Hans Kmoch about Nimzowitsch which mentions Hans Frank:

‘My last meeting with Nimzowitsch was also the longest. It took place in 1934, when we were both following the second Alekhine-Bogoljubow world championship match as reporters. The games of the match were scheduled to be played in many parts of Nazi Germany – unfriendly territory for a Jew and not particularly safe for a Gentile either, in view of the tensions immediately preceding Hitler’s bloody purge of his political enemies, among them Ernst Röhm.

Nimzowitsch considered himself protected by three consulates: the Latvian because of his birthplace, the Danish because of his residence, and the Dutch because some of his reports were going to a newspaper in Holland. He boasted of this protection even to Reichsminister Hans Frank, who at that time was in charge of the “protection” of art and later became the governor of Nazi- occupied Poland. Frank followed a few games of the match and sometimes chatted with the masters and reporters, including Nimzowitsch. He even invited the whole chess troupe to his villa for lunch. The Jews Mieses and Nimzowitsch were included in the invitation, but only Nimzowitsch showed up. At the luncheon he demonstrated his usual persecution mania by complaining first about a dirty plate and then about a dirty knife. The Reichsminister, seated directly opposite him, pretended not to hear.

Hans Frank

In Kissingen, where some of the match games were played, I was a guest in the same hotel at which I had stayed during the tournament in 1928. Overcrowded then, it was empty in 1934. At dinnertime, when the restaurant should have been crowded, there were only four people in the room: my wife and I, and, at another table, Frank and an elderly man who I later learned was the composer Richard Strauss. The sinister emptiness of that dining room, which the hotel manager attributed to “bad economic conditions”, should have been a forewarning, but the Nazi leaders understood nothing. Frank himself failed to understand what was going on under his governorship in Poland. He became known as “the butcher of Poland”, and for his war crimes he was hanged in Nuremberg.’

If any reader has Nimzowitsch’s reports on the 1934 world championship match we should be grateful to know whether they contain points of particular interest.

(5547)

Aron Nimzowitsch

On pages 128-129 of The World’s Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1951) the following appeared regarding Nimzowitsch:

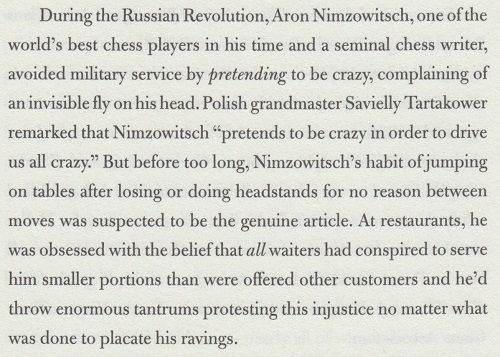

‘Many other eccentricities are reported of him. At one time a doctor ordered him to do calisthenics; he began to do them in the tournament room. During a particularly difficult situation once, he went to a corner and stood on his head.

Were it not for these unfortunate aberrations, Nimzowitsch might well have become world champion.’

And from page 66 of Fine’s The Psychology of the Chess Player (New York, 1967):

‘Towards the end of his life, (1929-35), the émigré Russian master Aron Nimzowitsch was advised by his physician to take more exercise. He thereupon proceeded to act on this advice by performing calisthenics during actual tournament play. When it was not his move, he would go off to his corner and do deep knee bends or the like. Several times he astonished spectators by standing on his head. In spite of these aberrations, Nimzowitsch scored his greatest successes around this period.’

Whether any corroboration exists for these claims that Nimzowitsch (‘once’ or ‘several times’) stood on his head we do not know, but when George Botterill mentioned the subject on page 461 of the December 1974 BCM he described Fine as ‘scurrilous’. We can add that the following was published on page 68 of the December 1946 CHESS, in an article by M.G. Sturm:

‘Another good method is to perform physical exercises on the floor. ... If anyone tries to stop you, quote Nimzowitsch, who attributed his success, at some tournament or other, to such a course of physical exercises.’

A further question is whether the story has any connection with the claim that Nimzowitsch ‘once’ broke his leg during a game of chess. This letter from Kester Svendsen was on page 101 of CHESS, January 1948:

(5548)

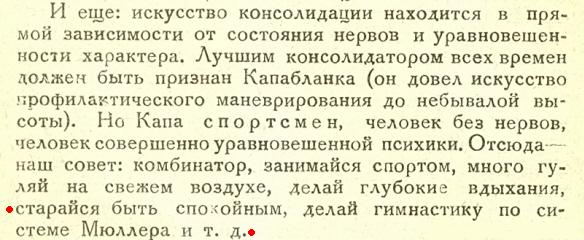

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) notes that page 24 of Nimzowitsch’s booklet Kak ya stal grosmeysterom (Leningrad, 1929) recommended the practice of gymnastics with ‘Müller’s system’.

Our correspondent identifies the book in question as Mein System 15 Minuten täglicher Arbeit für die Gesundheit by J.P. Müller, published at the beginning of the twentieth century.

(5552)

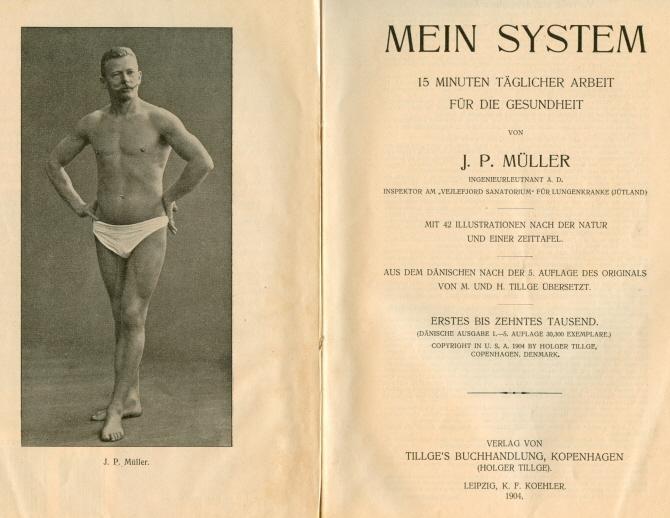

This is the work referred to by Nimzowitsch, as mentioned in C.N. 5552: Mein System 15 Minuten täglicher Arbeit für die Gesundheit by J.P. Müller (Copenhagen and Leipzig, 1904).

The book first appeared in Danish in August 1904, sold very well and was translated into various languages.

(5572)

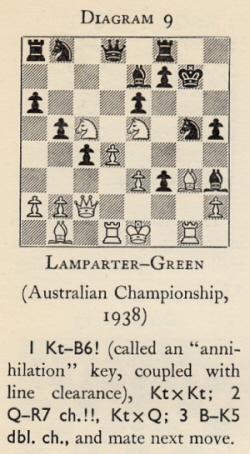

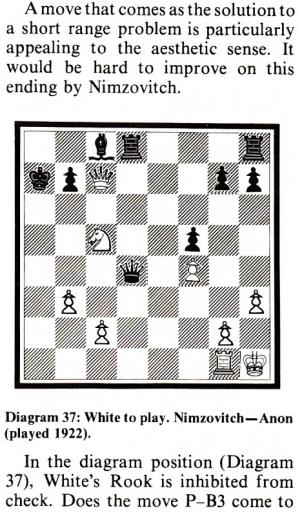

White to move

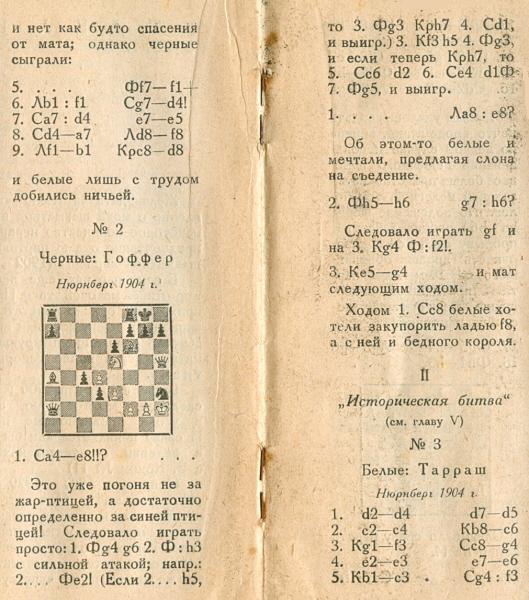

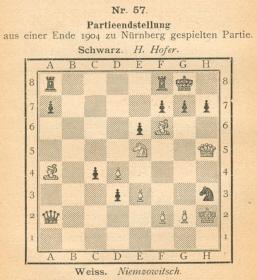

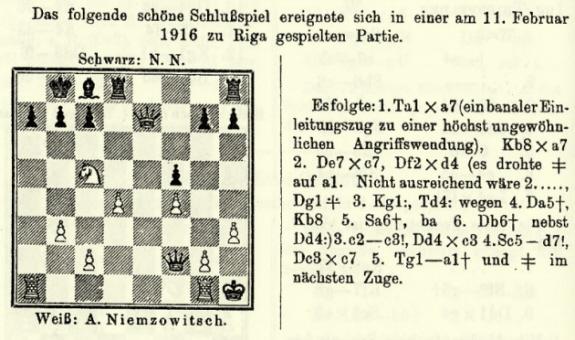

Javier Asturiano Molina asks about an early Nimzowitsch game with a spectacular finish (1 Be8), which the master published on pages 32-33 of his booklet Kak ya stal grosmeysterom (Leningrad, 1929):

The heading states that the game was played in Nuremberg in 1904 and that Black was ‘Hoffer’. We know of nothing to suggest that Leopold Hoffer was meant. When the position was given on page 62 of Heft 11 of the Baltische Schachblätter, 1908, Black was identified as ‘H. Hofer’, and the game was dated 1907:

We have never come across the full game-score.

(5604)

White to move

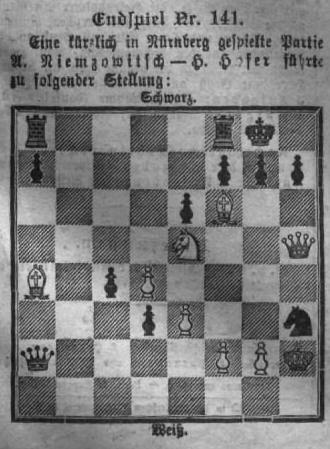

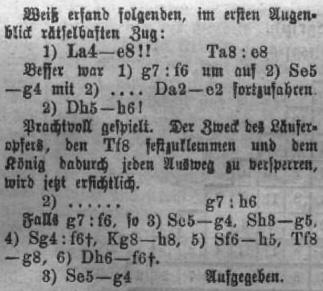

From Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany):

‘I have found the ending in two 1905 sources (Deutsches Wochenschach, 15 January, page 24, and L. Bachmann’s Schachjahrbuch für 1905, I. Teil, pages 90-91), so the date “1907” given in the Baltische Schachblätter is definitely wrong. Deutsches Wochenschach stated that the game was played “kürzlich in Nürnberg”, while Bachmann dated it as “Ende 1904 zu Nürnberg”. In both cases Black was named as “H. Hofer”. Additional analysis was published in the “Briefwechsel” on page 47 of the 29 January 1905 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach, showing that Black would have won after 2...gxf6 (instead of 2...gxh6) 3 Ng4 Qxf2.

Neither source gave the complete game.’

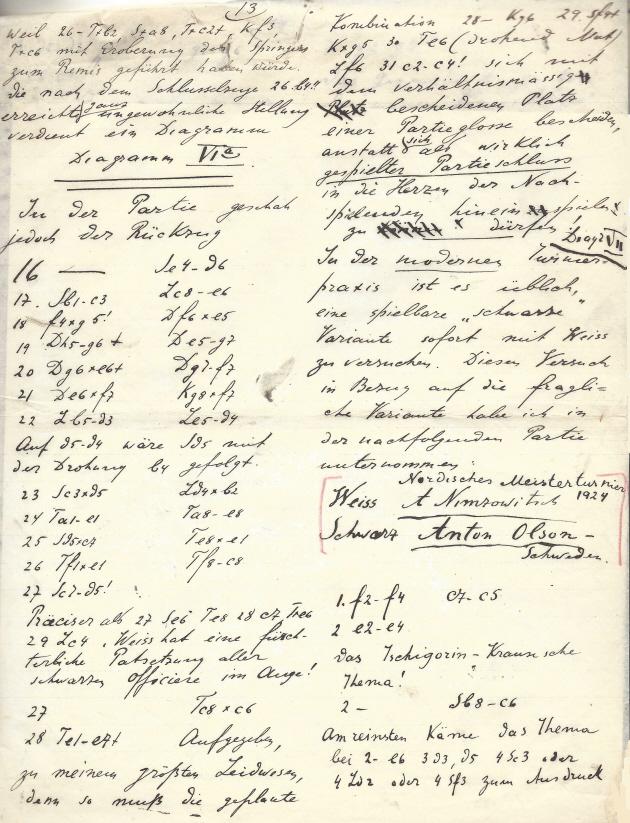

From page 90 of Schachjahrbuch für 1905, I. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1905):

(5610)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) writes:

‘Page 15 of the Düna Zeitung, 22 January (4 February) 1905 gave the conclusion of Nimzowitsch v Hofer:’

(8392)

From our feature article on The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by Nathan Divinsky (London, 1990):

‘Page 81 reports that Steinitz used the term hanging pawns, but page 144 states that Nimzowitsch introduced it.’

If the page references are replaced by 135 and 213, the comment of ours also applies to The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977). That is no great surprise, given that so much of Golombek’s book was repeated by Divinsky, without acknowledgement or care.

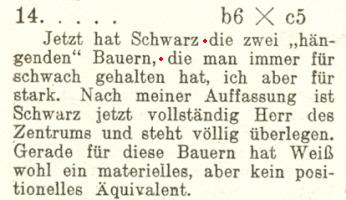

On the substantive matter of when, and by whom, the term ‘hanging pawns’ was first used, the earliest citation that we can currently offer (‘die zwei “hängenden” Bauern’) is on page 56 of Das Grossmeisterturnier zu St Petersburg by Siegbert Tarrasch (Nuremberg, 1914) after 14...bxc5 in Tarrasch’s notes to his game (as Black) against Nimzowitsch:

(5725)

Assertions in The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977) and The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by Nathan Divinsky (London, 1990):

Divinsky (entry on hanging pawns, page 81): ‘Steinitz used this term ...’

Divinsky (entry on Nimzowitsch, page 144): ‘Nimzowitsch introduced into chess terminology such phrases as ... “hanging pawns” ...’

The discrepancy in the Golombek book was pointed out by W.H. Cozens on page 400 of the September 1978 BCM but remained in the 1981 paperback edition (page 199 and page 308).

From page 98 of Pocket Book of Chess by Raymond Keene (London, 1988):

‘The term “hanging pawns” was coined by Wilhelm Steinitz, who was world champion from 1886 to 1894.’

In short, plenty of claims, contradictions and copying, but no corroboration.

So far, the earliest known instance (shown by Thomas Niessen in C.N. 9920) is dated 1902, i.e. post-Steinitz and pre-Nimzowitsch.

(9941)

See too Hanging Pawns in Chess.

Two fine photographs of Nimzowitsch and Réti which we have occasionally reproduced from pages 159 and 82 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943) prompt a question from Maurice Carter: bearing in mind that the chess sets and boards appear to be identical, on what occasion were the photographs taken?

(5933)

Zdeněk Závodný (Brno, Czech Republic) notes that the same photograph of Réti, although showing more of the board position, was published in the 11 June 1929 issue of the Czech magazine Letem světem.

(5938)

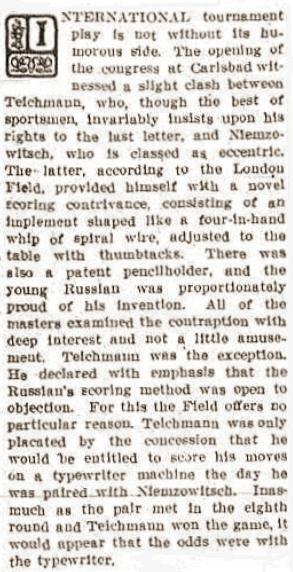

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) provides this cutting from page 11 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 7 September 1911:

(6515)

John Blackstone has found a follow-up item on page 2 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 19 October 1911:

(6540)

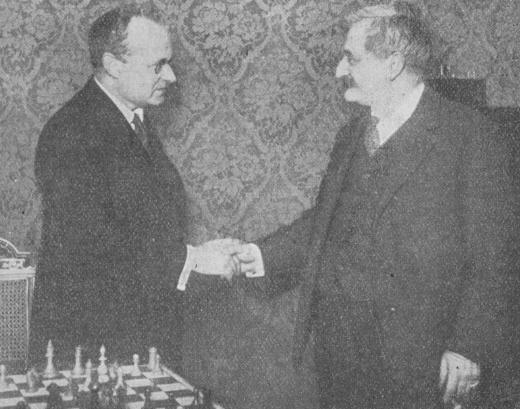

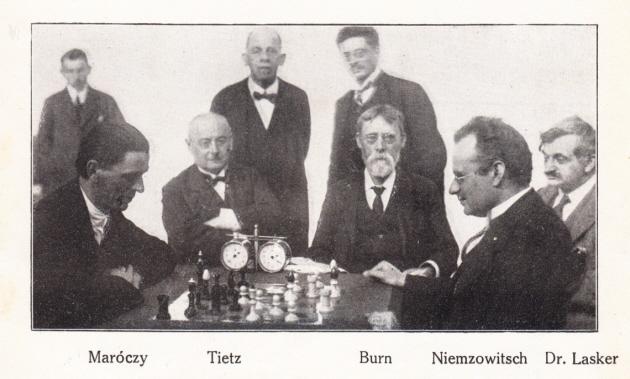

There follows an extract from our article on Emanuel Lasker Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by Richard Forster, Stefan Hansen and Michael Negele (Berlin, 2009):

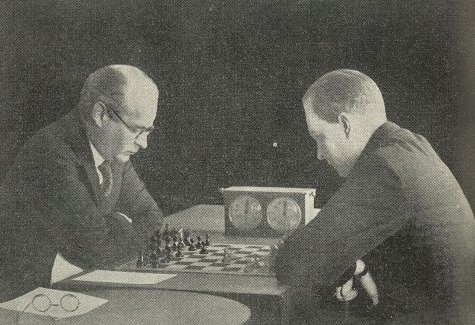

The photograph below, from page 1029, shows Lasker with Nimzowitsch during a tournament in Berlin in spring, 1928:

Another shot featuring Nimzowitsch (as well as Kmoch, Alekhine and Bogoljubow, during the 1934 world championship match) is on page 291:

See A Series of Books on Lasker.

Page 33 of The World Champions Teach Chess compiled by Y. Estrin and I. Romanov (London, 1988) quoted a comment by Nimzowitsch after Alekhine’s triumphs at San Remo, 1930 and Bled, 1931:

‘He makes short work of us as if we were little chickens.’

We are unaware of a Russian edition of the book, but the German version, Weltmeister lehren Schach (Hollfeld/Obfr., 1985), had put the following:

‘Er legt uns wie Grünschnäbel um.’

The most direct translation of Grünschnäbel is ‘greenhorns’ or, possibly, ‘whippersnappers’.

Nimzowitsch’s remark was quoted by Hans Kmoch in an article on Alekhine at the Chess Café:

‘At Bled, Alekhine’s superiority drove the proud Nimzowitsch to despair. When he resigned to the world champion after only 19 moves he was near tears. “It’s incredible”, he complained. “Only a few years ago we were all about equal”, he said, referring to the chess elite of that time, “but now he treats us like patzers.”’

Kmoch was present at the Bled, 1931 tournament. Page 53 of the English edition (Yorklyn, 1987) of his book on the event, translated by Jimmy Adams, had the following text in the introduction to the round in which the Alekhine v Nimzowitsch game was played:

‘Nimzowitsch could not recover from his astonishment. After taking both pawns, he left the board and, shaking his head, repeated several times, “He is treating us like patzers.”’

The words ‘He is treating us like patzers’ were also quoted, by Flohr, on pages viii-ix of the English book, in a 1976 article translated from 64.

The original edition of the Bled, 1931 tournament book (Leningrad, 1934) was a translation of Kmoch’s unpublished German text, which may or may not be extant. Below is the relevant passage, from page 53:

The quote attributed to Nimzowitsch is:

‘Он обращается с нами, как с желторотыми птенчиками.’

A literal rendering is ‘He treats us like yellow-beaked fledglings’. The term ‘yellow-beaked’ in Russian means young and inexperienced.

It is hoped that other sightings of the Nimzowitsch quote can be found. The unsatisfactory situation at present is that we have Estrin’s text in German but not the original Russian and Kmoch’s text in Russian but not the original German.

(6684)

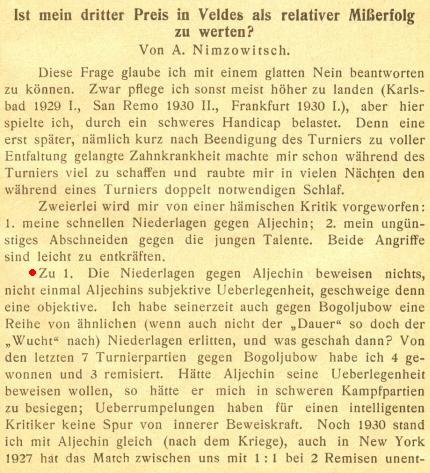

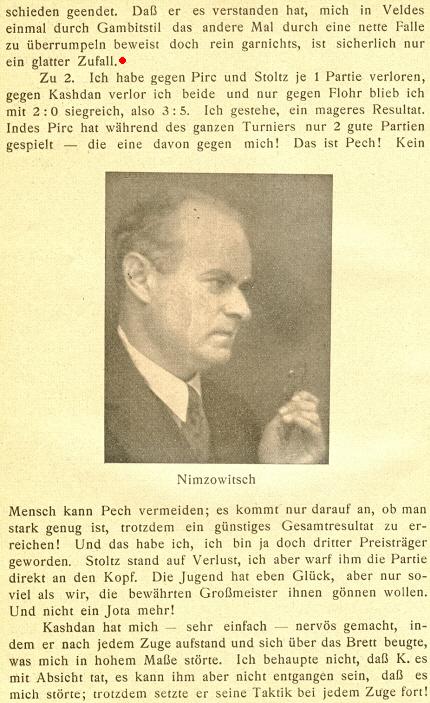

On pages 67-69 of the March 1932 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten Nimzowitsch wrote an article about whether his third place at Bled, 1931 (after Alekhine and Bogoljubow) was to be regarded as a relative failure:

In the passage marked with red Nimzowitsch states that his two defeats against Alekhine prove nothing. He mentions that although at one time he suffered a series of defeats against Bogoljubow, his latest score against him in tournament games is four wins, three draws and no losses. Nimzowitsch adds that as recently as 1930 (presumably 1920, since he also writes ‘after the War’) he stood equal with Alekhine; moreover, he had a tied result in his games with him at New York, 1927. Nimzowitsch’s conclusion is that Alekhine, to demonstrate his superiority, would have to defeat him in hard battles, whereas his two victories over him in the Bled tournament, one in gambit style and the other by catching him out with a pretty trap, proved absolutely nothing and were certainly pure chance.

(6695)

A passage from an article by Roberto Grau on San Remo, 1930 was quoted in C.N. 1041:

‘When Alekhine beat Nimzowitsch in such masterly style the first to congratulate him was the defeated man himself. This gesture by the aggressive Nimzowitsch is a token of his admiration for his opponent’s skill, and as he rose from the board he said in a loud voice, “Alekhine plays phenomenally”.’

Source: El Ajedrez Americano, March 1930, pages 66-69.

(7180)

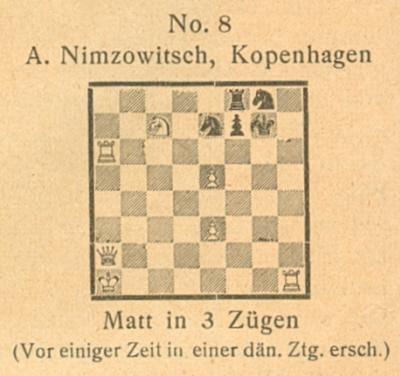

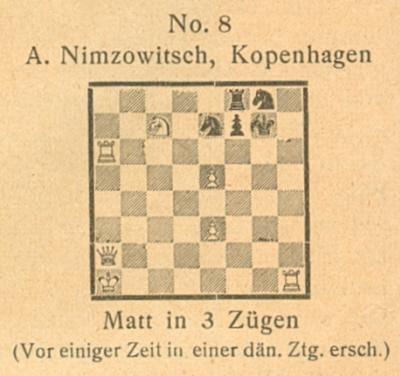

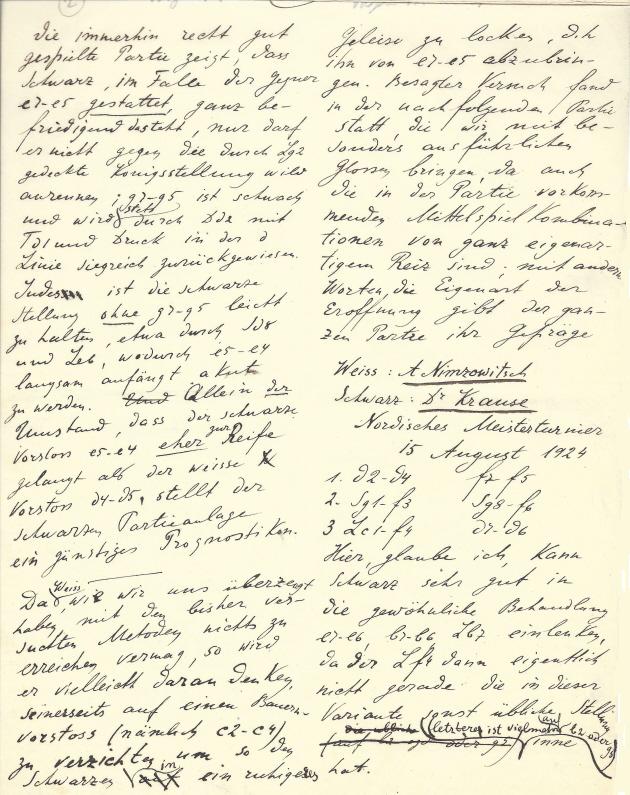

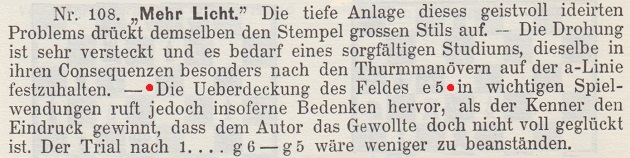

From page 70 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, March 1932:

Wanted: details about the composition’s prior appearance in a Danish publication, as mentioned in the caption.

(6696)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) notes that

Nimzowitsch’s composition was included on page 83 of Godehard

Murkisch’s book Rätselvolle Schachaufgaben (Munich, 1985),

the source being stated as the Baltische Zeitung, 1919.

White’s king was on c1, and not a1. Nikolai Brunni (Honolulu, HI,

USA) mentions that that same position is given online at a Nimzowitsch

page (‘Baltische Zeitung, 1918’). [The link is now

broken.]

(6700)

Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, March 1932, page 70

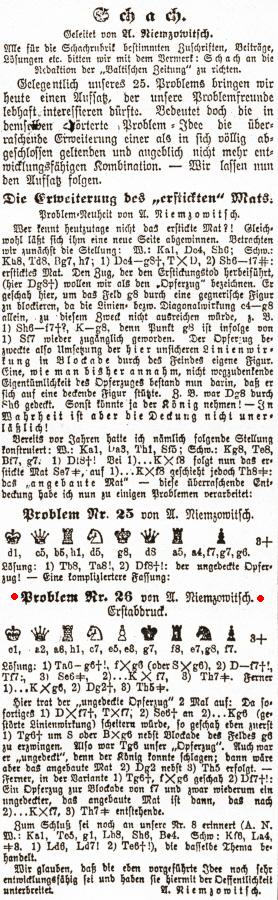

From Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany):

‘The mate in three was published in Nimzowitsch’s chess column on page 6 of the Baltische Zeitung of 11 December 1918, in an article dealing with smothered mate. (Note that the white king is on c1.)

A number of articles from Nimzowitsch’s column in that publication were reprinted in my article “Aaron Nimzowitsch und die Baltische Zeitung” in Kaissiber, October-December 2007, pages 54-65.’

(6706)

From page 109 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

‘Nimzowitsch described someone as “An amateur who played a weak enough game to enable him to conduct an important chess column”.’

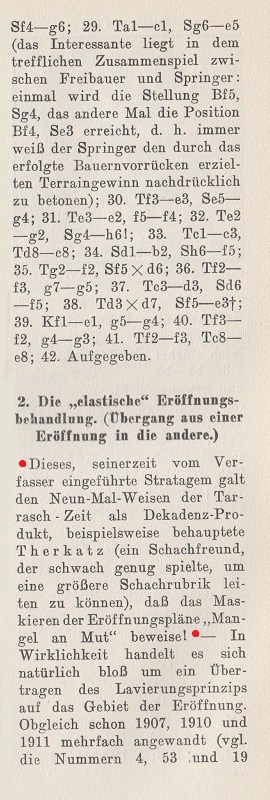

Chernev gave no further details, but the words appeared on page 261 of Nimzowitsch’s book The Praxis of My System (London, 1936). The translation, by J. du Mont, omitted the name of the columnist in question, but it had been given on page 180 of the original edition, Die Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930):

The name also appeared on page 154 of a recent English translation (by Ian Adams) of Nimzowitsch’s book, published under the title Chess Praxis (Glasgow, 2007):

The report of Wilhelm Therkatz’s death on page 12 of the January 1925 Wiener Schachzeitung stated that he had conducted the chess column in the Krefelder Zeitung for 26 years.

(6723)

From ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’ on the inside front cover of the October 1952 Chess Review:

As discussed in C.N. 6723, the columnist referred to by Nimzowitsch was Wilhelm Therkatz. From pages 180-181 of the 1930 edition of Die Praxis meines Systems:

What was the precise wording and context of the remark by Therkatz which Nimzowitsch had in mind?

From page 39 of the February 1925 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

(10707)

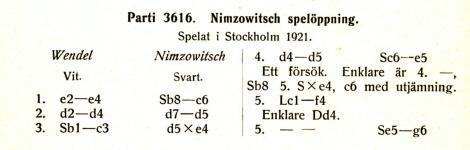

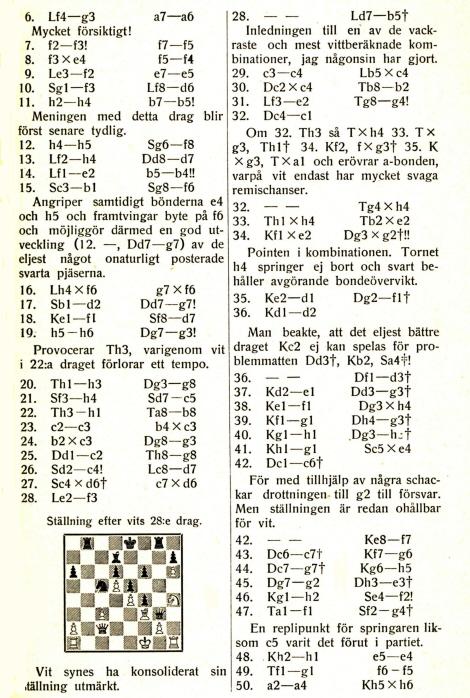

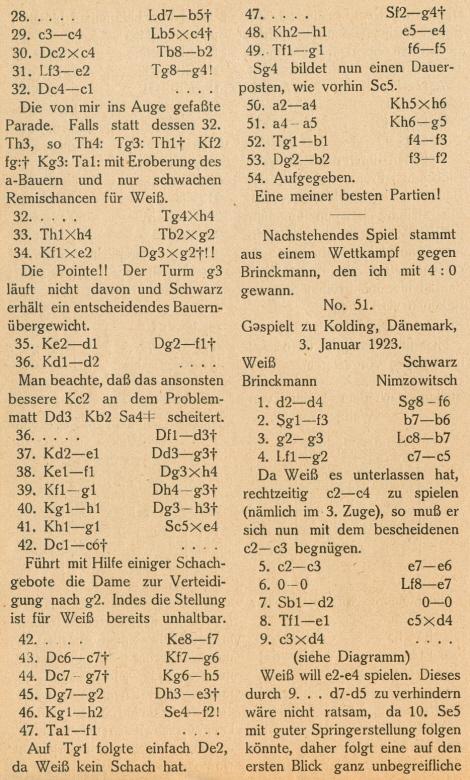

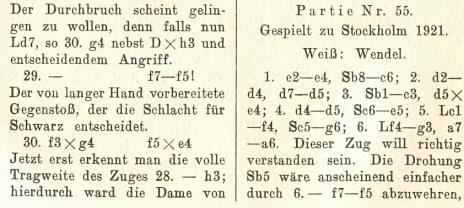

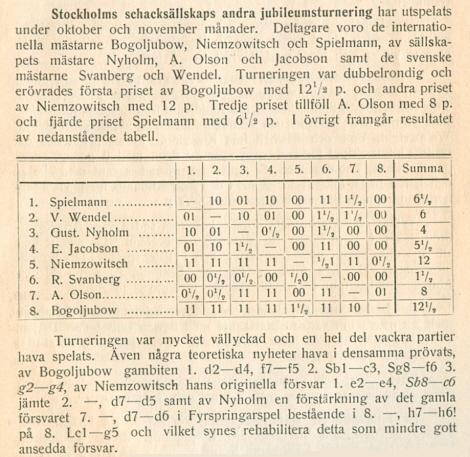

Javier Asturiano Molina asks for information about the exact occasion when the famous game Wendel v Nimzowitsch (‘Stockholm, 1921’) was played.

Nimzowitsch described it as ‘one of my best games’, and it has been widely printed and praised. For instance, on pages 6-8 of Irving Chernev’s The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) it appeared with the following introduction:

‘There are deep, dark and mysterious moves in this exotic game that could only have been produced by a strange, original genius.’

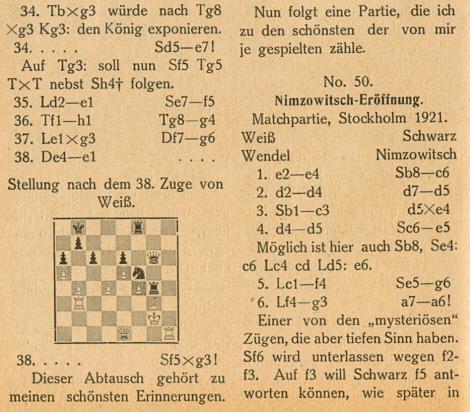

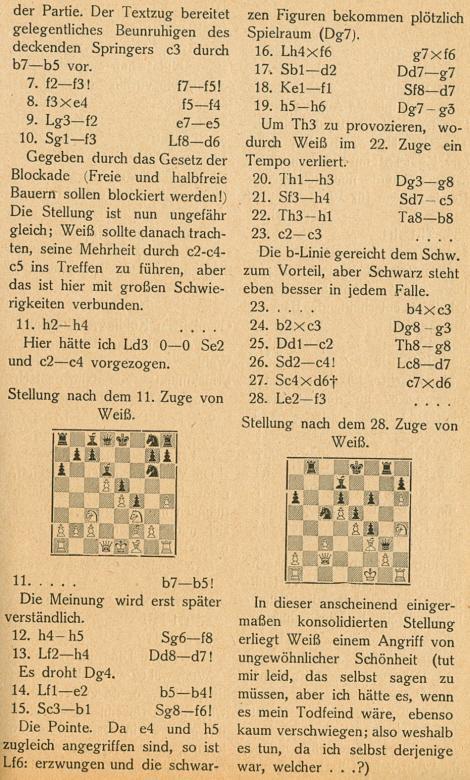

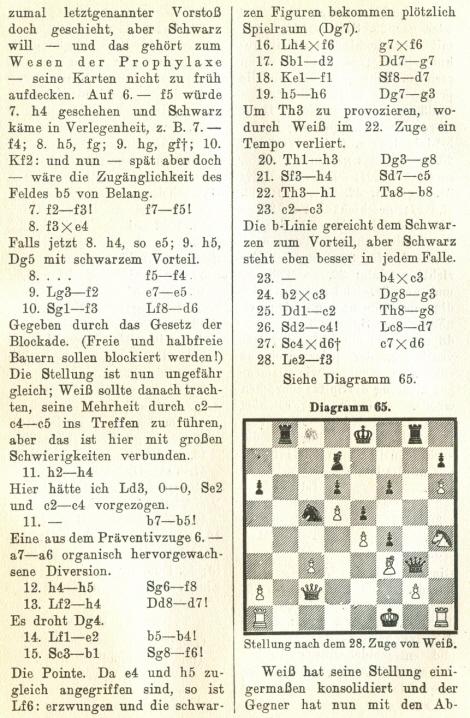

The game was published (headed ‘Stockholm, 1921’, but without further details) on pages 8-10 of the January-February 1922 issue of the Swedish magazine Tidskrift för Schack, with Nimzowitsch’s annotations:

Acknowledgement: Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) and Peter Holmgren (Stockholm).

A different set of notes by Nimzowitsch appeared on pages 148-150 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 April 1925:

In the German magazine the heading stated that it was a ‘match game’. There was no such reference in a third set of notes by Nimzowitsch, on pages 128-130 of his book Die Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930):

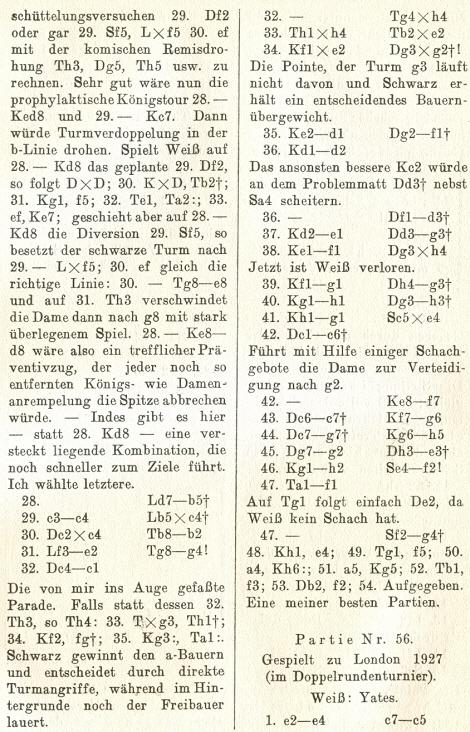

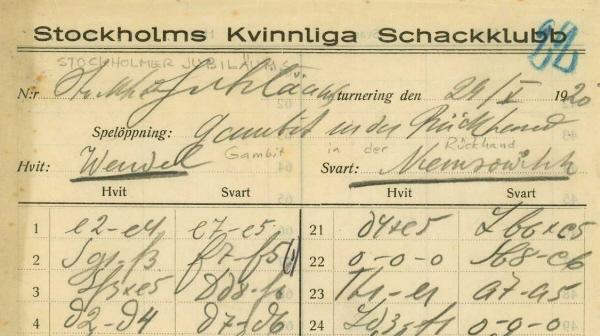

In none of these publications did Nimzowitsch identify White by more than his surname, but the player is almost certainly Verner Wendel (1893-1940), who has an entry in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia. He was active in Stockholm chess circles during the period in question and participated in a tournament in that city, with Nimzowitsch, in October-November 1920. From page 203 of the November-December 1920 Tidskrift för Schack:

That same issue had Nimzowitsch’s notes to games by Wendel against Olson and Spielmann, but neither of Nimzowitsch’s victories against Wendel in the tournament was given. Nor has any reference to a Nimzowitsch v Wendel match been found in the Swedish magazine or elsewhere.

It may thus be wondered whether the Wendel v Nimzowitsch game under discussion was, in fact, played in the Stockholm tournament of October-November 1920, and not in 1921 as stated by Nimzowitsch. In that case, though, Nimzowitsch could have been expected to publish ‘one of my best games’ in the Tidskrift för Schack of the time, i.e. together with his wins against Olson, Spielmann and Jacobson from the Stockholm, 1920 tournament (which he did annotate in the November-December 1920 edition of the magazine). However, as shown above, his notes to the Wendel v Nimzowitsch game were not published until the January-February 1922 issue.

If, therefore, the date 1921 for the Wendel v Nimzowitsch game is correct after all, an event in which it could have occurred remains to be identified.

(6719)

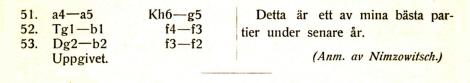

C.N. 6719 asked whether the Wendel v Nimzowitsch game under discussion (which began 1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5) was perhaps played in the double-round tournament in Stockholm, October-November 1920.

Maurice Carter, who has a book on Nimzowitsch in progress, informs us that that possibility can be discounted, given that he owns Nimzowitsch’s score-sheet of the game against Wendel in which Nimzowitsch was Black. The heading provided by our correspondent is shown below:

(6737)

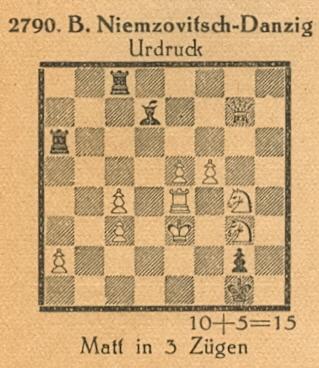

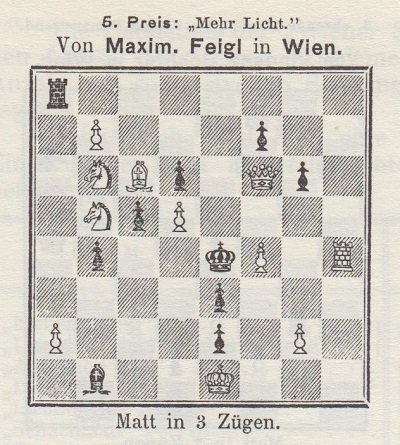

C.N. 2273 (see page 26 of A Chess Omnibus) asked for biographical information about the problemist B. Niemzowitsch and gave this mate-in-three from page 587 of Die Schwalbe, November 1933:

We have received the following from Per Skjoldager, who, as mentioned in C.N. 3506, is co-authoring with Jørn Erik Nielsen a book on Aron Nimzowitsch:

‘Aron Nimzowitsch had three younger brothers, and Benno (or Benjamin) was the youngest. He was born on 14 May 1896 (new style) and by the first of his two marriages he had a son, Isay-Erik (born in Berlin on 28 July 1928). Benno lived in Berlin for several years, before moving to Langfuhr, Danzig. He was a strong chessplayer as a boy but put his efforts into problem composition. Because of his Jewish background, he had to flee from the Nazis, and he finally went back to Riga. The Nazis killed the entire family in 1941.

Benno Niemzowitsch (photograph courtesy of Per Skjoldager)

In our collection we have more than 30 problems by Benno Niemzowitsch. For the most part they are self-mate compositions, but there are also a few direct-mate problems. His first composition on record was published in the Baltische Zeitung of 2 October 1918, in Aron Nimzowitsch’s chess column (“Erstabdruck”):

Mate in four

When this problem was given on page 95 of Skakbladet, June 1936 the pawn on g7 was missing, and the composition was ascribed to Aron Nimzowitsch.’

(6727)

Mr Skjoldager informs us that the Nimzowitsch book mentioned in the previous item is due to be published in 2011 and he adds:

‘An early game between Benjamin Blumenfeld and Aron Nimzowitsch, Berlin, 1903 (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nxc6 bxc6 6 Bd3 d5 7 e5 Ng4 8 O-O Qh4 9 h3 h5 10 Bf4 Bc5 11 Qd2 Rb8 12 Nc3 Rb4 13 Bg5 Qg3 14 hxg4 hxg4 15 Rfe1 Rh2 16 Bf1 Rh8 17 Bd3 Rh2 18 Bf1 Bxf2+ 19 Qxf2 Rh1+ 20 Kxh1 Qxf2 21 Re2 Qg3 22 Rd1 Bf5 23 Nxd5 cxd5 24 Rxd5 Rb8 25 e6 fxe6 26 Rxf5 Kd7 27 Rf7+ Kc6 28 Rxe6+ Kb7 29 Kg1 Resigns) can be found on the Internet, but we have not been able to trace a source for it.

We believe that it is probably a “real game”, partly because Nimzowitsch played this particular variation of the Scotch Game in his youth and partly because he was acquainted with Blumenfeld during his early years in Berlin. We have looked through all possible chess columns and all contemporary German periodicals, as well as Blumenfeld’s books, without success, but the game may have been published by him in a Russian/Soviet chess magazine. Can anyone find it?’

(6728)

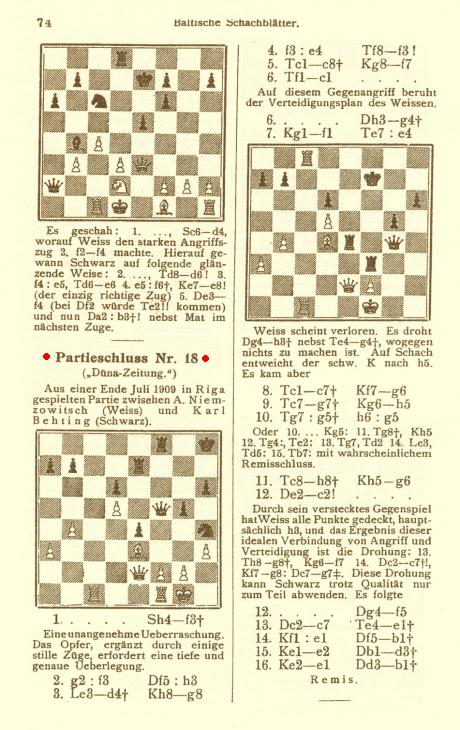

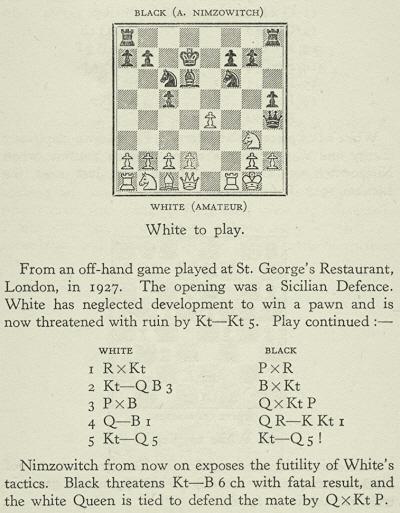

Javier Asturiano Molina asks whether the complete score of the drawn game Nimzowitsch v Behting, Riga, 1909 can be traced. Only the conclusion (from 1...Nf3+ to 15...Qd3+) was given by Nimzowitsch on pages 162-164 of the 1 April 1925 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten and on pages 246-247 of Die Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930). See also pages 352-354 of The Praxis of My System (London, 1936).

We have not found the full game but note that the last phase (ending with 16 Ke1 Qb1+) was published on page 74 of Heft 12 (dated 1910) of Baltische Schachblätter, which was co-edited by Nimzowitsch’s opponent, Carl/Karl Behting:

It may be remarked that in the ‘initial’ position Black’s knight is on h4 whereas Nimzowitsch placed it on e5.

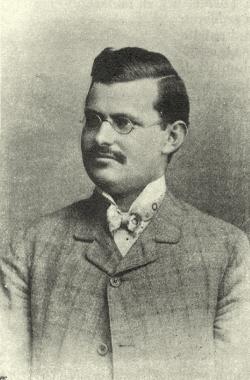

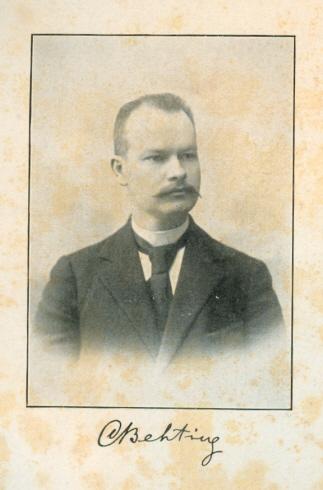

Carl/Karl Behting (Deutsches Wochenschach, 5 January 1908)

(6823)

Information would still be welcome concerning a game whose conclusion was given in C.N. 2526 (see page 49 of A Chess Omnibus), our source being pages 83-84 of Learn to play Chess by P. Wenman (Leeds, 1946):

(6962)

Maurice Carter reports that the full game-score was published in The Observer (London) of 25 March 1928:

N.N. – Aron Nimzowitsch1 e4 c5 2 Ne2 e5 3 f4 d6 4 fxe5 Nc6 5 Ng3 h5 6 exd6 Bg4 7 Be2 Bxd6 8 Bxg4 Qh4 9 Bd7+ Kxd7 10 O-O Nf6 11 Rxf6 gxf6 12 Nc3 Bxg3 13 hxg3 Qxg3 14 Qf1 Rag8 15 Nd5

15...Nd4 16 Nxf6+ Kc6 17 Nxg8 Rxg8 18 Qf6+

18...Kb5 19 a4+ Kb4 20 c3+ Kb3 21 Qxf7+ c4 22 Qf2 Qxf2+ 23 Kxf2 Nc2 24 d4 cxd3 25 Ra3+ Nxa3 26 bxa3 Kc2, and White resigned a few moves later.

(6969)

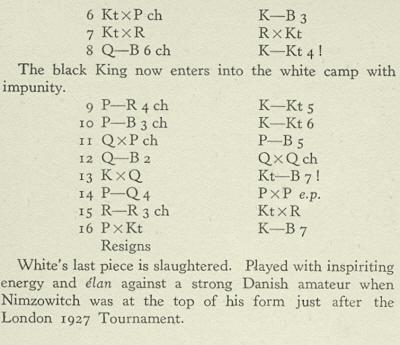

We have now obtained a copy of the column by Brian Harley (page 25 of The Observer, 25 March 1928):

(7105)

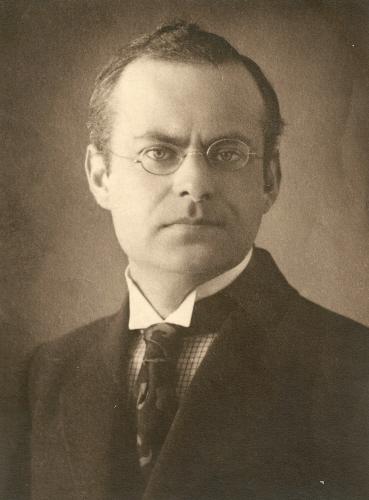

We are grateful to Per Skjoldager for permission to reproduce a photograph of Aron Nimzowitsch (circa 1916):

Mr Skjoldager informs us that he received the portrait from Mr Rolf Littorin. It appears on page 21 of the new chess catalogue of McFarland & Co. Inc., in connection with the forthcoming publication of Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen.

(7108)

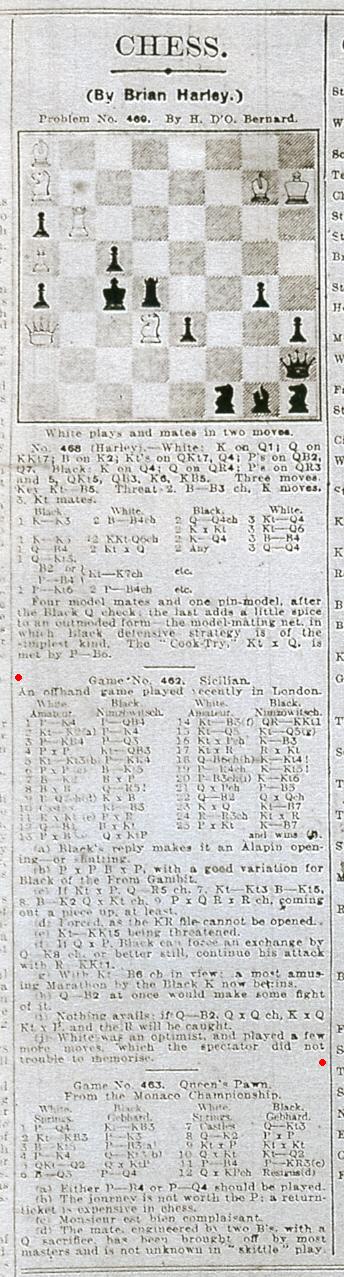

Leonard McLaren (Onehunga, New Zealand) asks about the origins of the phrase ‘building a bridge’ and wonders whether it is a misnomer.

The manoeuvre in question, in the so-called ‘Lucena Position’, was discussed in C.N. 5536. The bridge-building term (Der Brückenbau) appeared in Chapter VI of Nimzowitsch’s Mein System (Berlin, 1925). From page 117:

Concerning the ‘Lucena Position’, we also note:

Page 291 of Basic Chess Endings by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1941).

Page 42 of Championship Chess and Checkers for All by Larry Evans and Tom Wiswell (New York, 1953).

(6786)

See The Lucena Position.

Black to move. Should he castle?

Richard Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) draws attention to this position, which would have arisen in the game Spielmann v Nimzowitsch, Stockholm, 1920 if White had played Nimzowitsch’s suggestion of 17 Nf4-d3 (instead of the move actually played, 17 Be3).

Position after 16...Qg5

On page 364 of The Praxis of My System (London, 1936) Nimzowitsch gave various lines beginning 17 Nd3 Qg1+.

However, Mr Hervert points out that on page 20 of A Complete Defence for Black by Raymond Keene and Byron Jacobs (London, 1996) there is no mention of 17...Qg1+ in reply to 17 Nd3. Instead, the book states in the note to 17 Be3:

‘White’s best is 17 Nd3!, when Black should play quietly with 17...O-O-O! when his prospects are still not bad. He is ahead in development with two pawns for a piece and with White somewhat tied up.’

Except, of course, that White can somewhat untie himself with 18 Bxg5, winning the queen for nothing.

(7210)

Per Skjoldager has sent us a game which will be appearing in the book he has written with Jørn Erik Nielsen, Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 (C.N. 7108). It was a ‘serious game’ played at the Börsen Café, Riga, and the co-authors believe that it has not been published until now, except in the Riga press of the time.

Aron Nimzowitsch – Frank James Marshall1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 Nc3 d5 Involves a promising sacrifice of a pawn. Normally 5...Nxc3 6 dxc3 Be7 7 Bd3 is played, with a somewhat better game for White. 6 Qe2 Be7 7 Nxe4 dxe4 8 Qxe4 O-O 9 Bc4 Bd6 10 O-O Re8 11 Qd5 The introduction to a faulty combination. 11 Qd3 was better. 11...Be6! 12 Qxb7 Bxc4 13 Qxa8

13...Bd5! White had overlooked this move in his calculations. Now, he loses his queen but obtains quite a lot of wood in return. Bad was 13...Bxf1 14 Kxf1 Qe7 15 g3 c6 16 d3 Qd7 17 Be3 and the queen will be saved. Also 13...Bc5 was less strong than the text move since 14 d4 (not 14 Qb7 because of 14...Bb6!) 14...Bb6 15 Bg5 f6 16 Rfe1! Rxe1+ 17 Rxe1 fxg5 18 Qe4 and White has two pawns for the exchange and a good game. 14 Qxd5 Bxh2+ 15 Kxh2 Qxd5 16 d3 h6 17 Bd2 A fine move! White intends to put the black knight out of action by means of Bc3, i.e. to deprive him of the squares f6 and e5. 17...Nd7 18 Bc3 Re6 19 Rae1 Rg6 20 Re3 Nf6 The a2 pawn is not worth much since the already weak pawns on the black queen’s flank then become even more vulnerable (after Ra1). 21 Bxf6 Rxf6 22 b3 Qa5 23 a4 Qc3 24 Re2

24...Re6! 25 Rfe1 Rc6! A fine point! The rook should not be immediately placed on c6 because of 24...Rc6 25 Re8+ Kh7 26 Ne5 Rc5 27 Nd7 and perpetual check. With the rook placed at e1, Ne5 is not possible any more because of Qxe1. 26 Re8+ Kh7 27 R1e4! Qb2 28 Ne1 Rxc2 This must, if at all, happen immediately; otherwise 29 Rc4 Rxc4 30 dxc4 with a bombproof position. This attempt to split the pawns by means of the sacrifice of the exchange only fails to the vivid defence by White. 29 Nxc2 Qxc2 30 Rf4! The only move in order to avoid the loss of a pawn.

30...Qc5! A beautiful protection. 31 Re1! a5 32 Kg1 Qc3 33 Rf1 Qxb3 34 Rc4 Qxd3 35 Rxc7 Qd4 36 Rxf7 Qxa4 37 Rf3! The isolated a-pawn cannot be saved after this move. 37...Qa2 38 Re1 a4 39 Ree3 Qb2 40 Ra3 Qb4 41 Ra1! Qd4 42 Rfa3 The game could have been drawn at this point. White still made attempts to win the game by attacking the g-pawn from behind, which Black however knew how to parry with the threat of perpetual check. 42...Qe5 43 Rxa4 Drawn.

Source: page 3 of Feuilleton-Beilage der “Rigaschen Rundschau”, 10 February 1912 (new style).

Mr Skjoldager adds that Nimzowitsch’s encounter with Capablanca in Riga (game 22 in My Chess Career) was also played at the Börsen Café, Sandstrasse 11 (now Smilsu lela), as were the Cuban’s two simultaneous displays around the same time. In the photograph below, which dates from the early twentieth century, our correspondent notes that the Café is the white building on the left, behind the driver of the horse and carriage:

(7310)

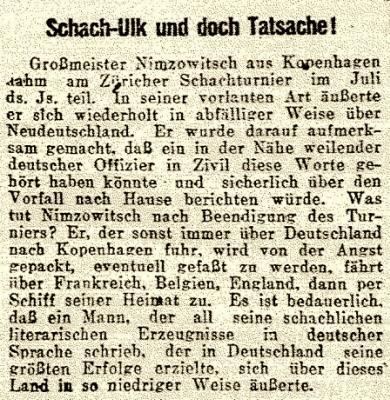

From Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) comes an item in the chess column of the Aachener Anzeiger/Politisches Tageblatt of 7 September 1934. It states that after that year’s Zurich tournament Nimzowitsch travelled home to Copenhagen via France, Belgium and England, instead of through Germany, because he feared that the German authorities might be aware of negative remarks that he had made about ‘Neudeutschland’ during the tournament:

(7644)

C.N. 1199 quoted some comments by Nigel Short on pages 40-41 of the 2/1986 New in Chess during an interview with Bert van de Kamp, in reply to the question ‘Do you have a teacher in chess, someone whose ideas have had a big influence on you?’:

‘I always liked Nimzowitsch – until recently. I got this book about Carlsbad, 1929 [IV. internationales Schachmeisterturnier Karlsbad 1929], played through all his games and they were really bad. I thought: If this is what he played like, on average, then he wasn’t a very good player. You can take any player in the world and show their best games and make them look brilliant. Nimzowitsch is not as original as people thought he was. Many of his ideas were extensions of earlier ideas of Steinitz. Actually, I’m more impressed with modern players. I’m still stunned by Fischer and more so recently. Look at his results, my goodness. He has been winning tournaments with a hundred per cent score. How is it possible? And when you play through his games they all look so easy. In 1972 he didn’t behave very well, but I liked him.’

(7749)

Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012) comes in the best traditions of McFarland hardbacks. It is supremely well researched.

(7751)

s.

Source: Carlsbad, 1923 tournament book

(8000)

Ronald Spurgeon (Sutton, England) asks about the caption to a photograph on page 1029 of Emanuel Lasker: Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by R. Forster, S. Hansen and M. Negele (Berlin, 2009). It states that in summer 1925 Lasker and Nimzowitsch played a match of ten off-hand games, Lasker winning 7-3.

We can do no better at present than reproduce the brief report in the source indicated by the book, i.e. from page 309 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 July 1925:

(8001)

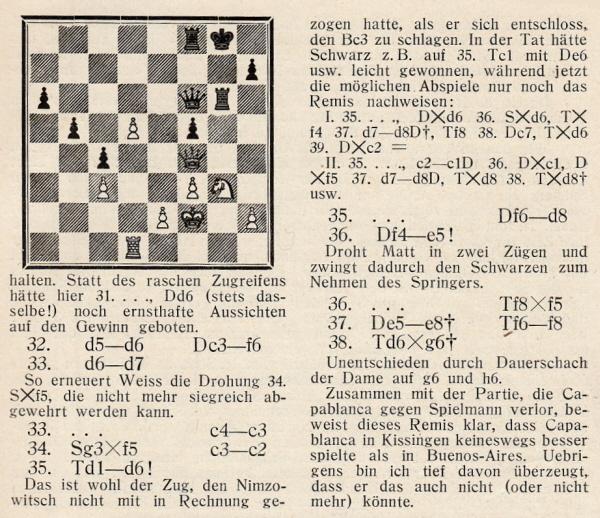

This position arose after 33 Qg3 in Nimzowitsch v Weenink, Liège, 24 August 1930. The Dutchman played 33...Qd4, and the game was agreed drawn two moves later.

It was subsequently indicated that 33...Qxf2+ would have won. From page 222 of H.G.M. Weenink by M. Euwe, M. Niemeyer, A. Rueb and B.J. van Trotsenburg (Amsterdam and Haarlem, 1932):

Part of the subsequent analysis was disputed by Albert Becker on page 32 of the Lachaga volume on Liège, 1930 (Martínez, 1976):

Nimzowitsch’s annotations in Denken und Raten – reproduced on pages 162-164 of Aaron Nimzowitsch 1928-1935 by Rudolf Reinhardt (Berlin, 2010) – shed no analytical light on the finish. Nor did he mention an alleged episode at the end of the game which brings us, not before time, to the title of the present item [‘The episode of the fainting lady’]. A woman at Liège, 1930 kept fainting and distracted Weenink into offering a draw against Nimzowitsch in a won position.

From page 147 of the September-October 1930 American Chess Bulletin:

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has located the report in Horace Ransom Bigelow’s column (‘The Chessboard’) on page 8 of the New York Evening Post, 27 September 1930. He has also found a follow-up (re-hash) item on page 8 of the newspaper’s 15 November 1930 edition:

‘The episode of the “fainting lady” at the international tournament in Liège, Belgium, recently evoked much amusement among our readers, as some of them evidently did not think that chess was also a lady’s game.

They will appreciate the higher strategy of this unknown member of the gentler sex in the game below. Aron Nimzowitsch, the tourney favorite, was in a tight place, for H. Weenink, the genial Dutch problem composer, well known to our solvers, had succeeded in securing a won position against him. Nothing daunted, Lady “X” evolved a higher stratagem: at the critical moment she fainted on Weenink’s shoulder. So flustered became he that he offered his famous opponent a draw, thereby losing a valuable half point. Who said chess was without a “lighter side”?’

Henri Gerard Marie Weenink (Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943), page 471)

(8337)

Concerning lengthy reflection at the board, is it true that after Nimzowitsch played 1 b3 against Sämisch at Carlsbad, 1929, Black thought for 40 minutes? Such a suggestion was made on page 4 of the Sunday Times, 17 November 1929:

(8537)

Another question arises from page 14 of Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess:

Where did Vidmar write those words, and was the reference really to his game against Nimzowitsch at San Sebastián, 1911 (as opposed to, perhaps, Carlsbad, 1911)?

(8580)

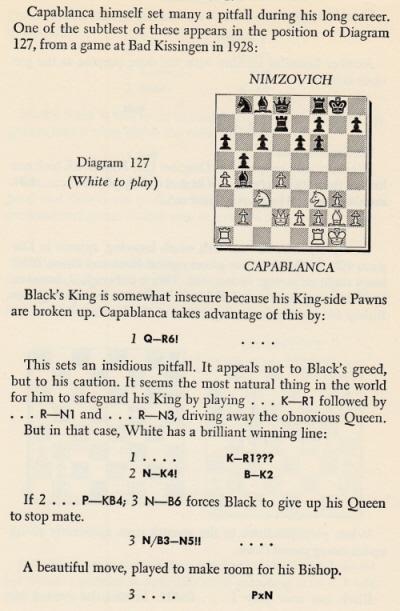

From pages 151-152 of Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1954):

In the initial diagram the white queen should be on c1. We do not know the basis for the co-authors’ statement that after the move Qh6 Nimzowitsch merely ‘took one look at the position’ before ‘quietly’ capturing the knight. Indeed, we cannot say when either player became aware of the mating line; on page 470 of the December 1928 BCM J.H. Blake wrote that it was pointed out by Alekhine.

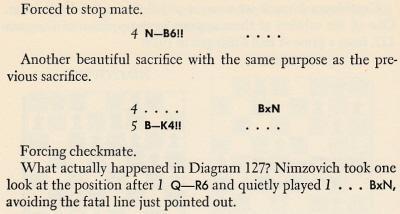

The world champion annotated the game deeply in the Basler Nachrichten, 8 September 1928:

The full notes, incorporating some further remarks, were reproduced on pages 164-167 of the October 1928 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

A different German version of Alekhine’s notes appeared, via Tidskrift för Schack, on pages 252-255 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, August 1929.

From pages 377-378 of the December 1928 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

When the Deutsche Schachzeitung had annotated the full game on pages 273-274 of its September 1928 issue, the ‘insidious pitfall’ was overlooked, the following being the note to 13...Bxc3: